Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Forms of Direct Democracy

Uploaded by

Ali XaiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Forms of Direct Democracy

Uploaded by

Ali XaiCopyright:

Available Formats

Forms of direct democracy - federal level

Numerous different direct democracy mechanisms can be used at federal level in Switzerland. The mechanisms fall into two broad categories: referendums and initiatives - there is no provision for use of the recall in Switzerland. Each mechanism can be used to achieve different results, and has different design features. Referendums Unlike in other countries, in Switzerland it is not the government that decides if a referendum is held on an issue; the circumstances under which referendums are used are clearly prescribed within the country's constitution. The first type of direct democracy mechanism is the mandatory referendum, i.e., a referendum that the government must call in relation to certain important political issues. These are:

A partial or total revision of the federal constitution; Joining an organisation for collective security or a supranational organisation; Introducing urgent federal legislation whose validity exceeds one year, without the required constitutional basis (such legislation has to be submitted to the vote within one year after its adoption by Parliament);

Popular initiatives for a total revision of the constitution; Popular initiatives for a partial revision of the constitution in the form of a general proposition which were rejected by the Parliament;

The question of whether a total revision of the constitution should be carried out if both chambers of Parliament disagree.

The first three kinds of mandatory referendums require a double majority to pass; that is, they must achieve a popular majority (a majority of the votes cast at the referendum) whilst at the same time achieving a majority vote in a majority of the cantons. The latter three, which take place as part of the initiative process, only need a popular majority. Optional referendums can be held in relation to new or amended federal acts and/or international treaties. The optional legislative referendum is held in relation to all federal laws and urgent federal laws which are due to be valid for more than a year. The optional referendum on international treaties is held in relation to international treaties that are of unlimited duration and may not be terminated, and international treaties that provide for membership of international organisations or contain legislative provisions that have to be implemented by enacting federal laws Optional referendums are called if 50,000 signatures are collected in support of a referendum within 100 days, or if eight cantons request a referendum,

and pass with a popular majority. Until 2004, an optional referendum has never been successfully requested by a group of cantons; the first referendum initiated by the cantons was held on 16 May 2004. Initiatives Initiatives can be used to propose changes to the federal constitution. In addition, in 2003 Switzerland adopted a new form of initiative, to be used in relation to more general statutory provisions. Once an initiative is filed, a specified number of valid signatures (i.e. signatures of registered voters) are required in order to force the Federal Council and Parliament to consider the initiative and to hold a referendum on the initiative proposal. Amendments to the constitution can be proposed using two different initiative mechanisms. The popular initiative for a partial revision of the constitution provides voters with the opportunity to propose a draft revision to part of the federal constitution. 100,000 voters must sign an initiative in order for a referendum to be held on the proposal. The popular initiative for a total revision of the constitution also requires the support of 100,000 voters in an initiative. In both cases, the signatures must be collected within 18 months of the initiative being filed. From late 2006, the general popular initiative will be available to Swiss voters. This mechanism can be used to force a referendum on the adoption of a general proposal that will be incorporated on a constitutional and/or legislative level, providing that 100,000 signatures are collected in support of the initiative. Until 2006, initiatives in Switzerland can be submitted as a general proposition or in the text that would be adopted if the initiative measure is successful. However, after the implementation of the general popular initiative, the popular initiative for a partial revision of the constitution will only be accepted in the form of a written text proposition (general propositions in relation to the constitution should be made using the general popular initiative). In response to initiatives which meet the required signature threshold, the Swiss Parliament advises the people on whether to adopt or reject the proposal. In addition, the government is also able to formulate a counterproposal that is included on the ballot. The "double-yes" vote allows voters to approve both the original initiative and the government's response to it, and indicate which of the two measures they prefer. The measure which receives the most support is passed.

Forms of direct democracy - cantonal level

Use of direct democracy is even more extensive in Switzerland's 26 cantons (i.e., state authorities). However, use of direct democracy varies between the cantons; between 1970-2003 Zurich held 457, whilst Ticino held just 53 (the canton of Jura held just 45 referendums, but was only formally established (by referendum) in 1979).

In addition to the referendum and initiative mechanisms used at federal level, the following mechanisms are also used in some or all of the Swiss cantons. Unlike at federal level, the legislative initiative has for some time provided voters in all cantons with the opportunity to propose additions to laws. In some cantons, the administrative initiative can be used to demand that certain work is undertaken in public administration (e.g., building a new school or a new road). In addition, some cantons provide for the initiative to launch a canton initiative, an initiative to force the canton to table a motion to the Federal Assembly. All the Swiss cantons provide for legislative referendums on legislation passed by the cantonal parliament; however, in different cantons, these may be mandatory or optional. Administrative referendums may be held on major public projects that will incur high levels of public expenditure (and may lead to increases in taxes); these are sometime called fiscal referendums. Lastly, administrative referendums may be held on the non-fiscal issues of public administration listed above.

Characteristics of the use of direct democracy in Switzerland

Turnout Swiss voters are given the opportunity to vote in federal referendums on average four times a year. Typically, voters will also vote on a number of cantonal and local issues on the day of a federal ballot. Over the second part of the twentieth century, turnout at federal referendums fell from around 50-70% to an average of around 40%; this mirrored a similar decline in turnout at federal elections from 80% to around 45%. One suggestion is that this comparatively low turnout is due to the sheer number of votes that the Swiss are able to vote in; however, it is argued by many that a far higher proportion of the population is politically active than appears so from the figure of 40%, since it is not always the same 40-45% of voters who vote at each opportunity. Issues Given the numerous opportunities for using direct democracy in Switzerland, it is perhaps not surprising that the variety of issues on which referendums are held is extremely wide. Since 1990, referendums have been held on such diverse issues as:

Banning the building of nuclear power stations; Building new Alpine railways; A new federal constitution; Controlling immigration;

Abolishing the army; Joining the United Nations; Shortening working hours; Opening up electricity markets.

Impact of direct democracy Undoubtedly, direct democracy has played a key role in shaping the modern Swiss political system. Yet it is important to question the actual impact of direct democracy on the legislative issues that, in other countries, are the responsibility of elected representatives. On one reading, it could be argued that the impact has been limited: in the first century of using the initiative (1891-2004), just 14 initiatives were passed in Switzerland. Yet to consider this statistic alone ignores the considerable, indirect impact of direct democracy. Although the majority of initiatives fail, the fact that there has been an initiative, and therefore a campaign, increases publicity surrounding the issue in question and public knowledge of it. This may well increase pressure on the government to introduce measures dealing with the issue, even if it is not required to by virtue of a successful referendum. An initiative might therefore be successful in achieving some of its proponents' aims, even if it is not successful in the sense of having passed. This trend explains why many initiatives are filed but subsequently withdrawn; because sometimes a government chooses to act before an initiative reaches the referendum stage. A further impact of the direct democracy mechanisms within Switzerland is that the government is forced to seek a wider consensus about the statutory (and constitutional) measures that it seeks to introduce than is the case in a purely representative system. In a representative system, the party of government may, in the absence of a large majority, have to develop cross-party consensus on an issue in order to ensure that the measure is approved. In the Swiss system, the possibility of an optional referendum forces the government to ensure consensus with groups outside of Parliament so as to prevent the possibility of such groups seeking to overturn the new legislation. Conversely, the significance of direct democracy in the Swiss system is often cited as the reason for the weakness of Swiss political parties and the relatively low significance attached to normal elections. This is because, given the prominence of direct democracy, political parties are not solely responsible for controlling the federal agenda. In addition, direct democracy often raises cross-cutting issues on which members of political parties might not be in agreement.

You might also like

- Social ChangeDocument11 pagesSocial ChangeRupert BautistaNo ratings yet

- LAWPBALLB209944rStarPr - Gandhian PrinciplesDocument3 pagesLAWPBALLB209944rStarPr - Gandhian PrinciplesSri MuganNo ratings yet

- Theories of DemocracyDocument65 pagesTheories of DemocracySathyaRajan RajendrenNo ratings yet

- Sociology of DevelopmentDocument2 pagesSociology of Developmentsupriya guptaNo ratings yet

- Releationship With Other Social Sciences 5Document43 pagesReleationship With Other Social Sciences 5Lucifer MorningstarrNo ratings yet

- Theories of PunishmentDocument11 pagesTheories of PunishmentRokibul HasanNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three & FourDocument34 pagesChapter Three & FourAsfawosen DingamaNo ratings yet

- PoliticsDocument16 pagesPoliticsrohan_jangid8100% (1)

- Class Struggle - Karl Marx (Revised and Extended)Document15 pagesClass Struggle - Karl Marx (Revised and Extended)CANCER. 7No ratings yet

- Rousseau: Ivan Paul ManaligodDocument28 pagesRousseau: Ivan Paul ManaligodIvanPaulManaligodNo ratings yet

- Liberal: 3.0 ObjectivesDocument11 pagesLiberal: 3.0 ObjectivesShivam SinghNo ratings yet

- Social ActionDocument11 pagesSocial ActionSmaxy boyNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Topic-1: Problems of Minorities in IndiaDocument13 pagesAssignment: Topic-1: Problems of Minorities in IndiaMOHAMAMD ZIYA ANSARINo ratings yet

- Questions On Mill, Bentham and RousseauDocument9 pagesQuestions On Mill, Bentham and RousseauShashank Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Factors Contributing To The Emergence of SociologyDocument2 pagesFactors Contributing To The Emergence of SociologyYousuf Ali100% (2)

- Social Action Theory PDFDocument1 pageSocial Action Theory PDFpuneeth87No ratings yet

- Marxist TheoryDocument5 pagesMarxist TheoryDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Comte PDFDocument150 pagesComte PDFDebajyotibiswasNo ratings yet

- Nature of StateDocument11 pagesNature of StatePrashanthi Gadireddy100% (1)

- Unit-IV (Sociological Thinkers) Emile Durkheim: Social FactsDocument6 pagesUnit-IV (Sociological Thinkers) Emile Durkheim: Social Factsaditya singhNo ratings yet

- Difference - Between - Marxism - and - Leninism #Marxism - Vs - LeninismDocument2 pagesDifference - Between - Marxism - and - Leninism #Marxism - Vs - LeninismSumaira MalikNo ratings yet

- Legal Positivism: EtymologyDocument4 pagesLegal Positivism: EtymologyIvanNo ratings yet

- Topic-Modernisation: Saurabh Sharma Disha Sharma Ritul Jangid Paras Joshi Sonali Thakur Mohit KaushikDocument7 pagesTopic-Modernisation: Saurabh Sharma Disha Sharma Ritul Jangid Paras Joshi Sonali Thakur Mohit KaushikSonaliNo ratings yet

- Shortell, T (2019) Social Types (Simmel)Document2 pagesShortell, T (2019) Social Types (Simmel)Tesfaye TafereNo ratings yet

- Sociology - Sem 1Document31 pagesSociology - Sem 1SathyaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Public AdminDocument17 pagesIntroduction To Public Adminchibuye musondaNo ratings yet

- Nature of Comparative PoliticsDocument2 pagesNature of Comparative PoliticsShaik AfzalNo ratings yet

- Concept of State and NationDocument4 pagesConcept of State and NationM Vijay AbrajeedhanNo ratings yet

- Political Theory Meaning and Approaches 1662521903423Document11 pagesPolitical Theory Meaning and Approaches 1662521903423Sports AcademyNo ratings yet

- Communalism and IndiaDocument7 pagesCommunalism and IndiaLakshay BatraNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism Power PointDocument56 pagesPostmodernism Power PointSusan Hullock100% (1)

- Politiical Sociology (Handout)Document41 pagesPolitiical Sociology (Handout)lateraadejeneNo ratings yet

- Dependency Theory: Concepts, Classifications, and CriticismsDocument30 pagesDependency Theory: Concepts, Classifications, and Criticismsmostafa abdo100% (1)

- Part One: Theory Chapter 1. Justice As Fairness 1. The Role of JusticeDocument11 pagesPart One: Theory Chapter 1. Justice As Fairness 1. The Role of JusticeKamilahNo ratings yet

- Mechanical and Organic SolidarityDocument11 pagesMechanical and Organic SolidarityShivansh JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Sandel On RawlsDocument34 pagesSandel On RawlsalankarsyNo ratings yet

- Law of Three Stages by Auguste ComteDocument3 pagesLaw of Three Stages by Auguste ComteSyed Hassan100% (4)

- 1.4.3.1 Social Action PDFDocument9 pages1.4.3.1 Social Action PDFAnonymous gf2aAKNo ratings yet

- Pluralist Theory of SovereigntyDocument5 pagesPluralist Theory of SovereigntyMuhammad FarazNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four Citizenship: Department of Civics and Ethical StudiesDocument8 pagesChapter Four Citizenship: Department of Civics and Ethical StudiesEyob Desta0% (1)

- Social ControlDocument17 pagesSocial ControlVidya VincentNo ratings yet

- Liberalism: Answer The Questions and Read The TextDocument4 pagesLiberalism: Answer The Questions and Read The Textsophia gudmanNo ratings yet

- Approaches To The Study of Political ScienceDocument20 pagesApproaches To The Study of Political ScienceSrushti BhisikarNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Social and Cultural ChangeDocument6 pagesAssignment: Social and Cultural Changeqasim0% (1)

- Forms of GovernmentDocument2 pagesForms of GovernmentMariniel Gomez LacaranNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Philippine Political SystemDocument4 pagesOverview of The Philippine Political SystemPrincess Hanadi Q. SalianNo ratings yet

- Elements of Sociological ImaginationDocument3 pagesElements of Sociological ImaginationANKITA TEKUR100% (1)

- The Meaning of Social MovementsDocument6 pagesThe Meaning of Social MovementsMano SheikhNo ratings yet

- Rights: Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of DelhiDocument18 pagesRights: Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of DelhiNirbhay GuptaNo ratings yet

- J.S. Mill's On LibertyDocument6 pagesJ.S. Mill's On LibertySzilveszter FejesNo ratings yet

- 26 Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1770 A.D.) : Scanned With CamscannerDocument20 pages26 Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1770 A.D.) : Scanned With CamscannerShaman KingNo ratings yet

- 5) Law and Justice 2019.2020Document48 pages5) Law and Justice 2019.2020Umar MahfuzNo ratings yet

- International Political Economy PDFDocument5 pagesInternational Political Economy PDFsalmanyz6No ratings yet

- Factors That Contributed To The Rise and Development of SociologyDocument3 pagesFactors That Contributed To The Rise and Development of SociologysylvesterNo ratings yet

- Analysis of I Want A WifeDocument5 pagesAnalysis of I Want A Wifeapi-217639607No ratings yet

- English ProjectDocument25 pagesEnglish ProjectNidhi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Nature of Political Science - Why Is It A Social Science?Document3 pagesNature of Political Science - Why Is It A Social Science?awstikadNo ratings yet

- Socialism Assignment PDFDocument13 pagesSocialism Assignment PDFKamal MedhiNo ratings yet

- Direct Democracy in SwitzerlandDocument4 pagesDirect Democracy in Switzerlandgoon baboonNo ratings yet

- Direct Democracy of SwitzerlandDocument5 pagesDirect Democracy of SwitzerlandHardik AnandNo ratings yet

- Ting Vs Heirs of Lirio - Case DigestDocument2 pagesTing Vs Heirs of Lirio - Case DigestJalieca Lumbria GadongNo ratings yet

- Adjectives With Cork English TeacherDocument19 pagesAdjectives With Cork English TeacherAlisa PichkoNo ratings yet

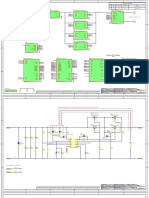

- Scheme Bidirectional DC-DC ConverterDocument16 pagesScheme Bidirectional DC-DC ConverterNguyễn Quang KhoaNo ratings yet

- MDC PT ChartDocument2 pagesMDC PT ChartKailas NimbalkarNo ratings yet

- Simplified Concrete Modeling: Mat - Concrete - Damage - Rel3Document14 pagesSimplified Concrete Modeling: Mat - Concrete - Damage - Rel3amarNo ratings yet

- A Study On Effective Training Programmes in Auto Mobile IndustryDocument7 pagesA Study On Effective Training Programmes in Auto Mobile IndustrySAURABH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Mutual Fund Insight Nov 2022Document214 pagesMutual Fund Insight Nov 2022Sonic LabelsNo ratings yet

- NYLJtuesday BDocument28 pagesNYLJtuesday BPhilip Scofield50% (2)

- MSDS Bisoprolol Fumarate Tablets (Greenstone LLC) (EN)Document10 pagesMSDS Bisoprolol Fumarate Tablets (Greenstone LLC) (EN)ANNaNo ratings yet

- Software Hackathon Problem StatementsDocument2 pagesSoftware Hackathon Problem StatementsLinusNelson100% (2)

- National Senior Certificate: Grade 12Document13 pagesNational Senior Certificate: Grade 12Marco Carminé SpidalieriNo ratings yet

- Mayor Breanna Lungo-Koehn StatementDocument2 pagesMayor Breanna Lungo-Koehn StatementNell CoakleyNo ratings yet

- 0901b8038042b661 PDFDocument8 pages0901b8038042b661 PDFWaqasAhmedNo ratings yet

- Ap06 - Ev04 Taller en Idioma Inglés Sobre Sistema de DistribuciónDocument9 pagesAp06 - Ev04 Taller en Idioma Inglés Sobre Sistema de DistribuciónJenny Lozano Charry50% (2)

- RFM How To Automatically Segment Customers Using Purchase Data and A Few Lines of PythonDocument8 pagesRFM How To Automatically Segment Customers Using Purchase Data and A Few Lines of PythonSteven MoietNo ratings yet

- Org ChartDocument1 pageOrg Chart2021-101781No ratings yet

- MOL Breaker 20 TonDocument1 pageMOL Breaker 20 Tonaprel jakNo ratings yet

- Nguyen Dang Bao Tran - s3801633 - Assignment 1 Business Report - BAFI3184 Business FinanceDocument14 pagesNguyen Dang Bao Tran - s3801633 - Assignment 1 Business Report - BAFI3184 Business FinanceNgọc MaiNo ratings yet

- SCHEDULE OF FEES - FinalDocument1 pageSCHEDULE OF FEES - FinalAbhishek SunaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Radar Warning ReceiverDocument23 pagesIntroduction To Radar Warning ReceiverPobitra Chele100% (1)

- Elb v2 ApiDocument180 pagesElb v2 ApikhalandharNo ratings yet

- Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS) : An Overview: Celia M. ReyesDocument28 pagesCommunity-Based Monitoring System (CBMS) : An Overview: Celia M. ReyesDiane Rose LacenaNo ratings yet

- Computerized AccountingDocument14 pagesComputerized Accountinglayyah2013No ratings yet

- Immovable Sale-Purchase (Land) ContractDocument6 pagesImmovable Sale-Purchase (Land) ContractMeta GoNo ratings yet

- Failure of A Gasket During A Hydrostatic TestDocument7 pagesFailure of A Gasket During A Hydrostatic TesthazopmanNo ratings yet

- Chapter03 - How To Retrieve Data From A Single TableDocument35 pagesChapter03 - How To Retrieve Data From A Single TableGML KillNo ratings yet

- Yamaha F200 Maintenance ScheduleDocument2 pagesYamaha F200 Maintenance ScheduleGrady SandersNo ratings yet

- Fast Binary Counters and Compressors Generated by Sorting NetworkDocument11 pagesFast Binary Counters and Compressors Generated by Sorting Networkpsathishkumar1232544No ratings yet

- 7373 16038 1 PBDocument11 pages7373 16038 1 PBkedairekarl UNHASNo ratings yet

- Province of Camarines Sur vs. CADocument8 pagesProvince of Camarines Sur vs. CACrisDBNo ratings yet

- Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowFrom EverandHeretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (57)

- The Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpFrom EverandThe Russia Hoax: The Illicit Scheme to Clear Hillary Clinton and Frame Donald TrumpRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaFrom EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- The Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteFrom EverandThe Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You VoteRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- The Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Free: Florida's Blueprint for America's RevivalNo ratings yet

- Thomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaFrom EverandThomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (107)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentFrom EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- The Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaFrom EverandThe Shadow War: Inside Russia's and China's Secret Operations to Defeat AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesFrom EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesNo ratings yet

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)

- Crimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963From EverandCrimes and Cover-ups in American Politics: 1776-1963Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismFrom EverandThe Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political TribalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- Modern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesFrom EverandModern Warriors: Real Stories from Real HeroesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeFrom EverandGame Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a LifetimeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (572)

- The Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldFrom EverandThe Great Gasbag: An A–Z Study Guide to Surviving Trump WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- The Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaFrom EverandThe Deep State: How an Army of Bureaucrats Protected Barack Obama and Is Working to Destroy the Trump AgendaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- No Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesFrom EverandNo Mission Is Impossible: The Death-Defying Missions of the Israeli Special ForcesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Confidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentFrom EverandConfidence Men: Wall Street, Washington, and the Education of a PresidentRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (52)

- Kilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsFrom EverandKilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Socialism 101: From the Bolsheviks and Karl Marx to Universal Healthcare and the Democratic Socialists, Everything You Need to Know about SocialismFrom EverandSocialism 101: From the Bolsheviks and Karl Marx to Universal Healthcare and the Democratic Socialists, Everything You Need to Know about SocialismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Commander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943From EverandCommander In Chief: FDR's Battle with Churchill, 1943Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- Power Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicFrom EverandPower Grab: The Liberal Scheme to Undermine Trump, the GOP, and Our RepublicNo ratings yet

- The Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorFrom EverandThe Magnificent Medills: The McCormick-Patterson Dynasty: America's Royal Family of Journalism During a Century of Turbulent SplendorNo ratings yet