Professional Documents

Culture Documents

00039

Uploaded by

Gabrielle Migner-LaurinOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

00039

Uploaded by

Gabrielle Migner-LaurinCopyright:

Available Formats

Editorials

Poor survival after cardiac arrest resuscitation: A self-fullling prophecy or biologic destiny?*

ignicant progress has been made in resuscitation science, with better chest compression, use of automated debrillators (1, 2), and in postresuscitation care with therapeutic hypothermia and comprehensive critical care (3, 4). Disappointingly, however, the overall survival to discharge remains dismally low at 9.6% for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and 17% for in-hospital arrest (57). As we try to look for opportunities to further improve outcomes of patients at the bedside, study cohorts in clinical trials, and the population in general, one area that has escaped a focused approach is end-of-life decisions in the intensive care unit. These practices cover issues relating to the dying patient and include the limitation of care with do-not-attempt resuscitation status and the enactment of withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies. Implicit in the care of these critically ill patients is the matter of neurologic assessment, both with regard to concurrent validity and to prognosis, that has a direct impact on treatment decisions and outcome (8). In this issue of Critical Care Medicine, Perman and colleagues (9) bring forward some important and controversial issues on end-of-life care in critical care in a retrospective study of 55 consecutive patients treated with hypothermia after cardiac arrest resuscitation. Looking at the timing when prognosis was assigned, the authors found that 57% (28 of 55) of their cohort were given a poor or grave prognosis while they were still actively being cooled, or within 15 hrs after hypothermia when they were rewarmed. The early

*See also p. 719. Key Words: cardiac arrest; cardiopulmonary resuscitation; hypothermia; mortality; outcome; prognosis; withdrawal of life support Dr. Geocadin is supported, in part, by an NIH grant (R01-HC071568). Drs. Peberdy and Lazar have not disclosed any potential conicts of interest. Copyright 2012 by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182410146

poor prognosis was assigned by the primary medical service in 75% and by a neurology consultant in 25% of cases. Of these 28 patients, 18 (64%) were assigned poor prognosis at the time that they were receiving sedating and paralytic drugs, and actively under hypothermia therapy. Subsequently, eight survived and 20 died. Of the eight survivors, six had good outcomes (cerebral performance category 1 or 2) and two had poor outcome (cerebral performance category 3 or 4), demonstrating weak predictive validity of the early poor prognosis. A rich literature on prognostication for neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest has led to new consensus statements (5, 10) and updated practice parameters (11). Of all the factors studied, it has been established that neurologic status, as reected by the bedside neurologic examination and neurologic-based testing after resuscitation, is the most reliable predictor of functional outcome. As pointed out by Perman et al (9), however, these neuro-based prognostic paradigms have been not been thoroughly validated in patients treated with hypothermia. The cornerstone of central nervous system evaluation continues to be a wellexecuted neurologic examination and testing (11, 12). It is critical, however, that assessment be undertaken in conditions that reect the true neurologic status of the patient. Any factor outside of the primary hypoxic-ischemic injury that will confound neurologic assessment has to be corrected and assessment delayed until the mitigation of such factors. Of particular relevance to Perman et al, the assignment of poor prognosis while the patient is still actively being treated with hypothermia and receiving sedatives and paralytics is troublesome. Hypothermia as well as ischemic injury to liver and kidneys is known to alter the metabolism and delay clearance of these medications. Under these conditions, neurologic function will likely be grossly underestimated, leading to the misleading conclusion of greater neurologic injury and mis-

assignment of prognosis. Because several major professional guidelines have warned against prognostication under these circumstances, this paper raises important concerns. Furthermore, we nd the assignment of poor prognosis even more troublesome because the clinical features used for prognosis were not documented. The importance of timing of neurologic assessment during prognostication is related to the earliest period in which brain structures can recover function to allow reliable clinical testing; prognostication too soon will miss the recovery process and mistakenly assume more permanent neurologic injury. In postcardiac arrest patients who have not been subjected to therapeutic hypothermia, the timing for most reliable assessments starts at 72 hrs after the resuscitation (5, 10, 11). But in those treated with therapeutic hypothermia, the period of observation needs to be at least the same and likely even longer. Therapeutic hypothermia has been demonstrated to improve both survival and quality of life of survivors (35, 10). With our understanding of the impact of therapeutic hypothermia on neurologic recovery and prognostication still evolving, it is imperative that we allow some time for patients to recover. The premature assignment of poor prognosis is worrisome, but even more concerning is the fact that this was undertaken by both medical specialists and neurologists. In this patient population, the assignment of poor prognosis typically results in reduction in the level of care or withdrawal of care leading to death (8). Peberdy et al (6) reported a 66% overall mortality in 14,720 patients who were resuscitated from in-hospital cardiac arrest. Of those who died, 63% were declared do-not-attempt resuscitation after resuscitation, and 43% of those who died had life support withdrawn. It is unclear how the decision of do-not-attempt resuscitation or withdrawal of care was reached, but if we consider the conditions in the Perman study, where premature

979

Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 40, No. 3

assignment of poor prognosis altered care leading to poor outcomes, the selffullling prophecy is notable. Survival from cardiac arrest will never improve so long as we are giving up on potentially salvageable patients. The impact goes beyond individual survival. How then do we determine efcacy in a clinical trial when mortality may be governed not by disease and treatment, but by withdrawal of care? We are left to infer that premature prognostication and faulty end-of-life decisions have likely biased results of treatment trials toward failure. While this paper provides a springboard for discussion on prognosis, we have to acknowledge its limitations, including: 1) retrospective design, 2) lack of justication for the prognosis assigned from the medical chart, 3) lack of documentation of family and treating team interactions, and 4) the small sample that prevents drawing generalizable conclusions. Despite these limitations, however, it provides us an opportunity to reect on how neurologic assessment is undertaken, how neurologic prognostication can impact mortality at the bedside, and possibly how it can affect the way we undertake clinical trials. We do recognize the need to limit care at some point, especially with worsening morbidity, cost of prolonged futile care, and the moral need to respect patient preferences in light of severe incapacitation. Determining prognosis in critically ill patients remains one of the most important and difcult tasks for physicians in the intensive care unit (13). But it is only when prognostication is undertaken with the most valid, available evidence can we provide the best care that will not only benet our individual patients, but also help move the science forward. It is time that we focus on end-of-life practices to better understand the role that self-fullling prophecy or biological des-

tiny play in patients with poor outcome after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Romergryko G. Geocadin, MD Departments of Neurology, Anesthesiology-Critical Care Medicine, and Neurosurgery Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Baltimore, MD Mary Ann Peberdy, MD Department of Internal Medicine (Cardiology) Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine Richmond, VA Ronald M. Lazar, PhD Department of Neurology Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons New York, NY

6.

7.

REFERENCES

1. Weisfeldt ML, Sitlani CM, Ornato JP, et al: Survival after application of automatic external debrillators before arrival of the emergency medical system: Evaluation in the resuscitation outcomes consortium population of 21 million. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55: 17131720 2. Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, et al: Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2010; 304:14471454 3. Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al: Treatment of comatose survivors of out-ofhospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:557563 4. Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group: Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:549 556 5. Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, et al: Postcardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation 2008; 118: 24522483 Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: A report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2003; 58: 297308 McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, et al: Out-ofhospital cardiac arrest surveillance Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005December 31, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011; 60:119 Geocadin RG, Buitrago MM, Torbey MT, et al: Neurologic prognosis and withdrawal of life support after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Neurology 2006; 67:105108 Perman SM, Kirkpatrick JN, Reitsma AM, et al: Timing of neuroprognostication in postcardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:719 724 Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW, et al: Part 9: Post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010; 122: S768 S786 Wijdicks EF, Hijdra A, Young GB, et al: Practice parameter: Prediction of outcome in comatose survivors after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2006; 67:203210 Xiong W, Hoesch RE, Geocadin RG: Postcardiac arrest encephalopathy. Semin Neurol 2011; 31:216 225 Bernat JL: Ethical aspects of determining and communicating prognosis in critical care. Neurocrit Care 2004; 1:107117

980

Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 40, No. 3

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Your Guide To Putting A Heart Safe Aed Program in PlaceDocument15 pagesYour Guide To Putting A Heart Safe Aed Program in PlaceDan ZoltnerNo ratings yet

- Chinese Journal of Traumatology: Geley Ete, Gaurav Chaturvedi, Elvino Barreto, Kingsly Paul MDocument4 pagesChinese Journal of Traumatology: Geley Ete, Gaurav Chaturvedi, Elvino Barreto, Kingsly Paul MZilga ReginaNo ratings yet

- ATLS NotesDocument22 pagesATLS NotesJP93% (15)

- First Aid: Immediate and Temporary Care Given byDocument18 pagesFirst Aid: Immediate and Temporary Care Given byJd Jamolod PelovelloNo ratings yet

- Evolve Resources For Medical Surgical Nursing 7th Edition Lewis Test BankDocument8 pagesEvolve Resources For Medical Surgical Nursing 7th Edition Lewis Test Bankhungden8pne100% (29)

- Chain of Survival: Adult and Pediatric Out of Hospital Cardiac ArrestDocument10 pagesChain of Survival: Adult and Pediatric Out of Hospital Cardiac ArrestJapeth John M. FloresNo ratings yet

- Bitumen Safety CodeDocument69 pagesBitumen Safety CodeVictor Eugen100% (2)

- Delivery Room: History Back To TopDocument4 pagesDelivery Room: History Back To TopeskempertusNo ratings yet

- MFHF Instruction Manual PDFDocument220 pagesMFHF Instruction Manual PDFTanvir ShovonNo ratings yet

- CPR Demonstration: Students Learn Life-Saving ProcedureDocument24 pagesCPR Demonstration: Students Learn Life-Saving ProcedureSamiksha Magendra100% (1)

- Code Blue Policy - Adult Care Sites - Calgary ZoneDocument9 pagesCode Blue Policy - Adult Care Sites - Calgary ZoneLLyreONo ratings yet

- ACLS Test BankDocument13 pagesACLS Test BankSofiaSheikh94% (51)

- Advanced Cardiac Life Support (Acls) Part I: ACP 202 Module 6Document32 pagesAdvanced Cardiac Life Support (Acls) Part I: ACP 202 Module 6MoeNo ratings yet

- Emrgency Guidelines 3 RD EditionDocument123 pagesEmrgency Guidelines 3 RD EditionMitz MagtotoNo ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDocument21 pagesCardiopulmonary ResuscitationVesnickNo ratings yet

- Emergency Guidelines for Medical EmergenciesDocument72 pagesEmergency Guidelines for Medical EmergenciesRumana Ali100% (2)

- DFU SimMan 3G Trauma RevADocument64 pagesDFU SimMan 3G Trauma RevAForum PompieriiNo ratings yet

- Gender Equality and Development in the PhilippinesDocument82 pagesGender Equality and Development in the PhilippinesKim NaheeNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Army Disaster Management TrainingDocument6 pagesBangladesh Army Disaster Management TrainingMuhaimin AkibNo ratings yet

- Riggs 2019Document14 pagesRiggs 2019navenNo ratings yet

- ACLSDocument39 pagesACLSJason LiandoNo ratings yet

- CPR MCQ 04Document46 pagesCPR MCQ 04Ryam Taif100% (1)

- CPR InfantDocument35 pagesCPR InfantHamil BanagNo ratings yet

- jma3910 25安装使用手册Document256 pagesjma3910 25安装使用手册bg2ttNo ratings yet

- Trauma and Emergency NursingDocument9 pagesTrauma and Emergency Nursingchinthaka18389021No ratings yet

- In Hospital Cardiac ArrestDocument3 pagesIn Hospital Cardiac ArrestsaltarisNo ratings yet

- Neopuff rd900 PiskhtcDocument4 pagesNeopuff rd900 PiskhtcDuit LanangNo ratings yet

- Emergency Trauma EMQ-32: Head Injury Management and Shock TypesDocument34 pagesEmergency Trauma EMQ-32: Head Injury Management and Shock TypesassssadfNo ratings yet

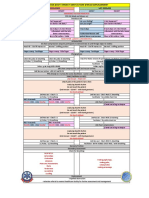

- BLS ALGORITHM As of February 2023Document2 pagesBLS ALGORITHM As of February 2023Mark Jason Rodriguez, RNNo ratings yet

- Handout On First Aid, Rescue & Water Safety: Dr. Jezreel B. VicenteDocument39 pagesHandout On First Aid, Rescue & Water Safety: Dr. Jezreel B. Vicentewy100% (2)