Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Accidental Napalm Attack and Hegemonic Visions of America - S War in Vietnam

Uploaded by

dion82Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Accidental Napalm Attack and Hegemonic Visions of America - S War in Vietnam

Uploaded by

dion82Copyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] On: 02 April 2012, At: 17:40 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Critical Studies in Media Communication

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcsm20

Accidental Napalm Attack and Hegemonic Visions of America's War in Vietnam

Guy Westwell Available online: 28 Jun 2011

To cite this article: Guy Westwell (2011): Accidental Napalm Attack and Hegemonic Visions of America's War in Vietnam, Critical Studies in Media Communication, 28:5, 407-423 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2011.577790

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Critical Studies in Media Communication Vol. 28, No. 5, December 2011, pp. 407423

Accidental Napalm Attack and Hegemonic Visions of Americas War in Vietnam

Guy Westwell

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

Through a close examination of the initial dissemination and subsequent reproduction of the iconic Vietnam war photograph, Accidental Napalm Attack, this article indicates how hegemonic cultural/ideological processes have set the parameters for the circulation and consumption of this photograph, enabling this seemingly difficult and challenging image to be brought into line with relatively sympathetic reporting of the war in the early 1970s and to be appropriated by hegemonic revisionist accounts in the 1980s and 1990s. A key aim here is to offer something of a corrective to those accounts that state that upon initial publication the image had a powerful, almost traumatic, impact on the American public and that this impact was subsequently elided by the cultural/ideological work of revision and forgetting. This article argues that the initial shock potential of the photograph must not be exaggerated nor mythologized at the expense of a full acknowledgment of the photographs centrality to the larger ideological/cultural framing of the event it depicts, a framing that was from the outset limited and limiting in nature. Properly historicized in this way we are reminded that, even though difficult and challenging iconic images such as Accidental Napalm Attack may display the potential to foster a more detailed and critical apprehension of wars costs, they more often than not operate hegemonically to screen out wars horror. Keywords: photography; Vietnam war; Cultural memory; hegemony; kim phuc Introduction On June 8 1972, representatives of Independent Television News (ITN), the Associated Press (AP), and the National Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) positioned themselves on the outskirts of Trang Bang, a small hamlet in South Vietnam about

Dr Guy Westwell is a lecturer in Film Studies at Queen Mary, University of London and author of War Cinema Hollywood on the Front Line (London: Wallflower Press, 2006). Correspondence to: Queen Mary, University of London, Department of Languages, Linguistics and Film, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, UK. Email: g.r.westwell@qmul.ac.uk

ISSN 1529-5036 (print)/ISSN 1479-5809 (online) # 2011 National Communication Association http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2011.577790

408

G. Westwell

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

halfway between Saigon and the Cambodian border. A battle was taking place between the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) and the Viet Cong (NLF). As the news teams watched, South Vietnamese fighter planes flew overhead and dropped napalm canisters that missed the NLF positions and exploded above a road on the outskirts of the hamlet. A few moments later a group of adults and children, some badly burnt, appeared through the oily smoke of the napalm explosion. As they ran, AP photographer, Hyung Cong Nick Ut, stepped into their path and took a photograph that would become one of the best known of the late twentieth century. In this article I examine this photograph, titled Accidental Napalm Attack, via a careful historical and contextual analysis of its initial publication and subsequent reproduction in follow up news reports, a television documentary, a television feature film, and a magazine feature article.1 I begin by describing the ideological and institutional process of gatekeeping, whereby editors at AP, NBC, and The New York Times worked on the photograph prior to publication in ways that significantly shaped its meaning. I then track how the photograph was reproduced in a number of different contexts in ways that were consonant with its initial inception. As I present my findings I also challenge the widely held assumption that on its first publication the photograph was somehow laden with anti-war value*that it, in effect, shocked the U.S. public out of their complacency with regard to the war in Vietnam only to be later tamed by revisionist media and cultural practices (Hariman & Lucaites, 2007; Sturken, 1997). In the final part of the article I argue that a historical and contextual approach should be the default starting position for the analysis of iconic images such as Accidental Napalm Attack and that communications scholars must adopt suitably skeptical and critical reading strategies to ensure that the tendency to overstate war photographys traumatic and shocking affect is resisted. Gatekeeping at the Associated Press and The New York Times Newsgathering in Vietnam in the early 1970s was big business, involving a multimillion dollar annual outlay and strong competition between different news agencies, newspapers, and television companies (Braestrup, 1994, pp. 910). Any understanding of the inception of Accidental Napalm Attack must be grounded in the work of these news agencies as they selected and deselected images in response to the demands of a competitive news market. To shed light on this (often hidden) work of image production, I offer below a reconstruction of the likely conditions that shaped the photograph from its exposure in Uts Leica M2 camera through to its dissemination in the U.S. public sphere. Before doing this, it is worth nothing that, in critical accounts and histories of the photograph, this process of selection and de-selection is usually sidelined in favor of a valorization of the role of the photojournalists craftsmanship, character, and conscience (Buell, 1999; Orvell, 2003). Of course, it is a testament to Uts craft as a photographer that he produced such a stunning picture and to his character and conscience that in the aftermath of the explosion he helped the injured girl to get medical treatment for her burns. But emphasizing these facts can lead too neatly to

Accidental Napalm Attack

409

discourses of artistry, rescue, and redemption, and it is important not to allow these discourses to over-determine our reading of the photograph in the first instance. At the outset I wish to focus on what happened to Uts film after he delivered it to the AP office in Saigon. Here, a deputy photoeditor viewed the negative that would eventually become Accidental Napalm Attack. This negative was different from the one that is now an iconic image of the war. The image viewed by the deputy photo editor is composed in the following way: in the immediate left foreground there is a boy in a short-sleeved shirt and a younger child; in the centre of the frame, a naked girl with arms outstretched; to the right, two more clothed children running hand in hand; behind the children and to the right are six soldiers, also running, and a photographer manipulating his camera. After examining this relatively complex image the deputy photoeditor summarily rejected it because it showed full frontal nudity, something U.S. newspapers wouldnt carry (NBC destroyed their film footage for the same reason). By chance, later the same day, chief photoeditor, Horst Faas, reviewed the days work and decided to overrule the earlier decision and wire the photograph to New York.2 This process of selecting and deselecting images in compliance with an institutional, commercial, and ideological set of precepts is referred to as gatekeeping (Bailey & Lichty, 1972, p. 221). In this case, U.S. newspapers had strict rules that required events to be reported with propriety, with full frontal nudity not permitted. As well as the prohibition of nudity, other constraints more specific to the representation of war were also applied. Photographs of body parts, dismemberment, evisceration, torture, and sexual violence (especially as these acts pertained to U.S. troops), for example, could not be published. Photojournalists aware of these rules would not generally waste film on material that would later be deemed unusable. As a result, all the subject matter listed above, the everyday facts of life for Vietnamese civilians and soldiers fighting in the war on both sides, is largely missing from the archival photographic record. Furthermore, the gatekeeping activities of picture editors made doubly sure that the published photographic record was even more thoroughly sanitized. As such, the decision taken by the deputy picture editor at AP might be understood as the material manifestation of this ideologically determined screening process, the end result of which would usually be the shielding of U.S. newspaper readers and television viewers from the horrors of war. What is interesting in this case, though, is that the photograph was wired to New York and, as we know, widely published. So, the process of regulating graphic images of war is not monolithic, nor immune from disruption. Stuart Hall describes how the process of selecting photographs with news value is informed by a number of different factors that are not reducible to any singular overarching ideological design. Hall observes that photojournalists, picture editors, and the readers of newspapers demand that a news photograph be contemporaneous with the event it describes and that it has impact, resonance, controversy, and drama. The higher the number of these properties a photograph displays, the higher the likelihood of the photograph making it past the gatekeeper and onto the front page (Hall, 1980). While Accidental Napalm Attack transgresses

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

410

G. Westwell

the need to shield the viewer from the horrors of war (hence the hesitancy in wiring the photograph), it also displays in abundance all of Halls news values. As such, the decision to the wire the photograph to New York, and its subsequent publication, indicates that the demand for controversy and drama may on occasion come into conflict with the commitment to regulation. Or, to put it another way, the agreed rules of regulation (which usually reflect the long-term interests of a political ideology, in this case to show war in a relatively favorable manner) may come into conflict with the short-term commercial impetus driving day to day news production. In light of this, further small-scale amendments to the photograph made prior to publication speak of the ways in which this potential conflict, or contradiction, was managed. For example, before the photograph was transmitted to New York, a technician was instructed to remove a shadow covering the girls groin (Chong, 1999, p. 74). This technical intervention was deemed necessary because it was feared that this shadow might be mistaken for pubic hair and that this might mislead the viewer into thinking the girl was an adolescent or adult. This alteration points to the fact that part of the rationale for transgressing the prohibition on frontal nudity is that the picture shows a child.3 In Western culture, children are generally understood to be pre-social, pre-sexual, apolitical, and innocent, and the technical manipulation of the photograph in this case ensures the foregrounding of these connotations at the expense of the complicating signifier of adult Vietnamese womanhood. The figure of an injured child is also able to function as a symbol of Vietnam more generally* nave, helpless, in need of paternal protection*in ways consonant with the dominant discourse used to describe the war. In contrast, the pubic hair as signifier of adult sexuality and adult consciousness would have lent greater agency to the Vietnamese victim and demanded a different, more complex, response from an adult viewer in the U.S. I contend that this more complex set of connotations would have tipped the picture editors towards censure and the photograph would never have seen the light of day. The gatekeeping decisions and technical manipulation of the photograph, in effect, determine the photographs central subject in advance as the story of a young, innocent girl burnt by napalm. By way of contrast, other photographs from Trang Bang showing a baby and infant with fatal and disfiguring injuries were discarded because they were deemed too shocking. Indeed, it is a marked feature of Accidental Napalm Attack that the girls burns are not clearly visible. The gatekeeping process here seems to point to the fact that in comparison with the alternatives, Accidental Napalm Attack was selected precisely because it was easier to look at, not more difficult as Hariman and Lucaites claim (2007, p. 179). Ultimately, this process of selection and technical manipulation ameliorates the shock value of the photograph and finely calibrates its controversial elements (ensuring it retains its value within the business of news production) in order to remain within the bounds of the general sanitized view of the war. This manipulation of the photograph by media professionals at AP and the alteration of its potential ambiguity to ensure that it would play more comfortably on newspaper front pages is

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

Accidental Napalm Attack

411

evidence that a strong ideological conditioning of the events at Trang Bang was already underway before Accidental Napalm Attack was even wired to the U.S. Much of the critical literature relating to Accidental Napalm Attack focuses on the way the photograph can be taken to be a critique of the U.S.s prosecution of the war in Vietnam. These accounts depend heavily on the central subject*a girl burnt by napalm*as established by the gatekeepers at AP. Marita Sturken writes that:

Because [the girl] is a young, innocent victim burned by American napalm, the image is a serious indictment of the United States methods of conducting war . . . [And that the] expression of disbelief on [the girls] face is emblematic of Americas disbelief at what we did. (1997, p. 92)

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

Similarly, Hariman and Lucaites argue that the photograph provides the viewer with an experience that is traumatic, almost akin to experiencing such an event in person. This reading is predicated on the identification of pain as the central connotation of the photograph. They write,

The little girl is naked, running right toward you, looking right at you, crying out. The burns themselves are not visible, and it is her pain more precisely, her communicating the pain she feels that is the central feature of the picture. Pain is the primary fact of her experience, just as she is the central figure in the composition. (2003, p. 40)

They argue that this sense of pain, and the indifference of the soldiers to it, creates a sort of breakdown of a stable sense of propriety, decorum, and even, reality. That the photograph, . . . freeze[s] the spectator in a tableau of moral failure (2007, p. 182). And that,

Like the explosion still reverberating in the background, the photograph ruptures established narratives of justified military action, moral constraint, and national purpose . . . The picture creates a searing eventfulness that breaks away from any official narrative justifying the war. (2007, p. 176)

By this line of reasoning, the viewer responds to the traumatic impact of the photograph with what might be called a reflexive moral outrage, a powerful emotional response based on empathy that seeds a commitment to changing the circumstances that have allowed such an event to occur. Taking this kind of interpretation to its extreme, Denise Chong claims that, through the outcry that attended its publication, this picture stopped the Vietnam War (1999, p. xiii). In these post facto accounts it is claimed that the photograph acted on at least some its viewers in this way upon its initial publication, only having this potential tamed by subsequent revisionist media and cultural practices. However, the analysis of the process of pre-publication gatekeeping presented above indicates that it was precisely these elements*the fact that a child is at the centre of the event, the fact that her injuries were not obvious*that are were made more pronounced in order to make the photograph more palatable. This fact suggests that any reading that places these

412

G. Westwell

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

elements at the center of their interpretation should be approached with some skepticism. Indeed, this early manipulation of the photograph by gatekeepers at AP indicates that efforts were being made to make the image compatible with contemporaneous reporting of the war, a fact that scholarly accounts which advocate the photographs explicit antiwar design might find uncomfortable. It is true that the photograph appeared at antiwar demonstrations across the U.S. and in these contexts it certainly contributed to a sense of anger that the U.S. government had refused, time and time again, the possibility of peace in Vietnam (Hagopian, 2006, p. 217). Yet, this use of the photograph was not widespread nor consonant with the way the image was disseminated in the mainstream media. As we shall see, a close examination of the photographs dissemination in context indicates how the photographs implicit design (already in the process of being teased out by the gatekeepers at AP) was consolidated and extended upon publication, and that this design is not easily squared with the claims that the photograph activates reflexive moral outrage. During the 1960s, television had become the dominant media form, corroborating, and in many cases superseding, print journalism, and it was here that Accidental Napalm Attack was first seen. On June 8 NBC used the photograph in support of its reporting of the deadly accident at Trang Bang (Goldberg, 1991, p. 242). On broadcast, the photograph was cropped to remove the photographer from the righthand side, thereby masking the photographic means of production and eliding the subjectivity of the photographer and his point of view. More significantly the crop resulted in a shift in the girls position within the composition from slightly right of centre to dead centre, thus providing a focal point for the viewers gaze. As a result of this crop, the screaming boy, who tends to draw the eye in the original composition, is somehow lost in the foreground. Interrogating this shift in emphasis, Alison Ravenscroft asks:

Could it be that, strangely, Kim Phuc is more bearable*more intelligible*than the face of this small anonymous boy with his mouth agape in horror? Is there an elision of the boy here in the very process that foregrounds the young Kim Phuc and makes her suffering iconic? (2004, p. 510)

Just as earlier manipulation of the image emphasized that this was a girl and not an adult woman, the further cropping of the photograph for use on television privileges the girls experience through a shift in the spatial relations between the different subjects in the photograph brought about by careful framing. As the girl is brought centre stage, other stories are pushed to the sidelines: not just the story of the boy, as Ravenscroft rightly observes, but perhaps even more significantly the story of the ARVN soldiers and the photojournalists. The image is shifted towards the universal, detached from its complex and contingent relation to the events at Trang Bang and the wider war. On June 9 The New York Times published a version of the photograph almost identical to the one used in the NBC news broadcast on its front page with the

Accidental Napalm Attack

413

caption: Accidental napalm attack: South Vietnamese children and soldiers fleeing Trangbang on Route 1 after a South Vietnamese Skyraider dropped bomb. The girl at center has torn off burning clothes. A written account of the events at Trang Bang appeared inside the paper on page nine. The caption on the front page stresses the lack of U.S. involvement in the accident, while the accompanying article locates the event in relation to the increasing confidence and military success of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and NLF and to other friendly fire incidents. The contextualization of the image here is consonant with the qualified reporting of the war in the early 1970s, during which time the mainstream media remained largely on-side with Nixons policy of Vietnamization (the heavy bombing of North Vietnam and Cambodia, and the shifting of the burden of fighting from U.S. to South Vietnamese troops) (Hallin, 1986, pp. 89). This favorable coverage provided the context for the reporting of the incident at Trang Bang (Hallin, 1986, p. 260). Accidental Napalm Attack certainly has the potential to produce powerful feelings of shock and empathy for the girls pain. However, read into this contextualizing news discourse, these feelings are channeled with the grain of a consensus position, i.e. that the U.S. should push towards peace with honor and withdraw from a war that barely concerns it anyway. Understood in this way, and in contrast to its valorization as an avowedly antiwar statement, the photograph is simply one element in the framing of the war as a predominantly Vietnamese concern in which the U.S. has a duty of care to help South Vietnam protect itself from communist aggression. Of course, the photograph remained available to be appropriated by the antiwar movement, but in terms of the circulation of the image in the mass media, a consensus-driven view was predominant.4 As such, any claim that at the time of its publication Accidental Napalm Attack constituted a key antiwar statement must be treated with considerable skepticism. Follow up stories published in newspapers and broadcast on television in the days following the events at Trang Bang tended to corroborate the tendency to sanitize the photograph, a tendency that had been emphasized by the gatekeepers at AP, and that had been made more pronounced by editors at NBC and The New York Times upon initial publication. For example, on June 11 The New York Times ran a brief follow up story on page 17 naming the girl in the picture as nine-year old Phan Thi Kim Phuc and describing her recovery in a Saigon hospital. (I have intentionally not used her name in this article up until this point to emphasize how the image*showing a girl but not the named girl, Kim Phuc*would have functioned on its initial publication). Then, on August 9, The New York Times illustrated its front page with a picture of Kim smiling at a nurse at the Barsky Centre in Saigon. The accompanying text, under the headline, Napalm girl recovering in Saigon, informs that Kim has almost recovered from her burns as a result of the work of U.S.-trained Vietnamese plastic surgeons working at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funded hospital. This follow up story*note the use of the label Napalm girl here, a distillation of the central dynamic detailed thus far*suggests a redemptive ending for the photograph in which U.S. aid and infrastructure results in Kim Phucs survival, recovery and recuperation.

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

414

G. Westwell

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

In each of these follow up reports, Kims gender is emphasized. Marita Sturken puts it the following way: As a young, female, naked figure, Kim Phuc represents the victimised, feminised country of Vietnam (1997, p. 92). This construction of the Vietnamese people as feminized was common in U.S. political and popular culture in the 1960s and 1970s, a legacy of colonialist discourse in which the Third World is presented as feminine, helpless and childlike in order to legitimize the need for the help of the First World. As such, Kims childish innocence, her feminine vulnerability, and her need for medical care, provide a rationale for further involvement by the U.S. or its proxies. As noted above, the central argument of critics such as Hariman and Lucaites and Sturken is that Accidental Napalm Attack is an antiwar image and that a redemptive or therapeutic narrative of healing only becomes available as a result of considerable ideological reenactment and rescripting (Sturken, 1997, p. 94). However, close analysis has demonstrated that picture editors in Vietnam, television news producers, and newspaper editors in the U.S., as well as journalists writing follow up stories that described Kim Phucs story of recovery, shepherded the photograph in line with the prevailing hegemonic view of the closing stages of the war in the early 1970s. Kims Story Accidental Napalm Attack was reproduced in different media forms and contexts in the years following the end of the war. As such, the photograph formed part of a wider struggle within the U.S. to reconcile internal divisions engendered by the war and to come to terms with the fact of defeat (the U.S. withdrew its last troops from Vietnam in 1973, and the country was unified under communist rule in 1975). During the late 1970s, the war remained a highly contested and politicized issue. However, in the 1980s the New Rights forceful conservative and nationalist agenda (replete with a return to a belligerent foreign policy) did not sit comfortably with this divisive legacy. As a consequence, the war was subject to a revisionist project designed to reclaim credibility for the military and rebuild national self-esteem. One of the key strands of this project was an insistent focus not on the war itself (and its political, geographical, and symbolic complexity) but on the experience of the Vietnam veteran, who, according to revisionist logic, had merely done his patriotic duty in difficult circumstances. As Keith Beattie notes, healing the wounds became the dominant metaphor for rendering the war less divisive a decade after its end (Beattie, 1998, p. 142). The filtering of the experience of the war through that of the Vietnam veteran enabled key aspects of that experience to be screened out: in particular, the motivations and struggles of the Vietnamese, and the mistakes and misjudgments of politicians and policymakers. By such means, the complex history of U.S. foreign policy and international relations was transformed into individual experience and the wider culture accommodated, and even celebrated, this experience. It was as a result of this process, in confluence with many others, that by the early 1980s the divisive and troubled memory of the war in Vietnam had been largely resolved and this had

Accidental Napalm Attack

415

enabled the U.S. to reclaim faith in its foundational narratives of masculine, military, technological, and political superiority. As Andrew Martin argues, . . . barely six years after the war in Vietnam had been brought to a painful and unsatisfying end, most of the fundamental ideological and symbolic preconditions that had brought it into being were back again (1993, p. xxi). It was within this revisionist moment that Accidental Napalm Attack returned to the public sphere after a period of abeyance. Denise Chong describes how, after the wars end, the Vietnamese government had encouraged Kim Phuc to talk about her experiences (as an illustration of the barbarity of the U.S.) and to describe her struggle to cope with her injuries (as a symbol of Vietnamese bravery and resilience) (1999, pp. 191219). In this role she was also made available to Western journalists interested in stories of post-war Vietnam. Perry Kretz, a writer for the German magazine, Stern, was the first journalist to interview Kim in 1980. Kretzs report emphasized Kims struggle to overcome her injuries and bemoaned the lack of adequate medical facilities in Vietnam. Later, in 1984, Kretz persuaded the Vietnamese authorities to allow Kim to travel to Germany for surgery and included this intervention as part of a follow-up story. Kretzs journalism echoed the way The New York Times had reported on the treatment of Kim at the USAID-funded hospital in Saigon immediately after she was injured, as well as mirroring the discourse surrounding U.S. Vietnam veterans more generally. Kretzs carefully stage-managed journalistic engagement also rehearses the claim that Kims care is more adequately handled outside Vietnam, with the First World placed in the role of Kims savior. Once again, as it did upon initial publication, Accidental Napalm Attack offers a simplistic view of the war*positing a dependent and needy Third World, victim to totalitarianism, and a crusading, technologically and morally superior West. Ten years later, in 1993, on her return to Cuba from a honeymoon in Moscow, Kim sought political asylum in Canada, and in May 1995 agreed to sell her story to Life magazine. The Life magazine article was illustrated with an award-winning photograph in which Kim is shown wearing a black dress with a low-cut back that shows the scars across her upper torso and right arm; she cradles her son, Thomas, in her arms. Once again, the Life magazine photograph extends designs already put in place at the time of Accidental Napalm Attacks initial inception and dissemination. For example, Thomass lack of clothes, unblemished skin and relaxed posture indicate someone untouched by the war and we are witness to the healing of Kims wounds, this time with a clear articulation of a therapeutic coming to terms with her experience. As Hariman and Lucaites note, the foregrounding of Kims reproductive capability and the powerful image of her holding her son testify to her internal health (2003, p. 46). Crucially, Thomas will also grow up Canadian, and therefore Western, relaying something of the desired future of Vietnam more generally, which in the 1990s (through the application of crippling trade sanctions) the U.S. was pressuring to adopt a free market economy.5 We are also told that Western doctors have successfully treated Kims pain, that she has converted from Cao Daoism to Christianity, and that she has renounced communism. Her sexuality, so carefully controlled in the initial photograph through the emphasis placed on her

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

416

G. Westwell

pre-adolescent body, is figured in relation to her role as a mother and in her dedication to her family above all else. Hariman and Lucaites note that the Life article . . . recodes years of deadly violence against a people as a story of how one individual has been wounded. It recodes questions of justice as a rhetoric of healing (2007, p. 188). The documentary, Kims Story*The Road From Vietnam (ITV, UK, 1997), provides a useful distillation of many of the key dynamics found wherever and whenever the photograph is reproduced. Taking the form of a journey, the film shows Kim traveling from Canada to the US to meet the various people who were involved in the production of the image and who cared for her. In a key sequence in the film Dr Loc Nguyen (who cared for Kim after the attack) and Hyung Cong Nick Ut show Kim photographs of her treatment and of her return to her village. Here, Kim becomes the viewer of her own image and is given authority to determine the photographs meaning. Her reading focuses on personal bravery, motherhood, love, spirituality, and forgiveness. Later in the film, a U.S. doctor describes Kims adaptation as fantastic and states that she has turned her injury into something good and in another key scene Kim addresses a class at a U.S. university and a student describes Kim as an angel who has come down to talk to us. A voice-over informs the viewer that Kim wanted to transform her experience into a positive bequest for her child and for all other children. Kim visits the Vietnam Veterans War Memorial and is invited to attend Veterans Day. She is shown making a short speech of forgiveness that is reported in the national press. The documentary ends with a scene in which Kim meets with and forgives U.S. Army Captain John Plummer, who claims he gave the order to drop the napalm (a claim that has subsequently been challenged). As well as telling Kims story, the documentary also valorizes the role of Ut, and the news media more generally. The film begins with a montage sequence that includes film footage and other photographs shot at the time but never broadcast or published.6 The footage shows Kim asking various members of the press for help and being given a drink of water. These images reverse, under carefully controlled conditions, the editing out of the photographer caught on camera in the original photograph and this reversal allows the story of Ut and ITN journalist Chris Wain to be told. We learn that after taking the photograph the two men drove Kim to hospital, as well as checking on her progress in the days and weeks following the attack. Within a post-1980s revisionist context, this additional narrative strand allows media professionals to construct themselves as ethical and heroic individuals who not only helped injured civilians but also worked to alert the public to an unjust war and in so doing steered the public to insist that the war be brought to an end. As noted above, the valorization of the photojournalist in this way is a very common way of framing iconic news photographs such as Accidental Napalm Attack and this kind of framing cannot but elide initial contexts of production such as those described in this article. One final example will suffice to demonstrate how Accidental Napalm Attack continues to be used to mark the war in Vietnam in culturally/ideologically limited

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

Accidental Napalm Attack

417

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

and convenient terms. The feature film Bright Shining Lie (1998), based on Neil Sheehans 1988 bestselling biography of John Paul Vann, shifts between the individual story of Vann and the wider historical narrative of the war. In doing so, the film reconstructs a number of iconic photographs, including Accidental Napalm Attack. The precise positioning and arrangement of the dramatic reconstruction of the photograph within the films narrative is telling. Vann is shown returning to Vietnam for a second tour or duty in March 1965. Working for the Civilian Aid Program, he is stationed at a village called Bao Tre and fixes the roof of a local school, sidestepping the systemic corruption of the ARVN. In doing so he disrespects a local ARVN commander who then gives the NLF permission to attack the village. Further, to punish Vann, the ARVN commander calls in an air strike on the village. In the sequence depicting this air strike, clear references are made to the film and photographic representations of the napalm strike at Trang Bang. Although the sequence is a relatively short one, its position in the narrative is pivotal and instructive: the film shows that the incident has been precipitated by Vanns moral and heartfelt attempt to help a group of Vietnamese civilians who are either children, female teachers, or portrayed as feminized and child-like. The ARVN and NLF are shown to be working in cooperation in pursuit of financial gain, and against the U.S., and that, in effect, the napalm strike and its consequences are the result of innate corruption within Vietnamese society. The designs implicit in the photograph work to reinforce the films narrative in a way that allows the U.S. to be absolved of blame, i.e. they acted in good faith to protect innocent people subject to depravation caused by powerful self-interested groups within their own society. That the Accidental Napalm Attack photograph is pivotal to the articulation of this reductive and revisionist view is the consequence of the ideological processes described in this article. These tendencies are further augmented by the relocation of the image in time: the events at Trang Bang actually took place in 1972 but the photograph*and its freight of meaning*is shifted in time back to 1965. This has the effect of suggesting that the war was already an intractable, wholly Vietnamese affair, even during its early stages, thus further absolving the U.S. of responsibility as a key agent in the destabilization of the country. Conclusion Hariman and Lucaites note that:

The photograph of Accidental Napalm is repeatedly tamed and in a multiplicity of ways: by the banality of its circulation, by personalising the girl in the picture, by drawing out a liberal narrative of healing, by the segue into the celebrity photo of Kims regeneration, and more. (2003, p. 49)

Yet, the use of the word tamed here suggests that at some point the photograph was untamed, that it had the power to disrupt and unsettle. This article has demonstrated that this way of thinking is flawed and that the photograph, while challenging, was not politically inflammatory at the time of its publication. Contrary

418

G. Westwell

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

to the claims in much critical writing about Accidental Napalm Attack, the connotations of the photograph and its cultural/ideological function have remained relatively stable from its inception, where it was shaped by the gatekeepers at AP and dovetailed into the prevailing hegemonic discourse by editors at The New York Times, to the present day, where it is largely used to corroborate revisionist and/or palliative accounts of the war. From the moment Uts negatives were scrutinized at the AP headquarters in Saigon, a process had begun in which Accidental Napalm Attack would be carefully managed in order to amplify certain elements that would make it possible to view the image in a relatively positive light. As a result, the complexity of the war in Vietnam, a war that divided the U.S., destroyed Vietnam, and destabilized much of Southeast Asia, is elided, traduced to universal themes and given a redemptive ending. George Esper, APs bureau chief in Saigon in the early 1970s, reflected that: [The photograph] captures not just one evil of one war, but an evil of every war (Esper in Chong, 1999, p. xiii). Espers comment stands as the photographs preferred reading (reproduced time and time again in documentaries, news reports, and in critical writing) and this article has shown how this preferred reading is the result of cultural/ideological processes that condition iconic images and ensure that while these images may appear to speak of atrocity they can in fact be co-opted into hegemonic views of historical events. To be fair, Hariman and Lucaites do acknowledge that iconic images are very often co-opted in this way:

Popular images disseminated, promoted and repeatedly reproduced by large-scale corporations and seamlessly sutured into the material practices of ordinary life* whether documenting victory or disaster, surely these images exemplify ideology at work. Look at them critically, and it is all there: the production of truth by a technological apparatus of surveillance; the gaze of social authority and its objectification of the other; fragmentary representations of events that reinforce dominant totalising narratives; artfully manufactured sentiments ranging from patriotism to grief used to justify state action; the reproduction of exploitative conceptions of race, class, and gender as if they were the natural order of things . . . (2007, p. 2)

Yet, Hariman and Lucaites also seek a redemptive dimension for the iconic image based on the potential it displayed upon its initial publication to activate reflexive moral outrage. They argue that photographs such as Accidental Napalm Attack are necessary fulcrums around which the public sphere pivots in a negotiation between power elites and the wider public. These fulcrums provide citizens with . . . a reflexive awareness of social forms and state actions that can lead to individual decisions and collective movements on behalf of democratic ideals (2007, p. 3). Hariman and Lucaites point to the traumatic impact of Accidental Napalm Attack and to subsequent provocative and progressive appropriations that are able to . . . articulate patterns of moral intelligence that run deeper than pragmatic deliberation

Accidental Napalm Attack

419

about matters of policy and that disrupt conventional discourses of institutional legitimacy (2003, pp. 4954). That the public sphere might cultivate a reflexive awareness through an engagement with the contingencies and complexity of powerful iconic images is a nice idea in principle, but it can only really function in practice if there is actually something provocative and challenging to look at in the first place. If the account presented here has been persuasive, the initial shock value of Accidental Napalm Attack has been overstated and therefore the photographs ability to foster this reflexive awareness similarly so. Contextualized within the stabilizing discourse of mainstream newspapers, television documentaries, and feature films, it becomes more and more difficult to glimpse any immanent progressive potential that would enliven and enrich the public sphere in the way that Hariman and Lucaites wish to argue. It seems that the desire for redemption prevalent in the publication and recirculation of Accidental Napalm Attack is also a feature of some communication studies scholarship. Perhaps it is the case that the reading of iconic photographs is often filtered through the critics feelings on viewing the photograph in the present, as well as on memories of the image from the time of its initial publication, memories that may well be faulty. Perhaps there is a tendency to produce somewhat nostalgic readings driven by a desire to find loci within the public sphere where certain progressive ideals associated with the civil rights and antiwar movements might be reanimated. However, it is important that the political appropriation of Accidental Napalm Attack by antiwar protesters in the 1970s (a fact certainly worth celebrating) should not be mis-remembered as a moment in which the mainstream news media behaved in a counter-hegemonic manner. Scholars adopting contextual and historical approaches to other iconic photographs of the war in Vietnam have tended to reach similarly skeptical conclusions. For example, Lisa M. Skow and George N. Dionisopoulos describe how newspaper editors adopted a number of strategies designed to explain and justify the famous photograph of the immolation of a Buddhist monk (Skow & Dionisopoulos, 1997, pp. 393409). Robert Hamilton, examining the photograph of the summary execution of a NLF suspect within the context of wider newspaper coverage of the Tet Offensive, concludes that any anti-war connotations are contained and defused within an ideological framework of preferred meanings put in place by the careful combination of image and text (Hamilton, 1989, pp. 178180). And Kendrick Oliver argues that even the photographs (and wider reporting) of the massacre of civilians by U.S. troops at My Lai (perhaps the most difficult event for the U.S. to reconcile with hegemonic views of war) was very quickly shifted from a traumatic and disruptive shock to a set of limited liabilities (Oliver, 2004). Case studies relying on historical and contextual analysis tend to discover that iconic images of the kind analysed in this paper offer their viewers preferred readings that run with the grain of hegemonic views of the historical event under description. This premise should be a default starting position for all scholars working on iconic photographs as they appear in mainstream news discourse and the public sphere.7

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

420

G. Westwell

One further example will indicate the necessity of adopting this default starting position. On 18 May 2010, BBC Radio 4, broadcast Its My Story: The Girl in the Picture, a radio documentary that recounted the story surrounding the publication of Accidental Napalm Attack and tracked the now familiar narrative of Kims story. The documentary also staged a meeting between Kim Phuc and Ali Abbas. This meeting is telling: in 2003, at the age of 12, Abbas was severely injured in a U.S. rocket attack on Baghdad. A photograph showing Abbas immediately after the operation to amputate both his severely burned arms became an iconic image during the post-invasion period. This (seemingly irredeemable) graphic image of an injured child was framed by follow up news reports in ways that stressed Abbass recovery People Magazine, and a number of newspapers, including the Daily Mail, even went as far as to claim that they had been instrumental in his rescue and recuperation. A book, The Ali Abbas Story: The Moving Story of One Boys Struggle For Life, was published, making even more pronounced a redemptive narrative arc almost identical to the one described in this article (Warren, 2004). On May 13 2007, A CBS 60 Minutes feature called How Ali Beat the Odds, described how a stray U.S. bomb had led to Abbass injuries but that U.S. Marines quickly embarked on a mission of salvation, taking Abbas on a dangerous trip to Kuwait where he could get better treatment. As these scant examples make painfully clear, the media coverage of Abbas shocking injuries worked in broadly similar ways to those described in this article in relation to Accidental Napalm Attack. In the BBC Radio 4 broadcast, Kims interaction with Abbas repeats the familiar discourse of love, forgiveness, and healing; although this time applying these to Abbass experience and by association the conflict in Iraq. Here, the revisionist discourses used to salve the trauma and difficulty of an earlier war are applied to current one, binding both in such a way as to discourage critical discourse. Here, the war in Vietnam*a war that might have offered an instructive and precautionary point of comparison*instead becomes part of a wider rhetoric of redemption and affirmation. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag (2003) explores the myriad ways in which even the most disturbing images of atrocity can be brought in line with prevailing ideological view points. She notes that images of atrocity are produced largely to satisfy the news industrys appetite for sensational images, and that through contextualization by written discourse and processes of re-enactment, revision, and habituation, these images are carefully controlled and their potentially radical meanings curtailed. For Sontag, hegemony creates . . . substantiating archives of images, representative images, which encapsulate common ideas of significance and trigger predictable thoughts, feelings (Sontag, 2003, p. 77). As demonstrated in this article, Accidental Napalm Strike is precisely such an image; its deployment in the present now bound by common-sense and revisionist logic. Sontag argues that this tendency can be resisted through a more active form of viewing in which a skeptical approach to photographs of war and atrocity is fostered through the asking of a series of questions: What caused what the picture shows? Who is responsible? Is it excusable? Was it inevitable? Is there some state of affairs which we have accepted up to now that ought to be challenged? (Sontag, 2003,

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

Accidental Napalm Attack

421

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

p. 105). Accidental Napalm Strike certainly comes to life in interesting ways as a result of asking these kinds of questions. For example, we learn that the journalists at Trang Bang were actually initially reluctant to help Kim because they were constrained by deadlines that required them to get back to Saigon before nightfall. This fact reminds the reader that humanitarian impulses (often celebrated by the media) were in fact in a fine balance with commercial imperatives (Chong, 1999, p. 68). Also, rather than simply following Kims narrative arc of survival, healing, and redemption, we might contemplate the story of her family. Kims brother died in the attack and their business was ruined. Due to the terrible legacies of the war (not least the U.S. trade embargo kept in place until 1994) their lives are a constant struggle to the present day (Chong, 1999, p. 69). We might also seek to go beyond the culturally/ideologically curtailed view of the war presented by news photographs such as Accidental Napalm Attack. Philip Griffith Joness disturbing pictures of Vietnamese children born with congenital defects as a result of the legacies of chemical agents used by the U.S. military draw attention to the long-term effects of war and the impossibility for many people of ever moving on (Griffith Jones, 2004). These disquieting, anti-iconic images more than adequately counter the hegemonic cultural memory of the war sustained by photographs such as Accidental Napalm Attack. Notes

[1] The photograph has a number of different titles, including Accidental Napalm Attack (The New York Times, upon initial publication), Children Fleeing a Napalm Strike (Goldberg, 1991; Orvell, 2003), Napalm Girl at Trang Bang (Buell, 1999) and Accidental Napalm Strike (Hariman & Lucaites, 2003). Each of these titles steers the viewer to understand the image in a particular way and is indicative of processes of reenactment and revision. In order to anchor the photograph as much as possible in the moment of its inception I have chosen to use the title that initially accompanied the photograph when it was rst published in The New York Times. Fass recounts this in the television documentary, Kims Story: The Road From Vietnam, (UK, ITV, 1997). It is a signal of changing regulatory regimes that newspapers today would be much more reluctant to publish images of child nudity than adult nudity. The appropriation of the photograph by projects that can be said to be counter-hegemonic was a feature of the antiwar movement and continues to the present day in lms such as Rebecca Barons Okay Bye-Bye (1999) and Sam Greens The Weather Underground (2002). However, in this article I have focused on the photograph and its after-life as it functions hegemonically. Canadas relationship with the U.S. during the war in Vietnam was complex, and it adds a further symbolic dimension here that Kim seeks refuge in a country that also provided refuge to draft-evaders and conscientious objectors. The lm footage in particular is extremely disturbing and difcult to watch: the other injured and dead children, the soldiers, and Kims interaction with the journalists, all serve to import a complex reality back into the photograph. However, this opening sequence is exceptional in its use of this footage and in general the documentary models the ideological trajectory outlined in this article. On rare occasion an image appears that cannot be squared with this default position. I would argue that this is the case with the photographs of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib.

[2] [3] [4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

422

G. Westwell

Interestingly, Hariman and Lucaites suggest that the photographs of Abu Ghraib and Accidental Napalm Attack have a similarly traumatic impact on their viewers (Hariman & Lucaites, 2007, pp. 172174). However, I would argue that this elides crucial differences. First, the photographs of atrocities at Abu Ghraib prison show U.S. protagonists committing systematic abuse with no mitigation that this abuse is an accident. Second, the Iraqi military have no agency within the events shown and therefore the U.S. cannot absolve itself of responsibility. And, third, the photographs were taken for private consumption, thus avoiding the gatekeeping control of the mainstream media. The most important point here is that, as this article has demonstrated, Accidental Napalm Attack was consonant with wider news coverage and reporting of the war in Vietnam, something that cannot be said of the photographs of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib.

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

References

Bailey, G. A., & Lichty, L. W. (1972). Rough justice on a Saigon street: A gatekeeper study of NBCs Tet execution lm. Journalism Quarterly, (14), 221229. Beattie, K. (1998). The scar that binds: American culture and the Vietnam War. New York, NY: New York University Press. Braestrup, P. (1994). Big story: How the American press and television reported and interpreted the crisis of Tet 1968 in Vietnam and Washington. Novato, CA: Presidio. Buell, H. (1999). Moments: The Pulitzer Prize photographs, a visual chronicle of our times. New York, NY: Black Dog and Leventhal. Chong, D. (1999). The girl in the picture: The Kim Phuc story. Harmondsworth: Penguin. Goldberg, V. (1991). The power of photography: How photographs changed our lives. New York, NY: Abbeville Press. Hagopian, P. (2006). Vietnam War photography as a locus of memory. In A. Kuhn & K. Emiko McAllister (Eds.), Locating memory: Photographic acts (pp. 201223). New York, NY: Berghahn. Hall, S. (1980). The determination of news photographs. In S. Cohen & J. Young (Eds.), The manufacture of news: Social problems, deviance and the mass media (pp. 226243). London: Constable. Hallin, D. C. (1986). The uncensored war: The media and Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press. Hamilton, R. (1989). Image and context: The production and reproduction of the execution of a VC suspect by Eddie Adams. In J. Walsh & J. Aulich (Eds.), Vietnam images: War and representation (pp. 171183). New York, NY: St. Martins. Hariman, R., & Lucaites, J. L. (2003). Public identity and collective memory in U.S. iconic photography: The image of Accidental Napalm. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 20(1), 3566. Hariman, R., & Lucaites, J. L. (2007). No caption needed: Iconic photographs, public culture and liberal democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Martin, A. (1993). Receptions of war: Vietnam in American culture. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. Oliver, K. (2004). Not much of a place anymore: The reception and memory of the massacre at My Lai. In P. Gray & K. Oliver (Eds.), The memory of catastrophe (pp. 171190). Manchester: Manchester University Press. Orvell, M. (2003). American photography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Philip Jones Grifth, P. (2004). Agent orange: Collateral damage in Vietnam. London: Trolley Books. Ravenscroft, A. (2004). The girl in the picture and the eye of the beholder: Vietnam, whiteness and the disavowal of indigeneity. Continuum, 18(4), 509524.

Accidental Napalm Attack

423

Skow, L. M., & Dionisopoulos, G. N. (1997). A struggle to contextualise photographic images: American print media and the burning monk. Communication Quarterly, (45), 393409. Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the pain of others. London: Hamish Hamilton. Sturken, M. (1997). Tangled memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS epidemic, and the politics of remembering. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Warren, J. (2004). The Ali Abbas story: The moving story of one boys struggle for life. London: Harper Collins.

Downloaded by [Universitat Oberta de Catalunya] at 17:40 02 April 2012

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Patrol - Vietnam War Roleplay PDFDocument206 pagesPatrol - Vietnam War Roleplay PDFKristin Meyer100% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Vietnam and US Army ChaplaincyDocument38 pagesVietnam and US Army ChaplaincyRichard KeenanNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Vietnam WarDocument74 pagesVietnam WarLinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Vietnam Combat Operations - Volume 1 1965Document14 pagesVietnam Combat Operations - Volume 1 1965PhilatBattlefront100% (4)

- Vietnam VampireDocument9 pagesVietnam VampireSAFEMANDAVENo ratings yet

- Advice and Support, The Final Years, 1965-1973Document591 pagesAdvice and Support, The Final Years, 1965-1973Bob AndrepontNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Vietnam Rescue Mission - Colonel Hambleton Golf Course CodificationDocument102 pagesCase Study of Vietnam Rescue Mission - Colonel Hambleton Golf Course CodificationNicolas MarionNo ratings yet

- 10-1-1969 The Siege of Ben HetDocument64 pages10-1-1969 The Siege of Ben HetRobert Vale100% (1)

- Chain of Command DMZDocument41 pagesChain of Command DMZjose blancoNo ratings yet

- Vietnam Revision BookletDocument14 pagesVietnam Revision BookletIkra Saleem Khan100% (2)

- War Dogs 1Document26 pagesWar Dogs 1api-340421195No ratings yet

- Cid G ProgramDocument10 pagesCid G ProgramSalvador Dagoon Jr100% (1)

- Modern History Olivia Conflict in IndochinaDocument25 pagesModern History Olivia Conflict in IndochinaBryan Ngo100% (2)

- Vietnam Revision NotesDocument14 pagesVietnam Revision NotesZoe TroyNo ratings yet

- A History of VietnamDocument18 pagesA History of VietnamKamoKamoNo ratings yet

- Westmoreland Was Right Learning The Wrong Lessons From The Vietnam War D. AndradeDocument38 pagesWestmoreland Was Right Learning The Wrong Lessons From The Vietnam War D. AndradeRadu PopaNo ratings yet

- YA MWH-B HOMEWORK #09 - Hot Wars During The Cold WarDocument2 pagesYA MWH-B HOMEWORK #09 - Hot Wars During The Cold War3vadeNo ratings yet

- Vietnam War Part 2Document236 pagesVietnam War Part 2georgetacaprarescuNo ratings yet

- Vietnam WarDocument10 pagesVietnam WarGeorgeNo ratings yet

- Donald W. Duncan - The Whole Thing Was A LieDocument13 pagesDonald W. Duncan - The Whole Thing Was A LieTrung MickeyNo ratings yet

- Military History Anniversaries 0601 Thru 061516Document13 pagesMilitary History Anniversaries 0601 Thru 061516DonnieNo ratings yet

- Silver Bayonet Archival MaterialDocument6 pagesSilver Bayonet Archival MaterialArmando SignoreNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22 Section 2Document6 pagesChapter 22 Section 2api-259245937No ratings yet

- CIAResRptsVietnSEASupp PDFDocument67 pagesCIAResRptsVietnSEASupp PDFlimetta09No ratings yet

- Origins of Vietnam WarDocument23 pagesOrigins of Vietnam WarAbhijatyaNo ratings yet

- Xvietnam War White House CIA Foia 04jfkvol4Document506 pagesXvietnam War White House CIA Foia 04jfkvol4DongelxNo ratings yet

- Final Exam - Modern Military History - Matthew SilerDocument21 pagesFinal Exam - Modern Military History - Matthew SilerMatthew SilerNo ratings yet

- An Australian Surgical Team in Vietnam, Long Xuyen October 1967 To October 1968.Document198 pagesAn Australian Surgical Team in Vietnam, Long Xuyen October 1967 To October 1968.CliveBond100% (1)

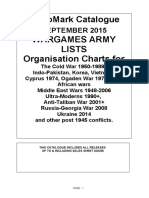

- Micromark Catalogue Wargames Army Lists Organisation Charts ForDocument16 pagesMicromark Catalogue Wargames Army Lists Organisation Charts ForJeffrey Walker100% (1)

- Going To TcheponeDocument12 pagesGoing To TcheponeRobert SpiveyNo ratings yet