Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The ABCs of CPR

Uploaded by

dbryant0101Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The ABCs of CPR

Uploaded by

dbryant0101Copyright:

Available Formats

3 HOURS

Continuing Education

Overview: Survival rates for cardiac arrests

A review of the latest changes to the

that occur in hospitals and outside them con- American Heart Association’s cardio-

tinue to be low (17% and 6%, respectively), pulmonary resuscitation and emergency

and fewer than one-third of patients who cardiovascular care guidelines.

have an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest receive

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Consequently, a number of changes were

“

W

hy do they keep updating these guidelines? Didn’t they make

made to the 2005 American Heart changes just last year?” It does seem so. In 2005 the

American Heart Association (AHA) published another ver-

Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary sion of its Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular and Emergency Cardiovascular Care,1 but it had been five

years since the last published revisions. The AHA first established guide-

Care. The changes were intended to simplify lines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in 1974 and has revised

them five times since, in 1980, 1986, 1992, 2000, and 2005. The 2005

CPR in order to increase its use and effective-

guidelines cover all aspects of emergency cardiac care; at the same time,

ness by both clinicians and nonprofessionals. they represent an attempt to simplify CPR procedures so that more

health care professionals and lay rescuers might learn them and perform

This article summarizes the primary changes them correctly. (The complete guidelines are available online at

to the recommendations, including a univer- http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/vol112/24_suppl.)

Much is at stake. Despite decades of efforts to promote CPR, the sur-

sal 30-to-2 compression-to-ventilation ratio for vival rate for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest remains low worldwide,

all lone rescuers, the need for compressions averaging 6% or less.2, 3 In the United States, sudden cardiac arrest is a

leading cause of death,4-6 resulting in an estimated 330,000 out-of-hospital

of sufficient depth and number, and the

replacement of the three-shock model of ini- Linda Mutchner is an infusion nurse at Frederick Memorial Hospital in Frederick, MD.

She also is a coowner of Core Training Consultants, Taneytown, MD, which offers

tial defibrillation with one that recommends a courses in cardiopulmonary resuscitation, first aid, infusion, and chemotherapy. Contact

author: lmutchner@msn.com. The author of this article has no significant ties, financial

single shock, now seen as an adequate pre- or otherwise, to any company that might have an interest in the publication of this edu-

cational activity.

cursor to CPR.

Much of this article is adapted from the 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines

for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, published in

the December 13, 2005, Circulation supplement: Circulation 2005 Dec 13;112(24

Suppl):IV1-203.

60 AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 http://www.nursingcenter.com

By Linda Mutchner, BSN, RN, CRNI, OCN

deaths annually.7 Ventricular fibrillation plays a role Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) was formed to

in most cases of sudden cardiac arrest,3, 5, 8 and defib- identify, review, and reconcile international research

rillation in the first five minutes after collapse and practice related to CPR and emergency cardio-

greatly increases the chances of survival.9 Too often, vascular care. ILCOR’s founding member organiza-

however, the time to defibrillation exceeds five min- tions were the AHA, the European Resuscitation

utes.2 Casinos, airlines, airports, and police forces Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada,

that have “first-responder programs” involving the the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa, and the

use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) Australian Resuscitation Council, later joined by

show survival rates to hospital discharge of 49% to the Consejo Latino-Americano de Resuscitación

80%,10-13 but survival rates decrease 7% to 10% for and the New Zealand Resuscitation Council.

each minute between collapse and defibrillation Since 1993 representatives from the ILCOR

when CPR is not provided.14 When initiated as soon member councils have been evaluating research find-

as possible after a patient’s collapse, CPR performed ings and working toward developing resuscitation

correctly and followed by defibrillation is a central guidelines, meeting 22 times. The AHA hosted the

aspect of the “chain of survival” for those who have first ILCOR conference in 1999, recommendations

a sudden cardiac arrest.15 Fewer than one-third of from which were published in 2000.20 Researchers

patients who have an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest from the ILCOR member councils continued to eval-

receive CPR,15, 16 suggesting a need for better and uate research findings, in a process that culminated

more widespread training of nonprofessionals. in the 2005 International Consensus Conference

And hospital nurses and physicians do not on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency

always perform CPR effectively.17, 18 The new AHA Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recom-

guidelines warn clinicians against hyperventilating mendations (hereafter referred to as the 2005 con-

patients (providing too many breaths at too great a sensus conference). The conferees undertook the

tidal volume), interrupting compressions too often most extensive review to date of international scien-

or for too long, and compressing the chest too tific evidence on CPR, using a carefully structured

slowly and too shallowly, with a resulting drop in process of ongoing disclosure and management of

coronary perfusion. At the same time, advanced potential conflicts of interest. They paid particular

interventions such as endotracheal intubation don’t attention to streamlining the guidelines in order to

make a significant difference in survival rates; reduce the amount of information that rescuers need

according to one multisite, observational study, only to remember and to clarifying the fundamental tasks

17% of patients who experience in-hospital cardiac that rescuers should perform.

arrest survive to discharge.19 More than 280 international experts were

divided into six task forces, on basic life support,

INTERNATIONAL CONSENSUS advanced life support, acute coronary syndromes,

The 2000 AHA guidelines resulted from a process pediatric life support, neonatal life support, and

begun in 1993, when the International Liaison overlapping topics such as education. (Additional

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 61

task forces—separate from the ILCOR process, Recognition and “activation”: avoid delays.

although findings are summarized in the guide- Early recognition of sudden cardiac arrest is the key

lines—were created to consider stroke and first-aid.) to increasing the chances of survival. For lay rescuers,

The task forces proposed hypotheses; one or two checking the carotid pulse is an inaccurate method of

international experts were appointed to review confirming the presence or absence of circulation;

research on each topic, determine levels of evidence, according to research, they fail to recognize the

and develop a draft of recommendations for treat- absence of a pulse in 10% of pulseless victims (poor

ment. At the 2005 consensus conference such a sensitivity) and fail to detect a pulse in 40% of victims

draft was discussed, with a special focus on the with a pulse (poor specificity).20 Health care providers

quality of evidence and issues of financial disclosure also often take too long in checking for a pulse and

and conflict of interest. The wording was refined, and inaccurately assess its presence or absence.21, 22 There

prior to publication, the final document was approved is no evidence that checking for movement, breath-

by all ILCOR members and by an international edi- ing, or coughing is any more reliable than checking

torial board. for a pulse as a method of recognizing the signs of cir-

While universally applicable international guide- culation. Taking too much time to check for a pulse

lines may not be an achievable short-term goal— delays the rescuer’s initiation of chest compressions

because of regional differences in health care and (class IIb). Agonal respiration is common in the early

contradictory or weak evidence available on some stages of cardiac arrest and can mislead a rescuer into

topics—many treatment recommendations have been thinking that CPR isn’t required.

agreed upon and simplified in ways that should make Recommendations

the training of professionals and nonprofessionals • If the person is unconscious (unresponsive), not

more efficient and the delivery of CPR more effective. moving, and not breathing (or has agonal breath-

What follows is a look at changes in the guidelines as ing), lay rescuers shouldn’t check for pulse; they

well as the scientific reasoning behind them. should dial 911, obtain an AED if one is avail-

able, perform CPR for two minutes (or approxi-

ADULT BASIC LIFE SUPPORT mately five cycles, with one cycle defined as 30

Major recommendations in the 2005 AHA guide- compressions and two ventilations), and then use

lines were assigned to “classes” meant to reflect the an AED if they are trained to use one. (There are

level of current evidence found to support them and two types of AEDs—those sold before 2003 tend

the weight they should be given in practice, with the to be monophasic, delivering just one shock at a

caveat that much of the evidence we have currently time, while the newer biphasic models deliver a

is derived not from clinical trials but from non- dual shock of lower energy.) If an AED is not

randomized or retrospective trials or from animal available, lay rescuers should continue CPR with-

models. These are as follows (and appear through- out interruption until emergency help arrives.

out the text to indicate the strength of particular • Clinicians should check for the absence of nor-

recommendations): mal, adequate breathing and pulse (taking no

• Class I: the benefit clearly outweighs the risk; the more than 10 seconds to do so) before beginning

procedure, treatment, or assessment should be CPR (class IIa).

performed. • Clinicians should adapt the sequence of rescue

• Class IIa: the benefit is likely to outweigh the risk. actions to the probable cause of arrest. If a lone

It’s reasonable to follow the recommendation. health care provider sees someone collapse sud-

• Class IIb: the benefit is greater than or equal to denly, the arrest is likely to be cardiac in origin and

the risk. Following the recommendation may be the provider should dial 911, obtain and use an

considered. AED (class I), and then provide CPR for two min-

• Class III: the risk is greater than or equal to the utes (five cycles) before rechecking the rhythm. If

benefit. The procedure, treatment, or assessment an AED is not available, she or he should continue

is not helpful, may be harmful, and should not be CPR until emergency medical services arrive.

performed. • If the lone health care provider did not witness

• Class indeterminate: research has not begun or is the person’s collapse, she or he should perform

ongoing. No recommendations can be made at CPR for two minutes and then use an AED, if

this time. available (class IIb). If the provider aids a victim

Recommendations were also distinguished accord- of likely asphyxial (usually respiratory) arrest of

ing to whether they were meant for health care any age, she or he should give five cycles of CPR

providers, for lay rescuers, or for both. The follow- before leaving the victim to dial 911 (class IIa).

ing is a summary of changes in the guidelines for Airway: keep it simple. Maintaining the airway

adult basic life support. and providing adequate ventilation are crucial dur-

62 AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 http://www.nursingcenter.com

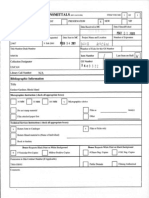

Table 1. Summary of Basic Life Support ABCD Maneuvers for Infants, Children, and Adults

MANEUVER ADULT CHILD INFANT

(Maneuvers performed only by health (For lay rescuers, adults are defined as those 8 years (For lay rescuers, children are those 1–8 (For all rescuers, infants are defined

care providers are indicated by “HCP”) of age or older; for HCPs, adolescent or older) years of age; for HCPs, 1 year to adolescent) as those under 1 year of age)

Activate (Call) Call when victim is found un- Call after performing 5 cycles of CPR

emergency response num- responsive

ber (lone rescuer) HCP: if asphyxial arrest is likely, call For sudden, witnessed collapse, call after verifying

after 5 cycles (2 minutes) of CPR that victim is unresponsive

AIRWAY Head tilt–chin lift (HCP: if trauma suspected, use jaw thrust)

BREATHS 2 effective breaths at 1 second 2 effective breaths at 1 second per breath

per breath

HCP: rescue breathing 10 to 12 breaths per minute 12 to 20 breaths per minute (1 breath every 3 to 5

without chest compressions (1 breath every 5 to 6 seconds) seconds)

HCP: rescue breathing for 8 to 10 breaths per minute (1 breath every 6 to 8 seconds)

CPR with advanced airway

Foreign-body airway Abdominal thrusts Back slaps and chest thrusts

obstruction

CIRCULATION

HCP: pulse check Carotid artery Brachial or femoral

(10 seconds or less) (HCP can use femoral artery in child) artery

Compression landmarks Center of chest, between nipples Just below nipple line

Compression method: 2 hands: heel of 1 hand, other 2 hands: heel of 1 hand 1 rescuer: 2 fingers

• push hard and fast hand on top with second on top or HCP, 2 rescuers: 2-

• allow complete recoil 1 hand: heel of 1 hand thumb–encircling-hands

only technique

Compression depth 11/2 to 2 inches Approximately 1/3 to 1/2 the depth of the chest

Compression rate Approximately 100 per minute

Compression-to-ventilation 30 to 2 (1 or 2 rescuers) 30 to 2 (single rescuer)

ratio HCP: 15 to 2 (2 rescuers)

DEFIBRILLATION

Automatic external defibril- Use adult pads. Do not use child HCP: use AED as soon as No recommendation for

lator (AED) pads or a child system. possible for sudden and in- infants less than 1 year

HCP: for out-of-hospital response, hospital collapse.

you may provide 5 cycles (2 min- All: after 5 cycles of CPR (out

utes) of CPR before shock if of hospital). Use child pads

response time is longer than 4 to and system for child 1 to 8

5 minutes and arrest was not wit- years old if available. If child

nessed. pads and system are not

available, use adult AED

and pads.

Note: information appropriate for use in newborns is not included.

Used with permission from American Heart Association. Currents in Emergency Cardiovascular Care 2005–2006;16(4)15.

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 63

ing CPR (class I). The best method of opening an Chest compressions: “push hard, push fast.”

airway is the head tilt–chin lift maneuver (class IIa). Effective chest compressions are essential (class I).

The rescuer should reposition the head if the first The new guidelines strongly emphasize that com-

ventilation does not cause the chest to rise. All such pressions should be given at a rate of about 100 per

repositionings cause spinal movement, and studies minute, with a depth of 1.5 to 2 in., over the lower

in cadavers have shown that chin lifts (with or with- half of the sternum, allowing the chest to completely

out head tilts) and jaw thrusts cause substantial recoil (equal compression and relaxation time). (The

movement of the cervical vertebrae,23 but no studies guidelines state that the “compression rate refers to

have evaluated the effects of these movements on the speed of compressions, not the actual number of

people with suspected spinal injuries. When spinal compressions.”) Studies have suggested that in

injury is suspected, manual spinal motion restriction almost 40% of cases, in-hospital chest compressions

should be employed while the jaw thrust maneuver may be too shallow.17 Incomplete recoil of the chest

is used to open the airway. This is safer than using and inadequate depth and rate of compressions may

immobilization devices, which may interfere with result from rescuer fatigue.25 Incomplete recoil is also

the airway during CPR (class IIb). associated with higher intrathoracic pressure,

Recommendations decreased coronary perfusion, and decreased cere-

• Lay rescuers should be taught only the head bral perfusion.26 When chest compression is 20% to

tilt–chin lift technique for both injured and unin- 50% of the total combined chest compression and

jured people (class IIa). (The jaw thrust maneuver relaxation time, coronary and cerebral perfusion

is considered too difficult for nonprofessionals to increases, as shown in animal studies.27, 28

learn and perform.) Studies involving clinicians performing CPR show

• Clinicians should use the jaw thrust maneuver if that chest compressions may not be provided for as

injury to the cervical spine is suspected (class IIb); much as half of the total arrest time.17, 18, 29 In animal

if that does not open the airway, the head studies, interrupted chest compressions were associ-

tilt–chin lift technique should be used. If two ated with reduced coronary artery perfusion pressure,

health care professionals are present, one can reduced return of spontaneous circulation, reduced

manually stabilize the head and neck while the survival rates, and reduced postresuscitation myocar-

other performs CPR. dial function.30-32

Ventilation: practice moderation. After cardiac Recommendations

arrest with ventricular fibrillation, diminished car- • Chest compressions should be performed at a

diac output causes myocardial and cerebral ischemia, rate of 100 per minute, over the lower half of the

but the blood oxygen level remains high for the first sternum, at a depth of 1.5 to 2 in. (class IIa).

several minutes. Therefore, administering breaths is • Complete recoil of the chest should be allowed

not at first as important as administering chest com- between compressions; a duty cycle of 50% (that

pressions. During CPR, blood flow to the lungs is is, equal time given to chest compression and

reduced to 25% to 35%, and achieving adequate relaxation) is recommended because it is easy to

oxygenation requires a lower tidal volume and achieve with practice.33

fewer ventilations.24 Hyperventilation is unneces- • CPR should be interrupted as infrequently as

sary and even harmful; it increases intrathoracic possible; interruptions should last no longer than

pressure, decreases venous return to the heart, and 10 seconds, except for the performance of inter-

diminishes cardiac output. Hyperventilation can ventions such as defibrillation (class IIa).

also cause gastric distention leading to regurgitation • Lay rescuers should be instructed not to stop

and aspiration and can elevate the diaphragm, CPR to check for signs of circulation.

restricting lung movement and elasticity. It may, Compression and ventilation: a new ratio.

however, be necessary to provide high pressures to Animal studies and theoretical calculations have been

ventilate patients with an obstructed airway or poor used to determine the compression-to-ventilation ratio

lung compliance. most likely to increase the number of compressions

Recommendations given, reduce the likelihood of hyperventilation, mini-

• Two rescue breaths, one second each (class IIa), mize interruptions, and simplify instruction.34, 35 While

should be given with enough volume to see the more study is needed, a consensus has been reached

chest rise (class IIa). in the current guidelines that a 30-to-2 ratio best

• Rapid or forceful breaths should be avoided. meets these criteria. This ratio is, however, demand-

• For a victim with a pulse, 10 to 12 breaths per ing to maintain; although rescuers may deny fatigue

minute (one breath every five to six seconds) for up to five minutes of performing CPR, after one

should be given; more can be dangerous (class minute they often give compressions that are too

IIa). shallow.25

64 AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 http://www.nursingcenter.com

Recommendations tion will convert.31, 40 Analysis of AED data shows

• All rescuers should use acompression-to-ventilation that a three-shock sequence delays delivery of chest

ratio of 30 to 2—that is, giving 30 compressions compressions by up to 37 seconds (from delivery of

for every two ventilations (class IIa). the first shock to administration of the first post-

• During two-person CPR, compressions should shock compression).32 This delay was found difficult

be paused briefly to provide ventilations; in to justify in light of the fact that the first shock using

mechanically ventilated patients, eight to 10 ven- either biphasic or monophasic defibrillators has been

tilations per minute (one every six to eight sec- found to convert ventricular fibrillation more than

onds) should be given without a pause in 90% of the time.41, 42 If one shock fails to eliminate

compressions (class IIa). ventricular fibrillation, the incremental benefits of

• When two rescuers are present, compressors another shock are low and resuming CPR is likely to

should change every two minutes, switching in lead to greater efficacy from subsequent shocks

less than five seconds, if possible (class IIb). because it will provide needed oxygen to the heart.

• Lay rescuers should be instructed to use only Recommendations

compressions if they are not willing or able to • Clinicians should ensure an efficient coordina-

deliver rescue breaths (class IIa). tion between CPR and defibrillation (class IIa).

• For witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the

DEFIBRILLATION: ADULTS clinician and trained rescuer should use the AED

Immediate defibrillation is the first and best response as soon as it is available, giving just one shock

to witnessed cardiac arrest with a short time to inter- followed by five cycles of CPR (class IIb).

vention (class I). In cases of sudden cardiac arrest with • When ventricular fibrillation is present and the

prolonged ventricular fibrillation, survival rates are arrest is unwitnessed, the lone rescuer should

highest when CPR is provided immediately and defib- give five cycles of CPR, deliver just one shock,

rillation begins within three to five minutes.10, 14, 15, 36 and then immediately resume CPR, beginning

Chest compressions generate a small but critical with chest compressions (class IIa). There should

amount of blood flow and consequently oxygen to be no delays or interruptions to check for pulse

the brain and myocardium. Two studies found that or rhythm.

when emergency providers’ time to arrival was four • When two rescuers are on hand, the rescuer

or five minutes or longer, victims who received one operating the AED should be prepared to deliver

and a half to three minutes of CPR before defibrilla- a first shock as soon as the compressor removes

tion had increased rates of initial resuscitation, sur- her or his hands and the “all clear” is given.

vival to hospital discharge, and one-year survival When possible, the compressor should continue

than did those who received immediate defibrilla- with chest compressions while the other rescuer

tion.37, 38 But one randomized trial found no improve- is attaching the AED. After five cycles of CPR,

ment in outcomes when 90 seconds of CPR was the AED should be used to analyze the rhythm

performed before defibrillation in patients with ven- and deliver another shock, if indicated (class IIb).

tricular fibrillation or tachycardia.39 • If the AED detects a rhythm other than ventricu-

When ventricular fibrillation is present for sev- lar fibrillation, it may instruct the rescuer to

eral minutes, the heart consumes most of the oxy- resume CPR immediately, beginning with chest

gen and electrolytes it needs to contract effectively. compressions (class IIb), although some AEDs

Even if a shock does terminate ventricular fibrilla- may only instruct the rescuer to reassess the vic-

tion, the heart probably won’t pump effectively for tim and determine whether CPR is needed.

several minutes because of the inadequate oxygen Concerns that chest compressions might provoke

supply. Data obtained from a Seattle first-responder recurrent ventricular fibrillation in the presence

team equipped with AEDs showed survival rates of a postshock organized rhythm do not appear

actually decreased as a result of a focus on initiating to have a basis.43

defibrillation instead of CPR.37 A period of CPR

before shock delivery will provide some oxygen to FOREIGN-BODY AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION: ADULTS

cardiac muscle, thus making a shock more likely to Early recognition of foreign-body airway obstruc-

convert it to a normal rhythm. tion is crucial. Signs of severe airway obstruction,

At the time of the consensus conference there had such as difficulty breathing, silent cough, cyanosis,

been no studies comparing a one-shock protocol or the inability to speak, should prompt an immedi-

with a protocol of three stacked shocks. Animal ate response. The use of back slaps, abdominal

studies, however, strongly suggest that interruptions thrusts, and chest thrusts are all effective ways of

in the administration of compressions are associated relieving an obstruction, but about half of obstruc-

with a decreased probability that ventricular fibrilla- tions aren’t relieved by a single technique.44 A com-

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 65

bination of back slaps, abdominal thrusts, and chest way management (other than those made for

thrusts increases the chances of success.44 adults). Several points, however, were emphasized.

In cases of foreign-body airway obstruction, CPR Rescuers who have difficulty obtaining an adequate

should be performed when the person is uncon- seal over an infant’s mouth and nose should provide

scious. Studies of cadavers and anesthetized volun- mouth-to-mouth ventilations while pinching the

teers show that higher sustained airway pressures nose closed. Adequate ventilation remains the prior-

can be generated using chest thrusts instead of ity, even when spinal injury is suspected. The health

abdominal thrusts.45, 46 care provider should use the jaw thrust maneuver,

as with the adult victim, if adequate ventilations can

be achieved. If not, the head tilt–chin lift technique

Initiating cardiopulmonary resusci- should be used. Nonprofessionals should use the

head tilt–chin lift technique only.

tation before dialing 911 remains Ventilation. There are no recommended changes

to the 2000 guidelines concerning ventilation tech-

the best approach to responding to niques. The 2005 guidelines do note, however, that

when rescuers are using a mask system, they should

an unresponsive child. make sure the mask size is appropriate to the infant

or child; ensuring a tight seal can take time away

from CPR and requires training and periodic

Recommendations retraining. Hyperventilation should be avoided with

• For simplification of training, a rapid sequence of the infant and child as it is with the adult.

abdominal thrusts is advised for the conscious Recommendations

victim of foreign-body airway obstruction until • Two rescue breaths of one second each should be

the obstruction is relieved (except for infants given (class IIa), with enough volume to see the

under one year of age) (class IIb). chest rise (class IIa). Rapid or forceful breaths

• Chest thrusts should be used for obese victims or should be avoided.

those in the late stages of pregnancy (class IIb). • Rescuers should deliver 12 to 20 rescue breaths

• If the victim is unconscious, the rescuer should first per minute (one breath every three to five sec-

dial 911 and then begin CPR (using the 30-to-2 onds) when the victim has a pulse greater than or

compression-to-ventilation ratio), having looked equal to 60 beats per minute (only professionals

for and removed the object (only if it is clearly should attempt to palpate the pulse) and signs of

visible) before ventilation (class indeterminate). adequate perfusion, such as improved color or

CPR should not be interrupted to search the air- warmness to the touch (class IIa).

way for a foreign body. Chest compressions. Profound bradycardia

(heart rate lower than 60 beats per minute) in the

PEDIATRIC BASIC LIFE SUPPORT presence of poor perfusion (pallor or cyanosis) indi-

Recognition. Because hypoxia–ischemia resulting cates that cardiac arrest may soon follow; chest

from asphyxia is the most common cause of cardiac compressions should begin immediately. A heart

arrest in infants and children—and ventricular fibril- rate at which chest compressions should be initiated

lation is the cause in just 5% to 15% of pediatric in children hasn’t been identified; the guidelines rec-

cases47, 48—the rescuer’s actions should be determined ommend starting compressions at a rate of fewer

by the cause of the arrest, not the age of the victim. than 60 beats per minute with signs of poor perfu-

Initiating CPR before dialing 911 remains the best sion because it’s easy to teach and remember.

approach to responding to an unresponsive child. Infants. The two-thumb–encircling-hands tech-

Recommendations nique—performed by encircling the infant’s chest

• All rescuers should respond according to the cause with both hands, spreading the fingers around the

of the arrest. In children whose collapse is unwit- thorax, and placing the thumbs over the lower half

nessed or not sudden, CPR should be initiated of the sternum—is recommended for health care

immediately and performed for five cycles before providers when two rescuers are present. The

911 is dialed. In the case of a witnessed, sudden thumbs compress the sternum; the fingers provide

collapse—for example, during an athletic event— counterpressure on the infant’s back (class IIa).

the cause is likely to be ventricular fibrillation Studies using animals and mechanical models show

and the rescuer should phone for help, get and use that the two-thumb–encircling-hands technique

the AED (if trained to do so), and begin CPR. produces higher coronary perfusion pressures and

Airway. No new evidence was obtained to merit more consistently correct depth and force of com-

changes to the recommendation for pediatric air- pressions than the two-finger technique does.49-52 Lay

66 AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 http://www.nursingcenter.com

rescuers or a lone rescuer should use the two-finger allow for ventilations. For patients with an

technique, placing the fingers just below the inter- advanced airway such as an endotracheal tube,

mammary line (since it’s impossible to encircle the eight to 10 ventilations should be given per

infant’s chest, compress the chest with two fingers, minute, without attempting to synchronize with

and provide ventilations at the recommended rate). compressions.

Children. No new data show the superiority of the

one-hand over the two-hand compression technique DEFIBRILLATION: CHILDREN AND INFANTS

(class indeterminate). Most important are that the Children whose sudden collapse is witnessed (as can

depth of compressions be about one-third to one-half occur during an athletic event) are likely to have ven-

the depth of the chest and that there be complete tricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycar-

recoil and minimal interruptions, as with adults. dia and require immediate CPR and defibrillation.

Recommendations Institutions that care for children and have an AED

• The two-finger technique is considered best for program should have an AED capable of recognizing

the lone rescuer to decrease the time between shockable rhythms in children and a pediatric “dose-

compressions and ventilations and to minimize attenuating system”—a feature that automatically

interruptions in compressions. The two-thumb– adjusts the dose the device delivers. Data show that

encircling-hands technique should be used when AEDs can be used safely and effectively in children

there are two rescuers. one to eight years of age.55-57 If an AED with a pedi-

• Both the one-hand and two-hand techniques for atric dose-attenuating system is not available in an

chest compressions in children are acceptable; emergency, a standard AED should be used.

rescuers can be taught the same technique (two- A standard adult AED should be used for chil-

hand) for both the adult and child victims. dren older than age eight and for those weighing

• As with the adult, compressions should be per- more than 25 kg (55 lbs.). Standard AEDs may also

formed at a rate of 100 per minute for both the come equipped with adult and pediatric pads and

infant and the child, to a depth of one-third to cables or contain a key or switch system for select-

one-half of the chest. Complete chest recoil ing a lower dose.

should be allowed, with equal time for compres- As with adults, there’s insufficient evidence to

sion and release. support a one-shock protocol over a three-stacked-

Compression-to-ventilation ratio. In a study using shocks protocol for children; however, one shock is

pediatric manikins, “rescuers” were told to adhere recommended.

to a compression-to-ventilation ratio of 5 to 1 and Recommendations

a compression rate of 100 per minute; however • When rescuers witness the sudden collapse of a

fewer than 60 compressions per minute were per- child, they should dial 911, get and use an AED

formed, although these were ideal circumstances.53 if trained to do so, and then perform CPR if

Interruptions in compressions for ventilation and needed.

attachment of the AED can result in a significant • For the unwitnessed collapse of a child, the res-

decrease in cardiac-perfusion pressure.40 Animal stud- cuer should perform five cycles of CPR, then dial

ies, manikin studies, and mathematical models have 911 and obtain an AED, if available.

examined various ratios (15 to 2, 5 to 1, and others) • There is insufficient evidence to make a recom-

and failed to provide adequate data to identify an mendation for or against using any AED in infants

optimal compression-to-ventilation ratio for infants less than one year of age (class indeterminate).55, 56

and children.34, 40, 54 • Coordination between CPR and defibrillation is

Recommendations important to reduce interruptions, and CPR

• Lone rescuers should use a compression-to- should be resumed immediately after defibrilla-

ventilation ratio of 30 to 2 for all age groups. tion without checking for pulse.

• When health care providers are rescuing, they

should use a compression-to-ventilation ratio of FOREIGN-BODY AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION: CHILDREN AND

15 to 2. INFANTS

• Interruptions in CPR should be as infrequent as No new recommendations have been made for the

possible and limited to no longer than 10 sec- management of foreign-body airway obstruction in

onds, except for specific interventions such as the child and infant. For the child, abdominal

intubation. thrusts should be performed until the object is

• When two rescuers are present, compressors removed or the victim becomes unconscious. For

should switch every two minutes, doing so in less the infant, administer five back slaps and five chest

than five seconds, if possible. When there is no thrusts until the object is removed or the victim

advanced airway, a short pause must be taken to becomes unconscious. When the infant becomes

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 67

unconscious, initiate CPR at a ratio of 30 to 2 when 15. Valenzuela TD, et al. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac

the rescuer is alone and 15 to 2 if two health care arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model.

Circulation 1997;96(10):3308-13.

professionals are present; look for the object and

16. Gallagher EJ, et al. Effectiveness of bystander cardiopul-

remove it if it can be seen prior to ventilation. Do monary resuscitation and survival following out-of-hospital

not interrupt CPR to check for the object. cardiac arrest. JAMA 1995;274(24):1922-5.

17. Abella BS, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation

during in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2005;293(3):305-

FUTURE DIRECTIONS 10.

Continuous quality improvement is one way of 18. Abella BS, et al. Chest compression rates during cardiopul-

monitoring the quality of CPR delivered and of monary resuscitation are suboptimal: a prospective study

during in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2005;111(4):

tracking outcomes up to hospital discharge. In an 428-34.

effort to compile more accurate statistics on out- 19. Peberdy MA, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults

comes, the Centers for Disease Control and in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the

Prevention has begun collecting data that include National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

Resuscitation 2003;58(3):297-308.

survival to hospital discharge and whether or not 20. American Heart Association, International Liaison Committee

the patient is mentally intact. Defibrillators on Resuscitation. Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary

equipped to collect data on compression rate, depth Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 3:

adult basic life support. Circulation 2000;102(8 Suppl):

of compression, and ventilation rate will help to I22-59.

improve outcomes of cardiac arrest. 21. Eberle B, et al. Checking the carotid pulse check: diagnostic

The science of resuscitation is evolving rapidly accuracy of first responders in patients with and without a

and it would not be in patients’ best interest for pulse. Resuscitation 1996;33(2):107-16.

22. Moule P. Checking the carotid pulse: diagnostic accuracy in

providers to wait another five years to make students of the healthcare professions. Resuscitation 2000;

changes to their practice. ILCOR members will con- 44(3):195-201.

tinue to review new research and, when necessary, 23. Hauswald M, et al. Cervical spine movement during airway

publish interim advisory statements to update the management: cinefluoroscopic appraisal in human cadavers.

Am J Emerg Med 1991;9(6):535-8.

guidelines. ▼ 24. Baskett P, et al. Tidal volumes which are perceived to be

adequate for resuscitation. Resuscitation 1996;31(3):231-4.

REFERENCES 25. Greingor JL. Quality of cardiac massage with ratio

1. 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardio- compression-ventilation 5/1 and 15/2. Resuscitation 2002;

pulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular 55(3):263-7.

Care. Circulation 2005;112(24 Suppl):IV1-203. 26. Yannopoulos D, et al. Effects of incomplete chest wall

2. Nichol G, et al. A cumulative meta-analysis of the effective- decompression during cardiopulmonary resuscitation on

ness of defibrillator-capable emergency medical services for coronary and cerebral perfusion pressures in a porcine

victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med model of cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2005;64(3):363-72.

1999;34(4 Pt 1):517-25. 27. Halperin HR, et al. Determinants of blood flow to vital

3. Rea TD, et al. Incidence of EMS-treated out-of-hospital cardiac organs during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in dogs.

arrest in the United States. Resuscitation 2004;63(1):17-24. Circulation 1986;73(3):539-50.

4. Chugh SS, et al. Current burden of sudden cardiac death: 28. Feneley MP, et al. Influence of compression rate on initial

multiple source surveillance versus retrospective death success of resuscitation and 24 hour survival after pro-

certificate-based review in a large U.S. community. J Am longed manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation in dogs.

Coll Cardiol 2004;44(6):1268-75. Circulation 1988;77(1):240-50.

5. Vaillancourt C, Stiell IG. Cardiac arrest care and emergency 29. Wik L, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation dur-

medical services in Canada. Can J Cardiol 2004;20(11):1081-90. ing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2005;293(3):299-

6. Zheng ZJ, et al. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 304.

1989 to 1998. Circulation 2001;104(18):2158-63. 30. Berg RA, et al. Chest compressions and basic life support-

7. American Heart Association. Sudden cardiac death. 2006. defibrillation. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37(4 Suppl):S26-35.

http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=14. 31. Kern KB, et al. Importance of continuous chest compres-

8. Cobb LA, et al. Changing incidence of out-of-hospital ventric- sions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: improved out-

ular fibrillation, 1980-2000. JAMA 2002;288(23):3008-13. come during a simulated single lay-rescuer scenario.

9. Weisfeldt ML, Becker LB. Resuscitation after cardiac arrest: Circulation 2002;105(5):645-9.

a 3-phase time-sensitive model. JAMA 2002;288(23):3035-8. 32. Yu T, et al. Adverse outcomes of interrupted precordial

10. Caffrey SL, et al. Public use of automated external defibrilla- compression during automated defibrillation. Circulation

tors. N Engl J Med 2002;347(16):1242-7. 2002;106(3):368-72.

11. O’Rourke MF, et al. An airline cardiac arrest program. 33. Handley AJ, Handley JA. The relationship between rate of

Circulation 1997;96(9):2849-53. chest compression and compression:relaxation ratio.

12. Valenzuela TD, et al. Outcomes of rapid defibrillation by Resuscitation 1995;30(3):237-41.

security officers after cardiac arrest in casinos. N Engl J Med 34. Dorph E, et al. Quality of CPR with three different ventila-

2000;343(17):1206-9. tion:compression ratios. Resuscitation 2003;58(2):193-201.

13. White RD, et al. Evolution of a community-wide early defib- 35. Sanders AB, et al. Survival and neurologic outcome after

rillation programme experience over 13 years using cardiopulmonary resuscitation with four different chest

police/fire personnel and paramedics as responders. compression-ventilation ratios. Ann Emerg Med 2002;

Resuscitation 2005;65(3):279-83. 40(6):553-62.

14. Larsen MP, et al. Predicting survival from out-of-hospital 36. Holmberg M, et al. Survival after cardiac arrest outside hos-

cardiac arrest: a graphic model. Ann Emerg Med 1993; pital in Sweden. Swedish Cardiac Arrest Registry.

22(11):1652-8. Resuscitation 1998;36(1):29-36.

68 AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 http://www.nursingcenter.com

37. Cobb LA, et al. Influence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation

prior to defibrillation in patients with out-of-hospital ven-

tricular fibrillation. JAMA 1999;281(13):1182-8.

38. Wik L, et al. Delaying defibrillation to give basic cardiopul-

3 HOURS

monary resuscitation to patients with out-of-hospital ven-

Continuing Education

tricular fibrillation: a randomized trial. JAMA 2003;289(11):

EARN CE CREDIT ONLINE

Go to www.nursingcenter.com/CE/ajn and receive a certificate within minutes.

1389-95.

39. Jacobs IG, et al. CPR before defibrillation in out-of-hospital

cardiac arrest: a randomized trial. Emerg Med Australas

2005;17(1):39-45. GENERAL PURPOSE: To provide registered professional

40. Berg RA, et al. Adverse hemodynamic effects of interrupting nurses a summary of the recommendations in the

chest compressions for rescue breathing during cardiopul- 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for

monary resuscitation for ventricular fibrillation cardiac Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardio-

arrest. Circulation 2001;104(20):2465-70.

vascular Care.

41. Bain AC, et al. Multicenter study of principles-based wave-

forms for external defibrillation. Ann Emerg Med 2001; LEARNING OBJECTIVES: After reading this article and taking

37(1):5-12. the test on the next page, you will be able to

42. Mittal S, et al. Comparison of a novel rectilinear biphasic • discuss the changes in the guidelines for the emergency

waveform with a damped sine wave monophasic waveform cardiovascular care of adults.

for transthoracic ventricular defibrillation. ZOLL Investi- • describe the changes in the guidelines for the emer-

gators. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34(5):1595-601.

gency cardiovascular care of children and infants.

43. Hess EP, White RD. Ventricular fibrillation is not provoked by

chest compression during post-shock organized rhythms in TEST INSTRUCTIONS

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2005;66(1):7-11. To take the test online, go to our secure Web site at

44. Redding JS. The choking controversy: critique of evidence www.nursingcenter.com/CE/ajn.

on the Heimlich maneuver. Crit Care Med 1979;7(10):

475-9. To use the form provided in this issue,

45. Ruben H, MacNaughton FI. The treatment of food-chok- • record your answers in the test answer section of the

ing. Practitioner 1978;221(1325):725-9. CE enrollment form at page 72. Each question has only

one correct answer. You may make copies of the form.

46. Guildner CW, et al. Airway obstructed by foreign material:

the Heimlich maneuver. JACEP 1976;5(9):675-7. • complete the registration information and course evalua-

tion. Mail the completed enrollment form and registration

47. Hickey RW, et al. Pediatric patients requiring CPR in the

fee of $24.95 to Lippincott Williams and Wilkins CE

prehospital setting. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25(4):495-501.

Group, 2710 Yorktowne Blvd., Brick, NJ 08723, by

48. Appleton GO, et al. CPR and the single rescuer: at what age January 31, 2009. You will receive your certificate in four

should you “call first” rather than “call fast”? Ann Emerg

Med 1995;25(4):492-4. to six weeks. For faster service, include a fax number and

we will fax your certificate within two business days of

49. Dorfsman ML, et al. Two-thumb vs. two-finger chest com-

receiving your enrollment form. You will receive your CE

pression in an infant model of prolonged cardiopulmonary

resuscitation. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7(10):1077-82. certificate of earned contact hours and an answer key to

review your results. There is no minimum passing grade.

50. Houri PK, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of two-

thumb vs two-finger chest compression in a swine infant DISCOUNTS and CUSTOMER SERVICE

model of cardiac arrest. Prehosp Emerg Care 1997;1(2):

• Send two or more tests in any nursing journal published by

65-7.

Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (LWW) together, and

51. Menegazzi JJ, et al. Two-thumb versus two-finger chest deduct $0.95 from the price of each test.

compression during CRP in a swine infant model of cardiac

arrest. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22(2):240-3. • We also offer CE accounts for hospitals and other

health care facilities online at www.nursingcenter.

52. Whitelaw CC, et al. Comparison of a two-finger versus

com. Call (800) 787-8985 for details.

two-thumb method for chest compressions by healthcare

providers in an infant mechanical model. Resuscitation

PROVIDER ACCREDITATION

2000;43(3):213-6.

LWW, publisher of AJN, will award 3 contact hours for

53. Srikantan SK, et al. Effect of one-rescuer compression/ this continuing nursing education activity.

ventilation ratios on cardiopulmonary resuscitation in

infant, pediatric, and adult manikins. Pediatr Crit Care Med LWW is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing

2005;6(3):293-7. education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s

Commission on Accreditation.

54. Babbs CF, Nadkarni V. Optimizing chest compression to

rescue ventilation ratios during one-rescuer CPR by profes- LWW is also an approved provider of continuing nurs-

sionals and lay persons: children are not just little adults. ing education by the American Association of Critical-

Resuscitation 2004;61(2):173-81. Care Nurses #00012278 (CERP category A), District of

55. Atkinson E, et al. Specificity and sensitivity of automated Columbia, Florida #FBN2454, and Iowa #75. LWW

external defibrillator rhythm analysis in infants and chil- home study activities are classified for Texas nursing con-

dren. Ann Emerg Med 2003;42(2):185-96. tinuing education requirements as Type 1. This activity is

56. Cecchin F, et al. Is arrhythmia detection by automatic exter- also provider approved by the California Board of

nal defibrillator accurate for children?: sensitivity and speci- Registered Nursing, provider number CEP 11749 for 3

ficity of an automatic external defibrillator algorithm in 696 contact hours.

pediatric arrhythmias. Circulation 2001;103(20):2483-8. Your certificate is valid in all states.

57. Samson RA, et al. Use of automated external defibrillators

for children: an update: an advisory statement from the TEST CODE: AJN0207

pediatric advanced life support task force, International

Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation 2003;

107(25):3250-5.

ajn@wolterskluwer.com AJN ▼ January 2007 ▼ Vol. 107, No. 1 69

You might also like

- A Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 3Document124 pagesA Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 3dbryant0101100% (2)

- From The Ashes of Angels 1Document13 pagesFrom The Ashes of Angels 1dbryant0101No ratings yet

- The New England Historical and GenealogiDocument359 pagesThe New England Historical and Genealogidbryant0101No ratings yet

- Game of Life-eBookDocument101 pagesGame of Life-eBookWarrior SoulNo ratings yet

- A Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 1Document124 pagesA Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 1dbryant010150% (2)

- Evanghelia Dupa Iuda CompletaDocument7 pagesEvanghelia Dupa Iuda CompletaciclopulNo ratings yet

- The Narragansett Historical Register Vol 3-4 Part 2Document257 pagesThe Narragansett Historical Register Vol 3-4 Part 2dbryant0101100% (1)

- Mumford Memoirs - Being A Story of The New England Mumfords From The Year 1655 To The Present TimeDocument277 pagesMumford Memoirs - Being A Story of The New England Mumfords From The Year 1655 To The Present Timedbryant0101No ratings yet

- A Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 2Document124 pagesA Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 2dbryant0101No ratings yet

- The Narragansett Historical Register Vol 3-4 Part 1Document453 pagesThe Narragansett Historical Register Vol 3-4 Part 1dbryant0101No ratings yet

- Gov Henry Bull & DescendantsDocument8 pagesGov Henry Bull & Descendantsdbryant0101No ratings yet

- Landis Landes FamilyDocument85 pagesLandis Landes Familydbryant0101No ratings yet

- A Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 4Document123 pagesA Hudson Valley Simmons Family Part 4dbryant0101No ratings yet

- The Narragansett Historical Register Vol 1-2 Part 2Document238 pagesThe Narragansett Historical Register Vol 1-2 Part 2dbryant0101100% (1)

- Ness Family History Part 2Document78 pagesNess Family History Part 2dbryant0101100% (1)

- Gardner-Gardiner Rhode IslandDocument42 pagesGardner-Gardiner Rhode Islanddbryant0101100% (1)

- Moses Barber 1652-1733 of South Kinston Rhode IslandDocument149 pagesMoses Barber 1652-1733 of South Kinston Rhode Islanddbryant0101100% (3)

- Ness Family History Part 4Document75 pagesNess Family History Part 4dbryant0101100% (1)

- Record of The Rust Family Part 1Document189 pagesRecord of The Rust Family Part 1dbryant0101No ratings yet

- Record of The Rust Family Part 2Document189 pagesRecord of The Rust Family Part 2dbryant0101100% (1)

- Ness Family History Part 1Document78 pagesNess Family History Part 1dbryant0101100% (1)

- Nellis Family HistoryDocument247 pagesNellis Family Historydbryant0101No ratings yet

- Ma Tri Lineal Descendants of Catherine Allison AnsleyDocument35 pagesMa Tri Lineal Descendants of Catherine Allison Ansleydbryant0101No ratings yet

- Record of The Rust Family Part 3Document187 pagesRecord of The Rust Family Part 3dbryant0101100% (2)

- Ness Family History Part 3Document78 pagesNess Family History Part 3dbryant0101No ratings yet

- Bouck of Schoharie & OntarioDocument231 pagesBouck of Schoharie & Ontariodbryant010175% (4)

- John Caspar Stoever of PennaDocument10 pagesJohn Caspar Stoever of Pennadbryant0101100% (1)

- Chronicles of The Family BakerDocument414 pagesChronicles of The Family Bakerdbryant0101100% (2)

- An Authentic History of Lancaster County Part 2Document305 pagesAn Authentic History of Lancaster County Part 2dbryant0101100% (6)

- An Authentic History of Lancaster County Part 1Document287 pagesAn Authentic History of Lancaster County Part 1dbryant0101No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017Document54 pagesClinical Practice Guidelines - 2017Cem ÜnsalNo ratings yet

- Maxillary Sinus Approaches-1Document23 pagesMaxillary Sinus Approaches-1Ahmed KhattabNo ratings yet

- CV For Website 2019Document2 pagesCV For Website 2019api-276874545No ratings yet

- Quarter 3 Study Guide: Digestive SystemDocument3 pagesQuarter 3 Study Guide: Digestive SystemChristina TangNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument4 pagesCase StudyTariq shahNo ratings yet

- Marijuana: A Medicine For CancerDocument11 pagesMarijuana: A Medicine For CancerXylvia Hannah Joy CariagaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Blood TransfusionDocument10 pagesPediatric Blood TransfusionELISION OFFICIALNo ratings yet

- TraumaAirway Management - ValDocument36 pagesTraumaAirway Management - ValValerie Suge-MichiekaNo ratings yet

- Snake Bite Phenomenon - Dr. TrimaharaniDocument84 pagesSnake Bite Phenomenon - Dr. TrimaharaniIendpush Slalu100% (1)

- Microbiological Quality of Non-SterileDocument5 pagesMicrobiological Quality of Non-SterilePaula BelloNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Physiology MCQDocument11 pagesCardiovascular Physiology MCQJessi ObibiNo ratings yet

- Herbal Antibiotics 1999 - BuhnerDocument676 pagesHerbal Antibiotics 1999 - BuhnerJoyce-Bea Vu50% (4)

- 13 Areas of AssessmentDocument3 pages13 Areas of AssessmentSoleil MaxwellNo ratings yet

- Pembanding1 Phanthom ReproDocument13 pagesPembanding1 Phanthom ReproEva SavitriNo ratings yet

- HSG PresentationDocument18 pagesHSG Presentationashikin92No ratings yet

- Endocrine of The Pancreas: Eman Alyaseen 20181081Document8 pagesEndocrine of The Pancreas: Eman Alyaseen 20181081ÂmoOł ÀhmdNo ratings yet

- Case Study 103Document8 pagesCase Study 103Jonah MaasinNo ratings yet

- COVID y RiñonesDocument73 pagesCOVID y RiñonesSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- CM Sputum Examination Ocfemia Eliazel G.Document41 pagesCM Sputum Examination Ocfemia Eliazel G.eliazel ocfemiaNo ratings yet

- Basic and Clinical Pharmacology 12th Edition-Bertram Katzung Susan Masters Anthony Trevor-290-296 PDFDocument7 pagesBasic and Clinical Pharmacology 12th Edition-Bertram Katzung Susan Masters Anthony Trevor-290-296 PDFalinamatei1000000No ratings yet

- Starting Intravenous LinesDocument7 pagesStarting Intravenous LinesPhillip CharlesNo ratings yet

- Chemical Peel Guidelines PDFDocument1 pageChemical Peel Guidelines PDFHasan MurdimanNo ratings yet

- Daily-Inpatient-Care-Checklist 112118 346713 284 45189 v1Document5 pagesDaily-Inpatient-Care-Checklist 112118 346713 284 45189 v1Andrew McGowanNo ratings yet

- Multi-Specialty Hospital: Ram Sharada Healthcare Pvt. LTDDocument48 pagesMulti-Specialty Hospital: Ram Sharada Healthcare Pvt. LTDsubhash goelNo ratings yet

- English KakakDocument5 pagesEnglish Kakakjasma yuliNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Cardiac Enzymes:: Test: SGOTDocument4 pagesInterpretation of Cardiac Enzymes:: Test: SGOTMohammed AbdouNo ratings yet

- IMF Screw Set. For Temporary, Peri Operative Stabilisation of The Occlusion in AdultsDocument12 pagesIMF Screw Set. For Temporary, Peri Operative Stabilisation of The Occlusion in AdultsAnonymous LnWIBo1GNo ratings yet

- BSA Creat Clearance Calculation OriginalDocument2 pagesBSA Creat Clearance Calculation Originalstrider_sdNo ratings yet

- BF Builders and Construction Corporation Hiv/Aids Workplace Policy and ProgramDocument4 pagesBF Builders and Construction Corporation Hiv/Aids Workplace Policy and Programglenn dalesNo ratings yet

- Homeopathic Care, Don Hamilton DVM PDFDocument48 pagesHomeopathic Care, Don Hamilton DVM PDFBibek Sutradhar0% (1)