Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AFP v. Morel - Getty/AFP Motion For Summary Judgment

Uploaded by

Venkat BalasubramaniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AFP v. Morel - Getty/AFP Motion For Summary Judgment

Uploaded by

Venkat BalasubramaniCopyright:

Available Formats

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - X AGENCE FRANCE PRESSE,

: Plaintiff, - against DANIEL MOREL, Defendant and Counterclaim-Plaintiff. - against AGENCE FRANCE PRESSE, Counterclaim-Defendant, - and GETTY IMAGES (US), INC.; THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY and AFP and GETTY Licensees Does 1-et al., : : : : : : : : : : : : :

Filed 04/27/12 Page 1 of 58

10 Civ. 2730 (AJN)(MHD)

Third-Party Defendants. : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - X COUNTERCLAIM DEFENDANTS JOINT MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Joshua J. Kaufman Meaghan H. Kent Elissa B. Reese VENABLE LLP 575 7th Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20004-1601 Telephone: (202) 344-4000 Fax: (202) 344-8300 Counsel for Plaintiff-Counterclaim Defendant Agence France Presse

James Rosenfeld Deborah Adler Samuel M. Bayard DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP 1633 Broadway 27th floor New York, New York 10019 Telephone: (212) 489-8230 Attorneys for Counterclaim Defendants Getty Images (US), Inc. and The Washington Post Company

April 27, 2012

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 2 of 58

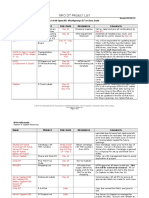

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities .................................................................................................................... -iiiPreliminary Statement ..................................................................................................................... 1 Legal Standard for Summary Judgment ......................................................................................... 5 AFPS ARGUMENTS .................................................................................................................... 6

1. The Twitter/TwitPic Terms of Service Provide a Copyright License.............................................. 6

GETTY IMAGES ARGUMENTS .............................................................................................. 12

2. A. B. C. D. E. The DMCA Protects Getty Images From Liability For Copyright Infringement .......................... 12 The 512(c) Safe Harbor............................................................................................................ 13 Getty Images Is a Service Provider. ............................................................................................ 13 Getty Images Stores Material On Its System At the Direction of Users. .................................... 14 Getty Images Did Not Have Actual or Constructive Knowledge That AFP Uploaded the Photos at Issue, and It Removed The Images As Soon As It Became Aware of Them. ........................ 16 Getty Images Did Not Receive a Financial Benefit Directly Attributable to the Infringing Activity or Have the Right and Ability to Control Such Activity. ............................................. 22 Getty Images Satisfied All of the Technical Requirements of the Statute ................................. 24 Mr. Morel Is Not Entitled to Any Relief on His Copyright Claims ............................................ 25 Getty Images Cannot Be Held Directly Liable For Copyright Infringement Because It Did Not Engage In Any Volitional Conduct................................................................................................ 26

F. G. 3.

DEFENDANTS JOINT ARGUMENTS ..................................................................................... 29

4. 5. 6. 7. Mr. Morels Claim for Indirect Liability Must Fail ....................................................................... 29 Mr. Morels Copyright Management Information Claims Must Fail ............................................ 35 The Defendants Did Not Act Willfully. ......................................................................................... 41 Mr. Morel Is Limited To A Single Statutory Damages Award For Each Of The Allegedly Infringed Works. ............................................................................................................................ 45

i

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 3 of 58

A. B.

Mr. Morel Is Limited to a Single Statutory Damages Award for Each Work for Which Defendants Are Jointly and Severally Liable. ............................................................................ 46 Mr. Morel Cannot Recover Multiple Statutory Damages Awards Against AFP or Getty Images Based on Licensees Actions. ..................................................................................................... 47

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................. 50

ii

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 4 of 58

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s) CASES AFP v. Morel, 769 F. Supp. 2d 295 (S.D.N.Y. 2011)......................................................................................37 Alling v. Universal Mfg. Corp., 5 Cal. App. 4th 1412 (Cal. Ct. App. 1992) ................................................................................8 Arista Records LLC v. Lime Group LLC, 784 F. Supp. 2d 313 (S.D.N.Y. 2011).............................................................................. passim Bouchat v. Champion Prods., Inc., 327 F. Supp. 2d 537 (D. Md. 2003, affd, 506 F.3d 315, 32931 (4th Cir. 2007)........................................................................................................46, 47, 48, 49 Bourne v. Walt Disney Co., 68 F.3d 621 (2d Cir. 1995).....................................................................................................6, 9 Capitol Records, Inc. v. MP3tunes, LLC, 821 F.Supp.2d 627 101 U.S.P.Q.2d 1093 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) ............................................ passim Cartoon Network LP, LLLP v. CSC Holdings, Inc., 536 F.3d 121 (2nd Cir. 2008).......................................................................................26, 27, 28 Castle Rock Entmt v. Carol Publg Grp., Inc., 955 F. Supp. 260 (S.D.N.Y. 1997), affd, 150 F.3d 132 (2d Cir. 1998) . No ..........................43 Columbia Pictures Television v. Krypton Broad. of Birmingham, Inc., 106 F.3d 284 (9th Cir. 1997), revd on other grounds sub nom. Feltner v. Columbia Pictures Television, Inc., 523 U.S. 340 (1998) ..................................................................48, 49 Commander Oil Corp. v. Advance Food Serv. Equip., 991 F.2d 49 (2d Cir. 1993).........................................................................................................7 Corbis, Corp. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 351 F.Supp.2d 1090 (W.D. Wash. 2004).....................................................................17, 20, 24 CoStar Group, Inc. v. LoopNet, Inc., 373 F.3d 544 (4th Cir. 2004) ....................................................................................................26 Danone Asia Pte. v. Happy Dragon Wholesale, Inc., No. 05 Civ. 1611, 2006 WL 845573 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 29, 2006) .............................................44 Demetriades v. Kaufmann, 690 F. Supp. 289 (S.D.N.Y. 1988) ..........................................................................................30

iii

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 5 of 58

Fallaci v. New Gazette Literary Corp., 568 F. Supp. 1172 (S.D.N.Y. 1983).........................................................................................42 Fitzgerald Publg Co. v. Baylor Publg Co., 807 F.2d 1110 (2d Cir. 1986)...................................................................................................42 Flava Works, Inc. v. Gunter, No. 10 C 6517, 2011 WL 1791557 (N.D. Ill., May 10, 2011) ................................................26 Generale Bank v. Czarnikow-Rionda Sugar Trading, Inc., 47 F. Supp. 2d 477 (S.D.N.Y. 1999)..........................................................................................7 Gershwin Publg Corp. v. Columbia Artists Mgmt., Inc., 443 F.2d 1159 (2d Cir. 1971)...................................................................................................30 GMA Accessories, Inc. v. Eminent, Inc., No. 07 Civ. 3219, 2008 WL 2355826 (S.D.N.Y May 29, 2008) .............................................26 Hamil Am. Inc. v. GFI, 193 F.3d 92 (2d Cir. 1999).......................................................................................................42 In re Aimster Copyright Litigation, 252 F.Supp.2d 634 (N.D. Ill. 2002) .........................................................................................14 Io Group, Inc. v. Veoh Networks, Inc., 586 F.Supp.2d 1132 (N.D. Cal. 2008) ............................................................................. passim Livnat v. Lavi, No. 96 Civ 4967, 1998 WL 43221 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 2, 1998) ...................................................30 Lumbermens Mut. Cas. Ins. Co. v. Darel Grp. U.S.A., Inc., 253 F. Supp. 2d 578 (S.D.N.Y. 2003)........................................................................................5 Lyons Pship, L.P. v. Morris Costumes, Inc., 243 F.3d 789 (4th Cir. 2001) ...................................................................................................44 Martin v. City of Indianapolis, 192 F.3d 608 (7th Cir. 1999) ..............................................................................................43, 44 Marvullo v. Gruner & Jahr, 105 F. Supp. 2d 225 (S.D.N.Y. 2000)......................................................................................31 Matthew Bender & Co. v. West Publg Co., 158 F.3d 693 (2d Cir. 1998).....................................................................................................30 McClatchey v. Associated Press, No. 3:05-cv-145, 2007 WL 1630261 (W.D. Pa. June 4, 2007) ....................................... passim

iv

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 6 of 58

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005) .................................................................................................................30 Orderline Wholesale Distrib., Inc., v. Gibbons, 675 F. Supp. 122 (S.D.N.Y. 1987) ............................................................................................6 People v. Harris, Case No. 2011-N.Y.-080152 (April 20, 2011) ....................................................................7, 11 Perfect 10, Inc. v. CCBill LLC, 488 F.3d 1102 (9th Cir. 2007) ...........................................................................................14, 21 Principal Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Vars, Pave, McCord & Freedman, 77 Cal. Rptr. 2d 479 (Cal. Ct. App. 1998) .................................................................................8 Rosen v. Hosting Services, Inc., 771 F.Supp.2d 1219 (C.D. Cal. 2010) .....................................................................................14 U.S. Media Corp. v. Edde Entmt Corp., No. 94 Civ. 4849, 1998 WL 401532 (S.D.N.Y. July 17, 1998) ..............................................46 UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Veoh Networks, Inc., 620 F.Supp.2d 1081 (C.D. Cal. 2008) (UMG I) ...................................................................15 UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Veoh Networks, Inc., 665 F.Supp.2d 1099 (C.D. Cal. 2004) (UMG II) ...............................................19, 20, 21, 22 Viacom Intern., Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., 718 F.Supp.2d 514 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), affd in part, vacated in part, Viacom Intl, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., -- F.3d --, Nos. 10-3270-cv, 10-3342-cv, 2012 WL 1130851 (2d Cir. Apr. 5, 2012)....................................................................................................... passim Walt Disney Co. v. Powell, 897 F.2d 565 (D.C. Cir. 1990) .................................................................................................46 Wolk v. Kodack Imaging Network, Inc., --- F.Supp.2d. ---, No. 10 Civ. 4135, 2012 WL 11270 (Jan. 3, 2012, S.D.N.Y. 2012) ....................................................27, 28, 29, 34 Wolk v. Kodak Imaging Network, Inc., No. 10 Civ. 4135(RWS), 2011 WL 940056 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 17, 2011) .......................... passim STATUTES 17 U.S.C. 504(c)(1) ...................................................................................................45, 46, 47, 48 17 U.S.C. 504(c)(2) ......................................................................................................................41

v

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 7 of 58

17 U.S.C. 512 ...................................................................................................................... passim 17 U.S.C. 1202(a) .....................................................................................................35, 36, 37, 40 17 U.S.C. 1202(b) .................................................................................................................35, 40 OTHER AUTHORITIES 3 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright 12.04[A][3][b][i] (2006) ..........................................................................................................................17, 29, 49 4 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright 14.04[B][3][a] (2010)...........42 Copyright Infringement Liability of Online and Internet Service Providers: Hearing Before the S. Judiciary Committee on S. 1146, S. Hrg. 105-366, Sept. 4, 1997 at 2...............14 Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 .............................................................................................................................6 Fed. R. Civ. P. 56 .............................................................................................................................5 Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d)(2)..................................................................................................................26 Restatement (2d) Contracts 202(2) (1981) ...................................................................................7 S. Rep. No. 105-190, 1998 WL 239623 (Leg.Hist.) (1998) ..........................................................13

vi

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 8 of 58

Pursuant to the Courts Order and Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 56, Counterclaim Defendants Agence France Presse (AFP), Getty Images (US), Inc. (Getty Images) and The Washington Post Company (the Post) (collectively Defendants) submit this memorandum of law in support of their joint motion for summary judgment as to the remaining count of the Complaint and the Counterclaims asserted by Counterclaim Plaintiff Daniel Morel (Morel). Preliminary Statement On January 12, 2010, a devastating earthquake struck Haiti. Morel, a Haitian photographer, took photos of the destruction in Port-au-Prince. He found internet access at his hotel and posted his photos on the social media network Twitter in high resolution, without any copyright notices, restrictions or limitations on use of any kind. The Twitter Terms of Service anticipate, encourage, and provide a license for the rebroadcast of messages and images by other Twitter users and broadcasters. AFP, an international newswire service, covers news around the world. When the Haitian earthquake occurred, it distributed news and images of the earthquake through its media subscribers and customers. While it was trying to ascertain the condition of its own employees and contractors in Haiti, one of its photo editors found pictures of the Haitian earthquake on Twitter/TwitPic by Lisandro Suero (Suero). On Sueros TwitPic page there were no restrictions on use, no copyright notices and no limitations of any kind. The AFP editor believed that these pictures, like so many other pictures posted to social media during political upheavals (e.g. the Arab Spring, the Syrian massacres, demonstrations in Iran) and in the aftermath of natural disasters, had been taken by citizen journalists spreading the word about the breaking news events they had witnessed and captured in photos and videos. With this understanding,

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 9 of 58

AFP downloaded eight of Morels photos from the Suero page (Photos at Issue) believing that they were Sueros photos, posted with the intent that they be distributed and distributed them to its news subscribers. Getty Images, one of the worlds leading providers of high-quality news and editorial photos, is AFPs distribution partner. As a result of AFP putting the Photos at Issue out on its wire, the photos were provided to Getty Images subscribers via its news feed and, at the same time, posted to Getty Images website. Getty Images does not pre-screen, review, edit or alter images it receives from AFP, and they are distributed to customers either through an FTP feed or through a self-service online system. AFP transmits hundreds of thousands of photos a year in this manner on its own wire and onto the Getty Images wire and website. The transmission of content through Getty Images and AFPs feeds is virtually instantaneous, allowing customers immediate access to breaking news imagery. After it distributed the Photos at Issue, AFP determined, based on discrepancies in other photos obtained from Sueros Twitter/TwitPic page, that Suero was not the photographer of the photos for which he had taken credit; Morel was. AFP believed Morel posted the photos to Twitter, as thousands of others have done on social networks, to alert the world as to the conditions surrounding them. AFP immediately posted a credit change on its website and sent a credit change notification via its wire to all its subscribers, indicating that the photos should be credited to Morel. As a result of the credit change, the Suero-credited photos on the AFP website were automatically deleted and replaced by the Morel-credited photos. In the process of correcting the photographer credit, AFP also transmitted the properly credited photos to Getty Images back-end system through its feed. The corrections were pushed to Getty Images editorial subscription feed customers at the same time. Unfortunately, AFPs posting of new

2

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 10 of 58

Morel-credited photos did not automatically delete and replace the original Suero-credited photos on the Getty Images website (unlike on the AFP site), so multiple sets of the photos remained in the Getty Images system and on its website. This was not known to AFP or Getty Images until a few weeks later. On January 13, 2010, Getty Images received notice from Corbis Images (Corbis), claiming that Morel was a professional photographer with whom it had a contract. Corbis claimed it had the exclusive rights to Morels Haiti photos and demanded that Getty Images and AFP stop offering Morels Haiti photos to the public. AFP and Getty Images promptly removed all photos of the earthquake attributed to Daniel Morel. On February 2, 2010, Corbis contacted Getty Images again, indicating that Morels earthquake photos remained on its website. Getty Images investigated and, for the first time, learned that the Suero-credited photos were still available. Getty Images had not known that when AFP issued the caption correction, it had not removed the Suero-credited photos from the Getty Images site; Getty Images then immediately removed them. From this point, no Photos at Issue remained available for licensing on Getty Images website. Subsequently, Morel, through his counsel, sent out cease and desist letters to the Defendants and various third-party publishers of the photos. AFP filed for declaratory judgment, seeking the courts guidance on whether its actions constituted an infringement. Morel then filed his counterclaim against AFP, Getty Images and others (some of whom have since been dismissed) for copyright infringement, DMCA and Lanham Act violations. Morels Lanham Act claims were summarily dismissed on a Motion to Dismiss under rule 12(b)(6). The Post was one of the Getty Images licensees that had posted certain of the Photos at Issue on its website immediately after the earthquake. In the Posts photo management system at

3

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 11 of 58

the time, kill notices appeared on screen and then disappeared as new assets came through the feed. Accordingly, no one in the Posts Photo Department saw AFPs January 14 kill notice. On June 10, 2010, Getty Images informed the Post that three of the Photos at Issue appeared in an online photo gallery were the subject of a copyright dispute, and should be removed. The Posts photo editors promptly acted to remove the photos and believed that the photos had been successfully removed. Unknown to the Post, Morels counsel had separately been attempting to contact the Post about these photos with misdirected correspondence. A few days later, Morels counsel sent a letter threatening to add the Post to the lawsuit. Upon receiving this letter (the first to reach a Post recipient), in-house counsel for the Post emailed Morels counsel, asking Morel to refrain from suing the Post until the parties had spoken, and requesting information to help identify the photos about which Morel was complaining. The Post never received a response. Believing that it had successfully removed the photos as requested by Getty Images (a belief reinforced by the lack of a response to the Posts email to Morels counsel), the Post did not learn about any problem with the photos removal until April 6, 2011, when Getty Images outside counsel informed the Post that the three Photos at Issue remained available on the online photo gallery. The apparent reappearance, or continued availability, of these photos was unintentional, and the Post immediately removed the photos once again. Dissatisfied with the Posts actions regarding the photos, Morel added the Post as a Counterclaim Defendant. The three remaining Defendants AFP, Getty Images and the Post now seek to have Morels remaining claims summarily dismissed. AFP moves for summary judgment as to Morels copyright infringement claims pursuant to the license Morel provided to use his photos when he posted them on Twitter (Point 1). Getty Images moves for dismissal of all copyright claims based on the Digital Millennium Copyright Acts (DMCA) safe harbor protecting on4

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 12 of 58

line service providers from liability for third-party content (Point 2), and alternatively argues that it did not engage in sufficient volitional conduct to be held directly liable for infringement (Point 3). AFP and Getty Images both move for the dismissal of claims asserting contributory liability as to them, based on (a) their lack of actual or constructive knowledge that the images were infringing when they licensed them to customers, and (b) their lack of substantial participation in the infringement; and Getty Images, the sole party charged with vicarious infringement, asserts that none of the elements have been adequately established, nor are there any factual issues which preclude summary judgment (Point 4). All Defendants submit that Morel has failed to adequately establish the DMCA 1202 claims for summary judgment purposes, both because they did not provide false Copyright Management Information (CMI) with the requisite intent to impose liability, and because they did not remove any CMI (Point 5). Moreover, all Defendants assert that even if the Court finds copyright infringement, it should nonetheless hold that Morel has failed to establish willfulness, and thus there is no basis for enhanced statutory damages (Point 6); nor may Morel seek multiple statutory damages awards for each of the works at issue (Point 7). 1 Legal Standard for Summary Judgment Summary judgment is appropriate where there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Fed. R. Civ. P. 56. A party may not survive summary judgment by relying on merely conclusory allegations or unsubstantiated speculation. See Lumbermens Mut. Cas. Ins. Co. v. Darel Grp. U.S.A., Inc., 253 F. Supp. 2d 578, 581 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (quoting Scotto v. Almenas, 143 F.3d 105, 114 (2d Cir. 1998)). A court must view the evidence presented through the prism of the substantive evidentiary

All of Morels remaining claims have either been dismissed on Defendants motion to dismiss (Counterclaims 6 and 7) or were asserted against parties who have been dismissed (Counterclaims 8, 9 and 10).

1

5

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 13 of 58

burden. Orderline Wholesale Distrib., Inc., v. Gibbons, 675 F. Supp. 122, 129 (S.D.N.Y. 1987) (quoting Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 254 (1986)). AFPS ARGUMENTS 2 1. The Twitter/TwitPic Terms of Service Provide a Copyright License. AFP moves for summary judgment against Morels copyright infringement claims based on the complete defense of license. Morel was in Haiti on January 12, 2010, when the earthquake struck. (56.1 Stmt. 71). He took photos of the aftermath, signed up for a Twitter account, and uploaded several photos via TwitPic, a photo sharing Twitter application. (56.1 Stmt. 72, 75, 81). By registering for a Twitter account and posting his photos via TwitPic, Morel became subject to the Twitter Terms of Service that granted a license to third parties, including the Defendants and their subscribers, to rebroadcast his photos. (56.1 Stmt. 84, 85). A license is a complete defense to a claim of copyright infringement. Bourne v. Walt Disney Co., 68 F.3d 621, 63132 (2d Cir. 1995). The burden of proving the existence of a license is on the party claiming its protection, but where the scope of the license is at issue, the copyright owner bears the burden of proving that the defendants copying was unauthorized. Id. at 631. Here, the Court has found a license to exist (Doc. 52, pp. 11), and it is the scope of that license that is at issue. Therefore, the burden is on Morel to prove that the Defendants do not fall within the license to Twitters other users, as provided by the Twitter Terms of Service.

AFP indicated to the Court that it intended to move for summary judgment that Mr. Morel lacked standing as to his copyright claims because pursuant to the terms of his contract with his licensing agent, Corbis, he had upon submitting the photographs at issue in this case, transferred the exclusive right to enforce his copyrights to Corbis. After AFP raised this issue, Mr. Morel apparently in recognition of the fact he did not have the rights to pursue this cause of action, approached Corbis in regard to the assignment of his enforcement rights. As a result, Corbis on April 6, 2012 transferred the right to enforce the copyrights at issue in this case to Mr. Morel (see letter of April 9, 2012 attached hereto as Exhibit 1). AFP will therefore not move for summary judgment on this issue at this time, but does intend to raise the issue of Mr. Morel proceeding with this litigation for two years without proper standing, at the appropriate juncture, most likely pursuant to a Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 Motion.

6

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 14 of 58

The Twitter Terms of Service are applicable by virtue of Morels use of Twitter and TwitPic. Though TwitPic has its own Terms of Service, Twitter and TwitPic are interrelated and their respective Terms of Service must be read together. See Commander Oil Corp. v. Advance Food Serv. Equip., 991 F.2d 49, 5253 (2d Cir. 1993); see also Generale Bank v. CzarnikowRionda Sugar Trading, Inc., 47 F. Supp. 2d 477, 481 (S.D.N.Y. 1999) ([T]he two documents are interrelated and co-dependent, and in such circumstances New York contract law holds that documents should be read and interpreted together); Restatement (2d) Contracts 202(2) (1981) (A writing is interpreted as a whole, and all writings that are part of the same transaction are interpreted together.). TwitPic is an application for use in conjunction only with Twitter that allows users to share photos and videos. (56.1 Stmt. 76, 77). To post photos on TwitPic, a user must first register for a Twitter account. (56.1 Stmt. 78). When a user attempts to login to TwitPic, the user is transferred to a Twitter page to complete the login, where the user is provided with the specific notice that you continue to operate under Twitters Terms of Service. (56.1 Stmt. 80). When Morel set up his Twitter account on January 12, 2010, he saw and accepted the Twitter Terms of Service. (56.1 Stmt. 82). In order to register for a Twitter account and use the service, the user, namely Morel, must click on a button below a text box that displays Twitters Terms of Service. (56.1 Stmt. 83). By clicking on the button, the user agrees to Twitters Terms of Service. (Id.); see also People v. Harris, Case No. 2011-N.Y.080152, *2 (April 20, 2011) (attached hereto at Exhibit 2). When evaluating this issue on Defendants Motion to Dismiss, Judge Pauley applied the Twitter Terms of Service. (Dkt. 52, p. 10). The relationship between Twitter and TwitPic is universally understood, as demonstrated by Morel himself and his agents; in Corbis letters to Getty Images and AFP they refer to Morels photos on his Twitter account as did Morel in his initial Counterclaim (56.1 Stmt 188,

7

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 15 of 58

Cameron Decl., Ex. C; see also Dkt. 4, p. 18 and Twitter Terms of Service referred to and attached as Ex. A thereto). Pursuant to the Twitter Terms of Service, Morel granted a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license, to use, copy, publish, display, and distribute posted materials to three categories of users: Twitter, Twitters partners, and Twitters other users. (56.1 Stmt. 84, 85). Specifically, the Twitter Terms of Service state: By submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods (now known or later developed). Tip: This license is you authorizing us to make your tweets available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same. But whats yours is yours you own your content. ... You are responsible for your use of the Services, for any Content you provide, and for any consequences thereof, including the use of your Content by other users and our third party partners. (56.1 Stmt. 85) (emphasis added). As a third-party beneficiary, AFP may enforce the terms of the license as provided by the Twitter Terms of Service. The Twitter Terms of Service are governed by California law. (56.1 Stmt. 88). California law permits third-party beneficiaries to enforce the terms of a contract made for their benefit. Principal Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Vars, Pave, McCord & Freedman, 77 Cal. Rptr. 2d 479, 488 (Cal. Ct. App. 1998). To establish third party beneficiary status, a party carries the burden of proving that the contracting parties intended purpose in executing their agreement was to confer a direct benefit on the alleged third party beneficiary. Alling v. Universal Mfg. Corp., 5 Cal. App. 4th 1412, 1439-40 (Cal. Ct. App. 1992). It is not necessary that the intent to benefit the third party be manifested by the promisor; it is sufficient that the promisor understand that the promisee has such intent. Id. at 1440. Therefore, we look to whether Twitter intended the license provided by its Terms of Service to benefit its other users.

8

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 16 of 58

AFP has already met the burden of proving the existence of a license, and Morel now has the burden to show that the scope of the license does not include other users such as Defendants and their licensees, which he cannot do. See Bourne, 68 F.3d at 631. The Courts Order on Defendants Motion to Dismiss held that Twitters Terms of Service necessarily require[d] Morel as promisor to confer certain rights of use on two classes Twitters partners and sublicensees and that it could not find on the pleadings that it conferred a license to other users. (Dkt. 52, p. 12, emphasis added). Looking now beyond the pleadings, as the Court may do at this juncture, the evidence shows that Twitters understood intent is to grant a license to other users. Twitters intent to license to other users beyond just itself and its third party partners is evidenced by its Terms of Service, which state, You are responsible for your use of the Services, for any Content you provide, and for any consequences thereof, including the use of your Content by other users and our third party partners. (56.1 Stmt. 85, 86) (emphasis added). This language indicates three classes of users: Twitter, its partners, and other users. This intent is further evidenced by Twitters statement in its Terms of Service that it encourage[s] and permit[s] broad re-use of content that is posted on Twitter. (56.1 Stmt. 87). Twitter unambiguously provides that AFP is covered by other users in its Guidelines for Third Party Use of Tweets in Broadcast or Other Off line Media (Guidelines) (56.1 Stmt. 91; Hendon Decl. 7, Ex. 5). In its Guidelines, Twitter not only allows but encourages the reuse of Twitter postings, including Tweets, Usernames, Hashtags and Images, stating [w]e welcome and encourage the use of Twitter in broadcast. (56.1 Stmt. 89). The Guidelines even provide suggestions to third party news entities (like AFP) on how to get the most out of using Tweets in their broadcasts. (56.1 Stmt. 90). Under the Additional Information section

9

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 17 of 58

of its Guidelines, Twitter provides a broad and all-encompassing definition of broadcast and offline media: What do you mean by broadcast or other offline media? Broadcast includes but is not limited to: the exhibition, distribution, transmission, reproduction, public performance or public display of Tweets by any and all means of media delivery (all forms of television, satellite, internet protocols, video, closed-circuit wireless, and electronic sell through, etc.) whether existing now or hereafter developed (56.1 Stmt. 91). The proclamation of Twitters Terms of Service and Guidelines that the entire purpose of Twitter is that Twitters other users are permitted and encouraged to broadly re-broadcast posted content is widely understood by Twitter users. This is evidenced every day by the uncountable number of daily re-tweets on Twitter and in the media where Twitter/TwitPic posts are copied, reprinted, quoted, and rebroadcast by third parties. (56.1 Stmt. 93, 94; see examples and articles at Hendon Dec., Exs. 6, 7). AFP is just one of the hundreds of thousands of Twitters other users who rebroadcast Twitter/TwitPic posts every day with no other permission than Twitters Terms of Service. (56.1 Stmt. 93; Hendon Dec., Ex. 7). Twitter/TwitPic make clear, and Twitter/TwitPic users understand, that Twitter/TwitPic postings will be publicly available and broadly re-distributed through the internet and other media. (56.1 Stmt. 85, 93, 94; see specifically, Tip[:] What you say on Twitter may be viewed all around the world instantly. You are what you Tweet! and This license is you authorizing us to make your tweets available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same.)(emphasis added). Indeed, many Twitter/TwitPic users post to the service for the purpose of broadly disseminating their posted material and to be re-Tweeted or rebroadcast because it increases their social media influence or clout. (56.1 Stmt. 94; see articles at Hendon Decl. 8, Ex. 6).

10

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 18 of 58

This understood intent that Twitter is to be used to share content was recently confirmed by the Criminal Court of the City of New York in The People of the State of New York v. Harris. Case No. 2011-N.Y.-080152, *2 (April 20, 2011) (attached hereto at Exhibit 2). There, though reviewing a motion to quash a criminal subpoena on privacy grounds, the court, referencing Twitters Terms of Service and Privacy Policy, explained Twitters understood purpose: By design, Twitter has an open method of communication. It allows its users to quickly broadcast up-to-the-second information around the world. The Content you submit, post, or display will be able to be viewed by other users of the Services and through third party services and websites. The size of the potential viewing audience and the time it can take to reach that audience is also no secret, as the Terms [of Service] go on to disclose: What you say on Twitter may be viewed all around the world instantly [t]his license is you authorizing us to make your Tweets available to the rest of the world and let others do the same. [Twitter] is primarily designed to help you share information with the world Id. at *2-3 (emphasis added and internal citations excluded). The court even noted that Twitter has also become the way that many receive their news information. Id. at FN 3. As described above, it is understood that Twitter/TwitPic is the medium for sharing content; not the medium for making proprietary sales. Morel was aware of Twitters purpose as evidenced by his statement that he posted his photos on Twitter/TwitPic in the hopes that his images would span the globe to inform the world of the disaster. (56.1 Stmt. 92). Had Morel truly wanted to engage in the proprietary distribution of his photos, he could have and should have sent his photos to his licensing agent Corbis, as he eventually did. (56.1 Stmt. 166). Morel admitted he knew of no professional photographer who sold their works through Twitter or used it to license their works. (56.1 Stmt. 97). Licensing of proprietary images can take place through a variety of other online venues, including licensing agents, such as Corbis, or private websites. Posting images of a natural disaster in high resolution, with no restriction, on a

11

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 19 of 58

social media outlet such as Twitter, where it is known and understood that materials are almost universally rebroadcast, simply cannot be allowed to be a mechanism for a gotcha cause of action. (see 56.1 Stmt. 95, 96). To hold otherwise would hold that retweeting is an infringing activity and would effectively shut down Twitter and other similar social media sites. As a matter of law, AFP and its licensees are third-party beneficiaries of the Twitter Terms of Service, agreed to by Morel, are covered by the license therein, and Morel cannot succeed on his claims for copyright infringement. AFP thus asserts that Defendants are thus entitled to summary judgment as to Counterclaims 1 and 11. GETTY IMAGES ARGUMENTS 2. The DMCA Protects Getty Images From Liability For Copyright Infringement The DMCA safe harbor protecting internet service providers from liability for third-party content, 17 U.S.C. 512(c), applies squarely here. AFP placed the Photos at Issue on Getty Images database with minimal involvement, oversight or knowledge on Getty Images part. During the short time the images were posted, the majority of its end-users licensed them through an almost entirely automated system. As soon as Getty Images became aware of the allegedly infringing images and was provided accurate information to enable it to correctly identify the images, it immediately took them down. Every single requirement of the safe harbor is satisfied here, immunizing Getty Images from liability for monetary and most forms of injunctive relief for direct and indirect copyright infringement. Imposing additional burdens would disregard the realities of the market and impede the great public and constitutional interest in the rapid distribution of news images. Moreover, even the limited forms of injunctive relief which the statute permits are unnecessary. The First, Second and Third Counterclaims should therefore be dismissed in their entirety as to Getty Images.

12

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 20 of 58

A. The 512(c) Safe Harbor Section 512(c) of the DMCA 3 protects service providers from liability for copyright infringement by reason of the storage at the direction of a user of material that resides on a system or network controlled or operated by or for the service provider, so long as the service provider satisfies both the specific requirements of 512(c) and the general requirements set by other provisions of 512. In sum, a party must meet the following requirements: 1. It must be a service provider, as defined in 512(k)(1)(B); 2. It must store material on its system at the direction of a user, 512(c); 3. It must (a) not have actual knowledge of the allegedly infringing materials on its site; (b) not be aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity was apparent; and (c) remove or disable access to the allegedly infringing material expeditiously when notified, 512(c)(1)(A) & 512(c)(1)(C); 4. It must not receive a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity, where it has the right and ability to control such activity, 512(c)(1)(B); and 5. It must satisfy the technical requirements of the statute: (a) designate an agent to receive notifications of infringement, 512(c)(2); (b) adopt and reasonably implement a policy to terminate repeat infringers, 512(i)(1)(A); and (c) not interfere with standard technical measures, 512(i)(1)(B). Getty Images meets every single one of these requirements. B. Getty Images Is a Service Provider. Section 512 defines service provider as a provider of online services or network access, or the operator of facilities therefor. 512(k)(1)(B). This definition encompasses a broad variety of internet activities. Wolk v. Kodak Imaging Network, Inc., No. 10 Civ. 4135(RWS), 2011 WL 940056, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 17, 2011) (site on which photographs are stored and shared was service provider). One court stated it would have trouble imagining

In enacting the DMCA, Congress recognized that merely carrying out their ordinary operations requires internet service providers to engage in all kinds of acts that expose them to potential copyright infringement liability, such as making electronic copies to store or transmit information, or directing users to third-party sites. [B]y limiting the liability of service providers, the DMCA ensures that the efficiency of the Internet will continue to improve and that the variety and quality of services on the Internet will continue to expand. S. Rep. No. 105-190, 1998 WL 239623 (Leg.Hist.) (1998) at 8. The Act therefore creates a series of safe harbors, for certain common activities of service providers. Id. at 19.

13

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 21 of 58

the existence of an online service that would not fall under the definition. In re Aimster Copyright Litigation, 252 F.Supp.2d 634, 658 (N.D. Ill. 2002). Getty Images, which stores, displays and licenses photos to users through its website (56.1 Stmt. 29-31), is obviously a provider of online services, 512(k)(1)(B), well within the statutory definition. C. Getty Images Stores Material On Its System At the Direction of Users. Getty Images fits the 512(c) safe harbor because it stores material on its system at the direction of its users. This breaks into three elements: First, AFP is a user of Getty Images system. The statute suggests a user is an entity that stores or transmits content on a service providers network, without defining the term. Given the broad definition of service provider discussed above, the law plainly contemplates just as broad a range of users of those providers services. The case law has applied the term both to content creators that store content on the servers or transmit content through the pipes of internet service providers seeking the safe harbor, e.g., Perfect 10, Inc. v. CCBill LLC, 488 F.3d 1102, 1117-18 (9th Cir. 2007) (assuming online publisher was user of webhosting service provider); Rosen v. Hosting Services, Inc., 771 F.Supp.2d 1219, 1221-22 (C.D. Cal. 2010) (assuming photographer was user of website-hosting service provider), and to customers of file-storing/sharing websites, e.g., Capitol Records, Inc. v. MP3tunes, LLC, 821 F.Supp.2d 627 101 U.S.P.Q.2d 1093, (S.D.N.Y. 2011). Analogous to these two categories are the image partners (like AFP) that provide content to Getty Images website and the customers (like NBC News and CNN) that license content from that site. 4

The legislative history suggests that providers of content for an online site offering audio or video are users of that site, Viacom Intern., Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., 718 F.Supp.2d 514, 520 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), affd in part, vacated in part, Viacom Intl, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., -- F.3d --, Nos. 10-3270-cv, 10-3342-cv, 2012 WL 1130851 (2d Cir. Apr. 5, 2012) indicating that providers of content for an online site offering photographs would be, too. See also Copyright Infringement Liability of Online and Internet Service Providers: Hearing Before the S. Judiciary Committee on S. 1146, S. Hrg. 105-366, Sept. 4, 1997 at 2 (For example, it might be said that a service provider

14

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 22 of 58

Second, Getty Images stores material on its system. (56.1 Stmt. 30). Furthermore, 512(c)s limitation of liability applies to alleged infringement by reason of the storage of materials at the direction of a user meaning that it protects not just a providers storage of material but any other functions carried out to facilitate[e] access to user-stored material. Viacom Intl, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., -- F.3d --, Nos. 10-3270-cv, 10-3342-cv, 2012 WL 1130851, at *14 (2d Cir. Apr. 5, 2012); UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Veoh Networks, Inc., 620 F.Supp.2d 1081, 1089 (C.D. Cal. 2008) (UMG I) ( 512(c) covers video-sharing service providers reproduction of works through automated creation of copies; public performance when users stream videos; and distribution of works when users download them). 5 AFP granted Getty Images a license to display, transmit and license its content through its feed systems and via its websites, necessitating storage of the content to facilitate these goals. (56.1 Stmt. 46-47). Getty Images display and transmission of third-party images such as AFPs facilitate access to the images. Finally, the Photos at Issue were put on Getty Images website at the direction of AFP and indeed, directly by AFP via transmission through its feed. AFP bore sole and complete responsibility for transmitting images to Getty Images system via the feed, which it did thousands of time a day without editing, modification or curation by Getty Images. (56.1 Stmt. 48-50). Getty Images did not participate in or supervise this process, and the only human

would be held liable for the unauthorized posting of copyrighted photographs on a Web site or electronic bulletin board residing on the service providers network, regardless of whether the service provider knew of the posting or exercised any sort of control over the content of the site.)(Open Statement of Sen. Hatch). 5 See also Wolk, 2011 WL 940056, at *3 (quoting Io Group, Inc. v. Veoh Networks, Inc., 586 F.Supp.2d 1132, 1147 (N.D. Cal. 2008)) (Section 512(c) was not intended by Congress to be limited to merely storing material, but was meant to encompass a broader range of services offered by internet companies.); Viacom, 718 F.Supp.2d at 526 (definition of service provider includes an entity offering the transmission, routing, or providing of connections for digital online communications, and thus this safe harbor plainly covers the provision of such services, access, and operation of facilitieswhen they flow from the materials placement on the providers system or network,); UMG I, 620 F.Supp.2d at 1089 (when content is displayed or distributed on Veoh it is as a result ofthe fact that users uploaded the content to Veohs servers to be accessed by other means and thus display/distribution is within the 512(c) safe harbor).

15

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 23 of 58

intervention on Getty Images part involved conforming image metadata entered by AFP to the Getty Images systems formatting conventions. (56.1 Stmt. 56). Nor does Getty Images lose the safe harbor because of automated functions it carries out after the files are loaded, like automatically adding standard licensing restrictions and credit detail, which are the same for all images transmitted by AFP. (See 56.1 Stmt. 52). Io Group, 586 F.Supp.2d at 1148 (video files are uploaded on Veoh through an automated process which is initiated entirely at the volition of Veohs users; Veoh does not lose the safe harbor through the automated creation of these files). D. Getty Images Did Not Have Actual or Constructive Knowledge That AFP Uploaded the Photos at Issue, and It Removed The Images As Soon As It Became Aware of Them. To avail itself of the 512(c) safe harbor, Getty Images must demonstrate that it (a) did not have actual knowledge of the allegedly infringing materials on its site; (b) was not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity was apparent; and (c) removed or disabled access to the allegedly infringing material expeditiously when notified, 512(c)(1)(A); see also 512(c)(1)(C). The Second Circuit recently affirmed that both actual knowledge and constructive knowledge (facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent) refer to knowledge of specific and identifiable infringements. Viacom, 2012 WL 1130851, at *5-6. Here, Getty Images had no actual knowledge and no reason to know about the allegedly infringing images until it received notice from Corbis, on two separate occasions, that certain categories of infringing images had been posted. On each of those occasions, Getty Images immediately removed the content from its website and referred the matter to AFP for resolution as the content provider.

16

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 24 of 58

1. Actual Knowledge Getty Images had no actual knowledge of infringement when AFP posted the Photos at Issue on its system through the automated feed process, and did not obtain any such knowledge before Corbis notified it by email (at which point, as discussed at 2.D.3. infra, Getty Images immediately took the images down). Morel makes a wholly conclusory allegation of knowledge but does not allege that he ever sent a DMCA takedown notice, or any type of notice, to Getty Images while the images were still on its website, nor does he provide any other evidence of actual knowledge thereby shifting the burden to himself to prove that Getty Images had knowledge of the allegedly infringing images during the period they were available. See 3 Nimmer 12B.04[A][3], n.41 ([A] service provider who offers competent testimony that it lacked actual knowledge shifts the burden of proof to the plaintiff to negate those claims. That last proof usually represents an insuperable hurdle for the plaintiff.); see Corbis, Corp. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 351 F.Supp.2d 1090, 1107 (W.D. Wash. 2004). He cannot satisfy this burden. The record contains no evidence whatsoever of actual knowledge just Getty Images testimony that it had none prior to contact from Corbis (56.1 Stmt. 159-60, 189, 214-15), and record evidence that AFP (i) did not advise Getty Images there was an issue with the photos credited to Morel until after they had been removed from Getty Images website; (ii) did not identify photos credited to Suero or mis-credited to David Morel as problematic; and (iii) sent through kill notices that did not tie to assets previously sent, preventing Getty Images from removing potentially infringing assets. (56.1 Stmt. 195, 203, 208, 212). 2. Constructive Knowledge (the Red Flag Standard) Nor did Getty Images have any awareness of any facts or circumstances from which infringing activity was apparent, 512(c)(1)(A)(ii). In assessing this factor:

17

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 25 of 58

the question is not what a reasonable person would have deduced given all the circumstances [but] whether the service provider deliberately proceeded in the face of blatant factors of which it was aware. In other words, apparent knowledge requires evidence that a service provider turned a blind eye to red flags of obvious infringement. Io Group, 586 F.Supp.2d at 1148 (citations and quotations omitted; emphasis added). Moreover, the red flags must point to specific instances of infringement. Viacom, 2012 WL 1130851, at *6. This Court has identified red flags where content comes from pirate sites which typically use words such as pirate, bootleg, or slang terms in their [URL] and header information but not where content comes from legitimate service providers. Viacom, 718 F.Supp.2d at 522; See also Capitol Records, 821 F. Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q., at 1104 (defendants file-sharing website did not take songs from sites which used words like pirate or bootleg, so defendant did not have red-flag knowledge of infringement). Getty Images received the images from AFP, a legitimate and long-trusted partner with a global reputation as a respected news agency, contractually obligated to provide content which is, to the best of its knowledge, non-infringing not from an anonymous or suspicious content provider, let alone a pirate operation. AFP provides Getty Images with hundreds of thousands of images per year, through a feed that Getty Images does not monitor. (56.1 Stmt. 48-50, 61). Unlike many other image partners that provide content, AFP has access to Getty Images backend system. It has been trained and authorized to place imagery directly onto Getty Images database, enter the relevant metadata with each image, edit that information or send corrections or kills, and remove images from the website. (56.1 Stmt. 60). Getty Images involvement with the distribution of AFP content is negligible and involves little or no human interaction: the content is provided through AFPs feed and both pushed through Getty Images news feed to customers and placed on Getty Images website as is, with automatically added licensing

18

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 26 of 58

restrictions and credit detail. (56.1 Stmt. 49-58). Customers can license that content on www.gettyimages.com through a self-service process with preset license agreements all without Getty Images involvement or knowledge. (56.1 Stmt. 59). Furthermore, Getty Images was not obligated to monitor AFPs content or check its own site for infringing activity, and any failure to do so does not constitute a red flag. The DMCA is explicit that safe harbor shall not be conditioned on a service provider monitoring its service or affirmatively seeking facts indicating infringing activity. Capitol Records, 821 F. Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q. at 1104 (quoting 512(m)(1)). Put another way, if investigation is required to determine whether material is infringing, then those facts and circumstances are not red flags a rule which makes sense where infringing works might be a small fraction of works posted to a website. Id. (emphasis added); UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Veoh Networks, Inc., 665 F.Supp.2d 1099, 1108 (C.D. Cal. 2004) (UMG II). The record demonstrates that through the course of Getty Images relationship with AFP, of the millions of images AFP provided, very few have ever been alleged to have been infringing and the few times there have been such allegations, AFP has addressed those issues fully in a manner that respected the terms of the Agreement. (56.1 Stmt. 62). Thus, Getty Images was not aware of any basis to (and did not) inquire about or investigate the copyright ownership of any of the Photos at Issue when AFP placed them on Getty Images system. (56.1 Stmt. 159). When Getty Images received notice from Corbis that images credited to Morel were infringing, it immediately took them down and promptly referred the matter to AFP for resolution. (56.1 Stmt. 188-92). The first time that anyone at Getty Images became aware that that AFP had transmitted Photos at Issue credited to Lisandro Suero to Getty Images, or that Photos at Issue credited to Suero were available on Getty Images website, was on February 2, 2010, when Corbis brought the issue to Getty Images

19

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 27 of 58

attention. (56.1 Stmt. 214). Prior to that, Getty Images had no obligation to pore through the millions of assets on its system to investigate whether infringement had occurred. Finally, even when Getty Images did receive notice from Corbis about the Photos at Issue, it was insufficient to put Getty Images on actual notice or even raise red flags (although Getty Images immediately removed the Photos at Issue when it received these emails). The initial notice from Corbis made no reference to content under the name Lisandro Suero or David Morel. Nor did it provide asset numbers. Rather, it merely referred to unidentified assets attributed to Daniel Morel the search term applied by Getty Images in immediate response to that notice. (56.1 Stmt. 188, 190-91). Under the exacting notice requirements of 512, 6 nonDMCA-compliant notice is not sufficient to give even constructive knowledge. 7 Here, Morel has alleged that (1) Corbis advised Getty Images by email on January 13, 2010 that Morel had uploaded some of his pictures from the earthquake in Haiti and put them on his Twitter page and that the images were then illegally copied and distributed to third parties, including Getty, (Cameron Decl. 13, Ex. C) after which Getty Images immediately

The statute provides that to be effective for purposes of 512(c), a notification of claimed infringement must be a written communication provide to the designated agent of a service provider that includes substantially the following: (i) a physical or electronic signature of an authorized signatory of the copyright owner; (ii) the allegedly infringed work; (iii) the allegedly infringing material and information reasonably sufficient to permit the service provider to locate this material; (iv) contact information for the complaining party; (v) a statement of the complaining partys good faith belief of infringement; and (vi) a statement that the notice is accurate and, under penalty of perjury, that the complaining party is authorized to act on behalf of the copyright owner. 512(c)(3)(A). Where a notice substantially complies with clauses (ii), (iii) and (iv) but not all of these requirements, the service provider promptly attempts to contact the complainant or otherwise takes reasonable steps to get substantially complying notice, and the provider is not able to obtain such notice, the notice cannot be considered in assessing actual or apparent knowledge. 512(c)(3)(B)(ii). 7 If a notice fails to substantially comply with certain of the required elements set forth in 512(c)(3)(A) (or substantially complies with three essential components but fails to substantially comply with all of the required elements upon request from the service provider), then the notification shall not be considered as a basis of either actual or constructive (red flag) knowledge. 512(c)(3)(B) (emphasis added). See Viacom, 718 F.Supp.2d at 52829 (even where Viacom identified the infringed works and the specific clips that infringed them, this was not sufficient to place YouTube on actual or apparent notice of other clips that infringed the same works); Wolk, 2011 WL 940056, at *4-5 (plaintiffs non-specific notices of infringement were insufficient to give photo-sharing site actual or apparent knowledge of infringement); UMG II, 665 F.Supp.2d at 1110 (identifying artist names was insufficient to require video-sharing site to search its database for those names in order to locate infringing material).

20

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 28 of 58

removed all images on its website credited to Morel; and (2) Corbis advised Getty Images by email on February 2, 2010 that certain additional assets duplicates of the Photos at Issue attributed to Lisandro Suero existed on the Getty Images website, after which Getty Images immediately removed all of those images from its website. (56.1 Stmt. 212-16, Cameron Decl. 22, Ex. F). However, these two notices did not satisfy the statutory requirements (or even enough of them to give constructive knowledge): (i) they did not come from and were not signed by the copyright owner or his authorized signatory (according to Morel) 8; (ii) they identified the allegedly infringed works only as Daniel Morel Haiti Images, which falls short of the statutes requirement that they be specifically identified 9; (iii) the first email did not provide the URL or other information reasonably sufficient to permit the service provider to locate this material 10; (iv) neither contained Morels contact information; and (v) neither contained a statement of the complaining partys good faith belief of infringement or (vi) a statement that the notice is accurate and, under penalty of perjury, the complaining party is authorized to act on behalf of the copyright owner. 11 Despite these deficiencies, in good faith and consistent with its respect for intellectual property rights, Getty Images took prompt and effective measures to respond to each notice fully. 3. Expeditious Removal

Mr. Morel has asserted that Corbis was not Mr. Morels authorized representative. (56.1 Stmt. 218). See Capitol Records, 821 F. Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q. at 1103 (notice merely stating all songs by particular artist, or some other vague descriptor is inadequate); Viacom, 718 F.Supp.2d at 528-29; UMG II, 665 F.Supp.2d at 1110. 10 See Capitol Records, 821 F. Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q. at 1104 (EMI had to provide sufficient information namely additional web addresses for MP3tunes to locate other infringing material); Viacom, 718 F.Supp.2d at 529 (URL or other information sufficient to permit service provider to locate the material on its own site is required); UMG II, 665 F.Supp.2d at 1110. 11 Such statements are necessary given the drastic consequences of allegations of infringement. If the content infringes, justice has been done. But if it does not, speech protected under the First Amendment could be removed. We therefore do not require a service provider to start potentially invasive proceedings if the complainant is unwilling to state under penalty of perjury that he is an authorized representative of the copyright owner, and that he has a good-faith belief that the material is unlicensed. Perfect 10, 488 F.3d at 1112.

9

21

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 29 of 58

Even if Corbis emails had put Getty Images on constructive notice, Getty Images satisfied its obligations by removing the images expeditiously indeed immediately when it received notice of their existence on its website. Where a copyright owner gives multiple notices identifying different alleged instances or categories of infringement, each successive notice may require the expeditious removal of additional works. UMG II, 665 F.Supp.2d at 1104, 1107 (Veoh has shown that when it did acquire knowledge of allegedly infringing material whether from DMCA notices, informal notices, or other means it expeditiously removed such material, satisfying its burden of expeditious removal). When Corbis emailed Getty Images on January 13 about the Photos at Issue, Getty Images searched its system and removed all images attributed to Morel within 37 minutes. (56.1 Stmt. 190, Cameron Decl. 15). When Corbis emailed on February 2 that additional copies of the images, attributed to Lisandro Suero, existed on Getty Images site, it removed those additional images within that same night. (56.1 Stmt. 216). This quick response surely qualifies as expeditious. E. Getty Images Did Not Receive a Financial Benefit Directly Attributable to the Infringing Activity or Have the Right and Ability to Control Such Activity. A service provider loses the benefit of the 512(c) safe harbor if it receives a financial benefit directly attributable to infringing activity and has the right and ability to control such activity. 512(c)(1)(B). Both elements must be met for the safe harbor to be denied on this basis. Io Group, 586 F.Supp.2d at 1150 (citation omitted). Neither was met here. 1. Direct Financial Benefit Getty Images did not receive a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity for purposes of 512(c)(1)(C). In setting this requirement, Congress distinguished between service providers engaged in legitimate business which charge the same for infringing

22

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 30 of 58

and non-infringing material, and those where the value of the service lies in providing access to infringing material. Viacom, 718 F.Supp.2d at 521 (citation omitted). A provider receives direct financial benefit only if it promotes infringing activity to enhance business, or charges more for infringing material than for non-infringing material, id.; Capitol Records, 821 F. Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q. at 1093; Wolk, 2011 WL 940056, at *7. Getty Images is engaged in a legitimate business that does not promote the availability of infringing content, attract customers based on such content or charge more for infringing content. 12 (56.1 Stmt. 35, 3839) 2. Right and Ability to Control Infringing Activity Nor did Getty Images have the right and ability to control infringing activity on its website. It was able to remove (and, when notified, it did remove) the Photos at Issue, but control of infringing activity in this context requires something more than the ability to remove or block access to materials posted on a service providers website. Capitol Records, 821 F. Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q. at 1105; Viacom, 2012 WL 1130851, at *12-13 (interpreting right and ability to control as the ability to block access would render the statute inconsistent because the statute presumes such access). Rather, it requires something more, id. at *13, such as prescreening content, providing extensive advice to users regarding content and editing user content. Wolk, 2011 WL 940056, at *6. Getty Images did not perform these functions with respect to the Morel Images. (56.1 Stmt. 49-50). Indeed, Getty Images could not have undertaken any such role, given the thousands of images AFP transmits every week. (56.1 Stmt. 48). Where a sites size and volume of user

12

Indeed, Getty Images strongly discourages infringing activity, through its website and its participation in industry organizations that promote copyright compliance. (56.1 Stmt. 35-40). Its clear copyright compliance policy requires all users to respect the rights of third parties. In short, Getty Images neither promoted nor financially benefitted from copyright infringement then or ever.

23

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 31 of 58

content preclude the service provider from controlling infringing activities, it is not deemed to have the right and ability to control such activity. (Photobucket does not engage in such activities, and the size of its website curtails its ability to do so.) Wolk, 2011 WL 940056 at *6; Io, 586 F.Supp.2d at 1153 (Veoh has submitted evidence indicating that it has received hundreds of thousands of video files from usersno reasonable juror could conclude that a comprehensive review of every file would be feasible.). 13 Here, AFP alone chose and transmitted photographs to the Getty Images database, without Getty Images participation. (56.1 Stmt. 49). Getty Images does not prescreen the content, advise what to transmit, edit the content or otherwise involve itself in any active manner. (56.1 Stmt. 50). It has never encouraged infringement or failed to police its own system; rather it requires its content providers to secure the necessary rights, and holds its customers to license restrictions regarding the use of content. (56.1 Stmt. 19, 32, 36-7). Like Veoh in the Io case, the record shows that Getty Images has taken down blatantly infringing content, promptly responds to infringement notices and terminates repeat offenders. Io Group, 586 F.Supp.2d at 1153-54. F. Getty Images Satisfied All of the Technical Requirements of the Statute Getty Images met the technical requirements of the statute. First, it has designated an agent to receive notices of infringement in keeping with 512(c)(2). (56.1 Stmt. 42). Second, it has adopted and reasonably implementeda policy that provides for the termination in

13

In Capitol Records, for example, plaintiff EMI contended that defendant MP3tunes, which had physical possession of its systems and servers and could monitor a users downloads and remove infringing content, had the right and ability to control infringing activity on its music-sharing site. This Court disagreed: MP3tunes users alone choose the websites they link to Sideload.com and the songs they sideload and store in their lockers. MP3tunes does not participate in those decisions. At worst, MP3tunes set up a fully automated system where users can choose to download infringing content. 821 F.Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q. at 1105 (citations omitted). See also Corbis, 351 F.Supp.2d at 1109-10 (where Amazon provided platform for third parties to list and sell merchandise, generated automatic email responses, provided transaction processing services and had the ability to identify and terminate vendors, but did not preview the products, edit the product descriptions, set prices or otherwise involve itself in the sale, it did not have right and ability to control infringing activity on platform).

24

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 32 of 58

appropriate circumstances of subscribers and account holders of the service providers system or network who are repeat infringers. 512(i). 14 (56.1 Stmt. 41). Third, Getty Images accommodates and does not interfere with standard technical measures taken by copyright owners to protect their intellectual property (56.1 Stmt. 45). 15 G. Mr. Morel Is Not Entitled to Any Relief on His Copyright Claims When a service provider qualifies for protection under 512(c), it is shielded from liability for all monetary relief for direct, vicarious and contributory infringement. Viacom, 718 F.Supp.2d at 526 (internal quotations omitted), affd in relevant part, Viacom, 2012 WL 1130851, at *16. In addition, because the safe harbor limits the available relief on any of Morels copyright counterclaims against Getty Images to certain narrow forms of injunctive relief, and because there is no basis for these available forms of injunctive relief, the claims should be dismissed in their entirety. Io Group, 586 F.Supp.2d at 1154-55 (Because the court finds thatVeoh qualifies for safe harbor under Section 512(c), the only relief available to plaintiff is the limited injunctive relief under Section 512(j). In this case, before it ever received notice of any claimed infringement, Veoh independently removed all adult content, including video files of plaintiffs

Implementation has been held reasonable if: the service provider (1) has a system for dealing with takedown notices, (2) does not interfere with the copyright owners ability to issue notices, and (3) under appropriate circumstances terminates users who repeatedly or blatantly infringe copyrights. Capitol Records, 821 F. Supp.2d 627, 101 U.S.P.Q. at 1099. On the other hand, service providers have no affirmative duty to police their users. Id. Getty Images had a system for dealing with takedown notices, did not interfere with copyright owners ability to issue such notices and had a policy of terminating, in appropriate circumstances and at Getty Images sole discretion, account holders who infringe the intellectual property rights of Getty Images or any third party in its terms of service. (56.1 Stmt. 41, 43-45, Cameron Decl. 4, Ex. A). 15 The term standard technical measures is defined as technical measures that are used by copyright owners to identify or protect copyrighted works which (a) have been developed pursuant to a broad consensus of copyright owners and service providers in an open, fair, voluntary, multi-industry standards process; (b) are available to any person on reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms and (c) do not impose substantial costs on service providers or substantial burdens on their systems or networks. 512(i)(2).

14

25

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 33 of 58

works, and it no long allows such material on veoh.com. Thus any injunctive relief to which Io would be entitled is moot.) 16 3. Getty Images Cannot Be Held Directly Liable For Copyright Infringement Because It Did Not Engage In Any Volitional Conduct Morels direct copyright claim against Getty Images also fails for the simple reason that Getty Images did not engage in sufficient volitional conduct in creating a copy of the infringing works, which is an important element of direct liability. Cartoon Network LP, LLLP v. CSC Holdings, Inc., 536 F.3d 121, 131 (2nd Cir. 2008); see also CoStar Group, Inc. v. LoopNet, Inc., 373 F.3d 544, 555 (4th Cir. 2004) ([W]e hold that [internet service providers], when passively storing material at the direction of users in order to make that material available to other users upon their request, do not copy the material in direct violation of 106 of the Copyright Act.); Flava Works, Inc. v. Gunter, No. 10 C 6517, 2011 WL 1791557 at *2 (N.D. Ill., May 10, 2011) (to establish liability for direct copyright infringement, a plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant engaged in volitional conduct that causes a copy to be made.). In Cartoon Network, the Second Circuit examined Cablevisions Remote Storage Digital Video Recorder (RS-DVR) system, which allowed its customers, cable television subscribers, to select programs to be reproduced onto Cablevisions hard drives and watched later. See Cartoon

Where, as here, a service provider qualifies for the 512(c) safe harbor, 512(c) limits the available injunctive relief to an order restraining the service provider from providing access to infringing material or activity on its website, 512(j)(1)(A)(i), or requiring it to terminate a subscriber or account holders account, 512(j)(1)(A)(ii) or [s]uch other injunctive relief as the court may consider necessary to prevent or restrain infringement at a particular site if such relief is the least burdensome to the service provider among the forms of relief comparably effective for that purpose, 512(j)(1)(A)(iii). To the extent Mr. Morel seeks injunctive relief blocking access to infringing material, it is unnecessary; when a service provider has already taken down the infringing content, the Court need not enjoin it to do so under 512(j)(1)(A)(i). Wolk, 2011 WL 940056, at *7 (It is undisputed Photobucket is already removing allegedly infringing works when given DMCA-compliant notice so that there is no need for an injunction requiring it to do the same.). To the extent Mr. Morel seeks other injunctive relief, it is either improper because the sought injunction extends to clients, subscribers, licensees and customers rather than the parties or those in active concert or participation with them, Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d)(2); GMA Accessories, Inc. v. Eminent, Inc., No. 07 Civ. 3219, 2008 WL 2355826, at *12-13 (S.D.N.Y May 29, 2008) (active concert or participation requires the non-party to be either legally identified with the party or intertwined in a manner that goes beyond arms length business transactions), or because it seeks injunctive relief outside of the scope of 512(j).

16

26

DWT 19404085v4 0053349-000076

Case 1:10-cv-02730-AJN-MHD Document 130

Filed 04/27/12 Page 34 of 58