Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Bank of New York Uses ITIL To Troubleshoot

Uploaded by

guruvietnamOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Bank of New York Uses ITIL To Troubleshoot

Uploaded by

guruvietnamCopyright:

Available Formats

How Bank of New York Uses ITIL to Troubleshoot

( Page 1 of 6 ) Technology managers at the Bank of New York thought they were doing a good job of running the information systems, networks and other services the company supplies to its internal and external customers. But good wasn't good enough. They couldn't back up their assessment with metrics. "When senior business managers asked senior I.T. managers: 'How are you guys doing? How is the process working? Show me some measurements,' we were not able to supply that," recalls Joseph Gallagher, vice president of I.T. process implementation at the Bank of New York. Those measurements, which have since been adopted, include statistics such as the number of service outages and their severity as well as the amount of time it takes to restore service. That's why Bank of New York's technology managers turned to the Information Technology Infrastructure Library, or ITIL, a series of publications written by the United Kingdom's Office of Government Commerce in the 1980s that describe best practices for managing technology infrastructuresuch as specifying that you should have a central information repository for tracking service problems such as server crashes or network outages. It provides a "feedback loop" to reduce or eliminate future incidents by collecting and analyzing the source of incidents and taking corrective action before a similar incident reoccurs. Advocates see ITIL as a way to boost discipline in technology operations, and adopt a common vocabulary for discussing quality of service and establishing metrics. The library, which is available in print, on a CD-ROM or via an intranet license, provides guidance on how to approach eight key processes, including service delivery, service support, security management and software asset management. "ITIL was specifically created because of the recognition that good quality software and systems don't automatically provide good quality services to customers," says David Cannon, HewlettPackard's I.T. service management practice principal and a consultant working on behalf of the British government to refresh ITIL. Cannon compares the situation to someone who owns a $100,000 Mercedeswith the best safety and performance systems that money can buy. "The problem is that I have never taken a driving lesson in my life and don't have a license. As a result, I stick to the back roads and drive at least 10 mph below the speed limit ... I never get anywhere on time," he says. U.K. technology managers apparently were in the slow lane, too, when they purchased software and hardware to automate services back in the 1980s, yet did not get optimal performance. So, the U.K. recognized the need for a manual to help get its operations running better.

Now, that manual is being used by some of the world's largest companies as a guide to better information-technology management. Earlier this year, for instance, Hewlett-Packard announced that General Motors had retained HP Services to use ITIL as a building block for the deployment of GM's next-generation outsourcing modelto verify that I.T. vendors meet service levels. As many as 75% of the Fortune 100 are among those companies embracing ITIL for an assortment of reasons, says Jack Probst, an executive consultant at Pink Elephant, a firm that provides ITIL education, conferences and consulting services to companies such as Nationwide Insurance, Bank of Montreal and BP. Two Pink Elephant employees are also working as consultants on the project to update the library. When a Problem Isn't a Problem When the Bank of New York acquired Pershing, a financial clearinghouse for securities and other financial transactions, in May 2003, both organizations were working on improving I.T. service support through ITIL; the Bank of New York initially focused on change and incident management and the Pershing subsidiary zeroed in on incident and problem management. Why? "They were the ones [that gave us] the most painfrom a business perspective," says Gallagher, who was then project leader for the efforts to implement incident and problem management at Pershing. Today, the Bank of New York, including its Pershing subsidiary, defines a major incident as any issue that causes a disruption of service to three or more internal or external customers. It could involve, say, a disabled mainframe or a server crash that makes it impossible for employees to access a software application. Previously, each group within the I.T. organization used its own method to manage incidents, making it difficult to measure the effectiveness of the process, according to Gallagher. "Also, communication of the status of an incident as it was under investigation was limited and inconsistent; many managers were not aware of the progress of incident diagnosis and resolution," he explains. At the bank, problem management refers to the process of investigating and verifying the cause of incidents, such as a server outage, and then assessing whether the incident is part of a larger pattern that requires a long-term fix or other remediation, such as notifying the server manufacturer about a possible product defect. Taking a cue from ITIL, Gallagher stresses that the terms "incident" and "problem" are not interchangeable. In ITIL lingo, an incident refers to a service disruption, e.g., the actual event. The "problem" refers to why an incident happened in the first place. But isn't this splitting hairs? Gallagher sees it this way: An "incident" is something that technology managers must react to as quickly as possible to ensure that service is restored. If you try to investigate the cause of an incident while attempting to restore service, Gallagher says your immediate restoration work won't get top priorityand, as a result, may take longer. Oftentimes, a company hit with a major service outage due to systems changes will adopt the library's processes for filtering and managing changes to avoid disruptions in service. "What

seems to resonate with everyone is that [ITIL] is best practices-based; it provides guidance without specific direction. So, it provides flexibility in how you implement the framework," says Probst. What's the downside? Don't expect change to happen quickly. "A lot of executives want to know why it's going to take a year or 18 months" to improve a process, Probst says. The reason why it takes so long: Managing services consistently throughout an organization may require employees to change the way they work. "People have to give up old ways." Probst adds. "You're changing culture and the organization." Gaining Traction Proponents of ITIL say the practice is designed to improve consistency in operations from one unit or division to another. "We used to have four different service desks, and everyone did things their own way. There was no commonality as to what was an incident, what was a problem. We didn't have any tools to track this," says Pershing's chief information officer, Suresh Kumar, of his organization. At Pershing, one service desk is dedicated to handling calls from internal business users and another from external customers; the other service desks are dedicated to taking calls from a specific segment of the company's customer base. While Pershing still has four service desks, they all use the same definitions to describe a particular problem. "ITIL recommends that an organization follow the same processes, start to finish. Regardless of service or customer, the activities for incident should be the same," Gallagher explains. "People get into their heads that this is the process, it becomes institutionalized, it becomes repeatable." Following the same definitions provides another benefit. "It gives our business a sense that we're working on the highest priority incidents. That we're focusing our resources," Gallagher explains. "It gives us the ability to measure the time to resolve those incidents, and look for ways to improve and reduce the time to resolve [them]." Incident and problem management are popular ITIL practices, says HP's Cannon. "When things break, it causes downtime to the business. There's a certain amount of urgency to get that problem fixed." At the Bank of New York, each incident is assigned a severity number, from one to four, with number one representing an incident that has significant impact on the services offered to the business and customers. Four is assigned to minor incidents that do not need immediate attention. ITIL recommends the same numbering scheme. ITIL also recommends that the service desk "own" every incident created. The Bank of New York follows this guideline, making an exception for its highest priority incidents affecting business or customers. In those cases, the bank assigns incident "ownership" to the service owner within I.T. The service desk then acts as incident coordinator, setting up telephone conference calls, updating the incident ticket, paging managers and keeping customers updated, according to

Gallagher. "This distribution of responsibilities during high priority incidents ensures that all I.T. staff are focused on incident resolution," he says. By breaking up these duties, the Bank of New York makes sure that one person is not responsible for both fixing an incident and alerting customers about the service disruption. Managing Problems Once an incident is resolved at the Bank of New York, the "problem management" process kicks in with a so-called root cause analysis. This phase involves a more in-depth investigation into the cause of an incident; those findings are then vetted and corrective actions are taken to prevent an incident from reoccurring, according to Gallagher. The bank has realized benefits from this effort. During 2005, Pershing recorded an average of 65 so-called severity-one incidents each month. For the first five months of 2006, the number dropped to 51, a 21.5% decline from 2005. The cost to resolve the most severe incidents declined from an average of about $1,600 per incident in July 2004, to about $200 per incident in January 2006, according to Gallagher. The bank has not performed a return-on-investment assessment for the ITIL initiative, he says. "ITIL has allowed us to streamline processes and advance the culture toward providing exceptional service." The cornerstone of the Bank of New York's problem management efforts has been the establishment of a Root Cause Analysis (RCA) Committee, comprised of about 10 senior managers who represent a cross-section of I.T. groups. Every business day, the committee reviews and verifies the cause of a severity-one incident. That review process, first initiated at the Pershing subsidiary, is now being rolled throughout the Bank of New York, according to company executives. Here, the Bank of New York has gone over and above what's called for in ITIL. Each severityone incident is assigned to a root cause analysis "owner," potentially any one of Bank of New York's technology employees. The root cause analysis owner is then asked to investigate an incident and report back to the RCA Committee within five business days. Promptly at 9 a.m. each business day, the RCA Committee convenes. Those on-site gather at a Bank of New York conference room; others dial in to a telephone conference line. On each agenda: two to five incidents; each "owner" is allocated time to discuss his investigation into a particular service disruption and explain what he thinks caused the problem. From there, the owner fields questions from committee members, who may agree or challenge the owner's assessment and direct him to gather more information. About one-third of the cases are kicked back for additional research, according to Gallagher. "If you are not sure of your root cause, how can you be sure of your corrective action?" he asks.

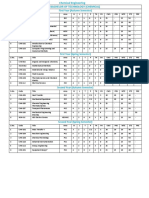

Out of a monthly average of 65 severity-one incidents reported in 2005, 15% were attributed to human error, 13% to a program bug, 11% to vendor issues, 11% to process problems, 8% to software and 8% to inaccurate technical analysis; 13% were due to unknown reasons. By collecting in-depth, consistent information about incidents and their causes, the technology team is able to determine whether a problem is an isolated incident or part of a larger trend, according to Pershing's technology managers. If it's part of a larger trend, a task force is created to investigate the cause and recommend an action plan. This was the case with printers owned by Pershing and located at customers' premises. These printers, used to prepare daily reports about transactions, account balances, etc., were going offline without explanation. Once Pershing started to log each disruption as an incident, the financial institution discovered there were 600 to 700 printer-related incidents each month. CIO Kumar assigned a team of technology workers to use Six Sigma methodology to investigate the printer problems. The team discovered that "a large percentage of incidents were due to a network communication issue," Gallagher says. After further investigation, Pershing learned that a software patch would remediate most of the incidents. Today, there are about 100 printer incidents a month that are attributed to typical issues such as paper jams or spooling errors. "Nothing stands out as a major repeatable incident now," Gallagher says. Keep in mind: ITIL does not offer specifics on how to fix printers or any other equipment. "What ITIL provides is a process to classify incidents in a manner to ensure they are accurately assigned to the appropriate support group within the I.T. organization," Gallagher says. Getting Tools To collect and analyze information about service disruptions, you need tools. And Gallagher advises that those tools be automated whenever possible. At Pershing, the internal software developers built an application, called OmniMetrics, that imports information from its BMC Remedy help-desk application database and other sources to create performance scorecards. These scorecards show the total number of severity-one incidents by month, group or manager; they also assess each tech team's responses to incidents, thus giving an overall picture of performance. For organizations looking to implement ITIL and measure performance, Gallagher has some advice: "Don't promise improvement until you have a real good historical baseline." Case in point: Before June 2004, Pershing had no baseline metrics for measuring severity-one incidents. When it started to develop processes for managing incidents and problems, the definition of a severity-one incident changed, and more incidents were reported. Why? The company saw the value of reporting and tracking outages, Gallagher says. Incidents such as missing a service level agreement during the overnight batch cyclenot originally includedwere added.

By December 2004in time for the 2005 calendar yearPershing locked down its definition of severe service outages. "We wanted a 12-month period of saying, 'This is how the organization performs without any changes to the criteria.' That was our baseline," Gallagher explains. Once Pershing collected and analyzed metrics, the technology organization could create scorecards, another key tenet of ITIL, to show the performance of technology servicesand, in effect, the performance of managers responsible for those particular services, or service owners, according to CIO Kumar. One surprise: When Pershing created a catalog listing all technology services, Kumar says he and his team discovered that in some cases, there were multiple owners of a service. And in other cases, there were no owners. Plus, a service owner might not necessarily know who the customer of his service was. To improve accountability, Pershing has identified one service owner for each service, in a process that's still evolving throughout the Bank of New York, according to Kumar. The CIO provided this example: Let's say there's an incident with a printing service that could be due to any of several reasonseither an application, network, firewall or server failing to work properly. Previously, the tech team would view the problem as either a hardware or software problem. Someone using the service, though, would view it as a printer problem, which is how the technology team now approaches its job. Publishing a monthly scorecardand identifying services and service ownersincreased the transparency of technology operations and triggered an immediate improvement in operations, Kumar says. "We didn't have to yell at people," he says. "We didn't have to offer any incentives. It just goes to show that when everyone comes to work, they love to do the best they can. But lack of information doesn't give them the knowl edge to see performance."

You might also like

- The Chocolate Elephant Part 1: Business Process Management and IT Service ManagementFrom EverandThe Chocolate Elephant Part 1: Business Process Management and IT Service ManagementNo ratings yet

- Itil ®as An Inspiration For Governing A Small IT Consultancy's Support BusinessDocument7 pagesItil ®as An Inspiration For Governing A Small IT Consultancy's Support BusinessLuis Martin-SantosNo ratings yet

- Probing The Knowledge Market: KM For Legal AppsDocument4 pagesProbing The Knowledge Market: KM For Legal AppsMilica BjelicNo ratings yet

- Cost Estimation in Agile Software Development: Utilizing Functional Size Measurement MethodsFrom EverandCost Estimation in Agile Software Development: Utilizing Functional Size Measurement MethodsNo ratings yet

- Using Process Mining For ITIL Assessment A Case Study With Incident ManagementDocument17 pagesUsing Process Mining For ITIL Assessment A Case Study With Incident ManagementelfowegoNo ratings yet

- Implementation of a Central Electronic Mail & Filing StructureFrom EverandImplementation of a Central Electronic Mail & Filing StructureNo ratings yet

- Implementing ITIL For Incident ManagementDocument17 pagesImplementing ITIL For Incident ManagementUday Kumar100% (1)

- Incident Management Process Guide For Information TechnologyFrom EverandIncident Management Process Guide For Information TechnologyNo ratings yet

- ITIL+Service Operation 1203Document49 pagesITIL+Service Operation 1203Андрей ИвановNo ratings yet

- Servicing Itsm: A Handbook of Service Descriptions for It Service Managers and a Means for Building ThemFrom EverandServicing Itsm: A Handbook of Service Descriptions for It Service Managers and a Means for Building ThemRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- A Fool With A Tool Is Still A FoolDocument27 pagesA Fool With A Tool Is Still A Foolajv_gomesNo ratings yet

- Digitalization Cases Vol. 2: Mastering Digital Transformation for Global BusinessFrom EverandDigitalization Cases Vol. 2: Mastering Digital Transformation for Global BusinessNo ratings yet

- Doing IT Right - IT Service Management and ITIL White Paper by Kirk HolmesDocument5 pagesDoing IT Right - IT Service Management and ITIL White Paper by Kirk HolmesKirk HolmesNo ratings yet

- ITIL SuccessDocument9 pagesITIL SuccessgieblackgionoNo ratings yet

- Rfcs Resulting From Known ErrorsDocument14 pagesRfcs Resulting From Known ErrorsEternal Pharma chemNo ratings yet

- Facilities Management - Moving Towards ITILDocument4 pagesFacilities Management - Moving Towards ITILTOPdesk100% (1)

- Virtual Service Desk The Third Organizational Option Described by ITIL Is That of A Virtual Service Desk. This OptionDocument3 pagesVirtual Service Desk The Third Organizational Option Described by ITIL Is That of A Virtual Service Desk. This OptionMaheedhar HmpNo ratings yet

- ITIL Incident Management 101Document6 pagesITIL Incident Management 101Sushmita IyengarNo ratings yet

- What Is The Importance of ITSM Software?: 1. Improve EfficiencyDocument8 pagesWhat Is The Importance of ITSM Software?: 1. Improve EfficiencyquinNo ratings yet

- Thesis ItilDocument6 pagesThesis Itilashleythomaslafayette100% (2)

- Barriers To Implementing ITIL-A Multi-Case Study On The Service-Based IndustryDocument20 pagesBarriers To Implementing ITIL-A Multi-Case Study On The Service-Based IndustryxfireloveNo ratings yet

- Value of ITIL Process FrameworkDocument9 pagesValue of ITIL Process FrameworkAhmadNo ratings yet

- Embrace The Inevitable - Six Imperatives To Prepare Your Company For Cloud ComputingDocument4 pagesEmbrace The Inevitable - Six Imperatives To Prepare Your Company For Cloud ComputingswainanjanNo ratings yet

- Trend AnalysisDocument5 pagesTrend AnalysisvijayskbNo ratings yet

- Answer1:: Name: Said Amin Shah ROLL NO:9955Document3 pagesAnswer1:: Name: Said Amin Shah ROLL NO:9955momin khanNo ratings yet

- Itil Best Practices With Oracle Enterprise Manager 10 and Oracle Peoplesoft Help DeskDocument19 pagesItil Best Practices With Oracle Enterprise Manager 10 and Oracle Peoplesoft Help Desksuwei1977No ratings yet

- ITIL Version 3 Best Practices: Safari Books Online For GovernmentDocument8 pagesITIL Version 3 Best Practices: Safari Books Online For GovernmentPrasetyo BawonoNo ratings yet

- ITIL: Pragmatic and SimpleDocument13 pagesITIL: Pragmatic and SimpleGeir IseneNo ratings yet

- Itil and TOGAF 9.1: Two Frameworks: Tom Van Sante and Jeroen Ermers, KPN IT SolutionsDocument12 pagesItil and TOGAF 9.1: Two Frameworks: Tom Van Sante and Jeroen Ermers, KPN IT Solutionsarvind ronNo ratings yet

- Accelerating Problem ResolutionDocument7 pagesAccelerating Problem ResolutionxthomNo ratings yet

- ITIL and Security Management OverviewDocument15 pagesITIL and Security Management OverviewHarpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- Oracle Enterprise Manager 11g: An Oracle White Paper April 2010Document23 pagesOracle Enterprise Manager 11g: An Oracle White Paper April 2010dennis_denjenNo ratings yet

- Defiinisi ProblemsDocument4 pagesDefiinisi ProblemsDiaz MahardikaNo ratings yet

- White Paper Togaf 9 Itil v3 Sept09Document16 pagesWhite Paper Togaf 9 Itil v3 Sept09Felipe Alzate RoldanNo ratings yet

- Important Itsm PDFDocument12 pagesImportant Itsm PDFJohn_FlagmanNo ratings yet

- Business ProcessDocument8 pagesBusiness ProcessDebabrat MishraNo ratings yet

- ITIL® Implementation in Your IT Organization: White PaperDocument9 pagesITIL® Implementation in Your IT Organization: White PaperAbdelfattahHabibNo ratings yet

- ServiceNow - ITILDocument3 pagesServiceNow - ITILvenkiNo ratings yet

- Ge Itil Six Sigma ItsmDocument12 pagesGe Itil Six Sigma ItsmmzagorskiNo ratings yet

- Continuing Care Report - Realizing Your Investment in Technology and IT ServicesDocument9 pagesContinuing Care Report - Realizing Your Investment in Technology and IT ServicesTechcare IT ServicesNo ratings yet

- Pink Elephant SM Implementation RoadmapDocument24 pagesPink Elephant SM Implementation Roadmapkhanhnc2No ratings yet

- How IT Is Reinventing Itself As A Strategic Business PartnerDocument3 pagesHow IT Is Reinventing Itself As A Strategic Business PartnerJoana ReisNo ratings yet

- ITil Best PracticeDocument42 pagesITil Best PracticeNader HanyNo ratings yet

- Mis 2Document8 pagesMis 2razi87No ratings yet

- Cs Santander 2012Document3 pagesCs Santander 2012Giriprasad GunalanNo ratings yet

- Ti 2013080613574612 PDFDocument7 pagesTi 2013080613574612 PDFIban SakuragiNo ratings yet

- Products Documents 02-45-200245 200245Document4 pagesProducts Documents 02-45-200245 200245Lokanatha ReddyNo ratings yet

- ITIL® Evolution: From Processes To Practices: Mark SmalleyDocument6 pagesITIL® Evolution: From Processes To Practices: Mark SmalleyCarlos sanchezNo ratings yet

- The Itil FrameworkDocument3 pagesThe Itil Frameworkinsomniac432No ratings yet

- ITIL The Basics PDFDocument5 pagesITIL The Basics PDFdeolah06No ratings yet

- Why New Technologies FailDocument9 pagesWhy New Technologies FailFasika BeteNo ratings yet

- Roundup of Banking and Investment Services ResearchDocument12 pagesRoundup of Banking and Investment Services Researcha.asodekarNo ratings yet

- Valerie Arraj, Managing Director, Compliance Process Partners, LLCDocument5 pagesValerie Arraj, Managing Director, Compliance Process Partners, LLCmikeolmonNo ratings yet

- Itil Benefits To The Business: A Joint Research Project From Global Knowledge and HDIDocument13 pagesItil Benefits To The Business: A Joint Research Project From Global Knowledge and HDI3loahNo ratings yet

- STC-4 0Document30 pagesSTC-4 0sksnoopyNo ratings yet

- Digital Transformation Is Not About TechnologyDocument4 pagesDigital Transformation Is Not About TechnologyCorinaNo ratings yet

- Itsm Process Maps Whitepaper 6.08 WebDocument20 pagesItsm Process Maps Whitepaper 6.08 Webrohit.joshi4u100% (2)

- The Role of ITIL in Building The Enterprise of The FutureDocument3 pagesThe Role of ITIL in Building The Enterprise of The FutureMilica BjelicNo ratings yet

- Service SupportDocument528 pagesService Supportcarlos.f.farnesiNo ratings yet

- Divorce Forms No Children - July 20172Document51 pagesDivorce Forms No Children - July 20172Last Place GarageNo ratings yet

- Aquaculture in Victoria PDFDocument58 pagesAquaculture in Victoria PDFirkeezNo ratings yet

- Legal Memorandum For ProsecutionDocument5 pagesLegal Memorandum For ProsecutionAnge Buenaventura Salazar88% (8)

- Carburattor Set UpDocument3 pagesCarburattor Set Uppalotito_eNo ratings yet

- Hydraulic Pump Unit 1 15Document2 pagesHydraulic Pump Unit 1 15azry_alqadryNo ratings yet

- Instruction Manual: Weatherguide System Indoor/Outdoor ThermometerDocument8 pagesInstruction Manual: Weatherguide System Indoor/Outdoor ThermometerCompras FisicoquimicoNo ratings yet

- Speech Health: The New Normal After Pandemic Tittle: "Living Peace in The New Normal"Document2 pagesSpeech Health: The New Normal After Pandemic Tittle: "Living Peace in The New Normal"Nia GallaNo ratings yet

- Robots, Love & Sex: The Ethics of Building A Love MachineDocument12 pagesRobots, Love & Sex: The Ethics of Building A Love MachineGina SmithNo ratings yet

- Community Directory (May 2023)Document32 pagesCommunity Directory (May 2023)The Livingston County NewsNo ratings yet

- Use of Alternative Energy Sources For The Initiation and Execution of Chemical Reactions and ProcessesDocument21 pagesUse of Alternative Energy Sources For The Initiation and Execution of Chemical Reactions and ProcessesNstm3No ratings yet

- Final Exam Review Notes PDFDocument160 pagesFinal Exam Review Notes PDFDung TranNo ratings yet

- IIT Roorkee Programme Structure CHeDocument4 pagesIIT Roorkee Programme Structure CHeabcNo ratings yet

- Gazi Abdur Rakib BiodataDocument2 pagesGazi Abdur Rakib Biodataগাজী আব্দুর রাকিবNo ratings yet

- Topic 8 QuestionsDocument90 pagesTopic 8 QuestionsRaiannur RohmanNo ratings yet

- Kasus Ke 10 (Inggris)Document5 pagesKasus Ke 10 (Inggris)Fauzan AdvantageNo ratings yet

- Reciprocating Cryogenic Pumps & Pump Installations FinalDocument19 pagesReciprocating Cryogenic Pumps & Pump Installations Finaldaimon_pNo ratings yet

- Lecture 01 (Basics) ME141 PDFDocument18 pagesLecture 01 (Basics) ME141 PDFAlteaAlNo ratings yet

- Finger Painting (Therapeutic Skills)Document12 pagesFinger Painting (Therapeutic Skills)Ellyn GraceNo ratings yet

- Describing People Greyscale KeyDocument3 pagesDescribing People Greyscale KeyNicoleta-Cristina SavaNo ratings yet

- Pruritus in Kidney DiseaseDocument10 pagesPruritus in Kidney DiseaseBrian CastanaresNo ratings yet

- Amtech ProDesign Product GuideDocument3 pagesAmtech ProDesign Product GuideShanti Naidu0% (1)

- Introductory Statistics: (Ding Et Al., 2018)Document3 pagesIntroductory Statistics: (Ding Et Al., 2018)Kassy LagumenNo ratings yet

- The Azf Factory ExplosionDocument29 pagesThe Azf Factory ExplosionHitakshi AroraNo ratings yet

- (PDF) Pass Through Panic: Freeing Yourself From Anxiety and FearDocument1 page(PDF) Pass Through Panic: Freeing Yourself From Anxiety and FearmilonNo ratings yet

- Vanessa Booklet VAARSDocument16 pagesVanessa Booklet VAARSKarla PrezNo ratings yet

- Unit 12 Asking For The BillDocument3 pagesUnit 12 Asking For The BillPan DaNo ratings yet

- DEVELOPMENT, UNDERDEVELOPMENT, POVERTY - Sample Research Proposal - SMUDocument6 pagesDEVELOPMENT, UNDERDEVELOPMENT, POVERTY - Sample Research Proposal - SMUEira ShahNo ratings yet

- Ficha Solarnova 550W - EngDocument2 pagesFicha Solarnova 550W - EngHugo AngelesNo ratings yet

- The Best Broccoli Cheese Soup (Better-Than-Panera Copycat) - Averie CooksDocument1 pageThe Best Broccoli Cheese Soup (Better-Than-Panera Copycat) - Averie CooksEmily WillisNo ratings yet

- Mil PRF 680CDocument12 pagesMil PRF 680CfltpNo ratings yet

- The First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsFrom EverandThe First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (57)

- High Road Leadership: Bringing People Together in a World That DividesFrom EverandHigh Road Leadership: Bringing People Together in a World That DividesNo ratings yet

- Summary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendFrom EverandSummary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverFrom EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (186)

- How to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersFrom EverandHow to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (95)

- Spark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessFrom EverandSpark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- Think Like Amazon: 50 1/2 Ideas to Become a Digital LeaderFrom EverandThink Like Amazon: 50 1/2 Ideas to Become a Digital LeaderRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (62)

- How to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobFrom EverandHow to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (37)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeopleFrom EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeopleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2568)

- The Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthFrom EverandThe Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (35)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0From EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsFrom EverandBillion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (52)

- Good to Great by Jim Collins - Book Summary: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...And Others Don'tFrom EverandGood to Great by Jim Collins - Book Summary: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...And Others Don'tRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (64)

- 25 Ways to Win with People: How to Make Others Feel Like a Million BucksFrom Everand25 Ways to Win with People: How to Make Others Feel Like a Million BucksRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (37)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelFrom EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthFrom Everand7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (52)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: 30th Anniversary EditionFrom EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: 30th Anniversary EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (338)

- Get Scalable: The Operating System Your Business Needs To Run and Scale Without YouFrom EverandGet Scalable: The Operating System Your Business Needs To Run and Scale Without YouRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Management Mess to Leadership Success: 30 Challenges to Become the Leader You Would FollowFrom EverandManagement Mess to Leadership Success: 30 Challenges to Become the Leader You Would FollowRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (27)

- The Friction Project: How Smart Leaders Make the Right Things Easier and the Wrong Things HarderFrom EverandThe Friction Project: How Smart Leaders Make the Right Things Easier and the Wrong Things HarderNo ratings yet

- Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking TogetherFrom EverandSuperminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking TogetherRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- The Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceFrom EverandThe Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (22)

- Leadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsFrom EverandLeadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)