Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Science in Medieval Islam

Uploaded by

Hajar AlmahdalyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Science in Medieval Islam

Uploaded by

Hajar AlmahdalyCopyright:

Available Formats

Science in Medieval Islam: An Illustrated Introduction by Howard R. Turner Review by: Imad-ad-Dean Ahmad Middle East Journal, Vol.

52, No. 4 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 628-629 Published by: Middle East Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4329273 . Accessed: 01/05/2012 00:15

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Middle East Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Middle East Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

628 * MIDDLE EAST JOURNAL

of hierarchies.According to such value systems, individuals were destined to belong to a social rank from which they could not and should not escape. To determine the origins of these ideas, the author has looked at the legacy of Greek! Byzantine social thought and to ancient Persian ideas of hierarchy.She argues convincingly that Persianideas of a stable social structure, voiced in such fragmentarysurvivals of Sassanianpolitical writing as the Letter of Tansar and the Testament of Ardashir,provided the foundationfor much of this world view. The division of society into soldiers, priests, merchants and cultivators (or variationsof this division) was taken up by early Islamic intellectuals. A typical feature of these distinctionswas the lowly status assigned not just to cultivators but to merchantsand crafts people as well. By the time of the Saljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk in the 12th century or the philosopher Nasir al-Din Tusi in the 13th, it could be argued thatthe maintenanceof class distinctionsbased on descent and function was one of the most important roles of a good Muslim ruler.Equalitybased on merit might be found in the next world, but such ideas could not be countenancedin this. Marlow investigates these changes by a meticulous use of a wide range of sources in both Arabic and Persian.These include hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) collections, adab (belles-lettres), philosophical works and Mirrors for Princes (works of advice for rulers).Marlow's bibliography and discussion of the origin and context of many of these works are a valuable feature of this book. It is a pleasureto see such a wide variety of material used to illuminate a single theme. As mentionedabove,the authorlooks to boththe tradition the Persiantradition and Greek/Byzantine to discover the roots of hierarchical thought.She might also have consideredthe influence of preMuslim Arab ideas of hierarchy. Admittedlythese are rarely formulatedin literaryterms, but some tribesandindividuals were clearlyacknowledged to have a higherstatusthanothers.As IgnazGoldziher recognized long ago,' much of the social protest in which was apparent the firstcenturyof Islamwas directedat the ashraf, the chiefs of the pre-Islamic

1. "The Arab Tribes and Islam," in Muslim Studies, Vol. 1, tr. S.M. Stern (London, 1967), pp. 45-97.

order,and the importancethey continuedto enjoy in the new Muslim order,ratherthan any Persian ideas of hierarchy. Despite this reservation,it is clear that Marlow has made a majorcontributionto our understanding of early Islamic society and social thought. The work is clear and lucid, free fromjargon and firmly grounded in the text. Students of Islamic history will read it once with enjoyment but find themselves returningfrequentlyto seek out ideas, insights and fascinating nuggets of bibliography. Hugh Kennedy is Professor of Middle Eastern History at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

Sciencein MedievalIslam:An Illustrated Introduction,by Howard R. Turner. Austin:

Universityof Texas Press, 1995. xx + 230 pages. Tables to p. 237. Gloss. to p. 240. Bibl. to p. 246. Illustrationsources to p. 252. Index to p. 262. $40 cloth; $19.95 paper. Reviewed by Imad-ad-DeanAhmad Insofar as the authorof this book has focused on the theme suggested by its subtitle, "anillustrated introduction science in medieval Islam,"he has to done an excellent job. HowardR. Turnerpresents a historical summaryof the subject in a readable, concise and generally accuratefashion. The 106 illustrations of mainly Muslim scientific texts, instruments and structures-all in black and white-are attractiveand pertinent.The book is well organized and interesting, and appropriate for an undergraduate course in medieval science, but the epilogue is disappointing. There he attempts-as so many non-Muslim Western analysts of Islam do-to explain the currentstate of science in the Muslim world in terms of a conflict between reason and revelation. This perspective comes out of Christian history and sheds more confusion than light on the problems and controversies in the Muslim world today. The firstthreechapters introduce reader the the to classical Islamiccivilization(7th to 15thc.), to the forces and bonds that held it together and to the roots of Islamic science in previous Egyptian, and Babylonian, Greek,Iranian Indiancivilizations. These chapters are a good introductionto the subject, but their main flaw is the absence of an

BOOK REVIEWS* 629

of appreciation the role that the Quranicmessage played in the developmentof that science. Chapters four through 12 admirably review medieval Muslims' contributionsin the areas of mathematics, astronomy, astrology, geography, medicine, the naturalsciences, alchemy and optics. In each field, the readercan see how Muslims studied, assimilated, adaptedand expanded upon the knowledge that was producedby earlier civilizations and cultures with which they came in contact. The examples are somewhat biased towards the Hellenistic cultures, a reflection of the author's Western source material, but the existence of other influences is acknowledged. Although the author gives many examples of the increasing importanceof empirical research, he seems to be unawareof the importanceof the fact that the Quranencouragedobservationof the materialworld and provoked Muslim respect for the empiricalaspect of the sciences, in contrastto the rationalisticancient Greeks. Turnerdiscusses the similarity between Ibn al-Shatir's planetary models and those of Copernicus, but does not seem to realize the significance of Ibn al-Shatir's concernfor the empiricalfailings of the Ptolemaic model. Ibn al-Shatir developed a model for the motions of planets (first proposed by al-Tusi) which dispensed with Ptolemy's cumbersome concepts of the "equant" and "eccentric" and described planetary motion by a set of linked epicycles. Copernicus' model is identical to Ibn al-Shatir'swith the epicycles shuffled.Al-Shatir's critique went beyond dissatisfaction with mere technical departures from absolutely circular planetarymotions. Chapter 14 gives an adequateif brief description of the transmissionof Islamic science to the West, but the concluding chaptersare inadequate. Chapter 15 underestimatesthe worth of the individual in the Islamic conception of tawhid. In the epilogue, the authorerrs in seeking to analyze the scientific backwardness of the modern Muslim world by simply taking for granted that the responsibilitylies on a supposed conflict between science and religion. His premise that classical Islamic antipathytowards philosophical speculation and pseudo-science (like astrology) constitutes an anti-science prejudice is untenable. The fact that such alleged attitudes did not prevent medieval Islam from achieving the magnificent scientific feats outlined in the rest of the book

suggests that an anti-science prejudice is a poor explanation for the present state of the Muslim world. The author's presumption,stated without documentation or example, that modern "Muslims attitudestowardthe characterand purposeof science include a broadrange of opposition, with an equivalent range of intensity" (p. 226) is certainlyfalse. The conclusion that the "confrontation between reasoning and revelation as sources of ultimate truthremains active throughout the worldwide Islamic community, with an intensity generally unmatched in the West" (p. 228) is astonishing.Even those Muslims who are fanatical in their opposition to certain aspects of modernity do not share the anti-technology tendencies found among certain "Christianfundamentalists"and among Luddite eco-extremists. It is uncommon to find a Muslim who would admit to any contradictionbetween reason and revelation. The issue of contention among Muslims is, and always has been, whose interpretation of revelationis the most reasonable.Debate about the meaning of religious texts (the signs of Allah in the Quran) was the inspiration for the first 1,000 years of Islamic scholarly endeavors.Muslims also debated the soundness of their competing interpretationsof observations (the signs of God in the heavens and on earth). Any renaissance of the Muslim world will depend not upon choosing science over revelation, but upon employing reason in all debate, whether scripturalor scientific. Imad-ad-Dean Ahmad, Ph.D., President of the Minaret of Freedom Institute, is author of Signs in the Heavens:A Muslim Astronomer'sPerspective 'on Religion and Science (Beltsville: Writers Inc., International,1992).

RecentPublications

CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCUSES Boghos Nubar's Papers and the Armenian Question, 1915-1918: Documents, ed. and tr. by Vatche GhazarAnnotationswere prepared with the assistance of Melia Amal Bouhabib, Mary Ann Cockerill, Cezar Jackson, Wendy C. Scranton, Ben6dicte Spoelders, Frank Tachau, Mary Ann T6treaultand Nancy Wood.

You might also like

- (Adi Setia) Islamic Ethics in Engagement With Life, Health and MedicineDocument41 pages(Adi Setia) Islamic Ethics in Engagement With Life, Health and MedicineHajar Almahdaly100% (1)

- (Zaidi Ismail) The Cosmos As The Created Book and Its Implications For The Orientation of ScienceDocument23 pages(Zaidi Ismail) The Cosmos As The Created Book and Its Implications For The Orientation of ScienceHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Malik Bennabi On Civilization, Alwi AlatasDocument2 pagesMalik Bennabi On Civilization, Alwi AlatasHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- The German Invention of Race PDFDocument7 pagesThe German Invention of Race PDFHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Heideggerian Aesthetics, East and West (Dwyer)Document11 pagesHeideggerian Aesthetics, East and West (Dwyer)Hajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Journal of Muslims in Europe) Framing Islam at The World of Islam Festival, London, 1976Document21 pagesJournal of Muslims in Europe) Framing Islam at The World of Islam Festival, London, 1976Hajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- (Zaidi Ismail) The Cosmos As The Created Book and Its Implications For The Orientation of ScienceDocument23 pages(Zaidi Ismail) The Cosmos As The Created Book and Its Implications For The Orientation of ScienceHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Al-Ghazali of AndalusDocument24 pagesAl-Ghazali of AndalusHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Lata'if Al-Asrar by Raniri Page 11-65 PDFDocument28 pagesLata'if Al-Asrar by Raniri Page 11-65 PDFHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- (Tala Asad) The Idea of An Anthropology Islam PDFDocument31 pages(Tala Asad) The Idea of An Anthropology Islam PDFHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Some Aspects of Sufism As Understood and Practiced Among Malays - CompressedDocument73 pagesSome Aspects of Sufism As Understood and Practiced Among Malays - CompressedHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Books-In-brief Apostasy in Islam A Historical and Scriptural AnalysisDocument28 pagesBooks-In-brief Apostasy in Islam A Historical and Scriptural AnalysisHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Decolonizing International RelationsDocument144 pagesDecolonizing International Relationsaquarianflower100% (4)

- The Achehnese Vol 2Document406 pagesThe Achehnese Vol 2Hajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- (Makdisi) Religion and Culture in Medieval IslamDocument25 pages(Makdisi) Religion and Culture in Medieval IslamHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- The Rhineland MovementDocument13 pagesThe Rhineland MovementHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- A Survey of HindusimDocument720 pagesA Survey of HindusimSaran Kumar MamidiNo ratings yet

- The Achehnese Vol 1Document486 pagesThe Achehnese Vol 1Hajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Master Eckhart and The Rhineland Mystics by Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache Hilda Graef-Rev. PolitellaDocument3 pagesMaster Eckhart and The Rhineland Mystics by Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache Hilda Graef-Rev. PolitellaHajar Almahdaly100% (1)

- (Huston Smith) Postmodernism and The World's ReligionsDocument24 pages(Huston Smith) Postmodernism and The World's ReligionsHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Al-Attas - Islam and SecularismDocument108 pagesAl-Attas - Islam and Secularismbasit_i82% (11)

- (Schuon) The Nature and Arguments of FaithDocument11 pages(Schuon) The Nature and Arguments of FaithHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Why I Am Not A Traditionalist: Hajj Muhammed LengenhausenDocument23 pagesWhy I Am Not A Traditionalist: Hajj Muhammed LengenhausenHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Frithjof Schuon: The Shining Realm of The Pure Intellect - Renaud FabbriDocument143 pagesFrithjof Schuon: The Shining Realm of The Pure Intellect - Renaud FabbriSamir Abu Samra100% (6)

- Confessions of A Disagreeable Man-By Norman LevittDocument9 pagesConfessions of A Disagreeable Man-By Norman LevittHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Scientific Exegesis of The Quran-A Viable Project-Mustansir MirDocument8 pagesScientific Exegesis of The Quran-A Viable Project-Mustansir MirHajar Almahdaly100% (2)

- Confessions of A Disagreeable Man-By Norman LevittDocument9 pagesConfessions of A Disagreeable Man-By Norman LevittHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Scientific Exegesis of The QuranDocument15 pagesScientific Exegesis of The QuranHajar Almahdaly100% (1)

- Viability of Islamic Science-Some Insights From 19th Century IndiaDocument6 pagesViability of Islamic Science-Some Insights From 19th Century IndiaHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- Science Quranand HermeneuticsDocument17 pagesScience Quranand HermeneuticsHajar AlmahdalyNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

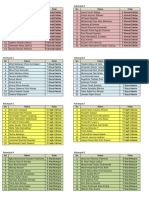

- List of student groups and members by classDocument1 pageList of student groups and members by classDike MaharanyNo ratings yet

- DowerDocument7 pagesDowerabrash111No ratings yet

- Hybrid Essay - Identity and BelongingDocument3 pagesHybrid Essay - Identity and BelongingKurtNo ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu Board Textbooks Class 8 HistoryDocument89 pagesTamil Nadu Board Textbooks Class 8 HistorySachin GondNo ratings yet

- Contribution of Imam HanifaDocument8 pagesContribution of Imam HanifaSinulinding KadafyNo ratings yet

- 1971 Pakistan-India War: Battle of ShakargarhDocument32 pages1971 Pakistan-India War: Battle of ShakargarhAmir Qureshi100% (3)

- University Faculty & Administration Listing (09-10 Catalog)Document14 pagesUniversity Faculty & Administration Listing (09-10 Catalog)tarek221No ratings yet

- An Introduction To Filipino Visual Arts by Rhona Lopez NathDocument1 pageAn Introduction To Filipino Visual Arts by Rhona Lopez NathRhona Lopez NathNo ratings yet

- 05 Chapter 1Document24 pages05 Chapter 1vj_epistemeNo ratings yet

- Malachi Z YorkDocument5 pagesMalachi Z YorkManzini Mbongeni100% (2)

- Bihar Al Anwar Vol 51 52 & 53 The Promised Mahdi English Translation Part 1Document504 pagesBihar Al Anwar Vol 51 52 & 53 The Promised Mahdi English Translation Part 1MAFHHZB100% (10)

- Liste Provisoire ECO SH 2021 2022Document31 pagesListe Provisoire ECO SH 2021 2022Samia SouiatNo ratings yet

- HC 2020Document31 pagesHC 2020MaizatulTaharimNo ratings yet

- Like Joseph in Beauty Yemeni Vernacular Poetry AnDocument550 pagesLike Joseph in Beauty Yemeni Vernacular Poetry Anwei wei100% (1)

- Notice List of Students Successful Enroll Into Kulliyyah of Medic & Denti Intake 20122013Document8 pagesNotice List of Students Successful Enroll Into Kulliyyah of Medic & Denti Intake 20122013Nurhawa MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Boltay Haqaiq by Maulana Muhammad Yusuf LudhianviDocument649 pagesBoltay Haqaiq by Maulana Muhammad Yusuf LudhianviMohammad RadoanNo ratings yet

- Ethics Relevance of Interpersonal Communication inDocument11 pagesEthics Relevance of Interpersonal Communication inPaul RNo ratings yet

- How Mullah Maududi Sank The Muslim Mind FurtherDocument4 pagesHow Mullah Maududi Sank The Muslim Mind Furthersalman_jeddah0% (1)

- بشرى لنا نلنا المنىDocument2 pagesبشرى لنا نلنا المنىAimi AthirahNo ratings yet

- Concept of Knowledge in The Holy QuranDocument15 pagesConcept of Knowledge in The Holy QuranZain ull Abiddin DaniyalNo ratings yet

- Catalogue of Persian Manuscripts in Brit - Museum - Rieu, 1879 - Vol.2 PDFDocument464 pagesCatalogue of Persian Manuscripts in Brit - Museum - Rieu, 1879 - Vol.2 PDFsi13nz100% (1)

- Bukti Kinerja PengajaranDocument21 pagesBukti Kinerja Pengajaranboding1991No ratings yet

- Analysis MariahDocument5 pagesAnalysis Mariahmohammad_shafiq_14No ratings yet

- Genocide WebquestDocument2 pagesGenocide Webquestapi-285213466No ratings yet

- Salaat AbdunoorDocument8 pagesSalaat AbdunoorumerNo ratings yet

- TowersDocument24 pagesTowersDhiegavea Kate BarcenaNo ratings yet

- Transfiguration of The World and of Life in Mysticism - Nicholas ArsenievDocument9 pagesTransfiguration of The World and of Life in Mysticism - Nicholas ArsenievCaio Cardoso100% (1)

- 1.0 Intro To Quran StudyDocument4 pages1.0 Intro To Quran StudyKhaled MohammadNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Ibn-E-BattutaDocument373 pagesThe Adventures of Ibn-E-Battutajawedkhan775488% (8)

- Cleo Malaysia-December 2017Document116 pagesCleo Malaysia-December 2017nts1020No ratings yet