Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Crucifixion

Uploaded by

David MirschCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Crucifixion

Uploaded by

David MirschCopyright:

Available Formats

CRUCIFIXION

Jesus the Nazarene, son of Joseph called Caiaphas the high priest, was crucified on Thursday, March 21, 37 CE at about 9:00 A.M. local time. He was 43 years old and a political leader of the Zealot movement, a movement that espoused the violent overthrow of the Jerusalem establishment and their Roman oppressors. He was willing to risk his life by feigning death during crucifixion in an attempt to invigorate and militarize the nationalistic sentiment then current among many Mosaeans, especially the Zealots and Essenes, with the idea that his public resurrection from death would be taken as the longed for sign from God and would become a rallying point from which the Sons of Light, with the very real help of God, would start their forty year war against the Sons of Darkness. With the specialized knowledge he had obtained from his highly placed father and their time in Egypt, and with the help of a close knit group of followers, he was prepared to risk dying on the cross for such an important cause. Countless others had sacrificed as much for their belief in Yahwehs covenant with Israel and the Law of Moses and he could do no less. As has been mentioned, the willingness to suffer the greatest of tortures and the most excruciating pain even to the point of death, in defense of their beliefs was a prominent feature of the Mosaean culture. It is difficult at this remove to fully appreciate that kind of cultural stoicism, to fully accept and appreciate that both social and theological beliefs were so firmly entrenched as to make the typical Mosaean spiritually immune to the meanest of physical degradations, that people not only were prepared to suffer and die for their beliefs, but very often were prepared to do it willingly. Jesus would have accepted torture and crucifixion as a chance to confirm his beliefs, to show God his worthiness and to accomplish his goals. The idea that he would have naturally tried to avoid pain or would have feared torture, are modern and Western in concept. Jesus was a Mosaean and a Zealot. His religion and his fierce determination to restore the United Monarchy of David made him immune to the threat of torture and pain. Scholars and traditionalists are convinced that the crucifixion of Jesus took place sometime in the early thirties, from 30 CE to 33 CE, though dates ranging from 28-34 CE have found adherents. As mentioned previously, these dates are predicated on internal evidence within the Gospels and certain assumptions about Jesus and the length of his ministry. Put simply, the Gospel stories indicate that he was born during Herod the Greats reign, that ended with Herods death in 4 BCE, that Jesus was thirty when he began his ministry and that the ministry lasted from one to three years. The great miscalculation in these traditional views is that even though most scholars agree that Jesus was most probably born between 6-4 BCE, they dont begin from that as a starting point, but calculate his thirty years of age from the point between 1 BCE and 1 CE, thus

rendering 30 CE as the date when he began his ministry thereby losing four to six years in their estimates. If, as many scholars believe, he was born in 6 BCE he would have begun his ministry in 24 CE when he was thirty, leaving a possible range (under the traditional view) for the crucifixion of between 24-27 CE. If on the other hand he was born in 4 BCE (the last date possible under Herods reign) that range changes to between 26-29 CE, still earlier than the traditionally accepted 30-33 CE range. However, the length of his ministry is only an assumption based upon the Gospel record of the number of times Jesus visited Jerusalem during his ministry. In the Synoptics there is only one visit to the city while in John the suggestion is that he has been to Passover in Jerusalem three times. This argument assumes that the Gospel stories chronicle the entirety of Jesus ministry and that that chronicle is continuous from the age of thirty. This is an easy assumption to make, but to assume that the Gospels record Jesus entire ministry is unfounded and based solely upon the imprecise and incomplete biography of Jesus contained within the Gospels. Such an assumption is hardly unassailable and needs to be re-examined. The Gospels may be the record of Jesus ministry, but because they essentially end with his crucifixion it is assumed that they represent only the last one to three years. The idea that he may have begun his ministry much earlier and that the Gospels record some of that earlier ministry seems to be uncomfortable for many scholars to embrace. If he began teaching in 24 CE at the age of thirty, there is no reason to assume that he only taught for one to three years from that year. The extensive travel required of Jesus as presented within the Gospels and the implied time required to both preach his message and develop a loyal following would seem to require more than a years time to establish and perhaps more than three years. In the First Century, before the advent of mass communications and rapid transportation, the transmission of a largely oral message was a time consuming process, making it difficult to imagine Jesus commanding the respect and fear of the population and accomplishing all he did in so short a time. Even with written material abroad in the general population, which segments of the Gospels seem to be, the dissemination of the information they contained would be time consuming both to record and to send. That Jesus traveled and taught from one end of Palestine to the other, (northsouth, east-west) and developed a loyal following while putting his message before all manner of people would seem to indicate the work of someone who has been in the political arena for some time, someone who was not just a flash in the pan but someone who had been in the public eye long enough to establish trust and be taken seriously. It is hard to imagine that anyone could be considered a prophet or wise man or messiah based upon a single teaching in a single locale. There needed to be a consistency and corroboration of his message, a groundswell of opinion necessary to elevate such an individual from the position of ordinary Mosaean to one of socio-religious power and influence and that would take some time. Consequently, the idea that Jesus ministry lasted from one to three years, while possible, is not very plausible, especially within the limitations of the traditional view. The image of the poor carpenter from Nazareth who comes from nowhere and roams Palestine preaching a message of repentance and tolerance only to find himself enough of a threat to the established order that he is tried and executed as a subversive is unrealistic

and unsatisfying. A message of repentance and tolerance on its own was hardly a threat to anyone, including the high priests and Pilate, so that without a sizable following, Jesus was hardly a threat to the established order. A poor carpenter alone is no threat no matter what he preaches. A poor carpenter with multitudes in support becomes a threat and just as was seen with John the Baptist, will be removed from the public stage if the threat is deemed great enough. It takes time to develop such a following, even for the son of a high priest as in the case with Jesus and especially when the message being preached is a political one in opposition to the established order, one that calls for revolution. Jesus was executed not necessarily because of what he taught, but because what he taught had gathered many followers thereby making him a threat. The precise date of Jesus crucifixion is important for several reasons, not the least of which is historical accuracy. Knowing the correct date helps to clarify other historical points and helps to re-date the writing of the Gospels. There are several references in both the Gospels and in Josephus that help to determine the date. For one thing, the Gospel of John indicates that Jesus was in his forties before he was crucified, rendering a date in 34 CE as the earliest possible time the execution might have taken place if Jesus was born in 6 BCE and 36 CE if he was born in 4 BCE, but there are other events that seem to confirm 37 CE. The fact that both Caiaphas and Pilate were removed from power sometime near the end of 36 or the beginning of 37 CE is very telling historically in regard to Jesus crucifixion, as is Jesus own affirmation that he would be in the ground for three days and nights and that he was crucified on Passover. These items tend to dictate that specific days of Jesus final week are definitive in determining the date of the execution. Gospel references to Passover, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, and to the Day of Preparation in the days leading up to the crucifixion go a long way to pinpointing the year in which it took place just as historical references made in Josephus help provide clues that add to the Gospels in dating the crucifixion to 37 CE. For example, in the Gospel of Mark the inclusion of certain reference points in the days before the crucifixion indicate that Passover, Nisan 15, was separated from the weekly Sabbath by a Day of Preparation. The recording of these events starts at Mark 14:12, And on the first Day of Unleavened Bread when they sacrificed the Passover lamb The first Day of Unleavened Bread is synonymous with the Day of Preparation for Passover that falls on Nisan 14 and is determined by the phases of the moon. The sighting of the new moon defining the beginning of the month of Nisan, with Nisan 14 following two weeks later and corresponding to the start of the full moon. Passover then begins on Nisan 15. Passover, as one of the high holy days of the Mosaean religious calendar, was regarded as a Sabbath day, and as such required the previous day to be a Day of Preparation, as would any Sabbath. Also, specific to Passover, extra preparation was necessary to remove any leaven from the abode due to Passover, so there were two combined Days of Preparation, one for Passover that required the removal of all leaven and one for the Sabbath that required food preparation before the Sabbath. Mark continues at 14:16 and they prepared the Passover on the same day, Nisan 14. Then, at 14:17 Mark records, And when it was evening indicating the beginning of Nisan 15 since Mosaean days began after sunset. In 14:18 it continues, and as they were reclining at table and eating clearly indicating that they were eating Passover seder

that would have been eaten at the beginning of Nisan 15, just after the sunset that ended Nisan 14. The next indication of a time change in Mark comes at 15:42, after Gethsemane, Jesus arrest and the trials before both the Sanhedrin and Pilate have taken place and Jesus had been beaten and crucified; And when evening had come since it was the Day of Preparation, that is, the day before the Sabbath, thus indicating two things; that a new day had begun, Nisan 16, and that another, different Sabbath was approaching. The mention of a second evening at this point in the story clearly indicates the beginning of a new day at sunset and that three days have been recorded, Nisan 14, 15 and 16. Mark 14:42 also clearly indicates that two Sabbaths have been mentioned because two different Days of Preparation have also been mentioned, one for Passover and one for the regular weekly Sabbath that would have begun after sunset on Friday. So the sequence of these events indicates that there was first a Day of Preparation on Nisan 14 followed by the Passover Sabbath on Nisan 15 followed then by another Day of Preparation on Nisan 16 followed by the weekly Sabbath on Nisan 17. The Gospel of Matthew follows this same chronology specifically while Luke starts out following it and then becomes somewhat vague, omitting some of the later time markers that help to establish the sequence while correctly compressing much of the action into a single day, Nisan 15. The Gospel of John, because of its frequent and lengthy theological inclusions is the most vague of the four, making it difficult to determine the same timeline of events as the Synoptics. Mark, being the earliest rendition, is also the clearest and easiest to decipher, laying out a neat timeline of these events. Given a suggested ten year time span during which the crucifixion reasonably could have taken place between 27-37 CE, only three years present the same weekly chronology where a Day of Preparation falls directly between two Sabbaths; 27, 30 and 37 CE. As has been noted, since Jesus was in his forties near the end of his ministry, the years 27 and 30 CE must be excluded from consideration because Jesus would have been too young, leaving only 37 CE as a calendar match for the sequence of events described in the Gospel of Mark. Whether or not Joseph and Jesus consciously chose the year 37 CE to initiate their plan or whether it was thrust upon them by circumstance is difficult to determine. Certainly, the death of John the Baptist and the failure of the Samaritan uprising on Mount Gerizim late in 36 CE must have contributed to their expediting the institution of the plan just as the unexpected arrival of Lucius Vitellius, the Roman legate for Syria, in Jerusalem during the Passover of 37 CE must have caused them to suddenly alter certain of the details. Either way, as it turned out the sequence of the Passover Sabbath-Day of Preparation-weekly Sabbath worked surprisingly well for what they needed to accomplish. Having Jesus die on the Passover Sabbath had always been an important part of their plan, allowing him to assume the role of the Paschal lamb, the spiritual sacrifice for the Mosaean people, and with Joseph as High Priest, manipulating Jesus arrest and trial on charges of blasphemy at the exact right moment was no problem. The initial charge of blasphemy was extremely important to the outcome of the plan since it allowed the Sanhedrin to meet late at night on a Sabbath, by justifying their assembly as a sacred assembly. According to Leviticus 23:1-3, doing Gods work on a holy day rather than dealing with more secular affairs would have been viewed as in violation of the Sabbath prohibition against all forms of work.

Joseph Caiaphas was aware of this loophole and planned accordingly. The initial charge of blasphemy that he leveled against his son was enough to gather the members of the council, but it was not enough to convict Jesus and Joseph knew this. The evidence that Jesus was called (or called himself) the son of God was specious at best. Other contemporary miracle workers and messianic claimants such as Honi the Circle Drawer and others had carried the same title without direct retribution or charges of blasphemy being made against them. The designation that one was the son of God was only an appellation meant to convey that persons extreme righteousness and piety. It was not, on its own, automatically a demonstration of blasphemy. Knowing this, Joseph felt safe in laying the charge against Jesus, certain that his son had committed no crimes that would put him in jeopardy of being tried and convicted of breaking any Mosaean law that might lead to his execution. That is why within the Gospels the Sanhedrin found it difficult to convict Jesus even though they had produced false witnesses against him, and while Caiaphas made a great show of his anguish and despair at Jesus actions he knew that his son would not be convicted of Mosaean crimes. Doing all this on the high holy day of the Passover Sabbath insured that the streets would be relatively empty and that there would be far less chance of public interference in the arrest and trial. Most Mosaeans would have stayed indoors during this important Sabbath, not wishing to risk the charge of breaking the Sabbath rules by venturing outside. The punishment for even the hint of doing work on such an occasion was death according to Mosaean law. No work could be done, nothing carried, no food prepared, not even a candle could be lit. Even though the Passover Festival lasted for a week, only the Sabbaths prohibited any form of work, so that while the crowds of pilgrims in Jerusalem that the priests feared might have been a threat to riot over the arrest and trial of a well- known preacher and prophet, there was almost no likelihood of such riots on the Sabbaths. Those people that the Gospels indicate were about, the people gathered in the courtyard of the high priests house and those in the streets as Pilate presented Jesus to them, seem to be smaller groups that were assembled with specific agendas to fulfill; in the first case to provide witnesses against Jesus and in the second to call for his death. Both of those agendas are clearly driven by the desires of the high priests in an attempt to rid themselves of Jesus, but there is no hue and cry throughout the city that Jesus had been arrested and was on trial. For Joseph, it was an important benefit to enacting the plan on such a day. Another misconception that tradition routinely reinforces is the extent of physical abuse Jesus actually suffered prior to and during the crucifixion. The extra biblical accounts of his suffering are Christian propaganda at its worst and continue today through Christian apologetics and Christian entertainment such as Mel Gibsons The Passion of the Christ. It seems to be necessary for Christians to both invent and believe the worst possible physical tortures for their hero in order to effectively embellish his legend, much as Hollywood metes out the most extreme punishments on its heroes in order to increase their heroic status. The more suffering the hero undergoes, the greater his prestige and worshipping by adoring followers. In Jesus case, since he was identified as the suffering servant, the physical abuse demanded of him by his later followers was extreme. It was imperative for this man who took on the sins of the world, to suffer the greatest physical

pain and degradation before his demise because after all, the value of a mans life and especially his teachings is often measured by the difficulties and suffering he has faced and had to overcome. Unfortunately, the Gospel record tells practically nothing about the tortures that Jesus may have suffered. The idea that he endured extreme physical abuse is nowhere in the Gospels and only shows up much later through Christian apologetics. Tradition has created the wildest and most shocking accounts of his torture at the hands of the Romans in details almost too graphic to relate, so much so that one might be excused for believing that those gruesome details were in fact from a first hand eyewitness account. Details as graphic as the ripping away of his flesh to the exposure of his veins, ribs and organs, the specifics of the implements of torture used down to the bits of sharp animal bones at the ends of the flagellum, the sadistic glee with which his torturers approached their task, are all recorded in modern exegesis, literature and film. Christian apologetics have so fictionalized the hours and moments leading to Jesus crucifixion that it is difficult to rationally and reasonably determine what might have happened. The historical record has been so completely corrupted by these ghoulish retellings that anyone desirous of the truth might despair. Fortunately such is not the case. The unembellished accounts are still there in the Gospels, free of the horrific details. The accounts now current in our society are nothing more than fictional accounts created by Christian believers, in order to make Jesus more heroic, more legendary. Sadly, as with most of the other distortions that tradition has introduced into the Gospel stories, these accounts of ghastly torture have become so firmly imbedded in the story that they are nearly impossible to dislodge. Christian believers are so intent on the truth of these accounts that they willfully disregard their own Gospels in order to preserve the fictional suffering endured by their hero. The Gospel accounts, however, are so simple, so bereft of any fictional embellishments and horrific detail that it is not surprising that their matter of fact recounting has been reworked into the tradition that exists today. To fully grasp the hyperbole that tradition has attached to the events leading to the crucifixion it is important to recount the actual Gospel verses. Mark 15:15; So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released for them Barabbas and having scourged Jesus, he delivered him to be crucified. Luke 23:16&22, I will therefore punish and release him. (There is no scourging mentioned in the Gospel of Luke for Jesus before the crucifixion, only punishment). Matthew 27:26; Then he released for them Barabbas and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified. John 19:1; Then Pilate took Jesus and flogged him.

Those are the pertinent passages that cover the worst of the torture that Jesus was subjected to, and while they do not mention the other physical abuse he endured, the slapping, hitting and spitting by the Roman soldiers, they do address what would have been the most extreme segment of the torture he would have faced, namely, the scourging or flogging. From these three meager accounts has developed all of the highly detailed and graphic renditions that are now part of the legendary tradition associated with this event. It seems difficult to accept that all of the contemporary accounts with their lurid details could have emanated from such spare beginnings, yet such is the case. That Jesus may have been tortured nearly to death in exactly the manner proposed by Christian apologists is certainly possible, but the Gospel record seems to indicate otherwise. In light of that alternative it seems irresponsible to fictionalize the elements of his torture, especially to the extremes currently in use. Part of the problem in establishing and defining what exactly Jesus suffered under torture is contextual in nature. Since there is no eyewitness recounting of the event, it is necessary to interpolate from other sources the nature and technique of Roman scourging and then apply it to Jesus. The problem with that is that it is merely supposition, an educated guess as to what he may have endured. Clearly, the Roman punishment of scourging was a horrific and often deadly form of torture and may have included many of the graphic results fictionalized by Christian apologists, but that does not necessarily mean that he suffered the same fate. There are implications within the Gospels that would seem to indicate otherwise, predominant among them the fact that the man in charge of Jesus torture and execution seemed less than inclined to convict Jesus of any crime warranting an excessively violent response. Pontius Pilate, throughout the various Gospel accounts, consistently avers Jesus innocence and the lack of evidence for convicting him of any crime requiring the death penalty. It is made quite clear in the various accounts that Pilate found no guilt in Jesus and would have been content to punish and release him (Mk. 15:14; Lk. 23:4, 23:14-16; Mt. 27:23; Jn. 19:4, 19:6). Biblical exegetes often point to this response as nothing more than a politically correct reaction by the Gospel writers to avoid blaming the Romans (who were still in power in Palestine) for anything to do with Jesus death, while laying the blame pointedly at the feet of the Jews. While such a politically correct intention by the writers may have been foremost in their minds as they recorded the events surrounding Pilate and Jesus, that does not automatically guarantee that such reasoning was the only discernable motivation current at the time. There were reasons why Pilate might have behaved as he did towards Jesus, not the least of which was a pronounced change at the highest levels of Roman foreign affairs, that would have encouraged Pilate to act with caution and even solicitude towards a Mosaean prophet and preacher who appeared to be popular with a large part of the population. Beginning in 31 CE there was a dramatic change in leadership in Rome that was felt throughout the Roman Empire. In 31 CE, Lucius Aelius Sejanus, the veritable co-ruler of the Empire along with the legitimate Caesar, Tiberius, was arrested, tried and executed by the Senate on the order of Tiberius. Sejanus, who had had a profound impact on the policies and affairs of Rome for many years while Tiberius was safely ensconced in semi

seclusion on the Isle of Capri, was brutal, harsh and unforgiving, especially in matters of foreign affairs. There is some suggestion in Philos Legatio verse 160 that Sejanus held pronounced anti-Semitic views that clearly influenced his decision making; for he [Tiberius] knew immediately after his [Sejanus] death that the accusations which had been brought against the Jews who were dwelling in Rome were false calumnies, inventions of Sejanus, who was desirous to destroy our [Philo of Alexandria was Mosaean] nation Sejanus not only tried to create difficulties for the Jews living in Rome to the point of their possible extermination, but was also intent upon the destruction of the entire Mosaean nation both domestic and foreign. As Eusebius remarked in his Ecclesiastical History, Sejanus made great exertions in Rome to destroy the whole nation and that in Judaea Pilate caused great commotion among the Judeans because he desired to undertake something with respect to the Temple, that was contrary to their institutions (the introduction of the Roman standards or the building an aqueduct with Temple funds). Pilate, either through a shared anti-Semitism with Sejanus or under Sejanus direction, carried out a policy of anti-Semitism towards the Judaeans and perhaps towards Mosaeans at large, at least during the early years of his tenure. It should not be surprising that such was the case since the implication is that Sejanus directly or indirectly caused Pilate to be appointed prefect of Judaea. Both men came to their respective positions of authority at about the same time. Sejanus, who had been prefect of the Praetorian Guard from 14 CE, became the de facto ruler of the Empire when Tiberius withdrew to Capri in 26 CE while Pilate was appointed to prefect of Judaea that same year. How well the two men knew each other and shared their ideas is not part of the historical record but the coincidence of their shared anti-Semitism and the apparent connection between them that of leader and subordinate cannot be ignored. Surely as co-princeps of the Empire, Sejanus would have been well aware of Pilate and his activities in Judaea and, at least in the years before 31 CE, could have removed him from power had he felt the need or felt that Pilate was acting in any manner detrimental to the welfare of the Empire. That Pilate remained in power from 26 to 31 CE indicates that Sejanus must have approved in large part of his Judaean policies and may, in fact, have sent him there as a provocateur in an attempt to provoke the Judaeans into open rebellion, a rebellion that Rome was sure to crush, thereby securing the means to destroying the Mosaean nation without having to justify it to Tiberius and without having to cast the first stone. What is pertinent to fully understanding the crucifixion is that once Sejanus was executed in 31 CE Tiberius became fully aware of his anti-Semitism and the policies that reflected it. As a result, in late 31 or early 32 CE, Tiberius ordered a decree to be sent out across the Empire refuting Sejanus anti-Semitism. Again, Philo records in his Legatio (verse 161); And he [Tiberius] sent commands to all the governors of the provinces in every country to comfort those of our [Mosaean] nation in their respective citiesAnd he ordered them to change none of the existing customs Essentially, Tiberius ordered a hands off policy regarding the Mosaeans to all of his prefects and procurators across the Empire. Such a decree would have pointedly included Judaea and Pilate and it is this change in policy, from Sejanus anti-Semitism to Tiberius tolerance that is reflected in the Gospels portrayal of Pilate, thus refuting the later interpretation that Pilates

seemingly contradictory change in personality was the politically correct means used by the Gospel writers to endear Jesus to a predominantly Roman audience. The historical truth of Tiberius decree also refutes any date earlier than 32 CE for the crucifixion. The change in Pilates character that is witnessed in the Gospels is based upon historical events, thus eliminating a crucifixion in any year prior to the decree that caused that change. Tiberius decree of 31 CE in essence confirms the Gospel story of Pilate and his previously misunderstood change in character and how he dealt with Jesus and the Mosaeans. The two contradictory Gospel views of Pilate now become historically viable; that he began his tenure as prefect of Judaea under Sejanus as an anti-Semitic, confrontational governor intent upon subjugating the Mosaean populace and ended, a few years later, as a governor held in check by Tiberius decree, conciliatory and tolerant, unwilling to pronounce a death sentence upon a popular preacher and prophet in the absence of any evidence. Consequently, the traditional Christian apologist view that Pilate had Jesus scourged nearly to death is no longer tenable. Pilate clearly was looking for a way out of the situation the Judaean leaders had presented to him. He was intent on following the spirit of Tiberius decree, and without some form of evidence that clearly indicated that Jesus was guilty of a capital crime was reluctant to persecute and execute him. In fact, had not the Judaean leaders threatened Pilate with being no friend of Caesars, there is every likelihood that Jesus would have been punished and set free. Pilate, as a Sejanus appointee, would have been on extremely thin ice as far as Tiberius was concerned (Tiberius executed dozens of Sejanus family, friends and appointees) and could have ill afforded any word reaching Tiberius that he was anything less than completely loyal. Caught between obeying the decree to prove his loyalty on the one hand and the potential accusation that he was no friend of Caesars on the other, Pilate opted for the execution of Jesus to confirm his loyalty to Tiberius. The death of one preacher, even if he was preaching sedition, might not catch Tiberius eye, whereas a delegation of Judaean leaders making wild accusations certainly would. With this in mind, it is difficult to presume that Pilate would have meted out the harshest punishment upon Jesus. Certainly Jesus was nothing to him but a politically awkward affair that seemed to be generated by the high priests and their immediate followers. As will be seen later, at that time just before the crucifixion Pilate was unaware of who Jesus really was and did not make the connection that the man standing before him, accused by the Jerusalem elite of blasphemy and sedition, was in fact the same man who had incited the Samaritans to climb Mount Gerizim some months before, the Samaritan Taheb, who had escaped capture when Pilate had sent troops to intervene (which is not too surprising, since modern scholars still fail to make the same connection, that Jesus and the Samaritan Taheb were one and the same). To Pilate, Jesus may have seemed a nuisance or a mild threat to the civic peace, especially at Passover, but not much more. The high priests were much more agitated about Jesus and his activities (they would have known of the connection with Mount Gerizim) but could only make vague accusations against him for fear of alerting the Romans to the reality that there was an active rebel movement extant in Judaea and elsewhere throughout Palestine. The Herodian faction of the high priesthood could not afford to have the Romans too well

informed about the seditious activities taking place within their jurisdiction, the repercussions would have been too severe. Added to this was the Zealot faction, lead by Jesus father, who were intent on having Jesus crucified so that he could resurrect from the dead and thereby claim divine intervention as a means of garnering political clout. So it is unlikely, in contradiction to tradition, that Pilate would have had Jesus severely beaten. It is more likely that in keeping with Tiberius decree he preserved Mosaean customs regarding such an event and had Jesus flogged the customary thirty-nine strokes (Deuteronomy 25: 1-3. Any number of stripes, up to a maximum of forty, could be meted out to a malefactor depending upon his crime, but in actuality, thirty-nine was the maximum number delivered so as to avoid any chance of mistakenly going beyond the mandated forty. Such an error was a crime in itself and required that the overseer who was delivering the punishment might be then guilty of involuntary manslaughter and could be exiled to a city of refuge) that were indicated in Mosaean law, even though he ultimately planned to execute him. By doing so, he maintained the letter of the Mosaean law, thereby satisfying Tiberius decree while still satisfying the high priests who were no doubt clamoring for a malqut (flogging) as well as a karet (excision from society) by way of crucifixion. The question then becomes, could Jesus have survived both the scourging and the crucifixion given this new scenario? With Pilate disinclined to levy the harshest beating upon him, could Jesus have managed to survive thirty-nine lashes and been strong enough afterwards to live through six hours of crucifixion? There is corroborating evidence from many sources that indicates that he very well could have survived such an ordeal. Although the severity of the scourging suffered by Jesus is not attested to anywhere in the Gospels, Christian apologists insist upon sensationalizing the event to such an extent that they might easily be accused of dishonesty at best and or a certain sado-masochistic leaning at worst. The graphic details imagined by such authors, in the absence of any eyewitness accounts are ludicrous in their excess and useless as any historical corroboration that they purport to be. The only reason that such accounts continue to be written by educated men who should know better is that tradition has so distorted Jesus suffering (both during the scourging and the crucifixion), that it is now accepted that it was so extreme as to go beyond what any mortal man could endure. The idea seems to be that the greater the suffering, the greater the hero. In fact though, the Gospel accounts are straightforward and devoid of any embellishments when recounting the scourging of Jesus. As has been mentioned above, the relevant passages of Mark 15:15, Luke 23:16&22, Matthew 27:26 and John 19:1, about the scourging are brief and nondescript. They are devoid of any details, violent or otherwise. From these four scant accounts tradition has embellished in graphic detail all the subsequent renderings of Jesus scourging at the hands of the Romans to the point where fiction has replaced the actual Gospel accounts. Today, Christians, Christian apologists, biblical scholars and historians assume that the flogging of Jesus was a bloody, horrific mess that left him near death but the Gospels make very little out of Jesus scourging (Luke mentions only punishment). While it may be assumed that early readers would have been well aware of scourgings and what they entailed, those same readers also

would have been equally aware of the difference between a Roman scourging and a Mosaean scourging. Though Christian Apologetics is filled with such hyperbole and one could reasonably turn to almost any Christian work to find the completely imaginary obscene details of Jesus torture and death, it will suffice to record only one example here. The following is taken from an article written for the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) by several medical doctors. The article, Study on the Physical Death of Jesus Christ, by William D. Edwards, MD, Wesley J. Gabel, MD iv. And Floyd E. Hosmer, MS, AMI, is extreme in its gory suppositions, so that only a brief quote need suffice: Then, as the flogging continued, the lacerations would tear into the underlying skeletal muscles and produce quivering ribbons of bleeding flesh. The place for such purple prose would seem better suited to works of fiction than to articles of biblical scholarship. Without eyewitness testimony, such imaginative renderings of Jesus suffering serve only to obscure what actually might have happened, allowing tradition to again divert scrutiny from other possible explanations. The fact is, that if the Romans adhered closely to Tiberius decree in regards to the punishment of Jesus, there is every likelihood that he only received the customary thirty-nine stripes, and that those may have been delivered not by a Roman flagrum but by a Mosaean whip or lash, as was the custom (the flagrum would have been reserved for the punishment of non-Mosaean criminals). According to The Encyclopedia of Medicine in the Bible and the Talmud by Fred Rosner (Book-mart Press Inc., North Bergen, New Jersey, 2000), such a whip or lash would be made of calf hide (Makkot 23a). The lash is short so that it not reach the heart when being applied to the back (ibid.). A flogging in progress is stopped if the culprit urinates or deficates because of the humiliation (Makkot 23a). In addition to the Mosaean concern for humiliation of the culprit and for the possible lethal outcome of exceeding the forty stripes, the judges responsible for witnessing the punishment could at any time stop the flogging if they thought that to continue would endanger the culprits life (JewishEncyclopedia.com, article on Stripes). The Mosaean idea of a flogging was, apparently, to administer a punishment commensurate to the crime, not to flog the criminal nearly to death. This is confirmed in the case of Paul who suffered at least five separate floggings (2 Corinthians 11:24-25) as well as several beatings and survived them all. The Romans, reduced to mimicking Mosaean custom in accordance with Tiberius decree, and the Judeans, restricted by Mosaean law, were in fact limited in the amount of corporal punishment they could actually mete out to Jesus before the crucifixion. Tradition and legend notwithstanding, Jesus could well have survived the ordeal stoically without aid but anesthetized as he was (as will be shown later), probably felt little or no pain throughout the experience. Also, the massive blood loss suggested by many Christian apologists and biblical investigators that is often cited as contributory to his death is a thing of fiction and fervid imagination; no such blood loss occurred. Without the severe beating and blood loss attested to by later, non-eyewitness recreations, Jesus ability to physically withstand the rigors of crucifixion was greatly enhanced. Again, unlike other forms of capital punishment such as decapitation, stoning or drowning,

which could not be manipulated or faked, crucifixion under the right circumstances could be manipulated and therefore allowed for a reasonable chance for survival. Many will argue that the crucifixion, with its severe physical stresses and abuses, was enough, in and of itself, to cause Jesus death, but here again tradition, a lack of first hand knowledge and a desire by apologists to embellish and overstate Jesus suffering have so distorted the event as to render their versions highly suspect. In the last few years greater scrutiny has been directed to the particulars of crucifixion in general and Jesus in particular by investigators such as Dr. Frederick T. Zugibe, MD, PhD. and others, with a more scientific, less emotional approach to the suffering and cause of death of those crucified. Still, as with flogging, the blood lust continues in these accounts dependent as they are on the traditional view of the pre-crucifixion suffering Jesus supposedly endured. With the new realization that Jesus suffered only the customary 39 stripes delivered not by the Roman flagrum but rather by the Mosaean lash, a re-evaluation of his crucifixion and the potential cause of death must to be made. The traditional view of Jesus crucifixion (and by extension to most First Century crucifixions) is one of a tortured individual suspended from a high wooden cross with nails through either the wrists or the palms of the hands and also the ankles. In some accounts, research has provided a sedum or seat for the victim to rest upon and in some accounts the victim is tied rather than nailed to the cross. Death occurs (especially in the case of Jesus according to Dr. Zugibe) from hypovolemic (loss of blood volume) and traumatic shock, and not by asphyxiation as earlier interpretations had suggested. Often times, the specific crime for which the victim was being executed was posted on a sign at the top of the cross as a warning to other potential malefactors, and in general, crucifixions were performed in or near high traffic areas along roads or near town gates to be visible to the greatest number of people. As a form of punishment they were designed and intended as a profound message of deterrence. As has been stated, there were other, easier means available for capital punishment for both the Mosaeans and certainly for the Romans who saw death not only as a reasonable punishment, but also a form of entertainment. For the Romans, it was an effort to crucify someone, especially large numbers of victims and there was very little entertainment value involved (unlike the games held around the empire where prisoners and captives were often devoured by wild animals for the entertainment of the citizenry). Therefore, it was important that the crucified victim stay alive as long as possible. A corpse hanging on a cross is certainly a deterrent, but a living, suffering victim that can vocalize their suffering and hangs on a cross day after day while people pass them by repeatedly on their way about their lives has a much greater impact. Consequently, rather than being the high, somewhat remote structures of tradition, crosses were probably short structures that kept the victim at nearly eye level to passersby. This served several purposes, the first being that shorter crosses required less wood. In a land where construction grade lumber was at a premium, the idea of using long lengths of timber posts to hoist crucified victims high into the air would have been seen as a waste. Secondly, the deterrent impact of crucifixion was designed to be intimate and close, not remote and impersonal. Lower crosses saved wood and also brought the

intended message home directly and intimately. People walking by the site of executions could easily look into the eyes of the victim, could hear their labored breathing, could listen to them cry for mercy and water, could empathize with those crucified with an immediacy and visceral connection that would have been less intense with someone crucified high above them to a taller cross. Thirdly, shorter crosses were easier to erect and utilize. The taller crosses traditionally rendered in Jesus crucifixion would have required three or more soldiers to set up; one man on each end of the cross piece to hoist up the victim using stout poles and one man, perhaps on a ladder, to guide the cross piece to the top of the upright and affix the titulus. The Roman army was successful largely due to its efficiency both in combat and in its day-to-day routines. Manpower was well utilized and wasted effort was frowned upon. With the shorter cross that was probably used, the execution could have been performed by just two men, attaching the victim to the cross piece and then lifting both the man and cross piece above their heads and into place at the top of the beam, that was probably a semi-permanent fixture partially buried in the ground. Some confirmation for the use of shorter crosses comes by way of ancient sources that depict crucified victims being partially devoured by scavengers, including birds and wild dogs. While birds certainly would not have any difficulty pecking away at the head and upper torso of such a victim, the idea that dogs and perhaps jackals would be able to feast upon the body of someone hanging from a tall cross seems problematic, though not entirely impossible. Such suggested carrion eating seems more plausible if the victim was much closer to the ground, with their feet hanging perhaps only inches off the ground. Then, too, once the corpse had served it purpose as a message and once the carrion eaters had had their fill, the removal of the body to prepare for the next victim would have been much easier, again requiring perhaps only two soldiers to lower it down. It cannot be stressed too strongly that the idea of a tall cross, with it requirements of greater manpower, was an impractical solution to the workload problem of crucifixion, especially when mass crucifixions of hundreds, even thousands of victims were performed, as was the case periodically in the First Century. Another problem associated with our understanding of the specifics of crucifixion was the method used to attach the victim to the cross. While it is generally accepted that Jesus and others were nailed to their crosses, either through the wrists or palms and the ankles, forensic studies and ancient evidence seems to dispute the idea that victims were attached to the cross solely by nailing. Unfortunately, the forensic recreations developed by Dr. Zugibe and others do not allow a fully accurate model of an actual crucifixion. In the case of Dr. Zugibe, his test subjects were affixed to the cross by an artificial means (heavy leather gloves and tabs for the hands and a seatbelt strap for the feet) thus preventing an accurate rendering of the crucifixion. The same is true of the Philippine martyrs crucifixions where the participants stand upon a small platform attached to the cross that carries their weight. There is really no way to accurately determine the real physical affect of crucifixion on the human body short of performing an actual crucifixion. In the first half of the Twentieth Century, Pierre Barbet, a French MD and surgeon came very close to an actual crucifixion when he took a corpse and had it nailed to a cross. What he found indicated that unless great care was given to the placement of the nails, the weight

of the body tore the hands over the nails. As Dr. Zugibe noted in his work, Pierre Barbet Revisited (Sindon N.S., Quad. No.8, December 1995);

When Barbet passed nails through the middle of the palms of freshly amputated hands and found that they tore through the skin between the fingers at a pull of about 88 pounds, he collated this with mathematical calculations which reveal that if a body is suspended with the arms at an angle of about 68 degrees with the upright (stipe) there is a pull on each hand greater than the entire weight of the body.

While there are areas of the hand and wrist that are technically strong enough to support the weight of a crucified body, the idea that a single nail through each hand or wrist of a victim would be enough to secure them is untenable. A severely suffering individual hung on a cross is apt to writhe and squirm in reaction to the pain and as a result are inclined to try to wrest their hands free from the pain inflicting nails. Regardless of what an acquiescent body might accomplish as far as pulling the nails through the hands by dead weight, a conscious or semi-conscious individual would attempt to free their hands with as much effort as they could muster. This is why traces of olive wood were found between the head of the nail and the anklebone of the First Century crucified victim. The Romans used wooden plaques to prevent the victims from pulling their hands and feet over the nail heads. That an individual might be capable of enduring the extreme pain of consciously pulling their hand over the nail head, one need only remember that in April of 2003, Aron Ralston, while hiking in Blue John Canyon in Utah got his arm trapped beneath an eight hundred pound boulder and could not move. After five days, starved and dehydrated, Ralston took a knife and cut off his trapped arm. It is a clear example that when in extremis, humans are capable of nearly unthinkable acts not only to survive, but to relieve themselves from extreme pain as well. The olive wood plaques would help to prevent someone from pulling their hands away from the nails in one direction, but they could not stop the person from attempting to pull their hands from between the plaques and the patibulum or horizontal cross piece of the cross. Some other method must have been used to prevent the victim from tearing their hands in two as they worked them against the nails and slid them from between the plaques and the patibulum. The easiest solution (and one that the Romans no doubt used) was to tie the arms of the victim tightly to the patibulum. Tying the arms, proximally to the elbow joints, kept the individual from pulling in any way against the nails. With the arms tied in such a fashion the muscles of the shoulder and upper arm were incapable of a enough great force to the lower arm and hand to pull the hand from the nail by pulling the nail head through the hand. Sliding the hand from between the plaque and the patibulum would be restricted because the elbow joint was held against the tight bonds and kept the arm from moving laterally. Tying a victim to a cross in such a way also helped in supporting the majority of the bodys weight, and allowed the nails in the hands to be

placed almost anywhere since they were no longer necessary for carrying any weight. The nails were used only as a means of pinning the hands to the patibulum so that the arms could not be wriggled loose from the ties. Both means of attachment were mutually supportive, the nails helped secure the ties and the ties helped secure the nails. As long as the executioner did not sever either the radial or ulnar arteries while placing the nails, thereby causing the victim to bleed to death, the nails could be placed anywhere in the palm or wrist region, and with the weight of the body carried by the ties rather than the nails the actual physical damage to the hands or wrists would have been minimized, as is seen with the Philippine crucifixions. Consequently, Jesus wounds from the actual crucifixion, while horrible, would not have been life threatening and might not have even incapacitated him. After Aron Ralston amputated his arm (with the physical and emotional trauma that would have resulted), he was able to rappel 65 feet to the canyon floor and to hike seven miles to the trailhead. Ralstons story is not the only example of the human spirit and body overcoming severe trauma in an attempt to survive and so it should not be assumed that the scourging and crucifixion endured by Jesus necessarily placed him at deaths door. It is only Christian tradition that indicates his physical state was so degraded and abused as to be near death. In actuality he had suffered a beating of indeterminate strength and duration, a thirty-nine stroke lashing and the four puncture wounds of the crucifixion. Painful and bloody as these wounds might have been, they were not life threatening. The crown of thorns and the piercing of his side by the soldiers lance would have added to his suffering and blood loss, but not significantly. The crown of thorns might have produced many small superficial wounds and the lance laceration could have been superficial as well, since it was not intended to be a coup de grace but merely a brief sharp pain to determine death. Even Pilate, who must have had great familiarity with crucifixions and their outcomes, when informed of Jesus demise, was surprised by the rapidity with which his death had occurred. Could Jesus then have survived the torture and crucifixion recorded in the Gospel stories? The Gospels and other historical documents like Tiberius decree of 31-32 CE when examined carefully, indicate that such could have been the case. With his profoundly righteous and fanatical Mosaean beliefs, the concept of torture and suffering held nothing frightening for him, and in fact afforded him with another opportunity to prove to God his worthiness and his steadfastness to Mosaean law. Since he did not hang upon the cross long enough to succumb to exposure or dehydration, the wounds inflicted by the crucifixion were not most likely severe enough to kill him, and even though some Christian apologists like to imagine that the lance point thrust into his side was deep enough to penetrate to the pericardium and thereby explain the blood and water that flowed forth from the wound, the reality was that the lance barely broke the skin enough to allow watery blood to flow out and certainly was not meant to replace the breaking of the legs that was prescribed in such instances to hurry death along. Roman soldiers could hardly be expected to break the legs of two other crucified criminals while stabbing to death a third. The spear that was thrust into Jesus side was not meant to kill him, but to verify consciousness. Had the spear point roused him, there is no doubt the soldiers then would have broken his legs.

If Jesus could have survived the rigors of this flogging and a crucifixion, why then did he appear to succumb to these physical tortures? Why did he call out, I thirst and then receive the taste of gall soaked in a sponge handed to him at the end of a reed, only to succumb brief moments later? What motivated him to risk his life and well being by feigning death on the cross? The following sections will examine first what drove him to attempt such trickery, and later how he was able to accomplish it. There are very clear reasons why he needed to feign his death and resurrection and those reasons had nothing to do with establishing his divine nature. Jesus knew that in order for the Kingdom of Heaven to be established on earth, there must first be a sign from God. His resurrection would provide that sign.

You might also like

- “All Things to All Men”: (The Apostle Paul: 1 Corinthians 9: 19 – 23)From Everand“All Things to All Men”: (The Apostle Paul: 1 Corinthians 9: 19 – 23)No ratings yet

- Your Convictions About The Resurrection of Jesus ChristDocument2 pagesYour Convictions About The Resurrection of Jesus ChristyuotNo ratings yet

- Bishops Homily - Palm SundayDocument25 pagesBishops Homily - Palm SundayMinnie AgdeppaNo ratings yet

- Jesus Christ Founded The One Holy Catholic and Apostolic ChurchDocument18 pagesJesus Christ Founded The One Holy Catholic and Apostolic ChurchPhil FriedlNo ratings yet

- Good Friday ReflectionDocument2 pagesGood Friday ReflectionJose MagcalasNo ratings yet

- Thesis 1: GALLETIS, Razil S. (46 Gen) REVELATION AND FAITH (Dr. Victoria Parco, AY 2013-2014)Document21 pagesThesis 1: GALLETIS, Razil S. (46 Gen) REVELATION AND FAITH (Dr. Victoria Parco, AY 2013-2014)Crisanta MartinezNo ratings yet

- Palm SundayDocument77 pagesPalm SundayRaffy RoncalesNo ratings yet

- The Harvest Is Plentiful, The Laborers FewDocument4 pagesThe Harvest Is Plentiful, The Laborers FewGrace Church ModestoNo ratings yet

- Exegesis Exodus 2,11-22Document6 pagesExegesis Exodus 2,11-22deasiscrisNo ratings yet

- What's So Good About Good FridayDocument4 pagesWhat's So Good About Good FridayP Samuel Prem AnandNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document45 pagesChapter 1rickydepths100% (2)

- Etymology: Textual HistoryDocument5 pagesEtymology: Textual HistoryLeo CerenoNo ratings yet

- Word Study On BaraDocument5 pagesWord Study On BaraspeliopoulosNo ratings yet

- Eucharist Thesis StatementsDocument5 pagesEucharist Thesis StatementsBonirie Tabada RosiosNo ratings yet

- 1994 Issue 2 - Biblical Charity: Ministering To The Poor Through The Church - Counsel of ChalcedonDocument5 pages1994 Issue 2 - Biblical Charity: Ministering To The Poor Through The Church - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNo ratings yet

- Palm Sunday 2020Document6 pagesPalm Sunday 2020Jackson Hearn100% (2)

- Throne of GraceDocument4 pagesThrone of GraceGiovanni Christian LadinesNo ratings yet

- A Christian Understanding of Pain and SufferingDocument20 pagesA Christian Understanding of Pain and SufferingSam VargheseNo ratings yet

- Primal Religious Beliefs and Practices - Docx FinlDocument13 pagesPrimal Religious Beliefs and Practices - Docx FinlToshi ToshiNo ratings yet

- Old Testament ProphetsDocument19 pagesOld Testament ProphetsAaron Manuel MunarNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three Consecrated Life - A Special CallDocument9 pagesChapter Three Consecrated Life - A Special CallVivin RodrhicsNo ratings yet

- Brief Study of Paul's Theology of LoveDocument11 pagesBrief Study of Paul's Theology of Lovesenghpung24No ratings yet

- What Are The Names and Titles of The Holy SpiritDocument2 pagesWhat Are The Names and Titles of The Holy Spiritnigel100% (2)

- Preface To The English Protestant EditionDocument50 pagesPreface To The English Protestant EditionGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Evangelism and Missions: Case StudyDocument22 pagesEvangelism and Missions: Case StudyFiemyah Naomi100% (1)

- "Book of Titus" SummaryDocument2 pages"Book of Titus" SummaryRobertNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of WorshipDocument4 pagesThe Meaning of WorshipGolla VamseeNo ratings yet

- 1-Annointing of The SickDocument3 pages1-Annointing of The SickCelestine MarivelezNo ratings yet

- Birth of The ChurchDocument15 pagesBirth of The ChurchChristian AngeloNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 Revelation NotesDocument13 pagesLesson 5 Revelation NotesRosemenjelNo ratings yet

- John 5:24-30Document5 pagesJohn 5:24-30John ShearhartNo ratings yet

- The Sacrifice of Jesus On The CrossDocument4 pagesThe Sacrifice of Jesus On The CrossGolda_Word_Kom_1635No ratings yet

- Living Life in A Sycamore Tree: Learning From ZaccheusDocument14 pagesLiving Life in A Sycamore Tree: Learning From ZaccheusaimbookNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Death of Jesus The Report of The Theological C 1970Document12 pagesUnderstanding The Death of Jesus The Report of The Theological C 1970Rasta 28No ratings yet

- Eternal Life in JohnDocument7 pagesEternal Life in JohnWilling100% (1)

- 3Document210 pages3aistisvNo ratings yet

- The Promised Messiah and The Miraculous Birth Leader's GuideDocument6 pagesThe Promised Messiah and The Miraculous Birth Leader's GuideAndevie Balili IguanaNo ratings yet

- 18 The Second Coming and Final JudgmentDocument6 pages18 The Second Coming and Final JudgmentTahpehs PhiriNo ratings yet

- Apologetics in The Early Church GroupDocument5 pagesApologetics in The Early Church GroupwilliamNo ratings yet

- Pentecost Ph.D. ThesisDocument205 pagesPentecost Ph.D. ThesisMickey PentecostNo ratings yet

- Graham TwelftreeDocument4 pagesGraham TwelftreeincolublewinNo ratings yet

- Creativity Understanding Man As The Imago Dei (Theology Thesis)Document116 pagesCreativity Understanding Man As The Imago Dei (Theology Thesis)Zdravko JovanovicNo ratings yet

- The Covenant of CreationDocument9 pagesThe Covenant of CreationGrace Church ModestoNo ratings yet

- 1998 - Robert L. Deffinbaugh - Highlights in The Life and Ministry of Jesus Christ (Lessons)Document338 pages1998 - Robert L. Deffinbaugh - Highlights in The Life and Ministry of Jesus Christ (Lessons)buster301168No ratings yet

- Unit 4 Study GuideDocument3 pagesUnit 4 Study Guideapi-291848869100% (1)

- Letter of St. Paul - ThessaloniansDocument17 pagesLetter of St. Paul - ThessaloniansFrancis Tan Espera100% (1)

- Mission and Soteriological UnderstandingDocument8 pagesMission and Soteriological UnderstandingRin KimaNo ratings yet

- Note On Eschatology Unit 1Document12 pagesNote On Eschatology Unit 1Vivek SlpisaacNo ratings yet

- Perspectives On The Lord's TableDocument85 pagesPerspectives On The Lord's TableProf.M.M.Ninan100% (3)

- Mission of The Church at 21st CenturyDocument6 pagesMission of The Church at 21st CenturyRev. Jacob Antony koodathinkalNo ratings yet

- 06 Are You A Disciple of JesusDocument2 pages06 Are You A Disciple of JesusJhon Ray OtañesNo ratings yet

- The Symbolism in Book of RevelationDocument15 pagesThe Symbolism in Book of RevelationdivinohenriqueNo ratings yet

- Community of DisciplesDocument116 pagesCommunity of DisciplesJezeil DimasNo ratings yet

- Thesis 9 1Document8 pagesThesis 9 1Victor BoniteNo ratings yet

- (A) Revelation: SECTION 1-BibliologyDocument15 pages(A) Revelation: SECTION 1-BibliologyBrandon CarmichaelNo ratings yet

- Sermon Title:: Five Ways To Draw Closer To JesusDocument4 pagesSermon Title:: Five Ways To Draw Closer To JesusOscar RiveraNo ratings yet

- Book of Uncommon PrayerDocument16 pagesBook of Uncommon Prayerapi-251483947100% (1)

- Close Encounters: An Examination of UFO ExperiencesDocument9 pagesClose Encounters: An Examination of UFO ExperiencesJulia BąkowskaNo ratings yet

- The Story of Zerubbabel-Libre PDFDocument3 pagesThe Story of Zerubbabel-Libre PDFShawki ShehadehNo ratings yet

- Synoptic GospelsDocument57 pagesSynoptic Gospelsodoemelam leoNo ratings yet

- The Wisdom of Jesus Christ in The Book of ProverbsDocument2 pagesThe Wisdom of Jesus Christ in The Book of ProverbsPhillip Ross100% (3)

- Adolf Eichmann: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument11 pagesAdolf Eichmann: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaMircea BlagaNo ratings yet

- Watchtower: 2017 Jehovah's Witnesses Convention - Don't Give Up!Document8 pagesWatchtower: 2017 Jehovah's Witnesses Convention - Don't Give Up!sirjsslutNo ratings yet

- Chukas Parsha MathDocument2 pagesChukas Parsha MathRabbi Benyomin HoffmanNo ratings yet

- The Mission of Elias (Leo Schaya) PDFDocument9 pagesThe Mission of Elias (Leo Schaya) PDFIsrael100% (1)

- CRITICAL REVIEW Jewish Annotated New TestamentDocument2 pagesCRITICAL REVIEW Jewish Annotated New TestamentscaricascaricaNo ratings yet

- Lirik Lagu Rohani BaratDocument8 pagesLirik Lagu Rohani BaratDadang Riankusuma TogelaNo ratings yet

- Thinking Like A Hebrew by Morris SalgeDocument14 pagesThinking Like A Hebrew by Morris SalgeSandra Crosnoe100% (1)

- The Last Crusade August 2001Document6 pagesThe Last Crusade August 2001joedixon747No ratings yet

- Find Out MoreDocument25 pagesFind Out Moreosoh BisehNo ratings yet

- KCT Ad Book 5774 PDFDocument92 pagesKCT Ad Book 5774 PDFSkokieShulNo ratings yet

- 9781567183245Document836 pages9781567183245Kennedy NóbregaNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 9 English-How I Taught My Grandmother To ReadDocument2 pagesCBSE Class 9 English-How I Taught My Grandmother To ReadMuralidhara NayakNo ratings yet

- Business Plan - Catering ServicesDocument49 pagesBusiness Plan - Catering Serviceshandoko88No ratings yet

- 4Q374 - Louis FletcherDocument18 pages4Q374 - Louis FletcherCarlos Montiel100% (1)

- Pengaruh Targum Dan Talmud Dalam Perjanjian Baru: Ps. Dr.C. Jozeph Paul Zhang, MTHDocument41 pagesPengaruh Targum Dan Talmud Dalam Perjanjian Baru: Ps. Dr.C. Jozeph Paul Zhang, MTHBoncel Silo CaleqNo ratings yet

- 252 1 PDFDocument474 pages252 1 PDFAnonymous roNJIpvNo ratings yet

- Words of PowerDocument2 pagesWords of Powerraulaguirre666100% (2)

- Full Gospel Lighthouse Church March 2010 NewsletterDocument2 pagesFull Gospel Lighthouse Church March 2010 NewsletterPastor Daniel BossidyNo ratings yet

- Scripture Memory Plan With VersesDocument6 pagesScripture Memory Plan With VersesadrimirNo ratings yet

- B 001 026 713 PDFDocument592 pagesB 001 026 713 PDFChis Timotei-PaulNo ratings yet

- BereshitDocument5 pagesBereshitMatheus FalcãoNo ratings yet

- The Parable of Laborers of The VineyardDocument30 pagesThe Parable of Laborers of The VineyardJoiche Itallo Luna100% (2)

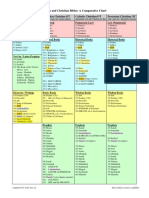

- Heb-Xn-Bibles ChartDocument2 pagesHeb-Xn-Bibles ChartJhada BainNo ratings yet

- Bible Studies-FellowshipDocument12 pagesBible Studies-FellowshipSamuel Adu-Poku100% (1)

- The 99th MonkeyDocument314 pagesThe 99th Monkeybastian1976100% (2)

- Biblical Hebrew CalendarDocument15 pagesBiblical Hebrew Calendarmetroid4everNo ratings yet

- Family Kabbalat Shabbat PacketDocument4 pagesFamily Kabbalat Shabbat PacketPurim HeroNo ratings yet

- Annie Johnson FlintDocument2 pagesAnnie Johnson Flintpatkhsheng@hotmail.com100% (1)