Professional Documents

Culture Documents

City Limits Magazine, May 1995 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

City Limits Magazine, May 1995 Issue

Uploaded by

City Limits (New York)Copyright:

Available Formats

NewYork's Urban Affairs News Magazine May 1995 $3.

00

.1

City Limits

Volume XX Number 5

City Limits is published ten times per year.

monthly except bi-monthly issues in June/July

and August/September. by the City Limits Com-

munity Information Service. Inc . a non-profit

organization devoted to disseminating informa-

tion concerning neighborhood revitalization.

Editor: Andrew White

Senior Editor: Jill Kirschenbaum

Associate Editor: Kim Nauer

Contributing Editor: James Bradley

Art Director: David Huang

Advertising Representative: Faith Wiggins

Intern: Laura Clark

Proofreader: Sandy Socolar

Photographers: Steven Fish. Eve Morgenstern.

Gregory P. Mango

Sponsors:

Association for Neighborhood and

Housing Development. Inc.

Pratt Institute Center for Community

and Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of Directors':

Eddie Bautista. New York Lawyers for

the Public Interest

Beverly Cheuvront. City Harvest

Francine Justa. Neighborhood Housing Services

Errol Louis. Central Brooklyn Partnership

Mary Martinez. Montefiore Hospital

Rima McCoy. Action for Community

Empowerment

Rebecca Reich. Low Income Housing Fund

Andrew Reicher. UHAB

Tom Robbins. Journalist

Jay Small. ANHD

Walter Stafford. New York University

Doug Thretsky. former City Limits Editor

Pete Williams. National Urban League

"Affiliations for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals and

community groups. $25/0ne Year. $35/Two

Years; for businesses. foundations. banks.

government agencies and libraries. $35/0ne

Year. $50/Two Years. Low income. unemployed.

$10/0ne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article

contributions. Please include a stamped. self-

addressed envelope for return manuscripts.

Material in City Limits does not necessarily

reflect the opinion of the sponsoring organiza-

tions. Send correspondence to: City Limits.

40 Prince St.. New York. NY 10012. Postmaster:

Send address changes to City Limits. 40 Prince

St.. NYC 10012.

Second class postage paid

New York. NY 10001

City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)

(212) 925-9820

FAX (212) 966-3407

Copyright 1995. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be

reprinted without the express permission of the

publishers .

. City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from

University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor,

MI 48106.

. 2/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

Depraved Indifference

T

he rats were such frequent visitors to her second floor apartment that

Doris Ruffin even gave one a name, Herman. The day Herman

jumped onto her bed while she was snoozing is the day she decided

to stop paying the rent. By that time, she adds, it had been years

since the building's front door had a lock; since drug dealers took control

of the entryway; since tenants could rely on the landlord to provide heat or

hot water, much less a functioning elevator for the elderly folks on the up-

per floors.

Two months ago, on March 8, a judge in Housing Court gave the land-

lords until March 20 to repair the holes in the walls and floors of Ruffin's

apartment. "No one came," she says. The next day, the building collapsed.

The collapse of 142 West 140th Street in Harlem has attracted a great

deal of attention from the press and politicians. As Ruffin told her tale to

members of the City Council at a hearing recently, questioners focused on

how city inspectors could have failed to notice the structural decay of the

building on repeated visits. That is an important issue, certainly. But only

one or two of the Councilmembers seemed the least bit concerned about the

most painful information conveyed by these former tenants: ' what it was

like to live in a dark, decrepit, rat-infested slum buUding for the five or

more years it had been in decline.

The centerpiece of this issue is dedicated to understanding the private

housing market in New York City's low income neighborhoods. As you

will learn from the articles beginning on page 10, it is a predatory business.

A great deal of money has been made by financiers and speculators work-

ing the housing market in Central Harlem and similar communities. Count-

less tenants have lived-and died-with the consequences. Read on to

learn how it is done.

The city is at a turning point in housing policy. Commissioner Deborah

Wright of the Department of Housing Preservation and Development is de-

vising a new plan for dealing with tax delinquent properties, most of them

in low income neighborhoods. If her only solutions are to loosen govern-

ment regulation of landlords, challenge rent stabilization laws and lobby

for Housing Court "reform" that favors owners, she will solve nothing. The

city must devise a policy that uses whatever leverage it has at its disposal-

tax foreclosure, code enforcement, court appointed administrators-to en-

sure that landlords and their mortgage holders maintain property in decent

condition. Only then should discussions focus on reducing the cost of

ownership, not through deregulation but, perhaps, with targeted tax abate-

ments and low interest rehabilitation loans that do not undermine afford-

ability for the tenants.

If landlords cannot manage their properties, the city should take them in

tax foreclosure or otherwise eliminate the mortgage debt held by private fi-

nanciers and then transfer ownership cheaply and quickly to tenants or a

community group. There is no reason the city has to hold onto tax fore-

closed property for decades at a time, as it does today. If City Hall devoted

adequate resources to tenant and community organizing. clarified its hous-

ing sales programs and maintained a high level of rehabilitation funding,

the process could move much more speedily.

-A.W.

In an article last month about the city's Neighborhood Entrepreneurs

Program, we incorrectly identified a bank whose charitable foundation has

provided a grant to the New York City Housing Partnership to work with

landlords and tenants. Its correct name is the Industrial Bank of Japan.

Cover illustration by David Chelsea

SPECIAl.. REPORT:

PROFITS FROM POVERTY

The Big Squeeze 10

Everybody's talkin' 'bout regulation, high taxation, litigation. Devas-

tation. But no one wants to face up to what's really controlling the

cost of private low income housing: the market. by Andrew White

Making Millions Out of Misery 14

The landlords of a collapsed building in Harlem are facing bankrupt-

cy, foreclosure and criminal charges. But for the fmancial operators

behind the scenes it's simply business as usual. Getting away clean,

making a killing. by Kim Nauer, Andrew White and Jesse Drucker

Code Enforcement Conundrum 19

In Housing Court, city attorneys routinely give landlords with rap

sheets as long as Pinnochio's nose the chance to make "good faith"

efforts at repairs, no money down. by Jill Kirschenbaum

FEATURE

A Woman's Work 22

Job training programs designed to meet the special needs of women

overcoming poverty are succeeding where previous efforts haven't-

moving them off welfare and into independence. by Seema Nayyar

PROFII..E

Wise Man 6

At 50, Richie Perez is New York's grand old man of Puerto Rican

activism. by Stuart Miller

WORKING ASSET

Harmonic Convergence 26

Long before the city started to rethink its development policy for

homeless people with AIDS, the creators of Flemister House were

piecing together a strategy of their own. by Stephen ArrendeU

COMMENTARY

Cityview

Ransomed Justice

Review

Where You Hang Your Hat

DEPARTMENTS

Editorial

Briefs

More Cuts to Kids

Incinerator Rebound

CRA Regs, Finally

Loan Fund Slashed

by Angelita Anderson

by Robin Michaelson

Clearinghonse 29

2

Letters 34

4

Professional Directory 38

4

5

lob Ads 37,38,39

5

10

6

22

CITY LIMITS/MAY 1995/3

BRIEFS

More Cuts

to Kids

Anti-prostitution

budget axed

Another funding stream feed-

ing an ever-dwindling pool of

city moneys for youth services in

New York is drying up, this one

for three programs that serve the

most vulnerable of New York's

homeless population.

Tagged by the city Child Wel-

fare Agency (CWA) as prevention

and" Juvenile Prostitution Diver-

sion" funds, the $920,000 pool of

money is slated to disappear

July 1. And while it represents

only a tiny fraction of the mas-

sive CWA budget, for the kids

who rely on the services and

support of Streetwork, the Het-

rick Martin Institute and The

Door, the impact of the cut will

be substantial

"We're really worried," says

Angela Amel, clinical director of

Streetwork, which offers counsel-

ing, outreach and a drop-in cen-

ter for homeless and runaway

youths in the limes Square area

of Manhattan. "It's going to be

devastating for the kids."

Streetwork, a project of the

Victim Services Agency, is losing

$390,000 of its annual operating

budget of $1 .2 million. As a re-

sult of the cut, Streetwork is

scrambling to find other funders

to make up the difference. But in

the meantime they are making

some hard choices about the ser-

vices they can offer.

"We are seeing sixty to ninety

kids a day at our drop-in center,"

says Amel, a significant number

of whom are engaged in prostitu-

tion, drug sales and other risky be-

havior associated with street life,

she says. Many are AWOL from

the foster care system, some have

mental health problems and all

are at risk of assault on the street.

Many, too, are HIV positive.

"These are kids who live on

the street, who are dirty, who are

completely marginalized," says

Francis Kunreuther, director of

the Hetrick Martin Institute.

Opened in 1987, Hetrick Martin

started out working primarily

4/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

with boys involved in prostitu-

tion at the piers on the West

Side, but has grown into a $2.6

million operation that now also

sees a lot of kids who gravitate

to the East Village. Many start

out panhandling but move into

prostitution when survival on

the street becomes threatened,

Kunreuther explains. "These are

not the poster children," she

says, "but they are the kids most

in need."

Like Streetwork, Hetrick Mar-

tin is perhaps the only link its

clients have to essential ser-

vices such as health care, food

and shelter. The organization is

losing its contract for $170,000.

CWA's prevention moneys

were first made available in

1984 by then-Mayor Ed Koch af-

ter a report was released expos-

ing the extent of juvenile prosti-

tution in New York City. Karen

Calhoun, spokesperson for

CWA, says that because of the

many cutbacks the agency has

endured in recent budget

rounds, "We've had to decide to

only provide our core mandate

of preventive services to chil-

dren under eighteen, those who

are at risk of imminent foster

care placement or have been

discharged and are at risk of go-

ing back to foster care."

But the needs of kids on the

street, many of whom are fleeing

abusive foster care placements,

has hardly diminished, says

Katey Assem, executive director

of The Door, a multiservJce cen-

ter that serves a wide range of

New York City youth. Its prostitu-

tion diversion and other preven-

tion services include counseling,

job training, apprenticeships and

placements as well as health

care and family planning. They

are losing $360,000 of an annual

budget of $7 million.

"Cuts to this program won't

break our budget," says Assem.

"But these young people, who

are otherwise prostituting them-

selves on West 12th Street and

42nd Street, here they had a di-

version, someth ing that gave

them the skills and the empow-

erment to get involved in posi-

tive activities. This puts them

right back on the street. Putting

more cops out there is not going

to solve this problem."

Jill Kirschenbaum

Incinerato.r Rebound

A few weeks ago, environmental justice

activists thought they might soon hammer

the last nails into the coffin of a fiscally bank-

rupt four-year-old medical waste incinerator

in the South Bronx. But then the nation's sec-

ond-largest waste disposal company stepped

into the picture.

Early last month, Browning-Ferris Indus-

tries won a bankruptcy court judge's approval

to purchase the Bronx-Lebanon incinerator in Port Morris for '

$4.5 million. If it goes ahead, the deal would be a coup for the

Texas-based company: originally, the incinerator was developed

at a cost of more than $15 million, much of it provided through

government subsidized city industrial development bonds.

The bankrupt owners of the incinerator, Metro New York

Health Waste Processing, have committed repeated emissions vi-

olations. Browning-Ferris promises to run the incinerator cleanly

and in full compliance with its state environmental permits.

But members of The South Bronx Clean Air Coalition say

that's not good enough. They want the plant shut down for

good, and they are organizing local residents to pressure Brown-

ing-Ferris not to go through with the purchase.

Unfortunately the bankruptcy court has opened this up to a

larger organization that knows how to manipulate situations a

lot more effectively, says Frances Sturim of the Riverdale Com-

mittee for Clean Air, which is working with the South Bronx

group. We don't want Browning-Ferris in the Bronx. We will

continue to put pressure on them and we hope they see the

light. Andrew White

... --------

,

I

I

I

I

I GUTSY. INCISIVE.

I PROVOCATIVE.

I

I

I

I

City Limits shows you what is working in our

communities: where the real successes are

taking place, :wbQ is behind them, wM they're

working and we can all learn from them.

And we expose the bureaucratic garbage,

sloppy supervision and pure corruption that's

failing our communities. City Limits: News.

Analysis. Investigative reports. Isn't it time

you subscribed?

I YES I Start my subscription to City Limits.

Q $25/one year (10 issues)

Q $35/two years

Business/Government/lJbraries

Q $35/one year Q $50 two years

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

Address

City State Zip I

I CityLimits, 40 Prince Street, New York 10012 I

... _------_ ...

eRA Regs,

Finally

It's official. After two years of

intense negotiations with com-

munity activists and banks, gov-

ernment regulators have released

new rules governing the nation's

Community Reinvestment Act

(CRA). Their publication on April

19 in the Federal Register caps

two rounds of often heated con-

troversy over how much banks

should be required to invest in

disadvantaged communities.

"[Neighborhood groups)

weren't happy with some aspects

of it, but everything considered,

they thought these were regula-

tions they could live with. And the

industry response was pretty

much along the same lines, " says

Allen Fishbein, general counsel

for the Washington-based Center

for Community Change. "Now

we think they ought to be given

an opportunity to be tried."

But they may not be, thanks

to several legislative efforts to

gut the act now underway in the

Republican-controlled House

and Senate. The most serious of

the bill s now in committee

would exempt more than 95 per-

cent of the nation's banks from

activist CRA challenges. Senate

hearings begin in mid-May.

"That's the opening shot," Fish-

bein says.

Assuming CRA remains in-

tact, here are some highlights in

the new regulations:

Banks will now be evaluated

according to the adequacy of their

branch services, their community

investments and the amount of

lending they do in the neighbor-

hoods where their depositors live.

Lending is considered para-

mount: a bank cannot pass its

CRA examination without getting

a satisfactory lending rating.

Examiners will also use

comparative lending tests. They

will assess a bank's lending

record by comparing it with oth-

ers serving the same communi-

ty. The public will also be notified

of upcoming CRA evaluations, a

provision that could give local

groups more of an opportunity

to participate in the process

Banks will have to report

the number of business loans

they have made in a given cen-

sus tract. They will also have to

report how many business loans

they have made by income

group .

A controversial proposal re-

quiring that banks report the race

and gender of their small busi-

ness loan recipients was dropped

from the final rules. While

bankers wanted to steer clear of

the extra paperwork involved,

they also argued that collecting

such information could be viewed

as a violation of the Equal Credit

Opportunity Act, which outlaws

racial discrimination in lending.

To overcome this complaint, Fish-

bein says, regulators have pro-

posed a change to the ECOA rules

allowing banks to collect and

publish this data, if they wish.

Regulators are now seeking com-

ment on this proposal.

"If you assume the new regu-

lation does get adopted for the

race and gender reporting, there

will be many of the elements that

community groups wanted to

see in terms of more information

about small business lending ac-

tivity," he says. "Perhaps it's not

as systematically laid out as peo-

ple would like, but there will be

some important pieces of infor-

mation available."

The next step, assuming

Congress doesn't gut the law, is

to help regulators write a de-

tailed CRA evaluation manual

for their staff. Activists have

also been invited to help with

training and recruitment.

The new regulations still

leave a great deal up to the judg-

ment of individual bank examin-

ers, Fishbein says. "Now they'll

have more data, but they need to

Loan Fund Slashed

A cornerstone of President

Clinton's urban investment ini-

tiative is in trouble and likely to

lose much of its current funding

under the Republican-controlled

Congress.

The much-touted community

development financial institution

(CDFI) loan fund had been allo-

cated $125 million for the current

year. Altogether, the four-year

program was slated to receive

$382 million for distribution

among the nation's tiny commu-

nity-based banks and credit

unions. However, the House, in

a recent funding rescission bill,

decided to withhold all but $1

million of this year's allocation.

Thanks to some last-minute

lobbying by grassroots forces,

the Senate restored $36 million

for the current year.

Now the two proposals are

scheduled for debate in confer-

ence committee. Word on the

street is that the House will al-

low the $36 million allocation

with, perhaps, some new

strings attached.

"The good news is that the

program is going to survive. The

bad news is that it was scaled so

far back: says Mark Pinsky, ex-

ecutive director of the National

Association of Community De-

velopment Funds.

Adding insult to injury, the

BRIEFS

learn how to apply it in a way

that makes for a good rating sys-

tem," he adds. "That's what it's

really come down to, and we're

going to find out if they're up to

the job." Kim Nauer

Senate Banking Committee has

refused to consider the confir-

mation of Kirsten Moy, Presi-

dent Clinton's nominee to run

the loan fund. The appointment

has been sitting in the commit-

tee's in-basket since February,

Pinsky says.

He maintains that the only

long-term hope for this legisla-

tion is pressure from activists

and the communities who will

benefit from it. "This is a pretty

low-profile program when you

consider there's $60 billion ba-

ing cut from the federal budget:

he says. "But we're playing to

our strength-the only strength

we have at all-the 300-plus

grassroots member organiza-

tions we have around the Unit-

ed States. Kim Nauer

CITY LIMITS/MAY 1995/5

By Stuart Miller

Wise Man

As police brutality rates soar, Richie Perez is organizing activists

young and old for Puerto Rican rights.

M

any adults look back on

their youth and recall a

teacher who was a sin-

gular influence, a guid-

ing force during their formative

years. For Vicente "Panama" Alba,

who came of age in the Bronx dur-

ing the late 1960s, it was a high

school teacher named Richie Perez.

Following Perez's example, Alba

joined the Young Lords (a smaller

scale Latino version of the Black

Panthers) and embarked on a career

in community activism.

When Alba, now National Con-

gress for Puerto Rican Rights chap-

ter chairman for New York, took the

microphone at One Police Plaza on

March 30 and looked out on hun-

dreds of protesters marching against

police brutality, he was keenly

aware of Perez's impact, not just on

his own life, but on the entire Latino

community.

with Perez for five years dur-

ing their Young Lords days.

"He's someone you want to

get to know," says Guzman.

"He has a sense of humor

that is sorely lacking in this

line of work."

"He has transcended time

and the political element in

a way very few have," agrees

Juan Figueroa, president of

the Puerto Rican Legal De-

fense and Education Fund

(PRLDEF). "He was effective

in 1975 and he is effective

in 1995."

Intent and Outspoken

Perez is not some spectral pres-

ence, an Obi Wan Kanobi of the

grassroots movement. After nearly 30

years of activism he remains on the

front lines. The National Congress'

national coordinator, Perez is the

man who handed Alba the micro-

phone. Now 50, he is both elder

statesman and dynamic leader.

After neart, 30 ,ears of activism, Richie Perez of the National

Congress for Puerto Rican Rights remains on the front lines.

Sitting in his sunny East

22nd Street office at the

Community Service Society,

where he runs the Depart-

ment for Political Develop-

ment, Perez, a short, solidly

built man with a salt-and-

pepper beard, exudes a pro-

fessorial air. He is intense

and outspoken, but his

thoughts are well organized,

and he occasionally refers to

notes on a yellow pad.

Raised in the South

Bronx, Perez was the first in

The demonstrators were protest-

ing what they considered to be too-le-

nient charges filed by the Bronx Dis-

trict Attorney against police officer

Francis Livoti in the December death

of Anthony Baez. The University

Heights incident occurred after Baez's

football struck Livoti's police car. The

officer allegedly used an illegal choke

hold, which Baez's three brothers wit-

nessed. Livoti has pleaded not guilty to

a charge of criminally negligent homi-

cide which could lead to a maximum

of four years in prison.

On one level, the demonstration

might be considered a failure, receiving

scant media attention for its demands

for a jury trial, an independent prose-

cutor and a federal investigation into

the rapid rise of brutality cases under

the watch of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani.

But Sonjia Gonzalez, 25, who helped

organize the rally, says that even

6/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

though the lack of coverage was frus-

trating, "Everybody felt really ener-

gized afterward. There was a special

kinship."

There were also some tangible results:

the Congress recruited 400 participants

to fill the courtroom during Livoti's trial

in order to counter the anticipated po-

lice union presence.

The ability to make the most of a sit-

uation is just one reason observers

rank the tenacious Perez among the

Latino community's most prominent

grassroots activists. "He is truly the

most committed person I have met,"

says Newsday reporter Elaine Rivera,

who has interviewed Perez on every-

thing from police brutality to school

board elections.

His gift of leadership is rooted in an

infectious personality, adds NBC news-

caster Pablo Guzman, who roomed

his family to go to college. At

Lehman College, he cared more about

"hangin' out" than politics, he recalls.

It wasn't until he became a stenogra-

phy and civics teacher at James Mon-

roe High School in the late 1960s-he

opposed the Vietnam War, and inner-

city teachers were given draft defer-

ments-that he says he gradually be-

came "deeply politicized."

He chipped in with an English

teacher to buy copies of Down These

Mean Streets, Piri Thomas' seminal au-

tobiography about growing up in the

Puerto Rican ghetto, which soon be-

came a status symbol among students.

When Perez' colleague was nearly fired

for going outside the approved reading

list, "It became clear the bureaucracy

was about control and uniformity, not

about reaching the kids," he says. He

quickly realized the importance of or-

ganizing. "When you're dealing with a

tremendous institutional bureaucracy,

individuals cannot change things. Only

groups of people who coalesce can."

In 1969 the Young Lords were born

and Perez discovered a group of kin-

dred radical spirits. A year later he left

teaching to become a community orga-

nizer, a role he retained even after he

returned to teaching in 1972. "People

really rallied around him," Guzman re-

calls. "Students were devoted to the

guy." But the Lords had little guidance

from previous generations and were

soon tom apart by dogmatic battles and

power grabs.

Perez rebounded in the 1980s, start-

ing with a nationwide protest against

the Paul Newman film, Fort Apache,

The Bronx, that attempted to educate

the Latino communi-

ty about the long last-

ing impact of nega-

tive media images.

Perez, Alba, and Juan

Gonzalez (now a Dai-

ly News columnist)

were among those

who molded a loose

network of activists

into the National

Congress, hoping to

supply a grassroots

voice for their com-

munity's most vul-

nerable citizens.

goes to those who devote the time.

Political Growth

In 1983, Perez was hired by the

Community Service Society to run a

voter registration pilot project in Bush-

wick. In two years, the assembly dis-

trict's turnout jumped from 4,000 to

6,000. "We destabilized the status

quo," Perez says. The program served

as a model for other neighborhoods

and a symbol for Perez's own political

growth. He had grasped the impor-

tance of electoral power, seeing both

the obvious-votes bring quality-of-life

results like getting streets paved-and

the subtle-registration campaigns

help build a mailing list and a base for

other forms of struggle.

ing policies and forced the public televi-

sion station to make annual reports on

hiring to the FCC instead of once every

five years. In 1990, the Congress was

part of a coalition that successfully bat-

tled a City Council redistricting plan

that they charged discriminated against

Latinos. The group is also a key player in

the ongoing fight against a medical

waste incinerator in the South Bronx.

Today, racial and police violence

are the group's core interests. Crisis

teams reach out to families in the first

hours after a racial incident; others ad-

vise on challenging a bewildering bu-

reaucracy. The Congress even pub-

lished a newspaper-Justice Daily-

during one case, Perez says, providing

lawyers and observers "serious scruti-

ny" of the proceed-

ings.

Many of them had

a clear memory of the

bitter infighting that

wrecked the Young

Lords, so the Con-

gress sought to de-

velop along pragmat-

ic rather than ideo-

logical lines. Alba

Protestors head into the streets near City Hall following a March lOth demonstration against

police brutality.

To build support in

New York's Puerto

Rican community,

where the median age

is about 22, Perez says

the organization has

offered advice, con-

tacts and endorse-

ments to a large num-

ber of youth-spon-

sored community pro-

jects-including re-

cent efforts by gangs

such as Strictly Ghet-

to, Zulu Nation and

the Latin Kings to be-

come involved in po-

litical organizing. The

effort is appreciated.

"I don't know of an-

other organization in

New York that reach-

says their inclusive approach "recog-

nized you didn't have to be a revolu-

tionary to be a tenant organizer." They

also specified that half the leadership

positions were to be filled by women.

And after studying established organi-

zations, the Congress decided not to

seek any government or corporate

funding so they wouldn't have to wor-

ry about criticizing someone with con-

trol over their purse strings.

"It makes you fiercely independent,

but on the other hand you're totally

poor," Perez says. "It's slow going. The

political goals are not matched by an

economic infrastructure." On the bright

side, says Priscila Curet, the Congress

executive board's Philadelphia repre-

sentative, there are few internal clashes.

In an all-volunteer organization, power

The National Congress now has

about 4,000 members, including affili-

ated organizations, though Perez ac-

knowledges the core group is much

smaller. The leadership's radical past

attracts young members like Sonjia

Gonzalez and Pete Diaz, both of whom

were inspired by hearing Perez speak

about the Young Lords at school forums

and community meetings. "His long

struggle counts with us," says Diaz, 25.

The Congress has become a key play-

er in shaping Puerto Rican advocacy na-

tionwide, adds PRLDEF's Figueroa; over

the years, its staple issues have been

racial violence, language rights, environ-

mental justice and police brutality. As

part of a media discrimination campaign

several years ago, the Congress took

WNET to task for its poor minority bir-

es out to young peo-

ple like them," says Diaz. Two years

ago, the Congress even gave its bless-

ing to a new Young Lords group in East

Harlem, even as Perez warned partici-

pants it was likely to fail. "They fol-

lowed the paramilitary structure.

There was not enough democracy," he

says. "But they had to go through it

themselves. And we still work with

most of those kids."

Following a CUNY students' rally at

City Hall that disintegrated into rioting

and arrests, Perez strove to keep order

at the Police Plaza protest. Novices

were taught what to carry (tokens,

identification, no weapons), what to

wear and what to do if they were ar-

rested. Between the chants of "No jus-

tice, No peace!" and other impassioned

declarations, Perez repeatedly urged

CITY LIMITS/MAY 1995/7

protesters to follow the rules and main-

tain discipline. When they headed to-

ward City Hall, people lined up by

group: first came the families of brutal-

ity victims, followed by clergy, guests

such as former Black Panthers and

members of the Committee Against

Anti-Asian Violence, then youth groups

like El Puente. There was a surge of

emotion and an increase in volume as

the marching began, but no breakdown

in discipline, and no arrests.

Charismatic Leaders

Perez and the Congress do have critics

in the local Puerto Rican activist com-

munity. Observers both inside and out-

side the group believe the Congress has

failed to reach its potential, especially in

mobilizing more of the population.

Part of the problem is that too much

responsibility falls on the group's

charismatic leaders, says Eddie

Bautista, who was the Congress' New

York City chairperson in 1991 and 1992.

"Richie and Panama are keeping the or-

ganization alive. They are not being giv-

en enough support," he says. That has

led to a gap in which regular meetings

required by the Congress bylaws often

fall by the wayside. So in spite of a

"kick-ass mailing list," Bautista says it

is sometimes unclear who the group's

actual members are and whether they

are fulfilling their responsibilities.

"They need work plans. It's too ad

hoc, too reactive," he says, adding that

what Perez calls the natural ebb and

flow of activist participation could be

avoided with more proactive strategies.

Perez doesn't entirely disagree.

"Volunteer organizations are notori-

ously problematic, since you can't

make anybody do anything." Indeed,

the group recently dissolved its board

and plans to refine its structure at its

next convention.

Meanwhile, the group continues to

push itself into new territory. When

two gay members left for college, Perez

asked gay organizations to educate his

members on the issues. The Congress

has since lent support to battling ho-

mophobia in the Latino community

and the city. Perez pursued this despite

internal resistance from those who pre-

fer to focus on exclUSively Puerto Ri-

can issues because he believes survival

depends on evolution.

Evolution even includes going on-

line: BoricuaNet, a nationwide Internet

communication service for Puerto Ri-

can activists tied to San Francisco's

PeaceNet system, will "help us pro-

mote computer technology among

people, and we can have on-line

conferences overnight when something

happens," Perez says.

Still, of all the tricks in his bag, di-

rect action remains the most crucial.

"You don't get attention until you dis-

play your ability to throw a monkey

wrench into business-as-usual," he

says. With more than 40 Bronx police

officers under official investigation for

alleged brutality and other abuses,

Perez says the situation has "reached

the point of immorality" under the

Giuliani administration. He is prepar-

ing to challenge the Mayor with a civil

disobedience campaign.

While such a move may guarantee

more media coverage, conventional

wisdom says that the Mayor responds

poorly-and with stiffresolve-to such

confrontational tactics.

Nontheless, Perez thrives on "this

David and Goliath stuff." He has no in-

tention of backing down. And after a

quarter-century of uphill battles, he re-

mains an optimist. "As long as I ad-

vance the starting point for the next ef-

fort, then that's a victory." D

Stuart Miller is a Manhattan-based

freelance writer.

Applications Sought for Seventh

leadership New York Program

Leadership New York is a competitive fellowship program co-sponsored by the New York City Partnership and Coro. In

the nine-month program, during which participants are expected to remain employed full-time in their current profes-

sions, participants explore the critical issues confronting New York City.

These include housing policy, the city's educational, social service, health care and criminal justice systems, infrastruc-

ture, and the city's changing demographics and power structures.

Leadership New York welcomes applications, which must be accompanied by two letters of recommendation, from the

public, private and non-profit sectors. Candidates should have a demonstrated concern about New York City, a record of

professional achievement, and the potential to playa significant role in the city's future.

For further information and applications, please telephone the program's sponsors:

At Coro: Carol Hoffman, Manager, Leadership New Yorie, 12121 248-2935

At the New Yorie City Partnership: Eve Levy, Director of Leadership Development Programs, 12121493-7505

Application deadline: June 9, 1995

a/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT IS HELPING

THESE ASSETS REACH MATURITY.

A conununity's most precious assets

are not found in its real estate or

bank accounts. They are found in

the families and businesses that

form the foundation for the future.

At EAB, we believe we have a

responsibility to create greater

opportunities for people in

New York conununities. It is a

commitment we take very seriously.

Our Neighborhood Mortgage

Program makes millions of dollars

available to low and moderate

income horne buyers. These

individuals benefit from flexible

1995 EAB

underwriting, no points and down

payments as low as 5% (with as little

as 3% of their own money).

Through Cash Reserve Credit

Lines (Overdraft Accounts), EAB is

helping people establish a credit

history. We're also using our personal

and horne-secured loans to help

families finance educations, horne

improvements and make other

important purchases.

Anything worth building takes

time. That is why EAB is committed

to conununity revitalization over

the long term. The true beneficiaries

will be future generations. Those

given an opportunity to realize their

dreams. That is what any good

investment is all about. To learn

more about EAB's commitment

to conununity reinvestment, call

1-800-EAB-5354.

Full Service Banking

Member FDIC Equal Opportunity Lender

CITY LIMITS/MAY 1995/9

I

na windowless midtown confer-

ence hall, dozens of civic-minded

denizens of the City Club sat over

lunch last month, listening to

experts discuss the high cost of

building and operating rental

housing. The panelists sitting

beneath the white blast of televi-

sion lights included the city's

housing commissioner, a major

developer, a representative of a

landlords' trade association and a

nonprofit housing advocate.

They talked about excessive

taxes. They talked about the high

costs of regulation and complicat-

ed building codes. They talked

about landlord/tenant court.

Clearly, the conventional

wisdom has it that New York's

housing problems are entirely the

result of the depredations of

regulatory socialism.

"We can't have housing in New

York without subsidies," said Dan

Margulies of the Community

Housing Improvement Program,

an owners' trade association.

"Why? Because the government

has its hands in the pocket of

every landlord in the city."

Not once during more than an

hour of discussion, however, did

anyone in the room mention the

single largest element that

controls the order of the universe

for private, low income housing:

The market.

By

lO/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

Speculation,

poverty,

disappearing

subsidies.

Has debt

killed the

private inner-

city housing

market?

A

s the articles in this City Umlts Special Report make indIs-

putably clear, there are some fundamental reasons why the

city's market for affordable housing is severely out of kilter.

Foremost among them: excessive debt financing, reckless

landlord speculation, irresponsible lending-and of course

urban poverty. We are currently riding out the aftershocks

of wild, late 1980s real estate speculation, not only in up-

scale districts but throughout the city's low income neigh-

borhoods.

It all began in the early part of the last decade when, after

20 years of devastating owner-abandonment and arson-for-

profit, government returned to neglected areas with low-in-

terest financing, replacing windows and boilers, eventually

even financing the rehabilitation of entire buildings. Within

five years, this public investment helped put a stop to the

long decline, recalls former city housing commissioner

Felice Michetti. But it also sparked private investment,

much of it extremely reckless, as speculators got caught up

in the highs of a co-op conversion frenzy they thought

would spread from gentrifying middle class areas.

"Private capital became available in a way that wasn't

responsible, that didn't recognize a building's value in its

operating costs and its bottom line," says Michetti. In other

words, people were buying apartment buildings on the

assumption that they could get rid of their poor tenants and

jack up the rent, convert to a co-op, or just ride the market

and sell again. "Buildings became over-mortgaged, leading

to economic abandonment," she continues. "Instead of

burning the building for insurance proceeds, owners

basically cashed out through over-mortgaging. Now what

you have is physical abandonment again, as a result of

economic abandonment."

Here are the results: Today, there are about 1,400 mid-size

and large apartment buildings at least three years behind on

their city taxes, almost five times as many as in 1990. Near-

ly all of them are in the city's lowest income neighborhoods,

according to research data produced by Vic Bach of the

Community Service Society, and they contain as many as

20,000 apartments. Meanwhile, mortgage foreclosure rates

have been soaring for half a decade. And late-1980s debt-fi-

nancing shenanigans that led to the federal government

takeover of small local banks-Ensign and Freedom Nation-

al among them-are only now being ironed out. Meanwhile,

the properties they financed are returning to the market of-

ten in far worse condition than they were when the cycle of

speculation and foreclosure began.

Through all of this, it is the tenants who have taken the

hardest hit. On March 21, part of a building collapsed on

West 140th Street in Central Harlem. While engineering ex-

perts say the immediate cause was water damage to a lime-

stone foundation, tenants say signs of instability were obvi-

ous for months and neither the owners nor the superinten-

dent paid attention. The tale behind that decline unfolds in

the article beginning on page 14. The owners had been in

and out of bankruptcy; they were five years behind on their

taxes and on a $10.3 million mortgage that included a dozen

other buildings. All were in deteriorating condition.

"The mistake would be if this were seen as some kind of

isolated incident," says Andy Scherer, coordinating attor-

ney with Legal Services of New York. "It can't be seen as a

building slipping through the cracks. The cracks are so big,

many buildings are destined to slip through."

"It takes this kind of thing to make the front page," adds

a housing activist who works for a large charity and asked

not to be quoted by name. "Yet no one admits this is going

on all the time. Kids are bitten by rats all the time, sewage

seeps into children's bedrooms all the time, people fall

through the floors all the time. It's a day-in and day-out con-

dition for many people in these neighborhoods. Yet that

never makes the cover of The New York Times."

T

he city is at a critical turning point in its housing policy. For 20

yean, up until late 1993, the city had a policy of taldng title, or

"vesting," any property whose owners had fallen at least

one to three years behind on their property taxes. That era

appears to be permanently over. The city currently owns

tax-foreclosed buildings containing about 42,000 apart-

ments. At the behest of the Giuliani administration, the

Arthur Andersen consulting firm recently completed a re-

port for HPD on the long-term cost of managing, rehabilitat-

ing and selling this property. Its primary finding, says HPD

Commissioner Deborah Wright, is that the long-term cost of

vesting more tax delinquent properties is far too high to jus-

tify (see sidebar, page 13).

"The question is, what should we do instead?" asks

Wright.

For the small property owners making waves at public

meetings like the City Club luncheon, or at recent City

Council hearings on Housing Court, the solution would be

for government to entirely remove itself from the market.

Deregulate rents. Cut taxes. Reform the landlord/tenant

court. In other words, cut the cost of owning housing.

None of these proposals deal with the awesome burden

that reckless speculation has laid across the shoulders of the

city's neighborhoods, however. Advocates of affordable

housing say any solution has to take into account the poten-

tial for abusing the market and the lessons of disinvestment.

"If you are going to do the Reaganomics equivalent of

supporting speculation, believing that that is an adequate

substitute for real responsible economic activity, it's going to

be disastrous," says Brien O'Toole, former director of the

Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, which

has organized tenants for more than 20 years.

Meanwhile, the number of buildings eligible for vesting

continues to rise. "It's more than doubled over the last two

years," says Bach. "These are buildings in a kind of limbo,

for which owners may no longer be doing even minimal

management.. .. The number of buildings technically still on

the private market but virtually unattended is growing by

leaps and bounds."

W

hat would a government policy look like if it took poor com-

munities and the brutal nature of the market into account?

Traditional bank financing is hard to come by in low in-

come neighborhoods. The alternative is to go to indepen-

dent mortgage financiers, who charge premium interest

rates-as much as five percentage points or more above pre-

vailing bank rates plus high broker's fees. While banks are

currently charging rates in the 8.7 percent range, these in-

dependent brokers get as high as 13 percent, according to

real estate professionals.

Meanwhile, rents must remain very low. "The tenants' in-

comes are fundamentally the problem," says Frank Braconi,

executive director of the Citizens Housing and Planning

Council. Just do the math: according to the Rent Guidelines

CITY LIMITS/MAY 1995/11

Board, the cost of maintaining and

operating the average apartment

building in the city comes to about

$382 per apartment, per month. This

does not include any debt payments

on a mortgage. If a tenant household

is going to pay only 30 percent of its

income in rent-a standard formula

used in the business-then they

must have an annual income of at

least $15,000.

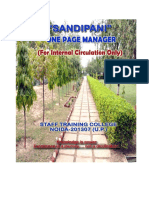

More Apartment Buildings in Serious Tax Arrears

But the median household income

in Central Harlem is only $8,500. It's

even less in parts of the Bronx.

4500

4000

3500

3000

2500

2000

1500

1000

500

o

1990 1992 1994

II

II

More than

3 years

More than

1-1/4 years

Source: Community S8Mce Society

Housing Policy and Research

Yet these are the very neighbor-

hoods where mortgages are obtained

at higher interest rates from indepen-

dent brokers. Experts say there is no

way to regulate these financiers, who

hold mortgages on a high percentage

of private apartment buildings in low

income communities. As long as peo-

ple are willing to borrow money at ex-

orbitant rates, these firms can lend it.

All they need is a broker's license,

says O'Toole, and that requires only

that one be of "good character."

Ch.rt sh_s the number of buildings with five .... rtments or more that .re eligible to be taken into

tax foreclosure by the city. As the numbers rise rapidly, 1,384 of these buildings owe more th.n

three ye.rs in back taxes-and no one knows what condition they .re in.

There are more rational and re-

sponsible ways of raising capital for housing, says Mike

Lappin of the Community Preservation Corporation (CPC),

which oversees a far more tightly regulated stream of gov-

ernment and bank financing for owners in these commu-

nities. For example, the city's Participation Loan Program

provides private owners with 30-year, low-interest mort-

gages combined with market-rate bank loans, all for acqui-

sition and rehabilitation of a property; the package is then

very closely overseen by CPC.

"When we go into a project, we want to do all of the

major renovations needed to give the building mechanical

integrity for the next thirty or forty years," says Lappin.

"That means replacing the plumbing, wiring, heating,

whatever. Then we structure the financing so the invest-

ment is feasible and the rents are affordable." In other

words, it is important to assess the long-term operating

expenses and get a clear sense of the income before fi -

nancing a building-something that frequently didn't

happen during the 1 980s when buyers had stars in their

eyes and financiers were looking for a quick deal. "To pre-

vent speculation, we will not permit sale of these build-

ings without our prior consent," adds Lappin. "If there is

additional debt on the building, we would make sure it

wouldn't be so much as debt to affect the proper operating

of the building."

Problem is, the city has only about $34 million a year to

put into this loan program. Braconi and other observers

say that amount is slowly dwindling along with the rest of

the city's budget. Even more critical, says Lappin, is the

need for rent subsidies to make many of these projects

work. A loan from CPC generally means rents are in-

creased. The larger the loan and the higher its interest rate,

the larger the rent increase.

And for the lowest income tenants, that can prove to

be no solution at all if there aren't serious long-term sub-

sidies, says Jay Small of the Association for Neighbor-

12/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

hood and Housing Development: "It means compromis-

ing tenant protections and getting someone new in who

can pay the rent."

G

overnment money to help poor people pay their rent is paltry.

The part of weHare benefits that goes to pay for housing is set

at $312 for a family of four. It's $278 for a family of three.

"It doesn't even cover the maintenance and operating

costs of the building, let alone debt service," says Marc

Jahr of LISC, which arranges financing for nonprofit hous-

ing development. "Let alone the tax bill. Let alone return.

That's the problem."

Welfare funding is under attack at City Hall, in Albany

and Washington. Federal Section 8 rent subsidies, which

provide low income tenants with vouchers covering part

of their rent on the private market, were cut by $2.4 bil-

lion in Congress last month. Next year, Washington ob-

servers say, Section 8 is very likely to take a crushing hit.

At the same time, Governor Pataki is pushing a provision

in his budget bill that would eliminate the so-called

"Jiggetts" rent supplement, a court-ordered program that

provides welfare recipients facing eviction with up to

$250 more in rent money each month. And Mayor Giu-

liani is seeking to phase out Home Relief, the welfare pro-

gram that provides a minimal income, including rent, to

indigent adults.

"They are moving so fast but they have no solution.

Just shut it down and then we'll worry about it," says

Doug Moritz, a founder of the Los Sures community or-

ganization in Brooklyn who is now an executive vice

president of the Washington Mortgage Financial Group in

Northern Virginia. "No one has come up with an alterna-

tive to public assistance for providing safe affordable

housing to low income people," he adds. "There is no

private sector alternative."

T

he crisis comes full circle, back to the Plaintive wail of landlord

organizations begging for lower taxes, less regulation, less

government. There are some changes along these lines

that affordable housing advocates support, such as private

sector demands that steeply-rising water and sewer

charges be rolled back. The city spends billions of dollars

a year maintaining its water and sewage treatment sys-

tems under federal guidelines, and the cost has been

passed on through water bills which are as much as six

times higher than they were just seven years ago.

Others say the city should overhaul the way it assesses

property values for tax purposes in low income neighbor-

hoods. "Base the assessment on the net income the build-

ing is generating, and you wouldn't owe taxes, or not

much," says Jim Buckley of the University Neighborhood

Housing Program in the Bronx. "Get people to open up

their books. Some buildings, they have absolutely no net

income. There should be a zero tax."

Michetti, the former housing commissioner, proposes a

program whereby small buildings in certain low income

districts wouldn't have to pay any tax at all, so long as

they maintained their apartments in decent condition. "If

you did it in a progressive way, you could at least tie it to

a standard of habitability in terms of maintenance." But

the current commissioner, Deborah Wright, says she wor-

ries that a no-tax policy in certain neighborhoods might

stigmatize the community.

There are potential problems with any tax cut plan,

however. When owners spend less on taxes, they are like-

ly to spend more on debt payments rather than funneling

that money into the cost of operating and maintaining a

building. "Often times the subsidies get capitalized into

the cost, either into more debt or a higher sales price,"

Lappin explains. "That's why it's a very complicated

problem as to how you actually structure it."

Nevertheless, Lappin says the idea is probably worth

the risk, as long as the right kind of controls are put in

place. Others disagree.

"I don't see it making sense," says a Bronx real estate

manager who stabilizes and sells foreclosed properties.

He argues that the tax relief plan would immediately in-

crease building values, leading owners to refinance their

properties with a larger mortgage, putting more cash in

their pockets while saddling the buildings with in-

creased debt.

"Small, independent buyers are like bad parents," he

adds. "You need a license to drive a car but you don't

need one to operate a building."

R

Ublk'S Cube is child's play compared to this puzzle. In a per-

feet world, as lOng as there is enough income for a landlord

to cover the cost of maintaining and operating a building,

the market should compensate for value and debt should-

n't be such a problem. It doesn't work that way in the real

world, at least it didn't in the 1980s. The tragic building

collapse on West 140th Street is only one legacy of that

unbridled market.

"The point is, there are no restrictions. Whatever

someone is willing to lend you, you can get," says Andy

Scherer. "People suffer from it every day."

There is one solution, and it's been around for many

years, adds Small of ANHD. "Maybe there is no profit for

owners in the private market in low income neighbor-

hoods. So don't throw good money after bad. Landlords

buy a building with their eyes open. They should know

what they are getting into. If they get in over their head,

they should get rid of it. Give it to a tenant group. Give it

to a nonprofit." That, he says, is what the city should be

making possible. But it's hard to imagine an idea more at

odds with the winds blowing from City Hall. 0

The end. of in rem foreclosure?

A

private consultant's report to the

city's Department of Housing

Preservation and Development sup-

ports permanently scrapping the city's

practice of taking title to buildings with

several years of tax arrears, according

to HPD Commissioner Deborah Wright.

The report also includes a number

of proposals that would set up new

means for supporting low income hous-

ing, she says. "Some are very contro-

versial, W she adds, including one that

would set a minimum rent on regulated

apartments. Another would ease the

tax burden on certain buildings.

The report, by the Arthur Andersen

consulting firm, concludes that it costs

the city an average of $2.2 million to

take a building into city ownerShip,

manage and rehabilitate it and then

sell it. This figure includes not only the

hard operating and construction ex-

pense, but also litigation costs, lost

taxes and water charges, even interest

on capital investment in the renova-

tion. Yet, the report adds, the average

building taken in such a foreclosure

action owes only $36,000 in city tax-

es. A moratorium on foreclosing on tax

delinquent properties has been in ef-

fect since before Mayor Giuliani came

into office.

Wright says instead of taking title to

properties, HPD would prefer to negoti-

ate work-out plans on individual build-

ings. "In the case of a building in mort-

gage foreclosure, we would sit with the

banks, the owners, everyone, and say

this is not viable. The hammer is we

will take the building unless everyone

around the table takes a haircut. The

bank would cut its interest, we would

cut the tax debt or drop litigation. W The

city would also help to arrange financ-

ing for repairs if the owner complied

with demands, Wright says.

Advocates say the plan sounds like a

thinly veiled effort to raise tenant rents

and gut lease protections. "I don't want

to see more buildings taken by the

city, W says Jay Small of the Association

for Neighborhood and Housing Develop-

ment. "But if you are going to restruc-

ture the debt and refinance [for repairs],

you are going to increase the rent roll

and the tenants are going to take the

hit. It's an outrage. W Andrew White

CITY LIMITS/MAY 1995/13

The money flows from

hand to hand, and

a building falls in Harlem.

14/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

T

gain a solid grasp of professional real estate investors' m0-

tives and methods, listen to how they refer to the buildings

they trade. They call the properties "sticks and bricks." And

when neophytes confuse a building's concrete foundations

and sturdy floors with a solid financial investment, the pros

call this a "sticks and bricks fixation."

That's because they have something more important on

their minds: cash, profit margins, return on investment. "It's

the cash flow that's coveted. Real estate is a mere means,"

writes Gaylon Greer, author of a popular text book pub-

lished by Dow Jones & Company.

In New York City, acknowledged to be one of the nation's

most cutthroat real estate markets, a thriving industry has

been built on the successive waves of newcomers who fail to

make accurate, realistic calculations about cash flow before

buying property. They allow themselves to be convinced

that, one way or another, the buildings they buy will be their

ticket to wealth.

Two months ago, the east wing of a large apartment build-

ing at 142 West 140th Street in Harlem collapsed, killing

three tenants and revealing in very stark terms how low in-

come people pay for the errors of ill-educated speculators.

Marcus Lehmann and Morris Wolfson, the principals be-

Ise

By Kim Nauer, Andrew White and Jesse Drucker

hind Mount Wilson Realty, the company that owns the

felled building and at least 11 others, owe millions of dol-

lars in debt on their overleveraged properties and are likely

to lose their buildings to foreclosure. They may also face

criminal charges stemming from the March 21 tragedy.

Much less evident, however, are the investors who make

profits-often big profits-from the business of slumlord-

ing. Alternately known as financiers, mortgagees or opera-

tors, this group makes loans that banks with strict credit

rules are unwilling or unable to make. They play the role of

negotiator and matchmaker, hooking up buyers, sellers and

people willing to invest capital for the high interest returns

that risky inner-city investments have sometimes garnered.

A City Limits investigation of the Harlem properties

Targeted Or.ganizing

I

n the Bronx, private financiers are

prime players in the commercial cred-

it market. That's why the Northwest

Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition

has almost completed a textbook-sized

manual for tenant organizing in debt-

burdened apartment buildings.

do a title search. There they look for

tell-tale signs of trouble:

much a building was sold for. The

mortgages will indicate how much has

been borrowed and, frequently, at what

interest rate. Here, tenants can deter-

mine if their landlord is on a tight

A key strategy of the group, which

has affiliates in 11 neighborhoods, has

been to look beyond the problem land-

lords-often recent immigrants who

naively sign steep loan agreements for

buildings with inadequate rental in-

comes-to the people who lent them

money. With luck, some well-placed

pressure on these well-heeled money

movers can relieve the worst of a build-

ing's problems, says the coalition's ex-

ecutive director, Mary Dailey.

When tenants approach the group

about problems in their buildings, the

first thing organizers do is take them

down to the Department of Finance to

First, Dailey says, tenants determine

if the loan for the building came from a

bank or a private mortgage lender. In re-

cent years, banks, which count on mak-

ing their money back over the long haul,

have tended to be more conservative

about whom they lend money to. For the

most part, loan officers want to ensure

that the monthly rental income of a

building will be enough to meet loan

payments and keep the building in good

shape. A conventional mortgage, for ex-

ample, will always have a clause allow-

ing the bank to foreclose if it is not

maintained. Private financiers, whose

goal is to maintain cash flow-not the

building-frequently scratch out or fail

to include this provision, Dailey says.

leash held by the people who lent him

money. Problem signals include low

down payments, high interest rates

and short-term loans with frequent

term extensions.

It is in the mortgage documents that

tenants will often see the genesis of

their landlord's financial problems. The

manual, due out later this year, out-

lines many of the multifarious and cre-

ative techniques financiers have used

in recent years to make money quickly.

It goes into detail on the many organiz-

ing strategies that tenants have used

over the years to challenge the folks

that hold the purse strings-and offers

valuable prescriptions for gaining the

upper hand. Kim Nauer

Next, she says, tenants are taught

to look at the money trail. By reviewing

the deeds, tenants can determine how

bought and sold by Mount Wilson over the last decade

shows that nearly all were originally purchased with capital

from the private, unregulated world of alternative financing.

Lehmann and Wolfson's financiers loaned them money-

lots of money, at very high interest rates-during the mid-to-

late 1980s, while the city's real estate market was hot and

the values of buildings in low income neighborhoods were

soaring. Impressively, but in what appears to be standard

fashion, these operators got out of the deal and took their

profits with them just moments before Mount Wilson began

to show signs of serious financial trouble.

All of this happened in a market boosted by what experts

say were wildly inflated property values made possible by

crafty financiers, reckless-often foolish-speculators, and

bankers who drove their own institutions into the ground,

only to be bailed out by America's taxpayers as part of the

Savings & Loan crisis. As a result, the federal Resolution

'Irust Corporation (RTC) ended up with hundreds of millions

of dollars worth of mortgages on inner-city properties-in-

cluding all of Mount Wilson's Harlem buildings.

Yet the financiers behind Lehmann and Wolfson made

money, and today they are still among the biggest players in

the business, plowing cash earned in New York's marginal

neighborhoods during the 1980s into investments in shop-

ping malls, parking lots and other properties around the

country. And the mortgages on Mount Wilson's buildings

have been sold by the federal government to a new set of fi-

nanciers at rock-bottom prices. According to business press

reports, these new investors expect that their multimillion-

dollar investment will yield a whopping 100 percent profit.

Jethro Chappelle, a 69-year-old resident at 75 St. Nicholas

Place, which is, for the time being, still owned by Mount

Wilson, knows that he and the other residents will never see

a penny of this windfall. Living on the fifth floor with a

wheelchair-bound son, Chappelle and other family mem-

bers have been lobbying for months to get the building'S el-

evator fixed. Chappelle adds that he and his family have

been calling building management for the last two years

about a three-foot hole in his bathroom ceiling. Rats, which

crawl on the rafters above, sometimes fall through onto the

floor below. Now Chappelle, like most tenants interviewed

for this article, just wishes he could move. "I'm sick and

tired of the whole damn thing," he says.

A

surYey of property data on five blocks surrounding the West

l40th Street building shows that during the last 10 years, only

a small minority of the private property mortgage deals in

the neighborhood have involved traditional bank financing.

It's a problem that afflicts most low income communities of

color, where high-interest alternative financing is often the

only game in town.

Unlike banks, which negotiate a mortgage to last several

decades, private financiers set up short-term deals, com-

monly called balloon mortgages, with high up-front interest

payments and early principal due dates. When the principal

comes due, the financiers have the flexibility and the op-

tion to renegotiate the deal. If, for example, the cost of mon-

ey has gone up, they can charge higher interest rates. If the

deal has begun to look shaky, they can find other investors

to buyout the mortgage loan.

On the surface, it appears that the financiers are taking a

high-risk gamble that the landlords they lend to will be able

to keep up with their mortgage payments. But real estate

watchers say the true professionals, the ones that last in this

business, know how to control their risk and get out of the

CITY LIMITS/MAY 1995/15

market before the inevitable downturns.

Mount Wilson's deals follow this pattern. Property

records show that Lehmann's and Wolfson's early forays

into the real estate business were largely privately financed,

with high-priced loans from two closely linked backstage

players well known to tenant activists in the South Bronx

and Harlem.

In the case of 142 West 140th Street, Mount Wilson

bought the six-story, 71-unit building for $525,000 from a

Yonkers businessman in January 1987. The partners put

down $100,000 in cash and signed a $425,000 mortgage note

at 15.5 percent interest with Howard Parnes, a partner in the

Scarsdale-based company, Houlihan-Parnes Realtors. At the

end of the year, Parnes attempted to sell the mortgage to Ma-

rine Midland Bank. The bank apparently balked and quick-

ly returned the mortgage to the financiers.

Parnes then sold the mortgage to Harvey Wolinetz, an-

other operator whose office shares the same Scarsdale ad-

dress. And Wolinetz turned

around and promptly loaned

the building owners-Lehmann

and Wolfson, a.k.a. Mount Wil-

son-another $175,000.

By this time, Lehmann and

Wolfson had to make mortgage

payments of $93,000 a year to

Wolinetz on this property

alone. Meanwhile, they had

purchased a dozen more build-

ings in the surrounding neigh-

borhood, mounting up debt at a

rapid pace.

They had owned the build-

ing barely a year when

Wolinetz, having collected tens

of thousands of dollars in pay-

ments and, in all likelihood,

broker's fees as well, cashed

out. Wolinetz sold the mort-

gages, and the risk, to Ensign

Savings Bank. And Lehmann

and Wolfson promptly bor- ~

rowed another $450,000 from ~

Ensign against the value of the c;,

building. ~

Because none of the players '"

in the deal returned calls from

City Limits, there is no way to know exactly what happened

to the money. A Bronx real estate operator familiar with the

process says the best analysis is simple: don't get obsessed

with the sticks and bricks, just follow the cash. Lehmann

and Wolfson put $100,000 down on the original purchase,

and after the Ensign deal they had $450,000 cash in hand.

Whether or not they reinvested any of that cash back into

the building through repair work is unclear. Lugarna

Thompson, who lived in the West 140th Street building for

54 years, say residents have had only minimal services for

the last five years.

What is known is that, within a few months of signing

the deal with Ensign Bank, Lehmann and Wolfson, under

the new name "Mount Wilson Stores," bought another

building on Flatbush Avenue near Park Slope, Brooklyn, for

$675,000. They may have been investing their Harlem earn-

ings in another part of town.

16/MAY 1995/CITY LIMITS

There are variations in the histories of Mount Wilson's

many Harlem properties. In some transactions, for example,

buildings were repeatedly flipped between Parnes affiliates

and a Brooklyn-based real estate company. But for each of

the Harlem buildings examined by City Limits, the epilogue

was the same: After a period of intense trading during the

height of the speculators' market, the mortgages were sold to

Ensign Bank. In February 1990, the bank cemented its rela-

tionship with Lehmann and Wolfson with a massive $10.5

million mortgage loan that wrapped together 13 buildings

worth a total of just $6.3 million, according to an RTC ap-

praisal one year later. The bank also loaned another $1.7

million to the pair.

Two months later, Mount Wilson stopped making their

mortgage payments to Ensign. And in September, the bank,

heavily invested in the city's collapsing real estate market,

was seized by federal regulators.

In 1990 and 1991, Lehmann and Wolfson were hit with

nearly two dozen lawsuits and liens, ranging from unpaid

oil bills to personal injury claims. Their corporation,

Mount Wilson, filed for bankruptcy protection in the fall

of 1991, owing RTC principal, interest and fees on $12.7

million in Ensign loans according to court documents.

The city was also seeking more than $800,000 in back tax-

es and other charges on their properties.

II s Lehmann and Wolfson's finances spun out of control, the lives

~ their tenants steadily wonened. Interviews with some 20 ten

ants, activists and lawyers involved with the buildings in-

dicate that the owners all but refused to do work there.

While tenants' fortunes differed depending on how well

organized they were, all reported that maintenance in the

early 1990s was done almost exclusively through the

Department of Housing Preservation and Development's

Emergency Repair Program.

With Lehmann and Wolfson protected by Chapter 11

bankruptcy proceedings, Mount Wilson's mortgages were

put up for RTC auction. They were quickly purchased,

along with Ensign's other bad debts, by an investment

group led by Lloyd Goldman, nephew of deceased New

York real estate king Sol Goldman, and investment banker

Michael Sonnenfeldt. According to Crain's New York Busi-

ness, the $45 million deal is expected to net them more

than 100 percent profit. Interestingly, Houlihan-Parnes bid

$55 million for the same failed loan package; the RTC, how-

ever, rejected Parnes' higher of-

has only taken charge of the properties in order to purchase

them. "I have always been negotiating to buy these build-

ings," he says.

fer, charging a conflict of inter-

est. RTC officials, however,