Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Korean Culture Social, Moral, and Nutritional Aspects

Uploaded by

steveklasnicOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Korean Culture Social, Moral, and Nutritional Aspects

Uploaded by

steveklasnicCopyright:

Available Formats

Running head: KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL

Korean Culture: Social, Moral, and Nutritional Aspects Steve Klasnic Seton Hill University

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL Abstract Cultural diversity has become increasingly prominent within American society. This phenomenon heightens the need for greater understanding of ethnic groups among individuals,

especially within the medical community. When working with people native to countries outside of the US, it is important for professionals to develop a worldly understanding and compassion for the cultural values of their patients. This essay explores the history, values, and practices of the South Korean nation. It is written with the intent to provide guidelines enabling the provision of the best possible health care.

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL

Table of Contents History of Korean Culture ..............................4 Modern-Day South Korea ...............................5 Education ..........................................................6 Family Dynamics..............................................8 Impact of Religion ............................................9 Traditional Health Beliefs and Practices .....11 Caring for Korean-Americans ......................12 Typical Dietary Preferences ..........................13 Gender and Psychological Disparities..........15 Conclusion ......................................................16

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL Thanks to the discoveries and inventions of modern science, the world is fast becoming one. No one part of the world is ever too far away from another, and it is impossible for any culture to live outside the influence of its global peers. Since the last world war, most problems

dealing with humanity have become global issues. Whether those problems concern health, food, or education, the world must be viewed from vastly different cultural perspectives. There is a currently more need to become more culturally, racially, and ethnically diverse than any other time in our history. This change forces the worlds people to inherit a sense of multiculturalism to survive in the modern world. This inherent sense is particularly important for those working within the medical field. For one to provide a full spectrum of care to patients, an understanding of both a past and current cultural identity is integral. The aim of this paper is to develop a holistic model of dietetic healthcare in regard to Korean-Americans, with specific emphasis on cultural identity, dietary preference, and social interaction. It is hypothesized that a capable understanding of afore mentioned qualities will lead to the provision of exceptional nutritive care. South Korea has a long and rich history, as do many of the Asian cultures. Korea is known as the Land of the Morning Calm. Koryo means high and clear, symbolizing the clear blue sky of South Korea. The beautiful nature of the country is expressed through this ancient name. There have been human remains recovered as far back as 100,000 BC, and cultural and human societal structures are estimated to have been in existence since around 10,000 BC. For centuries Korea has long been an isolated country, and its people have traditionally not been welcoming to the presence of other cultures. The myth of Korea's foundation by the god-king Tangun embodies the homogeneity and self-sufficiency valued by the Korean people.

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL

During the later period of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) this isolationist policy earned it the Western nickname of the "Hermit Kingdom". However, by the latter part of the19th century, Korea became the object of great contention for the colonial ambitions of both Japan and Europe. By the year 1910, Korea was annexed by Japan and remained occupied until the end of World War II. (Cumings, 2005) A republic was set up in the southern half of the Korean Peninsula, after World War II, while at the same time a communist-style government was established in the north. During The Korean War (1950-53), the United States and other United Nations forces interfered to defend South Korea from North Korean attacks, which were supported by the Chinese. In 1953, a peace agreement was signed dividing the peninsula. South Korea then after attained rapid economic growth with a per capita income thirteen times the level of North Korea. Furthermore, the nation suffered a severe financial crisis in 1997, from which it continued to make a firm revival and maintain its commitment to democratize its political processes (Cumings, 2005). The culmination of various events have attributed to the infusion of ideas present in current-day South Korea. Modern-Day South Korea When depicting other cultures, it is crucial to consider location and the direct impact in which that procures on various aspect of life. South Korea occupies the southern half of the Korean Peninsula in eastern Asia. To put the size of this nation into perspective, it is slightly larger than the state of Indiana. Within those confines reside over 48 million people. Arable land is limited in South Korea. The staple of agriculture is rice, which subsequently plays a major role in diet. Most other foods come as imports, many from the United States ("South Korea Economy," 2011).

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL Manufacturing has been the engine of growth and development for South Korea, which has emerged as a major supplier of various manufactured products. Currently South Korea is a booming internationally relevant economy, surpassing the US in GPD growth. South Koreas economic profile has won a string of plaudits, including: Asias largest oil exporter, worlds

largest shipbuilder, worlds fastest increase in patents registered, worlds largest manufacturer of screen displays, and worlds highest internet connectivity ("South Korea Economy," 2011, para. 2). In essence, South Korea is a democracy that functions analogously to the United States. One major difference between the U.S. and South Korea is the amount of diversity among citizens. South Korea is currently in pursuit to break its ancient trend of homogeneity, and become a more heterogeneous and multicultural society. Wontedly, immigrants are subject to discrimination and excluded from the very ethnocentric Korean society. There is also prevalent abuse in terms of universal human rights concerning foreign ethnical groups (Kang, 2010). By virtue of the U.S. being an extremely heterogeneous nation, this cultural difference is one of vital importance. Although Korea is headed in a more congeneric direction, the adaptation has thus far proved laborious. There is a growing consensus that a diversification of the education system could help bridge the gap. Education Traditionally, in South Korea the teaching profession has been regarded as an honorable job, a view that is rooted in Confucianism, a foundation for Korean cultural values. (Kang & Hong, 2008, p. 202) Confucius once said, King, teacher, and parents are equal. This digest denotes the high esteem and respect the Korean culture has traditionally placed on education and those who provide it. This respect is still prevalent within the culture, enabling Koreans to far surpass Americans in areas such as math and science. Koreans are routinely subjected to larger

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL class sizes, yet yield higher results on standardized tests than students in the United States. Ironically, Korean teachers ordinarily spend less than half the time in the classroom as their American counterparts, yet still attain a higher average salary (Kang & Hong, 2008). The Confucian belief in success through hard work, economic emphasis on developing human resources, and the role of educators has created tremendous enthusiasm for education in South Korea (Kang & Hong, 2008). Above all, the culture places a great emphasis on learning, and students typically look at education as a pathway to success. Over the past few decades, one of the most important driving forces for change in higher education has been internationalization. As previously mentioned, Korea has typically

experienced complications concerning intermixing with other cultures. In recent years, they have come to realize that being globally relevant was imperative for their success. Despite some success, Korea has experienced a steady decline in birthrate over the past two decades. This has created a greater need for diversification in order to allow colleges and universities to continue to maintain operations. (Byun & Kim, 2010). Universities, particularly private institutions receiving less government aid, have been forced to recruit on an international level to survive from a fiscal standpoint. Given the evergrowing interconnectedness of countries around the world, the internationalization of Korean higher education seems an inevitable for Korea to become a educational hub for Asia. Be that as it may, Korea will need to develop a more welcoming environment for the international community for success to be prevalent (Byun & Kim, 2010). Exploring the family unit is conducive for helping to understand many of the vast cultural differences.

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL Family Dynamics

The Korean family has traditionally remained devoted to Confucian values by producing children to maintain and support the paternal family line, but in South Koreas transition to a low birth rate, an increasing number of couples have remained childless. The typical Korean family typically aggregates around the children. Parents are expected to devote their energy, time, and money to raise and educate children. The strong connections between parents and children continue after children marry because children often support their elderly parents. The society is strongly influenced by Confucian principles. This influence can be seen in families, schools, films, television drama, the mass media, and religious institutions (Yang, 2008). There are few nursing homes or assisted-living facilities in South Korea because younger family members ordinarily provide care for their elders. It is considered to be shameful for needy elders not to receive care and support from younger family members. In the Korean version of Confucian family values, women traditionally provide most of the care for elderly in-laws. In recent times, women have been providing more care for their own parents as well. (Yang, 2008) The younger generation, particularly women, find this system to be unacceptable. Women of all ages are critical of the way Korean Confucianism promotes patriarchal family and societal values. Women bear primary responsibility for childcare. Women who work hard to achieve a high level of education and a career are typically forced to cast their accomplishments aside when children are born. The coupling of an increasing number of women desiring to advance their careers, with the unwillingness of men to aid in childcare, has presented complications for many Koreans. Researchers contribute both the decrease in fertility and declining popularity of Confucianism to this quandary (Yang, 2008).

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL Because Korea is child-centric, the social dynamic is very different from that of the US.

The younger generation feels obligated to provide grandchildren for their parents. It is viewed as irresponsible and selfish to be in a childless relationship. All generations in the society believe that a happy family is one that incorporates children. (Yang, 2008) Unlike Western culture that encourages children to move away from home and support themselves tout de suit, Korean family units remain together, in many cases, up until children marry (Shin & Nam, 2004). This lengthened period of co-existence provides a foundation for parents to continue to play a role in the maturation of children for an extended period of time. This prolonged connection typically yields extremely respectful children as well as supportive parents. It is not that Korean families do not emphasize independence and self-awareness. Rather, parents are present to shepherd their children in the right direction and provide the necessary instruments for success, regardless of cost (Shin & Nam, 2004). The Korean attitude regarding children is in many ways a direct product of their Confucian-based religious belief system. Impact of Religion in Society Kims (2003) study presented the following: For 500 years, Korea adopted Neo-Confucianism as its official ideology and strove to create a Neo-Confucian state by following its precepts as closely as possible. Neo-Confucians believed the body was sacred. Since it was bequeathed by ones parents, in accordance with filial piety, the body had to be respected and remain unaltered. (p. 99) Followers of Neo-Confucianism postulate being selfless and living without ego. The code is based on an idea of ki, the essential force that is believed to link mind and body. There is no distinction between the self and the universe. Neo-Confucian men are encouraged to let go

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL of ego and become selfless. The said directive is consummated by breaching individual consciousness and procuring the ability to separate self from others (Kim, 2003). Considering many of the nations laws are constructed from religious principles,

10

understanding the culture from a standpoint of religious proclivity is imperative. Neo-Confucian techniques of self-cultivation of the mind and body apply only to men. Women in NeoConfucian society are incapable of achieving sagehood and therefore traditionally have had neither the desire nor the ability to strive for transcendence of the self and body. (Kim, 2003) Wistfully, in many cases, women are treated as second-class citizens. They are seen as objects necessary for procreation, and do not garnish the respect of their male counterparts. Korean women are expected to appear aesthetically perfect in the eyes of the men. South Korea has the highest ratio of cosmetic surgeons to citizens in the world. It is not uncommon for women to have plastic surgery before graduating high school. These views all hinge on the teachings of Neo-Confucian thought (Kim, 2003). Although Confucian values are deeply embedded within the society, Christianity is becoming prevalent as South Korea becomes more tantamount to the Western thought. Buddhism is also common practice among sectors of the denizens of Korea. The over-riding concern of most Koreans, outlying religious affiliation, seems to stem from acquiring the ability to live a healthy and happy life. In a survey comparing older and younger generations with respect to what they considered was important in life, the top two answers were health (19.8%) and financial stability (16.7%) (Shim, 2000). As a result of this affinity for well-being, it is imperative to understand the manner in which Koreans define good health.

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL Traditional Health Beliefs and Practices Korean-Americans are the fastest growing subgroup of Asian Americans, hence great

11

importance is placed on capably understanding traditional and current Korean medical practices. Wontedly, many Koreans, especially elders, may prefer Hanbang also known as Hanyak, as well as Oriental medicine, as the preferred method of health care (Shin, Shin, & Blanchette, n.d.). These methods are based on Chinese health care and are centered on the idea of balance. The four customary traditional treatment methods are acupuncture, herbal therapy, moxibustion, and cupping. Most traditional Korean practices involve naturalistic rituals that attempt to rid the body of anything plaguing it. Acupuncture, for example, involves the insertion of extremely thin needles in your skin at strategic points on your body. Korean theory explains acupuncture as a technique for balancing ki (Kim et al., 2005). Korean patients may alternate between practitioners of Western and traditional Korean medicine, although each type of practitioner may discourage patients from seeing the other (Shin, Shin, & Blanchette, n.d.). One conceptualization of illness is the interruption of the flow of life energy and blood, or Ki. Koreans attach weight to the idea of spiritual causes of illness. If spiritual expectations fail to be met, disease is reckoned to occur as a result. (Shin, Shin, & Blanchette, n.d.). It is believed that illness is often caused by a mere lack of spirituality. Reasons include failure to pray, failure to express emotions, and displeasing diseased ancestors. Considering that Koreans place such high value on family, it is not uncommon to put advice of a family member or friend above that of a medical professional. Concerning end of life decisions, Koreans typically prefer to die at home around family. Under Confucian belief, death

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL is seen as a virtuous passage into another life. Family members, especially the oldest son, are likely to be present when elders are near death (Shin, Shin, & Blanchette, n.d.).

12

Due to the patriarchal nature of the Korean people, health issues concerning men receive more attention than those of women. In consequence of this fact, it would be opportune to develop an understanding concerning the nature of what both Korean men and women expect from a health care provider. As a health care provider in any environment, it is essential to have knowledge regarding the culture of all patients under supervision. Caring for Korean-Americans Often Korean patients are more inclined to seeing medical professionals of the same gender. Koreans generally act with inordinate respect in regard to professionals, and expect the same courtesy in return. It is not uncommon, however, to bear a language setback when attempting to communicate with Korean Americans. Often, both language skills are the ability to communicate with people which whom they are unfamiliar, are subpar. High value is placed on work ethic in the Korean society. Regardless of any language barriers, they expect to see a busy and hard-working staff. (Shin, Shin, & Blanchette, n.d.) Within the span of 12 years, South Korea went from private voluntary health insurance to government-mandated universal coverage. Because they live in a nation where the healthcare system is nationalized, it is not uncommon for Korean-Americans to lack understanding of the US health care system. Hospitalization may be especially undesirable for various reasons. For example, the unwillingness for patients to separate from family, lack of Korean-speaking staff as well as Korean food in hospitals, and inability to afford care, are the most prevalent complaints (Lee, 2003).

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL It is estimated that 70-85% of Korean-Americans attend church on a regular basis. The high attendance of these establishments, coupled with a perceived increase in comfort, could make churches an encouraging atmosphere to offer nutritional counseling. Because there are a prevalent amount of Korean-Americans who do not speak English, the church also provides a setting in which bi-lingual translators could be used (Jo, Maxwell, Yang, & Bastani, 2010). Most Koreans prefer natural methods of improving health, such as diet, consuming uncooked or natural foods, and increasing exposure to nature. The goal of a typical KoreanAmerican is only to use Western medicine when more traditional methods fail. From the

13

perspective of a dietitian, Korean ideals seem to allude to the fact that they would be receptive to the criterion of counseling. (Shin, Shin, & Blanchette, n.d.). With this preference in mind, it becomes impertinent to understand the typical Korean diet in comparison to that of the U.S. Typical Dietary Preferences Korean Americans tend to adopt the Western eating habits of consuming more animal protein, fats, and refined sugar while still maintaining traditional Korean eating habits of consuming hot, spicy, and salty dishes (Shin & Lach, 2011, p. 163). Examples of popular dishes include steamed rice, kimchi, and a soy sauce stew, all of which are rich in both sodium and carbohydrates. Korean-Americans generally consume less fruits and vegetables, as well as more snacks, than ancestors from the homeland. The more Koreans permeate into American society, the more at-risk they become for chronic disease. Traditionally Koreans have a very low risk for obesity. However, they are often at high risk for diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. The rate at which these conditions are found typically increases as Koreans age. Among Korean Americans aged 18 to 50, the prevalence of hypertension is 12% whereas it is 53% among those aged 50 to 89. Despite the

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL

14

rising incidence of type 2 diabetes in Korean immigrants, little is known about glucose control in these individuals (Shin & Lach, 2011). Recently studies have confirmed that Korean-Americans are not outstandingly healthy eaters. In fact, one study comparing all U.S. immigrants on the basis of dietary habits concluded the eating habits of Korean-Americans were the unhealthiest. Particular concerns are consuming a diet rich in sodium and calorie while maintaining a low intake of dairy products (Shin & Lach, 2011). Korean-Americans regularly skip breakfast, and eat more red than white meat, both of which have been linked to various health conditions. A study by Song (2004) concluded that there is a definitive link between excess consumption of red meat and prevalence of type II Diabetes. With the extreme oscillation of Diabetes type II found within the Korean-American community, the current nutritional approach needs to be revised. A combination of relevant nutritional education combined with healthfully designed modifications of traditional Korean recipes, could be a viable solution. (Shin & Lach, 2011) Among all the worlds ethnicities, the Asian people have the highest rate of lactose intolerance. The apparent convergent evolution of lactase persistence among human populations is an adaptive response to the domestication of dairy animals and consumption of milk during adulthood. After the beginning of dairy farming there would have been an advantage for those individuals who had high levels of intestinal lactase. Lactase persistence is common in the areas with long traditions of dairy farming. Cultures without a history of regular dairy consumption are more likely to inherit a recessive gene causing intolerance. In essence, the ability to digest lactose is an evolutionary adaption that has been historically absent in the Asian culture. It is estimated that up to 90% of Asians are unable to digest lactose (Holden & Mace, 2009). There

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL have been numerous studies attempting to decipher the apparent connection between ethnicity, gender, and the psychological factors that can affect dietary patterns. Gender and Psychological Disparities

15

Korean-Americans are unique in the way that mental health, rather than physical health, was more useful in the prediction of healthy eating practices. Often times Koreans are emotional eaters, one study found that better mental capacity led to healthier eating patterns among KoreanAmericans. It is apparent that nutritional intervention is necessary for many Korean-Americans attempting to transition to the US way of life. Interventions should primarily focus on slowly decreasing sodium and carbohydrate intake while synchronously increasing dairy consumption. These dietary changes can be difficult for individuals who wish to retain traditional Korean cultural practices (Shin & Lach, 2011). It is recognized that Korean-Americans, among other immigrants, are more likely to develop mental health problems in comparison to Caucasians, yet far less likely to pursue professional help. Korean-Americans have been found to be more at-risk for mental distress than any other ethnic group. Many Korean-Americans attribute both mental and physical conditions as signs of weakness, and refuse to utilize professional help. Based on Confucian ethics, KoreanAmericans tend to believe that self-concealment of emotions is a virtue. This attitude is deeply embedded within the patient, creating a situation in which there is often a failure to attain help. When counseling a Korean-American in any area of medical practice, it is important to understand this belief system in order to thoroughly work through issues (Jang, Chiriboga, & Okazaki, 2009). Dietary practices of Korean women are candidly considered to be more healthful than those of Korean men. Korean women customarily tend to consume more fruit and vegetables on

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL a daily basis. Korean women are also more inclined to make dietary changes for both aesthetic and health-related reasons. One study concluded that women appeared to have a different

16

motivational structure than men when attempting to adhere to a low-fat/high-vitamin diet. When asked, the women studied were admittedly more concerned with personal health risks such as blood pressure, cholesterol level, and body weight in comparison to the men. When developing dietetic intentions, it was more plausible for women to follow through by implementing changes via a working plan. The study also found that women typically eat healthier than men, however, married people eat the healthiest. Ironically, there is a higher prevalence of obesity in KoreanAmerican women as opposed to men (Renner et al., 2008) Conclusion This paper sought to analyze the Korean culture and its implications of cultural influence that affect the attitude, culture, and essentially the diet of Korean-Americans. Studies show that culturally competent nutritional education and care has resulted in positive dietary and overall lifestyle changes. Motivated patients of a common ethnicity can sometimes present complications, however, when working with foreign patients, it is essential that efforts be made to understand alternative cultural norms. Certain racial and ethnic groups face unique challenges due to strong cultural influences on diet, South Korea being a classic example. Typical problematic areas of the Korean-American diet include excessive sodium and caloric intake coupled with a near complete lack of dairy consumption. For Korean-American patients seeking nutritional help, the most common challenges associated with following dietary recommendations are difficulty communicating with providers about diet, as well as the general ability and unwillingness to change. Therefore,

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL

17

culturally competent care for patients with dietetic issues should address more than ethnic food preferences; it should address all potential dietary obstacles. Steps can be taken in attempt to provide the best care possible for Korean-American patients. Procurement of resources such as cookbooks, support groups, classes and community programs relevant to fixing specific known health issues concerning Korean-Americans would be an efficient starting point. As afore mentioned, the church is an area in which KoreanAmericans tend to be more receptive to acquiring knowledge, based on an increased level of comfort. Using this venue to assess dietary habits as well as counsel patients could prove to aid in achieving monumental success. As part of the public health system, Registered Dietitians must promote change at family and community levels to best serve international patients.

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL References Byun, K., & Kim, M. (2010). Shifting patterns of the governments policies for the internationalization of Korean higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 15, 468-488. doi: 10.1177/1028315310375307

18

Cumings, B. (2005). Koreas place in the sun: A modern history (Updated Ed.). W. W. Norton. Holden, C., & Mace, R. (2009). Phylogenetic analysis of the evolution of lactose digestion in adults. Human Biology, 81, 597-619. doi: 10.3378/027.081.0609 Jang, Y., Chiriboga, D., & Okazaki, S. (2009). Attitudes toward mental health services: Agegroup differences in Korean American adults. Aging Mental Health, 13, 127-134. doi: 10.1080/13607860802591070 Jo, A. M., Maxwell, A. E., Yang, B., & Bastani, R. (2010). Conducting health research in Korean American churches: perspectives from church leaders. Journal of Community Health, 35, 156-164. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9213-1 Kang, N., & Hong, M. (2008). Achieving excellence in teacher workforce and equity in learning opportunities in South Korea. Educational Researcher, 37, 201-208. doi: 10.3102/0013189X08319571 Kang, S. (2010). Multicultural education and the rights to education of migrant children in South Korea. Educational Review, 62, 287-300. Retrieved from EBSCOhost Kim, T. (2003). Neo-Confucian body techniques: Womens bodies in Koreas consumer society. Body & Society, 9, 97-113. doi: 10.1177/1357034X030092005 Kim, Y. S., Jun, H., Chae, Y., Park, H. J., Kim, B. Y., Chang, I. M.,...Lee, H. J. (2005). The practice of Korean medicine: An overview of clinical trials in acupuncture. Advance Access Publication, 3, 2-28. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh102

KOREAN CULTURE: SOCIAL, MORAL, AND NUTRITIONAL Lee, J. (2003). Health care reform in South Korea: success or failure? American Journal of Public Health, 93, 48-51. Retrieved from EBSCOhost Renner, B., Kwon, S., Yang, B. H., Paik, K. C., Kim, S. H., Roh, S.,...Schwarzer, R. (2008). Social-cognitive predictors of dietary behaviors in South Korean men and women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15, 4-13. doi: 10.1080/10705500701783785 Shim, J. (2000). Buddhism and the modernization process in Korea. Social Compass, 47, 541548. doi: 10.1177/003776800047004006 Shin, C., & Lach, H. (2011). Nutritional issues of Korean-Americans. Clinical Nursing Research, 20(162), 162-180. doi: 10.1177/1054773810393334

19

Shin, E. H., & Nam, E. A. (2004). Culture, gender roles, and sport : The case of Korean players on the LPGA tour. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 28, 223-244. doi: 10.1177/0193723504266993 Shin, K. R., Shin, C., & Blanchette, P. L. (n.d.). Health and health care of Korean-American elders. Retrieved from http://www.stanford.edu/group/ethnoger/korean.html Song, Y., Manson, J. E., Buring, J. E., & Liu, S. (2004). A prospective study of red meat consumption and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly women. Diabetes Care, 9, 2108-2115. Retrieved from EBSCOhost South Korea Economy. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.economywatch.com/world_economy/south-korea/ Yang, S. (2008). Confucian family values and childless couples in South Korea. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 571-592. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07309462

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- ISPA 2006 The Financial RealityDocument13 pagesISPA 2006 The Financial RealitysteveklasnicNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Essential Consulting FormsDocument7 pagesEssential Consulting FormsstaffilesjnNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- EAL Worksheet Nutrition SemDocument5 pagesEAL Worksheet Nutrition SemsteveklasnicNo ratings yet

- Food Science Pro Article AnalysisDocument3 pagesFood Science Pro Article AnalysissteveklasnicNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Foods I FinalDocument3 pagesFoods I FinalsteveklasnicNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Med Term Final Study GuideDocument2 pagesMed Term Final Study GuidesteveklasnicNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Who Killed Fatima.Document6 pagesWho Killed Fatima.raeesmustafa100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Wait For The LORD Sermon Detailed OutlineDocument5 pagesWait For The LORD Sermon Detailed OutlineDoug McFallNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- KSWA requests inclusion of "SARNADocument1 pageKSWA requests inclusion of "SARNAGaneswarMardiNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

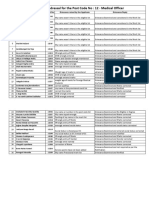

- Post Code-12 Medical OfficerDocument25 pagesPost Code-12 Medical OfficerDr.vidyaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Path To Becoming A Modern Master by Deborah King WorkbookDocument9 pagesThe Path To Becoming A Modern Master by Deborah King WorkbookEmiNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- AdPro Dombey & SonDocument1 pageAdPro Dombey & SonDarwin ThinakaranNo ratings yet

- WORD SEARCH (Chocolates Names) There Are 30 Tithis in Each Lunar Month: Krishna Paksha (Dark Fortnight) Shukla Paksha (Bright Fortnight)Document1 pageWORD SEARCH (Chocolates Names) There Are 30 Tithis in Each Lunar Month: Krishna Paksha (Dark Fortnight) Shukla Paksha (Bright Fortnight)Sravan ReddyNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Makalah Bahasa Inggris Analisis First TravelDocument12 pagesMakalah Bahasa Inggris Analisis First TravelRicky ChandraNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- TheGospels Lesson1 Manuscript EnglishDocument39 pagesTheGospels Lesson1 Manuscript EnglishCláudio César Gonçalves100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Guide To Crafting Personal Legacy Statements - An Ancient Legacy Tool of The Wealthy & WiseDocument20 pagesA Guide To Crafting Personal Legacy Statements - An Ancient Legacy Tool of The Wealthy & WiseDon West Jr.100% (2)

- Toh984 84000 The Usnisavijaya DharaniDocument45 pagesToh984 84000 The Usnisavijaya DharaniVoid ReaPNo ratings yet

- Aglow International Gods-LoveDocument5 pagesAglow International Gods-LoveRolwynloboNo ratings yet

- Effect of SpiritualityDocument1 pageEffect of SpiritualityAlina AltafNo ratings yet

- Mahabaratha Tatparya Nirnaya: - Introduction by Prof.K.T.PandurangiDocument4 pagesMahabaratha Tatparya Nirnaya: - Introduction by Prof.K.T.PandurangiSoumya Ravi BNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- EuergetismDocument173 pagesEuergetismsemanoesisNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Jesus (PBUH) Did Not Die According To QuranDocument6 pagesJesus (PBUH) Did Not Die According To QuranManzoor AnsariNo ratings yet

- Seema v. Ashwani KumarDocument5 pagesSeema v. Ashwani Kumarivin GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Saktong Buhay: Sa Dekalidad Na Edukasyon Pinanday.Document2 pagesSaktong Buhay: Sa Dekalidad Na Edukasyon Pinanday.Carmel Buniel SabadoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- WebpdfDocument545 pagesWebpdfSusan SmithNo ratings yet

- Introducing the Guest Speaker Nilo Villanueva TejadaDocument3 pagesIntroducing the Guest Speaker Nilo Villanueva TejadaJemmalyn Devis Fontanilla93% (44)

- Liebherr Wheel Loaders l509 g6 0 D 1582 2021-01-26 Service Manual en PDFDocument22 pagesLiebherr Wheel Loaders l509 g6 0 D 1582 2021-01-26 Service Manual en PDFkathryngates090185rjw100% (126)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Christian Scholars Group Statement on Christian-Jewish RelationsDocument4 pagesChristian Scholars Group Statement on Christian-Jewish RelationsSidney DavisNo ratings yet

- Contoh Jurnal T-WPS OfficeDocument10 pagesContoh Jurnal T-WPS OfficeSandro A-ztNo ratings yet

- Who Am IDocument3 pagesWho Am IVia LacteaNo ratings yet

- Thrice-Greatest Hermes, Vol. 3Document300 pagesThrice-Greatest Hermes, Vol. 3Gerald MazzarellaNo ratings yet

- Muslim Law Introduction-1Document20 pagesMuslim Law Introduction-1Sonali AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Opus Magnum - The Great WorkDocument3 pagesOpus Magnum - The Great WorkCristian CiobanuNo ratings yet

- A Study of Life Together by Dietrich BonhoefferDocument10 pagesA Study of Life Together by Dietrich BonhoefferDoug McFallNo ratings yet

- BALUNGAO Accomplishment - ReportDocument28 pagesBALUNGAO Accomplishment - ReportEnitsirc PineNo ratings yet

- 21 Jain LiteratureDocument36 pages21 Jain Literaturenaran solanki100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)