Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Silence

Uploaded by

Peter.MillingtonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Silence

Uploaded by

Peter.MillingtonCopyright:

Available Formats

Silence

There is breathing in and breathing out. Or is that too simple? Perhaps if things were that simple our lives would be different. And perhaps our lives are not different because they are complex. We cannot remain child-like. Though there have been occasions when I have wished for the simplicity of childhood: wished for its comforts. There is growing up. There is the realisation that the world is awkward and sometimes falls short of expectation. How do things get tangled up and lost? If I could answer that I would. If I could tell you why things turn out as they do I would write you a book. I cannot. It perplexes me. Now there are days when I feel everything that once made sense has been turned upside down. It seems the world has lost its balance. You wonder how much further things can go before it becomes clear they are going nowhere at all. I look about and I see so many faces. I see them stunned and anxious in shopping malls. I see them lost and confused in rail stations. I wonder about the dreams I have been sold: the dreams that beguile and whisper and yet leave me sharp and hollow. And I wonder about the casualties: who are everywhere. The casualties of the wars fought on streets, through TV screens, in living rooms and bedrooms.

I breathe in and I breathe out: just for this morning I let it be that simple. It is a raw, spring morning. The sun lies low on the horizon. It seems to struggle to rise higher. Bands of cloud, grey and cotton-like, drift over the spires and gables of the old city: over rail tracks and waterfront and office towers. A strange light fills in spaces and falls across my hands. I sit on a train. It has just crossed a bridge. How I remember that bridge. Once I lay awake at night and listened as trains rattled its steel girders. Their sound made me think of rivers: rivers of clear air flowing down from the north. I notice trees in a park. They are just beginning to show their leaves. Their grey-brown bark speaks of something resilient: something strong.

And that park seems wound into my being. Once I held your hand and walked along its gravel paths with you: also on spring days when the leaves were just struggling out onto those same branches. When the breeze could still be sharp and the clouds would be high and sailing in from the sea. Then your hand was smaller. Your fingers clung tightly onto mine. Your steps were still tentative. The world was all new to you. Then I was a father and you were a son.

I am on my way to the airport. Already I sense the heavy smell of air fuel fumes. I hear flights being called. In a couple of hours wheels will bite into asphalt and there will be the thrust of engines and I will be gone again: just a brief stay for a father to visit a son: a father and son with different lives between them. I remember this city because it is there you first grew into life. What can I say except sometimes those days come back with such clarity it seems I am still immersed in them? Perhaps that is how life is: it is memories and moments. We are those memories and moments and cannot escape their sweet or bitter tastes.

I remember clearly the winter of 1991: the winter of the first Gulf War. Wars end and wars never end. Who can say what the reality is behind the images on a TV screen? Do we ever really know how close we come to defeat or how easily we are deceived by an apparent victory? Then we lived in a small third floor apartment west of the rail station: in the Zeeheldenbuurt. Amsterdam 1013 MP Your mother and I first saw that apartment on a September night. Along the quay, still Linden trees shadowed pavements. The water was black and still. In the harbours lights from tankers and freighters glowed and the moon, full, gave everything a subtle, elusive light. That was shortly after you were born. Perhaps I remember that winter because of the cold. It was one of the coldest winters in all the time I lived there. The cold started in mid December and lasted until March. I see us, you, your mother and I walking along the Haarlemmerdijk early in the New Year. It is a Sunday afternoon. We have just been to the American Hotel to drink hot chocolate and eat pancakes. They are not

2

easy days. Sometimes money is tight and we are still young. This has been a special treat. Fluorescent light, reds and greens and pinks from a small cinema spill onto the dark grey pavement. The sky is blue like an ocean. There are thin, amber lined clouds to the northwest. You walk between your mother and I. A down coat with the hood pulled tight against your face, keeps you warm. Around your neck is a knitted yellow scarf. We leave the street and cross the plein. There are empty benches under bone-thin trees. The benches are deserted. In summer old Turkish men sit and play chess on them, talking and gesticulating and fingering their prayer beads. In the afternoon light the stone of the Willemspoort is heavy and grey. A sharp wind kicks up dust and old papers. We cross under the rail bridge where the tram wires dip and weave. The tiny Moroccan supermarket is closed. Already the lights in buildings are coming on. They are warm. You pull free of my hand and run ahead. That knitted yellow scarf blows out behind you. Your steps are still small and uncertain. Still you run: determined and cautious and persistent. That winter I had to get up early for work. Those dark mornings, I walked around the apartment as quietly as I could. Sometimes, I simply stood, drinking a cup of black coffee and staring out the window. Nearly always, it was still. Occasionally a solitary motorcyclist or early morning taxi crossed the bridge heading west. Perhaps someone had an early flight and needed to be in the airport. There was the Harbour-Service on the junction of the bridge and outer quay. If the bridge was closed, the red and white barriers stretched into a sky, dark and broken with stars. There was something comforting about the light seeping out from under closed blinds. Sometimes I thought of the men and women who worked there. I imagined them sitting watching for boats and barges coming into the city. They might be sleepy and perhaps on their desks were half-drunk cups of coffee, stubbed out Caballero cigarettes and newspapers. On the street the air cut like a knife. I still feel the cold metal of the bicycle rack beneath my fingers. Still I hear the rattle of the lock as I loosen it. The smell of bread from a nearby bakery drifts on the freezing air. A first tram screeches against rails as it rounds a corner. And along the quay and on the square the trees are spiny and black. That winter the water along the quay was iced over. Every morning, just after sunrise, patrol boats broke the ice open only for it to close again as sun fell. It froze into strange vein-like patterns.

I breathe in this morning because as the train leaves the city memory surfaces with such subtle power I am made to feel helpless. In the passing reflections of the train window I see that neighborhood again: the dusty little plein with its kitsch caf and sad shops. Behind the apartments is the Prinseneiland, all winding streets, converted warehouses, and moored summer boats. I see the linden trees full in late spring. Their blooms are blown over the pavements. Or it is an October evening and the streets are damp after a passing shower. Clouds break in Vermeer-like curls. Over the streets a burnished sunlight falls. It mixes with the yellow and green-fading leaves; it catches the ripples of the water and flashes, suddenly brown and heavy.

It was that winter it snowed heavily. I came out of work one afternoon to find the city white. Things felt buried. There were trams moving but their motion was silent. Soft, thick flakes floated against my face and clung to my jacket. Bodies ghosted past or disappeared through the glass doors of department stores. I was to collect you at the kindergarten. My bicycle was in the lock-up at the rail station, so I went there. Then I began to make my way across the city. It was difficult. The thin tyres slipped and slid and I could hardly see in front of me. At times I had to get down and walk. Over canals and narrow, near deserted streets I moved. I imagined my progress being traced out in a dark line. And I though above those pressing snow clouds, it was bright. In the high air, above the city, the sun shone and aircraft flew and looking down no one knew what a different world it was below. I crossed the whited-out park and passed through the tunnel under the rail tracks. Then I was making my way past the brown-bricked three storeys. In the kindergarten it was quiet. The door to the playroom was open. At first I did not see you. Only the room, with its wooden floorboards and high windows filled with some fantastic light. Then you were there. To my left and sitting waiting for me, your red and blue and yellow school bag between your feet. I heard the muffled laugh of a teacher from a nearby room. The smell of freshly opened clementines lingered on the air, their sweet, citric scent reaching back into my own childhood.

On the pavement you looked about in wonder. The street to the apartment seemed long and lost in white. Gables and windows were disappearing into the incessantly falling flakes. We climbed the stairs to the apartment. It was barely 3 oclock yet somehow within the building walls it was dark and grey. Perhaps it was always like that and only then it struck me. There was always something sad and mediocre about that building. In the living room I switched on the TV. A stream of images from the Persian Gulf drifted into the family space: briefings and infrared images and the heat of desert. I searched for cartoons or childrens programming but there were only talk-shows and adverts and soaps. Through the window the sky was steely-grey. Snow just kept coming down. The immediate world seemed be coming to a standstill and the city was just a speck, a flake drifting through a white universe. I went to the kitchen to get a glass of water. When I returned you were standing against the windowsill and staring out. There were little pools of water at your feet where the snow stuck to your jacket had fallen after melting. So I sat down on the couch. I did not tell you to take your jacket off, I just sat there, slowly sipping the water and watching you. Your face was pale and your blond hair shone in the light coming through the glass. And I wondered where your mother was. Maybe she was in a department store buying clothes or drinking coffee with a friend. I did not know. With the snow falling, the murmur of the TV, the long weeks of cold, I suddenly felt alone. I felt alone the way I felt alone as a child. Before my eyes is a picture-postcard semi-detached. There is a driveway and a well-tended garden. Trees line a long, quiet avenue. There are paperbacks and model aircraft on a bedroom table. There is a tennis racket and football boots and a school uniform hung over an open wardrobe door: and my own fathers face. He sits at the wheel of his car. His dark overcoat reflects of the glass, and his hands, in driving gloves grip the hard, leather covered steel. We have stopped on a deserted mountain road. The passenger door of the car is open and I stand at the roadside looking down into a valley. In my brown, tweed overcoat and scarf and red hat I focus my vision: like a soldier assessing enemy territory. I see a thinly-iced river. First snow lies on the ground. To the west dark, clumps of coniferous cover hillsides. I hear shoes on cold asphalt: and look back. My father has opened the driver door and steps to the front wing. He takes off his driving gloves and lights a cigarette. The blue smoke hangs in the cold air. From the car radio a monotone voice concludes a news report. The tinny jingle of an advert follows. It is the first time I see that look in my fathers eye: a look that says things

should be different but they are not. In it is some unspoken betrayal. I am almost felled by his silent resentment carried on the winter air. I wondered again where your mother was. It felt like something was stuck: something was knotted and dark. There was this city and this apartment, this snow. Some things are written into the fabric of a moment. Between each fall of a snowflake came that morning. Your mother and I are waiting on a taxi to take us from the hospital to home. It is a January day: with a pale sun over damp earth and naked trees. The blue and yellow of a train moves in from the east. High-rises and offices reach into the raw winter air. Your eyes are closed. When they open they look so blue. They have a look of aquamarine and blink as though the world is yet too new and too much to take in. That afternoon the snow fell and fell. It fell on the ice covering the water, on the pavement, on the bridge, on the handlebars of bicycles. It fell all over the city. When your mother came home you were sitting at the table. There was a half-eaten plate of spaghetti and a glass of orange juice in front of you. The wall lamp glowed and softened the room in light. There was an open bottle of wine. You got up to receive the kiss she bent to offer. You began to explain when she asked how your day had been. I did not hear all you said because I was already in the kitchen: looking out over the bridge and across the water. The sky had turned murky and amber and in the halo of streetlights the snow fell darkly. Along the quay the Linden trees were not full or shadowed and the only lights burning were the lights from ghosted apartment blocks. I saw it then. Somewhere in a room a man sleeps. Now that man awakes. It is evening in a strange city. A radio plays low from an adjacent room: maybe it is a jazz tune or an aria. The man thinks of something small and not obviously significant: a meal to be eaten, a letter he would like to read or simply a voice calling out a name. He glimpses his face in a mirror. His hair has greyed. His shoulders stoop a little more and there is a stiffness in his limbs. And he recalls. An afternoon stopped on a quiet mountain road. He recalls a Sunday with a sky blue like an ocean: the taste of pancakes and hot chocolate. A boy runs under weaving tram wires. A boy runs into the snow covering gables and losing a street in white. The smell of clementines comes back to him.

Silence, he is wounded by the silence hanging in evening air. The casualties of the unseen wars are everywhere. He breathes in and then he breathes out.

Copyright Peter Millington

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Installation Guide For GRE PipingDocument32 pagesInstallation Guide For GRE PipingAnh Võ100% (5)

- Strategic Supply Chain ManagementDocument16 pagesStrategic Supply Chain ManagementKknow Ddrug100% (3)

- 2018 - PWC, Assessing of Tunnel Costs of Rail ProjectsDocument375 pages2018 - PWC, Assessing of Tunnel Costs of Rail ProjectslucaNo ratings yet

- Study of A Single Effect EvaporatorDocument11 pagesStudy of A Single Effect Evaporatormahbub133267% (6)

- Scope of The Railway ProjectDocument35 pagesScope of The Railway ProjectTAHER AMMARNo ratings yet

- CementDocument40 pagesCementanteid3100% (1)

- Transport PolicyDocument7 pagesTransport PolicyandeepthiNo ratings yet

- Layout of Compact Grade Separated JuncitonDocument31 pagesLayout of Compact Grade Separated JuncitonWahyu TamadiNo ratings yet

- DILG Memo - Circular 20111014 3c8ad8f9ca PDFDocument1 pageDILG Memo - Circular 20111014 3c8ad8f9ca PDFOhmar Quitan CulangNo ratings yet

- Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and The Decline of The American DreamDocument30 pagesSuburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and The Decline of The American DreamFernando Abad100% (1)

- Parts Catalog Cummins, 6LTAA8.9G2 - ESN 82312099 - CPL 3079-52Document1 pageParts Catalog Cummins, 6LTAA8.9G2 - ESN 82312099 - CPL 3079-52Hardiansyah SimarmataNo ratings yet

- TMI: Trek To Harishchandragad Via Nali Chi Vaat On 5th and 6th Jan '13Document4 pagesTMI: Trek To Harishchandragad Via Nali Chi Vaat On 5th and 6th Jan '13swaranjali moreNo ratings yet

- Padernal-BSA-1A-SW-Accounts ReceivableDocument4 pagesPadernal-BSA-1A-SW-Accounts ReceivableFly ThoughtsNo ratings yet

- Mermaid CommanderDocument2 pagesMermaid CommanderFatin AfraNo ratings yet

- Test Ces Clasa A 7Document2 pagesTest Ces Clasa A 7andreifiuNo ratings yet

- The New P 410 LA 6x2 MNA With Opticruise: Scania Haulage TrucksDocument2 pagesThe New P 410 LA 6x2 MNA With Opticruise: Scania Haulage TrucksCristian ChiruNo ratings yet

- Un Ece 36 PDFDocument75 pagesUn Ece 36 PDFRodrigo TaveiraNo ratings yet

- Emea Cat Mo Wheel Bearings Catmo1802 2018-2019 en HQDocument1,164 pagesEmea Cat Mo Wheel Bearings Catmo1802 2018-2019 en HQJharomar BatacNo ratings yet

- Adventure Afrika - Issue 20 (Jun 2022) .Freemagazines - TopDocument84 pagesAdventure Afrika - Issue 20 (Jun 2022) .Freemagazines - TopFoxy BusinessNo ratings yet

- 165-Panama Circular Immersion SuitsDocument2 pages165-Panama Circular Immersion SuitsNeelakantan SankaranarayananNo ratings yet

- 2 Maintenance Schdule Blow Room, Carding DecDocument15 pages2 Maintenance Schdule Blow Room, Carding DecBHASKAR MITRANo ratings yet

- In The Neighborhood I: Upn, Pasión Por Transformar VidasDocument24 pagesIn The Neighborhood I: Upn, Pasión Por Transformar VidasNirvana HornaNo ratings yet

- SCM - An OverviewDocument50 pagesSCM - An OverviewPooja NagleNo ratings yet

- Market Study FormDocument6 pagesMarket Study FormJc IbarraNo ratings yet

- Cox Diesel Marine Tech Spec 2.2 July 2019Document8 pagesCox Diesel Marine Tech Spec 2.2 July 2019david rivasNo ratings yet

- Golf VI GTI 2.0Document19 pagesGolf VI GTI 2.0javiNo ratings yet

- NMS Complete EnglishDocument17 pagesNMS Complete EnglishthamindulorensuNo ratings yet

- DOST Tour ReflectionDocument2 pagesDOST Tour ReflectionChristian EstebanNo ratings yet

- InstructivoDocument5 pagesInstructivoPapeleria-ciber LoscompasNo ratings yet

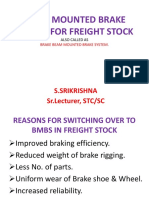

- BMBS For Freight Stock-SKDocument25 pagesBMBS For Freight Stock-SKSoumen BhattaNo ratings yet