Professional Documents

Culture Documents

People Who Stutter Show Abnormal Brain Activity When Reading and Listening

Uploaded by

Danielle CristóvãoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

People Who Stutter Show Abnormal Brain Activity When Reading and Listening

Uploaded by

Danielle CristóvãoCopyright:

Available Formats

Abstract 563.19 Summary Senior author: Kate E.

Watkins, PhD University of Oxford Oxford, United Kingdom (44-18) 6522-2581 kate@fmrib.ox.ac.uk

People Who Stutter Show Abnormal Brain Activity When Reading and Listening Study suggests abnormalities exist in speech processing as well as production A new imaging study finds that people who stutter show abnormal brain activity even when reading or listening. The results suggest that individuals who stutter have impaired speech due to irregular brain circuits that affect several language processing areas not just the ones for speech production. The research was presented at Neuroscience 2010, the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience and the worlds largest source of emerging news about brain science and health. Stuttering affects about one in every 20 children; most grow out of it, but one in five continues to struggle. While the particular cause of stuttering is still unknown, previous studies showed reduced activity in brain areas associated with listening, and increased activity in areas involved in speech and movement. In the new study, researchers considered whether irregular activity would also be apparent when stuttering speakers silently read. If those patterns are also abnormal, the differences could be considered typical of the stuttering brain and not just the result of the difficulties that people who stutter have with speech production, said senior author Kate Watkins, PhD, of the University of Oxford. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Watkins and her team compared the brain activity in 12 adults who stutter with 12 adults who do not. The researchers conducted the scans in three trials: in one, volunteers simply listened to sentences; in the second, they read sentences silently; in the third, they read sentences silently while another person read the same sentence aloud. The authors found the stuttering volunteers brains were distinctly different from non-stuttering speakers in all three tests. The people who stuttered had more activity in auditory areas when listening only. When reading, there was less activity in motor areas, specifically a circuit involved in the sequence of movement. Our findings likely reflect that individuals who stutter have impaired speech processing due to abnormal interactions in brain circuits, Watkins said. In future studies, it will be important to examine changes in these brain areas in young children to find out if these interactions result from a lifetime of stuttering or point toward the cause of stuttering itself. Research was supported by the U.K. Medical Research Council. Scientific Presentation: Tuesday, Nov. 16, 1011 a.m., Halls BH

563.19, Abnormal brain activation patterns in developmental stuttering during listening and covert reading J. ERB1,2, P. M. GOUGH2, D. WARD3, K. E. WATKINS4; 1Univ. Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France; 2FMRIB Ctr., Univ. of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; 3 Univ. of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom; 4Exptl. Psychology, Univ. Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom TECHNICAL ABSTRACT: Previous functional imaging studies involving overt speech tasks have identified abnormal activity in the language and motor areas of people who stutter (PWS). One study using PET in four PWS suggested that stuttering-related brain activation patterns could be replicated using covert speech (Ingham et al., 2001). Abnormal brain activity observed during covert speech could be considered characteristic of the stuttering brain rather than simply reflecting differences related to the motor symptoms that accompany stuttered speech. The present brain imaging study was designed to examine whether covert speech produced the same abnormal brain activation patterns as overt speech in PWS. In twelve PWS and 17 controls, functional MRI was used to investigate the neural correlates of (i) reading covertly, (ii) passive listening and (iii) reading covertly while listening to the same sentence. In overt speech, stuttering frequency can be dramatically reduced when reading in unison with another speaker, so the third condition was used to mimic this 'chorus effect' for covert speech. For group comparisons, peaks were considered significant at a voxel threshold of Z>2.3, P<0.001, uncorrected. The reading covertly condition revealed reduced activity in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) bilaterally and in the left sensorimotor cortex in PWS relative to controls. While listening to speech, PWS showed increased activity compared to controls in the superior temporal gyrus (STG) bilaterally. During chorus reading, PWS showed reduced activity relative to controls in the putamen and the supplementary motor area (SMA) bilaterally as well as in the left IFG, pars triangularis. The observation of increased activity in the STG bilaterally contrasts with findings from previous studies that robustly report a reduction of activity in the STG in PWS relative to controls during overt speech tasks. It is assumed that this reduction is due to inhibition of auditory areas during self-produced speech. Our findings suggest that the auditory cortex in PWS is abnormally overactive

during speech perception alone. The abnormal activity observed in the putamen and the SMA of PWS is consistent with the hypothesis that stuttering is associated with impairments of the basal ganglia and specifically its outputs to the SMA (Alm 2004). Our data support the conclusion that abnormal neural activation in PWS in speech areas, the basal ganglia and premotor areas can be observed even during covert speech tasks. Yet, these stuttering-related activations and deactivations are different from the neural signatures of stuttering observed previously during overt speech tasks.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Fermentation Process KineticsDocument7 pagesFermentation Process KineticsDillip_subuNo ratings yet

- Ineffective Airway ClearanceDocument1 pageIneffective Airway ClearanceFreisanChenMandumotanNo ratings yet

- Conduction System of HeartDocument2 pagesConduction System of HeartEINSTEIN2DNo ratings yet

- HEMOLYTIC ANEMIAS AND ACUTE BLOOD LOSS: CAUSES, SIGNS, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENTDocument4 pagesHEMOLYTIC ANEMIAS AND ACUTE BLOOD LOSS: CAUSES, SIGNS, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENTAjay Pal NattNo ratings yet

- CurcuminaDocument60 pagesCurcuminaLuis Armando BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

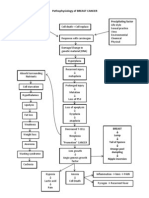

- Pathophysiology of BREAST CANCERDocument1 pagePathophysiology of BREAST CANCERAlinor Abubacar100% (6)

- MSDS Garam MejaDocument5 pagesMSDS Garam MejaDesyrulaNo ratings yet

- Biological Level of Analysis Research GuideDocument45 pagesBiological Level of Analysis Research GuidePhiline Everts100% (2)

- CAFFEINEDocument2 pagesCAFFEINEVALDEZ, Teresita B.No ratings yet

- Infinity Urea Liquid Reagent ENDocument2 pagesInfinity Urea Liquid Reagent ENKouame FrancisNo ratings yet

- Pancreas - Pathological Practice and Research - K. Suda (Karger, 2007) WW PDFDocument329 pagesPancreas - Pathological Practice and Research - K. Suda (Karger, 2007) WW PDFIonut-Stefan CiobaneluNo ratings yet

- 0 - 321113728 Chemistry Investigatory Project On Drugs Addiction Abuse PDFDocument10 pages0 - 321113728 Chemistry Investigatory Project On Drugs Addiction Abuse PDFPardhyuman Bhadu100% (1)

- Psychology 10th Edition Myers Test BankDocument9 pagesPsychology 10th Edition Myers Test Bankbrianwoodsnjyoxepibt100% (12)

- Chapter 04Document72 pagesChapter 04Tony DiPierryNo ratings yet

- Platelet Rich Plasma in OrthopaedicsDocument269 pagesPlatelet Rich Plasma in OrthopaedicsBelinda Azhari SiswantoNo ratings yet

- General Medicine and Surgery For Dental Practitioners - Part 1. History Taking and Examination of The Clothed PatientDocument4 pagesGeneral Medicine and Surgery For Dental Practitioners - Part 1. History Taking and Examination of The Clothed Patientanees jamalNo ratings yet

- Rhopalocera (Butterfly) : FunctionsDocument18 pagesRhopalocera (Butterfly) : FunctionsChris Anthony EdulanNo ratings yet

- Anatomy & Physiology QuestionsDocument10 pagesAnatomy & Physiology Questionskrishna chandrakani100% (2)

- Understanding Meningitis: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument49 pagesUnderstanding Meningitis: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDrAbhilash RMNo ratings yet

- PsychopharmacologyDocument49 pagesPsychopharmacologysazaki224No ratings yet

- Medication AdministrationDocument88 pagesMedication AdministrationKBD100% (1)

- Chronic Cough Differential DiagnosisDocument6 pagesChronic Cough Differential DiagnosisUbaidillah HafidzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document2 pagesChapter 3Rachel Marie M. Gania100% (1)

- Regenesis 1Document14 pagesRegenesis 1White Light100% (3)

- Neuroscience Pathways Fall 2012Document46 pagesNeuroscience Pathways Fall 2012Yezin ShamoonNo ratings yet

- Diagram Human Heart Kel 1Document3 pagesDiagram Human Heart Kel 1Rahma SafitriNo ratings yet

- Euglena BioDocument30 pagesEuglena BioMaddie KeatingNo ratings yet

- PKa LectureDocument26 pagesPKa LectureShelley JonesNo ratings yet

- Arab Board Orthopedic Exam June 2013Document35 pagesArab Board Orthopedic Exam June 2013Nasser AlbaddaiNo ratings yet