Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Determining Stakeholders For Feasibility Analysis: Doi:10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.002

Uploaded by

Alex PetracheOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Determining Stakeholders For Feasibility Analysis: Doi:10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.002

Uploaded by

Alex PetracheCopyright:

Available Formats

Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp.

4163, 2009 0160-7383/$ - see front matter 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain

www.elsevier.com/locate/atoures

doi:10.1016/j.annals.2008.10.002

DETERMINING STAKEHOLDERS FOR FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS

Russell R. Currie University of British Columbia, Canada Sheilagh Seaton Okanagan College, Canada Franz Wesley University of British Columbia, Canada

Abstract: Most techniques for stakeholder identication and salience in the pre-start up phase of a tourism development are not systematic in approach. This paper explores the utility of a systematic stakeholder analysis within a feasibility analysis. For a more inclusive assessment of stakeholder salience in the context of sustainable development, balancing the managerial lack of intrinsic stakeholder commitment, a third party perspective is added to the evaluation process. Contributing to the nal evaluation of a development proposal, the coding scheme provides practitioners with parameters for stakeholder identication and salience. While application of the theory bears limitations in quantitative measurement, the results suggest that systematic stakeholder analysis is benecial and useful in the context of feasibility analysis. Keywords: stakeholder theory, feasibility analysis. 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

INTRODUCTION Stakeholder and collaboration theory is often referenced in the literature on sustainable tourism development. The argument is in order to produce equitable and environmentally sustainable tourism developments multiple stakeholders must be involved in the process of planning and implementing the project. At the site level, however, tourism developers have few theory-based or analytic resources to assist in achieving stakeholder involvement. They need a planning framework that supports both the ideals of sustainability and the practical application of policy. Feasibility analysis offers a potential framework for planning and assessing a proposed development including identifying stakeholders. At the pre-development phase, most planners attempt to identify potential stakeholders, producing often unsatisfactory results. While the literature announces stakeholder involvement as a vital aspect of prestart up planning, most of the techniques for identifying and assessing

Russell Currie researches in the new business development and tourist behavior areas based at the Faculty of Management, University of British Columbia Okanagan, 3333 University Way, Kelowna, BC, Canada V1V 1V7. Email <Russell.Currie@ubc.ca>. Sheilagh Seaton researches special event and sport marketing and Franz Wesley researches tourist behaviors. 41

42

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

stakeholder orientation at this stage are not theory driven or systematic in approach. This paper, therefore, turns to the stakeholder theory literature for an identication and salience typology and then, through eld research, explores the utility of this systematic stakeholder analysis within feasibility analysis context. FEASIBILITY AND SYSTEMATIC STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS A signicant challenge for planners and practitioners of sustainable tourism developments is the implementation of sustainability principles at the tourism site level, where regional and destination contexts yield tangible results (Marcouiller 1997). In terms of stakeholder involvement in the planning process, often stakeholder issues and orientations will be site-specic. Considering the need for multiple stakeholder involvement in the planning process and subsequent operations, tourism operators and planners need to address the identication and voice of stakeholders in the early stages of strategic planning. Feasibility Analysis Feasibility analysis is a pre-start up and strategic planning tool, conducted in the pre-business plan phase of a development. It involves a process of collecting and analyzing data prior to the new business start up, and then using knowledge thus gained to formulate the business plan itself (Castrogiovanni 1996:803). Implementing a detailed feasibility analysis during the project planning process demonstrates how the development will operate under a specic set of assumptions (Matson 2004) considering all economic and non-economic factors (Graaskamp 1970). It is conducted at a key juncture allowing for an informed go/no go decision on a proposed development before considerable investment is made. While feasibility analysis is generally considered an important business tool, it is also subject to the debate on the usefulness and benets of strategic planning to business success. Critics of strategic planning usually refer to the rigidity and suppression of creative solutions that planning can produce (Miller and Cardinal 1994). Some studies, however, argue convincingly that pre-start up planning has concrete advantages depending on certain contexts and contingencies (Castrogiovanni 1996, Delmar and Shane 2003; Soteriou and Roberts 1998). Such contexts include a number of environmental conditions, such as uncertainty, municence, and industry maturity, and founder conditions, such as knowledge and capital (Castrogiovanni 1996). The various contexts have either positive or negative results on the effectiveness of strategic planning efforts. Basing their evaluation on the contexts in Yips (1985) article, Murphy and Murphy (2004) claim that strategic planning is particularly relevant in the tourism industry provided a plan remains exible and uid. Reecting the complexity of the tourism context and a new tourism planning paradigm, Costa states,

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

43

Tourism planning ought to be viewed from a rational and technical point of view (professionalism), which has to be matched against the particularity of every place, the needs and wishes of the people that live in the area, market forces, the availability of manpower and funding, and the position of the place in the world market. (2001:439).

In other words, strategic planning in the tourism industry is crucial in so far as it integrates multiple stakeholders, and remains adaptable to changing environmental, social and economic conditions. Castrogiovanni (1996) argues that, with all contexts considered, prestart up planning has no direct result on nancial performance, survival or other outcomes. Planning does, however, yield direct benets that bear upon the rms ability to act in a way conducive to achieving its goals and objectives. These benets include legitimization of the business, improving communication with external stakeholders, meeting expectations of many people who simply believe in pre-planning, learning through planning, increased efciency and cooperation through improved communication within the organization, and streamlining certain procedures before starting up the business (Castrogiovanni 1996). Lyles, Baird, Orris, and Kuratko (1993) propose that formal planning offers small rms a comprehensive strategic decision making process including a wide variety of alternative strategies and this in turn leads to higher levels of performance and protability. Engaging the debate on the usefulness of strategic planning, numerous studies assess the relationship of pre-start up planning to business performance, yielding mixed results. A number of authors conclude that the literature does not provide a comprehensive and consistent conclusion: that formal strategic planning results in performance success (Pearce, Freeman and Robinson 1987; Powell 1992; Schwenk and Shrader 1993). Methodological differences are potential explanations of these inconsistencies (Miller and Cardinal 1994). Despite the ambiguity in the study results, taken as a whole they do suggest that strategic planning is a benecial activity. Rue and Ibrahim (1998) nd enough support in the literature to argue that planning in small business formation can increase performance and success rate. Powell notes that among the number of studies he reviewed positive planning-performance relationships outnumbered negative ones (1992:552). And Schwenk and Shrader conclude from their meta-analysis, the overall relationship between formal planning and performance across studies is positive and signicant (1993:53). Most of these planning-performance studies examine the impact of strategic planning on nancial performance only (Bracker, Keats and Pearson 1988; Pearce et al 1987; Powell 1992; Rhyne 1986; Robinson and Pearce 1983; Schwenk and Shrader 1993). Introducing an alternative indicator for performance success, Castrogiovanni (1996) argues for business survival to be the dening success factor. In recent years, however, measuring the success of a business must involve an evaluation that goes beyond the nancials or survival. Elkington (1999) articulates the need for businesses to implement policies and practices that aim for economic, social and environmental sustainability. While previ-

44

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

ous articles on strategic planning focus on nancial success, an increasing number of studies reect the changing attitudes that strategic planning can and should have an impact beyond the nancial performance of the rm (Judge and Douglas 1998). Those studies that do examine the incorporation of environmental and social concerns into strategic planning and the subsequent results on performance are concerned with large existing rms well past the start up phase (Hart and Ahuja 1998; Judge and Douglas 1998; Ruf, Muralidhar, Brown, Janney, and Paul 2001). Very few studies measure the impact of pre-start up planning on long-term social, economic and environmental success. In the ecotourism industry, one case study examines how a pre-business plan environmental management and control system, developed in conjunction with multiple stakeholders has resulted in a successful sustainable tourism business (Herremans and Welsh 1999, 2001; Welsh and Herremans 1998). Success, then, refers to much more than nancial protability. In the tourism industry specically, the push for sustainable tourism certication (UNWTO 2003) and the recent declarations of organizations such as the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO 2002), reects the pressure for a sustainable tourism industry, one that measures success by environmental and social indicators as well as nancial. Moving beyond the ideals of sustainability as a concept and into its implementation and practice, uncovers challenges that a strategic planning tool like feasibility analysis could help overcome. One such challenge is the fragmented nature of tourism planning (Berno and Bricker 2001; Ioannides 1995; Ladkin and Bertramini 2002; Soteriou and Roberts 1998). Integrative links for effective planning are few between all levels of planning from the international level down to the site itself. Without common goals and vision, tourism site operators may plan independently of broader concerns and policies. Murphy and Murphy note that often entrepreneurs initiate tourism development, but their personal motivations may not necessarily reect what is best for the overall community (2004:372). Furthermore, tourism planning can also occur independent of other local planning approaches and policy, such as land use planning, natural resource management and community economic development schemes (Dredge 1999). A single pre-start up study offers common language and substantive information, which various sectors, planners, and stakeholders can then discuss (Castrogiovanni 1996). Feasibility analysis thus serves as an intersectoral link, connecting policies made at higher levels of planning to their implementation at the site level. In this scenario, pre-determined public policy determines the factors and criteria for feasibility and each tourism site proposal must conduct the analysis based on these factors. A further advantage to having a strategic planning tool at the site level is that it focuses on local particulars and specics while still adhering to wider policies built on sustainable principles, thus linking the strategic and the normative (Costa 2001). Baud-Bovy (1982) asserts that an early assessment of social, cultural, environmental and economic implications of a tourism development

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

45

could alleviate obstacles to the implementation of sustainable development policies. The current emphasis on nancial indicators for success in both the strategic planning/performance studies and in the feasibility analysis templates does not reect the growing trend of sustainable developments. Consequently, the literature on pre-start up planning, and templates for feasibility analysis, does not clearly offer feasibility analysis as an aid in the implementation of policies that take into account social, economic, and environmental concerns in general at a specic locale. Shen, Wu, and Wang (2002) recognize the same deciency in the construction industry, noting a current lack of guidance for actually implementing the principles of sustainability. Their study sees a solution in strategic planning, proposing a quantitative feasibility analysis model for sustainable construction developments. While often associated with nancial feasibility such as cost-benet analysis and return on investment, given a broader denition, feasibility analysis is poised to make a more holistic assessment of a proposed tourism development. A few feasibility analysis templates and handbooks suggest the inclusion of a broader range of factors, but none are exhaustive or conclusive. As a whole, these templates usually prescribe some combination of economic, environmental and social/cultural impact assessments, dening the goals and objectives of the project, dening the criteria that will determine the go/no go decision, identifying legal and policy issues, assessing management and technical issues, site analysis, market and nancial analyses, and the generating and evaluating of alternatives (Angelo 1985; Barret and Blair 1982; Behrens and Hawranek 1991; Canestaro 1989; The Economic Planning Group of Canada 2005; Erfourth and Agosta 2002; Etter 1988; Geltner and Miller 2001; Graaskamp 1970; Hofstrand and Holz-Clause 2004; Myers, Lawless, and Nadeau 1998; Neal and Trocke 2002; Reilly and Millikin, 1996; Smith 2002; West 1993). In addition to the aforementioned factors, one important aspect of a pre-start up study is an identication of potential stakeholders. Various scholars make the call for stakeholder identication and involvement early in the planning process (Murphy and Murphy 2004; Sautter and Leisen 1999; Simpson 2001). In the pre-business plan phase, stakeholders are involved at the point where major decisions and signicant nancial and emotional investments have not yet been made, there is little forward momentum to redirect (Chrisman and McMullan 2000), and the tourism development has not yet affected the environment and society. Indeed, such initial involvement would avoid the costs of major stakeholder conicts later on. According to Sautter and Leisen, tourism planners should proactively consider the strategic orientations of all groups affected by the venture before proceeding with development efforts. As congruency across stakeholder orientation increases, so does the likelihood of collaboration and compromise (1999:318). The literature, furthermore, strongly supports the claim that stakeholder involvement plays a vital role in sustainable tourism development (Sautter and Leisen 1999); as Clarke and Roome (1999) assert, consideration for social and environmental issues requires the identi-

46

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

cation of numerous stakeholders and the incorporation of their opinions. Hardy and Beeton (2001) argue that understanding stakeholder perceptions should be viewed as a prerequisite for sustainable tourism. In the context of community tourism planning, widespread stakeholder participation will ensure all major issues are addressed, leading to decisions that will be tenable in the long-term (Murphy and Murphy 2004). Recognition of the strategic value of stakeholder involvement and early stakeholder assessment has not translated into research at the pre-start up phase. Most studies involving identication of stakeholders provide analysis after planning and implementation are underway (Aas, Ladkin and Fletcher 2005; Hardy and Beeton 2001; Medeiros de Araujo and Bramwell 1999; Sheehan and Ritchie 2005; Timothy 1999; Yuksel, Bramwell and Yuksel 1999). Medeiros de Araujo and Bramwell (1999), for example, identify and survey stakeholders after the developments initial planning and implementation stage. They conclude that those stakeholders advancing social/cultural and environmental issues were underrepresented in the planning phases. This underscores the need for a strategic planning tool that incorporates stakeholder analysis prior to implementation of the plan if the principles of sustainability are to be integrated. No research articles were identied that explores the application of a systematic stakeholder identication scheme at the pre-implementation phase of tourism planning. Review of the literature suggests that an early assessment of stakeholder orientation and all other pertinent issues is an important strategic step for sustainable tourism developments. Systematic stakeholder analysis, therefore, can and should t within the domain of feasibility analysis. Nevertheless, the literature on feasibility analysis and pre-start up planning does not offer a framework for determining stakeholder status. While many techniques are available to involve stakeholders in the tourism planning phase (Yuksel et al 1999) there is no template for identifying these stakeholders during pre-start up planning. Some studies hint at the varying methods that planners use for identifying stakeholders in tourism developments; these include open meetings, review of local sources, relationship mapping and interviews (Medeiros de Araujo and Bramwell 1999; Yuksel et al 1999). These methods, however, are not necessarily theory driven or systematic in approach or analysis. Increasingly, tourism planners and managers need to look deeper than cursory reports of the more obvious stakeholders (Sautter and Leisen 1999). Therefore, this paper turns to stakeholder theory for a systematic stakeholder analysis framework and then explores its utility for feasibility analysis. As stakeholders are identied, planners in collaboration with numerous stakeholders could conduct feasibility analysis. In moving from tokenistic forms of public participation to a more collaborative and partnering form (Lane 2005), using a common framework to collectively plan, set goals and objectives, and evaluate a proposed development would empower stakeholders from the outset.

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

47

Stakeholder Theory Stakeholder theory literature provides numerous processes for explaining stakeholder identication and salience (Borrini-Feyerabend 1996; Daniels and Walker 1996; Engel and Salomon 1997; Grimble and Chan 1995; Mitchell, Agle and Wood 1997; Savage, Nix, Whitehead and Blair 1991; Vos 2003). Most of the processes are descriptive and derive their basis from original ideas put forth by Freeman (1984). Freemans often cited denition describes a stakeholder as any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organizations objectives (1984:46). Freemans denition is very broad and inclusive. In fact, one of the primary critiques of Freemans approach is that the possible number of stakeholders is unlimited and could include competitors and media (Donaldson and Preston 1995). In terms of natural resource attractions, for example, the list of applicable stakeholders would include not only individuals and groups associated with the project, but also society and future generations. Freemans (1984) denition requires all claimants of stakeholder status to receive recognition as actual stakeholders; in practical terms, however, management needs to effectively prioritize stakeholder claims. Treating each potential stakeholder as equal will be cost ineffective and will potentially conclude in a stalemate with opposing positions. Prioritising claims will allow management to position their forces and allocate resources in a systematic response. The questions then become what parameters determine salience and from whose perspective are these parameters analyzed? Stakeholder theory raises interesting questions of perspective in the identication of stakeholders. Most studies and models present stakeholder analysis from the perspective of CEOs and managers (Agle, Mitchell and Sonnenfeld 1999; Mitchell et al 1997; Savage et al 1991; Sheehan and Ritchie 2005; Vos 2003). Indeed, Mitchell et al (1997) strongly state that managements perspectives dictate stakeholder salience. In that case, the priority given to one stakeholder over another is valid only from a managerial perspective, which could be problematic in the context of social and environmental responsibility. The literature suggests that if managers alone determine stakeholder salience, then attention to those groups or individuals representing social and environmental concerns depends upon two factors. In the rst instance, managements internalization of some social or environmental issue or the rms moral commitment to uphold stakeholders interests inuences strategy and nancial performance. In the second instance, managers take a strategic approach, responding to stakeholder pressure and only when such action could result in nancial gain (Berman, Wicks, Kotha and Jones 1999; Winn 2001). One study, however, shows no support for what the authors call the intrinsic stakeholder commitment (Berman et al 1999). Instead, their study concludes that managers attend to stakeholder concerns only when such action is perceived to enhance nancial performance (Berman et al 1999). In a more recent article, Sheehan and Ritchie (2005) ask CEOs of tourism destination management organizations to identify

48

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

stakeholders in their existing projects. None of them identied special interest groups that represent environmental or social/cultural concerns. These results underscore the socially constructed nature of stakeholder identication and salience. Stakeholder analysis is not a formula for ensuring equitable and environmentally sustainable developments, but instead its success in this regard can only follow the advancement of democratic ideals in society at large (Grimble and Wellard 1997). Given this reality, in the absence of a managerial intrinsic stakeholder commitment, then, other perspectives are needed for a more inclusive assessment of stakeholder salience in the context of sustainable development. The other question, what determines salience, involves dening parameters for stakeholder identication. The literature offers several processes for differentiating stakeholders, most categorizing them in generic groups. Clarkson (1995), for example, differentiates stakeholder groups into primary and secondary; the corporation depends on the primary stakeholders for its survival, while secondary groups are not essential but have inuence or are inuenced by the corporation. Savage et al (1991) classify stakeholders as four types depending on two dimensions: their potential for cooperation and their potential for threat. Hardy and Beeton (2001) differentiate four generic groupings: locals, operators, tourists and regulators. The difculty with a priori generic groupings, however, is that this approach ignores the heterogeneity of groups and the plurality of stakes (Winn 2001). Reporting on several issues in stakeholder theory, Harrison and Freeman (1999) call for a ner-grained typology of stakeholder groups. This task requires development of a stakeholder theory of identication and salience. While other theories exist (for example, Savage et al 1991), this paper applies the Mitchell et al (1997) theory because it meets several requirements suggested in the literature: it allows for site-specic inuences (Simpson 2001); it offers a ner-grained typology than generic groups (Harrison and Freeman 1999); and it is normative as well as descriptive (Donaldson and Preston 1995). Mitchell et al aim for a theory that can explain to whom and to what managers actually pay attention [. . .and identies] those entities to whom managers should pay attention (1997:854). Towards this goal, their theory proposes a more precise typology of stakeholders by introducing three attributes rather than creating generic groups. Mitchell et als theory states [s]takeholder salience will be positively related to the cumulative number of stakeholder attributespower, legitimacy, and urgencyperceived by managers to be present (1997:873). Because these attributes are not restricted to generic guideline categories, this typology also allows for site-specic inuences. The theory as presented in Mitchell et al (1997) is adequate for the purposes of this article. Because this paper explores the utility of systematic stakeholder analysis in the pre-start up phases, it is not concerned at this point with altering stakeholder theory. At issue is the potential contribution of stakeholder theory to feasibility analysis. Mitchell et al (1997) depict their theory in a Venn diagram of three sets, with each set representing one of the three attributes. All groups

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

49

or individuals gain salience in stakeholder status depending upon the cumulative number of stakeholder attributes: the greater the number of attributes the higher the salience of the stakeholder. In the Venn diagram, then, the more sets to which the stakeholder belongs, the greater the salience. Stakeholders possessing only one attribute are termed latent stakeholders; with two attributes, expectant stakeholders; and with all three attributes, denitive stakeholders (Table 1). Entities perceived as having none of the three attributes will not be stakeholders and have no salience. Depending upon the number and type of attribute, the stakeholders needs are different as is their ability to inuence the management of the development. Mitchell et al (1997) justify the three attributes from the literature, noting many stakeholder scholars who contend that stakeholder selection is often based solely on the legitimate claims of potential stakeholders, which reduces the importance of power and urgency. Mitchell et al dene power as the extent to which a party has or can gain access to coercive, utilitarian, or normative means, to impose

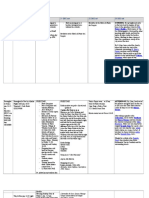

Table 1. Stakeholder Attributes, Classication and Identication Typology

Attributes Classication of Stakeholders Latent Stakeholders Identication Typology

Power

Legitimacy

Urgency

Power and Legitimacy

Expectant Stakeholders

Power and Urgency

Legitimacy and Urgency

Power, Legitimacy and Urgency

Denitive Stakeholder

Dormant Stakeholderswhile holding power, they lack legitimacy and urgency, therefore power is often unused Discretionary Stakeholderholding no power or urgency to inuence the organization Demanding Stakeholderholding urgent claims yet lack the power or legitimacy to inuence the organization Dominant Stakeholdersthey have legitimate claims and the ability to act upon these claims by the power they hold Dangerous Stakeholderlack legitimacy yet has the power and urgency to inuence the organization Dependent Stakeholderlack the power to carry out their urgent legitimate claims and therefore have to rely on others power to inuence the organization Denitive StakeholderHolding all three attributes the stakeholders has the ability to inuence the organization in the immediate future

Adapted from Mitchell et al (1997).

50

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

its will in the relationship (1997:869). Legitimacy is dened as a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and denitions (Mitchell et al 1995:574). Urgency is dened as the degree to which stakeholder claims call for immediate attention (Mitchell et al 1997:870). While presenting the three attributes as more reliable than previous theories, Mitchell et al (1997) also recognize possible limitations to the practical application of the model based on the appropriateness and measurement of the three attributes: power, legitimacy and urgency. They raise the following questions:

1. Are power, legitimacy and urgency appropriate for measuring stakeholder salience? 2. Are the attributes clearly dened and distinct from one another? 3. What is the effect of not being able to quantify each attribute on a continuum?

Further questions also arise, namely the challenge of identifying stakeholders despite the dynamic nature of their position. Stakeholders are not static entities; therefore, movement between categories is possible (Mitchell et al 1997). In fact, stakeholders often try to acquire new attributes by varying means: coalition building, political action, social persuasion and economic dependence (Mitchell et al 1997). For example, a conservation group complains repeatedly to a resource extraction company about changing its behaviour, to no avail. The conservation group then decides to inform the local government about a resource extraction company not abiding by regulations, thus using the local government as an ally to change the resource extraction companys behaviour. Another limitation of the theory is the lack of quantiable measurement for the attributes. Mitchell et al acknowledge this limitation, stating that [t]o build our identication typology, we treat each attribute as present or absent, when it is clear that each operates on a continuum or series of continua (1997:881). Mitchel et als (1997) framework is designed to explain how existing managers perceive stakeholders and prioritize stakeholder interests. A previous study tested the theory, nding strong support for the relationship between the three attributes and salience (Agle et al 1999). While that study supports the descriptive nature of the theory, its normative elements suggest potential for application in an objective sense. This paper explores the theorys capacity to identify potential stakeholders and predict their orientation vis-a-vis a new tourism develop` ment. In using the theory in this manner, the researchers make one signicant amendment. To account for the criticisms of manager-driven bias and the lack of a managerial intrinsic stakeholder commitment, a third party (researchers) is introduced that advocates for intrinsic stakeholder commitment and becomes another perspective in determining salience. While the third party too brings a bias, they do provide legitimate perspective.

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

51

Stakeholder analysis theory could potentially ll the gap in the feasibility analysis literature with a stakeholder identication process. This paper explores the application of a systematic stakeholder analysis framework to an objective pre-start up feasibility analysis. What methodological issues arise in the process? What are the benets of applying a systematic stakeholder analysis at the pre-start up phase of a development? Study Methods In this study, Mitchell et als (1997) theory is applied to the feasibility analysis of a potential land and water trail located on the Northwest Coast of British Columbia, Canada. This particular setting offers a highly relevant context for applying a theory for stakeholder identication and salience; nature-based tourism and recreation developments often affect a variety of groups, organizations and individuals (Grimble and Wellard 1997). Water trails are similar to other natural resource developments in this regard; because of the distance covered by the trail, natural barriers or borders between interest groups are often crossed. Water trails can connect private residential property, commercial and sport shing grounds, First Nations lands, resource extraction industries, and pristine wilderness. Hence there is often competition and variances in the management and development of water trails. To further complicate the potentially tense relationship between these individuals and groups, each of the special interest groups often claim stakeholder status along with rights and privileges. Therefore, development and operation of a water trail leads to the question articulated by Freeman (1994) as The Principle of Who or What Really Counts. While the interests of all groups affected by the water trail demands recognition, not all interests will t in a feasible manner to ensure sustainability of the project; thus, management must determine among competing voices, a structure that will allow them to recognize stakeholder status and prioritise stakeholders claims. The Tsimshian Nation has the physical land and water base and the human resources to create water trail systems that will attract outdoor and adventure enthusiasts. Due to the growth of the outdoor and adventure tourism industry, land and water trail systems are becoming increasingly lucrative. Historically, however, developments in the northern regions of British Columbia become controversial because of the sensitive nature of the environment and the ongoing discourse in land ownership between the First Nations and government agencies. Therefore, before investing millions of dollars in a natural resource attraction that will affect the Tsimshian Nation and also surrounding communities, businesses, not-for-prot agencies, governmental and non-governmental organizations, special interest groups, the shing, logging, transportation and tourism industries, a feasibility analysis needs to be conducted in order to determine sustainable viability. A rst step in this project consisted of identifying leaders for the feasibility analysis phase of the project and to then set objectives for the

52

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

feasibility analysis. The researchers identied the Tsimshian Tribal Council Administration as project leaders who, in consultation with the researchers, set management objectives for the feasibility analysis and determined potential benets of a water trail to the Tsimshian Nation and surrounding communities. Benets sought for the Tsimshian Nation are both immediate and long-term: creating own source revenues, sustainable development, economic diversication and training and management opportunities for all members of the Tsimshian Nation. In addition, other First Nations and communities in the region should derive the benets, similar to those of the Tsimshian Nation, from the water trail. The researchers next step was to develop an exhaustive list and evaluation of potential stakeholders. Each member of the project team independently developed a list of possible stakeholders. Initial development of the list utilized the key informant approach. This approach involves the gathering of data collected from structured contacts with experts or inuential leaders and is useful where qualitative descriptive information is sufcient for decision-making. . . [and] when there is a need to understand motivation, behaviour, and perspectives (USAID 1996:1). The initial stage in the key informant approach is the careful identication and selection of these individuals. The researchers asked the Tribal Council to identify whom they considered the most inuential leaders (both for and against the proposed development). The researchers then met with these government ofcials, members of the business community, NGOs and tribal members to assess their potential involvement in the proposed water trail development. In this initial meeting, the researchers also requested these key informants to identify others who might affect or be affected by the project. This snowball sampling was an attempt to ensure a wider representation of interests and further minimize the impact of researcher bias in the selection process. Following this initial record of potential stakeholders, the researchers used content analysis to further expand the list. Scholars consider content analysis a qualitative research methodology useful for discovering, describing and categorizing the focus of individual, institutional, or social attention (Stemler 2001). The researchers conducted a content analysis on the relevant literature found in the websites, publications, and mission statements of the Tsimshian First Nation, businesses, NGOs and the local community. The literature produced in other similar tourism sites also provided useful information. Inferences made from this information to potential group or individual involvement or interest in the proposed water trail lead to inclusion in the list. The Tsimshian Tribal Council Administration and the researchers used both key informant and content analysis methods to ensure that each approach had some method of corroboration, since inferences were sometimes made from the data collected. Following the development of these independent lists, the team combined the lists to make one exhaustive compilation. Agreement between individual researchers and Tribal Council was not necessary for inclusion in the combined

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

53

potential stakeholder list. For an initial classication of all potential stakeholders, the population was divided into ve categories: Federal Government Agencies, Provincial Government Agencies, Crown Corporations, First Nations, and Local Governments, Businesses and various Socio-Economic Organizations. Researchers placed potential stakeholders under the relevant classication and identied their potential to inuence the projects objective. An exhaustive list now completed, the Mitchell et al (1997) theory provided the coding scheme with which to further dene and categorize the potential stakeholders. The two eld researchers, based on experience and knowledge of natural resource tourism development, feasibility analysis, and social, political and economic issues, independently evaluated each of the potential stakeholders. Each researcher assigned the attributes of power, legitimacy and urgency, if applicable, to the potential stakeholders. In order to account for possible future relationships, the researchers evaluated the nature of each relationship and made predictions as to the likelihood of a stakeholder moving between classications should they acquire or lose attributes. Since both the evaluations of current and future relationships were subjective and across a wide spectrum of potential stakeholders, the researchers gave much latitude in assigning attributes. This improved the interrater reliability. The process of assigning attributes was iterative. The researchers discussed discrepancies regarding the initial assignment of attributes. Subsequently, researchers returned to previous data acquired through the key informant and content analysis and accessed any new supporting materials (mission statements etc.) from which to infer the potential future interests of stakeholders. Mutual agreement between researchers on attributes assigned was reached as the different researchers coded the same stakeholders with the same attributes. Results The researchers and project leaders formed the list of potential stakeholders using various methods in an attempt to minimize bias and ensure a wide representation of interests and concerns. Not only were the key informants included in the list of potential stakeholders, but they also recommended other possible stakeholders in the project. The resultant list included: Industry CanadaAboriginal Business Canada, Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management, Tourism British Columbia, Tsimshian Nation & Tribal Council, City of Prince Rupert, various Environmental Groups with interest in wildlife, oceans and forests, such as the Raincoast Conservation Society, Valhalla Wilderness Society and the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, numerous recreation groups, and the sheries industry. In total, 21 stakeholders were identied. These groups represented a great diversity in position, from potential partners in marketing and funding to potential conicts for land and water use. The two eld researchers conferred the attributes to each of the potential stakeholders.

54

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

Figure 1 illustrates the number of stakeholders in each typology and depicts the perceived amount of stakeholder salience using the three overlapping circles as dened by Mitchell et al (1997). The stakeholders located in all three overlapping circles are labelled denitive stakeholders, possessing the greatest salience, and are more likely to inuence management objectives in the course of the feasibility analysis. The denitive stakeholders were the largest group including the Tsimshian Nation, Land and Water British Columbia, a government agency concerned with land and water usage, natural resource industries and the transportation industry. Dangerous, dominant and dependent stakeholders are those in two sets. These stakeholders have less salience than the denitive stakeholders and include government enforcement agencies, environmental groups, sheries, and the tourism and hospitality industry. The stakeholders with the least amount of salience are described as latent stakeholders. In the latent category, there are two discretionary stakeholders, local government and local recreation interests, and two demanding stakeholders, the aquaculture industry and Tourism Prince Rupert. The stakeholders, which were determined to have no inuence for the purpose of a feasibility analysis, are listed outside the concentric circles and are described as currently disinterested stakeholders. This group included Industry CanadaAboriginal Business Canada, and Tourism British Columbia. Table 2 outlines a sample of the stakeholder classication, detailing the attributes and reasons for their assessment.

POWER

0 Dormant Stakeholder 1 Dangerous Stakeholder 1 Dominant Stakeholder

LEGITIMACY

7 Definitive Stakeholder

2 Demanding Stakeholder

2 Dependent Stakeholder

2 Discretionary Stakeholder

URGENCY

6 Currently Disinterested Stakeholders

Figure 1. Stakeholder Conguration

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

55

Table 2. Sample Evaluation of Stakeholders Represented by Stakeholder Classication

Stakeholders Non Stakeholders Industry CanadaAboriginal Business Canada Tourism British Columbia Latent Stakeholders RecreationExamples: Fishing, Boating, Biking, Hiking, Local Use Aquaculture Attribute Identication Typology

Holding no attribute at this time.

Currently Disinterested Stakeholders

Legitimacyestablished land owner and resource usage Urgencypotential conicts could result in land/water use restrictions Powerbased on legal authority Legitimacyprovided by government representation

Discretionary Stakeholder

Demanding Stakeholder

Expectant Stakeholders Government Enforcement AgenciesExamples: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Ministry of Forests, Ministry of Energy and Mines Environmental Groups with interest in wildlife, ocean and forest Tourism and Hospitality Industries

Dominant Stakeholder

Urgencyprotection of natural resources Powerability to impose political will Legitimacyestablished tourism businesses Urgencydesire to encourage tourism Powerbased on participation in project Legitimacyprovided by representation of bands Urgencydened by parameters of project Powerbased on legal authority Legitimacyprovided by democratic service Urgencyprovided by direct involvement in BC land use issues Powercurrent control of forest and land resources Legitimacycurrently hold range and forest tenures Urgencypotential conicts could result in restrictions or changes in resource usage Powerlegal ownership of land Legitimacyestablished transportation infrastructure Urgencypotential conicts could result in restrictions to proposed trail

Dangerous Stakeholder

Dependent Stakeholder

Denitive Stakeholders Tsimshian Nation & Tribal Council

Denitive Stakeholder

Land and Water British Columbia

Denitive Stakeholder

Natural Resource Industries Examples: Forestry, Logging, Ranching, Mining, Oil and Gas

Denitive Stakeholder

TransportationExamples: Rail Road Water Air

Denitive Stakeholder

56

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

Discussion An important aspect of stakeholder salience mentioned in the literature review is the question of perspective. While in Mitchell et als (1997) methodology only the rms managers identied and rated stakeholders, for this study the position of those involved in the process were broadened to include members of the tribal council and the researchers. This allowed for differing perspectives on salience, thus contributing to the discussion on the theorys utility for feasibility analysis. The literature review showed that when managers assess salience, they generally overlook social and environmental concerns. But this study shows that the Mitchell et al (1997) theory accommodates these groups within the parameters of power, legitimacy and urgency. The explanation for the previous lack of environmental and social representation in the stakeholder set must then rest on the managerial perspective. Because selection of stakeholder groups will reect the values of those selecting (Yuksel 1999), involving parties other than management or the organizations directors ensures a wider more comprehensive list of stakeholders and a less biased assessment of salience. Moreover, when assessed in the pre-start up phase of a development, salience does not need to be subject only to managers and their particular bias. The results of this study indicate that groups representing the environment and local communities are present in the eld of stakeholders; managers should pay attention to them. They are classied as either expectant or denitive stakeholders, holding two or three of the attributes of power, urgency and legitimacy. In this regard, the theory is a potentially powerful framework for wide stakeholder involvement at an early stage of a sustainable tourism development. The results of the study also offer for discussion the possible limitations of the appropriateness, measurement, and distinction of the three attributes. In terms of appropriateness, though some scholars claim precedence for legitimacy over power and urgency (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Freeman 1984), assessing power and urgency provides a more detailed description of potential stakeholders. For example, environmental groups are typed as dangerous stakeholders in the development of the water trail. In this typology, that means they possess urgency and power, but not legitimacy. The environmental groups could gather support and obtain global persuasion to impose their ideals on the future of the proposed development. In addition, given the researchers experience in natural resource development, environmental groups will demand immediate involvement in any proposed developments and therefore possess urgency. In this case study, however, potential actions of environmental groups to prevent the proposed development, would not be considered desirable, proper or appropriate actions as dened within socially acceptable norms, values or beliefs of the region because they do not have control of the resources in the region. This example illustrates the importance of not limiting stakeholders to only groups who possess a legitimate claim, but expanding to a broader and more exible denition that includes power and urgency. Moreover, in terms of distinction between attributes, it is

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

57

possible to distinguish legitimacy and power given Mitchell et als (1997) denitions. It is evident that environmental groups do have the power to impose ideals on the Tsimshian Nation, but are not perceived to have control of the resource within the social norms of the region. In the domain of feasibility analysis, this example also shows the utility of a systematic stakeholder analysis theory. One advantage of this particular typology is its common language, which allows managers and planners to discuss the nuances and dene the issues surrounding each potential stakeholder in terms of the three attributes. The appropriateness of the typology does have some limitation. The application of the term dangerous to environmental groups in this study suggests a weakness in Mitchell et als (1997) typology in the context of sustainable tourism. From the perspective of collaboration and compromise, the term communicates a non-collaborative approach. At issue is the willingness of planners to redistribute legitimacy in order to create an environment where partnerships and compromise can develop. This requires a strategy for managing stakeholders, which is not immediately imbedded in Mitchell et als (1997) theory (Sheehan and Ritchie 2005). Limitation in terms of measurement is an issue, but this does not bear strongly on the utility of the theory at the pre-start up phase. The Mitchell et al (1997) theory does not provide a method to quantify the amount of power, legitimacy or urgency that each stakeholder possesses. The theory provides a general overview of stakeholder conguration with three classications of stakeholders: latent, expectant and denitive, and eliminates currently disinterested stakeholders. The value of the model is the ability to determine amongst competing voices which stakeholders possess the capacity to inuence the feasibility of the development. At this stage in planning, quantifying the degree of power, urgency or legitimacy is not as important as the identication of stakeholders and an understanding of the stakeholder relationships. The result of applying the model is a stakeholder conguration that management can use to recognize stakeholder status and broadly prioritise stakeholder claims within the parameters of the feasibility study. Measurement in the domain of feasibility analysis could also be reframed as the ability to place boundaries on the number of potential stakeholders. One of the difculties in adopting traditional stakeholder theory is that the number of potential stakeholders is unlimited. The difculty is particularly true in assessing the development of a natural resource attraction that will directly and indirectly have implications for outdoor and adventure tourism as a whole. Application of the Mitchell et al (1997) theory provides a denable boundary by limiting potential stakeholders to only those who possess power, legitimacy, and/or urgency with respect to inuencing management or managements objective. The theory simplied the process of identifying potential stakeholders by enabling the researchers to start with stakeholders that strongly possessed one or more attributes and moving outwards to include stakeholders that only weakly displayed one attribute. The limit for stakeholders was reached when potential stakeholders were identied who no longer possessed one of the three

58

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

attributes. The application of the theory provided a boundary that is clearly dened and systematically applied during the process of identifying potential stakeholders. Mitchell et al (1997) identies a potential limitation in the application of the theory resulting from a static model representing dynamic stakeholder relationships. This study explored the application of the theory during a feasibility analysis. At this stage of a proposed development, the relationship with stakeholders is often non-existent and the outcome of possible relationships is undetermined. Although the outcome of the theory is a static representation of stakeholder conguration, the model provides some exibility by enabling the researchers to make assumptions regarding the future progression of relationships and incorporating the predictions in the measurement of stakeholder salience. The adjustment enabled the researchers to include stakeholders in the study that initially appeared insignicant, but in the future may be expectant or denitive; in addition, it excluded potential stakeholders whose future relationship for the purpose of the feasibility study was determined to be insignicant. CONCLUSION The purpose of this study was to explore the benets of incorporating stakeholder theory and application to the feasibility analysis of a natural resource attraction. One advantage of this application was the ability in the pre-start up phase of a development to gain multiple perspectives on stakeholder salience. While the original intention of stakeholder theories like Mitchell et als (1997) is to explain the managerial perspective, for sustainable developments this limitation can leave social and environmental concerns underrepresented. Widening the perspective does mitigate some of the managerial bias. Determining stakeholder orientation using the three attributes of power, legitimacy and urgency is benecial in a number of ways. First, the three attributes provide common language based on dened characteristics with which multiple project leaders can discuss stakeholder issues. Second, in practical terms, the systematic stakeholder analysis clearly delimits stakeholders. The theory identies and classies stakeholders based on the presence or absence of three attributes. The structured process of assigning attributes provides a justiable and denable boundary for distinguishing between stakeholders and currently disinterested stakeholders. And third, the model allows for informed predictions, which are particularly valuable for a feasibility analysis, where stakeholder relationships are often undetermined. Mitchel et als (1997) theory denes three elements of salience, each of which can be isolated for the purposes of predicting the nature of a potential stakeholder relationship. This study examines the application of the model for one specic purpose, determining stakeholder salience relevant to the feasibility analysis of a natural resource attraction. Within this context, the model effectively provides a pragmatic typology with a justiable measure of stakeholder salience.

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

59

This paper also suggests that a combination of strategic planning and stakeholder theory is a possible solution to some of the challenges of implementing the ideals of sustainable tourism development. While a feasibility analysis embodies the elements of strategic planning, such as an emphasis on goal and target specication, quantitative analysis and prediction of environment, identication and evaluation of alternative policy actions, and an evaluation of means against ends, the incorporation of stakeholder theory can empower various interests in the planning process. The interests of other entities concerned with social/cultural and environmental impacts will thus balance the managerial lack of intrinsic stakeholder commitment, which can lead most strategic plans to focus on nancial returns. Given the multiplicity of stakeholders groups and stakeholder interests reected in the study results, this study shows the benets of applying stakeholder analysis to feasibility analysis. Considering the wide recognition that sustainable tourism must encompass various and often competing interests, it is not surprising that current planning literature rejects the notion of a homogenous public interest (Lane 2005). With multiple stakeholders identied and involved, the tourism project stands a better chance of achieving the triple bottom line. Further research should incorporate the strategies and methodologies of facilitating collaborative planning at the pre-start up stage. There is at this point, however, no denitive critical study of a pre-start up feasibility analysis. Could, for instance, a suitable framework exist for feasibility analysis that would assist planners in facilitating collaborative decision-making before major decisions have already been made? Does feasibility analysis distinguish between operational and nancial feasibility, and long-term viability versus initial revenue surpluses? How does feasibility analysis compare with other planning techniques concerned with sustainability? Considering the call for implementation strategies for sustainable tourism, further research in planning at the site level and at the pre-business plan stage is needed. Understanding the role of feasibility analysis in decentralized planning, integrative and intersectoral planning, and facilitating collaboration will address some of the challenges of implementing sustainable tourism development. REFERENCES

Aas, C., A. Ladkin, and J. Fletcher 2005 Stakeholder Collaboration and Heritage Management. Annals of Tourism Research 32:2848. Agle, B., R. Mitchell, and J. Sonnenfeld 1999 Who Matters to CEOs? An Investigation of Stakeholder Attributes and Salience, Corporate Performance, and CEO Values. Academy of Management Journal 42:507525. Angelo, R. 1985 Understanding Feasibility Studies: A Practical Guide. East Lansing: Educational Institute of the American Hotel and Motel Association. Barrett, V., and J. Blair 1982 How to Conduct and Analyze Real Estate Market and Feasibility Studies. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

60

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

Baud-Bovy, M. 1982 New Concepts in Planning for Tourism and Recreation. Tourism Management 3:308313. Behrens, W., and P. Hawranek 1991 Manual for the Preparation of Industrial Feasibility Studies. Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Berman, S., A. Wicks, S. Kotha, and T. Jones 1999 Does Stakeholder Orientation Matter? The Relationship Between Stakeholder Management Models and Firm Financial Performance. The Academy of Management Journal 42:488506. Berno, T., and K. Bricker 2001 Sustainable Tourism Development: The Long Road from Theory to Practice. International Journal of Economic Development 3. Borrini-Feyerabend, G. 1996 Collaborative Management of Protected Areas: Tailoring the Approach to the Context. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. Bracker, J., B. Keats, and J. Pearson 1988 Planning and Financial Performance Among Small Firms in a Growth Industry. Strategic Management Journal 9:591603. Canestaro, J. 1989 Rening Project Feasibility. Blacksburg: The Rene Group. Castrogiovanni, G. 1996 Pre-Start up Planning and the Survival of New Small Businesses: Theoretical Linkages. Journal of Management 22:801822. Chrisman, J., and E. McMullan 2000 A Preliminary Assessment of Outsider Assistance as a Knowledge Resource: The Longer-Term Impact of New Venture Counseling. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 24:3753. Clarke, S., and N. Roome 1999 Sustainable Business: Learning-Action Networks as Organizational Assets. Business Strategy and the Environment 8:296310. Clarkson, M. 1995 A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. The Academy of Management Review 20:92117. Costa, C. 2001 An Emerging Tourism Planning Paradigm? A Comparative Analysis Between Town and Tourism Planning. International Journal of Tourism Research 3:425441. Daniels, S., and G. Walker. 1997 Rethinking Public Participation in Natural Resource Management: Concepts from Pluralism and Five Emerging Approaches. FAO Workshop on Pluralism and Sustainable Forestry and Rural Development. Rome, December 912, 1997. Delmar, F., and S. Shane 2003 Does Business Planning Facilitate the Development of New Ventures? Strategic Management Journal 24:11651185. Donaldson, T., and L. Preston 1995 The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Academy of Management Review 20:6591. Dredge, D. 1999 Destination Place Planning and Design. Annals of Tourism Research 26:772791. Elkington, J. 1999 Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. Oxford: Capstone Publishing. Engel, P., and M. Salomon 1997 Facilitating Innovation for Development. Amsterdam: KIT. Erfourth, W., and R. Agosta 2002 Feasibility Studies. Journal of Construction Accounting and Taxation 12(5):2528.

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

61

Etter, W. 1988 Financial Feasibility Analysis for Real Estate Development. The Journal of Real Estate Development 4(1):4455. Freeman, R. 1984 Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman. Geltner, D., and N. Miller 2001 Commercial Real Estate Analysis and Investments. Mason: South-Western Publishing. Graaskamp, J. 1970 A Guide to Feasibility Analysis. Chicago: Society of Real Estate Appraisers. Grimble, R., and M.-K. Chan 1995 Stakeholder Analysis for Natural Resource Management in Developing Countries. Natural Resources Forum 19:113124. Grimble, R., and K. Wellard 1997 Stakeholder Methodologies in Natural Resource Management: A Review of Principles, Contexts, Experiences and Opportunities. Agricultural Systems 55:173193. Hardy, A., and R. Beeton 2001 Sustainable Tourism or Maintainable Tourism: Managing Resources for More Than Average Outcomes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 9:168192. Harrison, J., and R. Freeman 1999 Stakeholders, Social Responsibility, and Performance: Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Perspectives. The Academy of Management Journal 42:479485. Hart, S., and G. Ahuja 1998 Does It Pay to be Green? An Empirical Examination of the Relationship Between Emission Reduction and Firm Performance. Business Strategy and the Environment 5:3037. Herremans, I., and C. Welsh 1999 Developing and Implementing a Companys Ecotourism Mission Statement. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 7(1):4876. 2001 Developing and Implementing a Companys Ecotourism Mission Statement: Treadsoftly Revisited. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 9(1):7684. Hofstrand, D., and M. Holz-Clause. 2004 Feasibility Study Outline. <http:// www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/wholefarm/html/c5-66.html>. Ioannides, D. 1995 Planning for International Tourism in Less Developed Countries: Toward Sustainability? Journal of Planning Literature 9:235254. Judge, W., and T. Douglas 1998 Performance Implications of Incorporating Natural Environmental Issues into the Strategic Planning Process: An Empirical Assessment. Journal of Management Studies 35(2):241262. Ladkin, A., and A. Bertramini 2002 Collaborative Tourism Planning: A Case Study of Cusco, Peru. Current Issues in Tourism 5:7193. Lane, M. 2005 Public Participation in Planning: An Intellectual History. Australian Geographer 36:283299. Lyles, M., I. Baird, J. Orris, and D. Kuratko 1993 Formalized Planning in Small Business: Increasing Strategic Choices. Journal of Small Business Management 31:3850. Marcouiller, D. 1997 Towards Integrative Tourism Planning in Rural America. Journal of Planning Literature 11:337357. Matson, J. 2004 The Cooperative Feasibility Study Process. <www.agecon.uga.edu/~gacoops/info34.htm>. Medeiros de Araujo, L., and B. Bramwell 1999 Stakeholder Assessment and Collaborative Tourism Planning: The Case of Brazils Costa Dourada Project. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 7: 356378.

62

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

Miller, C., and L. Cardinal 1994 Strategic Planning and Firm Performance: A Synthesis of More than Two Decades of Research. The Academy of Management Journal 37:16491665. Mitchell, R., B. Agle, and D. Wood 1997 Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identication and Salience: Dening the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Academy of Management Review 22:853886. Murphy, P., and A. Murphy 2004 Strategic Management for Tourism Communities: Bridging the Gaps. Clevedon: Channel View Publications. Myers, M., G. Lawless, and E.G. Nadeau, eds. 1998 Conducting a Feasibility Study. In Cooperatives: A Tool for Community Economic Development (Chap. 5). <http://www.wisc.edu/uwcc/manual/ chap_5.html> Neal, J., and J. Trocke 2002 A Guide for a Feasibility Study of Recreational Enterprises. <http://www.msue.msu.edu/msue/imp/modtd/33119707.html> Pearce, J. II,, E. Freeman, and R. Robinson Jr 1987 The Tenuous Link Between Formal Strategic Planning and Financial Performance. The Academy of Management Review 12:658675. Powell, T. 1992 Strategic Planning as Competitive Advantage. Strategic Management Journal 13:551558. Reilly, M., and N. Millikin 1996 Starting a Small Business: The Feasibility Analysis. Montguide.<http:// www.montana.edu/wwwpb/pubs/mt9510.pdf> Rhyne, L. 1986 The Relationship of Strategic Planning to Financial Performance. Strategic Management Journal 7:423436. Robinson, R. Jr.,, and J. II, Pearce 1983 The Impact of Formalized Strategic Planning on Financial Performance in Small Organizations. Strategic Management Journal 4:197207. Rue, L., and N. Ibrahim 1998 The Relationship Between Planning Sophistication and Performance in Small Businesses. Journal of Small Business Management 36:2433. Ruf, B., K. Muralidhar, R. Brown, J. Janney, and K. Paul 2001 An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship Between Change in Corporate Social Performance and Financial Performance: A Stakeholder Theory Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics 32:143156. Sautter, E., and B. Leisen 1999 Managing Stakeholders: A Tourism Planning Model. Annals of Tourism Research 26:312328. Savage, G., T. Nix, C. Whitehead, and J. Blair 1991 Strategies for Assessing and Managing Organizational Stakeholders. Academy of Management Executive 5(2):5175. Schwenk, C., and C. Shrader 1993 Effects of Formal Strategic Planning on Financial Performance in Small Firms: A Meta-Analysis. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 17:5364. Sheehan, L., and J. Ritchie 2005 Destination Stakeholders Exploring Identity and Salience. Annals of Tourism Research 32:711734. Shen, L., M. Wu, and J. Wang 2002 A Model for Assessing the Feasibility of Construction Project in Contributing to the Attainment of Sustainable Development. Journal of Construction Research 3:255270. Simpson, K. 2001 Strategic Planning and Community Involvement as Contributors to Sustainable Tourism Development. Current Issues in Tourism 4:341.

R.R. Currie et al. / Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2009) 4163

63

Smith, G. 2002 Getting Started in a Recreation or Tourism Business. <http://www.msue. msu.edu/msue/imp/modtd/33510050.html> Soteriou, E., and C. Roberts 1998 The Strategic Planning Process in National Tourism Organizations. Journal of Travel Research 37:2129. Stemler, S. 2001 An Overview of Content Analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 7.<http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=17> The Economic Planning Group of Canada. 2005 A Guide to Starting and Operating an Adventure Tourism Business in Nova Scotia. Halifax: The Province of Nova Scotia. Timothy, D. 1999 Participatory Planning: A View of Tourism in Indonesia. Annals of Tourism Research 26:371391. United Nations World Tourism Organization 2002 Quebec Declaration on Ecotourism. <http://www.world-tourism.org/ sustainable/IYE/quebec_declaration/eng.pdf> 2003 WTO Recommendations to Governments for Supporting and/or Establishing National Certication Systems for Sustainable Tourism. <http:// www.world-tourism.org/sustainable/doc/certication-gov-recomm.pdf> USAID Centre for Development Information and Evaluation 1996 Conducting Key Informant Interviews. Performance Monitoring and Evaluation TIPS. <http://pdf.dec.org/pdf_docs/PNABS541.pdf> Vos, J. 2003 Corporate Social Responsibility and the Identication of Stakeholders. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 10:141152. Welsh, C., and I. Herremans 1998 Treadsoftly: Adopting Environmental Management in the Start-up Phase. Journal of Organizational Change Management 11(2):145156. West, S. 1993 Feasibility Analyses, an Explanation! Cost Engineering 35(3):3543. Winn, M. 2001 Building Stakeholder Theory with a Decision Modeling Methodology. Business and Society 40:133166. Yip, G. 1985 Who Needs Strategic Planning? The Journal of Business Strategy 6(Fall):3041. Yuksel, F., B. Bramwell, and A. Yuksel 1999 Stakeholder Interviews and Tourism Planning at Pamukkale, Turkey. Tourism Management 20:351360.

Submitted 31 May 2007. Resubmitted 1 October 2007. Resubmitted 6 October 2008. Final Version 8 October 2008. Accepted 10 October 2008. Refereed anonymously. Coordinating Editor: Peter Murphy

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

You might also like

- Outdoor Composting Guide 06339 FDocument9 pagesOutdoor Composting Guide 06339 FAdjgnf AANo ratings yet

- GPU Programming in MATLABDocument6 pagesGPU Programming in MATLABkhaardNo ratings yet

- Scenario-Based Strategy Maps (Business Horizons, Vol. 53, Issue 4) (2010)Document13 pagesScenario-Based Strategy Maps (Business Horizons, Vol. 53, Issue 4) (2010)Trí VõNo ratings yet

- Infor Mashup SDK Developers Guide Mashup SDKDocument51 pagesInfor Mashup SDK Developers Guide Mashup SDKGiovanni LeonardiNo ratings yet

- NFPA 99 Risk AssessmentDocument5 pagesNFPA 99 Risk Assessmenttom ohnemusNo ratings yet

- Public RelationsDocument21 pagesPublic RelationsAlbert (Aggrey) Anani-BossmanNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness in Project Portfolio ManagementFrom EverandEffectiveness in Project Portfolio ManagementRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- X Ay TFF XMST 3 N Avx YDocument8 pagesX Ay TFF XMST 3 N Avx YRV SATYANARAYANANo ratings yet

- Strategic Analysis in A Global, Dynamic Business EnvionmentDocument160 pagesStrategic Analysis in A Global, Dynamic Business EnvionmentRiadh RidhaNo ratings yet

- Progress ReportDocument5 pagesProgress Reportapi-394364619No ratings yet

- Forming, Implementing, and Changing StrategiesDocument24 pagesForming, Implementing, and Changing Strategiesananto muhammadNo ratings yet

- A Scenario-Based Approach To Strategic Planning !!!Document45 pagesA Scenario-Based Approach To Strategic Planning !!!apritul3539No ratings yet

- HR PlanningDocument47 pagesHR PlanningPriyanka Joshi0% (1)

- Scenario-Based Strategic Planning WPDocument32 pagesScenario-Based Strategic Planning WPSoledad Perez100% (4)

- Civil Boq AiiapDocument170 pagesCivil Boq AiiapMuhammad ArslanNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning Process Formality andDocument12 pagesStrategic Planning Process Formality andSayid 0ali Cadceed FiidowNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research A N D Implementation Evaluation: A Path To Organizational LearningDocument10 pagesQualitative Research A N D Implementation Evaluation: A Path To Organizational LearningPhan CangNo ratings yet

- 2014.tassabehji e Isherwood-Gestion Uso HEDocument18 pages2014.tassabehji e Isherwood-Gestion Uso HEf_caro01No ratings yet

- Strategic Planning Emphasis and Planning Satisfaction in Small FirmsDocument21 pagesStrategic Planning Emphasis and Planning Satisfaction in Small FirmsAdhi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- ElBana natureandpracticeofSPinEgyptDocument36 pagesElBana natureandpracticeofSPinEgyptAhmed AbomansourNo ratings yet

- Purpose: KeywordsDocument17 pagesPurpose: KeywordsΦώτα ΣαρημιχαηλίδουNo ratings yet

- 1444 Thnarudee Chatchai-209Document15 pages1444 Thnarudee Chatchai-209groupdoyaNo ratings yet

- SCENARIO-BASED STRATEGY MAPSDocument16 pagesSCENARIO-BASED STRATEGY MAPShindrik52No ratings yet

- Khalidiya Mostafa Atta Abd, Iraqi University Sami Ahmed Abbas, Iraqi University Araden Hatim Khudair, University of Al-MustansiriyaDocument11 pagesKhalidiya Mostafa Atta Abd, Iraqi University Sami Ahmed Abbas, Iraqi University Araden Hatim Khudair, University of Al-MustansiriyaFakhira ShehzadiNo ratings yet

- Research Review 1Document4 pagesResearch Review 1jossy100% (1)

- The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future DirectionsDocument22 pagesThe Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directionschirag shahNo ratings yet

- Formal Strategic Planning Operating Environment SiDocument21 pagesFormal Strategic Planning Operating Environment SiSayid 0ali Cadceed FiidowNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Strategy and HR PlanDocument4 pagesRelationship Between Strategy and HR PlanLelouch LamperougeNo ratings yet

- The Role and Importance of Space Matrix in Strategic Business ManagementDocument7 pagesThe Role and Importance of Space Matrix in Strategic Business ManagementNaresh JeyapalanNo ratings yet

- Armstrong - 1982 - The Value of Formal Planning For Strategic Decisions Review of Empirical ResearchDocument17 pagesArmstrong - 1982 - The Value of Formal Planning For Strategic Decisions Review of Empirical ResearchEllen Luisa PatolaNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Strategic Management Tools and TechniquesDocument16 pagesTop 10 Strategic Management Tools and TechniquesVerika RahayuNo ratings yet

- Pinto1990 PDFDocument23 pagesPinto1990 PDFAastha ShahNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Decision, Environmental and Firm Characteristics On The Rationality of Strategic Decision-Making - Elbanna - 2007 - Journal of Management Studies - Wiley Online LibraryDocument51 pagesThe Influence of Decision, Environmental and Firm Characteristics On The Rationality of Strategic Decision-Making - Elbanna - 2007 - Journal of Management Studies - Wiley Online LibraryburiggNo ratings yet

- 16182-57309-1-PB 1 PDFDocument15 pages16182-57309-1-PB 1 PDFHaritKulkarniNo ratings yet

- Evaluatin G Projects: H00141539 - Project Economics and Evaluation 1Document15 pagesEvaluatin G Projects: H00141539 - Project Economics and Evaluation 1Mustafa RokeryaNo ratings yet

- O'Regan, N. C.S. PaperDocument35 pagesO'Regan, N. C.S. PaperAli HaddadouNo ratings yet

- A New Approach To Linking Strategy Formulation and Strategy Implementation An Example From The UK Banking SectorDocument18 pagesA New Approach To Linking Strategy Formulation and Strategy Implementation An Example From The UK Banking SectorInni Daaotu JiharanNo ratings yet

- Strategic Tools and Techniques in PracticeDocument26 pagesStrategic Tools and Techniques in PracticeVivek KotakNo ratings yet

- A Framework To Implement Strategies in OrganizationsDocument12 pagesA Framework To Implement Strategies in OrganizationsBhanu PrakashNo ratings yet

- The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard As A Framework For Eco-Efficiency AnalysisDocument11 pagesThe Sustainability Balanced Scorecard As A Framework For Eco-Efficiency AnalysisphilirlNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning Impacts University of Uyo PerformanceDocument17 pagesStrategic Planning Impacts University of Uyo PerformancesamutechNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kelompok 2Document17 pagesJurnal Kelompok 2priagunghudaNo ratings yet

- 1997 - MOSHE FARJOUN - SIMILARITYJUDGMENTSINSTRATEGYFORMULATIONROLEPROCESretrieved 2017-10-15Document20 pages1997 - MOSHE FARJOUN - SIMILARITYJUDGMENTSINSTRATEGYFORMULATIONROLEPROCESretrieved 2017-10-15osama1996meNo ratings yet

- Berkhout Foresight PDFDocument16 pagesBerkhout Foresight PDFMiranda081No ratings yet

- Impact of Strategic Alignment On Organizational Performance PDFDocument22 pagesImpact of Strategic Alignment On Organizational Performance PDFSitara QadirNo ratings yet

- A Scenario-Based Approach To Strategic Planning - Integrating Planning and Process Perspective of StrategyDocument41 pagesA Scenario-Based Approach To Strategic Planning - Integrating Planning and Process Perspective of StrategyIvana IlicNo ratings yet

- Importance and Behavior of Capital Project Benefits Factors in Practice: Early EvidenceDocument13 pagesImportance and Behavior of Capital Project Benefits Factors in Practice: Early EvidencevimalnandiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3 (17sep13)Document64 pagesLecture 3 (17sep13)Ifzal AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Strategic Planning On Organizational Performance Through Strategy ImplementationDocument7 pagesThe Impact of Strategic Planning On Organizational Performance Through Strategy ImplementationSasha KingNo ratings yet

- The Measurement of Strategic Orientation and Its Efficacy in Predicting Financial PerformanceDocument21 pagesThe Measurement of Strategic Orientation and Its Efficacy in Predicting Financial PerformanceDwitya AribawaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning Process and Company PerformanceDocument40 pagesStrategic Planning Process and Company PerformanceAlazer Tesfaye Ersasu TesfayeNo ratings yet

- A Contingency Model of The Association B PDFDocument18 pagesA Contingency Model of The Association B PDFrizal galangNo ratings yet

- Competitive Strategic Maneuverability: The Missing Link Between Strategic Planning and Firm's PerformanceDocument10 pagesCompetitive Strategic Maneuverability: The Missing Link Between Strategic Planning and Firm's PerformancehermasdtpNo ratings yet

- Academy of ManagementDocument13 pagesAcademy of ManagementMichelle LeeNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Budgeting and Financial Management Practices of District Health Directorates in GhanaDocument16 pagesFactors Affecting Budgeting and Financial Management Practices of District Health Directorates in GhanaMinsar PagalaNo ratings yet

- Stratgeic TypeDocument20 pagesStratgeic TypeAndreas Putra SanjayaNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Rooke - Developing - and - Implementing - A - Strategy - For - Benefits - RealisationDocument11 pages2010 - Rooke - Developing - and - Implementing - A - Strategy - For - Benefits - RealisationCarlos BocanegraNo ratings yet

- The Marketing Planning Process PDFDocument12 pagesThe Marketing Planning Process PDFBellphawineesiriNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning Process To Company PeDocument47 pagesStrategic Planning Process To Company PeNigus AyeleNo ratings yet

- 4 - Strategic Planning in A Turbulent Environment - Evidence From The Oil Majors - SMJ, 2003 - GrantDocument28 pages4 - Strategic Planning in A Turbulent Environment - Evidence From The Oil Majors - SMJ, 2003 - GrantNdèye Seyni DiakhatéNo ratings yet

- Strategy Development, Planning and Performance - A Case Study of The Finnish PoliceDocument17 pagesStrategy Development, Planning and Performance - A Case Study of The Finnish Policeamer DanounNo ratings yet