Professional Documents

Culture Documents

James Hillman The Gods and Soul David Miller

Uploaded by

Farshad FouladiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

James Hillman The Gods and Soul David Miller

Uploaded by

Farshad FouladiCopyright:

Available Formats

American Academy of Religion

Review: The Gods and Soul: An Essay-R eview Auth or(s): David L. M iller So urce: Journ al of the A m erican A cad e m y o f R eligion, Vol. 43, No. 3 (Sep., 1975), pp. 586-590 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1461854 Accessed: 16/10 /2011 12 :35

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press and American Academy of Religion are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Academy of Religion.

http://www.jstor.org

The Gods and Soul: An Essay-Review*

D AV ID L.M ILLER

N iconoclastic prophetism and a metaphoric reformation in the published version of James Hillman's 1972 Terry Lectures at Yale University make crucial for the study of Religion and at the same Re- Visioning Psychology time difficult to review. How is one to review a re-view, catching Hillman's own episodic argument by its aphoristic tail while hunter and quarry are both running in circles? I t is like trying to see the eye with which one is seeing. Viconian cyclometry is never easy, but perhaps important. Hillman's imaginal way of re-viewing psychology is seen in his master tropes. Personifying is the re-peopling of the universe of meaning, seeing images in ideas, and bringing thought to life by seeing life in thought. "Words are persons," Hillman notes with the poet, and he adds a psychologist's conclusion: "Personifying is the soul's answer to egocentricity." Pathologizing is discovering a mythology in symptoms, finding stories in hurts, transforming messes into variegated richness. This is perhaps most crucial of all the tropes, and it leads Hillman to say: "By clinging faithfully to the pathological perspective which is the differential root of its discipline, distinguishing it from all others, depth psychology maintains its integrity, becoming neither humanistic education, spiritual guidance, social activity, nor secular religion." Psychologizing (precisely the opposite of psychologism) is seeing through the literalism of every positivism, metamorphosizing through metaphor, forsaking both letter and spirit for soul. Hillman sees literalism psychologically as an ego viewpoint and suggests the strategy of metaphor (performing one activity as if it were another) as peculiarly felicitous for "soul-making" (his phrase for psychologizing). Hillman wants to 'join Owen Barfield and Norman Brown in a mafia of the metaphor to protect plain men from literalism" - and from the egoism of one-dimensional selfunderstanding. This leads Hillman to his fourth trope, dehumanizing, which is understood as the release of the personal into deeper soul power, a transcendence of epic voluntarism of ego into the mythological many-faceted nature of the archetypal self (not just Oedipus, but all the presiding metaphors of all the complexes). Since "humanism's psychology is the myth of man without myths," archetypal psychology means dehumanizing, archetypologizing, re-

Re- Visioning Psychology. By JAMES HILLMAN. New York: Ha rper & Row, 1975. xvii+266 pages. $12.50. L.C. No. 74-25691.

DA JJJ L. MILLER, Professor of Religion at Syracuse University, is presently in France writing. He IS the a uthor of Gods and Games and The New Polytheism.

586

THE GODS AND SOUL

587

mythologizing, and theologizing. "A re-vision of psychology," says Hillman, "means recognizing that psychology does not take place without religion, because there is always a God in what we are doing." Just the same, Hillman wishes neither to psychologize religion nor to redeem it: "Archetypal psychology's concern is not with the revival of religion, but with the survival of soul." A glance at the topography of Hillman's argument will begin to demonstrate how the gods and soul-power connect.

TOPOGRAPHY

1. Psychology. Hillman is to Jungian psychology as Norman 0 . Brown is to Freudian and as Ronald D. Laing is to Existentialist. Formally speaking, though they disagree strongly in content, they are all radical revisionists. Hillman's new work makes this observation particularly compelling when seen in relation to his earlier writings. Re- Visioning Psychology stands in reference to the rest of the corpus (principally The Myth of Analysis; Insearch; Suicide and the Soul; Emotion; and the essays on Pan, Kundalini, Feeling, Anima, and the Child) as Brown's Love's Body and Laing's Knots are to their earlier works (principally Life Against Death and The Divided Self, respectively). Language in the later works of each man explodes. The text approaches poetry, stopping just short of lyric in aphorism. The "argument," if such a term is proper to the mode of thinking in Knots, Love's Body, and Re- Visioning Psychology, is "episodic and circular." A prose organization of Hillman's book may fool the reader into not noticing that actually the work has no rigid beginning or ending, a characteristic that the author has himself acknowledged. As Brown's, Laing's, and Hillman's books "end," the texts turn back upon themselves, like literate Moebius strips, and what may have seemed to have been statements in an argument turn into self-implicating insights. The whole vanishes, leaving the reader with nothing to see, but with something much more valuable: a way of seeing. So Hillman can write:

The psychological mirror that walks down the road, the Knight Errant on his adventure, the scrounging rogue, is also an odd-job man, like Eros the Carpenter who joins this bit with that, a handyman, a bricoleur - like "a ball rebounding, a dog straying or a horse swerving from its direct course" - psychologizing upon and about what is at hand; not a systems-architect, a planner with directions. And leaving, before completion, suggestion hanging in the air, an indirection, an open phrase. . . . (p. 164)

2. Philosophy. Such errancy talk as this and the observation of a formal relation between Hillman's book and the latter-day thinking of Brown and Laing brings to mind Wittgenstein and Heidegger. Like the works of these men, ReVisioning Psychology goes beyond traditional metaphysics, at least beyond a psychology which is trapped by Cartesian rationalism and Aristotelian substantialism in ideas about the self. The transcendent leap-frogging appears, not in the weighty manner of Heidegger in Being and Time, nor in the gamey manner of Wittgenstein in the Tractatus; rather, Re- Visioning Psychology is more like the later philosophical writings of Heidegger and Wittgenstein. Hillman's new book stands in relation to his previous work exactly as Heidegger's Gelassenheit and the essays on poetry are to Being and Time, and as Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations are to the Tractatus and the later essays. The Hillmanian breakthrough from rationalism and substantialism is also indicated,

588

DAVID L. MILLER

philosophically, by his move behind Descartes and Aristotle to Plato and Heraclitus. Hillman is clearly a self-conscious friend of the Renaissance neoplatonists, which leads to a third way of placing his work. 3. Letters. In the realm of ideas Hillman's soul-mates are Gnosticism, Alchemy, and Romanticism (especially William Blake). Yet all traces of relativism, subjectivism, and psychologism are gone. They are precisely the enemy, for they represent the ego turned inward upon its epic, voluntaristic, rational, and heroic self. Hillman's viewing is archetypal and collective. However, it is not collective in the sociological sense, but in some vertical resonance that becomes trans-personal (he notes that in the term bathos, as used by Heraclitus, depth was not distinguished from height). Psyche (soul) is not in the personal self (ego), but the self is in objective soul. Mythology is the universal location where soul makes itself manifest in some non-relativistic and non-solipsistic sense. This places Hillman's work also in relation to Picasso and Joyce for whom mythology was so important. Indeed, like Freud's work which, as Hillman notes, won the Goethe prize for literature rather than the Nobel Prize for medicine, Re- Visioning Psychology fits most appropriately in the realm of imaginal psychology. Its creativity is manifest in the "heIter skelter"form of the book. Digressions interrupt the sequences in the text by coming out of the blue. Thematic materials are often expressed paradoxically and seldom move develop_ Jentally. But the creativity is also found in the substance of the work's metaphoric imagery. This occurs however not without tough-headed and iconoclastic thinking. 4. Theology. Iconoclasm suggests prophetism and protestantism. To say that Hillman's work is protestant will be offensive to its author. He spends much space in the final sections of the book bemoaning the Germanic, Protestant tone of contemporary psychology with its "literalism and voluntarism." He says: "It does not matter whether we are behaviorists or strict Freudians, whether we are engaged in self-mastery or self-surrender, introspection or statistics, or whether we try to break loose with glossolalia, creative painting, and nude encounters, psychology remains true to its Reformational background" (p. 220). That Hillman feels negatively about such Reformation psychology becomes clear when he remarks that all that is accomplished by it is that "the weight and seriousness of psychotherapy (even in the California suqshine schools) create in its participants new loads of guilt, now in regard to the morality of its therapeutic aims" (p. 221 ). Yet in spite of Hillman's anti-Protestant talk, nay, precisely because of his protestant iconoclasm against Protestantism, Re- Visioning Psychology is protestant. It is not this in the socio-historical sense that the author is seeing the Protestant Reformation, but rather in Paul Tillich's theo-philosophical sense of "the protestant principle," where there abound categories of the autonomy of grace and sin, the priesthood of all believers, and the bondage of the heroic will of spirit in matters of ultimate meaning. All these notions, and especially that of priesthood of all believers, implicate the "protestant principle" in an unconscious conspiracy with Hillman in the direction of incipient polytheism, a function that shows itself in the many denominations and sects that have flourished within the "protestant" framework. Hillman locates himself in this symbolic and metaphoric protestantizing, but not with northern European churchism, when he writes on "The Empire of the Roman Ego: Decline and Falling Apart." In this section he is careful to note the close connection between Roman imperialism in religion and society, on the one

THE GODS AND SOUL

589

hand, and the psychological fantasy of heroic egoism, on the other. Hillman says: "If it is common today to fantasy our culture against that of old Rome, it is partly because our psyche has undergone a long Pax Romana." But now "central command is losing control" (p. 26). Theologically this puts Re- Visioning Psychology near Luther and opposed to popery, but of course also in direct opposition to sixteenth-century Protestant scholasticism and Pharisaism. Ex UNo

PLURES

In all of this Hillman has associated himself with a number of writers who have argued, not only for radical pluralism in self and society, but for cosmic and ontic polytheism. Vincent Vycinas' Search for Gods (Nijhoff, 1972), the new translation of Alain's Les Dieux (New Directions, 1974), and E. M. Cioran's The New Gods (Quadrangle, 1974) are just a few examples. For Vycinas the philosophical task is to search for the gods during the twilight of the gods because the gods "carry the meanings and the realness of things." For Alain, "the gods are everywhere . . . Where there is only a man, there is a god." And to Cioran, "monotheism contains the germ of every form of tyranny." The question in these theorizings, as in that of Hillman, is why in the plursignification of meaning, in the radical or ethnic pluralism of society, in the polyvalence of the self, in the general attack on onedimensional meaning- and symbol-systems - w h y in all of these is there required the additional step to polytheism, to the gods? Are the gods of polytheism any less dead or eclipsed than the God of monotheism? Perhaps it was Sigmund Freud who began to make inroads on this question. When single-minded religious meaning - the moralistic and doctrinal meaning of Torah and Creed - fa il e d in the lives of individuals, two things were noted: (1) the meaning was likely projected in the first place out of a memory and out of a personal need for completion, and (2) the full experience of the lack (the death of God) could not be therapeutically fruitful until the personal narrative and need were broken through by a transpersonal context (e.g., Oedipus). Carl Jung's experience was similar, but even more radical. Freud had noted many complexes, each with a single archaic structure (not only Oedipus, but Eros and Thanatos and so on). For Jung each complex has more than one archetype: the anima-complex may be informed by Artemis, Helen, Psyche, Electra, Eileithyia, Kastalia, and I or many others. It is Hillman, however, who shows why the recovery of soul power is ineluctably tied in his own work, as in that of Freud and Jung, to gods - precisely at the moment of God's being called into question as a source of deep meaning. Hillman's argument and his method is one of "reversion," and it is based on a view of memoria that is found first in St. Augustine. Hillman discovers in personal moods a number of fantasies. Within each fantasy (a narrative structure imagined in biographical memoria) there is a complex. Within each complex there are, in the manner of Jung, many archetypes. Each archetype has its articulation in a myth. And a god or goddess presides over each myth. "Reversion" is not a new mode of diagnosis; it is rather a way - a way to get purchase on one's own experience of the events of life. I t makes events eventful. In the stories of universal memory chronos becomes kairos. What otherwise may be causal and logical is now experienced synchronistically as a narrative sequence, a plot. Ideas and thoughts become images and persons. It is not that we must find some gods when God succumbs in culture or lifeexperience. I t is that the gods are there already, released by the death of

590

DAVID L. MILLER

monotheistic thinking whose imperialism caused us to think that the pandaemonium and the polytheism had left. When the bottom drops out of social and personal meaning, the suffering of pathology reveals the manyness of extremity precisely in the form of the personae of the gods and goddesses. This should come as no surprise. Already Aristotle had said in the Metaphysics that all of Homer's pantheon were resident in his ideas. And Wittgenstein, at the other end of our tradition of thinking, told us that pictures were trapped in the syntax of our abstract language. Francis Cornford, in making the connection between Aristotle and Wittgenstein, revealed the pictures to be mythologia. The point is that a viable transcendental referent functions like a lowest common denominator for referential meaning in discourse. I t is crucial to univocal meaning. But if no god-term or god-term-function operates in language or in life, all meanings are loosed at once. God dies and the gods are loosed - and in the Western grammar of meaning this means the Greek pantheon out of whose mythological parataxes, as Aristotle knew, our philosophical and theological syntactical forms were given subjective and predicative shape. Wittgenstein's fly-bottle is filled with Furies (cf. Sartre). The trick is to know how, like Athena in the Oresteia, to take advantage of the poetic power of syntax precisely in its failure, transforming confusion into the multivalent meaning of poesy. Hillman seems to know Athena's trick. I t has to do with personifying, psychologizing, pathologizing, and dehumanizing. That is, it has to do with noticing that the relation between the power of soul-making and the gods is metaphor: the deliteralizing of thinking involves one necessarily in a remythologizing of life. American theology almost got this point in the postBultmannian hermeneutical discussions. What was missing there was not spirit but soul. I t will yet take an appropriation in religious studies of a psychology of religion like Hillman's in order that the full power of metaphor may be felt in the thinking of soul (psychology) and in the thinking about religion (theology). The question is not whether there are gods and goddesses. The question is whether they shall be a resource or an inundating and undifferentiated confusion, a Babel without names. This latter is fragmentation, but fragmentation's articulate name is polytheism.

You might also like

- بنگ ، بکت (1) - Ping, Beckett, SamuelDocument4 pagesبنگ ، بکت (1) - Ping, Beckett, SamuelFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

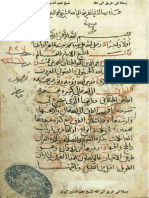

- Risala nAJM kUBRA ANTI MYTHIC NUQTIYYE PDFDocument10 pagesRisala nAJM kUBRA ANTI MYTHIC NUQTIYYE PDFFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Bahaullah The Hidden Words 2002 PDFDocument108 pagesBahaullah The Hidden Words 2002 PDFDubravko AladicNo ratings yet

- مرگ دیگر. بورخس - Another Death, George Luis Borges storyDocument8 pagesمرگ دیگر. بورخس - Another Death, George Luis Borges storyFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Bakhshi Az Nakhostin Fasle Ketabe Baham Sadeghi by M.nikbakhtDocument5 pagesBakhshi Az Nakhostin Fasle Ketabe Baham Sadeghi by M.nikbakhtFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Cannibalism - (In Safavid Dynasty, Part of Iran's History With Analysis)Document23 pagesCannibalism - (In Safavid Dynasty, Part of Iran's History With Analysis)Farshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Gennady Aygi (The POET WHO Is COMPARED To CELAN) - English Translation - Some PoemsDocument19 pagesGennady Aygi (The POET WHO Is COMPARED To CELAN) - English Translation - Some PoemsFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Adonis, Selected PoemsDocument433 pagesAdonis, Selected PoemsPalino Tedoli100% (12)

- Pezeshk e Dehkade Farsi Franz Kafka (Haddad Translation)Document7 pagesPezeshk e Dehkade Farsi Franz Kafka (Haddad Translation)Farshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Vakavi Va Naghd e She'r e Daddy Az Sylvia Plath - Harold BloomDocument22 pagesVakavi Va Naghd e She'r e Daddy Az Sylvia Plath - Harold BloomFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Shrhi Bar Sakhtar e Dastane Ba Kamale.. M.nikbakhtDocument9 pagesShrhi Bar Sakhtar e Dastane Ba Kamale.. M.nikbakhtFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Sfi Spring2011Document2 pagesSfi Spring2011Farshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- E. E. CummingsDocument111 pagesE. E. CummingsElena Ciurea100% (5)

- Atf Al Alif Al Maluf Ala Al Lam Al Matuf Abi Hasan Ali Ibn Muhammad Al Daylami - Aldaylami (Early Pre Ruzbihanian Islamic Philosophy Treatise On Love Pre Ruzbihanian)Document392 pagesAtf Al Alif Al Maluf Ala Al Lam Al Matuf Abi Hasan Ali Ibn Muhammad Al Daylami - Aldaylami (Early Pre Ruzbihanian Islamic Philosophy Treatise On Love Pre Ruzbihanian)Farshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Octavio Paz Piedra Del SolDocument15 pagesOctavio Paz Piedra Del SolNicole Vitalariu100% (2)

- Al GhazaliDocument25 pagesAl GhazaliFarshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- BIS Standards in Food SectorDocument65 pagesBIS Standards in Food SectorRino John Ebenazer100% (1)

- Managing Remuneration MCQDocument5 pagesManaging Remuneration MCQlol100% (1)

- IkannnDocument7 pagesIkannnarya saNo ratings yet

- TypeDocument20 pagesTypeakshayNo ratings yet

- Homologation Form Number 5714 Group 1Document28 pagesHomologation Form Number 5714 Group 1ImadNo ratings yet

- KAMAGONGDocument2 pagesKAMAGONGjeric plumosNo ratings yet

- Spouses vs. Dev't Corp - Interest Rate on Promissory NotesDocument2 pagesSpouses vs. Dev't Corp - Interest Rate on Promissory NotesReinQZNo ratings yet

- Doulci Activator For IOS 9Document2 pagesDoulci Activator For IOS 9Syafiq Aiman100% (2)

- CSEC English SBA GuideDocument5 pagesCSEC English SBA GuideElijah Kevy DavidNo ratings yet

- Symphonological Bioethical Theory: Gladys L. Husted and James H. HustedDocument13 pagesSymphonological Bioethical Theory: Gladys L. Husted and James H. HustedYuvi Rociandel Luardo100% (1)

- Dti Fbgas Conso 2017Document3 pagesDti Fbgas Conso 2017Hoven MacasinagNo ratings yet

- Easy Gluten Free RecipesDocument90 pagesEasy Gluten Free RecipesBrandon Schmid100% (1)

- Present Tense Exercises. Polish A1Document6 pagesPresent Tense Exercises. Polish A1Pilar Moreno DíezNo ratings yet

- Lantern October 2012Document36 pagesLantern October 2012Jovel JosephNo ratings yet

- Chippernac: Vacuum Snout Attachment (Part Number 1901113)Document2 pagesChippernac: Vacuum Snout Attachment (Part Number 1901113)GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Sequence PakistanDocument16 pagesChapter 6 Sequence PakistanAsif Ullah0% (1)

- Public Relations & Communication Theory. J.C. Skinner-1Document195 pagesPublic Relations & Communication Theory. J.C. Skinner-1Μάτζικα ντε Σπελ50% (2)

- Vmware Vsphere Professional 8 Exam Dumps PDF (VCP DCV)Document158 pagesVmware Vsphere Professional 8 Exam Dumps PDF (VCP DCV)romal ghulamNo ratings yet

- Evirtualguru Computerscience 43 PDFDocument8 pagesEvirtualguru Computerscience 43 PDFJAGANNATH THAWAITNo ratings yet

- SalutogenicshandbookDocument16 pagesSalutogenicshandbookAna EclipseNo ratings yet

- MCQ CH 5-Electricity and Magnetism SL Level: (30 Marks)Document11 pagesMCQ CH 5-Electricity and Magnetism SL Level: (30 Marks)Hiya ShahNo ratings yet

- Dell Market ResearchDocument27 pagesDell Market ResearchNaved Deshmukh0% (1)

- Practise Active and Passive Voice History of Central Europe: I Lead-InDocument4 pagesPractise Active and Passive Voice History of Central Europe: I Lead-InCorina LuchianaNo ratings yet

- Public Policy For Nigerian EnviromentDocument11 pagesPublic Policy For Nigerian EnviromentAbishai Auta GaiyaNo ratings yet

- A Random-Walk-Down-Wall-Street-Malkiel-En-2834 PDFDocument5 pagesA Random-Walk-Down-Wall-Street-Malkiel-En-2834 PDFTim100% (1)

- Instafin LogbookDocument4 pagesInstafin LogbookAnonymous gV9BmXXHNo ratings yet

- HOTC 1 TheFoundingoftheChurchandtheEarlyChristians PPPDocument42 pagesHOTC 1 TheFoundingoftheChurchandtheEarlyChristians PPPSuma HashmiNo ratings yet

- Catalogo 4life en InglesDocument40 pagesCatalogo 4life en InglesJordanramirezNo ratings yet

- Burton Gershfield Oral History TranscriptDocument36 pagesBurton Gershfield Oral History TranscriptAnonymous rdyFWm9No ratings yet

- Hays Grading System: Group Activity 3 Groups KH PS Acct TS JG PGDocument1 pageHays Grading System: Group Activity 3 Groups KH PS Acct TS JG PGkuku129No ratings yet