Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FT (Financial Times) Indian Infrastructure 2009

Uploaded by

Archana MisraOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FT (Financial Times) Indian Infrastructure 2009

Uploaded by

Archana MisraCopyright:

Available Formats

INDIAN INFRASTRUCTURE

A SPECIAL REPORT www.ft.com/indiainfrastructure2009

A critical bottleneck in road to growth

Transport and power plants are high on the agenda for the new government, writes James Lamont

erminal 3 at Indira Gandhi International Airport in New Delhi is one of the most potent signs of a changing India. Over the past months, travellers have witnessed its cavernous steel and concrete interior and then its monumental glass plated frontage rise out of the dust. Within its lofty halls, teams of contractors are working round the clock, placing marble floor tiles, installing baggage conveyer belts and readying aerobridges. GMR, the Bangalorebased infrastructure company building the airport, has a starting pistol as a deadline. In a few months, the helmeted workmen are to be replaced by athletes arriving for the Commonwealth Games in Indias capital. By then, the airports capacity will have risen to 60m passengers a year, it will match international standards of efficiency and have a metro link to business district, Connaught Place and the city centre. Unlike many Indian infrastructure projects, GMRs managers are expecting to deliver the project within time and budget. Delhis new airport build-

ings, and the breathtaking Bandra-Worli Sea Link in Mumbai, the countrys financial capital, are two of the clearest examples that infrastructure development has becomea top priority. They are a hint of the leap that India might make in terms of productivity if it fixes its overburdened, old fashioned and investmentstarved physical infrastructure. Manmohan Singh, the prime minister and a respected development economist, has clearly identified better roads, power plants and ports as important priorities for his newly re-elected Congress partyled government and is directing public spending to the sector. Last month, he told the US-India Business Council in Washington about his ambitions to free up what he considers a debilitating choke-point in the development of Asias third largest economy. Hard infrastructure remains a critical bottleneck in our aspiration to achieve 9 per cent growth, he told US executives. Mr Singhs economic planners are funnelling public spending to the sector and are at pains to modernise the policy and regulatory framework. They view infrastructure spending as a vital part of fiscal stimulus measures to combat the effects of the global economic downturn and keep the country on track for high economic growth. Even before last years financial crisis, the govern-

ment planned for $500bn in infrastructure spending between 2007 and 2012. As a percentage of gross domestic product,it is expected to rise to 9 per cent by 2012, from 5 per cent earlier. The ability to finance infrastructure through the budget is limited, given the many other demands on budgetary resources, says Montek Singh Ahluwalia, the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission and a close adviser to the premier. He says: It is expected that only 70 per cent of needs can be met from public resources. The remaining 30 per cent will have to come from private investment in various forms, including public private partnership. Like many Asian economies, India is trying to attract more private investment into infrastructure. Opinion is divided about its likely volume and targets. While some, including McKinsey, the management consultants, warn of a large funding gap and delays, other individuals, such as Conor McCoole, head of project finance in Asia, for Standard Chartered bank, argue there is no shortage of liquidity for projects in the wake of the global financial crisis. He says larger concerns surround implementation and the expertise to encourage private and public entities to work together harmoniously. Some of the big projects include the $50bn Delhi-

The recently opened BandraWorli Sea Link in Mumbai provides one clear physical example of new emphasis on infrastructure development

Reuters

Mumbai industrial corridor, high-speed rail links between main cities, improved cargo handling at ports and new airport facilities. Highways are also receiving renewed attention. The appointment of Kamal Nath, a former commerce minister, as the minister of road transport and highways has brought energy to the task of attracting investment and expertise to roll out road building across the country. He immediately turned heads by announcing a target of building 20km of road a day in an area of civil engineering that had made almost no progress over the past five years.

But the size of the challenge in a country of 1.2bn people is daunting. Decades of underinvestment have left the country crippled by a severe infrastructure deficit that greatly impedes its ability to sustain high growth rates and alleviate poverty. Roads in the main cities are frequently gridlocked; in rural areas they have crumbled away. Ports are close to capacity, while nuclear power stations, short of fuel, run under capacity. Cities, which in other parts of Asia have helped spur growth, are often devoid of planning in India. Only a quarter of Indias 88 cities with populations of more than 500,000 have formal transport systems, according to the Asian Development Bank. Some economists and investment analysts say that, if physical infrastructure were improved, the country's entrepreneurial drive would comfortably propel it to double-digit growth to rival China's. But in the short term, concerns abound about whether the economy has the capacity to absorb such large spending, a shortage of skills, and the impact a wave of building will have

on the countrys rich biodiversity. Worries over finance and a lagging policy framework have been highlighted by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry. The task of mobilising spending in the coming years, it says, is badly hampered by limited long-term finance, a shallow bond market and constraints on

No agenda for building a new India can any longer be imposed from Delhi . . . India lives in the states

external commercial borrowing. The business lobby group, among others, promotes financial reform to free capital, attract investors such as mutual and pension funds, and overseas infrastructure funds and introduce mechanisms to facilitate investment. Slow implementation, corruption and lethargy in awarding and approving projects also need to be remedied. McKinsey says that India

does not compare favourably with other countries in executing projects, suffering hefty time and cost overruns. Its report Building India: Accelerating Infrastructure Projects drew the comparison that building a thermal power plant in India took three and a half years, while in China it took a year less. Such concerns cast doubt on the speed with which the economy can be transformed by big spending on infrastructure. Parvesh Minocha, managing director of the transport division of Feedback Ventures, a Delhi-based infrastructure consultancy, agrees that delivery will trail ambition, but insists that more is being done now in some areas than in the past 50 years. He says the government needs to take bold steps to recruit project management expertise from abroad to help rebuild India. The $500bn figure may not happen. About 60-70 per cent of it may happen. More like $300bn will happen, he says. But that is still a lot of billions. India will look very different in 10 years from now. Its already looking very different. Robert Zoellick, the presi-

dent of the World Bank, highlights national highways, rural roads, railways and water resources as some of the multilateral lenders top infrastructure projects in India. But he also urges the government to pay more attention to urban development. Much of politics is on rural development needs, Mr Zoellick told the Financial Times. This goes back to [Mahatma] Gandhi. The real challenge is that urbanisation is moving so fast but the ability to deal with it is complicated by the lack of decentralised authority at municipal levels, he says. Mr Singh is mindful of this. India cannot be built from Delhi alone, he warns. With the growth of the market economy and with individual talent and enterprise being unleashed, no agenda for building a new India can any longer be imposed from Delhi . . . India lives in the states. As the steel and glass facades go up at Indira Gandhi International to greet the English-speaking worlds athletes, similar progress needs to take place in hundreds of cities for talk of Indias economic promise to become fact.

Red tape stif les development

LAND

Legal challenges and inaccurate records can make acquisition tortuous, says Amy Kazmin

Five years ago, Reliance Power, owned by billionaire tycoon Anil Ambani, acquired 2,500 acres of farmland on the outskirts of New Delhi, the capital, to build a 7,480 megawatt gasfired power station. The acquisition was facilitated by the government of the state of Uttar Pradesh, which invoked emergency powers to help secure the land quickly. But about 200 farmers, the owners of 400 acres of the land, challenged the forced sale in court. This month, the Allahabad High Court ruled in the farmers favour, finding state officials acted improperly by failing to conduct public hearings to allow the affected landowners to voice objections to the sale. The judges said the power plant could not be considered a public purpose. They ordered state authorities to reopen the process, allow disgruntled farmers to return the money, reclaim their land, and register their objections to the sale. The December 4 judgment said that in cases of largescale acquisition of agricultural land, there had to be a very good reason for dispensing with an inquiry into the interests of the farmers involved. Reliance Power insists

the pronouncement is not a serious setback for the massive project, which is already bogged down in a far bigger dispute with companies owned by Anils elder brother and bitter business rival, Mukesh Ambani, over pricing of natural gas. Yet it highlights one of the biggest obstacles to infrastructure development in India: the contentiousness and complexity of land acquisition in a country where nearly 70 per cent of the population is still rural, and dependent on farmland for their livelihood. Vinayak Chatterjee, the chair of Feedback Ventures, an infrastructure consultancy, says 70 per cent of delays in the countrys highway building program stem from difficulties both in acquiring land and then obtaining permissions to use it for the intended purpose. Other types of projects, including power plants, face similar hurdles. The problem is acute, says Mr Chatterjee, who also serves as chair of the National Council on Infrastructure of the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). It is the complexity of dealing with multiple agencies to do whatever you want to, including the removal of utilities and other obstacles. Land acquisition law allows state authorities to buy farmland for a fair compensation and transfer it to private companies, for projects that are deemed to have a public purpose. In reality, the process is often volatile and highly politicised, especially if opposition politicians throw

their weight behind disgruntled farmers, who believe they have been given a raw deal. Tata Motors decision last year to withdraw from a new car factory in West Bengal after heated protests from farmers alarmed many infrastructure project developers. That has become like a red light for a lot of people, who have paused to look at the way things are in India, says Sunand Sharma, country president of Alstom, which supplies power generation equip-

It is the states responsibility to zone land for the economic development of the country

ment and builds turn-key power plants and other infrastructure projects, for private companies and the public sector. What troubles us is the potential for delay. The court system also allows for protracted legal challenges, exacerbating unpredictability. Further adding to the complexity is the lack of accurate land title records, which means that every piece of property may have multiple parties claiming ownership. India is trying to introduce a law to replace its current land acquisition act, which dates back to the British colonial era. In theory, the new law will allow the state to use its power of eminent

domain to acquire all necessary land for infrastructure projects. But Mr Chatterjee says there are still concerns about the possibility of disputes and protracted delays. Provisions of the bill dont really say how problems on the ground are going to be resolved, he said. The CII believes the government should carry out an extensive survey of the country, identify the most fertile and productive agricultural land to be protected, and then carry out a massive zoning plan, designating certain areas for different types of development, including infrastructure. However, the new land bill makes no provision for any such an undertaking. It is the states sovereign responsibility to zone land for the economic development of the country, says Mr Chatterjee. The state cant abdicate its role.

Contributors

James Lamont South Asia Bureau Chief Joe Leahy Mumbai Correspondent Amy Kazmin New Delhi Correspondent James FontanellaKahn India Editor, FT.com Martin Brice Designer Ursula Milton Commissioning editor Andy Mears Picture editor For advertising contact: Angela Mackay +852 2905 5552 angela.mackay@ft.com or your usual representative

FINANCIAL TIMES WEDNESDAY DECEMBER 16 2009

Indian Infrastructure

Drive to make the traffic f low

ROADS

Funding stages a comeback

The last deal in Indias equity capital markets before the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 was in infrastructure. Reliance Power, controlled by billionaire industrialist Anil Ambani, raised about $3bn in Indias largest initial public offering just before the global markets collapsed. This year, history is repeating itself with the infrastructure sector leading a slew of new listings on the market. The latest to announce an IPO is Jindal Steel & Power, controlled by Indias richest woman. It plans to raise Rs100bn through the sale of its electricity generation unit. The deal will be the countrys secondbiggest initial public offering, signalling a high point in the resurgence of Indias equity issuance market. India had raised $20.5bn in share offerings this year until the end of November, compared with $13.8bn in 2008 and $33.4bn in 2007, according to figures from Dealogic, the data company. Much of this has come from infrastructure companies, such as staterun National Hydroelectric Power Company. Aside from Jindal Steel and Energy, the pipeline for listings includes a $1bn IPO by Sterlite Energy, a unit of Londonlisted Vedanta Resources, and a $583m offering already under way by another Jindal family company, JSW Energy. Property companies with large interests in infrastructure such as Emaar MGF Properties, which is building many of the facilities for Indias Commonwealth Games next year also are holding IPOs. Emaar wants to raise nearly $800m. But analysts say pricing will be critical if the IPO boom is to continue and infrastructure is to retain its sheen in the eyes of the countrys retail investors. A lot of issues that have been coming to market have not been able to attract sustained investor interest because of very high valuations, says Ajay Parmar, head of research at Emkay, a Mumbaibased brokerage. Jindal Steel & Power is one of the more colourful infrastructure companies to have come to market. The group is run by Savitri Jindal, estimated last month by Forbes magazine as the countrys richest woman and the seventh wealthiest individual, with a fortune of $12bn. The nonexecutive chairwoman of the OP Jindal Group, which she took over after her husband died in a helicopter crash in 2005, her net worth has increased by $9bn in the past year on the back of a rise in the share price of Jindal Steel & Power. Her late husband, Om Prakash Jindal, founded the group in 1952 and divested companies to his four sons during his lifetime, which they run independently.

Activity to improve quality and attract investment has increased says James FontanellaKhan

ndias 3.4m km of roads one of the biggest networks in the world are in for a big change, if the governments $20bn overhaul plan is carried out. The Congress-led coalition government which was re-elected in May has said that improving the road network was a top priority and announced a number of reforms to support its ambitious plans to build 12,000km of highways and introduce Europeanstyle toll routes. The decision of Indias prime minister Manmohan Singh to appoint Kamal Nath, a political heavyweight, roads and highways minister, was the first significant sign that the government was serious about its commitment to overhaul Indias potholed roadways. A former commerce minister and high-profile negotiator at the World Trade Organisation, Mr Nath set the agenda from day one. In an interview with the Financial Times shortly after his appointment, he admitted that the roads were in a mess and pledged to build 20km of new ones a day. In July, he told investors in Mumbai, the countrys financial hub, that the government was planning to build 12,000km of highways this year which would cost close to Rs1,0000bn. The countrys roads, of which about 80 per cent are rural, have been in a dismal state for years, marred by potholes and routes that abruptly break off. The lack of investment in construction has been a serious hindrance to development and economic

Welcome relief: Kamal Nath, highways minister, has pledged to build 20km of roads a day

Bloomberg

growth aspirations, according to analysts. In a report: Infrastructure in India a vast land of construction opportunity, PwC, the consultancy, said India is targeting investment in roads of $92bn in the five years to 2012. Currently, the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) is inviting bids for 65 highway projects, the equivalent of 6,800km of road for a total cost of Rs680.8bn. However, according to research by Macquarie, the Australian investment bank, only 15 have been awarded so far. Another 50 are still up for grabs.

Building had been hampered by disagreements between the government and private sector companies over whether roads would yield enough revenues to justify investment. Poor political management, bureaucracy and land disputes have also slowed efforts to improve the crumbling network. Furthermore, the global financial crisis has made financing harder to come by and blocked several projects that were in the pipeline. [The] roads sector has remained moribund in the past 24 months as availability of funding and appetite for the projects dried up, according to the Macquarie

report. Most analysts believe Mr Naths plan to build 20km a day is unrealistic, given the governments record. Infrastructure experts say that

The big deterrent is our own structural and management strength to do it

7km to 10km a day is a more reasonable target. The goal set by Kamal Nath . . . is very ambitious, hard to believe, says Somesh Agrawal, an infra-

structure analyst at Macquarie in Mumbai. However, most analysts, including Mr Agrawal, say that since Mr Nath took over the ministry in June, activity to improve roads and attract private sector partners has stepped up. At a conference in London Building India: Road Infrastructure Summit Mr Nath told investors: We are modifying certain rules to make it much more investment-friendly and investment-worthy. In August, the government launched a roads finance corporation to raise $10bn from international investors and it has staged a number of roadshows to

meet potential private partners. It has also announced plans to facilitate foreign direct investment to make it easier and more profitable to invest in the sector. To render projects more attractive, the ministry has increased the concession periods to 26-36 years from an average of 18-20 years, making it easier for private companies to recover their investment. Finally, land acquisition rules, which have been one of the biggest impediments to construction, according to Ridham Desai, Morgan Stanleys chief India equity strategist, are being changed. This will make it easier for investors to buy land to build roads. We have a new land acquisition bill that is in the floor of the parliament, which will ease land acquisition and therefore accelerate road spending. So what we think is going to happened is that in 2010 you should see a big uptick in highway construction, says Mr Desai. Mr Nath is convinced that the actions taken by the government will help turn round the road network within the next three years. I dont see why we cant do it. We have to resolve a lot of things. We have to structurally strengthen ourselves. We have to have the right models. The least of our problems [now] is financing, because international and domestic finance is there. Our financial system is in good shape. The big deterrent is our own structural and management strength to do it. If you want to build a road, you need a feasibility study, you have got to have proper bid documents. If the model of inviting bids is not right, then you are dead. Investors and analysts are clearly backing him for the time being, although scepticism lingers among the business community. Mr Nath is determined to prove them wrong.

Joe Leahy

Anil Ambani raised $3bn before the crisis

Reuters

Urgency is lacking in spite of chronic deterioration

PROFILE MUMBAI

Joe Leahy says firsttime visitors are often shocked by the dilapidated state of services

Ashok Chavan, the most powerful government official in Mumbai, appears remarkably sanguine when challenged that Indias financial capital is falling chronically behind in terms of the its dilapidated physical infrastructure. Might not another city or even country start to eat Mumbais breakfast unless it can rapidly improve its crumbling roads, railways, airports and housing stock? No, no, I dont believe that, he says dismissively. He is sitting in the courtroom-like greeting hall of his official residence, sipping sugary tea and fielding requests from waves of supplicants who flood the room even at this late hour. New York City is as bad as Indian cities traffic-wise. I have travelled all over the world, so I have seen traffic conditions in England also. Its as good or bad as India. Mr Chavan is probably alone among city residents in having such a rosy view of the infrastructure problems. Many wryly point out that senior officials do not have to worry about traffic bottlenecks because the police clear the roads ahead of their convoys. Mumbai residents retain enough of a sense of humour to joke about the problem, but for Indias economy, the deteriorating condition of the countrys largest metropolis of 18m people is a growing concern. Although it generates about 40 per cent of tax revenue, it appears to enjoy few of the fruits of government expenditure. [Mumbai] remains Indias premier business city it topped Chennai and Bangalore in investment in 2007 and was the top destination for domestic migrants, the World Bank wrote in its World Develop-

The citys trains are so overcrowded scores of people are killed every month falling from the carriages

AP

ment Report 2009. But how quickly it reforms its regulations and builds infrastructure will decide how long it will keep this position. Visitors coming for the first time to the city expecting to see the glitz of one of

I have travelled all over the world so I have seen traffic conditions in England also. Its as good or bad as India

the worlds most rapidly emerging business and movie capitals are often shocked. On the way from the airport to the southern business district they will see seas of slums as their vehicle crawls through hours of rush hour traffic. They might take the new Sea Link bypass bridge, which is meant to be an expressway to the south. But after years of work, the project is only one third complete and is already

becoming congested. They could try to take a train. But Mumbais commuter railway system is so overcrowded scores of people are killed every month falling from the carriages. The government is not even able to provide basic facilities such as potable water, a disgusted bench of High Court judges hearing a pollution case was recently quoted as saying in a local newspaper. The World Bank said the government designed Mumbai in the 1960s and 1970s for 7m people and imposed restrictions on construction to ensure it did not grow beyond that size. The population is now more than double this target, yet the restrictions remain. This has forced newcomers into the slums, which now house more than half the population. The citys state government, headed by Mr Chavan, counters that it is building numerous road, flyover, bridge, rail and housing projects to ease problems. But the government

already has its hands full trying to relocate millions of slum dwellers who mostly live illegally on state land, by the roadsides (often literally on the road) and even on nationally important sites, such as the international airport. Mumbai has few open spaces available for relocation. Moreover, politicians are reluctant to see their constituents moved to other areas and criminal slumlords the gangsters who run many of the land and other rackets in the slums are opposed to the dismantling of their power bases. Even if the slum-dwellers could be moved, many doubt the government would show much urgency on infrastructure. It is more preoccupied with courting the rest of the population of Maharashtra state, who are mostly poor farmers and a far larger electoral group. In addition, the political debate has been hijacked by regionalism, as opposed to practical issues such as infrastructure. The large number of migrants from elsewhere in the country has led to a backlash from Marathi politicians, who represent the native people of the state, whose hero is a medieval warrior king, Chhatrapati Shivaji. Mr Chavans government, a coalition of the secular Nationalist Congress Party and Congress, has defeated the nativists in consecutive elections, but in the process, some of their politics have been co-opted. In fact, he says one giant construction scheme that is making progress is a plan for a Statue of Liberty-sized monument to Shivaji that will be built in the Arabian Sea overlooking south Mumbai. The architects have submitted designs, which government officials are now looking over. A lot of people have a lot of respect for the ancient warrior king, Mr Chavan says, before signalling an end to the audience with the FT. With another wave of political supplicants entering the room, he has more important things to do than talk about infrastructure.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- IMJ - International Multi Disciplinary JournalDocument81 pagesIMJ - International Multi Disciplinary JournalConfidence FoundationNo ratings yet

- CFP Syllabus Module 1 FPSB Investment Planning Specialist GuideDocument41 pagesCFP Syllabus Module 1 FPSB Investment Planning Specialist Guideanand maheshwariNo ratings yet

- Hath Way FinalDocument543 pagesHath Way FinalvishalchatlaniNo ratings yet

- Will Upcoming Real Estate IPOs SucceedDocument14 pagesWill Upcoming Real Estate IPOs Succeedk2samayNo ratings yet

- Stock Market Crash of BangladeshDocument25 pagesStock Market Crash of Bangladeshblue_sky78682% (11)

- SME-CS PS RaoDocument29 pagesSME-CS PS Raonilesh nayeeNo ratings yet

- 300 CubitsDocument2 pages300 CubitsTauseef AhmadNo ratings yet

- SULAVYDocument48 pagesSULAVYSangayamoorthy Subbaraman SNo ratings yet

- Case #12: What Are We Really Worth? (Valuation of Common Stock)Document7 pagesCase #12: What Are We Really Worth? (Valuation of Common Stock)Julliena BakersNo ratings yet

- Finance Report On Project TrainingDocument89 pagesFinance Report On Project TrainingAbhijeet SinghNo ratings yet

- Union Carbide & Netscape Case Analysis: Winning Business & IPO ValuationDocument1 pageUnion Carbide & Netscape Case Analysis: Winning Business & IPO ValuationVasundhara ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Financial MarketsDocument9 pagesFinal Exam Financial MarketsLorielyn Mae SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Adr - GDRDocument81 pagesAdr - GDRPankaj ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Merchant Banking Final NotesDocument45 pagesMerchant Banking Final NotesAkash GuptaNo ratings yet

- Mankind Pharma IPO Note Ashika ResearchDocument5 pagesMankind Pharma IPO Note Ashika ResearchKrishna GoyalNo ratings yet

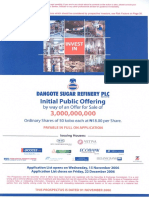

- Dangote Sugar Offer SummaryDocument79 pagesDangote Sugar Offer SummaryBilly LeeNo ratings yet

- Capstone Project 2017Document10 pagesCapstone Project 2017Sohon ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- 1824 Rules Difference List v1.1Document3 pages1824 Rules Difference List v1.1ThomNo ratings yet

- FIN 335 Milestone One Draft of Market OverviewDocument6 pagesFIN 335 Milestone One Draft of Market Overviewproficientwriters476No ratings yet

- Bangladesh Capital Market ReportDocument8 pagesBangladesh Capital Market ReportAldrich Theo MartinNo ratings yet

- Company Prospectus GuideDocument31 pagesCompany Prospectus GuideJaiminBarotNo ratings yet

- Assignment IPODocument10 pagesAssignment IPODebadipta SanyalNo ratings yet

- 2007 New Media Merger Acquisition RoundupDocument40 pages2007 New Media Merger Acquisition RoundupbuttercupsNo ratings yet

- Initial Public Offering (IPO)Document15 pagesInitial Public Offering (IPO)ackyriotsxNo ratings yet

- In Re Facebook - Petition To Appeal Class Cert Ruling PDFDocument200 pagesIn Re Facebook - Petition To Appeal Class Cert Ruling PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- FIN222 Tutorial 1S - TDocument9 pagesFIN222 Tutorial 1S - TYap JeffersonNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument96 pagesCase StudynancykallasNo ratings yet

- Cemex Holdings Philippines Annual Report 2016 PDFDocument47 pagesCemex Holdings Philippines Annual Report 2016 PDFFritz NatividadNo ratings yet

- Smart Investment EnglishDocument72 pagesSmart Investment Englisharpit duaNo ratings yet

- UST Taxation Law - Hernando Case DigestsDocument47 pagesUST Taxation Law - Hernando Case DigestsLuis NovalNo ratings yet