Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Greek Triumvirate

Uploaded by

GeneOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Greek Triumvirate

Uploaded by

GeneCopyright:

Available Formats

The Greek Triumvirate 1.

Socrates

Socrates was a Greek philosopher, born in Athens in 469 B.C., whose beliefs were a great influence on philosophy. He started his early life as an apprentice for his father, a sculptor, and practiced it for several years, prior to giving nearly all of his time to intellectual pursuits. Socrates, himself, wrote nothing, and our knowledge of his ideas is reliant on the writings of Xenophon, Aristophanes, and most of all, Plato. His relentless dedication to philosophy profoundly affected his contemporaries, and, because of what we have learned through Plato, on resultant philosophy. Plato's interpretation of Socrates, however, is partially his own formation. However, it is feasible to determine certain ideas that are truly from Socrates. He searched for definitions of words, wondering, "What is justice?" and, "What is courage?" for example. Without them, he believed, true wisdom would not be achievable. He had his own formula of questions and answers to grasp the definitions. Socrates wondered if goodness, like the sophists thought, would be learned. He felt that there was a connection between goodness and knowledge of what is good, and so, he thought that anyone who achieved that knowledge could not purposely act badly. All of Socrates' intellectual study was precisely for attaining happiness in life by living the right way. Not surprisingly, Socrates' ideas made him quite unpopular with other townspeople. He made the conclusion that intellect embodied the knowledge of one's own ignorance and believed that others simply were not aware of their own. What we now refer to as the "Socratic method" of philosophical questioning included questioning people on their affirmed positions and helping them to question themselves to the point of outright contradictions, which would prove each one's own ignorance. The Socratic method gave birth to dialectic, the belief that truth must be approached by changing one's position by questioning and exposing them to contrary beliefs. One thing that Socrates affirmed to have knowledge of was "the art of love." He connected this concept with that of the "love of wisdom," or philosophy. He never straight out declared to be wise, he just claimed to understand the way a lover of wisdom must go to aspire to it. Although he claimed extreme loyalty to Athens, Socrates' obligation to the truth and the quest of virtue conflicted with the current policies and society of the city. His offenses were that he was a moral and social critic and tried to weaken the common concept of "might makes right" there at the time. he was found guilty of corrupting Athens' youth, and his sentence was to drink a poisonous mix. Plato and Xenophon both claimed that Socrates would have had a chance to escape by fleeing from Athens after his followers bribed the prison guards. Although, he chose not to do so because he believed it would show he had a fear of death, which he believed no philosopher has and that even if he chose to leave, his thought teachings would not fare better in a different country. He also may have subjected himself to being accused of crimes by the citizens and

proven guilty by a jury. This would have caused him to break "contract" with the state, and thus go against Socratic principle. Socrates Contribution to Philosophy Perhaps his most important contribution to Western thought is his dialectic method of inquiry, known as the Socratic method or method of "elenchus", which he largely applied to the examination of key moral concepts such as the Good and Justice. It was first described by Plato in the Socratic Dialogues. To solve a problem, it would be broken down into a series of questions, the answers to which gradually distill the answer a person would seek. The influence of this approach is most strongly felt today in the use of the scientific method, in which hypothesis is the first stage. The development and practice of this method is one of Socrates' most enduring contributions, and is a key factor in earning his mantle as the father of political philosophy, ethics or moral philosophy, and as a figurehead of all the central themes in Western philosophy. To illustrate the use of the Socratic method; a series of questions are posed to help a person or group to determine their underlying beliefs and the extent of their knowledge. The Socratic method is a negative method of hypothesis elimination, in that better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. It was designed to force one to examine one's own beliefs and the validity of such beliefs. In fact, Socrates once said, "I know you won't believe me, but the highest form of Human Excellence is to question oneself and others." An alternative interpretation of the dialectic is that it is a method for direct perception of the Form of the Good. Philosopher Karl Popper describes the dialectic as "the art of intellectual intuition, of visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances." In a similar vein French philosopher Pierre Hadot suggests that the dialogues are a type of spiritual exercise. "Furthermore," writes Hadot, "in Plato's view, every dialectical exercise, precisely because it is an exercise of pure thought, subject to the demands of the Logos, turns the soul away from the sensible world, and allows it to convert itself towards the Good."

2. Aristotle

Aristotle was born at Stageira, a colony of Andros on the Macedonian peninsula Chalcidice in 384 BC. His father, Nicomachus, was court physician to King Amyntas III of Macedon. It is believed that Aristotle's ancestors held this position under various kings of Macedonia. As such, Aristotle's early education would probably have consisted of instruction in medicine and biology from his father. About his mother, Phaestis, little is known. It is known that she died early in Aristotle's life. When Nicomachus also died, in Aristotle's tenth year, he was left an orphan and placed under the guardianship of his uncle, Proxenus of Atarneus. He taught Aristotle Greek, rhetoric, and poetry (O'Connor et al., 2004). Aristotle was probably influenced by his father's medical knowledge; when he went to Athens at the age of 18, he was likely

already trained in the investigation of natural phenomena. From the ages of 18 to 37 Aristotle remained in Athens as a pupil of Plato and distinguished himself at the Academe. The relations between Plato and Aristotle have formed the subject of various legends, many of which depict Aristotle unfavourably. No doubt there were divergences of opinion between Plato, who took his stand on sublime, idealistic principles, and Aristotle, who even at that time showed a preference for the investigation of the facts and laws of the physical world. It is also probable that Plato suggested that Aristotle needed restraining rather than encouragement, but not that there was an open breach of friendship. In fact, Aristotle's conduct after the death of Plato, his continued association with Xenocrates and other Platonists, and his allusions in his writings to Plato's doctrines prove that while there were conflicts of opinion between Plato and Aristotle, there was no lack of cordial appreciation or mutual forbearance. Besides this, the legends that reflect Aristotle unfavourably are traceable to the Epicureans, who were known as slanderers. If such legends were circulated widely by patristic writers such as Justin Martyr and Gregory Nazianzen, the reason lies in the exaggerated esteem Aristotle was held in by the early Christian heretics, not in any well-grounded historical tradition. Aristotle as philosopher and tutor After the death of Plato (347 BC), Aristotle was considered as the next head of the Academe, a post that was eventually awarded to Plato's nephew. Aristotle then went with Xenocrates to the court of Hermias, ruler of Atarneus in Asia Minor, and married his niece and adopted daughter, Pythia. In 344 BC, Hermias was murdered in a rebellion (or a Persian attack?), and Aristotle went with his family to Mytilene. It is also reported that he stopped on Lesbos and briefly conducted biological research. Then, one or two years later, he was summoned to his native Stageira by King Philip II of Macedon to become the tutor of Alexander the Great, who was then 13. Plutarch wrote that Aristotle not only imparted to Alexander a knowledge of ethics and politics, but also of the most profound secrets of philosophy. We have much proof that Alexander profited by contact with the philosopher, and that Aristotle made prudent and beneficial use of his influence over the young prince (although Bertrand Russell disputes this). Due to this influence, Alexander provided Aristotle with ample means for the acquisition of books and the pursuit of his scientific investigation. According to sources such as Plutarch and Diogenes, Philip had Aristotle's hometown of Stageira burned during the 340s BC, and Aristotle successfully requested that Alexander rebuild it. During his tutorship of Alexander, Aristotle was reportedly considered a second time for leadership of the Academy; his companion Xenocrates was selected instead. Founder and master of the Lyceum In about 335 BC, Alexander departed for his Asiatic campaign, and Aristotle, who had served as an informal adviser (more or less) since Alexander ascended

the Macedonian throne, returned to Athens and opened his own school of philosophy. He may, as Aulus Gellius says, have conducted a school of rhetoric during his former residence in Athens; but now, following Plato's example, he gave regular instruction in philosophy in a gymnasium dedicated to Apollo Lyceios, from which his school has come to be known as the Lyceum. (It was also called the Peripatetic School because Aristotle preferred to discuss problems of philosophy with his pupils while walking up and down -peripateo -- the shaded walks -- peripatoi -- around the gymnasium.) During the thirteen years (335 BC322 BC) which he spent as teacher of the Lyceum, Aristotle composed most of his writings. Imitating Plato, he wrote "Dialogues" in which his doctrines were expounded in somewhat popular language. He also composed the several treatises (which will be mentioned below) on physics, metaphysics, and so forth, in which the exposition is more didactic and the language more technical than in the "Dialogues". These writings show to what good use he put the resources Alexander had provided for him. They show particularly how he succeeded in bringing together the works of his predecessors in Greek philosophy, and how he pursued, either personally or through others, his investigations in the realm of natural phenomena. Pliny claimed that Alexander placed under Aristotle's orders all the hunters, fishermen, and fowlers of the royal kingdom and all the overseers of the royal forests, lakes, ponds and cattle-ranges, and Aristotle's works on zoology make this statement more believeable. Aristotle was fully informed about the doctrines of his predecessors, and Strabo asserted that he was the first to accumulate a great library. During the last years of Aristotle's life the relations between him and Alexander the Great became very strained, owing to the disgrace and punishment of Callisthenes whom Aristotle had recommended to Alexander. Nevertheless, Aristotle continued to be regarded at Athens as a friend of Alexander and a representative of Macedonia. Consequently, when Alexander's death became known in Athens, and the outbreak occurred which led to the Lamian war, Aristotle shared in the general unpopularity of the Macedonians. The charge of impiety, which had been brought against Anaxagoras and Socrates, was now, with even less reason, brought against Aristotle. He left the city, saying (according to many ancient authorities) that he would not give the Athenians a chance to sin a third time against philosophy. He took up residence at his country house at Chalcis, in Euboea, and there he died the following year, 322 BC. His death was due to a disease, reportedly 'of the stomach', from which he had long suffered. The story that his death was due to hemlock poisoning, as well as the legend that he threw himself into the sea "because he could not explain the tides," is without historical foundation. Very little is known about Aristotle's personal appearance except from hostile sources. The statues and busts of Aristotle, possibly from the first years of the Peripatetic School, represent him as sharp and keen of countenance, and somewhat below the average height. His characteras revealed by his writings, his will (which is undoubtedly genuine), fragments of his letters and the allusions of his unprejudiced contemporarieswas that of a high-minded, kind-hearted man, devoted to his family and his friends, kind to his slaves, fair to his enemies and rivals, grateful towards his

benefactors. When Platonism ceased to dominate the world of Christian speculation, and the works of Aristotle began to be studied without fear and prejudice, the personality of Aristotle appeared to the Christian writers of the 13th century, as it had to the unprejudiced pagan writers of his own day, as calm, majestic, untroubled by passion, and undimmed by any great moral defects, "the master of those who know".

You might also like

- Sakolsky Ron Seizing AirwavesDocument219 pagesSakolsky Ron Seizing AirwavesPalin WonNo ratings yet

- Operations Management Success FactorsDocument147 pagesOperations Management Success Factorsabishakekoul100% (1)

- Internal Credit Risk Rating Model by Badar-E-MunirDocument53 pagesInternal Credit Risk Rating Model by Badar-E-Munirsimone333No ratings yet

- Budokon - Mma.program 2012 13Document10 pagesBudokon - Mma.program 2012 13Emilio DiazNo ratings yet

- Nature vs Nurture: How Genetics and Parenting Shape Social DevelopmentDocument3 pagesNature vs Nurture: How Genetics and Parenting Shape Social DevelopmentJohn Roland Faegane Peji100% (1)

- Unit 1 Topic 1 Philosophical PerspectiveDocument51 pagesUnit 1 Topic 1 Philosophical PerspectivePau AbuenaNo ratings yet

- Management Advisory ServicesDocument7 pagesManagement Advisory ServicesMarc Al Francis Jacob40% (5)

- Basic Statistical Tools for Data Analysis and Quality EvaluationDocument45 pagesBasic Statistical Tools for Data Analysis and Quality EvaluationfarjanaNo ratings yet

- Linux OS MyanmarDocument75 pagesLinux OS Myanmarweenyin100% (15)

- RenaissanceDocument3 pagesRenaissanceInactive Main PageNo ratings yet

- Ashforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The OrganizationDocument21 pagesAshforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The Organizationhoorie100% (1)

- Sucesos de Las Islas FilipinasDocument1 pageSucesos de Las Islas FilipinasMaxine TaeyeonNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Self QuizDocument3 pagesUnderstanding The Self QuizAngelibeth Pado NopiaNo ratings yet

- Defining BeautyDocument5 pagesDefining BeautyEllen VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs TheoryDocument8 pagesMaslow's Hierarchy of Needs TheoryKenNo ratings yet

- The 5 Statements that Inspired MeDocument14 pagesThe 5 Statements that Inspired Mesenior highNo ratings yet

- PhilosopherDocument3 pagesPhilosopherAlthia EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- IV Martial Law PeriodDocument5 pagesIV Martial Law PeriodAnthony0% (1)

- Human Rights and Dignity ExplainedDocument2 pagesHuman Rights and Dignity ExplainedDivine Mae Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Introduction To History: Definition, Issues, Sources, and MethodologyDocument15 pagesIntroduction To History: Definition, Issues, Sources, and MethodologyGerald LegesnianaNo ratings yet

- (UTS) Perspectives - PhilosophyDocument10 pages(UTS) Perspectives - PhilosophyAlyssa Crizel CalotesNo ratings yet

- 01 Philippine Fiesta and Colonial CultureDocument22 pages01 Philippine Fiesta and Colonial CultureTherese Sarmiento100% (1)

- Module 4 Activity1&2 (Freedom and Responsibility, A Clockwork Orange)Document9 pagesModule 4 Activity1&2 (Freedom and Responsibility, A Clockwork Orange)Znyx Aleli Jazmin-MarianoNo ratings yet

- Ge Uts Activity 2Document2 pagesGe Uts Activity 2Ronna Mae DungogNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document3 pagesLesson 1Jesslee Edaño TaguiamNo ratings yet

- BrochureDocument2 pagesBrochureCarlo DimarananNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 The Self in The Western Eastern Oriental ThoughtDocument4 pagesLesson 5 The Self in The Western Eastern Oriental ThoughtMary Joy CuetoNo ratings yet

- Week 7 RizalDocument6 pagesWeek 7 RizalShervee PabalateNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Beliefs of The Early FilipinosDocument13 pagesSpiritual Beliefs of The Early FilipinosJan Bryan GuiruelaNo ratings yet

- Folk Dances of The PhilippineDocument9 pagesFolk Dances of The PhilippineLizette PiñeraNo ratings yet

- Political Dimension of Globalization: The Changing Role of Nation-StatesDocument3 pagesPolitical Dimension of Globalization: The Changing Role of Nation-StatesKyle Hyden ManaloNo ratings yet

- GE 5 Lesson 1Document2 pagesGE 5 Lesson 1Angelica AbogandaNo ratings yet

- III. Group Structure and CommunicationDocument19 pagesIII. Group Structure and CommunicationRonn Serrano100% (1)

- NSTP Law: Key Concepts and GuidelinesDocument4 pagesNSTP Law: Key Concepts and GuidelinesAzzam AmpuanNo ratings yet

- Communication and GlobalizationDocument6 pagesCommunication and GlobalizationPaopao MacalaladNo ratings yet

- The Study of Political ScienceDocument7 pagesThe Study of Political ScienceAljon MalotNo ratings yet

- Global Citizen Essay Edgar CDocument2 pagesGlobal Citizen Essay Edgar Capi-353368377No ratings yet

- Japan, Industrial Giant of Asia: Geography. The Japanese Call Their Nation Nippon, Which Means "Land of The RisingDocument15 pagesJapan, Industrial Giant of Asia: Geography. The Japanese Call Their Nation Nippon, Which Means "Land of The RisingJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Readings in Philippine History - Understanding History Chapter III Notes (L. Gottschalk, 1969)Document6 pagesReadings in Philippine History - Understanding History Chapter III Notes (L. Gottschalk, 1969)collegestudent2000No ratings yet

- View of The Self: Philosophical PerspectivesDocument30 pagesView of The Self: Philosophical PerspectivesGeneral BorjaNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Development: A NarrationDocument6 pagesChild and Adolescent Development: A NarrationLeowens VenturaNo ratings yet

- The Komisyon Sa Wikang Filipino Was The First To Issue A Statement Endorsing MotherDocument9 pagesThe Komisyon Sa Wikang Filipino Was The First To Issue A Statement Endorsing MotherSarah BaylonNo ratings yet

- Philosophies in Life of RIZALDocument4 pagesPhilosophies in Life of RIZALFel FrescoNo ratings yet

- Is The World Becoming More Homogeneous?Document4 pagesIs The World Becoming More Homogeneous?Duane EdwardsNo ratings yet

- TelosDocument1 pageTelosPascual Limuel GolosinoNo ratings yet

- Establishing A Democratic CultureDocument9 pagesEstablishing A Democratic CultureGabriel GimeNo ratings yet

- Political SelfDocument8 pagesPolitical SelfFRANC MELAN TANAY LANDONGNo ratings yet

- Content vs Context: Which is More ImportantDocument17 pagesContent vs Context: Which is More ImportantCarlos Baul DavidNo ratings yet

- Delving On The Philosophies of Emilio JacintoDocument1 pageDelving On The Philosophies of Emilio JacintoLovelle Marie Role100% (1)

- The Hindu View of ManDocument7 pagesThe Hindu View of Manphils_skoreaNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Assessment QuizDocument2 pagesModule 3 Assessment QuizAva DoveNo ratings yet

- Technology As A Way of RevealingDocument4 pagesTechnology As A Way of RevealingGeemaica MacaraigNo ratings yet

- Discover Your Physical SelfDocument34 pagesDiscover Your Physical SelfAnna Jean Tejada - CapillanNo ratings yet

- CFC - Chapter 03Document11 pagesCFC - Chapter 03irish xNo ratings yet

- Understanding HistoryDocument9 pagesUnderstanding HistorySinful ShiroeNo ratings yet

- CST ReviewerDocument8 pagesCST Reviewerjasmin libatogNo ratings yet

- Lts ProjectDocument12 pagesLts Projectdaren vicenteNo ratings yet

- ConfucianismDocument22 pagesConfucianismNianna Aleksei Petrova100% (3)

- Sacred Text BuddhismDocument12 pagesSacred Text BuddhismJay KotakNo ratings yet

- Uts 3Document2 pagesUts 3Neill Antonio AbuelNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Philosophy Group-7Document19 pagesLinguistic Philosophy Group-7Alwin AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 UtsDocument3 pagesLesson 3 UtsJohnpert Toledo100% (1)

- NSTP CWTS ModuleDocument42 pagesNSTP CWTS ModuleTrisha Anne Aica RiveraNo ratings yet

- Eustress FinallyDocument13 pagesEustress FinallysiyanvNo ratings yet

- 3 Anthropological Conceptualization of SelfDocument2 pages3 Anthropological Conceptualization of SelfMicsjadeCastilloNo ratings yet

- Modern PhilosophiesDocument6 pagesModern PhilosophiesGLENNYFER GERVACIONo ratings yet

- CarpentryDocument2 pagesCarpentryGeneNo ratings yet

- Fluids PresentationDocument4 pagesFluids PresentationGeneNo ratings yet

- Project Schedule2Document2 pagesProject Schedule2GeneNo ratings yet

- Note PadDocument2 pagesNote PadGeneNo ratings yet

- Bluetooth Mobile Based College CampusDocument12 pagesBluetooth Mobile Based College CampusPruthviraj NayakNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Consumer BehaviourDocument16 pagesDeterminants of Consumer BehaviouritistysondogNo ratings yet

- Hitachi Loader Lx70 Lx80 Service Manual KM 111 00yyy FTT HDocument22 pagesHitachi Loader Lx70 Lx80 Service Manual KM 111 00yyy FTT Hmarymurphy140886wdi100% (103)

- Senator Frank R Lautenberg 003Document356 pagesSenator Frank R Lautenberg 003Joey WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Automatic Night LampDocument22 pagesAutomatic Night LampAryan SheoranNo ratings yet

- How To Create A MetacogDocument6 pagesHow To Create A Metacogdocumentos lleserNo ratings yet

- Bunga Refira - 1830104008 - Allophonic RulesDocument6 pagesBunga Refira - 1830104008 - Allophonic RulesBunga RefiraNo ratings yet

- Sample File: Official Game AccessoryDocument6 pagesSample File: Official Game AccessoryJose L GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Second Periodic Test - 2018-2019Document21 pagesSecond Periodic Test - 2018-2019JUVELYN BELLITANo ratings yet

- Unit Revision-Integrated Systems For Business EnterprisesDocument8 pagesUnit Revision-Integrated Systems For Business EnterprisesAbby JiangNo ratings yet

- Indian Archaeology 1967 - 68 PDFDocument69 pagesIndian Archaeology 1967 - 68 PDFATHMANATHANNo ratings yet

- Class 7 CitationDocument9 pagesClass 7 Citationapi-3697538No ratings yet

- SAP HANA Analytics Training at MAJUDocument1 pageSAP HANA Analytics Training at MAJUXINo ratings yet

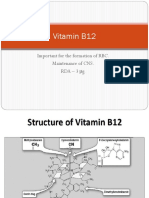

- Vitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceDocument19 pagesVitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceHari PrasathNo ratings yet

- Aviation Case StudyDocument6 pagesAviation Case Studynabil sayedNo ratings yet

- Graphic Design Review Paper on Pop Art MovementDocument16 pagesGraphic Design Review Paper on Pop Art MovementFathan25 Tanzilal AziziNo ratings yet

- GUIA REPASO 8° BÁSICO INGLÉS (Unidades 1-2)Document4 pagesGUIA REPASO 8° BÁSICO INGLÉS (Unidades 1-2)Anonymous lBA5lD100% (1)

- Assignment Chemical Bonding JH Sir-4163 PDFDocument70 pagesAssignment Chemical Bonding JH Sir-4163 PDFAkhilesh AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Experiment 5 ADHAVANDocument29 pagesExperiment 5 ADHAVANManoj Raj RajNo ratings yet

- Needs and Language Goals of Students, Creating Learning Environments andDocument3 pagesNeeds and Language Goals of Students, Creating Learning Environments andapi-316528766No ratings yet

- p240 MemristorDocument5 pagesp240 MemristorGopi ChannagiriNo ratings yet

- Wound Healing (BOOK 71P)Document71 pagesWound Healing (BOOK 71P)Ahmed KhairyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Notes and ReiewDocument6 pagesChapter 1 Notes and ReiewTricia Mae Comia AtienzaNo ratings yet