Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CISCO - Connected and Sustainable Energy WP 0919 Final Presentation

Uploaded by

Tozaru Elena-AlinaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CISCO - Connected and Sustainable Energy WP 0919 Final Presentation

Uploaded by

Tozaru Elena-AlinaCopyright:

Available Formats

White Paper

Connected and Sustainable Energy

Written specifically for Connected Urban Development Global Conference 2008Amsterdam

Author Wes Frye Cisco Internet Business Solutions Group

White Paper

Connected and Sustainable Energy

About Connected Urban Development

Connected Urban Development (CUD) is a public-private partnership program focused on innovative use of information and communications technology (ICT) to make knowledge, people, traffic, and energy flow more efficiently. This increased efficiency enhances how people experience urban life, streamlines the management of cities, and decreases the urban environmental footprint. The programs main success elements are: Measuring CO2 emissions reduction resulting from operational implementation of CUD projects within cities. Demonstrating the positive impact of ICT and broadband connectivity on climate change Developing relevant thought leadership and replicable methodologies allowing CUD partner cities to learn from each other and share their experiences and best practices with cities around the world The initial scope of the program includes five major areas of focus: Connected and Sustainable Work Connected and Sustainable Mobility Connected and Sustainable Energy Connected and Sustainable Buildings Connected and Sustainable ICT Infrastructure

Context

Cities around the world are realizing that energy consumed by buildings and homes is the leading cause of global-warming emissions. This includes electricity and fossil fuel used to light, heat, and power our homes, apartments, office buildings, and factories. In fact, New York City estimates that energy usage causes roughly 80 percent of its globalwarming emissions and more than 40 percent of locally generated air pollution. By 2015, New York City estimates it will be pumping an additional 4.6 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere each year.1 The cause is a growing demand for energy, combined with aging electricity infrastructure. New York Citys electricity demand is forecast to grow 44 percent by 2030. Many plants that generate electric power are more than 30 years old (with outdated technologies), use 30 to 60 percent more fuel, and produce several times the air pollution of newer plants to generate the same amount of electricity.

1. PlaNYC, Office of Mayor Bloomberg, 2008, page 101.

White Paper

But energy poses additional challenges for city leaders. Our demand for electricity continues to grow, increasing consumer costs. New York City estimates that by 2015, the citys annual electricity and heating bill will grow by $3 billiontranslating into annual energy bills that are $300 to $400 higher per household. By 2030, New York City forecasts electricity costs will rise 60 percent above todays. Clearly, city leaders working to reduce their impact on climate change need to focus carefully on how energy is generated, distributed, and consumed throughout their city. What can be done? Leading cities are creating dedicated ministries and departments to develop integrated strategies to meet our growing demand for energy while mitigating its impact on climate change. There is no easy solution, and cities must focus both on reducing energy consumption of residents and industry while accelerating greener energy-generation plants. This paper presents an overview of emerging solutions for city leaders to reduce electricity consumption, produce greener energy with lower carbon emissions, and improve the reliability of the electric grid.

The Electric Grid

Most of the worlds electricity delivery system or grid was built when energy was relatively inexpensive. While minor upgrades have been made to meet increasing demand, the grid still operates the way it did almost 100 years agoenergy flows over the grid from central power plants to consumers, and reliability is ensured by maintaining excess capacity. The result is an inefficient and environmentally wasteful system that is a major emitter of greenhouse gases, consumer of fossil fuels, and not well suited to distributed, renewable solar and wind energy sources. In addition, the grid may not have sufficient capacity to meet future demand. Several trends have combined to increase awareness of these problems, including greater recognition of climate change, commitments to reduce carbon emissions, rising fuel costs, and technology innovation. In addition, recent studies support a call for change: Power generation causes 25.9 percent of global carbon (CO2) emissions.2 CO2 emissions from electricity use will grow faster than those from all other sectors through 2050.3 Forecast demand for electricity may exceed projected available capacity in the United States by 20154 (see Figure 1).

2. IPCC, 2007. 3. Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, 2006. 4. Long-Term Reliability Assessment 20072016, North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), October 2007.

White Paper

Figure 1. Projected Electricity Capacity versus Demand in the United States 1,100 1,050 Thousands of Megawatts 1,000 950 900 850 800 750 700 650 600 550 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 Year

Source: NERC, 2008; Cisco IBSG, 2008

Projected Potential Capacity Projected Available Capacity High Demand Projection Low Demand Projection Historic Demand

Given this information, governments and regulators, utility companies, and technology firms are rethinking how the electricity grid should look. Already, utility companies and governments around the world are launching efforts to: Increase distributed solar and wind power generation to increase the electrical supply without additional greenhouse gas emissions Use plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) to generate and consume electric power intelligently Sequester (scrub and store) the carbon from coal plant emissions Use demand management to improve energy efficiency and reduce overall electricity consumption Monitor and control the energy grid in near-real time to improve reliability and utilization, reduce blackouts, and postpone costly new upgrades For all of these effortssolar and wind plants, PHEVs, active home-energy management, and grid monitoringto work together in one integrated system, a new level of intelligence and communication will be required. For example: Rooftop solar panels need to notify backup power generators within seconds that approaching clouds will reduce output. The grid needs to notify PHEVs about the best time to recharge their batteries. Utility companies need to communicate with and control appliances such as refrigerators and air conditioners during periods of peak electricity demand.

White Paper

Factory operators must know the cost of electric power every few minutes to manage their energy use economically. Homeowners need to become smart buyers and consumers of electricity by knowing when to adjust thermostats to optimize energy costs. Unfortunately, these activities cannot be achieved with the current energy grid. Todays electric infrastructure simply cannot coordinate and control all the systems that will be attached to it. A new, more intelligent electric system or Smart Grid is required that combines information technology (IT) with renewable energy to significantly improve how electricity is generated, delivered, and consumed (see Figure 2). A Smart Grid provides utility companies with near-real-time information to manage the entire electrical grid as an integrated systemactively sensing and responding to changes in power demand, supply, costs, and emissionsfrom rooftop solar panels on homes, to remote, unmanned wind farms, to energy-intensive factories. A Smart Grid is a major advance from today, where utility companies have only basic information about how the grid is operating, with much of that information arriving too late to prevent a major power failure or blackout.

Figure 2. Traditional Roles Are Reversed with a Smart GridConsumers Become Producers, and Information and Electricity Flow in Both Directions

Smart Grid Diagram

Low-energy Home with Microgeneration Device

Electricity Flow Information Flow

Energy Storage

Grid Operation Center

Coal Sequestration

Large-scale Renewable Generation Building as Power Plant Nuclear Power Plant

Distribution Grid Sensors

Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles High-voltage DC

Electric Public Transportation

Smart Grid Community (Energy Co-ops)

Emissions Monitoring

Source: Cisco IBSG, 2008.

White Paper

Components of a Smart Grid

A Smart Grid comprises three major components: 1) demand management, 2) distributed electricity generation, and 3) transmission and distribution grid management.

1) Demand Management: Reducing Electricity Consumption in Homes, Offices, and Factories

Demand management works to reduce electricity consumption in homes, offices, and factories by continually monitoring electricity consumption and actively managing how appliances consume energy. It consists of demand-response programs, smart meters and variable electricity pricing, smart buildings with smart appliances, and energy dashboards. Combined, these innovations allow utility companies and consumers to manage and respond to variances in electricity demand more effectively. Demand responseDuring periods of peak energy use, utility companies send electronic alerts asking consumers to reduce their energy consumption by turning off non-essential appliances. When the Smart Grid is fully developed, alert signals will be automatically sent to appliances, eliminating the need for manual intervention. If enough consumers comply with this approach, the reduction in power consumption could be enough to keep a typical utility company from building an additional power plantthe most expensive asset utility companies operate.5 To increase the number of consumers who comply, utility companies may offer cash payments or reduce consumers electric bills. Smart meters and variable pricingTodays electricity prices on the wholesale market are volatile because they are determined by supply and demand, as well as by situations that depend on generation capacity, fuel prices, weather conditions, and demand fluctuations over time. On average, off-peak prices at night are 50 percent less than prices during the day. During demand peaks, prices can be many times greater than those of off-peak periods. Despite price fluctuations in wholesale markets, most retail consumers are currently charged a flat price for electricity regardless of the time of day or actual demand. Consumers, therefore, have no visibility into when energy is in short supply, and have little incentive to lower their energy use to reduce their energy bill while helping utility companies meet demand. To remedy this situation, utility companies are now replacing traditional mechanical electric meters with smart meters. These new devices allow utility companies to monitor consumer usage frequently and, more important, give customers the ability to choose variable-rate pricing based on the time of day. By seeing the real cost of energy, consumers can respond accordingly by shifting their energy consumption from high-price to low-price periods.

5. GridWise Demonstration Project Fast Facts, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, December 2007.

White Paper

This process, called load shifting or load shedding, can have the joint benefit of reducing costs for typical consumers while lowering demand peaks for utility companies. Smart buildings with smart appliancesFor decades, architects have designed passive, energy-efficient systems such as multi-pane windows, better insulation, and appliances that use less energy and are more friendly to the environment. Recent technology innovations now allow active monitoring and reduction of the energy consumed by appliances. Building control systems that manage various appliances heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC), and lightingalso are converging onto a common IT infrastructure that allows these devices to communicate with each other to be more efficient and reduce waste. A manager of more than 100 government buildings, for example, was able to reduce energy consumption nearly 20 percent and save tens of millions of dollars annually simply by ensuring that his building systems were operating properly.6 This meant heaters and air conditioners were not running simultaneously, steam traps were not leaking, and ventilation fans were operational. Energy dashboards and controllersOnline energy dashboards and controllers, already being developed, will provide real-time visibility into individual energy consumption and generation while automatically turning major appliances on and off, and adjusting thermostats to reduce energy use and lower CO2 emissions. A recent university study found that simple dashboards can encourage occupants to reduce energy use in buildings by up to 30 percent.7 Similarly, homeowners will have passive displays, such as the Ambient Orb, a countertop device that glows red when electricity costs are high and green when costs are low, to make the cost of energy more transparent for consumers. Green ITElectricity requirements for IT equipment, such as computers, printers, servers, and networking equipment, vary widely across building types. For example, restaurants, warehouses, and retail stores have much lower power consumption for IT equipment than office buildings and data centers. For office buildings, IT typically accounts for more than 20 percent of the energy used, and up to 70 percent in some offices.8 As HVAC and lighting systems become more efficient and the volume of IT gear in smart buildings grows, the portion of building energy use attributable to IT will continue to increase. Smart-building solutions that improve the energy efficiency of IT equipment include network-based power management, network printers, server virtualization, the procurement of energy-efficient equipment, and telecommuting.

6. State of Missouri, Dave Mosby, Director of the Division of Facilities Management and Design and Construction (DFMDC), 2007. 7. Oberlin College, 2005, http://www.oberlin.edu/dormenergy/news.htm 8. Cisco IBSG, 2008.

White Paper

2) Distributed Electricity Generation: Accelerating Widespread Installation of Renewable Energy Sources

Renewable energy using microgeneration devicesAlready, some homes and offices find it cost-effective to produce some or all of their own electricity using microgeneration devicessmall-scale energy-generation equipment designed for use in homes and offices. Microgeneration devices primarily include rooftop solar panels, wind turbines, fossil fuel cogeneration plants, and soon, PHEVs that can generate electricity for sale back to the grid. These devices are becoming more affordable for residential, commercial, and industrial customers. Depending on the technology type and operating environment, microgeneration devices can be cost-competitive compared to conventional generation methods. Even so, widespread adoption of these technologies will require government incentives, public awareness campaigns, and further technology development. When fully developed, a Smart Grid will allow owners of microgeneration devices and other energy-generation equipment to sell energy back to utility companies for a profit more easily. When this happens, consumers become an active part of the grid rather than being separate from it. Despite the obvious benefits, renewable energy generation also provides a unique challenge: wind and solar power are much more variable than conventional power plants. For example, when the wind stops blowing or the sky becomes overcast, these systems stop generating power, creating shortages in the electrical grid. To compensate, utility companies must be able to anticipate these shortages in time to start up conventional power plants to temporarily offset the energy deficit. The Smart Grid will integrate weather reports, real-time output monitoring, and grid-load balancing to respond to this variability proactively. Storage and PHEVsUntil recently, pumped water storage was the only economically viable way to store electricity on a large scale. With the development of PHEVs and electric cars, new opportunities will become available. For example, car batteries can be used to store energy when it is inexpensive and sell it back to the grid when prices are higher. For drivers, their vehicles would become a viable means to arbitrage the cost of power, while utility companies could use fleets of PHEVs to supply power to the grid to respond to peaks in electricity demand. Smart Grid communitiesA few forward-looking cities and communities, such as Boulder, Colorado in the United States, are exploring the formation of energy cooperatives that pair corporations and government facilities with residential homes to self-manage some of their energy needs.10

9. City of Boulder, Colorado, 2008.

White Paper

For example, business buildings and government facilities consume electricity primarily during normal working hours, while homes use it mostly during morning and evening hours. By aggregating the total energy consumption, energy co-ops can smooth some of the variability in total energy demand. Backup and alternative power sources in buildings could also provide power to homes during off-business hours, while homes could provide power to businesses during working hours. While the concept is yet to be fully proven, energy co-ops may offer a reasonable alternative to utility-only power, especially if local regulations do not yet require utility companies to buy back surplus power generated locally.

3) Transmission and Distribution Grid Management

Utility companies are turning to IT solutions to monitor and control the electrical grid in real time. These solutions can prolong the useful life of the existing grid, delaying major investments needed to upgrade and replace current infrastructure. Until now, monitoring has focused only on high-voltage transmission grids. Increasing overall grid reliability and utilization, however, will also require enhanced monitoring of medium- and low-voltage distribution grids. Grid monitoring and controlExpensive power outages can be avoided if proper action is taken immediately to isolate the cause of the outage. Utility companies are installing sensors to monitor and control the electrical grid in near-real time (seconds to milliseconds) to detect faults in time to respond. These monitoring and control systems are being extended from the point of transmission down to the distribution grid. Grid performance information is integrated into utility companies supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems to provide automatic, near-real-time electronic control of the grid. Grid security and surveillanceMany of the assets used to generate and transmit electricity are vulnerable to terrorist attacks and natural disasters. Substations, transformers, and power lines are being connected to data networks, allowing utility companies to monitor their security using live video, tamper sensors, and active monitoring.

Smart Grid Benefits

A Smart Grid that incorporates demand management, distributed electricity generation, and grid management allows for a wide array of more efficient, greener systems to generate and consume electricity. In fact, the potential environmental and economic benefits of a Smart Grid are significant. A recent study, sponsored by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, provided homeowners with advanced technologies for accessing the power grid to monitor and adjust energy consumption in their homes. The average household reduced its annual electric bill by 10 percent.10

10. Department of Energy Putting Power in the Hands of Consumers through Technology, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, January 2008, http://www.pnl.gov/topstory.asp?id=285

White Paper

If widely deployed, this approach could reduce peak loads on utility grids up to 15 percent annually, which equals more than 100 gigawatts, or the need to build 100 large coal-fired power plants over the next 20 years in the United States alone. This could save up to $200 billion in capital expenditures on new plant and grid investments, and take the equivalent of 30 million autos off the road.11 Similarly, governments are trying to revitalize economic growth by attracting industries that will produce and build the Smart Grid. According to former U.S. Vice President Al Gore, Just as a robust information economy was triggered by the introduction of the Internet, a dynamic, new, renewable energy economy can be stimulated by the development of an electranet or Smart Grid.12

Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Worldwide demand for electric energy is expected to rise 82 percent by 2030.13 Unless revolutionary new fuels are developed, this demand will be met primarily by building new coal, nuclear, and natural gas electricity-generation plants. Not surprisingly, world CO2 emissions are estimated to rise 59 percent by 2030 as a result.14 The Smart Grid can help offset the increase in CO2 emissions by slowing the growth in demand for electricity. A Smart Grid will: Enable consumers to manage their own energy consumption through dashboards and electronic energy advisories. More accurate and timely information on electricity pricing will encourage consumers to adopt load-shedding and load-shifting solutions that actively monitor and control energy consumed by appliances. In deregulated markets, allow consumers to use information to shift dynamically between competing energy providers based on desired variables including energy cost, greenhouse gas emissions, and social goals. One possibility is an eBay for electricity where continual electronic auctions match energy consumers with producers. Users could include utility companies, homeowners with rooftop solar panels, and governments with landfills that reclaim methane gas. This open market approach could accelerate profitability and speed further investments in renewable energy generation. Broadcast demand-response alerts to lower peak energy demand and reduce the need for utility companies to start reserve generators. Remote energy-management services and energy-control operations will also advise consumers, giving them the choice to control their homes remotely to reduce energy use. Allow utility companies to increase their focus on Save-a-Watt or Nega-Watt programs instead of producing only power. These programs are effective because offsetting a watt of demand through energy efficiency can be more cost-effective and CO2-efficient than generating an extra watt of electricity.15

11. Ibid. 12. Al Gore, September 2006, http://thinkprogress.org/gore-nyu 13. International Energy Outlook 2008, Energy Information Administration, 2008, http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/ieo/highlights.html 14. Ibid. 15. Jim Rogers, Duke Energy CEO, December 2007. 9

White Paper

Accelerate Adoption of Renewable Electricity Sources

A Smart Grid will encourage home and building owners to invest in high-efficiency, lowemission microgeneration devices to meet their own needs, and to sell excess energy back to utility companies to offset peak demands on the electrical grid. This will reduce the need for new, large-scale power plants. Virtual power plants can also be created that include both distributed power production and energy-efficiency measures. In addition, a Smart Grid will accelerate the introduction of PHEVs to act as temporary electricity storage devices, as well as provide incremental energy generation to offset peak demand on the grid. Intelligence within the Smart Grid will be required to maintain reliability and stability once tens of thousands of microgeneration devices and PHEVs are brought online.

Delay Construction of New Electricity-generation Facilities and Transmission Infrastructure

It is estimated that the cost to renew the worlds aging transmission and distribution grid will exceed $6 trillion over the next 25 years.16 Utility companies that implement electronic monitoring and management technologies can prolong the life of some electrical grid components, thus delaying their replacement. This will reduce new construction and installation costs for the grid and the CO2 emissions that accompany them.

First Steps

Practically speaking, most of the technologies required to create a Smart Grid are available today. In fact, forward-looking utility companies are already using these technologies to deliver solutions to their customers. For example, many utility companies are offering demand-response programs for their corporate customers, and increasingly for residential customers. In addition, some utility companies are implementing large numbers of smart electric meters to offer variable pricing to consumers and to reduce manual meter-reading costs. While these first steps are encouraging, more needs to be done.

Making the Smart Grid a Reality

There is a growing consensus that as governments, regulators, utility companies, and businesses work together, the Smart Grid will become a reality. This section provides ideas and suggestions about how each stakeholder can remove barriers, streamline processes, and institute programs that will speed development of the Smart Grid (see Figure 3).

16. World Energy Outlook, 2006.

10

White Paper

Figure 3. Suggested Actions for Key Stakeholders

Government and Energy Regulators

Provide financial incentives to encourage adoption Improve collaboration and sharing of Smart Grid pilot project results among countries and states Direct more R&D funding and incentives to renewable energy-generation and carbon-sequestration initiatives Provide clear information and incentive programs to consumers to encourage installation of renewable energy generation in their homes Encourage agreement on and adoption of critical technology standards Consider variable, time-based electricity pricing as an alternative to flat-rate pricing Consider policies that set targets for the percentage of electricity coming from renewable energy-generation sources

Electric Utility Companies

Form partnerships to drive Smart Grid standards Become involved before Smart Grid technologies converge and standards are set Plan for the financial impact of the Smart Grid

Technology Companies

Partner to improve systems integration Increase risk-taking to speed development Create new markets to ensure participation and success

Source: Cisco IBSG, 2008

The Role of Government and Energy Regulators

Governments and energy regulators have important roles to play in accelerating development and ensuring success of the Smart Grid. Here are several ways they can participate: 1) Use financial incentives to encourage Smart Grid adoption. Typically, utility companies increase earnings by selling more electricity. This can be a disincentive for utilities to promote energy efficiency. Since 1982, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) has pursued policies that separate utility sales from profits as a means to accelerate energy-efficiency investmentsallowing utility companies to recoup lost profits through minor rate increases. Instead of utility companies passing on the costs of building new plants to meet increased energy demand, consumers avoid the costs of new power plant construction and benefit from decreased energy consumption. This provides an incentive for utility companies to accelerate development of energy-saving solutions that can increase profits, despite reducing overall energy sales. Some states are endorsing Californias approach, including Oregon, Maryland, Idaho, New York, and Minnesota. Other states are concerned that consumers electricity prices will rise excessively and are waiting to ensure that energy savings will more than offset implementation costs before allowing utility companies to increase customer

11

White Paper

tariffs. While the jury is still out, Californias per-capita energy use has remained relatively flat over the last 30 years. By comparison, per-capita energy use in the rest of the country has surged by 50 percent.17 2) Promote better collaboration and sharing of Smart Grid pilot project results among countries and states. In particular, a multinational research oversight organization that carefully measures and communicates costs, benefits, and risks of all Smart Grid pilot projects to utility companies and regulators could accelerate Smart Grid adoption by providing quantitative results about which solutions are most effective. 3) Direct more R&D funding and incentives to renewable energy-generation and carbon-sequestration initiatives. Redirecting limited government funding away from other programs is never easy. A recent Stern Review18 report found, however, that postponing investments to develop greenhouse-gas-reducing technologies is a bad economic decision. Stern estimates that each year-long delay in developing these technologies will result in the need to spend several times that amount in the future. 4) Provide clear information and incentive programs to consumers to encourage installation of renewable energy generation in their homes. Programs could include marketing campaigns to build awareness and generate excitement, calculators to show return on investment (ROI), and economic rebates and low-cost financing to promote purchases of energy-generation equipment. 5) Encourage agreement on and adoption of critical technology standards. The building industry, for example, has been battling over control-system protocols for more than 10 years. This has significantly delayed the introduction of integrated, energy-efficient building solutions. Todays electrical grid has hundreds of different proprietary data protocols that do not easily communicate with each other. 6) Consider variable, time-based electricity pricing as an alternative to flat-rate pricing. This provides a more natural supply-and-demand market, where consumers can choose to use less energy when the price is high, such as during hot summer afternoons. Similarly, variable pricing would allow consumers to see the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from their own electricity use, further encouraging conservation. 7) Consider policies that set targets for the percentage of electricity coming from renewable energy-generation sources. For example, the 2007 U.S. Energy Act initially specified that 15 percent of all U.S. electricity must come from renewable energy by 2020, of which 4 percent could be achieved by energy-efficiency solutions. This requirement was removed from the final legislation. If passed, these types of policies can help accelerate investments in renewable and efficient energy solutions. The cost to implement these requirements, however, is yet to be determined.

17. Californias Decoupling Policy, California Public Utilities Commission, 2008, http://www.cpuc.ca.gov/cleanenergy/design/docs/Deccouplinglowres.pdf 18. Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, 2006.

12

White Paper

Role of Electric Utility Companies

Electric utility companies also play a central role. Here are three ways they can help make the Smart Grid a reality: 1) Drive Smart Grid standards and architectures by forming alliances and partnerships. Many utility companies are now reaching out to other utility companies to learn from their findings and share ideas. In addition, strategic partnerships, both within and outside the utility industry, are being formed. Utility companies should also partner more closely with energy regulators to determine their current position on recapturing costs through tariff increases, while at the same time evaluating how to influence policies to accelerate their own Smart Grid investment plans. 2) Evaluate Smart Grid solutions and vendors. While there is still significant churn in various Smart Grid technologies, waiting a couple years for the Smart Grid industry to converge around a single set of standards and solutions may leave some utility companies behind. 3) Plan for the financial impact of the Smart Grid on their organizations. Utility companies should start by understanding the costs related to developing the Smart Grid, including carbon pricing, grid upgrades, raw energy, and the indirect cost of competition from other utility companies offering energy-efficient services. Once these costs are understood, utility companies should estimate the economic impact Smart Grid solutions could have on their profits. This exercise will help utility companies quantify the effect of the Smart Grid on their bottom line.

Role of Technology Companies

There are three imperatives for technology companies to accelerate development of the Smart Grid: 1) Partner with other technology companies to improve systems integration. rom a technology perspective, building the Smart Grid is relatively easy since most F of the core technologies already exist. The real challenge is integrating the various technologies into a single, working solution. 2) Increase risk-taking. In a recent discussion with technology companies, Jim Rogers, CEO of Duke Energy, said, Because Smart Grid ideas are evolving so quickly, technology companies need to become more comfortable taking risks and applying their technologies to new applications. Rather than wait for the perfect solution or comprehensive standard to be developed, companies need to rapidly get their solutions into the marketplace to be tested and vetted.19

19. Jim Rogers, Duke Energy CEO, December 2007.

13

White Paper

3) Create new markets. Large, successful, and established technology companies often pursue a fast follower strategy, waiting for markets to develop before they participate. This approach is popular because it reduces risks and increases the probability of success. The Smart Grid, however, may evolve in a way that negates the benefits of using a fast-follower strategy. he core technology and communications standards required to develop the Smart T Grid are currently being developed. Once these standards are established, they will be built into the power plants, substations, buildings, and power lines that make up the electrical infrastructure. These assets have a useful life of more than 30 yearsmuch longer than the product lifecycles to which technology companies are accustomed making it difficult to enter the utility marketplace once it is established.

Conclusion

Energy is a critical concern to city leaders. The electricity and fuel used to power our homes and buildings are the leading causes of greenhouse gas emissions by cities. Rising demand for energy may significantly increase consumer costs. Aging grid infrastructure raises the risk of power losses and resulting economic shortfalls. Rising fuel costs, underinvestment in an aging infrastructure, and climate change are all converging to create a turbulent period for the electrical power-generation industry. To make matters worse, demand for electricity is forecast to exceed known committed generation capacity in many areas across the United States.20 And, as utility companies prepare to meet growing demand, greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation may soon surpass those from all other energy sources.21 Fortunately, the creation of a Smart Grid will help solve these challenges. A Smart Grid can reduce the amount of electricity consumed by homes and buildings, and accelerate the adoption of distributed, renewable energy sourcesall while improving the reliability, security, and useful life of electrical infrastructure. Despite its promise and the availability of most of the core technologies needed to develop the Smart Grid, implementation has been slow. To accelerate development, city, state, and federal governments, electric utility companies, public electricity regulators, and IT companies must all come together and work toward a common goal. The suggestions in this paper will help the Smart Grid become a reality that will ensure we have enough power to meet demand, while at the same time reducing greenhouse gases that cause global warming.

20. Long-Term Reliability Assessment 20072016, North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), October 2007. 21. Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, 2006.

RM/LW15156 1008

14

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Philips XOP-15 - DatasheetDocument3 pagesPhilips XOP-15 - DatasheetGiovani AkNo ratings yet

- Electromagnetic Relays - ManiDocument17 pagesElectromagnetic Relays - ManipraveenaprabhuNo ratings yet

- Project SynopsisDocument8 pagesProject Synopsistaran jot100% (1)

- Philips Saeco Intelia hd8752 SM PDFDocument61 pagesPhilips Saeco Intelia hd8752 SM PDFAsad OnekNo ratings yet

- CT Saturation and Its Influence On Protective Relays: Roberto Cimadevilla, Ainhoa FernándezDocument22 pagesCT Saturation and Its Influence On Protective Relays: Roberto Cimadevilla, Ainhoa FernándezANTONIO SOLISNo ratings yet

- Bhagvender Singh XII-A Physics Project PDFDocument15 pagesBhagvender Singh XII-A Physics Project PDFvoid50% (4)

- Arlan Alvar: Compex Certified E&I Ex Inspector (Qa/Qc) Available For New OpportunityDocument3 pagesArlan Alvar: Compex Certified E&I Ex Inspector (Qa/Qc) Available For New OpportunityDo naNo ratings yet

- Electric Vehicle ChargingDocument60 pagesElectric Vehicle Chargingvinod 7100% (1)

- General CatalogueDocument26 pagesGeneral CatalogueKasturi LetchumananNo ratings yet

- Nerc Sra 2022Document46 pagesNerc Sra 2022The Western Journal100% (1)

- BMU Titan Cradle: Standard Features Control BoxDocument2 pagesBMU Titan Cradle: Standard Features Control BoxKashyapNo ratings yet

- Simon Dagher ProjectDocument114 pagesSimon Dagher ProjectSimon DagherNo ratings yet

- Ncpfirst - X-Form - PDF Example: (Epc - Dedicated Front Cover Sheet Here)Document12 pagesNcpfirst - X-Form - PDF Example: (Epc - Dedicated Front Cover Sheet Here)Anil100% (1)

- Steam Turbines Basic Information - Power Generation in PakistanDocument12 pagesSteam Turbines Basic Information - Power Generation in Pakistannomi607No ratings yet

- Niven, Larry - at The Bottom of A HoleDocument10 pagesNiven, Larry - at The Bottom of A Holehilly8No ratings yet

- Unit 4: Fault Analysis EssentialsDocument9 pagesUnit 4: Fault Analysis EssentialsBALAKRISHNAN100% (2)

- Ingersoll Rand VR-843CDocument2 pagesIngersoll Rand VR-843CMontSB100% (1)

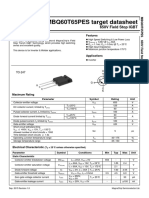

- MBQ60T65PES Target Datasheet: 650V Field Stop IGBTDocument1 pageMBQ60T65PES Target Datasheet: 650V Field Stop IGBTamrNo ratings yet

- Flow of Lubricating Greases in Centralized Lubricating SystemsDocument8 pagesFlow of Lubricating Greases in Centralized Lubricating SystemsFelipe LeiteNo ratings yet

- Photoassociation Spectroscopy of A Spin-1 Bose-Einstein CondensateDocument5 pagesPhotoassociation Spectroscopy of A Spin-1 Bose-Einstein Condensatee99930No ratings yet

- Topic 2.4 - Momentum and ImpulseDocument38 pagesTopic 2.4 - Momentum and ImpulseKhánh NguyễnNo ratings yet

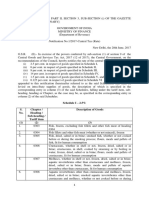

- Notification 1 2017 For CGST Rate ScheduleDocument74 pagesNotification 1 2017 For CGST Rate ScheduleIti CglNo ratings yet

- Fermentor TypesDocument33 pagesFermentor TypesFahad MukhtarNo ratings yet

- Back To Basics - RTO MediaDocument2 pagesBack To Basics - RTO Mediaguardsman3No ratings yet

- Lime Calcination: Gupta Sudhir Kumar, Anushuya Ramakrishnan, and Yung-Tse HungDocument2 pagesLime Calcination: Gupta Sudhir Kumar, Anushuya Ramakrishnan, and Yung-Tse HungSaurabh NayakNo ratings yet

- High Voltage Engineering Ref ManualDocument147 pagesHigh Voltage Engineering Ref Manualzeus009100% (1)

- Abiogenesis PDFDocument16 pagesAbiogenesis PDFErik_Daniel_MajcherNo ratings yet

- SK200-8 YN11 Error CodesDocument58 pagesSK200-8 YN11 Error Codest544207189% (37)

- Thermal Protector For Motor: Ballast For Fluorescent and Temperature Sensing ControlsDocument1 pageThermal Protector For Motor: Ballast For Fluorescent and Temperature Sensing ControlsPasilius OktavianusNo ratings yet

- SKF TIH 030M - 230V SpecificationDocument3 pagesSKF TIH 030M - 230V SpecificationÇAĞATAY ÇALIŞKANNo ratings yet