Professional Documents

Culture Documents

New Text Document

Uploaded by

Saurya PrakashOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

New Text Document

Uploaded by

Saurya PrakashCopyright:

Available Formats

if not line: break Student Career Aspirations: the effect of year of study, gender and personality traits University

of Maastricht Faculty of Economics and Business Administration Maastricht, May 2009 Annette Smulders I448168 Master International Business 1st supervisor: Anita van Gils 2nd supervisor: Martin Carree Master Thesis 2 Executive summary Bonuses for top managers installing women in top positions , could be the headline of a newspaper today. Multiple companies acknowledge the lack of women in top positio ns and have signed agreements to stimulate the number of women in top management. Many theories have been identified as reasons for the shortfall of women and, in extension to current studies, this research will focus on the career aspirations to top management level or en trepreneurship of students. Ambition is a strong predictor of career success. The aim of this study was to examine the influence of year of study, gender and personality characteristics on career aspirations to top management level or entrepreneurshi p. This study hypothesized that the career aspirations of students would decrease with years o f study, that there are differences in career aspirations between female and male students and that these differences will increase with years of study. Moreover, it was hypothesized tha t personality traits had a positive influence on career aspirations, individually and as a sin gle factor construct. The hypotheses of this research were investigated on a sample of 336 self-reported questionnaires of female and male business and economics students. Exploratory f actor analysis, ANOVA and multiple regression analyses were used to test the research model. The results indicate that years of study has a negative effect on career aspirat ions to top management level or entrepreneurship, indicating that the career aspirations of students decrease when they advance their studies. Contrary to the hypothesis, no signifi cant differences were found between the career aspirations of female and male student s. Furthermore, the analyses revealed the positive influence of personal initiative , risk-taking propensity, competitive aggressiveness, autonomy orientation, need for achieveme nt, extraversion, openness to experience and conscientiousness on career aspirations of students, indicating that internal factors influence students ambition to top management le vel or to start an entrepreneurial business.

Altogether, the results of the study suggest that this research model can be use d to predict career aspirations of students. This model can provide companies and universitie s with a tool to predict potential talents and to invest and guide these students to top posit ions, especially female students. 3 Table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................ ............................................................................ 5 1.1. INTRODUCTION OF TOPIC ..................................................... ......................................................................... 5 1.2. PROBLEM STATEMENT ......................................................... ........................................................................ 8 1.3. RELEVANCE OF THE TOPIC .................................................... ........................................................................ 8 1.4. RESEARCH METHOD ........................................................... ......................................................................... 9 1.5. STRUCTURE OF THE THESIS.................................................... ...................................................................... 9 2. LITERATURE REVIEW OF GENDER AND CAREER ASPIRATIONS .......................... ..................... 10 2.1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. ............................................................................ 10 2.2. CAREER ASPIRATIONS ........................................................ ....................................................................... 10 2.2.1. Definition of career aspirations ........................................ ................................................................. 10 2.2.1. Top level career aspirations and entrepreneurial career aspirations ..... .......................................... 12 2.3. GENDER AND CAREER ASPIRATIONS ............................................. .............................................................. 12 2.3.1. Social structural theory and social role theory ......................... ........................................................ 12 2.3.2. Stereotype activation theory ............................................ .................................................................. 13 2.3.3. Socialization theory .................................................... ....................................................................... 14 2.3.4. Social-cognitive career theory .......................................... ................................................................. 14 2.3.5. Conclusion .............................................................. .......................................................................... 14 2.4. DETERMINANTS OF CAREER ASPIRATIONS ........................................ .......................................................... 15 2.5. CHANGES IN CAREER ASPIRATIONS ............................................. ............................................................... 17 2.5.1. Gender and year of study ................................................ ................................................................... 17 2.5.2. Career development theory................................................ ................................................................ 18 2.6. CONCLUSION ................................................................ ............................................................................. 18 3. PERSONALITY TRAITS .......................................................... .................................................................... 19 3.1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. ............................................................................ 19 3.2. ENTREPRENEURIAL ORIENTATION................................................ .............................................................. 19 3.2.1. Introduction to the Entrepreneurial Orientation construct ...............

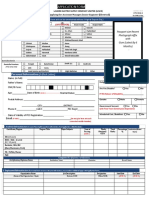

................................................ 19 3.2.2. Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation................................... .......................................................... 20 3.2.3. Dimensions of the Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation ................ ............................................... 20 3.3. ENTREPRENEURIAL TRAITS..................................................... .................................................................... 22 3.3.1. Internal locus of control ............................................... ..................................................................... 22 3.3.2. High need for achievement ............................................... ................................................................. 22 3.3.3. Risk-taking propensity .................................................. ..................................................................... 22 3.4. TOP MANAGEMENT TRAITS ..................................................... .................................................................... 23 3.5. A PERSONALITY TRAITS MODEL................................................. ................................................................. 25 3.5.1. Manager vs. Entrepreneur ................................................ ................................................................. 25 3.5.2. Overview of the personality traits ...................................... ................................................................ 25 3.6. CONCLUSION ................................................................ ............................................................................. 26 4. MODEL AND HYPOTHESES ........................................................ .............................................................. 27 4.1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. ............................................................................ 27 4.2. MODEL ..................................................................... ................................................................................ . 27 4.3. HYPOTHESES ................................................................ ............................................................................. 28 4.4. RESEARCH MODEL ............................................................ ......................................................................... 34 4.5. CONCLUSION ................................................................ ............................................................................. 34 5. METHODOLOGY ................................................................. ........................................................................ 35 5.1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. ............................................................................ 35 5.2. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ....................................................... ....................................................................... 35 5.3. RESEARCH TYPE ............................................................. ........................................................................... 36 5.4. SAMPLE .................................................................... ................................................................................ . 37 5.5. DATA COLLECTION ........................................................... ......................................................................... 37 5.6. MEASUREMENT OF VARIABLES................................................... ................................................................ 38 5.6.1. Independent variables ................................................... ..................................................................... 38 5.6.2. Moderating variable ..................................................... ..................................................................... 42 4 5.6.3. Outcome variable ........................................................ ..................................................................... 42 5.6.4. Control variables ....................................................... ........................................................................ 43

5.7. CONCLUSION ................................................................ ............................................................................. 44 6. RESULTS ..................................................................... ................................................................................ .. 46 6.1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. ............................................................................ 46 6.2. PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS ...................................................... ...................................................................... 46 6.2.1. Descriptive statistics .................................................. ........................................................................ 46 6.2.2. Career aspirations ...................................................... ....................................................................... 49 6.2.3. Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation................................... .......................................................... 50 6.2.4. Entrepreneurial Traits .................................................. ..................................................................... 51 6.2.5. Managerial Traits ....................................................... ....................................................................... 52 6.2.6. Control variables ....................................................... ........................................................................ 52 6.2.7. Ambition ................................................................ ........................................................................... 54 6.3. HYPOTHESES TESTING ........................................................ ....................................................................... 54 6.4. CONCLUSION ................................................................ ............................................................................. 59 7. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ................................................... .......................................................... 60 7.1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. ............................................................................ 60 7.2. DISCUSSION OF RESULTS ..................................................... ....................................................................... 60 7.3. LIMITATIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ......................... .......................................... 64 7.4. IMPLICATIONS OF THE RESEARCH .............................................. ................................................................. 65 7.5. THESIS CONCLUSION ......................................................... ........................................................................ 67 8. REFERENCE LIST .............................................................. ......................................................................... 69 APPENDIX A QUESTIONNAIRE ....................................................... .................................................... 77 APPENDIX B PRINCIPAL COMPONENT EXPLORATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS ..................... 83 B.1. CAREER ASPIRATIONS ........................................................ ....................................................................... 83 B.2. INDIVIDUAL ENTREPRENEURIAL ORIENTATION .................................... ..................................................... 85 B.3. ENTREPRENEURIAL TRAITS .................................................... ................................................................... 86 B.4. MANAGERIAL TRAITS ......................................................... ...................................................................... 89 B.5. ROLE CONFLICT ............................................................. ........................................................................... 91 APPENDIX C NORMALITY TESTS ..................................................... ................................................. 92 C.1. CAREER ASPIRATIONS ........................................................ ....................................................................... 92 C.2. NORMALITY TESTS IEO .......................................................

...................................................................... 92 C.3. MANAGERIAL TRAITS ......................................................... ...................................................................... 93 C.4. ROLE CONFLICT ............................................................. ........................................................................... 93 APPENDIX D ANALYSES ............................................................ ............................................................ 94 D.1. ANOVA ROLE-CONFLICT CAREER ASPIRATIONS .................................... ................................................ 94 D.2. ANOVA NATIONALITY CAREER ASPIRATIONS ...................................... .................................................. 94 APPENDIX E ANALYSES ............................................................ ........................................................... 95 E.1. ANOVA - ROLE CONFLICT ..................................................... ................................................................... 95 E.2. ANOVA - ROLE MODEL ........................................................ .................................................................... 95 E.3. ANOVA - NATIONALITY ....................................................... .................................................................... 96 APPENDIX F CROSSTABULATIONS .................................................... ............................................... 97 APPENDIX G INDEPENDENT-SAMPLES-T-TEST .......................................... ................................... 99 5 1. Introduction 1.1. Introduction of topic Since 2003, women participation in businesses, universities and politics is a re turning news item in The Netherlands (www.elsevier.nl; www.intermediair.nl). Currently, a poi nt of discussion in the Dutch government is whether or not to take on a code or policy that instructs companies to have a certain percentage of women active in top positions. Several political parties are working on a new bill forcing companies to implement the proposed qu ota and threaten to shut down non-cooperative companies. These measures are very drastic , and clearly show the severity of this issue in The Netherlands. In America, the numb er of women in top executive positions is also a hot topic. Helfat, Harris and Wolfson (2006 ) studied the participation of women and men in the top Executive ranks of U.S. Corporations i n order to estimate the future women at top executive positions. Their findings show that t he percentage of women CEO s is relatively low, only 8,25% or 821 executives of the total of 9.9 50 executives are women. Furthermore, 48 percent of all Fortune 1000 companies had no women as executives (Helfat et al., 2006). The percentage of women as executives (i.e. in the board of directors) in compan ies in the Netherlands was 4,8% in 2007 (Van Riet, 2007). Although this percentage has not been measured yet in 2008, one can expect the percentage is still less then 10% today . Nowadays, the number of female students at university level does no longer stay behind the number of male students at universities (CBS,2008). Therefore, the education level of men

and women can be assumed to be the same. So, if education is no longer a factor for the la ck of women executives, than what are the reasons for the lack of women executives in large companies in the Netherlands? Several authors found identical reasons for the lack of women in top executive p ositions. Powell and Butterfield (1994) consider the glass ceiling effect as one of the reas ons why women do not reach executive levels. The glass ceiling phenomenon represents the obstacles women face on their way to the top level of organizations (Powell and Butterfiel d, 1994; McDonald, 2004). While the glass ceiling effect can exist at every level in the organization, nowadays this phenomenon is mainly used to explain the difficulties women face i n reaching the executive positions. Today, due to changing company policies and government guidelines, the glass ceiling effect is declining. Powell and Butterfield (1994) even state that 6 the glass ceiling does not exist anymore and women have favorable positions and may be subject to extra commitment in order to create equal opportunities within the co mpany. Despite today s change in company policies and tomorrow s government guidelines, the Grand Thornton International Business Report (2009) shows that 85 percent of all companies in the Netherlands still have no women in senior management positions. In compar ison, on a global level 34 percent of all companies still have no women in senior managemen t positions. Hence, the number of women at top positions in The Netherlands is ranked one of the lowest in the world. However, one could question whether the aforementioned glass ceili ng phenomenon is still the most prominent theory that explains this number of women as top executives? The media is focusing on a new explanation for the lack of women on top position s. Several newspapers and magazines dedicate articles, pages or even a whole magazine to th is subject: the (lack of) ambition of women (Fels, 2004). Despite the attention to this subj ect in the media, only a few academic articles are written on this subject. Additional rese arch on career aspirations and its determinants among students can clarify this subject. Hence, this paper will focus on individual factors (i.e. career aspirations or a mbition) and certain characteristics of people that will enhance the ambition to top manageme nt or to start an entrepreneurial business. Previous research by Judge, Cable, Boudreau and Bre tz (1995) found that executives who displayed a desire to get ahead (Judge et al., 1995, p. 509) are more likely to attain objective career success (i.e. measured by salary and prom otions). Researchers found a positive relationship between ambition and career success an

d, according to Judge et al. (1995), ambition can be considered one of the best predictors of career success (Cox and Cooper 1989; Judge et al., 1995). Additionally, Danziger and Eden (2007 ) argue that differences between the sexes in aspirations and career preferences can lea d to eventual differences in career accomplishment, even with the same education level. Firstly, career aspirations can be considered an important indicator of a future career, given that a lack of motivation and ambition will not lead to a top position. Since a high level of career aspirations does not solely predict career success within large organizat ions, but can also indicate an aspiration to become successful by starting an own entrepreneur ial business, this research will not only focus on aspirations to become a top manager, but al so includes the aspirations to become an entrepreneur of an independent business. 7 Career aspirations can be defined as a construct embodying individuals occupationa l identity and desired career goals (Danziger and Eden, 2006). Given the same level of education, career aspirations of male and female should be similar; however, sev eral authors concluded that occupational aspirations formed at the beginning of the education al process are subject to realism during the final stage of the educational process (Danziger a nd Eden, 2007). A number of studies reveal that women tend to temper their career aspirations du ring the final stages of their education (Harmon, 1989; Danziger and Eden, 2007). The concept o f career aspirations and its development over the years of study is worth exploring in fu rther detail. Additionally, people need to have a drive to reach the top in the organization o r to start an entrepreneurial business. Besides experience and knowledge, people need to posse ss certain characteristics to reach the top executive level or to start an entrepreneurial business. For example, Dulewicz and Herbert (1999) found that the majority of the senior manag ers are more likely to take risks, are more decisive and forceful and show more energy a nd initiative. Furthermore, Lumpkin and Dess (1996, 2005) developed the entrepreneurial orienta tion construct, which refers to a frame of mind and a perspective about entrepreneursh ip (Dess and Lumpkin, 2005, p.147) or a mindset that is necessary to make progression. Lu mpkin and Dess (1996) identified five dimensions of the Entrepreneurial Orientation: innov ativeness, proactiveness, autonomy, competitive aggressiveness and risk-taking (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996; Richard et al. 2004). Although the Entrepreneurial Orientation is usually used to measure a corporate environment, Krauss et al. (2005) expanded the original entr epreneurial

orientation construct to a psychological concept in order to focus on an individ ual (i.e. entrepreneur or manager). The individual entrepreneurial orientation adds two ne w variables to the original construct: namely the learning and the achievement orientation ( Krauss et al., 2005), and can be used to identify an entrepreneur that is more likely to have a successful business. However, the individual entrepreneurial orientation model is not the only model that evaluates individuals characteristics. Two other models frequently used to assess individua ls personality characteristics in order to identify the prospective entrepreneurs a nd/ or managers are the entrepreneurial traits model and the five factor model. One could argue that the personality characteristics have an influence on the ca reer aspirations of both male and female students, however this relation has been largely overloo ked. 8 1.2. Problem statement As aforementioned, many authors concentrated on the reasons for the lack of wome n on top management positions (Powell and Butterfield, 1994; Reinhold, 2005). Despite the importance of ambition in order to reach top level management or to start an ent repreneurial business, only a few authors addressed this issue (Powell and Butterfield, 2003; Danziger and Eden, 2007; Litzky and Greenhaus, 2007). However, ambition can be considered a c rucial element in career attainment, in view of the fact that people who do not aspire to a top management position or to start an entrepreneurial business, will not aim to rea ch that position and, consequently, settle for other options. Taken this into account, the purpose of this study is to investigate the influen ce of year of study and gender on career aspirations, as well as the influence of the personal ity traits on gender and career aspirations. Hence, the problem statement of this thesis is: What is the effect of year of study, gender and personality characteristics on t he career aspirations to top management level or to start an entrepreneurial business? In order to research this question, the thesis will consist of a review of the r elevant literature and an empirical research part. In order to gain a comprehensive insight in the existing literature and to answer the problem statement, the following sub-questions will be addressed: 1. What are the determinants of career aspirations? 2. Specifically, what is the relation between year of study and career aspiratio ns? 3. What is the influence of gender on the relation between year of study and car eer aspirations? 4. Which personality traits can be used to predict high career aspirations? 1.3. Relevance of the topic The aspirations throughout the years of study of students, both male and female, and the

personality traits, can contribute to a model in order to identify future top ex ecutives or entrepreneurs during the years of university. This study will investigate studen ts, both male and female, from different study years in order to identify a pattern of career aspirations. Incorporating personality traits can replenish the model. This model can be used by both 9 universities and companies to identify the prospective top executives or entrepr eneurs in order to invest in these students and subsequently, the potential talents, women and m en, can be prepared and guided towards their goals. 1.4. Research method This thesis will consist of two parts in order to investigate the problem statem ent. First, the existing literature will be reviewed and secondary data will be used to provide a solid, theoretical background for the hypotheses. Secondly, the hypotheses will be cons tructed in the second part of the thesis, which will entail the empirical research. The depende nt variable of this research is career aspirations to top management level or to start an entre preneurial business of university students in order to identify potential top managers/ ent repreneurs. Year of study and personality characteristics are the independent variables of t his research. Gender is both a moderating and an independent variable. Several instruments are used to test the aforementioned variables. The sample contains university students from the f our years of study. To collect the data for this research, a self-reported online questionnai re is filled out by the students. 1.5. Structure of the thesis As stated before, this thesis comprises two parts. The first part of the thesis consists of the literature review, whereas the second part contains the empirical research. First, the literature review includes two chapters, starting with chapter two. C hapter two will contain the theoretical background of career aspirations and will elaborate on t he history, definition and scope of career aspirations. Furthermore, this chapter discusses the influence of gender and year of study on career aspirations of students. The third chapter ex plains the individual entrepreneurial orientation construct, the entrepreneurial traits and the managerial personality traits. Moreover, the literature review leads to the formation of th e hypotheses and the introduction of the research model; the basis of the empirical research as e laborated upon in chapter four. Subsequently, chapter five contains the methodology description which is used to test the hypotheses of the research. The data are analyzed in the sixth chapter and the results are explained. In addition, the results are interpreted and discussed in the seventh

chapter. Finally, the implications and limitations of the research and the recom mendations for future research are discussed and are followed by a conclusion. 10 2. Literature review of gender and career aspirations 2.1. Introduction This chapter introduces the background of career aspirations and its relation to gender. It starts with an overview of the definitions of career aspirations and a formulati on of career aspirations as used throughout this paper. Furthermore, the relation between gen der and career aspirations will be elucidated using several established theories from the liter ature. The chapter continues with the determinants of career aspirations in order to unders tand the concept and its variables. In addition, the theoretical background of the change s in career aspirations during college years will be discussed. Finally, a conclusion of the chapter is drawn. 2.2. Career aspirations In this section, the definition of career aspirations, based on Gottfredson s (198 1) article on the development of career aspirations will be discussed. 2.2.1. Definition of career aspirations Throughout the years, career aspirations have been described differently by seve ral authors. Gottfredson (1981) wrote an article about the development of occupational aspira tions and she identified four stages of development throughout childhood years. The first stage (age 35) is orientation to size and power, followed by the orientation by sex roles (a ge 6-8). The third stage is the orientation to social valuation at age 9-13. The fourth and f inal stage is the orientation to the internal, unique self, starting from the age of 14. Although this paper will address university students (age approximately 18-25), and additional factors de termine the career aspirations, Gottfredson emphasizes the importance of childhood in future occupational aspirations. Gottfredson also identified two types of aspirations: the realistic aspirations and the idealistic aspirations. This theory is used by many authors during the formu lation of their definition of career aspirations (Powell and Butterfield, 2003; Danziger and Ede n, 2006; Litzky and Greenhaus, 2007). According to Danziger and Eden (2006), career aspiration is a construct embodying individuals occupational identity and desired career goals (Danziger and Eden, 200 6, p.115). They also argue that career aspirations are linked to individuals expectat ions of occupations and jobs and the perceptions of the individuals are ideas and judgment s, which are a product of a mental process of organizing, integrating, and recognizing ph enomena 11 (Danziger and Eden, 2006, p.115). In accordance with the theory by Gottfredson (

1981), this definition recognizes the idealistic aspirations (i.e. the desired career goals) and the development of career aspirations over years (i.e. mental process). The perceive d difference between these two types of aspirations is referred to as the expectation gap by Da nziger and Eden (2006). In accordance with the two different types of aspirations of Gottfredson (1981), Litzky and Greenhaus (2007) make a distinction between desired aspirations and enacted aspi rations, where enacted aspirations represent the behavioral manifestations of desired aspi rations (Litzky and Greenhaus, 2007, p. 639). Although this shows similarities with the two components of Gottfredson, the realistic and idealistic aspirations, this defini tion shows a clear distinction between the attitudinal and the behavioral component (Litzky a nd Greenhaus, 2007). The attitudinal component is able to enact as motivation to reach a speci fic goal. Furthermore, the behavioral component of career aspirations comprises the actual plans and strategies in order to achieve the desired goals (Litzky and Greenhaus, 2007). Moreover, the research by Nauta, Epperson and Kahn (1998) investigated the predi ctors of higher level career aspirations (i.e. aspirations to a higher level within a spe cific field) and therefore adopted a slightly different definition of career aspirations. They de fine career aspirations as the extent to which people aspire to leadership or advanced positi ons within their chosen occupation (Nauta et al., 1998, p. 483). Litzky and Greenhaus (2007) have a similar definition of career aspirations which emphasizes the advancement to a h igher level (i.e. senior management level) within an organization in contrast to an aspirati on to a specific field. The aforementioned definitions of career aspirations have several items in commo n. First, career aspiration embodies at least two components, an attitudinal and a behavio ral component, whereby the attitudinal component represents the ideas and dreams (i. e. the idealistic aspirations) and the behavioral components the actual actions a perso n takes in order to fulfill the dream (i.e. the realistic aspirations). Second, career aspiration is a construct applicable on an individual and differs among people. Finally, career aspiration s stimulate individuals to work hard and dedicated in order to reach certain goals. Since th is thesis focuses on the ambition to reach top management level or to start their own busi ness, the integration of this type of aspirations is important, like Nauta et al. (1998) a lso included this type of aspiration in their definition of career aspirations. Therefore, in this thesis, the

definition of career aspirations used is a construct embodying an individuals dre ams and 12 desired career goals and the extend to which individuals intend to take action t o advance to a higher level within an organization or to start their own business (Nauta et al. , 1998; Powell and Butterfield, 2003; Danziger and Eden, 2006; Litzky and Greenhaus, 2007). 2.2.1. Top level career aspirations and entrepreneurial career aspirations Although gender differences in career aspirations is an extensively researched t opic in the academic literature (Danziger and Eden, 2007), ambition to aim for a top level c areer has not been researched comprehensively. Given that high career aspirations can either l ead to a top management position, but eventually also to an entrepreneurial career, this pape r will not make a distinction between managers and entrepreneurs. Hence, this paper will pr imarily focus on career aspirations to reach top level management positions or to start their own business in order provide more insight in this topic. 2.3. Gender and career aspirations Career aspirations have been studied regularly in the vocational literature, how ever, the majority of the literature focused on the aspirations to select a specific caree r (i.e. scientist, biologist, and engineer) (Harmon, 1989; Nauta et al., 1998). Throughout the year s, many authors researched gender-related differences in career aspirations from differe nt viewpoints and, therefore, several theories can be used to explain the gender differences ( Eagly and Wood, 1999; Danziger and Eden, 2007), namely the social structural and social ro le theory, the stereotype activation theory, the socialization theory and the social-cognit ive career theory. These perspectives will be discussed in the next sections. 2.3.1. Social structural theory and social role theory Social structural theory is a theory covering more sub theories regarding sex di fferences. The social structural theory states that there is a main cause for the sex differenc es; the concentration of men and women in different social roles. The most important the ory of the social structural theory in the context of gender differences in career aspirati ons is the social role theory. This theory to explain gender differences in behavior is developed by Eagly (Feingold, 1994; Eagly and Wood, 1999). The social role theory hypothesizes that sex differences in social behavior stem from gender roles, which dictate the behavio rs that are appropriate for males and females (Feingold, 1994, p. 430). Accordingly, the pers on s personality may change and, consequently, the responses to personality tests and items may change (Feingold, 1994). Eagly and Wood (1999) and Franke (1997) state that men and 13

women have a tendency to adjust their behavior according to the characteristics of the social role they occupy. Consequently, men have a tendency to enter masculine or male-d ominated occupations, while women tend to aspire to enter feminine or female-dominated oc cupations (Powell and Butterfield, 2003). Former researchers found differences between the aspirations of men and women, with men tending to aspire a male-dominated occupation, wherea s women tend to aspire a female-dominated occupation (McNulty and Borgen, 1988; Po well and Butterfield, 2003). Although the differences between aspirations of men and women reduce and more women enter male-dominated occupations, there are still a few wo men in top management positions (Powell and Butterfield, 2003). The processes of social rol e theory, unconsciously, influence the career aspirations of men and women to top manageme nt positions. Hence, gender differences in career aspirations to top management pos itions can be (partly) explained by the social role theory. 2.3.2. Stereotype activation theory Many scholars address gender stereotyping in relation to moving up the ladder wi thin organizations and entrepreneurial firms (Heilman, 2001; Heilman and Okimoto, 200 7; Gupta, Turban and Bhawe, 2008). Gupta et al. (2008) investigated what the impact of an implicit or explicit activation of gender stereotypes is on men s and women s intention to pursu e a traditionally masculine career and concluded that the activation of stereotypes indeed had impact on the intentions. Gender stereotypes are widely shared in cultures (Heil man, 2001; Gupta et al., 2008) and often affect behavior and attitudes of individuals by un conscious internalization of the stereotypes (Feingold, 1994; Eagly and Wood, 1999; Gupta et al., 2008). Subsequently, people are likely to behave according to the stereotype and perfor m tasks that are positively interconnected with their gender and tend to avoid tasks that are not interconnected with their gender (Heilman, 2001; Gupta et al, 2008). Furthermore , individuals are unconsciously influenced by well-known stereotypes if the stereotype is well -known in society (Gupta et al., 2008). Although there is not yet investigated, besides Gu pta et al. (2008), whether gender stereotyping has an effect on career aspirations of men a nd women, one could assume the stereotype activation theory can also have an influence on the gender differences in career aspirations for top level positions, because top managemen t positions can be considered achievement-related and therefore masculine (Gupta et al., 200 8). 14 2.3.3. Socialization theory

In accordance with the social role theory, the socialization theory also argues that gender differences in career aspirations are caused by processes during the life of men and women. However, the socialization theory states that a permanent gender identity is esta blished through the socialization processes people undergo in childhood (Franke, 1997, p. 920) and, contrary to the social role theory, gender will remain the primary social categor y that shapes people s values, perceptions, work-relates attitudes and behavior (Danziger and Ede n, 2007, p. 131). Therefore, it is very difficult to change gender identities and the correspondin g attitudes and behavior. As aforementioned, career aspirations also have an attitudinal compone nt and a behavioral component, and according to the socialization theory, changing attitu des and behavior learned through childhood is very difficult. Another resemblance betwee n the social role theory and the socialization theory is that people learn certain gender rol es in their childhood, which affect the values and attitudes towards work. Hence, the behavi or learned in childhood is likely to affect the career aspirations of women (Danziger and Eden , 2007). Subsequently, since these attitudes and behaviors are difficult to change, there remains a difference between the career aspirations of men and women. 2.3.4. Social-cognitive career theory Another theory trying to explain differences in career development is the social -cognitive career theory by Lent and Brown (1996). The theory helps to explain individual d ifferences in occupational choices, interest and performance by considering the individual as the active shaper of his or her experience (Lent and Brown, 1996, p.319). The theory also in cludes the effect of other individuals and aspects in the environment, like gender and ethn icity (Lent and Brown, 1996). Hence, there is an interaction between various variables. The soci al cognitive career theory argues there are three linked variables that can help individuals to control their own behavior: self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and personal goals (Len t and Brown, 1996, p. 312). Differences between gender in career aspirations are opera ted through the learning processes of the experiences that give rise to certain beliefs (i.e . role-modeling, stereotyping). 2.3.5. Conclusion In conclusion, there are many theories explaining the differences in career aspi rations between men and women. These theories can help to explain the final results of this pape r. Although 15 all the theories have different viewpoints, there is one common factor; the diff erences

between gender result from processes during a specific period in individuals live s, mostly childhood. Moreover, individuals are influenced by several factors during their lives that affect their ideas and choices. These determinants will be discussed in the next chapter. 2.4. Determinants of career aspirations In this section, the determinants of career aspirations will be discussed. Sever al authors investigated the factors that influence career aspirations of men and women (Nau ta et al., 1998; Wall, Covell and Macintyre, 1999; Powell and Butterfield, 2003; Gupta et a l. 2008). In order to understand the construct of career aspirations completely and to be abl e to explain the outcomes of this research, the determinants of career aspirations will be elucid ated. Social support A determinant of career aspirations is the social support of the individual from the environment. Wall et al. (1999) identified three different types of social suppo rt: family, peers and teachers (i.e. school). Family support has shown to have the most influence on the individuals perception of opportunity, especially for males (Wall et al., 1999). This in turn has an effect on the education and career expectations and aspirations of the in dividual. Peers and teachers showed to have an influence on the perception of opportunity, but o nly for women. Consequently, social support, although there are gender differences, has an (indirect) influence on the career aspirations of people. Career expectations Building on the stereotype activation theory, people learn specific roles, stere otypes and behavior fitting their gender type. According to these theories, people adjust t heir expectations. The effect of career expectations on the career aspirations has be en researched by Wall et al. (1999), and they found there is a significant relation between ca reer expectations and career aspirations. However, women tend to temper their aspirat ions as a result of their career expectations. Therefore, the relationship found by Wall e t al. (1999) is not a positive relationship. These authors explain this phenomenon to be influen ced by history and state that women believe there are limits on their expectations to the possi bilities to achieve top level positions. Hence, career expectations of women tend to have a negative 16 influence on career aspirations of an individual. However, career expectation is not the only determinant of career aspirations. Role modeling Another determinant of career aspirations is role modeling. According to the res earch of Nauta et al. (1998), role modeling has an effect on the (higher) career aspirati

ons of men and women. Following the social-cognitive career theory by Lent and Brown (1996), th e observation of role models is a learning process and can have an influence on ca reer outcomes (Nauta et al., 1998). A role model can be defined as a person whose life and acti vities influence another person in some way (Nauta et al., 1998, p. 484). Van Auken and Stephens (2006) build upon Wood and Bandura s (1989) theory and state that a role model can influence an individual in three ways. Above all, a role model influences throug h mastery of experiences (Van Auken and Stephens, 2006, p. 158) or, in other words, role model s can show repetitive success. Furthermore, an individual can learn from its role mode l by observation rather than from a direct contribution of the role model (Nauta et a l., 1998; Van Auken and Stephens, 2006). Finally, a role model is able to persuade an individu al that he/she is able to perform certain tasks and therefore give the person confidence. Van A uken and Stephens (2006, p. 158) call this social persuasion . These authors also state that role models have the ability to change attitudes and behavior of a person and, consequently, role models can change the perception of the person of its ability to be successful in a new business. One could assume that if the role model has the ability to change entrepreneurial in tentions, a role model could also change a person s career aspirations. Hence, role modeling can ha ve a positive influence on the career aspirations of individuals. Ability and self-efficacy Though many of the aforementioned determinants are environmental factors, this d eterminant of career aspirations highlights the importance of the individuals beliefs and c onfidence. Nauta et al. (1998) not only investigated the effect of role models on higher le vel career aspirations, but they also investigated the influence of ability on career aspir ations, mediated by self-efficacy. According to the social-cognitive theory by Wood and Bandura ( 1989) and Lent and Brown (1996), a person s ability has an influence on the career outcomes. Moreover, the grade point average of college students has shown to have a positive effect on the higher level career aspirations (Nauta et al., 1998). However, the ability of an indivi dual does not solely predict the higher level career aspirations, because the individual has t o believe his or 17 her ability to successfully execute tasks. Nauta et al. (1998) and Lent and Brow n (1996) refer to this as self-efficacy. Therefore, Nauta et al. investigated the ability-selfefficacy pathway to influence higher level career aspirations and demonstrated that self-efficacy in deed mediates the relationship between ability and career aspirations. Thus, the ability of a

person has an influence on the career aspirations, but is mediated by the person s self-efficacy . In conclusion, there are many factors that have an influence on career aspiratio ns of individuals. All these different determinants play an important role for the fut ure of the individual. Although many factors are environmental and learned over time, caree r aspirations of people can still be adjusted over time, since people gather new information, meet new people and learn new perspectives. The next part of this chapter will address ch anges in career aspirations over time. 2.5. Changes in career aspirations The construct of career aspirations is subject to change, since people adjust th eir expectations and goals over time. In this thesis, the change of career aspirations throughout university years will be investigated. This part of the chapter will elucidate upon gender and career aspirations and explains the relevance of the career development theory (McNulty and Borgen, 1988; Lent and Wortington, 1999). 2.5.1. Gender and year of study Danziger and Eden (2007) investigated whether the occupational aspirations of bo th male and female students changes throughout college. While the career aspirations in the first college year are identical among male and female students, they found a decrease in care er aspirations over the following study years, with a stronger decrease of the career aspiratio ns of the female students. McNulty and Borgen (1988) also state that occupational aspirations go through various stages. The decrease of the career aspirations of women can explain the lack of women at top management positions. Several authors addressed this issue and foun d changes among career aspirations to top management of men and women (McNulty and Borgen, 1988; Harmon, 1989; Powell and Butterfield, 2003; Danziger and Eden, 2007). In accordance with the results from the study by Danziger and Eden (2007), one c ould assume that the career aspirations to top management are similar among male and female first-year university business students. First year students do not yet have realistic idea s about their future occupation and therefore often aspire occupations with high status and re sponsibility, 18 thus have aspirations to top management positions. However, during the following study years, people become more familiar with the business world and the responsibilit ies of top management positions and reassess their situation, which can result in an adjust ment of their career aspirations. Their previous aspirations can be seen as unrealistic or nave (Harmon, 1989; Danziger and Eden, 2007). Additionally, one could argue that female studen

ts during their final year (i.e. the master program) may realize the future conflict betwe en work life and family and adjust their expectations. Thus, this realism can result in a change of career aspirations, and as aforementioned, especially among female students. This pheno menon is also called the career development theory (McNulty and Borgen, 1988), which will shortly be discussed in the next section. 2.5.2. Career development theory Although the career development theory is a very broad theory and has several ap proaches (Lent and Worthington, 1999), this theory can be used to disentangle the aforeme ntioned phenomenon. Career development theory assumes that individuals career aspirations become more realistic and crystallized as they approach their senior year in sch ool (McNulty and Borgen, 1988, p. 219). According to Gottfredson (1981), people adjust their vocational aspirations by the job accessibility factors and the perception of opportunity. The job accessibility factors mostly affect the implementation and not necessarily the f ormulation of aspirations. However, the perception of opportunity does have an effect on the a spirations in that the individuals will adjust their aspirations according to their perception op opportunity. The perception of opportunity and the perceived barriers are expected to have an influence on the career expectations and therefore on the career aspirations of individuals ( Gottfredson, 1981). Consequently, people will reflect their possibilities and preferences and will not waste time on poor bets (Gottfredson, 1981, p.570). People often need to compromise as t hey discover the barriers to their preferences. Subsequently, this reality check cau ses women to adjust their career aspirations in order to provide a compatible match with marri age and family responsibilities (Whitmarsh et al., 2007, p.231). 2.6. Conclusion This chapter discussed in depth the definition of career aspirations, the main t heories explaining gender differences in career aspirations, the determinants influencin g aspirations and the reason for changes in career aspirations during university years. Finall y, throughout the chapter it has become clear there are many factors influencing career aspira tions. 19 3. Personality traits 3.1. Introduction In the previous chapter, the relation between gender and career aspirations is d iscussed extensively. In this chapter, the relation will be complemented by a new variabl e; the personality traits. To define this new variable, a construct will be developed b y combining the entrepreneurial orientation literature, the entrepreneurial traits literature an

d the top management literature. From this broad range of literature, the most suitable va riables will be subtracted. In the following sections, different types of personality models wil l be discussed and evaluated to identify the personality traits that are more predictive of hig h career aspirations than other traits. Personality traits are propensities to act. Differ ent propensities may facilitate or impede business owners actions and behaviors. Therefore, we ass ume that personality traits are predictors of entrepreneurial behavior (Rauch and Frese, 2 007, p.355). Following the reasoning of Rauch and Frese (2007) one could assume that personal ity traits also predict the behavior of managers. 3.2. Entrepreneurial Orientation In order to identify personality characteristics to enhance the career aspiratio ns to top management level positions, the individual entrepreneurial orientation will be u sed. First, the entrepreneurial orientation construct is elaborated upon and the five dimensions are discussed. Moreover, the psychological concept of the EO and the two additional dimensions are clarified. 3.2.1. Introduction to the Entrepreneurial Orientation construct Lumpkin and Dess (1996, 2005) developed the entrepreneurial orientation (EO) con struct, derived from the strategic management literature, to access the processes, practi ces, and decision-making activities that lead to new entry (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996, p. 136 ). The EO is a strategy-making practice and represents the intentions and actions of the m ost important persons within the firm, often the entrepreneur. The EO of a firm is often used to predict or explain the success of the new venture. The entrepreneurial orientation construc t is composed of five dimensions; innovativeness, proactiveness, risk-taking, competitive aggr essiveness and autonomy. Although a firm does not need to exceed in every dimension, the fi ve dimensions interact together to enhance the performance of the firm. Hence, a fi rm that 20 exceeds in every dimension is expected to reach a high performance level (Dess a nd Lumpkin, 2005). 3.2.2. Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation Though this paper will not focus on firm-level behavior, the entrepreneurial ori entation can be used as an initial concept to assess characteristics of people. Krauss et al. (2 005) did exactly this and turned the entrepreneurial orientation construct into a psychological c oncept; the individual entrepreneurial orientation. These authors state that the EO is basic ally a psychological evaluation of an individual (i.e. the entrepreneur), since the EO is measured by

self-reports of individuals. The psychological concept of the EO stresses the imp ortance of the owner/manager/founder of a firm (Krauss et al., 2005, p. 317), since this per son is responsible for the strategy and the decision-making of the firm. Krauss et al. (2005) added two dimensions to the original five dimensions (i.e. learning orientation and ac hievement orientation) and investigated the relationships between the individual EO and bu siness performance. The different dimensions and the effect on business performance wil l be discussed in the next section. 3.2.3. Dimensions of the Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation Innovativeness Innovation is an important factor for an entrepreneur, because it can provide th e firm a competitive advantage. Innovativeness implies that one has a positive mind-set to wards new ideas with regard to products, services, administration, or technological proces ses (Krauss et al., 2005, p.320). Hence, the entrepreneur or manager needs to be open-minded an d welcome new ideas in order to maintain the competitive advantage and, consequently, a hi gh business performance level. Proactiveness/ personal initiative Personal initiative is a proactive, self-starting, and persistent orientation tha t attempts to shape environmental conditions (Krauss et al., 2005, p.321) and is an extension o f the original proactiveness dimension. The business owner or manager needs to seize n ew opportunities and anticipate to (future) changes in the environment. An orientat ion that looks forward is important to maintain the competitive advantage and, therefore, a suc cessful business (Dess and Lumpkin, 2005). 21 Risk-taking Although there is little evidence for the positive relationship between risk-tak ing propensity and business success, a risk-taking orientation is assumed to be necessary to su rvive in a competitive environment (Krauss et al., 2005; Dess and Lumpkin, 2005; Kropp et a l., 2006). According to Krauss et al. (2005), risk-taking orientation will help the entrepr eneur to take on inevitable risks and challenges. Therefore, taking risks can be assumed to bring companies a step forward. Competitive aggressiveness Competitive aggressiveness refers to a firm s effort to outperform its industry riv als (Dess and Lumpkin, 2005, p.151). On an individual level, the entrepreneur should enjoy the competition and needs to have a drive to win the battle. From this viewpoint, co mpetitive aggressiveness is necessary to have a successful business performance. Autonomy orientation

An autonomy orientation highlights the importance of the individual decision mak ing and the dislike of following orders top-down. Managers and entrepreneurs with a high aut onomy orientation are motivated to fulfill their own dreams, ideas and visions (Krauss et al., 2005). Learning orientation In the past decade, learning orientation has become more important within compan ies. Learning implies the development of more adequate mental models and is crucial to making successful decisions (Krauss et al., 2005, p. 319). People learn from their exper iences and can use that information to prevent the same mistakes in the future. Since there are many topics that are not addressed during university, they need to learn from the exp eriences in the field independently to succeed in business (Krauss et al., 2005; Kropp et al., 2 006). Achievement orientation To reach certain goals, like a successful business or top position, people need to have a certain drive. Achievement orientation represents this drive to focus on a dream and wor k hard to reach it. According to Krauss et al. (2005) people with an achievement orientati on are better in non-routine tasks and will take responsibility for their actions and results. They will try to improve themselves and set high goals, which will lead to better performances. 22 In conclusion, the seven dimensions of the psychological entrepreneurial orienta tion can be used to assess characteristics of individuals. In this thesis, the individual en trepreneurial orientation will be used to assess the characteristics of students that enhance the career aspirations to top management level or to start their own business. 3.3. Entrepreneurial traits Although there are mixed empirical results of the influence of personality chara cteristics on entrepreneurial activity, recent research tries to show the importance of person ality characteristics on entrepreneurial intentions and success (Korunka, Frank, Luege r and Mugler, 2003). Therefore, the three most relevant personality traits of entrepre neurs will be discussed shortly. 3.3.1. Internal locus of control According to the theory of locus of control, there are two types of individuals; the internals and the externals. On the one hand, the externals believe that they cannot contr ol everything and many things happen as a result of fate or luck. On the other hand, the inter nals believe they can control the future through their own actions. Obviously, entrepreneurs need to be internals, since they need to believe they can change the future of the business and be successful. Therefore, one could assume an entrepreneur has an internal locus of control

(Begley and Boyd, 1987; Dollinger, 2003). 3.3.2. High need for achievement In accordance with the achievement orientation of the individual entrepreneurial orientation, a high need for achievement means a desire to set their own goals, solve their own problems and to receive feedback on their performance (Dollinger, 2003). Furthermore, the y like to reach their goals by using their own capacities. Entrepreneurs would be more lik ely to set up their own challenging goals and will work hard to achieve these goals (Begley an d Boyd, 1987; Wu, Matthews and Dagher, 2007). 3.3.3. Risk-taking propensity According to Dollinger (2003) and Begley and Boyd (1987), an entrepreneur can be considered as a risk-taker, since starting a new venture brings along many risks and uncertainties. However, researchers have failed to provide empirical evidence fo r the risk23 taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Research shows no difference between the ris k-taking propensity of entrepreneurs and managers (Dollinger, 2003). In conclusion, the three entrepreneurial traits as states above are frequently u sed to identify entrepreneurs (Dollinger, 2003) by their characteristics. In order to identify t he personality traits that have a positive influence on career aspirations, this thesis will te st the three entrepreneurial traits of students. 3.4. Top management traits Finally, in order to compose a new personality traits construct, personality cha racteristics need to be identified from the top management literature. Although there is a br oad range of research on top executives, there is limited research on the personality traits necessary to make it to the top level of organizations. Hambrick and Mason (1984) developed t he upper echelons theory in order to focus research on the top executives within organiza tions. The theory contains two parts. The first part of the theory states that executives ac t on the basis of their personalized interpretations of the strategic situations they face (Hambric k, 2007, p.334). The second part of the theory states that these personalized construals a re a function of the executives experiences, values and personalities (Hambrick, 2007, p.334). T he upper echelons theory thus recognizes the impact of personality on performance. Howeve r, this theory does not state which personality traits have a positive effect on the per formance. Therefore, in this paper, the five factor model or the Big Five will be used to identify important personality traits. The five factor Model as revived by McAdams (1992) is a frequently used personality measurement model in the economic literature. Though the five factor model has not been applied to top managers, Cannella and Monroe (1997) re commend

the use of this model for research on top managers. Therefore, in this paper the five factor model will be used to test the personality of students. The five personality dim ensions (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscienti ousness) will be discussed shortly in this section. Neuroticism Neuroticism represents individual differences in adjustment and emotional stabili ty. (Zhao and Seibert, 2006, p.260). People with a high score on neuroticism are tense, ea sily frustrated and unable to deal with stress. Hence, these people have a tendency towards nega tive emotions (McCrae and Costa, 1991; Zhao and Seibert, 2006). Individuals with a lo w score on 24 neuroticism are relaxed, self-controlled and feel secure. Thus, they have a tend ency towards positive emotions (McCrae and Costa, 1991). Extraversion The personality dimension extraversion is the extent to which people are assertiv e, dominant, energetic active, talkative and enthusiastic (Zhao and Seibert, 2006, p.260). Ind ividuals with a high score on extraversion tend to be outgoing, fast-paced, cheerful and seek stimulation and social contact. People with a low score on extraversion are formal, prefers being alone, cautious and serious (McCrae and Costa, 1991). Openness to experience Openness to experience entails intellectual curiosity and the need to explore ne w ideas and experiences (Zhao and Seibert, 2006). People with a high score on openness are i maginative, sensitive, broad-minded and seek novelty and variety. Someone with a low score o n this dimension prefers familiar and routine, factually oriented, narrow in interest a nd avoids (day) dreaming (McCrae and Costa, 1991; Zhao and Seibert, 2006). Agreeableness Agreeableness assesses one s interpersonal orientation (Zhao and Seibert, 2006, p.26 1). Individuals with a high score on agreeableness are trusting, helpful, straightfo rward and have a tendency for positive interpersonal relationships. People with a low score on agreeableness are cynical, suspicious, manipulative and will not cooperate easily (Zhao and Se ibert, 2006). Conscientiousness Conscientiousness, or sometimes called Will to Achieve (Barrick and Mount (1991) , is the fifth personality dimension of the five factor model. An individual with a high score on conscientiousness shows motivation and responsibility, is organized and works ha rd. A person with a low conscientiousness score is unreliable, unorganized and aimless (Barrick and Mount, 1991; Zhao and Seibert, 2006). In conclusion, the five factor model or the Big Five will be used to identify th

e characteristics that increase the career aspirations of students. In contrast to the entrepreneu rial orientation and the entrepreneurial traits, this model has been tested on both managers and entrepreneurs. 25 3.5. A personality traits model In this section, the aforementioned personality traits will be evaluated and the most suitable characteristics for a research on career aspirations to top management or to sta rt an entrepreneurial business will be selected. These selected factors will be put to gether to form the new personality model. 3.5.1. Manager vs. Entrepreneur Although there is a significant amount of research on managers and entrepreneurs , there is little research that compares the two. To identify personality traits that moder ate the relation between gender, year of study and career aspirations to reach top management lev el or to start their own business, the most suitable characteristics of these two literature bo dies will be discussed. Entrepreneurs and managers show significant differences, however ther e are also similarities in personality traits (Malach-Pines, Sadeh, Dvir and Yafe-Yanai, 20 02). Since this paper has a focus on career aspirations of students to reach top level managemen t positions or to start their own business, the primary focus will not be on the differences be tween entrepreneurs and managers. The main objective of this research is to identify w hether certain personality traits have an influence on career aspirations. Therefore, one could assume the ambition level of students aspiring a top management positions or an entrepreneu rial firm is the same, given that a high level of career aspirations could lead to either a t op position within an organization or to starting a new entrepreneurial business. 3.5.2. Overview of the personality traits On the next page you can find the schedule of the personality traits as discusse d in the previous sections. 26 IEO Innovativeness Proactiveness/ personal initiative Risk-taking Competitive aggressiveness Autonomy Learning orientation Achievement orientation Entrepreneurial traits Internal locus of control High need for achievement Risk-taking propensity Top management traits Neurotiscism Extraversion

Openness to experience Agreeableness Conscientiousness Figure 1: Overview of the personality traits. 3.6. Conclusion This chapter discussed three personality traits constructs; the individual entre preneurial orientation, the entrepreneurial traits and the managerial traits. The personali ty traits of each of these construct was elaborated upon. Furthermore, the differences and similar ities between the ambition of top managers and entrepreneurs was discussed. Finally, an overvi ew of the personality traits constructs is given. 27 4. Model and hypotheses 4.1. Introduction After having presented the literature on career aspirations as well as the liter ature on personality traits, the model and hypotheses can be derived from the literature. This chapter will present the research model and the hypotheses of the thesis. 4.2. Model This study examines the relationship between year of study and career aspiration s, the influence of gender and the effect of several personality traits. The first mode l, as depicted in figure 1, investigates the relationship between year of study and career aspirat ions to top management level or to start an entrepreneurial business, moderated by gender. F urthermore, the relationships between the different personality models and career aspiration s will be examined. Figure 1: Research model However, before establishing this research model, the three personality trait co nstructs need to be tested separately in order to identify the most important personality factors and their Career aspirations to top management level or to start an entrepreneurial business. Year of study Gender Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation Entrepreneurial Traits Top Management Traits 28 interrelations. Hence, the personality trait models will be discussed separately before integrating them in the research model. 4.3. Hypotheses The problem statement of this thesis is: What is the effect of year of study, gen der and personality characteristics on the career aspirations to top management level or to start an entrepreneurial business? In order to find the answer to the problem statement, t he different literature bodies are discussed extensively and the concepts are elaborated upon

. However, in order to research the overall model and the separate relationships, an integrati on of the concepts is necessary. Thus, before discussing the research methodology, the con cepts will be integrated and hypotheses will be formulated. Firstly, chapter two has outlined the starting point of career aspirations and t he factors that can change the career aspirations of individuals. Following the reasoning of Dan ziger and Eden (2007), students tend to change their ideas and visions of the future durin g college, which will result in an adjustment of their career aspirations. This leads to th e following hypothesis. H1: Career aspirations of students will decrease with the years of study. Secondly, the question arises whether there will be a difference between male an d female students career aspirations. The theories discussed in chapter two originate from gender differences in career related issues. Due to many factors like stereotyping and social gender roles (Feingold, 1994; Eagly and Wood, 1999; Gupta et al., 2008) individuals are influenced during their lives, specifically their childhood years. Therefore, based on the aforementioned theories, there will be differences between genders in career aspirations. Follo wing the results of Danziger and Eden (2007), men are more likely to aspire a partnership or top position than women. Hence, the following hypotheses can be derived. H2: Male students will have higher career aspirations to top management level or to start an entrepreneurial business than female students. Furthermore, as aforementioned in chapter two, people need to compromise as they discover barriers to their preferences. This reality check often results in an adjustment of their career aspirations, since men and women seek a match with work, family and marriage responsibilities. This reality check is more radical for women, which leads to c hange of career 29 Innovativeness Personal initiative Risk-taking Competitive aggressiveness Autonomy Learning orientation Achievement orientation IEO Career aspirations to top management level or entrepreneurship H4a H4b H4c H4d H4e H4f H4g

aspirations (Whitmarsh et al., 2007), because women expect to face difficulties in combining family and work. H3: Differences between the sexes in career aspirations will increase with the n umber of years of study Additionally, chapter three elaborates on the personality traits expected to hav e an influence on career aspirations. Individuals with a higher score on certain personality tr aits are anticipated to score higher on career aspirations as well. Krauss et al. (2005) highlighted the importance of personality characteristics on performance. The first concept disc ussed in chapter three is the individual entrepreneurial orientation construct, which is depicted in the figure below. Figure 2: Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation construct; the effect of the di mensions of the IEO on career aspirations An innovative mind-set and a positive attitude towards new ideas and visions can he lp people to develop dreams of the future. If individuals enjoy having an influence on the en vironment and on other people, it seems reasonable to believe innovativeness has a positive in fluence on career aspirations to top management or entrepreneurship. H4a: The students innovativeness is positively related to career aspirations. Krauss et al. (2005) also found personal initiative to have a positive effect on business performance across all the measurement levels (i.e. individual and firm). Person al initiative/ proactiveness is a forward-looking variable and a forward-looking perspective ca n be 30 assumed to be necessary to have the aspirations to reach executive level or to s tart your own business. H4b: The students personal initiative is positively related to career aspirations . Lumpkin and Dess (1996) assume there is a relation between risk-taking and succe ss. Krauss et al. (2005) take on this assumption and argue that a positive risk-taking orie ntation helps to take on risks and challenges. To become a top executive manager or entrepreneur, people need to take on challenges and will face uncertain times. One could assume that individuals with a positive risk-taking orientation will have higher aspirations. H4c: The students risk-taking orientation is positively related to career aspirat ions. Furthermore, besides Krauss et al. (2005), competitive aggressiveness has not be en researched from an individual level. Although the results of Krauss et al. (2005) showed th at competitive aggressiveness is not part of the entrepreneurial orientation construct in all t ests, the results from the individual level demonstrate the positive influence of the dimension on business performance. Individuals with a high level of competitive aggressiveness want to

perform better than their competition and strive for victory (Krauss et al., 2005, p.320). One can assume this has a positive influence on their career aspirations. H4d: The students competitive aggressiveness is positively related to career aspirations. It seems reasonable to believe that an autonomy orientation has a positive influ ence on career aspirations. As aforementioned, managers and entrepreneurs with a high autonomy orientation are motivated to fulfill their own dreams, ideas and visions (Krauss et al., 200 5). Consequently, the autonomy orientation has a positive influence on career aspira tions. H4e: The students autonomy orientation is positively related to career aspiration s. The research by Krauss et al. (2005) investigated the relation between the indiv idual entrepreneurial orientation dimensions and business performance. Achievement ori entation, personal initiative and learning orientation all correlated significantly with b usiness performance. Learning has an influence on the behavior of entrepreneurs (Krauss et al., 2005) and because the career aspirations construct is partly behavioral, one could ass ume learning can have an influence on career aspirations. H4f: The students learning orientation is positively related to career aspiration s. One of the most important factor is achievement motivation, because if a manager or entrepreneur does not want to reach specific goals, like top management or an ow n business, they are not willing to work hard to reach those goals. According to Hambrick, F inkelstein and Mooney (2005), aspirations could be influenced by personality factors like n eed for 31 Internal locus of control High need for achievement Risk-taking propensity Career aspirations to top management level or entrepreneurship Entrepreneurial traits H5a H5b H5c achievement. Additionally, Krauss et al. (2005) found achievement orientation to be positively related to business performance. H4g: The students achievement orientation is positively related to career aspirat ions. The model as depicted below shows the relationship between the entrepreneurial t raits and career aspirations to top management level or entrepreneurship. Figure 3: Entrepreneurial traits construct; the effect of the entrepreneurial tr aits on career aspirations According to Hambrick, Finkelstein and Mooney (2005) and Miller, Kets de Vries a nd