Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Mere Exposure Phenomenon A Lingering Melody

Uploaded by

Augustus CignaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Mere Exposure Phenomenon A Lingering Melody

Uploaded by

Augustus CignaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Mere Exposure Phenomenon: A Lingering Melody by Robert Zajonc

Richard L. Moreland Sascha Topolinski Abstract

Emotion Review Vol. 2, No. 4 (October 2010) 329339 2010 SAGE Publications and The International Society for Research on Emotion ISSN 1754-0739 DOI: 10.1177/1754073910375479 er.sagepub.com

Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, USA

Department of Psychology IISocial Psychology, University of Wrzburg, Germany

The mere exposure phenomenon (repeated exposure to a stimulus is sufficient to improve attitudes toward that stimulus) is one of the most inspiring phenomena associated with Robert Zajoncs long and productive career in social psychology. In the first part of this article, Richard Moreland (who was trained by Zajonc in graduate school) describes his own work on exposure and learning, and on the relationships among familiarity, similarity, and attraction in person perception. In the second part, Sascha Topolinski (a recent graduate who never met Zajonc, but found his ideas inspirational) describes his own work concerning embodiment and fluency in the mere exposure effect. Also, several avenues for future research on the mere exposure phenomenon are identified, further demonstrating its continuing relevance to the field.

Keywords

affect, cognition, mere exposure

This article is a collaboration between two people who have never met. But we do have something in common, namely an interest in understanding the mere exposure phenomenon. That phenomenon is just one of many identified and analyzed by Robert Zajonc during his impressive career as a social psychologist. We have written the article in a somewhat personal way, reflecting our fascination with the mere exposure phenomenon and our admiration for Zajoncs work on it. Age before beauty, the old saying goes, and so our article will begin with comments by Richard Moreland and end with comments by Sascha Topolinski.

1973The Melody Begins

In the summer of 1973, my wife (Nancy) and I moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan. She began to work in Detroit at a large international accounting firm. Nancy also began to take evening classes at the University of Michigan, working toward a graduate degree in accounting. Meanwhile, I sat around in our new apartment, keeping odd hours, eating too much, watching

old films on the television, and worrying about starting graduate school in the fall. I had been admitted to the University of Michigans Department of Psychology and assigned to work with Dr. Robert Zajonc. I knew that he was a famous social psychologist, and I was familiar with at least some of his work, on such topics as social facilitation and the mere exposure phenomenon. But there was much more to learn about Bob, as I later discovered. I decided that my best option was to simply meet Bob and hear what he wanted me to do in the fall. So I made an appointment with him by telephone, and when the fateful day came, I took the bus to the Institute for Social Research (ISR) and eventually found Bobs office. I sat down, introduced myself, and exchanged a few pleasantries. Then I told Bob that I wanted to do good work for him in the fall, and so I thought it would be helpful if he described whatever plans he had made for me. Bob said there were many things I might do, but he hoped I would become involved in some animal research that he was doing, mostly with chickens. I was disappointed, but tried to hide it. I had never done any animal research, and in fact, I was secretly

Corresponding author: Sascha Topolinski, Department of Psychology IISocial Psychology, University of Wrzburg, Roentgenring 10, 97070 Wrzburg, Germany. Email: sascha.topolinski@psychologie.uni-wuerzburg.de.

330

Emotion Review Vol. 2 No. 4

proud to be one of the first people in my family to escape life on the farm. I managed to keep smiling as Bob spoke, but I did not commit myself to anything and left as soon as possible. I told Bob that I would get back in touch with him before the fall semester began. That night, at the apartment, I told Nancy what had happened and asked for advice about what to do next. I am not a very assertive person, and back then I was even meeker than I am now. But Nancy and I decided that I should just tell Bob that I preferred to do research on humans and that I was reluctant to do any animal research. If that made Bob angry with me, even angry enough to reject me as a student, then Nancy and I would just try to live with those consequences. Luckily, our worries were unfounded. Bob was very gracious when I clarified my research preferences. He offered me opportunities to work on several topics, all of which involved human research, and after a bit of discussion we decided that I would work on the mere exposure phenomenon. I joined several other graduate students who were already working with Bob on various topics. These students included Rick Crandall (who later became my officemate), Bill Wilson, and Hazel Markus. They proved to be a wonderful group of colleagues interesting, intelligent, and fun. I could write a whole article about any one of them. Bob had written a famous paper (Zajonc, 1968) on the mere exposure phenomenon just a few years earlier. Although several psychologists had already noted that familiar objects tend to be likeable, Bob was the first person to formalize that observation as a hypothesis, one that he stated in strong terms. (I later learned that this was characteristic of all Bobs workhe liked to present his ideas as simply and boldly as possible, and then search for supportive evidence wherever he could, sometimes in odd places.) Bob argued that the mere repeated exposure of an object to a person (mere exposure in the sense that the object is just accessible to perception) is sufficient to improve someones attitude toward that object. Bob offered correlational and experimental evidence to support this hypothesis. The correlational evidence involved the fact that words used more often (not just in English, but in other languages too) tend to refer to more positive things. But is this because repeated exposure to words causes their referents to be liked better, or because people speak more often about likeable things? To help resolve that issue, Bob carried out several experiments in which novel stimuli of various kinds, such as nonsense syllables, Turkish words, Chinese ideographs, and photographs of male faces, were presented to participants at different frequencies. The participants were not required to respond to such stimuli in any way, but simply had to watch them. After the exposure portion of each experiment ended, participants evaluations of the stimuli were assessed. The results showed that stimuli viewed more often were evaluated more favorably (evaluations were actually a logarithmic function of exposure frequency). Apparently, Zajonc was correctmere exposure to an object was indeed sufficient for the development of a positive attitude toward that object. Why should mere exposure to an object make a person like it more? Several explanations for this phenomenon have been

offered over the years, but at the time when I began my work with Bob, the leading contender involved the notion of response competition. According to that explanation, people are uncertain about how to deal with a novel stimulus. What does it mean? How can (should) it be handled? At first, multiple and often incompatible responses seem possible. This is an unhappy state of affairs. With repeated exposure to the stimulus, however, some of the possible responses are abandoned, because they are too difficult, fail to produce sufficiently positive outcomes, or actually produce negative outcomes. The resulting decline in response competition is pleasurable, and that pleasure becomes associated with the stimulus itself, making it seem more likeable. As an aside, it seems to me that this explanation for the mere exposure phenomenon is not so different from the perceptual fluency explanation that was proposed years later, the explanation favored by Sasha Topolinski and his colleagues. But at the time I was in graduate school, we were blissfully unaware of what perceptual fluency means and how it might produce exposure effects. Relevant work only began to appear in the 1980s (e.g., Jacoby, 1983; Mandler, Nakamura, & Van Zandt, 1987), and by that time, both Bob and I had moved on to pursue other interests. Direct evidence for the response competition explanation first came from Harrison (1968), an earlier student of Bobs who studied the mere exposure phenomenon in his doctoral dissertation. Other researchers later used different methods to study the role of response competition in the mere exposure phenomenon; their results were generally supportive as well (e.g., Matlin, 1970, 1971; Saegert & Jellison, 1970). Attention then turned toward the identification of variables that might moderate the mere exposure phenomenon, making it stronger or weaker. Although this research was certainly valuable, it sometimes produced results that were hard to explain in terms of response competition. For example, some studies (Smith & Dorfman, 1975) revealed an inverted-U relationship between mere exposure and likingrepeated exposure led first to an increase, but then later to a decrease, in evaluations of stimuli. And some studies showed that though stimuli that were initially liked became even more likeable with repeated exposure, stimuli that were initially disliked became even less likeable (e.g., Grush, 1976). Results like these opened the door for critics to offer new explanations of their own for the results of mere exposure research. Stang (1974, 1975, 1976), for example, argued that repeated exposure initially increases liking for a stimulus because it allows someone to learn more about that stimulus, but once such learning has occurred, further exposure to the stimulus is boring and thus decreases the persons liking for the stimulus. Stang also raised the issue of demand characteristics as a factor in the mere exposure phenomenon. He provided some evidence that participants in the typical experiment (a) are aware that some stimuli are being shown to them more often than others, (b) believe that familiar things are generally liked better than unfamiliar things, and (c) evaluate the stimuli they have seen accordingly.

Moreland & Topolinski

Mere Exposure

331

Stangs arguments shaped my own early work on the mere exposure phenomenon. I was called to Bobs office in early 1973 to discuss research plans. There I experienced something that would happen again many times during the years that followedBob first identified a theoretical issue that he believed we should study, and then asked me to design and carry out a study that could resolve that issue. I was given almost complete independence in both regards, which shocked me then (and still does now), because Bob knew so much more than I did about research. I should say that Bob was always available to answer questions about any project on which we were working, and he was more than willing to offer advice about our projects when I asked for help. On several occasions, he helped me to identify different ways of analyzing our data that eventually produced stronger results in support of our hypotheses. But Bob was also happy to let me just work on my own, checking in occasionally to report on any progress. Im not sure why Bob treated me this way. My favorite explanation is that he trusted me to do a good job and thus believed that closer supervision was not really necessary. But in my darker moments, other explanations have sometimes occurred to me. It may be that Bob didnt believe the projects we worked on were very important, and so it mattered little to him whether they succeeded or not. Or maybe Bob was more concerned with other projects on which he was working, so he was willing to take some risks with our projects, if that freed time and energy for him. In any event, I like to think that I nearly always rose to the occasion and produced projects that made both Bob and me proud. The first issue that Bob identified for me was whether demand characteristics are an important factor in the mere exposure phenomenon, as Stang had argued. Keeping that issue in mind, I designed two related studies (Moreland & Zajonc, 1976). The first was a role-playing study in which participants were given descriptive materials that revealed events (in their usual sequence of occurrence) that someone might experience during a typical study of exposure effects. After each new set of events was described, people were asked what they thought this hypothetical study was all about. I was especially interested in whether they believed that the relationship between stimulus exposure and liking was being tested, and if so, then what they thought that relationship might be. The second study was an experiment in which the frequency with which stimuli were shown to participants was manipulated between rather than within subjects (the latter kind of manipulation is used in nearly all research on the mere exposure phenomenon). In such an experiment, it would be difficult or impossible for participants to guess that the effects of repeated stimulus exposure were being studied, because all of the stimuli that any one person saw would appear the same number of times. I wondered whether the mere exposure phenomenon could still occur under these conditions. (A problem that I have often experienced over the years arose here for the first timecomplex statistical data analyses were needed for the data from this experiment, analyses with which I was not yet familiar.) The results from both studies showed that Stang had exaggerated the role of demand characteristics in the mere exposure

phenomenon. In the role-playing study, few people realized that the effects of stimulus exposure on liking were being studied, and even the people who did realize that did not always believe that stimuli shown more often should be more likeable.1 And in the experiment, the usual mere exposure phenomenon was found, even though stimulus exposure frequencies were manipulated between rather than within subjects. The next issue Bob thought was important was whether learning about a stimulus is really an important factor in the mere exposure phenomenon, as Stang (and others) had argued. But learning can mean many things. Bob reasoned that the most basic form of learning is the simple recognition of a stimulus realizing that it is familiar. If so, then could the mere exposure phenomenon occur if participants could not recognize the relevant stimuli? Bill Wilson investigated this issue in a very direct way, producing impressive findings that gained widespread attention (Wilson, 1979; see also Kunst-Wilson & Zajonc, 1980). Bill asked participants to perform a dichotic listening task. While they listened attentively to material played in one channel of their earphones, participants also heard experimental stimuli (at different exposure frequencies) in the unattended channel. The participants were later unable to distinguish the experimental stimuli from other, similar stimuli that they had never heard before. Stimulus recognition, in other words, was minimal. And yet the mere exposure phenomenon still occurredstimuli that were presented more often were liked better. My own approach to this same issue was more indirect (Moreland & Zajonc, 1977). Two studies were designed. The first involved randomly formed yoked pairs of participants. Two of these pairs participated in each session of a standard mere exposure experiment. The members of each pair were treated exactly the same during the experiment, except at the end, when stimulus evaluations were obtained. At that time, one individual made ratings of liking for the stimuli, while the other made ratings of familiarity. Neither person was aware that the other was making ratings of a different sort. In analyzing the data, I treated the liking and familiarity ratings from each pair as though they had come from a single individual. Complex statistical analyses (again unfamiliar to me at that time) were then carried out. The results showed that when exposure frequencies and familiarity ratings for the stimuli were used to predict how well those stimuli were liked, each predictor had its own significant positive effect. It thus appeared that repeated exposure to a stimulus could make it more likeable, regardless of how familiar it seemed. In the second study, participants were first shown Japanese ideographs at different exposure frequencies. Afterwards, they rated the familiarity of the stimuli and tried to guess their meaning (by reviewing a list of trait adjectives and selecting the words that seemed most likely to reflect each ideograph). The positivity of the words that were selected provided an unobtrusive measure of how well the ideographs were liked. Exposure frequencies and familiarity ratings were then used to predict this measure of liking, and both predictors again had significant positive effects, just as in the first study. Once again, repeated exposure to a stimulus made it more likeable, regardless of how familiar it seemed.

332

Emotion Review Vol. 2 No. 4

Taken together, these two studies suggested that the mere exposure phenomenon could occur without learning (in the form of stimulus recognition). For better or worse, however, the paper describing those studies attracted critical attention from two people at the University of Illinois, Michael Birnbaum and Barbara Mellers. They submitted a paper of their own (Birnbaum & Mellers, 1979a) to the same journal in which ours was published, a paper in which they used the pattern of correlations (from each of our studies) among frequency of exposure, familiarity, and liking to show that a single-factor model of the results was possible. According to that model, repeated exposure created a factor (which they named subjective recognition), which then served as the basis for both familiarity and liking ratings. The fact that this model fit the data fairly well led Birnbaum and Mellers to conclude that the effects of repeated stimulus exposure on liking were mediated by learning about the stimuli. You can imagine my dismay, as a young graduate student, at this public criticism of my research with Bob. To my surprise, however, Bob was not at all upset. In an effort to calm me, Bob noted that controversy (aside from its scientific benefits) can actually aid a persons career (see Christensen-Szalanski & Beach, 1983). Bob suggested that we fight back, and so he sent me to Frank Andrews, an ISR colleague who was (among other things) an expert on causal modeling via structural equations analyses. Frank was generous with his time, in part because our problem intrigued himhe had not yet seen any applications of structural equations analyses to experimental (versus correlational) data. Frank introduced me to LISREL, a piece of software for performing such analyses, and I spent many hours with LISREL, struggling to analyze my data in new ways. I ended up testing two causal models. We reported the results of those analyses in Moreland and Zajonc (1979). In our preferred model of the data, repeated exposure to a stimulus had a positive effect on two distinct (but correlated) factors, one associated with liking and one associated with familiarity. Both effects were significant, and the overall model fit the data well. This suggested, as we had concluded in our original paper, that learning was not necessary for exposure effects to occur. In the other model, which represented the viewpoint of Birnbaum and Mellers, repeated exposure to a stimulus had a positive impact on a single factor, one that could represent learning (although it could represent other things too). Familiarity and liking were both associated with that factor. Although this model fit the data reasonably well, it did not fit them as well as our model did, and so we rejected it. Birnbaum and Mellers (1979b) later mounted a counterattack, which appeared in the same issue of the journal. In that paper, they presented new structural equations analyses that differed from ours in several minor ways, but seemed to favor their one-factor model of the data over our two-factor model. Whether they finally won or lost the battle as a result is hard to sayI invite energetic readers with time on their hands to read all of these papers for themselves and make up their own minds. I suspect that everyone was relieved when the matter was finally allowed to rest, with no further publication by either side. Speaking for myself, I was certainly happy to move on.

Bob and I received some vindication years later from a meta-analysis by Bornstein (1989) of research on the mere exposure phenomenon. Bornstein found that the mean effect size for the phenomenon was substantial, and he identified several interesting moderators of the phenomenon. One such moderator was whether participants were aware of repeated stimulus exposure or not. Bornstein found that not only could the mere exposure phenomenon occur among participants who were unaware of such exposure, but it was actually stronger under those conditions! He went on to develop an attributional discounting explanation for this surprising finding. Bornstein argued that when people are aware that repeated stimulus exposure has occurred, they feel greater liking for stimuli that were shown more often, but attribute some of that liking to the repeated exposure, and thus like the stimuli themselves somewhat less. To put this another way, people allow an extrinsic factor (repeated exposure) to reduce the intrinsic value of the stimulus. But when people are not aware that repeated stimulus exposure has occurred, attributional discounting of this sort does not happen, and so the (enhanced) value of the stimulus remains intact. Bornstein and others later carried out experiments in which the awareness of stimulus exposure was manipulated directly (e.g., Bornstein & DAgostino, 1992). The results of this research were consistent with the findings from the meta-analysis (where studies in which participants were aware of stimulus exposure were compared to studies in which participants lacked such awareness). Bill Wilsons research, along with my own research and that of several others who worked with Bob, eventually led Bob to a broader conclusion, namely that affect does not always depend on cognition. Sometimes cognition can depend on affect, and affect and cognition can even operate independently at times. Bob offered and defended this conclusion in a series of famous papers, most notably Zajonc (1980), but see also Zajonc (1984, 2001), and Zajonc and Markus (1984). Although I had little to do with these papers, they had an impact on my efforts to find an academic job after graduating from Michigan. Many of my invitations for job interviews were based on the mistaken impression that I could contribute to the affect versus cognition debate. My only other research with Bob on the mere exposure phenomenon arose from an interest in research on exposure effects in person perception. I believed that there might be a link between this work and Heiders (1958) balance theory, especially when it came to the relationships among familiarity, similarity, and liking. (Bob had already done some work of his own on balance theory [e.g., Zajonc & Burnstein, 1965], and on the possible role of mere exposure in the development of interpersonal attraction [Saegert, Swap, & Zajonc, 1973].) According to Heider, beliefs about people include unit relations (people belong together or apart) and sentiment relations (people are liked or disliked), and we prefer such beliefs to be consistent or balanced. Balance is achieved when people who have a positive unit relationship (e.g., a married couple) have a positive sentiment relationship as well (e.g., love), or when people who have a negative unit relationship (e.g., a divorced couple) also have a negative sentiment relationship (e.g., hate). It seemed to

Moreland & Topolinski

Mere Exposure

333

me that both familiarity and similarity implied unit relations, whereas liking implied a sentiment relation. So, balance theory suggested to me that as someone becomes more familiar, that person should not only seem more likeable, but also more similar to the self. And as someone becomes more similar to oneself, that person should not only seem more likeable, but also more familiar. I found evidence for several of these links in past research on person perception in social psychology. But to test my ideas more directly, I designed two new experiments (Moreland & Zajonc, 1982). In one of these experiments, participants were first shown photographs of faces at different exposure frequencies. Afterward, they rated the people in those photographs for both likeability and similarity to themselves. As expected, people whose photographs appeared more often were rated as both more likeable and more similar, and there was some evidence that the effects of familiarity on perceived similarity were mediated by changes in likeability. The same photographs were shown to the participants in the second experiment, but every photograph appeared at the same exposure frequency. Participants were given bogus information about how similar the people in those photographs were to themselves. Afterward, the participants rated those persons for both likeability and perceived familiarity. As expected, people who were viewed as more similar to the self were rated as both more likeable and more familiar. And there was strong evidence that the effects of similarity on perceived familiarity were mediated by changes in likeability. The results of these experiments suggested that familiarity, similarity, and liking have strong connections with one another, so strong that they might actually be parts of a single, complex construct (dominated by liking), not three different constructs. Bob said this construct reminded him of what is commonly called affinity. Years later, when I was a faculty member myself, I studied affinity again, this time with Scott Beach, a graduate student at my university. We designed a field experiment (Moreland & Beach, 1992) in which several female confederates (all comparable in appearance) visited a large undergraduate course, pretending to be students in it. On selected days, one of these confederates entered the back of the classroom (arriving a bit late, so she could be seen by everyone who was already there), walked down to the front row, and took a seat. The confederate then sat quietly (apparently taking notes) until the lecture ended, when she left the room with everyone else, but without talking to anyone. Our goal in all this was to produce conditions of mere exposure. None of the actual students in the course realized that an experiment was in progress. Each confederate visited the course a different number of times. At the end of the semester, students viewed slides of the confederates and rated how familiar, likeable, and similar (to themselves) each woman seemed. Structural equations analyses were then carried out to see whether frequency of exposure (number of classroom visits) had any effects on those three variables, and how the variables related to one another. The results revealed that repeated exposure had weak effects on familiarity, but strong effects on likeability and similarity. All of

these effects were positive. Several causal models of the data were tested, including ones in which familiarity, likeability, and similarity were treated as a single latent factor or as separate factors. In the best-fitting model, where separate factors were assumed, repeated exposure affected likeability, which then affected both familiarity and similarity (which did not affect one another). As my time at Michigan went on, I worked less often with Bob, due to my growing interest in small groups. I spent more time talking to and working with Gene Burnstein instead, and I owe Gene a great deal for his thoughtful supervision and collaboration. I did play a small role in Bobs later research on the confluence model of intellection development, working primarily with Mike Berbaum, who was another one of Bobs students (Berbaum & Moreland, 1980, 1985; see also Berbaum, Moreland, & Zajonc, 1986; Moreland, 1985; Zajonc, Berbaum, Hamill, Moreland, & Akeju, 1980; Zajonc, Markus, Berbaum, Bargh, & Moreland, 1991). After I graduated from Michigan, my work with Bob was largely done, though we certainly remained in contact and he was always a good friend and supporter. But although I no longer worked with Bob, he was always with me in spirit, and will probably remain with me in that way so as long as I am alive and working as a social psychologist. He taught me most of what I know about analyzing and studying social behavior. I was very lucky to have Bob as a mentor.

2007The Melody Lingers On

Only a few things from my undergraduate studies in social psychology (during the early 2000s) remained vivid in my memory later on. Among them was the mere exposure phenomenon, something discovered by Robert Zajonc, a giant in the field, several decades earlier. Yet the mere exposure phenomenon did not seem like something I should do research on myself. Instead, it was like the periodic system of elements in chemistry: an established fact that might serve as a conceptual tool, but could not be the target of my own research. Even my early work on fluency (see below) did not initially involve the mere exposure phenomenon. I was certainly aware of the phenomenon, but primarily it interested me because of its general relationship with fluency and affect, as described in an ingenious review paper by Rolf Reber, Norbert Schwarz, and Piotr Winkielman (2004), which had a deep impact on me. Honestly, it was only by chance that I ever studied the mere exposure phenomenon. In the summer of 2007, Fritz Strack and I began to investigate the reading fluency of word triples for a project on intuition (e.g., Topolinski & Strack, 2009d). We asked participants to chew gum while reading word triples, in order to interrupt their feelings of reading fluency. After piloting the experimental session, which was meant to be an hour in length, I realized that there were still five minutes left at the end of the session. As is my habit, I looked for a small task to fill those few minutes. What else could be hampered by chewing gum? Following a vague intuition, I connected the fluency explanation for exposure effects (see below) to reading fluency. Would

334

Emotion Review Vol. 2 No. 4

chewing gum interfere with the mere exposure phenomenon? In that first session, it turned out that chewing gum destroyed the phenomenon, a finding that I later replicated numerous times. I was thrilled by this finding, especially because it connected embodiment research with the mere exposure effect. Soon I realized that the literature was actually full of recent studies on the mere exposure phenomenon. Far from being an old and halfforgotten phenomenon, it was associated with many current theoretical issues, all hotly debated. As Richard Moreland has already described, researchers were interested right from the start in why the mere exposure phenomenon occurs. Some of the main contenders, during the first generation of research on the phenomenon, were response competition (Harrison, 1968), arousal (Berlyne, 1966, 1971, 1974; Crandall, 1970), and habituation/boredom (Berlyne, 1970; Stang, 1974). However, none of these early explanations could account for all of the findings in the literature (see Bornstein, 1989). Thus, the best explanation was far from clear, even in the 1980s, more than 10 years after the phenomenon was first described by Zajonc.

The fluency notion also helped to connect the preference effects found in mere exposure research with other effects from research on (social) cognition. For instance, repeated exposure to novel propositions (e.g., Osorno is the capital of Chile) causes them to seem more correct, the famous truth effect (Bacon, 1979; Begg, Anas, & Farinacci, 1992; Hasher, Goldstein, & Toppino, 1977; Reber & Schwarz, 1999; Topolinski & Reber, 2010; Unkelbach, 2007). And repeated presentation of the names of ostensible actors causes them to be perceived as more famous (Jacoby & Kelley, 1987; Jacoby, Kelley, Brown & Jasechko, 1989; Jacoby & Whitehouse, 1989). The common denominator in all of these effects was fluency. In sum, this second generation of research on repeated stimulus exposure produced a powerful explanatory tool, namely processing fluency. However, a deeper riddle remained to be solved what was actually the driving force behind fluency gains?

Substrates of Fluency

The fluency explanation for exposure effects seems plausible and straightforward. Repetition leads to increased fluency, which drives preference. However, another question remains, namely, the fluency of what? In processing a stimulus, multiple perceptual, cognitive, and affective processes often run in parallel (see Borowsky & Besner, 2006, for example). When words are presented to participants, for instance, visual encoding, lexical identification, and semantic retrieval can all occur (cf., Borowsky & Besner, 2006), as well as automatic pronunciation (cf. Stroop, 1935). Which of these processes undergoes fluency gains during repeated exposure? A third generation of mere exposure research has recently begun to address this question (Topolinski, in press; Topolinski & Strack, 2009a, 2010). While investigating the procedural substrates of fluency gains, Fritz Strack and I have adopted the notion of embodiment (Barsalou, 1999, 2008; Niedenthal, 2007; Niedenthal, Barsalou, Winkielman, Krauth-Gruber, & Ric, 2005; Niedenthal, Winkielman, Mondillon, & Vermeulen, 2009; Semin & Smith, 2008; Schubert & Semin, 2010; Wilson, 2002). Embodiment means that people represent the stimuli they encounter by covertly simulating the sensorimotor responses associated with those stimuli (e.g., Barsalou, 2008; Niedenthal et al., 2005, 2009; Semin & Smith, 2008). For example, whenever I see my cup on the desk, I covertly simulate grasping it (Tucker & Ellis, 1998). Moreover, the meaning of the cup to me is the sum of all the actions I do with it, as well as their sensory and affective consequences (Glenberg, 1997). Thus, the meaning of the world is not sealed in dry, amodal concepts, but rather is deeply grounded in modal representations. How things feel, look, and smell, and especially how we act on them, are all very important (Barsalou, 2008; Glenberg & Roberston, 2000). Evidence for this notion has emerged in recent years across various disciplines and domains. Let me consider just one brief example. In their ingenious work, Van den Bergh, Vrana, and Eelen (1990, see also Beilock & Holt, 2007; Yang, Gallo, & Beilock, 2009) presented letter dyads to participants. Some of these dyads consisted of letters that are typed with the same

Processing Fluency and Mere Exposure

Toward the end of the 1980s, a new and powerful explanation for the mere exposure phenomenon arose from both the cognitive and social psychological literature on recognition and familiarity (Jacoby & Dallas, 1981; Jacoby & Kelley, 1987; Jacoby, Woloshyn, & Kelley, 1989; Mandler, 1980; Whittlesea, 1993). This explanation involved processing fluency, which is the speed and efficiency of processing a stimulus (Reber, Schwarz, & Winkielman, 2004; Reber, Wurtz, & Zimmermann, 2004). This became the standard explanation for the mere exposure phenomenon by the end of the 1990s and inspired a second generation of mere exposure research (e.g., Bornstein & DAgostino, 1992; Phaf & Rotteveel, 2005; Reber, Winkielman, & Schwarz, 1998; for earlier analyses of how perceptual fluency might influence exposure effects, see Seamon, Brody, & Kauff, 1983; Seamon, Marsh, & Brody, 1984). The fluency explanation is based on two simple assumptions, both supported by abundant evidence. First, repeated processing of a stimulus results in greater processing fluency (Jacoby & Dallas, 1981; Jacoby & Whitehouse, 1989). For instance, words are read faster after repetition than before (Jacoby & Dallas, 1981; Scarborough, Cortese, & Scarborough, 1977). Second, greater fluency automatically generates more positive affect (e.g., Reber, Schwarz, et al., 2004), which can be demonstrated through both explicit self-reports of liking and mood (Monahan, Murphy, & Zajonc, 2000; Reber et al., 1998; Topolinski & Strack, 2009b, 2009c, 2009d), and through more indirect measures of subtle affective responses that occur outside of awareness (e.g., Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001; Topolinski, Likowski, Weyers, & Strack, 2009; Winkielman & Cacioppo, 2001). Positive affect arising from fluency-gains in processing is assumed to be the reason why stimuli that are exposed more often tend to be preferred (e.g., Phaf & Rotteveel, 2005; Reber, Schwarz, et al., 2004).

Moreland & Topolinski

Mere Exposure

335

finger (using the traditional 10-finger typing method). For instance, F and G are both typed by the left index finger, which implies motor interference. Other dyads consisted of letters that are typed with different fingers, such as F and J. F is typed by the left index finger and J is typed by the right index finger, which implies no motor interference. The task for participants, who were all skilled typists, was simply to indicate their liking for the letter dyads. No actual typing (or other manual response) was required. The researchers found that the typists preferred letter dyads with no motor interference over dyads with such interference. This astonishing result was explained in terms of covert motor simulation. Merely seeing the letter dyads triggered (among these skilled typists) the overlearned response of actually typing the letters. This covert simulation ran more fluently for non-interfering letter dyads than for interfering letter dyads, resulting in more positive affect and preference for the former dyads. Beilock and Holt (2007) recently demonstrated that this effect indeed depends on covert motor simulations. In a similar experimental paradigm, they introduced a secondary manual motor task for some of the participants, one that was designed to block the covert typing simulations. The preference for non-interfering over interfering letter dyads disappeared for participants who executed the secondary manual task. Related phenomena are the findings that individuals prefer letters that are entailed in their own name over other letters (Nuttin, 1985); or that individuals prefer target persons who have the same birthday as they do over other target persons (Finch & Cialdini, 1989). Both these effects may also draw on motor fluency of simulating typing the letters and dates, since the letters of the own name and the own birthday had been typed and written more frequently by an individual than other letters and dates, although this hypothesis was never tested. This research illustrates the more general notion that we covertly simulate the sensorimotor responses that were associated with a particular stimulus in the past, and that the fluency of these embodied simulations shapes our experiences and preferences (Beilock & Holt, 2007; Yang et al., 2009). Applying this notion to the mere exposure phenomenon leads to a straightforward hypothesis concerning the procedural substrates of fluency. Encountering a stimulus, we simulate the specific sensorimotor responses associated with that stimulus. If we encounter the stimulus again, then we repeat that covert simulation, which runs more fluently because it has been trained. This fluency gain triggers positive affect, which makes the stimulus preferable to others that we have encountered less often. The crucial question is which response is dominant for a given stimulus. For words, the dominant, overlearned response is generally pronunciation, as in the wellknown Stroop-effect (Stroop, 1935; for a review, see MacLeod, 1991). We covertly pronounce each word that we encounter. When we encounter a word repeatedly, this covert pronunciation is also repeated and thus runs more fluently (e.g., Scarborough et al., 1977). The litmus test for this embodied account of the mere exposure phenomenon would be to simply block covert stimulus motor

simulations. If people encounter stimuli repeatedly, but the sensorimotor simulations associated with those stimuli are blocked by some means, then exposure effects should weaken. My colleagues and I have tested this prediction in several experiments involving verbal, vocal, and visual stimuli (Topolinski, in press; Topolinski & Strack, 2009a, 2010).

Blocking Sensorimotor Simulations During Mere Exposure

Fritz Strack and I first chose words as stimuli because (a) their associated dominant response (pronunciation) is well-established, and (b) the motor system responsible for that response (the mouth) can easily be identified (e.g., Inoue, Ono, Honda, & Kurabayashid, 2007), and blocked (e.g., Campbell, Rosen, Solis-Macias, & White, 1991; Miyake, Emerson, Padilla, & Ahn, 2004). In Topolinski and Strack (2009a, Experiment 1) we presented participants with nonsense words (e.g., PANTOKRATOR), and also with Chinese characters, which served as control stimuli. Participants were later asked how much they liked each stimulus. Some of the stimuli were repeatedly presented (old), and others were presented just once (new). This was a conceptual replication of classic mere exposure experiments by Stang (1974) and others. Crucially, we also implemented two secondary motor tasks. One task was meant to block covert pronunciation of the words. For that task, we asked participants to chew gum while evaluating the stimuli (oral group). Another task served as a control condition, one in which the pronunciation was allowed to occur naturally. For that task, we asked participants to continuously squeeze a soft foam ball with their nondominant hand (manual group). Although both the oral and the manual participants performed a concurrent motor task, we predicted that the oral task would interfere with covert pronunciation of the words, but not the characters, whereas the manual task would not interfere with covert simulations of the words or the characters. This is exactly what occurred. In the manual group, we found reliable exposure effects for both the words and the charactersold stimuli were liked better than new stimuli. In the oral group, however, we found exposure effects only for the characters, not for the words. It is important to note that blocking pronunciation of the words did not just weaken the mere exposure phenomenon, but completely destroyed itthe mean liking ratings were virtually the same for old and new stimuli. In a further demonstration, we used two different types of stimuli, namely verbal (words) and vocal (tunes), and manipulated their respective motor systems, namely the mouth and the voicebox (Topolinski & Strack, 2009a, Experiment 3). Words are spoken, tunes are sung. We predicted that blocking oral motor simulations would interfere with exposure effects for words, whereas blocking vocal motor simulations would interfere with exposure effects for tunes. To test this hypothesis, we presented words and tunes (some of these were again repeated, whereas others were not) to participants and asked one group to move their tongues in a concurrent oral task (oral group), and another group to continuously hum the sound

336

Emotion Review Vol. 2 No. 4

(umm hmm) that people make when they agree with a speaker (Gardner, 2001) in a concurrent vocal task (vocal group). Note that both tasks are quite specificmoving the tongue engages the oral motor system and leaves the voice box unaffected, whereas humming engages the voice box and leaves the mouth unaffected. This paradigm created a double dissociation between stimulus type and motor interference. In the oral group, we found exposure effects for words, but not for tunes. In contrast, we found exposure effects for tunes, but not for words, in the vocal motor group. These results strongly suggest that the fluency of covert stimulus motor simulations is what drives the mere exposure phenomenon. As I mentioned earlier, repetition-induced fluency influences not only preferences, but also other judgments, such as ratings of truth (Begg et al., 1992; Unkelbach, 2007), and fame (Bornstein & DAgostino, 1992; Jacoby, Kelley, et al., 1989; Jacoby, Woloshyn, et al., 1989). To investigate whether these fluency effects also involve sensorimotor simulations, we replicated the classical false-fame paradigm with an oral task (Topolinski & Strack, 2010). In a first demonstration, we presented the names of Bollywood actors (e.g., AISHWARYA RAI) to participants and asked them to judge how famous these actors were. Some of the names were repeated (old), whereas others appeared just once (new). We also asked some of the participants to eat popcorn (oral), and others to knead a soft foam ball (manual), while rating the names. We found the classical false-fame effect for the manual interference groupold names were judged as more famous than new names. However, we did not find that effect for the oral motor group. In a further demonstration, we investigated whether the most common effect of stimulus repetition, namely increased familiarity, also depends on sensorimotor simulations (Bornstein & DAgostino, 1992; Garcia-Marques, Mackie, Claypool, & Garcia-Marques, 2004; Whittlesea, 1993). For this purpose, we presented participants with the names of Asian stocks (e.g., UNITIKA) and the brand-names of drugs (e.g., DURAGESIC). Again, some of the names were repeated and others were not. This time, we asked participants to rate how familiar the names seemed to them. Furthermore, we asked some of the participants to eat a cereal bar (oral interference), and other participants to knead a foam ball (manual interference), while rating the names. Once again, manual interference left exposure-induced familiarity unaffected, while oral interference destroyed that effectold names were not rated as more familiar than new ones in the oral group. These findings show that the effects of stimulus repetition on judgments of fame and familiarity also depend to some extent on covert sensorimotor simulations. In conclusion, many mere exposure phenomena seem to draw heavily on embodied simulations. In general terms, this embodied view on the mere exposure effect reveals that it is not the stimulus itself that drives these effects, but stimulustriggered bodily reactions: the dynamics of motor efference can create preferences (see also Beilock & Holt, 2007). This in turn connects to yet another fascinating idea that was promoted by Robert Zajonc independently of his work on mere exposure,

namely the vascular theory of facial expression (Zajonc, 1985). This theory, aimed at facial motor efference in emotions, holds that emotional facial muscle reactions are not only epiphenomenal expressions of emotion, but may appear before the emotional experience and may even causally shape it by regulating cerebral blood flow (Zajonc, 1985; see also Adelman & Zajonc, 1989; Zajonc, Murphy, & Inglehart, 1989). This notion of motor efference as a causal determinant of affective experience converges with the idea underlying an embodied notion of the mere exposure effect, in which motor efference also shapes affective responses. This conceptual homology is a fascinating example of how Robert Zajoncs work anticipated current theorizing.

Future Directions

An embodied notion of exposure effects opens the door to many new research questions. For instance, if sensorimotor fluency determines the feeling of familiarity, then does it also influence other experiences that indicate a previous encounter, such as recognition (cf., Yang et al., 2009)? However, other mere exposure effects are less likely to be based on covert sensorimotor simulations. Consider, for instance, the classical finding that pre-exposed Chinese ideographs, being purely visual stimuli, are more liked than novel ones (Zajonc, 1968), even when they are exposed outside of individuals awareness (Kunst-Wilson & Zajonc, 1980). If the fluency hypothesis still holds for this effect, the sources of fluency gain due to repeated exposure are still to be explored. Although there are most recent hints that motor fluency is a causal determinant in this phenomenon (Topolinski, in press), other sources such as visual processes may also play a role. If this is true, can interference with visual processing, such as mental imagery, block mere exposure effects for visual stimuli? This example also illustrates that future research is still needed to elucidate the causal architecture of these classical findings, which again proves how stimulating Robert Zajoncs work still is after decades. Aside from these new research questions, older questions are still being asked. For example, does the mere exposure phenomenon require awareness that some stimuli have been presented more often than others? Older work by Moreland and others suggests that the answer to this question is no, but recent work by Newell and his colleagues (see Newell & Bright, 2001, 2003; Newell & Shanks, 2007) suggests otherwise. Newell and Shanks, for instance, found that stimulus recognition plays a more important role in producing exposure effects than the older work by other researchers, reviewed earlier, suggested. Future research will presumably continue to address this issue.

Conclusion

Recent developments in research on the mere exposure phenomenon show that it is not a dusty antique that belongs in the corner of some museum, but rather is something vital that still commands broad interest from the scientific community. Most of my own current research involves that phenomenon, in one way or another. Unfortunately, I never met Robert Zajonc; he passed away in the same week that the galley proofs for my first paper on the phenomenon arrived in the mail. But standing on

Moreland & Topolinski

Mere Exposure

337

the shoulders of this giant, I am proud to carry forward the research enterprise that he began.

Note

1 The role-playing study was not included in Moreland and Zajonc (1976), because the journal editor did not like it enough. However, a brief description of the study later appeared in a book on attitudes by Rajecki (1982).

References

Adelmann, P. K., & Zajonc, R. B. (1989). Facial efference and the experience of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 40, 249280. Bacon, F. T. (1979). Credibility of repeated statements: Memory for trivia. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 5, 241252. Barsalou, L. W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 577660. Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617645. Begg, I. M., Anas, A., & Farinacci, S. (1992). Dissociation of processes in belief: Source recollection, statement familiarity, and the illusion of truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 121, 446458. Beilock, S. L., & Holt, L. E. (2007). Embodied preference judgments: Can likeability be driven by the motor system? Psychological Science, 18, 5157. Berbaum, M. L., & Moreland, R. L. (1980). Intellectual development within the family: A new application of the confluence model. Developmental Psychology, 16, 506515. Berbaum, M. L., & Moreland, R. L. (1985). Intellectual development within transracial adoptive families: Retesting the confluence model. Child Development, 56, 207216. Berbaum, M. L., Moreland, R. L., & Zajonc, R. B. (1986). Contentions over the confluence model: A reply to Price, Walsh, and Vilburg. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 270274. Berlyne, D. E. (1966). Curiosity and exploration. Science, 153, 2333. Berlyne, D. E. (1970). Novelty, complexity and hedonic value. Perception and Psychophysics, 8, 279286. Berlyne, D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and psychobiology. New York: AppletonCentury-Crofts. Berlyne, D. E. (1974). Novelty, complexity and interestingness. In D. E. Berlyne (Ed.), Studies in the new experimental aesthetics (pp. 175181). Washington, DC: Hemisphere. Birnbaum, M. H., & Mellers, B. A. (1979a). Stimulus recognition may not mediate exposure effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 391394. Birnbaum, M. H., & Mellers, B. A. (1979b). One-mediator model of exposure effects is still viable. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 10901096. Bornstein, R. F. (1989). Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research, 19681987. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 265289. Bornstein, R. F., & DAgostino, P. R. (1992). Stimulus recognition and the mere exposure effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 545552. Borowsky, R., & Besner, D. (2006). Parallel distributed processing and lexical-semantic effects in visual word recognition: Are a few stages necessary? Psychological Review, 113, 181195. Campbell, R., Rosen, S., Solis-Macias, V., & White, T. (1991). Stress in silent reading: Effects of concurrent articulation on the detection of syllabic stress patterns in written words in English speakers. Language and Cognitive Processes, 6, 2947. Christensen-Szalanski, J. J. J., & Beach, L. R. (1983). Publishing opinions: A note on the usefulness of commentaries. American Psychologist, 48, 14001401.

Crandall, J. E. (1970). Preference and expectancy arousal. Journal of General Psychology, 83, 267268. Finch, J. F., & Cialdini, R. B. (1989). Another indirect tactic of (self-) image management: Boosting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 222232. Garcia-Marques, T., Mackie, D. M., Claypool, H. M., & Garcia-Marques, L. (2004). Positivity can cue familiarity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 585593. Gardner, R. (2001). When listeners talk. Response tokens and listener stance. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Glenberg, A. M. (1997). What memory is for. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 20, 155. Glenberg, A. M., & Robertson, D. A. (2000). Symbol grounding and meaning: A comparison of high-dimensional and embodied theories of meaning. Journal of Memory & Language, 43, 379401. Grush, J. E. (1976). Attitude formation and mere exposure phenomena: A nonartifactual explanation of empirical findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33, 281290. Harmon-Jones, E., & Allen, J. B. (2001). The role of affect in the mere exposure effect: Evidence from psychophysiological and individual differences approaches. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 889898. Harrison, A. A. (1968). Response competition, frequency, exploratory behavior, and linking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 363368. Hasher, L., Goldstein, D., & Toppino, T. (1977). Frequency and the conference of referential validity. Journal of Verbal Learning and VerbaI Behavior, 16, 107112. Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Inoue, M. S., Ono, T., Honda, E., & Kurabayashid, T. (2007). Characteristics of movement of the lips, tongue and velum during a bilabial plosiveA noninvasive study using a magnetic resonance imaging movie. The Angle Orthodontist, 77, 612618. Jacoby, L. L. (1983). Perceptual enhancement: Persistent effects of an experience. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 9, 2138. Jacoby, L. L., & Dallas, M. (1981). On the relationship between autobiographical memory and perceptual learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 110, 306340. Jacoby, L. L., & Kelley, C. M. (1987). Unconscious influences of memory for a prior event. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 13, 314336. Jacoby, L. L., Kelley, C. M., Brown, J., & Jasechko, J. (1989). Becoming famous overnight: Limits on the ability to avoid unconscious influences of the past. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 326338. Jacoby, L. L., & Whitehouse, K. (1989). An illusion of memory: False recognition influenced by unconscious perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118, 126135. Jacoby, L. L., Woloshyn, V., & Kelley, C. M. (1989). Becoming famous without being recognized: Unconscious influences of memory produced by dividing attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118, 115125. Kunst-Wilson, W. R., & Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Affective discrimination of stimuli that cannot be recognized. Science, 207, 557558. MacLeod, C. M. (1991). Half a century of research on the Stroop Effect: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 109, 163203. Mandler, G. (1980). Recognizing: The judgment of previous occurrence. Psychological Review, 87, 252271. Mandler, G., Nakamura, Y., & Van Zandt, B. J. S. (1987). Nonspecific effects of exposure on stimuli that cannot be recognized. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13, 646648. Matlin, M. W. (1970). Response competition as a mediating factor in the frequencyaffect relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16, 536552.

338

Emotion Review Vol. 2 No. 4

Matlin, M. W. (1971). Response competition, recognition, and affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 19, 293300. Miyake, A., Emerson, M. J., Padilla, F., & Ahn, J. (2004). Inner speech as a retrieval aid for task goals: The effects of cue type and articulatory suppression in the random task cuing paradigm. Acta Psychologica, 115, 123142. Monahan, J. L., Murphy, S. T., & Zajonc, R. B. (2000). Subliminal mere exposure: Specific, general and diffuse effects. Psychological Science, 11, 462467. Moreland, R. L. (1985). Birth order. In A. Kuper & J. Kuper (Eds.), The social science encyclopedia. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Moreland, R. L., & Beach, S. R. (1992). Exposure effects in the classroom: The development of affinity among students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28, 255276. Moreland, R. L., & Zajonc, R. B. (1976). A strong test of exposure effects. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 12, 170179. Moreland, R. L., & Zajonc, R. B. (1977). Is stimulus recognition a necessary condition for the occurrence of exposure effects? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 191199. Moreland, R. L., & Zajonc, R. B. (1979). Exposure effects may not depend on stimulus recognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 10851089. Moreland, R. L., & Zajonc, R. B. (1982). Exposure effects in person perception: Familiarity, similarity, and attraction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 18, 395415. Newell, B. R., & Bright, J. E. H. (2001). The relationship between the structural mere exposure effect and the implicit learning process. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 54, 10871104. Newell, B. R., & Bright, J. E. H. (2003). The subliminal mere exposure effect does not generalize to structurally related stimuli. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 57, 6168. Newell, B. R., & Shanks, D. R. (2007). Recognizing what you like: Examining the relation between the mere-exposure effect and recognition. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19, 103118. Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). Embodying emotion. Science, 316, 10021005. Niedenthal, P. M., Barsalou, L. W., Winkielman, P., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2005). Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personality and Social Psychological Review, 9, 184211. Niedenthal, P. M., Winkielman, P., Mondillon, L., & Vermeulen, N. (2009). Embodiment of emotional concepts: Evidence from EMG measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 11201136. Nuttin, J. M. (1985). Narcissism beyond Gestalt and awareness: The name letter effect. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15, 353361. Phaf, R. H., & Roteveel, M. (2005). Affective modulation of recognition bias. Emotion, 5, 309318. Rajecki, D. W. (1982). Attitudes: Themes and advances. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer. Reber, R., & Schwarz, N. (1999). Effects of perceptual fluency on judgments of truth. Consciousness and Cognition, 8, 338342. Reber, R., Schwarz, N., & Winkielman, P. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceivers processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 364382. Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (1998). Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychological Science, 9, 4548. Reber, R., Wurtz, P., & Zimmermann, T. D. (2004). Exploring fringe consciousness: The subjective experience of perceptual fluency and its objective bases. Consciousness and Cognition, 13, 4760. Saegert, S. C., & Jellison, J. M. (1970). Effects of initial level of response competition and frequency of exposure on liking and exploratory behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16, 553558. Saegert, S., Swap, W. C., & Zajonc, R. B. (1973). Exposure, context, and interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25, 234242.

Scarborough, D. L., Cortese, C., & Scarborough, H. S. (1977). Frequency and repetition effects in lexical memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 3, 117. Schubert, T. W., & Semin, G. R. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 11351141. Seamon, J. G., Brody, N., & Kauff, D. M. (1983). Affective discrimination of stimuli that are not recognized: Effects of shadowing, masking, and cerebral laterality. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 9, 544555. Seamon, J. G., Marsh, R. L., & Brody, N. (1984). Critical importance of exposure duration for affective discrimination of stimuli that are not recognized. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 10, 465469. Semin, G. R., & Smith, E. R. (2008). Introducing embodied grounding. In G. R. Semin & E. R. Smith (Eds.), Embodied grounding: Social, cognitive, affective, and neuroscientific approaches (pp. 18). New York: Cambridge University Press. Smith, G. F., & Dorfman, D. D. (1975). The effect of stimulus uncertainty on the relationship between frequency of exposure and liking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 553558. Stang, D. J. (1974). Methodological factors in mere exposure research. Psychological Bulletin, 81, 10141025. Stang, D. J. (1975). Effects of mere exposure on learning and affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 712. Stang, D. J. (1976). A critical examination of the response competition hypothesis. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 7, 530532. Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12, 242248. Topolinski, S. (in press). Moving the eye of the beholder: Motor components in vision determine aesthetic preference. Psychological Science. Topolinski, S., Likowski, K. U., Weyers, P., & Strack, F. (2009). The face of fluency: Semantic coherence automatically elicits a specific pattern of facial muscle reactions. Cognition & Emotion, 23, 260271. Topolinski, S., & Reber, R. (2010). Immediate truthTemporal contiguity between a cognitive problem and its solution determines experienced veracity of the solution. Cognition, 114, 117122. Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2009a). Motormouth: Mere exposure depends on stimulus-specific motor simulations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 423433. Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2009b). Scanning the fringe of consciousness: What is felt and what is not felt in intuitions about semantic coherence. Consciousness and Cognition, 18, 608618. Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2009c). The analysis of intuition: Processing fluency and affect in judgements of semantic coherence. Cognition & Emotion, 23, 14651503. Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2009d). The architecture of intuition: Fluency and affect determine intuitive judgments of semantic and visual coherence, and of grammaticality in artificial grammar learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 138, 3963. Topolinski, S., & Strack, F. (2010). False fame preventedavoiding fluencyeffects without judgmental correction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(5), 721733. Tucker, M., & Ellis, R. (1998). On the relations between seen objects and components of potential actions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human perception and performance, 24, 830846. Unkelbach, C. (2007). Reversing the truth effect: Learning the interpretation of processing fluency in judgments of truth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 33, 219230. Van den Bergh, O., Vrana, S., & Eelen, P. (1990). Letters from the heart: Affective categorization of letter combinations in typists and nontypists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16, 11531161.

Moreland & Topolinski

Mere Exposure

339

Whittlesea, B. W. A. (1993). Illusions of familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19, 12351253. Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 9, 625636. Wilson, W. R. (1979). Feeling more than we can know: Exposure effects without learning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 811821. Winkielman, P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2001). Mind at ease puts a smile on the face: Psychophysiological evidence that processing facilitation leads to positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 9891000. Yang, S., Gallo, D., & Beilock, S. L. (2009). Embodied memory judgments: A case of motor fluency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 35, 13591365. Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Monographs, 9, 127. Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35, 151175. Zajonc, R. B. (1984). On the primacy of affect. American Psychologist, 39, 117123.

Zajonc, R. B. (1985). Emotion and facial efference: A theory reclaimed. Science, 228, 1521. Zajonc, R. B. (2001). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Psychological Science, 10, 224228. Zajonc, R. B., Berbaum, M. L., Hamill, R., Moreland, R. L., & Akeju, S. A. (1980). Family factors and the intellectual performance of Nigerian eleven-year-olds. West African Journal of Educational and Vocational Measurement, 5, 1926. Zajonc, R. B., & Burnstein, E. (1965). The learning of balanced and unbalanced social structures. Journal of Personality, 33, 153163. Zajonc, R. B., Markus, G. B., Berbaum, M. L., Bargh, J., & Moreland, R. L. (1991). One justified criticism plus three flawed analyses equals two unwarranted conclusions: A reply to Retherford and Sewell. American Sociological Review, 56, 159165. Zajonc, R. B., & Markus, H. (1984). Affect and cognition: The hard interface. In C. E. Izard, J. Kagan & R. B. Zajonc (Eds.), Emotions, cognition, and behavior (pp. 73102). New York: Cambridge University Press. Zajonc, R. B., Murphy, S. T., & Inglehart, M. (1989). Feeling and facial efference: Implications of the vascular theory of emotion. Psychological Review, 96, 395416.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- JLS JLPT N1-N5Document2 pagesJLS JLPT N1-N5Shienthahayoyohayoha100% (1)

- Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya: FeaturesDocument8 pagesVidura, Uddhava and Maitreya: FeaturesNityam Bhagavata-sevayaNo ratings yet

- Global Economy and Market IntegrationDocument6 pagesGlobal Economy and Market IntegrationJoy SanatnderNo ratings yet

- N.E. Essay Titles - 1603194822Document3 pagesN.E. Essay Titles - 1603194822კობაNo ratings yet

- SSP1 Speech - ExamDocument3 pagesSSP1 Speech - ExamJohn Carl SuganNo ratings yet

- Editorial Board 2023 International Journal of PharmaceuticsDocument1 pageEditorial Board 2023 International Journal of PharmaceuticsAndrade GuiNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Hospitality Management: Po-Tsang Chen, Hsin-Hui HuDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Hospitality Management: Po-Tsang Chen, Hsin-Hui HuNihat ÇeşmeciNo ratings yet

- Laser Coaching: A Condensed 360 Coaching Experience To Increase Your Leaders' Confidence and ImpactDocument3 pagesLaser Coaching: A Condensed 360 Coaching Experience To Increase Your Leaders' Confidence and ImpactPrune NivabeNo ratings yet

- Periodic Rating FR Remarks Periodic Rating 1 2 3 4 1 2: Elementary School ProgressDocument8 pagesPeriodic Rating FR Remarks Periodic Rating 1 2 3 4 1 2: Elementary School ProgresstotChingNo ratings yet

- Eligible Candidates List For MD MS Course CLC Round 2 DME PG Counselling 2023Document33 pagesEligible Candidates List For MD MS Course CLC Round 2 DME PG Counselling 2023Dr. Vishal SengarNo ratings yet

- Devendra Bhaskar House No.180 Block-A Green Park Colony Near ABES College Chipiyana VillageDocument3 pagesDevendra Bhaskar House No.180 Block-A Green Park Colony Near ABES College Chipiyana VillageSimran TrivediNo ratings yet

- School Climate and Academic Performance in High and Low Achieving Schools: Nandi Central District, KenyaDocument11 pagesSchool Climate and Academic Performance in High and Low Achieving Schools: Nandi Central District, Kenyaزيدون صالحNo ratings yet

- PIT-AR2022 InsidePages NewDocument54 pagesPIT-AR2022 InsidePages NewMaria Francisca SarinoNo ratings yet

- Day 19 Lesson Plan - Theme CWT Pre-Writing 1Document5 pagesDay 19 Lesson Plan - Theme CWT Pre-Writing 1api-484708169No ratings yet

- Rajveer Kaur Ubee: Health TEAMDocument2 pagesRajveer Kaur Ubee: Health TEAMRajveer Kaur ubeeNo ratings yet

- EAPP DebateDocument3 pagesEAPP DebateAyessa JordanNo ratings yet

- Principles & Procedures of Materials DevelopmentDocument66 pagesPrinciples & Procedures of Materials DevelopmenteunsakuzNo ratings yet

- Bab II ProposalDocument4 pagesBab II ProposalMawaddah HidayatiNo ratings yet

- SMK Tinggi Setapak, Kuala Lumpur Kehadiran Ahli Ragbi Tahun 2011Document4 pagesSMK Tinggi Setapak, Kuala Lumpur Kehadiran Ahli Ragbi Tahun 2011studentmbsNo ratings yet

- Teaching Physical Education Lesson 1Document2 pagesTeaching Physical Education Lesson 1RonethMontajesTavera100% (1)

- Department of Education: Solves Problems Involving Permutations and CombinationsDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Solves Problems Involving Permutations and CombinationsJohn Gerte PanotesNo ratings yet

- DR Cheryl Richardsons Curricumlum Vitae-ResumeDocument4 pagesDR Cheryl Richardsons Curricumlum Vitae-Resumeapi-119767244No ratings yet

- National Standards For Foreign Language EducationDocument2 pagesNational Standards For Foreign Language EducationJimmy MedinaNo ratings yet

- Osborne 2007 Linking Stereotype Threat and AnxietyDocument21 pagesOsborne 2007 Linking Stereotype Threat and Anxietystefa BaccarelliNo ratings yet

- Resume Format: Melbourne Careers CentreDocument2 pagesResume Format: Melbourne Careers CentredangermanNo ratings yet

- Aiming For Integrity Answer GuideDocument4 pagesAiming For Integrity Answer GuidenagasmsNo ratings yet

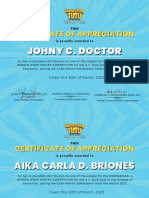

- Certificate of AppreciationDocument114 pagesCertificate of AppreciationSyrus Dwyane RamosNo ratings yet

- Babcock University Bookshop An Babcock University BookshopDocument11 pagesBabcock University Bookshop An Babcock University BookshopAdeniyi M. AdelekeNo ratings yet

- Marissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Document9 pagesMarissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Allysha TifanyNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Webquest RubricDocument1 pageClimate Change Webquest Rubricapi-3554784500% (1)