Professional Documents

Culture Documents

New Economic Approaches To The Study Of: Business History

Uploaded by

RS Praveen KumarOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

New Economic Approaches To The Study Of: Business History

Uploaded by

RS Praveen KumarCopyright:

Available Formats

New Economic Approachesto the Studyof BusinessHistory

Naomi R. Lamoreaux and NBER Daniel M.G. Raft

Departments ofHistory Economics, and University ofCa/ifirnia, 4nge/es Los

TheIVharton School, University ofPennsylvania

and NBER

Peter Temin

Department ofEconomics, Massachusetts ofTechnology Institute

and NBER

Business historyis by its very naturean interdisciplinary subject.

Because businesses are first and foremost economic units that make such

decisions howmuchof a goodto produce, to makeit, andwhatto as how charge it, their for behavior nothing notthesubject economic is if of theory. At thesame time,however, businesses organizationspeople are of whose choices areaffected thesocial cultural by and environmentwhich in they andwork. live Henceunderstanding businesses how operated the past- andwhy they in succeeded failed isinevitably interpretive or an activity requires tools that the andsensitivity historical of scholarshipwell. as Unfortunately, is littlecommunication between there today economists andhistorians evenbetween or economic historians (whoarelargely economists training) business by and historians typically (who come of history out departments). former The haveorganized themselves theEconomic into HistoryAssociation; latter the intotheBusiness History Conference. a small Only number people of attend bothsets meetings. of Moreover, twogroups the of scholars largely subscribe and publish different to in journals. Economic historians theJournalEconomic and read of History Explorations inEconomic History, andbusiness historians Business the History Reviem the Conference's and annual publication, Business Economic and History. Thereare relatively articles few in either of journals appeal bothgroups scholars. set that to of

We aregrateful Brace to Kogut, Constance Helfat, Daniel Levinthai, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Kenneth Sokoloff, Sidney Winter, MaryYeager many and for helpful conversations, all theNBERconference to participants theix for enthusiastic engagement, to Martin Feldstein hissteadfast for support, to participants Hagley and in the Museum Library and Conference theFuture Business on of History, especially discussant, Scranton, our Philip for theix thoughtful reactions anearlier to version this of text. Theusual disclaimer applies.

BUSINESSAND ECONOMIC HISTORY, Volume twenty-six, 1, Fall1997. no.

Copyright 1997 bytheBusiness History Conference. 0894-6825. ISSN

57

58 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

Although splitbetween the business history and economic history is particularly at thepresent acute time, canbetraced it back theperiod to before WorldWar II. In thisessay firstdetail history relations we the of between the two groups scholars of sincethe earlytwentieth century. then outlinea We series theoretical of developments we believe, that, nowmakes possible it to bring business economic and historians together thewriting a newkindof in of interdisciplinary business history.In the remainder the essay, use of we examples therecent from literature, especially papers and from given a series at of conferences haveorganized we over the pastfew years, illustrate to the

possibilities new ofscholarship. ofthis style 2

Business Economic History vs.

The fieldof economic history ks formal had beginning the United in States 1892 when Harvardcreated chairin the subject in a and appointed Britishscholar WilliamJ. Ashleyto fill it. A numberof other universities followed Harvard's andestablished lead similar chairs during lastdecade the of thenineteenth century. AftertheFirst World War,a newgeneration scholars of assumed positions leadership, thefieldbegan period rapid of and a of growth. One of the mostimportant the newleaders EdwinF. Gay,who had of was replaced Ashley Harvard whonowwenton to lendhisprestige at and and energies a newprogram institution to of building. Amongthe fruitsof his

efforts were the National Bureauof EconomicResearch, Commission the on

Recent Economic Changes, Commission Recent the on Social Trends, the and Social Science Research Council. Underlying of theseorganizations all was Gay's belief research economic that in history, particularly careful the amassing of long-term quantitative sets, data would provide vitalfoundation both a for historical understanding policy and making. similar For reasons, believed Gay thatit was important archives collect for to business papers, hehelped and to found association an devoted this to end, Business the History Society. of One hisstudents, N.S.B. Gras, firstStrauss the Professor Business of History the at

Harvard Business School,becamea leaderof the new sub-fieldof business

history; from1928to 1931, and GayandGrasco-edited Journal Econoraic the of and Business Histo7, aimof which to bring the was together workin bothsubject areas [Sass, 1986, 15,29-43; pp. Cole,1968, 558-9]. pp. This collaborative effort soon foundered, however, over the very different conceptions twomenhadabout direction scholarship the the that in business history should take.Gayandothereconomic historians the time at believed that business history should contribute the synthetic to view of economic history were they seeking constructthatit was to precisely because businesses subjected the discipline the marketthat their records were to of could provide insight larger into economic processes. on theother Gras, hand,

2The papers fromthefirsttwoconferences been have published respectivelyTernin in [1991] Lamoreaux Raft[1995]. and and Papers froma thirdconference appear a third will in

volume [Lamoreaux, andTemin,forthcoming]. Raft,

NEW ECONOMIC APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 59

hadlittleuse thetype theorizing characterized more for of that the established

field. He was an inductive thinker who believed that businessbehavior should

be studied its ownsake thatnewgeneralizations emerge for and would from the casestudies amassed scholars by doinghighlyfocused research the on internal operationsparticular of enterprises. andGaydisagreed He vehemently aboutthe amount such of workthejournal should publish, the two men and (andtheirrespective fields) became increasingly estranged. resigned Gay his editorial position 1931,and the journal in foldedthe nextyear[Sass, 1986, pp. 42-5;Heaton,1952,p. 194]. Although Grashada number followers, of many scholars interested in thestudy business of history soon grew frustrated theparticularismhis with of approach, for a time,it seemed if there and as wouldbe a reconciliation of business economic and history. Economists ArthurH. Cole,whose like work fell withinboth sub-disciplines,a newwaveof organization led building that culminated thefounding the 1940s theEconomic in in of History Association, theCouncil Research Economic for in History, theCenter Research and for in Entrepreneurial Historyat Harvard[Heaton, 1941;Heaton,1965;Sass, 1986, pp. 54-9]. As the historyof the Centerillustrates, however, whatever

reconciliation that occurred was short-lived.

Scholars the Centerwere interested reinjectmg at in theoryinto the study business of history. many themcame question utilityof But of to the conventional neoclassical economics that purpose. for The starting point of mostresearcherstheCenter Joseph at was Schumpeter's concept entreprenof eurship a creative that in discontinuous as act fashion altered by shifting outward the economy's production possibility frontier[Schumpeter, 1934]. Entrepreneurship an important was subject study, to theyargued, because this kind of creativity the keyto greater was social well-being. Schumpeter himself wasunable explain to why somesocieties some at timesproduce disproportionate numbers entrepreneurs, neoclassical theory of and price alsoappeared to lackanswers such to questions. scholars the Center So at turned instead to sociological (particularly Parsonian) models humanbehavior orderto of in understand somecultures why seemto offer particularly fertilegroundfor entrepreneurial innovation. workof some themostimportant The of historians associated with the center- good examples David Landes, are Thomas Cochran, and Alfred D. Chandler, - consistently Jr. employed concepts and addressed debates theheartof thissociological at literature, evenwhentheydid

not make extensive its use rather vocabulary of arcane and categories ofanalysis. 3

Parson's approach the study society essentially equilibrium to of was an one, and there was nothinginherently incompatible between the broad syntheses business of historydeveloped thesescholars the work of by and

3Thissearch theory for oftentooktheformof writtenscholarly debate thepages in of the Center's in-house journal, Explorations in Entreprenemial History. an excellent For analysis of theprocess whichparticipants by turned Parsonian to sociology, Sass see [1986, 107pp.

223]. ananalysis theutility this For of of body theory of fromsomeone associated a time for

with the center,seeGalambos [1969].

60 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

economic historians trained economics. recent in In years, indeed, economists as prominent OliverWilliamson David Teecehavefoundmuchto as and admire in Chandler's model of the evolutionof business organizations [W'filiarnson, 1981; Teece, 1993]. But circumstances the time made the at differences seemmore important than they actually were.Duringthe early 1950s,concern aboutthe causes underdevelopment laxge of in partsof the worldled to heated debates aboutthe role of entrepreneurshipindustrialin ization. the positive On side, course, of werethe scholars the Center. at The negative waschampioned Alexander side by Gerschenkton, of Harvard, also

who stressed this debate the role of naturalresourceendowments,income in

levels, the sizeof the domestic and market [Abramoritz David,1996,pp. and 50-7]. The spiritof the negative view was essentially of neoclassical that economics, Gerschenkton's and students, alongwith thoseof the equally prominent economist SimonKuznets, formedthe vanguard what cameto of be knownasthe New Economic History(or sometimes Cliometrics), brand a of scholarship committed the systematic to application neoclassical of economic theoryand formalhypothesis testing the studyof the past to [Lamoreaux, forthcoming]. The young scholars led the Cliometrics who movement disparaged the

importance heroic of individuals so, ipsofacto,the entiretopicof and

enttepreneudal history. Theysubscribed instead theviewthattechnological to innovation induced changes relative was by in prices thatis,bymaxket-driven opportunities profit.Douglass for North, for example, famously downgraded theroleof theenttepreneurhisEconomic ofthe in Grovth United States, seeing no reason devote to timeor resources studying enttepreneurial to the function in American business. Enttepreneurs, argued, littlemorethanrespond he did to opportunities maximize to profits; their role was essentially passive: Eli if Whitneyhad not invented cottongin, someone wouldhave."The the else growing dilemma the South thatthedemand its ttaditional of was for export staples was no longerincreasing its heavycapitalinvestment and was in slaves... [I]nvention the cottongin canbe viewed a response the of as to dilemma rather thanasanindependent accidental development" [North,1961,

pp. 8, 52].

As the Cliometricians in sttength cameincreasingly grew and to dominate Economic the History Association, business historians gradually abandoned organization favor of a new association, Business that in the History Conference. Business The History Conference itsorigin a series had in of meetings, beginning Northwestern 1954, that broughttogether at in economic business and historians wererebelling, who onceagain, against the atheoretical of scholarship type promoted Gras.The groupmet twicein by 1954,oncein 1956,oncein 1958,andthenyearly thereafter; in 1971it and ttansformed itself into a full-fledged professional association with dues, officers, boardof trustees, a journal a and (albeit that onlypublished one a single issue yeax). per Although many itsoriginal of members economists, were

staxting the 1970s Conference in the increasingly provided intellectual an home

NEW ECONOMIC APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 61

for historians theCliometric fleeing Revolution. thepresent the 4 To day,

Business HistoryConference dominated trained is by historians, whereas the Economic History Associationcontrolled trained is by economists. In recent years, gulfhasif anything this grown widerasa result a shift of in historical fashions favorof cultural, opposed social economic, in as to or history. This shifthaseffectively redefined historical studies, thewordsof a in recent commentator, "as the investigation the contextually of situated production transmission meaning" hasinspired and of and historians takea to "linguistic turn"- thatis,to turnto thehermeneufics poststructural of literaxy theory ratherthanto theabstract models the social of sciences inspiration for andguidance [Toews, 1987, 882].Withinbusiness p. history, newemphasis the hasreinforced growing a waveof dissatisfaction theChandlerian with synthesis thathasdominated fieldof business the history the pasttwenty for years. This dissatisfaction stemmed partfromthe growing in conviction Chandler that had overemphasized efficiency the gains be derived to from the managerial coordinationof economic activitywithin large-scale enterprises [Pioreand Sabel, 1984; Scranton,1983; Scranton,1989]. But it also manifested itself as a rebellion against Chandler's narrowfocus the business on organization itself andthushasspurred scholars work on a variety previously to of .unexamined issues for example, culture corporations the wayin whichgender the of or constructs become embodied business in practice [Dellhelm, 1987;Kwolek-

Foiland, 1994].Although this broadening research of interests unquesis

tionably positive a development, downside beena tendency business its has for historians revertto the writingof largely to unrehted case studies a fashion in

reminiscent of Gras.

These developments also have moved fieldevenfurther the awayfrom economic theory thanbefore a result is particularly that unfortunate, because it is occurring a timewheneconomics moreto offerbusiness at has historians thaneverbefore. Abandoning convenient unrealistic the but assumptions of traditional neochssical theory in particular assumption all economic the that actors makedecisions thebasis perfect on of information economists have begun reconceptualize worldas a phcewhereinformation scarce, to the is imperfect, costly, and where "bounded the rationality" human of beings affects theireconomic decision making, whereinstitutions develop response in to problems imperfect of information, whereeconomic and processes have can

4AlfredD. Chandler, opposed Jr. the move to transform the Business History Conference a formalorganization into because did not want to abandon Economic he the

HistoryAssociation the Cliometdcians. pointof view did not prevail, to His however. [Videotape "Heritage of Session," consisting informal of remarks HaroldF. Williamson, by St.,Donald Kernmeter, AlfredD. Chandler, andWayne Jr., Broehl (reading comments from ThomasCochran), 34th AnnualMeetingof the Business HistoryConference, Atlanta, Georgia, 1988. would to thank We like William Hausman providing witha copy for us of

thistape. arealsobasing account therecollections LouisCain,communicated We this on of to NaomiLamoreaux ane-mail in message Jan.18;1996.] of

62 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

variant outcomesdepending participants' on past experiences and their

perceptions other's s ofeach actions.

The questions theheartof thisnewwork- howdo economic at actors knowwhat(they think)theyknowabouttheirworld,andhowdoes what(they think)theyknowaffecttheirbehavior areremarkably similar those to that inform the work of business historians interested addinga cultural in dimension theirwork.But,of course, theorists areparticipating to the who in thisintellectual movement interested, is theirwont,in developing are as formal economic models thatcapture newassumptions the aboutinformation in and exploring general the implications these of models. Theirworkis mathematical in character and,to the uninitiated observer, oftenappears bearlitfie or no to

connection actualcircumstances, to whethercurrentor historical. The aimsof

thesescholars thusverydifferent are from thoseof historians, are more who interested understanding in specifichistoricalphenomena. Indeed, the intellectual agendas the two disciplines of appear be so dissimilar it to that mightseem doubtful whether, theirown,practitioners evercome on could to appreciate, alone let learn anything, fromeach other's work. The purpose the series conferences haveorganized beento of of we has try to bridgethe gap- to showhow these recent theoretical developments in economics might be usedto write a new kind of business historythat simultaneously speaks the concerns the new generation business to of of historians piques interest economic and the of theorists. the remainder In of thisessay, pullexamples we frompapers presented ourmeetings from at and otherrecent work in orderto introduce newtheoryto the uninitiated the and to highlight potential its contribution business to history.

AsymmetricInformation Within the Firm

Traditionalneoclassical theory assumed that economic actorswere rationalbeingswho made optimizing decisions the basic of perfect on information foreknowledge. highlystylized and This view of humanbehavior wasa useful simplification enabled that economists deal to withcertain kinds of otherwise intractable problems, especially concerning markets, an effective in way [Friedman, 1953].As scholars haveincreasingly cometo realize, however, it wasinappropriate otherapplications for example, for understanding the behavior individual of firms. Traditional neoclassical theory treated firm as the a blackbox- asan equation-solving thatdetermined entity prices output and by setting marginal revenue equal marginal It wascompletely to cost. incapable of dealing with firmsas complex organizations composed people of with differing experiences goals. and Nor wasit capable explaining of how ftrms would respondstrategically the uncertain to environment which they in operated.

SForfurtherreferences introduction the economics imperfect and to of information, see RaftandTemin[1991].

NEW ECONOMIC

APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 63

The large-scale managerial organizations emerged the beginning that at of the twentieth century posed particular problems the neoclassical for theory of thefirm.The owners these of enterprises the stockholders, might, were who as in traditional theory,be conceptualized seeking maximizeprofits as to (thougheven here questions suchas the relevant time horizonstubbomly surface)..But stockholders typically not run the enterprises owned. did they This responsibility delegated managers werelikelyto havea very they to who differentset of priorities. example, For managers mightbe concerned with maximizing thei own compensation, guaranteeing themselves long-term job security, exploiting perksin orderto demonstrate conspicuously high their status, establishing or reputations that would enablethem to secure more important positions otherfLrrns. orderto guarantee, in In therefore, firms that operated accordance neodassical in with theory, stockholders to be ableto had impose theirownpriorities managers. thiscondition unlikely on But was to hold.Stockholders' powerwasoftenweakened the organizational by structure of thefirmandbythedispersion shares of among large varied a and population of individuals. addition, In stockholders typically verypoorinformation had aboutwhatmanagers wereactually doingandtherefore littleability check to theibehavior a regular on basis. Analogous problems neoclassical for theory appear all levels the at of large-scale enterprise. interests lowermanagers, example, be The of for may differentfrom thoseof managers the top of the organization, the at and interests workers of maydiverge fromthe concerns theisupervisors. of These difficulties knownin the recenttheoretical are literature prindpabagent as problems. principal's The responsibility spedfy is to goals theagent for and,in

orderto influencethe latter'saction,setthe rulesthat determine how much the

agent earn.Giventhese will rules, agent the chooses action an froma number of alternatives, whichaction mayor maynot be the outcome desired the by prLncipal. In the normalcase the one that is alsothe mostinteresting for historianstheinformation available thetwopatties therelationship to to is not the same. particular, principal not ableto observe In the is direcfiy the agent's action.Moreover, because theremaybe otherfactors that alsoaffect outcomes, prindpal notable infertheagent's the is to action any with degree of certainty theresults from obtained. a situation characterizedwhatis Such is by called "asymmetric information," because agent the knows moreabout or his her own actionsthan the principaldoes.To give some examples, the stockholders a firm aretheprincipals of whentheysetcompensation the for firm's CEO, thekagent. managers theftmarein turnprincipals The of when theydetermine working conditions payment forworkers, agents. and rules their The govemment as a prindpal acts whenit designs operates patent and a system induce to potential innovators, agents, discover products its to new and processes. each In case, principal(s) the cannot observe effortput forthby the the agent(s) onlyits result. And the resultmaybe the effectof chance or otherfactors wellastheagent's as effort.

64 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

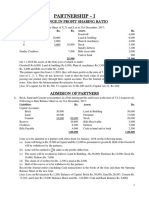

Economistshave fruitfully distinguished two broad classesof asymmetric informationproblems.In the first (calledhidden action or, sometimes, moral hazard),the agenttakes an unobservable action after contracting with the principal. For example, after negotiating employment contracts theirbosses, with workers haveto decide howmuchefforttheyare actually going expend theirjobs. to on Theymaydecide workless to thantheir employers expect theyjudge compensation if the insufficient if theythink or theirshirking go undetected. second of problems will The class (called hidden information in some or, cases, adverse selection) occurs whenthe agent has better information aboutsome relevant characteristic the principal. than For example, workers have moreknowledge theirownabilities do potential of than employers. Therefore, employer sets an who wages lowwillendupwithan too applicant pool disproportionately composed the poorersort of worker. of Similarly, thegovernment to create if fails secure property rights invention, in serious inventors bescared andonlycharlatans may away advance ideas. new The task faced theprincipal, by therefore, to design setof rules is a that will attractgood agentsto the activityand elicit their maximumeffort. Operating underconditions asymmetric of information, principal to the has forecast agents' the reactions the ruleshe or shedesigns. the end, to In moreover, principal notevenknowwhether rules the may the formulated were thebestones possible because outcomes notprovide do certain guidance. The

principal cannot know, example, a successful owed theagent's for if result to strong efforts wassimply matter good or a of luck[Arrow, 1985]. One setting whichtheseissues in ariseis the design employee of compensation systems. Because high-quality information aboutsubordinates is oftenexpensive gather, to superiors typically ways economizing seek of on monitoring costs. One technique reducing for costs that hasbeendiscussed extensivelytheliterature to structure in is compensation systems such way in a asto align subordinates' interests those theirsuperiors. example, with of For managers mightbe remunerated least partin shares stock orderto at in of in increasethe identity of interestsbetweenthemselves and the firm's shareholders. Similarly, firms may institute incentive schemes reward that individual workers according theirproductivity. Daniel to As Rafthas shown in "The Puzzling Profusionof Compensation Schemes the Interwar in Automobile Industry," technologyfttmemploys the a affects costs faces the it

in monitoring its workers and thus the attractiveness altemafive of compensation schemes [Raff, 1995]. For example, plans that rewarded

individual achievement madesense wherearfisanal modes production of

prevailed that is, whereindividual mechanics madesubstantial fractions of

cars. Firms used that more integrated methods, however, better using were off groupcompensation schemes, because did the company good to it no encourage individual be moreproductive theotherworkers the an to than on line. Finally,firms like Ford, which usedboth mass-production (interchangeable andassembly methods better paying wages. parts) line were off flat This particular technology madeit easier and cheaper monitor to workers' efforts because simplified tasks individuals to accomplish it the that had and

NEW ECONOMIC

APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 65

allowed machines set the paceof work. As a result,it was no longer to necessary useincentive to schemes a substitute information as for gathering. All thatwasnecessary to pay was workers wage made a that them wantto keep their jobs,and fire thosethat did not keepup. Raft shows that as mass production methods spread through industry, the firmsabandoned incentive plans favor straight-wage in of compensation schemes. Raff's article shed lightontheprincipal-agent literature showing by how thespecific character automobile of technology affected nature therules the of thatmanagers (principals) forworkers set (agents). wasalso contribution It a to thehistorical literature becauseexplained automobile it why workers during the interwar period werepaidin such very different ways, and perhaps more important, gaveevidence the slowdiffusion Ford'smass of of production methodsthroughthe industry. However,Raff's studyonly serves an as introduction the possibilities historical to for understanding the new that economic theoryopens Once one begins think aboutfirmsin the up. to context imperfect of information, wholehostof new questions a comes to mind. For example, although compensation schemes could be used to economize the needfor information on aboutworkers' efforts, managers still hadto keeprecords otheraspects theirbusiness of of dealings hadto be and ableto callup thatinformation needed. JoAnne as As Yates demonstrated in "Investing Information," development efficient in the of information storage and retrieval techniques not a trivialproblem largefro'ns the late was for in nineteenth century [Yates, 1991; Yates, 1989]. Yatesdetails series innovations thehandling information a of in of that revolutionized managers' ability to keep track of their business dealings. Among thesewere such familiar(to us) devices the file cabinet,the as typewriter, and carbonpaper.Previously, businesses records their kept of outgoing correspondence byusing presses make to impressionsletters of while the ink was still wet - difficult-to-read copiesthat were then bound in chronological intolarge order books. Incoming correspondence folded was and placed boxes, in again typically chronological in order.Such system record a of keeping madeit verydifficult firmsto access for information from the past. Managers oftenunable locate were to correspondence dealing with particular

transactions, and even when the information was found, the searchwas time

consuming labor intensive. and The innovations Yates detailssolvedthis problem enabling by firmsto copy outgoing correspondence efficient in an and readable way, and to storeboth incoming and outgoing letters together in clearly labeled files. Moreover, otherinnovations allowed firmsto makeuseof the new retrieval system internalmanagement. for Mimeograph machines meantthat managers couldduplicate sendmemos subordinates, and to who would now be able to storethe directives appropriate in files.In addition, printedformsenabled managers collect to information abouttheirinternal operations, whichcould data thenbe analyzed stored comparison and for with succeeding periods. But what informationshould firms gather to improve their performance? Margaret As Levenstein shown her studyof the Dow has in

66 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

Chemical Company, information fro'ns the that collected depended their on business strategy [Levenstein, Levenstein, 1991; forthcoming]. (likemost Dow firmsduring latenineteenth the century) initially employed standard mercantile accounts keeptrackof transactions suppliers customers to to with and and monitoremployees honesty. the firm began develop for As to newproducts andprocesses, however, typeof information this system proved increasingly inadequate, Dow experimented waysof measuring and with production costs andtechnical efficiency. moreproducts firm produced, The the however, the moredifficult werethe accounting problems. Whatthe fm'nreally needed was price-cost differentials net income and ftgures individual for products, but these, turnsout,werenot easy it measures develop to because the many of problems involved allocating burdens fixed in the of costs of shared and inputs

among firm'svarious a outputs. The problem with accounting developed such rules for purposes that is theyare artificial constructs which,if not usedextraordinarily carefully, can have perverse effects subordinates' on behavior. Whether theybe managers or workers, subordinates naturally will concentrate improving on along whatever

magnitude being is used evaluate performance, if theactions to their even they take are contrary the good of the enterprise a whole. For example, to as H. Thomas Johnson RobertS. Kaphn haveshown and that,asa result the of growing power finance of departments within large firms themid-twentieth in

century, becamecommonpractice firms to "roll back" their financial it for accounts usethemto measure and operational performance theplantlevelat a practice that,theyargue, suchdetrimental had consequences American for industry it mayexplain that muchaboutits declining competitivenessrecent in years [Johnson, Johnson Kaphn,1987]. 1991; and According Johnson to and Kaphn, in the first half of the century businesses a variety different used of types information some of financial but much not - to manage enterprise the internally. Beginning the 1950s, in however, businesses beganto use the financial accounting techniques for internal management purposes wereinitially that devised demonstrate to the

creditworthiness company theexternal of the to world- thatis,theybegan to usethese accounts a purpose originally for not intended. orderto generate In public financial statements, hadto distinguish frans between goods sold(the cost which anexpense of is deducted theincome on statement) goods and still on hand(anasset listed thebalance on sheet inventory) be ableto attach as and appropriate values each. to Thiswasa fairly straightforward problem direct for costs raw materials. it wasa muchmorecomplicated like But problem for indirect costs(overhead), the mostcommon and procedure to prorate was themoverthedirect hborhours expended each on product. Such procedure a wasfine for financial reporting purposes, whenthistypeof accounting but system was used internally monitor and rewardmanagers, created to it incentives hadhighly that pernicious consequences. example, For underthis system tracking the schemes usedwithin the firm for hbor and machinery typically reported directcostsper unit of output,but for indirectcosts, reporting schemes typically tracked percentage overhead the of covered or

NEW ECONOMIC

APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 67

earned units by produced. goal these The of reporting schemes to have was all recorded directlaboror machine hoursgo towardproduction unitsof of output thereby and absorb direct overhead and costs. Whenthishappened a manager regarded efficient. was as Under system, this therefore, managers were rewarded scheduling for workers machines longproduction - that and on runs is, there was an incentive not to devotetime to categories indirector of nonchargeable such changeoverssetups. problem, time as or The however, was thatunder thistypeof accounting procedure, did not matter it whether the output really was salable. Stoppinglineto correct production a a defect counted against efficiency thedepartment, managers anincentive keep the of so had to lines moving regardless quality. of Indeed, under these systems, hours spent on allowable rework wereoftenconsidered be efficiently to covered, workers so mightspend hours p'fiing products defects theywouldlaterspend up with that hours reworking. Clearly, behavior not efficient. theotherhand, this was On it waselicited theaccounting by system wasin place. that The spread thiskindof accounting of system during postwar was the era to a large extent function changing a of powerrelations withinlarge firmsasa resultof the diversification movement and the adoption decentralized, of multidivisional organizational structures. new "M-form"of organization The increased distance the between managers theoperating in divisions those and at thetopof theorganization. latter The nowoftenhadverylittlemanufacturing experience were generally and unfamiliar with the process-specific physical accounting measures hadpreviously used assess performance that been to the of individual plants. Trained rateof return in accounting business at schools anddetermined findsome of comparing performance producers to way the of making different very kinds goods far-flung of theorganization, of in parts they imposed newsystem theoperating the on divisions. Managers theoperating in units wouldhave preferred othermeasurement systems, theyhadlostthe but powerto maketheiropinions heard. As thisdiscussion accounting of suggests, managers located separate in parts a company haveverydifferent of may ideas about howthe enterprise should run.Bernard be Carlson generalized ideaby arguing fro'ns has this that should thought as collections interest be of of groups, eachwith its own "business technological mindset." balance power The of among these groups thendetermines the fn-m behave. how will Carlson developed ideain his this studyof the Thomson-Houston ElectricCompany [Carlson, 1995;Carlson, 1991].He showed that therewerethreepowerful groups withinthe firm: a marketing finance and grouporganized around Charles Coffinat the fmn's A. headquarters; a manufacturing ledbyEdwin group Wilbur Rice, at theLynn Jr. plant; andan invention group headed ElihuThomson worked of by that out the firm's model room. each these As of groups pursued ownfunctions, their they developed distinct mindsets affected that how eachthought finn the should operate. Theirideas about proper strategy oftencame conflict into with

each other, and these clashes had to be worked out before action could be

taken. Because noneof thegroups perfect had information foreknowledge, or the strategy fn-m the pursued cannot regarded the outcome anystrict be as of

68 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, ANDTEMIN

logicof the market, however successfulultimately it provedto be. Ratherthe strategy resulted fromthepolitical give-and-take timeof these over three major groups, pushing whatk thought in thebest each for was interests thefirm. of Inspired Carlsoh's by concept a business of technological mindset, we return the subject compensation to of systems, topic the withwhich began we thisdiscussion. argued theprofusion compensation Raft that of schemes the in interwar automobile industry resulted fromthedifferent technologies firms that in operation that timeemployed. at However, mayalsowishto askwhy, we during particular this period, firmsnotchanging basic their technologies would change their incentive plansat all. DanielNelsonprovides answer an by arguing thisexperimentation partof theethic industrial that was of engineering, a movement swept that through manufacturing the sector duringthe early twentieth century part of the coming consciousnessa newgeneration as to of of professional managers [Nelson, 1995]. Although, ksimtial in conception, the industrial engineering movement encompassed a muchbroader of ideas set than compensation schemes, consultants as competed with each other for clients,they found themselves underenormous pressure deliverquick to results. Incentiveschemes promised yield increases productivity to in in relatively short periods time,andsobecame focus theirefforts. of the of These fewexamples particular last in underscore consequences the that

followfromabandoning neoclassical the assumption perfect of information. Understandingfirm'sbehavior no longer a is simply matterof calculating a marginal revenue marginal and cost. Now the importance the particular of historical context to be recognized. understand decisions made, has To how are onehasto takeintoaccount technology the employed thefirm,thewayin by whichpoweris distributed withintheorganization, knowledge the structures at thedisposal different of groups within enterprise, goals aspirations the the and of these various economic actors, thewayin which and their concerns up link withbroad intellectual movements thelarger in society. But abandoning assumption perfect the of information doesnot mean abandoning economic theory. overview have presented The we just would not havebeenpossible without discipline questions the of derived fromtheory. Whatproblems imperfect does information for therelationship pose between principals agents? and How can principals restructure relationship the to economize information? on How do informational imperfections shape the decisions behavior actors and of withina firm?And, finally, how doesthe structure theenterprise of affect wayin which the people located different in parts theenterprise able make of theinformation possess? of are to use they Unlikethepursuit questions of derived fromthe standard neoclassical model, however, abilityto answer our thesequestions enhanced the use of is by techniques outside discipline economics. helps knowwhat from the of It to managers were thinking aboutin orderto understand what theywere just doing.

NEW ECONOMIC

APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 69

Asymmetric InformationBetween Finns Thusfarwehave focused theways which on in asymmetric imperfect or information affected internal the operations fro-ns. firmsalsofaced of But information problems when they confronted external their environment. we As will see, fro-ns dealt with theuncertainty surrounded in a number that them of

ways: xploited they whatever informational advantagespossessed, they altered

their business strategies pursue to activities entailed that lessuncertainty, created organizations either that economized information reduced on or the risks making of wrongdecisions, builtspecial and capabilities enabled that them(andnot theircompetitors) exploit to informational asymmetries. we As will alsosee,the bestway to understand thesebehaviors onceagainto is combine inquiry disciplined theneweconomic by theory withthetechniques of

historical scholarship.

Nowhereis the problem imperfect of information clearer more or insistentthan in the financialsector,where lendinginstitutions have to

scrutinize the creditworthiness of those who come to them for funds. In

theoretical terms, financial institutions function principals as whentheyprovide resources support activities theiragents to the of (borrowers). wasthecase As withmanagers employees, andotherfinancial and banks intermediaries cannot know everything would they wantto know about individuals firms the and they finance. Therefore, principals wantto design as they ways lending avoid of that moral hazardand adverse selection. firms, for example, If were not held accountable the fundstheyreceived, for theirmanagers mightsimply off run withthemoney. if banks Or charged highinterest thatnormal such rates firms could affordto borrow, not onlypoorrisks willing takegreat to chances would applyfor loans. The first case, whereborrowers badlyis an example act of moralhazard; second, the whereonly bad risksborrow,is an example of

adverse selection.

In relatively undeveloped economies, information aboutborrowers is scarce of uncertain and quality. such In economies bankers havea greatdeal

more information about the creditworthiness of borrowers who are dose to

themthantheydo aboutstrangers. NaomiLamoreaux argues thepractice that of banks lending large a proportion theirfunds insiders, of to common early in nineteenth-century England,made good economic New sense under these circumstances [Lamoreaux, 1991; Lamoreaux, 1994].The maindanger such of insiderlending wasthat excessive loansto thoseclosely connected with the banks' officers wouldendanger financial the health theinstitution, early of but New England bankers st_tong had incentives to lendtoomuch not money to themselves to their friends or andrelatives. Their positions the bankgave in themprivileged access loans to onlysolongastheirbankremained sound in condition. Moreover, an economy in where information scarce, was reputation

countedfor a lot. If a bank'sofficerswere to cause their institutionto fail, not

onlywouldtheylosetheirmainsource funds, the damage sucha of but that failure wouldcause theirreputations to would makeit difficult themto confor tinuein business. Giventhese pressures restraint, for Lamoreaux argues, insider

70 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

lending actually served useful a function thisinformation-poor in economy. Becausewas it common knowledge each that bank's portfolio consisted large in measure loans bankinsiders, because entrepreneurial of to and the activities of these insiders werereadily obsenrable, people whohadfunds invest a to had great dealmoreinformation about bankportfolios theyhadabout than other possible investments. could benefit They also from diversity theactivities the of in which these groups insiders of typically engaged. a result, As funds flowed freely theNewEngland into banking sector theearly in nineteenth century and from thereintoeconomic development moregenerally. As the economy matured, quality quantity information the and of that wasavailable bankers to improved, theproblems but associated lending with to strangers not completely did disappear. Lamoreaux As argues, whenbanks began lendmore theirfunds arms-length to of to borrowers, increasingly they restricted business short-term their to commercial lending. typeof lending This reduced by keeping risks borrowers a short on leash by confining bank's and a business thetypes loans to of about which information mostlikelyto be was available, the costwasthatbanks but effectively abandoned support their of economic development. Moreover, Kenneth as Snowden shown, has other types financial of institutions evenmoreserious faced information problems during period. example, thecase mortgage this For in of lending problems the

were so severe that it was difficult to mobilize funds from outside the

immediate areaand,as a result, interest ratedifferentials between capital rich andcapital poorareas werehuge[Snowden, 1995].Onlysomeone the spot on couldhave the necessary knowledge localreal estate of values and which borrowers werelikely be goodcredit to risks. Onlysomeone thespotcould on makesurethatproperty usedassecurity a debtdid not depreciate the for in hands theborrower. of Finally, onlysomeone the spotcould on takeoverand manage property theevent a default. the in of Because interest differentials rate made retums the frominterregional lending attractive thelatenineteenth so in andearlytwentieth century, lenders experimented a variety organizawith of tional arrangements example, use mortgage (for the of brokers local and agents) to reduce informational the asymmetries. thesearrangements But introduced newagency information and problems theirown,problems of which produced theboom-bust cycles aresofamiliar students theperiod. that to of Onlywhen the federal government stepped to provide in mortgage guarantees the after GreatDepression werethe informational problems overcome, allowing the mortgage market become national thefirsttime. to truly for Similar information problems plagued investment industrial in firms. For thisreason, during nineteenth the century individuals savings with rarely

bought equity manufacturing in enterprises, for a small except number wellof known localfawns whose stock traded theregional was on exchanges. Charles CalomLris argued in nations Germany, has that like where banks pursued set a of policies knownunderthe rubricof universal banking, these information problems werelargely resolved [Calomkis, 1995]. Banks tookequity positions in the firmsto whichtheylentfunds andalso placed directors the firms' on boards. thismanner, In theywereableto gainmoreinformation aboutthe

NEW ECONOMIC APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 71

fLrrns' internaloperations thanwas feasible individual for lenders. Banksthus served "delegated as monitors." Because they had both superior information about industrialfirms and also diversified portfolios,savers who were not willingto invest directly industry in couldput theirmoney banks in whichin turnwouldinvest industry them. in for As both Lamoreaux Calomiris and haveargued, the latenineteenth by

century most commercial banks theUnited in States wereunwilling perform to thisfunction. thereweresome But private bankers willingto takeit on. The bestknownwasJ.P.Morgan. Duringthe latenineteenth century Morgan had confined activities the New York Stock his on Exchange largely the finance to of railroads, during GreatMerger but the Movement 1895to 1904,hebegan of to underwrite creation giantindustrial the of consolidations. Typically, he wouldinvest the enterprise wellas underwrite andthenput oneor in as it, moreof his associates the boardso as to be betterableto monitor(and on influence) firm'sactivities. the Bradford Longhasattempted measure De to the economic benefits such participation Morgan[De Long,1991].He of a by foundthatfirmswith Morgan partners theirboards on earned higher profits and greater returns their stockholders otherlargeftrmsat the same for than time.The inference drawnis thatJ.P Morgan Company's & service a as delegated monitor reduced information asymmetries helped and insure the that

managersof these consolidations would act in the interests of their

stockholders.

Although problemof acquiring the information aboutthe external environmentparticularly for thebanking is clear sector, firms other in parts of the economy facedsimilar difficulties. example, orderto be ableto For in dispose theirgoods, of manufacturing needed firms accurate information about thepricing output and decisions theirrivals. of Thisneed became especially great once ftrms grew large relative themarket could to and actually prices, set instead having behave theprice-takers the standard of to like of neoclassical model. Moreover, firms' as cost structures became increasingly dominated by fixed capital expenses, temptation to tryto increase market the rose their share byundercutting prices. a situation perfect rivals' In of information, would firms quickly learnnot to giveway to temptation. Their pricecutswouldbe immediately detected competitors copied; by and market shares wouldremain as theywere;and everyone wouldendup selling theirgoods lessthan for before.In a situation whereinformation imperfect, was however, was it possible a firmto keepa price secret for cut fromits rivals longenough substantially to increase sales. its During late the nineteenth early and twentieth centuries, example, for there weremany newindustries whichftrms not in had yet had time to establish their positions and take the mettle of their competitors. addition, dramatic anddowns the business In the ups of cycle made difficult firms tellwhether drop sales caused a fallin it for to a in was by demand generally by theprice or cutting a rival.Undersuch of circumstances, thetemptation undercut to rivals' prices seems have to been verystrong, and fLrrns turned various to kinds collusive of organizationstry to halt the to downward-spiraling competition price [Lamoreaux, 1985].

72 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

Under similar circumstances Europeanfirms organizedcartelsto control output fix prices remunerative and at levels. theUnited In States firms alsoturned cartels, withmuchless to but success, ultimately and turned instead to horizontal mergers. orderto explain In why cartels workedfor Europeans and not Americans, scholars havefocused legaldifferences. example, on For Tony Freyertraced evolution legaltraditions the UnitedStates the of in and Britain to showwhy the organizational choices made by large firms were different thetwonations. in Whereas Britain in cartels evolved frombeing legal butunenforceable contracts enforceable to ones, theUnitedStates were in they not onlyunenforceable the endof the nineteenth by century illegal well but as

[Freyer, 1992,1995].

Mergersdid not usually succeed eliminating in price competition, however. The highprices consolidations the charged the years in immediately following their formation stimulated host of entry by new firms.The a consolidations gradually lost market share,and their industries typically reverted an oligopolistic to marketstructure. With cartels illegal the United in States, firmshadto develop alternative of coping ways withpricecompetition. Onedevice grew popularity that in during 1920s theopenpriceassocthe was iation,whose mainpurpose the collection dissemination informawas and of tion about prices output. and The ideawasthatif firmshadbetter information aboutthese magnitudes, cutting price wouldbe easier detect, to and so the incentive increase to marketshare undercutting by competitors' prices would be greatly reduced. However,asDavid Genesore Wallace and Mullin foundin their study one suchassociation, Sugar of the Institute, firmswereinitially reluctant makethis kind of information to available competitors the to and Institutehad to learnhow to guarantee credibly that data on individual producers wouldbe handled carefully confidentially thatcompetitors and so wouldnot gainanyadvantage theexchange from [Genesore Mullin,forthand coming]. Even so,fro-ns werereluctant share to certain kindsof information, for example detailed reports theirsales. the root of the problem of At were information asymmetries withinthe Association itself.Firmsthatwerelarge relative themarket to knew moreabout whattheircompetitors doing were than firmsthatweresmall, they and werenotwilling giveupthatadvantage. to As thisdiscussion theSugar of Institute suggested, candiffer has firms

in their command information theexternal of about environment.thesugar In

case, differences primarily a result variations size: the arose as of in large firms hadmoreinformation about market activity thansmall. in othercases, But the information firmsobtain maybe a function the extent whichtheyinvest of to in collecting NaomiLamoreaux Kenneth it. and Sokoloff argue, instance, for thatanactive market patented for inventions developed thecourse the over of nineteenth century. the"high-tech" of theeconomy particular, In parts in firms seeking stay thetechnological to on cutting invested staffs employees edge in of whose mainfunction to acquire was knowledge aboutinventions developed outside firm andto assess the whether company the should purchase them [Lamoreaux Sokoloff, and forthcoming]. DavidMowery also has pointed out theimportance such of capabilities, arguing even that when large firms builtup

NEW ECONOMIC

APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 73

theirowninternal R&D departments, monitoring technological developments in the external environment remained important an aspect theiractivities. of According Moweqr, to tighter antitrust enforcement mid-century by madeit difficult large for firms continue purchase to to externally generated inventions, and so theydismantled some theirinvesmaents such of in capabilities, the to detriment, Moweqr argues, the econoroy's of overall paceof technological development [Moweqr, 1995]. Because invesmaentscapabilities thissortweresoexpensive, in of some fransturned organizational to substitutes. example, For many small firmsused patent solicitors keep abreast inventions to of relativeto their interests. Although the main purpose theselegalrepresentatives initiallyto of was shepherd applications through PatentOfficeand to defend the patentees in interference and infringement proceedings, they developed over time specialized technical expertise ftrrns that couldtap to keepup with developmentsin the restof the economy. Steven Usselman describes another substitute investing thecapability assess for in to externally generated technologies: patent pools[Usselman, forthcoming]. These organizations employed were by largefirmsin industries wheretherewasakeady largeamount interfirm a of cooperation. Essentially these what pools wasenable did firmsto collude in acquiring new technology. jointlypurchasing crosslicensing By and new inventions, eliminated riskthata competitor they the would monopolizevital a technology. also They keptthecost acquiring of inventions low. Such substitutes worked fairly well so long as most important technological developments occurred the externalenvironment. in Once internalR&D grew in significance, however,ftrrnsthat did not investin building these up capabilities found often themselvesa competitive at disadvantage. Moreover, once technological change moved inside ftrrns, character its changed important in ways. Usselman suggested, As has it became focused less on the acquisition patents of and more on the overall goalof increasing efficiency through systemization standardization. and Improvements this of sorttypically involved great a dealof firm-specific knowledge. Unlikepatents, therefore, could betraded themarket. they not on

Dynamic Consequences

Onestrand therecent of theoretical literature extended pointto has this argue that particular waysof doingthings become imbedded the routines in and organizational cultureof an enterprise can themselves and becomean important source competitive of advantage [Nelson Winter,1982]. and They become established the first placebecause in they work. An enterprise innovates a particular achieves results, thenattempts build in way, good and to on its success expanding sameor similar by the practices other areas. to Because routines result the that typically depend considerable on firm-specific knowledge attributes, and competitors themdifficult copy. find to Successful imitation involves replicating onlya product production not or process also but the organizational resources generated sustained innovation. is that and the It

74 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

often extremely difficultfor otherfirmsevento leam the outward details of whatis required, aloneunderstand let whatunderlies them.This strand the of literature thuslinksthe concept asymmetric of information with historians' methods understandinganexplicit of in way.Firms successtiff thelong are over run because, buildingon pastchoices by and experiences, are able to they exploit theirownprivate highly and specialized knowledge. Although firm-specific organizational routinescan be a sourceof competitive advantage, canalsomakeit difficultfor firmsto respond they to competitive challenges moveinto newtechnologies. pointcanbe seen or The dramatically comparing by Ford'sexperience aircraftmanufacture in with Boeing's during WorldWarII [Mishina, forthcoming]. attempted apply Ford to its automobile technology aircraftproduction, to transferring massits production assembly-line techniques themanufacture airplanes. these to of But

methods meant space Ford's that in plants rigidly was partiti9ned assembly by

linesanddedicated particular to uses, structure madeit difficultfor Ford a that to increase outputrapidly response the skyrocketing its in to militarydemand for planes. Kazuhiro As Mishina shows, Boeing's moreflexible of group use assembly techniques, whichharkedbackto an earlierstage automobile of production, permitted muchgreater outputgrowthover the war period.As Boeing's managers facedinsistent demands from the militaryfor additional planes, wereableto rearrange plants asto make they their so moreefficient use of the available space and permit a greater throughput. The results were dramatic: thespace fouryears, direct in of the labortimeit tookto makea B-17 bomber declined from71worker years a mereeight. to Ford's morerigidsystem proved disastrous, thefirmemerged and from theGreatDepression WorldWar II nearly and bankrupt. rescue failing To the enterprise, new CEO, HenryFord II, lureda wholeteamof executives the

away from GeneralMotors.The GM peopleimmediately to work set reinventing along lines General Ford the of Motors thatis, theysetabout replacing Ford's highly centralized organizational structure the decentralwith

izedmultidivisional formusedat GM. As DavidHounshell shown, GM has the peopleseemed be succeeding restructuring to in Ford [Hounshell, forth-

coming]. a keyvotein late1949, example, company's executives In for the top approved planto buildtwo newengine a plants wouldprovide firm that the withbadly needed production capacity at thesame and timefurther process the

of decentralization. Less than a month later, however, the decision was

reversed. Akhough thereareno records reveal that whatactually happened at thatsubsequent meeting, of theexplanation theshiftappears be the part for to difficulty the project of kself.Ford'scentralized organizational structure was embodied physical in capkal the form of the hugeRiverRouge in plantin Detroit.As the executives confronted costs the involved dismantling in the Rouge asto transform so Ford's organizational structure along GM lines, they seem havebacked to away. Rather thancopy GM, whatForddidinstead was developa new business strategy that madeeffective use of its own sunk investments plantand in particular in waysof doingthings, strategy a that

provedprofitable thenextperiod. in

NEW ECONOMIC

APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 75

Whenfirmsfailto exploit capacities hadbuiltup overtheyears, the they

the resttits can be momentous. The case of Sears offers an instructive lesson.

As Daniel Raff and Peter Temin have argued, Searsfacedtwo important turning points during history thefirstin themid-1920s, thesecond its and in the late1970s[RaffandTemin,forthcoming]. Duringthe firstepisode, Julius Rosenwald hiredGeneral Robert Woodto addretailstores Sears's to catalogue business. expansion This madegooduseof the expertise goodwill that and Sears already had accumulated enabled fm'n holdontoitsclientele and the to as families became moreurban, workmoved from agriculture industry, into and people increasingly traveled car.In the second by episode, Sears's executives debated firm's the future path.Onegroup wanted follow to whatit thought to be General Wood'sexample addnewdimensions Sears's and to retailactivities; another group wanted revitalize company's to the stores. firstgroupwon, The andSears expanded financial into services. thehoped-for But synergy between thesale goods, theonehand, financial of on and instruments, theother, on did not materialize. executives' The misperception the fm'n's of special capabilities

cost firmmany the years itscontest stores Wal-Mart theGap, in with like and stores which increased market their share using information by new technology to lower prices improve and responsiveness to consumer demand. Likefirms, nations make can investmentsspecific of organizing in ways economic activity whatwe callinstitutionsthatgivethemeconomic advantages other over nations. Alfred Chandler, hasargued thelarge-scale D. Jr., that enterprises emerged theUnited that in States during early the twentieth century (in largemeasure, Freyertellsus, because as cartels wereillegalhere)were responsible theextraordinary for performance theU.S.economy of [Chandler,

1977;Chandler, 1990].But LeslieHannahhas shownthat this view will not

withstand empirical scrutiny. tracks performance thelargest He the of firms in theUnited States, Great Britain, Germany thecourse thetwentieth and over of century, finds and thatlarge firms general U.S.firms particular in and in have not done especially well [Hannah, forthcoming]. Chandler assumed that managerial control vertically of integrated enterprises provided coordination a mechanism superior anythatcouldoperate to through market, this the but assumption alsobeenincreasingly has calledinto question. example, For Michael Enright shown small has that vertically disintegrated geographically but concentrated candevelop firms coordination mechanisms canbe superior that to managerial hierarchies theirflexibility respond changes consumer in to to in demand. Similar arguments theadvantages about of clusters small of vertically disintegrated over firms large managerially directed enterprises been have made byscholars diverse Michael as as Piore Charles and Sabel Philip and Scranton [Piore Sabel, and 1984; Scranton, Scranton, 1983; 1989]. If large-scale enterprises not account theextraordinary do for success of the U.S. economy duringthe earlytwentieth century, what does? Hannah argues that the explanation long-run for national differences economic in performance reside must either thenon-industrial in sectors theeconomy of or in the achievements smallfirms.Rising the challenge thiskind of of to that question poses, GavinWrighthasattempted elucidate particular to the "social

76 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN

capabilities" allowed United that the States move to intoa position world of economic leadership 1890[Wright, by forthcoming; DavidandWright,1992;

Abramovitz David,1996]. and Wrightfocuses thenetworks people on of that made possible transfer technological the of knowledge throughout nation. the During early the nineteenth century type communication facilitated this of was bythehighgeographic mobility labor, of particularly movement skilled the of mechanics a great of technological with deal know-how. Overthecourse the of

century, however networks these became formal technological more as change increasingly became workof engineers college the with training budding and professional identities. these As engineers organized themselves national into societies devoted the promotion theirfields, to of theyspread theirbrandof specialized knowledge like-minded to people other in parts thecountry. of Perhaps mostimportant these the of networks centered themining on industry. One common explanation the U.S. economy's for extraordinary performance the earlytwentieth by century wasits abundant material raw resources, Wright shown thenation's but has that share resource of production duringthis periodgreatly exceeded whatwe now knowto be its share of reserves. Whataccounted thesuperior performance, argues, not for U.S. he was resources se,but thecapacity exploit per to themthatthenation hadacquired

through networkof miningengineers. important its The lesson takeaway to fromthisexample, then,is thatnations firms like havebusiness histories. That is, we canunderstand their success studying special by the organizational and institutional arrangements developed exploit they to information asymmetries.

Conclusion

The studies havesummarized explore widevariety topics we here a of in business history,rangingfrom firms' efforts to improve their internal operations, the waysin whichorganizations mediate to can relations among individual enterprises, the wealthof nations. to Manyof these studies, such as Levenstein's work on accounting Dow, Genesore Mnllin'sanalysis at and of datacollection theSugar by Institute, Raft andTemin's and narrative Sears's of response changing to markets, narrowly are focused studies. in sharp case Yet,

contrast to the case studies that characterized the Grasian tradition of business

history,theseworks contribute a coherent to view of Americaneconomic development organizational and change. The sources this coherence fundamentally of are different, however, from thosethat underpinned Chandlerian the synthesis. latterhad at its The hearta deterministic of technological view change, unidirectional a modelof organizational evolution, a focus and that excluded broadrange topics a of from consideration. coherence underpins diverse of studies The that the set summarized is of a verydifferent here type,for it derives froma common less setof answers thanfrom a common of questions. of the authors set All take theimperfect nature information theirstarting of as point,andall canbe seen asilluminating ways which condition the in this plays in economic This out life. common preoccupation leadsto a second then source coherence the of -

NEW ECONOMIC APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 77

recognition there a structural behind these that is unity all various topics. The information problems firmsfacein theirinternal that operations not so are different fromthose theyface dealing theexternal that in with environment or fromthose faced firmsandothereconomic by actors whentheyinteract with oneanother. Further, solutions the adopted response these in to information problems typically havemanyfeatures common, oftenresultin the in and creation capabilities, of whether the fLrm, at organization, economy-wide or level, have that long-term salience. Fruitfulexploration this underlying of coherence depends first and foremost upongentfine interaction between economists business and historians. These two groups scholars different of do things. Business historians are primarily interested understanding in changes 6mein the behavior over and structure particular of economic organizations. Economists primarily are concerned building with general models economic of relationships with and exploring implications themodels build. the of they Despke their verydifferent interests, however, two groups scholars the of havemuchto gainfrom an exchange ideas. we havealready of As suggested, business historians turn can to economic theory bothfor useful ideas for thelighta coherent and perspectivesheds anotherwise on untidy past. theother On hand, business history can offereconomists useful correctives provocative and examples will inspire that themto givetheirmodels heightened realism greater and practical significance. It is important be absolutely about kindof interdisciplinary to clear the

dialogue are advocating we here. We are not callingfor a return to the hierarchical conception scholarship Gayattempted impose Gras of that to on during 1930s we do not see the business historians research as assistants for economists engage a higher who in levelof thinking. Although hopethata we byproduct thisdialogue be bettermodeling economists, main of will by our

concern is that the work of individual business historians redound to the credit

of thefieldof business history a whole. as The realbenefit recent of theoretical developments economics thattheyenable in is business historians recognize to the essential thatunderlies great unity a number the problems which of with theyareconcerned. a result,studies one topiccanresonate As on with studies on others, strengthening alland,in turn,thefieldasa whole. them

References

Abramovitz,M., and P.A. David, "Convergence Deferred Catch-up: and Productivity Leadership theWaning American and of Exceptionalism," Landau, Taylor, in R. T. and G. Wright, eds., Mosaic Economic (Stanford, The of Growth 1996), 21-62. Arrow,K.J.,"The Economics Agency," J.W.PrattandR. Zeckhauser, Prindpals of in eds., andAgents (Boston, 1985),37-51. Calomiris, C.W., "The Costsof Rejecting UniversalBanking: AmericanFinancein the GermanMirror, 1870-1914," Lamoreaux Raff, eds.,Cooranation Infirmat?on, in and and

257-315.

Carlson, W.B., "The Coordination Business of Organization Technological and Innovation within the Firm:A CaseStudyof the Thomson-Houston ElectricCompany the in 1880s," Lamoreaux Raff, eds.,Cooradiation InJbrmation, in and and 55-94.

78 / LAMOREAUX, RAFF, AND TEMIN , Innovationa Sodal as Process: Thomson theRise General Ehu and of Elec#ic, 1870-1900 (NewYork, 1991). Chandler, A.D., Jr., Scale Scope: Dynamics Industrial and The of Capitalsin (Cambridge, MA, 199o). , The Visible Hand:TheManagerial RevolutionAmerican in Business (Cambridge, MA, 1977). Cole,A.H., "Economic Historyin the United States: Formative Yearsof a Discipline," Journal Economic of History, (1968), 28 556-89.

David,P.A.,andG..Wright, "Resource Abundance American and Economic Leadership," Stanford University Center Economic for Policy Research Publication 267(1992). No. DellheLm, "The Creation a Company C., of Culture: Cadburys, 1861-1931," American

Historical Rev/ev, (1987),13-44. 92 De Long, J.B., "Did J.P. Morgan'sMen Add Value?An Economist's Perspective on Financial Capitalism," Temin, Inside Business in ed., the Enterprise, 205-36. Enright, M.J.,"Organization Coordination Geographically and in Concentrated Industries," in Lamoreaux Raff,eds., and Cooranation andlnfirmation, 103-43. Freyer, Regulating Business: T., Big Antitrust Great in Bn'tain America, and 1880-1990 (Cambridge,

1992).

--,

"LegalRestraints EconomicCoordination: on Antitrustin Great Britain and America, 1880-1920," Lamomaux Raft,eds., in and CoorSnation andlnrmation, 183-202. Friedman, "The Methodology Positive M., of Economics," Essays Positim in in Economics (Chicago, 1953), 3-43. Galambos, "Parsonian L., Sociology Post-Progressive and History," SodalSdence.Quarter, 50

(1969),25-45.

Genesove, and W.P. Mullin, "The Sugar D., Institute Learnsto Organize Information Exchange," Lamoreaux, andTemin,eds., in Raff, Learning Doing y (forthcoming).

Hannah,L., "Marshall's 'Trees'and the Global 'Forest':Were 'Giant Redwoods' Different?"

in Lamoreaux, andTemin, Raft, eds., LearningDoing y (forthcoming). Heaton, "The EarlyHistory theEconomic H., of History Association," Journal Economic of History, (1941), 1 Supplement, 107-9. --, A ScholarAction: in Edmin Gay F. (Cambridge, 1952). MA, , "Twenty-Five Years of the EconomicHistory Association: Reflective A Evaluation," JournalEconomic of History, (1965), 25 465-79. Hounshell, D.A., "Assets, Organizations, Strategies, Traditions: and Organizational

Capabilities ConstraintstheRemaking FordMotorCompany, and in of 1946-1962," in

Lamoreaux, andTemin,eds., Raff, LearningDoing. 4Y Johnson, H.T., "Managing Remote by Control: Recent Management Accounting Practice in

Historical Perspective," in Temin, Inside Business ed., the Enterprise, 41-66. , andR.S.Kaplan, Relevance TheRise Fall ofManagement Lost.. and ,4ccounting (Boston,

1987).

Kwolek-Folland, Engendering A., Business.' andIV/omen theCorporate 1870-1930 Men in Office, (Baltimore, 1994). Lamoreaux, N.R., "Economic Historyand the Cliometric Revolution," A. Molho and in G. Wood, eds., Imagined Histories: American Historians the (Princeton, and Past forthcoming). , The Great Merger Movement inAmerican Business, 1895-1904 (NewYork, 1985). , "Information Problems and Banks'Spedalization Short-Term in Commercial Lending," Temin, Inside Business in ed., the Enterprise, 161-95. , Insider Lenang: Banks, Personal Connections, and Economic Development in Indus#ial New England (NewYork,1994). , and D.M.G. Raff, eds., Cooranation Inrmation: and Historical PerOectives on the Orgam'ation ofEnterprise (Chicago, 1995). , D.M.G. Raff,andP. Temin,eds., Learning Doing Markets, 4Y in Firms, Nations, and

forthcoming.

NEW ECONOMIC APPROACHES TO BUSINESS HISTORY / 79

--,

and K.L. Sokoloff,"Firms,Inventors, and the Market for Technology: U.S. Manufacturing the LateNineteenth EarlyTwentieth in and Centuries," Lamoreaux, in Raft,andTernin, eds., Learning Doing. y Levenstein, Accountingr M., Growth: Competition, Inrmation Systems, the and Creationthe of Large Co&orazion (Stanford, forthcoming). --, "TheUseof CostMeasures: Dow Chemical The Company, 1890-1914," Ternin, in ed.,Inside Business the Ente&rise, 71-112. Mishina, "Learning New Experiences: K., by Revisiting Flying the Fortress Learning Curve," in Lamoreaux, andTemin,eds., Raff, Learning Doing. y Mowery,D.C., "The Boundaries the U.S. Finn in R&D," in Lamoreaux Raff, eds., of and Cooranation lnrmation, and 147-182. Nelson, "Industrial D., Engineering theIndustrial and Enterprise," Lamoreaux Raff, in and eds., CooranationInrmazion, and 35-50.

Nelson, R.R.,andS.G.Winter, Evolutionary ofEconomic An Theory Change (Cambridge, MA,

1982).

North, D.C., TheEconomic Grovth theUnited of States, 1790-1860 (Englewood Cliffs,N.J.,

1961).

Piore, M.J.,andC.F.Sabel, SecondlndustialDivide The (NewYork,1984). Raff, D.M.G., "The Puzzling Profusion Compensation of Schemes the Interwar in Automobile Industry," Lamoreaux Raff,eds., in and Cooranation andlnfortaation, 13-33. --, and P. Temin, "Business Historyand RecentEconomic Theory:Imperfect Information, Incentives, theInternal and Organization Fims," Temin, Inside of in ed., the Business Ente&rise, 7-35. --, and P. Temin, "SearsRoebuckin the TwentiethCentury:Competition, Complementarities, the Problem Wasting and of Assets," Lamoreaux, in Raff, and Temin,eds., Learning Doing. y Sass, S.A., Entreprenemial Historians and History.' LeadershOo Razionah' and in American Economic Histoiograpy, 1940-1960 (NewYork,1986). Schumpeter, TheTheory Economic J.A. of Development.' An Inquiry Profits, into Capital, Creat, Interest, the and Business (Cambridge, 1934). Cycle MA, Scranton, Figured P., Tapestry.' Production, Markets, Pover Philadehia and in Textiles, !885-!94 !

(New York, 1989).

, Propietary Capitah)m: Textile The Manufacture at Philadehia, !800-!885(NewYork,

1983).

Snowden, K.A., "The Evolution Interregional of Mortgage Lending Channels, 1870-1940: The Life Insurance-Mortgage Company Connection," Lamoreaux Raff, eds., in and

Cooranation Inrmation, and 209-247.

Teece, D.J.,"TheDynamics Industrial of Capitalism, PerspectivesAlfredChandler's on Scale and Scope," JournalEconomic of [a'terature,(1993), 31 199-225. Temin,P., ed.,Inside Business the Enterpffse: Histoffcal Perqectives Useof Inrtaaln onthe

(Chicago, 1991).

Toews, "Intellectual J.E., History theLinguistic TheAutonomy Meaning after Turn: of and theIrreducibility Experience," of American Histoffcal Reviev,(1987), 92 879-907.

Usselman, "Intemalization Discovery American S., of by Railroads," Lamoreaux, in Raff, andTemin, eds., LearningDoing. y

Williamson, O.E., "TheModern Corporation: Origins, Evolution, Attributes," Journal f

Economic L?erature,(1981),1537-68. 19

Wright, "Cana NationLearn? G., American Technology a Network as Phenomenon," in Lamoreaux, andTemin, Raff, eds., Learning Doing. y Yates, Control J., Through Communication.. ofSystemAmerica The Ia)e in Management (Baltimore,

1989).

, "Investing Information: in Supply Demand the Use of Information and in in American Finns, 1850-1920," Temin, Inside Business in ed., the Ente&rise, 117-54.

You might also like

- Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and CareersFrom EverandGetting a Job: A Study of Contacts and CareersRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Business History and Management StudiesDocument30 pagesBusiness History and Management StudiesKrista SindacNo ratings yet

- Beyond the Market: The Social Foundations of Economic EfficiencyFrom EverandBeyond the Market: The Social Foundations of Economic EfficiencyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Working-Class Formation: Ninteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United StatesFrom EverandWorking-Class Formation: Ninteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United StatesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Return of Economic History?Document10 pagesThe Return of Economic History?María Fernanda JustinianoNo ratings yet

- Business HistoryDocument3 pagesBusiness HistoryJoyce DometitaNo ratings yet

- Tyler GoodspeedCapitalism and The Historians FinalDocument22 pagesTyler GoodspeedCapitalism and The Historians FinalpgandzNo ratings yet

- A Science and Its History: Chapter 1Document14 pagesA Science and Its History: Chapter 1dfarias1989No ratings yet

- History of Labour 2 - Commons PDFDocument662 pagesHistory of Labour 2 - Commons PDFsppaganoNo ratings yet

- Falcone e Osborne 2005Document8 pagesFalcone e Osborne 2005Tamires MariaNo ratings yet

- Structure and Change Douglass NorthDocument17 pagesStructure and Change Douglass NorthDiego Mauricio Diaz VelásquezNo ratings yet

- Galambos - Is This A Decisive Moment For The History of Business, Economic History, and The History of Capitalism (2014)Document19 pagesGalambos - Is This A Decisive Moment For The History of Business, Economic History, and The History of Capitalism (2014)capeluvoladoraNo ratings yet

- Association For Evolutionary Economics Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of Economic IssuesDocument40 pagesAssociation For Evolutionary Economics Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of Economic IssuesEdward KarimNo ratings yet

- Structural Economics: Measuring Change in Technology, Lifestyles, and the EnvironmentFrom EverandStructural Economics: Measuring Change in Technology, Lifestyles, and the EnvironmentNo ratings yet

- The Old New Social History and The New Old Social History (Tilly C., 1984)Document45 pagesThe Old New Social History and The New Old Social History (Tilly C., 1984)Diego QuartulliNo ratings yet

- Strange CareerDocument22 pagesStrange Careervivek.vasanNo ratings yet

- Hist 1Document115 pagesHist 1Spin FotonioNo ratings yet

- Ontology and Economic Thought HistoryDocument15 pagesOntology and Economic Thought HistoryeconstudentNo ratings yet

- International Business History JonesDocument26 pagesInternational Business History JonesisanajiNo ratings yet

- D C. N N - M I D: Ouglass Orth and ON Arxist Nstitutional EterminismDocument37 pagesD C. N N - M I D: Ouglass Orth and ON Arxist Nstitutional Eterminismelmin_ibrahimovNo ratings yet

- History and Entrepreneurship PDFDocument38 pagesHistory and Entrepreneurship PDFDel WNo ratings yet

- Kocka - History and The Social SciencesDocument21 pagesKocka - History and The Social Sciencesi_mazzolaNo ratings yet