Professional Documents

Culture Documents

At First U Dont Succeed

Uploaded by

Mary StellOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

At First U Dont Succeed

Uploaded by

Mary StellCopyright:

Available Formats

Asia Pacic Business Review Vol. 15, No.

2, April 2009, 163180

If at rst you dont succeed: globalized production and organizational learning at the Hyundai Motor Company

Christopher Wrighta*, Chung-Sok Suhb and Christopher Leggettc

a Faculty of Economics and Business, The University of Sydney, Australia; bAustralian School of Business, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; cSchool of International Business, The University of South Australia Adelaide, Australia

This article reviews the development of a global production system through a crosscase analysis of the establishment of Hyundai Motor Companys ve major overseas production facilities. It concludes that establishtying a global production network can be a catalyst for organizational learning and the development of new competencies; in particular, that the complexities and uncertainties of operating in unfamiliar economic and cultural contexts provide a powerful impetus to increasing a rms absorptive capacity. The article identies the strategies that enabled the Hyundai Motor Company to learn from its initial failures in overseas production. It focuses on the localization of production, the internal transfer of experienced staff, the codication of previous experience and the use of aggressive goal-setting. The analysis suggests that organizational resilience, that is the ability to rebound from initial failure, is a further important aspect in the process of organizational learning. Keywords: globalized production; Korea; organizational learning; resilience

Introduction The history of the Korean automotive industry has been a rags to riches story. The Hyundai Motor Company (HMC) was established in 1967 to assemble American designed cars for local consumption. By 2005, it had become the sixth largest automobile producer in the world and a major competitor to more established producers that included GM, Ford and Toyota (Treece 2006). Considering that at HMCs inception Koreas major exports were simple, labour intensive products such as textiles, clothing and footwear, HMCs growth has been remarkable. No Korean companies had previous experience of automobile assembly and there were no supporting industries. Nevertheless, within 30 years HMC has become one of the worlds leading automobile manufacturers. Previous research has attributed HMCs rapid growth and competitiveness to government policy, a diligent workforce, executive leadership and organizational learning (KIET 1994, 1999, Hyun 1995, 1997, Lee 1995, Kim 1997, 1998). However, less attention has been paid to the relationship between the increasing globalization of HMCs operations over the last 20 years and its international competitiveness (for an exception see Kim and Lee 2001). This article examines HMCs establishment of a global production network since the late 1990s, and demonstrates how this contributed to the companys increasing competitiveness. It begins with an overview of HMCs globalization efforts and reviews plausible theoretical explanations of it. The case of HMC, we argue, departs from

*Corresponding author. Email: c.wright2@econ.usyd.edu.au

ISSN 1360-2381 print/ISSN 1743-792X online q 2009 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/13602380701698418 http://www.informaworld.com

164

C. Wright et al.

conventional stage theories of internationalization. We suggest a more viable theoretical explanation involves a knowledge-based view of the rm in which the globalization process, in creating new and complex challenges, is an essential contributor to organizational learning and capability building. In the main section of the article we provide a detailed cross-case comparison of the establishment and development of HMCs ve major overseas production centres. In particular, we focus on the way in which these attempts to establish offshore production contributed to HMCs core competencies in car manufacturing, supplier relations and marketing. In the concluding section, we review the cross-case analysis and analyse how HMCs attempts to establish viable global production facilities became a valuable learning experience for the company. In particular we stress how HMCs experience of globalized production highlights the importance of organizational resilience as part of the learning process. While existing theories of organizational learning stress a variety of ways in which knowledge is imported and diffused, less attention has been directed to the ability of an organization to endure initial failure, maintain its commitment to a path of action and learn from past mistakes in developing new capabilities. Literature review: growth through globalization The Korean government rst promoted the development of a local automobile industry in 1962, when it launched its rst Five-Year Economic Development Plan and passed the Automobile Industry Protection Law. The subsequent expansion of the industry can be divided into four periods: preparation for local production from 1962 to 1971; the development of local models from 1972 to 1982; mass production from 1983 to the mid-1990s; and most recently, global production from the late 1990s. HMC led the Korean automobile industry with its production of the Ford Cortina in 1968. As shown in Table 1, HMCs subsequent growth was largely due to exports, because of the then small size of the domestic market. The complete knock down (CKD) assembly of the Cortina was followed by the development of HMCs own model in 1972. The period of mass production and globalization that began in 1983 can be divided into the following stages: export through sales agents from 1983 to 1990; expansion through sales ofces from 1990 to 1994; the beginning of overseas production through knock down (KD) assembly from 1995 to 1998; and the beginning of the relocation of complete production systems overseas from 1999 (Hyun 1995, p. 6267, Kim and Lee 2001, Lansbury et al. 2006). Prima facie, HMCs progress towards globalization supports the stage theory of Johanson and Vahlne (1977, 1990), in which the rm begins with no export activities and then moves through a sequence of stages involving export via independent representatives, the establishment of overseas sales subsidiaries and, eventually, overseas production units. According to this theory, experience accumulated through a previous stage is essential for progress to the next stage. Firms enter new foreign markets where the perceived market uncertainty is low, progressively moving to markets with greater psychic distance, such as in language, culture and institutions. However, the progress of the Korean automobile companies differs from this model in two ways. First, the increase in exports took place simultaneously with the rapid expansion of domestic sales, when large-scale investments resulted in excess capacity. Second, Korean auto rms globalization strategies were not carried out according to cultural proximity or psychic distance. Instead, subsidiaries were established in various parts of the world simultaneously, with different modes of investment in each (Oh et al. 1998, Kim and Lee 2001). Even for market-seeking investment, market size has tended to dominate the choice of location (Suh and Seo 1998).

Asia Pacic Business Review

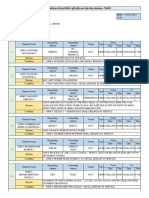

Table 1. Production, domestic sales and exports of HMC (1970 2002). Domestic sales Year 1970 1973 1975 1976 1979 1980 1982 1984 1985 1987 1988 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Production 4630 6989 7092 19,289 104,815 61,239 90,983 140,871 241,000 607,000 647,000 614,000 770,000 996,000 1,273,000 1,347,000 899,000 1,307,000 1,583,000 1,555,000 1,758,000 Units 4225 6966 7321 18,015 80,798 47,903 72,910 88,854 107,000 188,000 237,000 389,000 516,000 653,000 784,000 710,000 324,000 571,000 647,000 707,000 770,000 % 100 100 100 93.3 77.1 78.2 80.1 63.1 44.3 31.0 36.5 63.3 67.0 65.6 61.6 52.7 36.0 43.7 40.9 45.5 43.8 Units 0 0 0 1042 19,510 16,244 17,543 50,379 120,000 408,000 408,000 215,000 255,000 350,000 495,000 611,000 623,000 703,000 886,000 843,000 984,000 Exports

165

% 0 0 0 6.7 22.9 21.8 19.9 36.9 55.7 69.0 63.5 36.7 33.0 34.4 38.4 47.3 64.0 56.3 58.1 54.5 56.2

Source: HMC (2003a).

An examination of the globalization of HMC reveals three themes: 1) its growth depended on the expansion of international sales; 2) it began to globalize its production before it had developed signicant competitive advantage; and 3) it built its competitive advantage on its experiences in international markets. Traditional foreign direct investment (FDI) theories do not fully explain the internationalization of HMC because most regard the competitiveness of the rm as a precondition for internationalization. Theories of organizational learning While most traditional internationalization theories are silent on the process of the development of rm-specic competitive advantage, a dynamic capabilities perspective, which focuses on the way in which organizations learn new skills and competencies (Cohen and Levinthal 1990, Grant 1996, Teece 1998), offers insight into how global production stimulated HMCs competitiveness. A growing literature has stressed the centrality of organizational learning to a rms competitiveness. In particular, the ability of a rm to adapt and innovate its internal resources and capabilities is seen as central to competitive advantage (Nonaka 1994, Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). However, successful organizational learning is a complex process, with individual and political limits to deep or double-loop learning (Argyris 1977, Argyris and Schon 1996), and the stickiness of knowledge often limiting the transfer of best practice within and across a rms boundaries (Rogers 1995, Szulanski 1996). A key concept here is the rms absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal 1990), or its ability to recognize, internalize and apply new knowledge. In particular, a rms pre-existing level of knowledge provides a basis for recognizing the potential of new

166

C. Wright et al.

knowledge and future learning and innovation, in that, prior knowledge permits the assimilation and exploitation of new knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal 1990, p. 135 136). Hence, the ability of a rm to learn involves more than simple exposure to new sources of knowledge; it also hinges upon its ability to absorb new knowledge internally through its communication and transfer to sub-units and its integration with internal processes, or, as Cohen and Levinthal (1990, p. 131) put it, the intensity of effort of its application. Also stressed in the literature are the degree of cognitive distance between new knowledge and a rms existing knowledge base (Nooteboom 2004) and the importance of organizational support for social integration (Zahra and George 2002), such as a shared vision, and trust-based relations between individuals and sub-units (Inkpen and Tsang 2005). An example of the application of organizational learning in the Korean context is provided by Kim (1997, 1998). In his study of HMCs approach to early capability building to catch up with its global competitors, Kim demonstrates how HMC acquired migratory knowledge to increase its knowledge base, and then used internally-generated crises (typically ambitious short-term goals) to intensify its learning effort. Kim argues that such crisis construction was central to HMCs ability to shift from imitation to innovation. This insight into the functionality of organizational crises for stimulating absorptive capacity adds another contingent dimension to the process of organizational learning, one that is paralleled in the literature on organizational change (Kotter 1995). However, we believe another aspect of organizational learning highlighted by the example of large Korean companies, such as HMC, is the resilience of their learning effort. While writers such as Schein (2004) and Argyris (1977, Argyris and Schon 1996) have emphasized that deep learning is often difcult and cathartic given the need to question underlying assumptions and challenge conventional modes of thinking, we suggest that resilience in the face of initial failure is another important aspect of successful organizational learning. This involves not only a long-term commitment to the assimilation of new knowledge, but also an ability to commit to a strategy despite initial failure and, importantly, to rebound from these setbacks and use past mistakes as a source of learning and competency building. As Sitkin (1992) has argued, experiencing failure can result in a greater readiness to learn, particularly through reection on the causes of failure which can lead to more informed decisions in the future. As is the situation with individuals, we suggest that organizational resilience is a rare quality, particularly where the challenges are signicant and a plurality of stakeholders can undermine the organizations unity of purpose. Research questions and rationale In the following study we build on Kims earlier analysis of organizational learning at HMC (Kim 1997, 1998) and apply it to the more recent experience of the companys strategy of global production. In particular, we argue that the move from domestic to overseas production raises new challenges for rms, particularly in operating in unfamiliar and uncertain economic and cultural contexts. While Kims analysis of HMCs earlier catching-up phase of domestic car production suggests a relatively smooth process of growing absorptive capacity based on the rms high intensity of effort and incrementally expanding knowledge base, establishing overseas production facilities raises new and far more complex challenges. As we shall see, HMCs experience in establishing foreign production centres encountered many setbacks and early failures. Our research seeks to answer the following questions. First, how did HMCs prior experience help or hinder the

Asia Pacic Business Review

167

rms move into globalized production? Second, how did HMC overcome its early failure in establishing overseas production plants? Third, what types of supporting organizational practices were required to learn from its early setbacks? Fourth, in what ways might early failure be a necessary ingredient for future success in terms of organizational learning? Rather than a detailed analysis of the specic mechanisms of knowledge transfer between business units and functions, our focus in this article is to provide a broad overview of the way in which the company was able to rebound from its early failures in offshore production and learn from these setbacks. HMC has made large scale investments in ve countries to date with production plants established in Canada, Turkey, India, China and the USA. We review the establishment of each of these operations and focus on how each contributed to an eventually successful strategy of overseas production. Methodology In developing the cross-case analysis, we have used a combination of existing secondary literature, company documentation, interviews with senior HMC managers, and eld-trips to Korean and overseas production sites. During 2003 and 2004, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a cross-section of senior managers in HMCs Corporate Planning Division, focusing on the strategic planning, international business and human resource functions. We also interviewed HMC managers who had worked at the companys Indian and Chinese plants, and overseas production engineering and human resource managers who had been involved in the planning of the American plant in Alabama. We also conducted a series of interviews with a former HMC president and vice-chairman who had been involved at a senior level in many of the overseas production ventures, including oversight of the construction of the Chinese factory. These interviews provided us with qualitative data on HMCs globalization strategies and practices that supplemented ofcial reports and literature. In addition, two of us made eld-trips to the companys Indian and Korean production facilities to examine rst-hand the applications of production technology at different locations. On the basis of existing secondary literature, the interview data, ofcial documentation and eld notes, we wrote up case reports of each of HMCs overseas production ventures. We then sent these to key company informants for corroboration. The combined sources enabled a detailed understanding of the history and development of HMCs strategy for global production. While limitations of space prevent an extensive description of the nuances of knowledge ows within and across each plant, in the sections that follow we outline the key developments in HMCs attempt to successfully globalize its production system. Data analysis A failed experiment: HMCs Greeneld plant in Canada HMCs rst attempt at overseas production was in Canada, which had been a focus of exports since the early 1980s. Mounting pressure in North America to restrict automotive imports was a major factor in HMCs decision to establish a Canadian production plant (HMC 1992, p. 562 563). However, the hasty decision, made in July 1985 within a few months of the announcement of a tariff on Korean-made cars, overlooked the projects potential shortcomings. HMC invested CAN$382 million in the construction of the Canadian plant at Bromont in Quebec. It had selected Bromont because the Quebec provincial government had

168

C. Wright et al.

promised to provide substantial grants, including a 400-acre greeneld site, CAN$9 million in employee training, and an interest subsidy for investment amounting to approximately CAN$100 million over ve years. Production began in January 1989 with a capacity of 100,000 units per annum of the Sonata on a two shift basis (HMC 1992, p. 650 653), but HMC soon encountered major problems with the plants location. It took as long as 23 days to transport CKD parts from Ulsan in Korea to Bromont and local parts suppliers were located hundreds of miles from the plant. Consequently, HMC logistic costs were high approximately 5% of total material costs (HMC 1992, p. 651). In order to satisfy the minimum requirements of the Canadian Value Added (CVA) and the North American Value Added (NAVA) taxes, HMC had sought to increase parts localization for its Bromont plant. In 1989, 40 parts were supplied by 15 local manufacturers; by 1992, this had risen to 351 from 63 suppliers. The localized parts were mainly highly priced items and those that would have been vulnerable to damage if they had been transported from Korea. However, main components, such as engines and transmissions, were transported from Korea as CKD parts, leaving the localization level at Bromont still lower than the NAVA requirement of 50%, thus inducing HMC to invest in a press shop (interview with HMC General Manager, Planning Ofce, 27 August 2003). The Bromont plant was HMCs rst attempt at highly automated manufacturing: the automation of the body shop at Bromont was 85% compared with only 65% at the Ulsan 2 plant in Korea. Thus labour productivity at Bromont should have been 30 to 40% higher than in the Korean plants (Korea Economic Daily 1991). However, while the decision to invest in automated production was driven by higher Canadian wage rates, this represented a signicant departure from the HMCs previous experience which in combination with the management of a non-Korean workforce and related employee relations problems, adversely affected productivity and quality (Lansbury et al. 2006). HMCs production problems in Canada were compounded by its inadequate knowledge of the North American medium passenger car market. Except for enlarging its engine, HMC did not adapt the design of the Sonata for North American customers, thus placing it at a competitive disadvantage to Toyotas Camry and Hondas Accord. While HMC emphasized price competitiveness, Toyota and Honda satised the consumer preference for quality and reliability (HMC 1992, p. 718 720, interviews with HMC Director, Product Planning Division and HMC General Manager, Planning Ofce, 27 August 2003). In 1989, with sales of only 14,000 units but a capacity of 100,000 units, the Sonata failed to achieve its North American target. In 1990 91 production of the Sonata failed to exceed 30,000, and later dropped below 20,000. In an effort to sustain the Sonata, HMC negotiated with Chrysler to supply Bromont-produced Sonatas badged as Eagles. This was not a successful development and in 1993 the Bromont plant was shut down. HMCs rst attempt at overseas production had ended in failure (HMC 1992, p. 654 655). A further setback: the joint venture plant in Turkey In spite of its failure in Canada, in 1993 HMC established a joint venture (JV) plant in Turkey. Turkey was regarded as a promising market and HMC forecast that sales would exceed one million units by 2001 if Turkey joined the European Union (EU). A plant in Turkey could become a strategic base from which to make inroads into Asian markets. Turkey had maintained bilateral treaties with its neighbours in the Middle East and preferential tariffs applied to Turkish exports to these countries (HMC 1992, p. 774, Korea Economic Daily 1997).

Asia Pacic Business Review

169

Initially, HMC established the Hyundai Assan Otomotiv Sanyai ve Ticaret A.S. (HAOS), a 50 : 50 joint venture with the Kibar Business Group, to construct a local CKD assembly plant. However, the joint venture was postponed following Turkeys economic crisis of 1994. Eventually, in September 1995, HMC commenced construction of the CKD plant to assemble the Accent, a small passenger car, and the Grace, a minibus. The plant had a capacity of 60,000 units per annum (interview with HMC former CEO and ViceChairman, 22 August 2003). Wages were lower in Turkey than in Korea, and HMC introduced labour-intensive, hand-operated production technology and used less automated manufacturing processes than in its domestic plants. Consequently, the physical productivity of the Turkish plant was 25% lower than that of the Korean Ulsan factory (interview with HMC General Manager, Planning Ofce, 27 August 2003). Parts localization remained low in the Turkish facility, and HMC imported major components, such as engines and transmissions, as CKD units. Some Korean parts suppliers, such as Hanil Ehwa and Mando, established joint ventures with Turkish suppliers, and others signed technical agreements with local rms to supply the joint venture plant. Most of the local parts were bulky items, such as seats, door trims, carpets, and crush pads, or those requiring an intermediate level of technology, such as radiators, heaters and starter motors. Even so, only 34% of parts for the Accent and 20% of parts for the Grace were produced locally. In spite of HMCs aggressive marketing strategy and the inclusion of more optional accessories than Toyotas locally produced Corolla, initial sales were low less than 6,000 units in 1996, and only 29,000 units in 1997 (of which 22,789 were imported completely built units). In 1998, HAOSs total sales were 32,444 units (26,750 of which were locally assembled). There was a temporary recovery in 2000, but sales declined to less than 10,000 in 2001 and 2002, while exports were less than 1,000 units. For the second time, HMCs attempts to establish a viable overseas production facility had failed. The beginnings of success: Greeneld production in India In 1995, HMC undertook a third large-scale overseas investment and established a greeneld plant in India. India seemed a promising market following the economic reforms of the early 1990s, the resultant growing domestic demand, and a government friendly to foreign investment (Shah 1996, 2.01, Yoon 2002, p. 163 164). For HMC, a plant in India, halfway between Asia and Europe, would offer a strategic export base for its low-priced vehicles (Ha and Cha 2002, p. 133 135, Yoon 2002, p. 164). Although HMC had planned a small-scale, JV plant (20,000 to 30,000 units per annum), the difculties other foreign carmakers had experienced with Indian partners led it to opt for a 100%-owned subsidiary (Yoon 2002, p. 164 165). Hyundai Motor India (HMI) was established in May 1996 and invested US$457 million in the construction of a fully-integrated plant that included production facilities, engine and transmission shops, press, body, paint and assembly shops, and a plastic extrusion unit. Research and development (R&D) facilities were also constructed. The plant was designed to produce the Santro for the mini passenger car segment of the market and the Accent for the small passenger car segment, and had a production capacity of 120,000 units per annum. Learning from its experience in Canada and Turkey, HMC gave careful consideration to selecting the location for its Indian facility. After elaborate investigations regarding the distance to consumption markets, the location of local parts suppliers, the nature of the labour force, and utility conditions such as electric power and industrial water, it chose to locate the plant in the southern Indian city of Chennai. Even though the location involved

170

C. Wright et al.

high transport expenses because of the distance from consumption centres such as New Delhi, the company predicted this would be offset by the high level of parts localization and the availability of cheap marine or railroad transportation in place of expensive highway trucking. In addition, as no automobile manufacturers were located in the district, HMC anticipated the potential to acquire a higher market share than its competitors in the south of India (Yoon 2002, p. 165 166). HMC managers also gave careful consideration to the appropriate production strategy for the Chennai plant. Given lower wage costs they opted for a labour-intensive production technology, which meant that initially the automation rate and productivity of the Chennai plant were lower than the companys Korean factories (interview with HMC Deputy General Manager Human Resources, 5 July 2004, Yoon 2002, p. 168 169). Continuing to build on the lessons from the ventures in Canada and Turkey, over 70 expatriate HMC managers and engineers, many with over 15 years of production experience, were transferred to the Indian operation to oversee construction and production standards. Further, HMCs newly created Ofce of Overseas Production Technologies, based at its Korean Ulsan plant, played a key role in the formalization of the companys prior experience in establishing overseas production facilities. This ofce went on to become an important centre of expertise in the HMCs globalization programme, diffusing productivity and quality improvement programmes to overseas plants and training production engineers for overseas assignments. This allowed HMC to maintain control over production efciency in its overseas plants while planning the adjustment of car models and production systems to t local conditions (Lansbury et al. 2007, p. 96 98). Another dimension of the localized focus of HMCs Indian venture was the redesign of car models to t the local market better. Road testing and market surveys pointed to the need for HMI to design its cars for the Indian climate, road conditions, driving customs and local usage. To prevent overheating, HMC engineers boosted engine cooling and air conditioners, and, because of heavy rainfall and poor drainage greater water-resistance was included in the design. Other adjustments were made to the power train and horn and brake systems, ground clearance and suspension. To differentiate the Santro from local competitors, product designers emphasized up-to-date technology and created a sporty look (Ha and Cha 2002, p. 140 143, Yoon 2002, p. 167 169). In India, HMC was more proactive in its parts localization strategy than in Canada and Turkey. The Indian parts industry was underdeveloped and HMC adopted a singlesourcing strategy to realize economies of scale and encouraged over half of its preferred suppliers, who supplied 80% of parts, to relocate close to the Chennai plant. To insure the quality of its parts, HMC recommended that local suppliers had a technical agreement with foreign suppliers or receive advanced technology from the R&D division of HMC. In addition, HMC encouraged many of its Korean suppliers to establish local subsidiaries in India, especially those producing bulky parts or that required a high level of technology and quality. Together these measures resulted in parts localization of over 70% and the establishment of an extensive supply network (Yoon 2002, p. 172 173). HMC was highly successful in the Indian market. It started to sell the Santro in October 1998, and six months later had become the second largest manufacturer in India. Between 1999 and 2001, HMCs sales increased from 61,135 units to 82,837 and its market share rose from 12.7% to 16.2%. With the increase in sales, HMI increased production and enlarged its product line with the Accent in October 1999 and the Sonata in 2001. In 2000, it started to make a prot (6.2% net) and in 2002 remitted a US$25 million dividend to HMC headquarters (Korea Economic Daily 1999, Yoon 2002, p. 171). The Santro was named Car of the Year in 1999 by the Business Standard, an inuential Indian

Asia Pacic Business Review

171

newspaper, and both it and the Accent scored highly in quality surveys (Seoul Economic Daily 1999, Maeil Business Newspaper 2000). The success of the Chennai plant strengthened HMIs role as the regional headquarters for exports to developing countries, and was the beginning of HMCs global production network. In 2003, HMI planned to export 30,000 units to South West Asia and Europe. In addition, HMC strengthened the role of HMI as a supply base for core components and low value-added products within its global business structure (Maeil Business Newspaper 2003). Expansion in Asia: establishing a joint venture in China Following quickly on from its success in India, HMC focused on China as a potential production location. In 2001, the Chinese government relaxed the motor vehicle tax to promote domestic automobile demand, making China the largest emerging automobile market of the twenty-rst century. The Chinese governments Automobile Industry 10-5 Plan released in 2001 required Chinese manufacturers to develop an indigenous automobile industry in cooperation with leading automobile manufacturers. HMC saw the opportunity to make inroads into China, and in 2002 signed a memorandum of understanding on the establishment of Beijing-Hyundai Motor, a 50 : 50 JV with Beijing Automotive Holding Company (Lim 2003, p. 58 64). HMC took over the assets of the Beijing Automotive Holding Company, which was located close to the major market of Beijing and which could supply a low cost and abundant labour force (Motors Line 2003, p. 18). In the redesign and construction of its Beijing factory, HMC set an extremely tight deadline. Under the close supervision of senior HMC managers seconded to the project, construction work was conducted 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, resulting in the plant becoming operational in record time (interview with HMC former CEO and Vice-Chairman, 5 July 2004). As in India, the ready availability of low cost labour led HMC to rely on a labour-intensive production system to reduce total investment. This initial low level of automation reduced start-up costs, but could be quickly increased once production capacity increased (Motors Line 2003, p. 18 19). Once again, HMCs Ofce of Overseas Production Technologies played a central role in the diffusion of the companys prior learning in production control and efciency as well as in design localization for the new Chinese plant. Its experience in India led HMC to design its car for local conditions and consumer tastes, and adopt a strong parts localization strategy (Seoul Economic Daily 2003d, Motors Line 2003, p. 20). By 2003, over 64% of parts were supplied locally (Lim 2003, p. 71, Hyundai Motor Company News 2003). Such parts localization took advantage of differential government tariffs and further lowered manufacturing costs. The quality of local parts was maintained through evaluating the suppliers on the availability of permanent die moulds, the application of process controls, quality control and the effectiveness of their management. To penetrate the Chinese passenger car market, HMC expanded its dealer networks from Beijing to all other areas of the country, and, from its Korean experience, conducted dealer training in marketing, customer satisfaction and product knowledge. When it began sales of the Sonata in December 2002, HMC had only three dealers in Beijing city, but this had increased to 70 by December 2003, with a projected 180 dealers across China by the end of 2004 (Motors Line 2003, p. 21, Seoul Economic Daily 2003b, interview with HMC Executive Vice- President, Marketing Division, 21 August 2003).

172

C. Wright et al.

As with its Indian operation, HMCs Chinese joint venture proved highly successful. In its opening year in 2003, sales of the Sonata exceeded expectations, gaining 7% of market share and ranked fth among the medium and luxury passenger car segments (Seoul Economic Daily 8 April 2003a, Korea Economic Daily 2003b). The JV built a new engine plant producing 150,000 engines per annum and expanded the body, paint, and assembly shops to produce the Elantra for the upper small car segment. The production capacity of Beijing-Hyundai was projected to reach 200,000 units by 2005 (Seoul Economic Daily 2003c, Korea Economic Daily 2003b). Developing a high-tech Greeneld plant in the USA HMCs fth and most recent overseas production facility has been the establishment of a greeneld plant in the United States in 2002. The decision to locate inside the USA was to circumvent the anticipated difculties in trade relations resulting from HMCs increased exports to America. These had risen from 90,000 units in 1998 to 346,000 in 2001. Of automobile manufacturers with sales over 200,000 units per annum in the USA in 2001, only HMC was without a local production base in the North American Free Trade Area (HMC 2002, Maeil Business Newspaper 2002). In April 2002, HMC announced its decision to build the plant in Montgomery, Alabama with an investment of US$1.06 billion, and create a new subsidiary, Hyundai Motor Manufacturing America (HMMA). Construction of the plant commenced in April 2002 and commercial production began in May 2005 (Ward 2005). HMC chose Alabama because of the availability of relatively low-cost, non-union labour, easy accessibility, sound infrastructure, the proximity of a port in the South and US$254.8 million worth of incentives from the state of Alabama (HMC 2002, Chosun Ilbo 2002). The establishment of the US plant served to further develop HMCs internal capabilities by building on lessons from its operations in India and China. The Montgomery plant was fully integrated, with engine, press, body, paint, and assembly shops, and several testing facilities. Producing new versions of the Sonata and Santa Fe models, the plant had a production capacity of 235,000 units per annum assembled on a two shift basis, later expanding to 300,000 units per annum on a three shifts basis (HMC 2002, Hyundai Motor Company News 2002). While the Indian and Chinese plants had established HMCs ability to successfully operate labour-intensive overseas production facilities, the Alabama factory added another level of risk and complexity in that it was designed around the latest and most advanced production technology. For example, its exible production system included a body shop able to produce up to four models, and an assembly shop designed to assemble both monocoque and frame-type models on the same production line. Automation levels were also signicantly higher than any other existing HMC facility between 20 and 60% higher than its top production facility in Asan in Korea (interview with HMC former CEO and Vice-Chairman 22 August 2003, HMC 2002). Highlighting the ambitious goals of HMC managers for the Montgomery plant, HMC aimed to improve manufacturing quality to the level of the Lexus, perceived to be the highest quality car model in the world (HMC 2002, Korea Economic Daily 15 November 2003a). HMC drew on its expertise in automated production from within its Korean operations and, as had been the case in establishing its Indian and Chinese operations, used experienced expatriate managers to transfer knowledge to its American operations. It also established simulation assembly lines in its research and development centre in Korea to train American production workers (Chappell 2005).

Asia Pacic Business Review

173

As in India and China, HMC focused strongly on product localization, improving the adaptability of its new products to the American market. In order to compete with the Toyota Camry and Honda Accord, the most popular models in the USA, HMC developed successor models to the Sonata and the Santa Fe with improved interior design, new platforms and engines, and with transmissions with higher power and performance. Again drawing on its overseas experience, HMC adopted a sophisticated parts localization strategy for Alabama. HMMA expected to procure 320 items from local suppliers, amounting to 34% of the total procurement costs of the Montgomery plant. These parts were selected on the basis of quality and the requirement to satisfy American product liability regulations. HMMA also expected to procure 410 part items from Korean suppliers based in the USA (Courtenay 2005). The establishment of the highly-automated American plant highlighted HMCs broader strategic intention to improve its brand value as a producer of high quality cars (interview with HMC Manager, Marketing Division 21 August 2003, Korea Economic Daily 2002). Echoing the companys earlier pattern of aggressive goal-setting, such as the introduction in 1998 of an unprecedented 10 year/100,000 mile power-train warranty for cars sold in the USA (Krebs 1998), HMC pushed hard to raise its position in industry quality rankings. Quality surveys placed it at the top of volume brand cars and behind only elite brands, such as Porsche and Lexus (Rechtin 2006). Underpinning the improvement in quality was HMCs investment in its North American R&D, engineering and design facilities (Kim 1997, p. 119 124, HMC 2003b, p. 61). Consequently, HMCs North American investment has progressed a step further towards the establishment of an integrated global production network. This has extended beyond simple product ows between subsidiaries and headquarters, to the more valuable ow of advanced technological know-how and innovation. Discussion and implications of the research ndings Table 2 compares capacity, technology, product and parts localization, marketing and performance of HMCs ve major overseas subsidiaries. The ve subsidiaries exhibit signicant differences. All of them were established with a market seeking motive, but the plants in Turkey and India also had a trade seeking motive. Two of the plants were JVs and three wholly-owned subsidiaries. The rst two establishments, in Canada and Turkey, were unsuccessful, but those in India, China and the USA have been highly successful. While there is no discernible pattern of success due to the motivations for establishing an overseas production plant or to the ownership of the facility, the case studies indicate that HMC learned from its earlier failures and was able to apply the learning to its future sources of competitiveness within a relatively short time. From the closure of the Canadian plant, it took only ve years for the company to start production in India, and seven years from then until it began operating a world-class production facility in the United States. There were several reasons for HMCs transition from initial failure to ultimate success at global production. First, the initial failure provided learning opportunities that stimulated the development of new competencies in production, supplier relations and marketing. The ventures in Canada and Turkey, for example, were undertaken mainly because of a real fear of trade frictions and/or because of an expectation of growth in local demand. However, in both countries, HMC failed to anticipate changes in local market conditions and appeared unwilling to adapt its production to suit them. The Canadian plant was, at the time of its construction, technologically more advanced than HMCs Korean plants and was therefore a signicant advance on the companys previous experience. Combined with the management

174

Table 2. Cross-case comparison of HMCs ve major production plants. Canada Investment decision Production Motivation Capacity (units p.a.) Type of FDI Preparation Selection of location Scale Production process Product localization 1985 1989 1993 Market seeking (trade dispute) 100,000 Greeneld, wholly owned subsidiary Hurried decision, inadequate feasibility studies Driven by local government land & subsidies Press, body, paint & assembly production More advanced technology than within Korean HMC plants Low level of product localization, single model (Sonata) Turkey 1993 1996 present Market seeking & trade seeking (to EU) 60,000 Joint venture (Kibar Business Group) Cautious attitude due to the unstable economic climate Pre-determined India 1996 1998 present Market seeking & trade seeking (to neighbouring developing economies) 120,000 Greeneld, wholly owned subsidiary Careful planning Based on local parts suppliers, labour force & absence of labour unions Self-sufcient fullyedged plant Labour-intensive production technology. Use of former Canadian machinery Medium price & high quality focus. Product customization for Indian market China 2002 2003 present Market seeking Initially 50,000. Estimated increase to 1,000,000 by 2010 Joint venture (Beijing City) Aggressive planning and extremely fast construction Pre-determined but optimal location in terms of market, logistics & available labour Self-sufcient fullyedged plant Labour-intensive production technology Modication of specications given local conditions USA

C. Wright et al.

2002 2005 present Market seeking (global production) Estimated initial production 235,000, later to 300,000 Greeneld, wholly owned subsidiary Careful planning and feasibility study Based on low-cost, high quality labour force, logistics & infrastructure Self-sufcient fullyedged plant Latest and most advanced technology. Higher productivity than Korean facilities Localization of vehicle size, interior design. Strong emphasis on improved quality

Body, paint & assembly (mostly CKD) production Labour-intensive production technology Focus on small cars and minibus lines. No signicant modication

Parts localization

Main components imported from Korea

Low localization rate

Marketing strategy Performance

Market not favourable, focus on price competitiveness Failure (low quality, low technology). Low level of product design and precision. High supply costs and unreliable logistics

Aggressive marketing

Failure given decreasing sales over time. Domestic demand not favourable. Exports limited due to quality problems

Evaluation

FDI before substantial competitiveness was accumulated. Poor location decision. No formal strategy. Single model production increased risks of insufcient demand

Problems of quality control in joint venture relationship. Not an appropriate location as an export base. Uncertain demand

Facilitated joint ventures of subsidiaries of Korean & local suppliers. Emphasis on quality control Localized marketing strategies. Low price entry, later quality competition Highly successful. Increasing market share, and prots. Began exporting in 2000 to other developing countries. Becomes a supply base for core components and other parts Learning from previous failures. First successful case of HMCs global production. Beginning of global production

Strong emphasis on Korea subsidiaries & carefully selected local suppliers (64% localization rate in 2003) Nationwide marketing & aggressive advertising. Higher price & quality Highly successful. Surpassed the sales target in 2003. By 2004 exceeding the break even point

Very high ratio of local supply & Korean subsidiaries Aim to create the brand image of a tier one carmaker Yet to be evaluated, although constructed on time and a belief that it will achieved near best practice standards

Asia Pacic Business Review

Successful joint venture. Accumulated know-how in FDI

Global production. Most advanced technology used in overseas production. Global network of R&D & ow of know-how between head ofce and subsidiaries

175

176

C. Wright et al.

of a non-Korean workforce and poor labour relations (Lansbury et al. 2006), the Canadian experiment appears to have been beyond the companys existing capabilities (see also Kim and Lee 2001, p. 331). While the Turkish plant was a more labour-intensive operation, unfavourable market conditions and low technical competence hindered sales and exports, thereby also limiting the success of this venture. The turnaround in the performance of HMCs globalization began with the construction of the Indian facility. Here HMC drew on its experience in more routine labour-intensive mass production, and, importantly, augmented this by recognizing the need to tailor its offshore production facilities to t the local context, something learned from the Turkish and Canadian failures. HMC termed this recognition its glocalization strategy (interview with HMC Export Planning Team Manager 5 July 2004, HMC 2003b, p. 60). A review of HMCs localization and marketing strategies reveals that it adopted more locally appropriate strategies in India, China and the USA than in Canada and Turkey. In the Chennai, Beijing and Montgomery subsidiaries the localization of the product was in response to local demand. Parts localization levels were also higher in India, China and America than in Turkey or Canada and supplier networks incorporated both local and Korean subsidiaries. The success in India contributed signicantly to HMCs subsequent establishment of a global network, in which it not only exported CKDs to subsidiaries, but also increasingly imported from them as well, an indication of the successful transfer of technological knowhow from head ofce. Core parts produced in the subsidiary in a less developed country are now fully integrated into HMCs global production network (HMC 19982001). The case study data shows HMCs initial knowledge base to have been inadequate for the move into offshore production. Nevertheless, HMC rebounded from the early failures remarkably quickly, and learned from them, most notably around the need to invest much greater effort in localizing offshore production. In particular, HMC utilized a range of supporting organizational practices to harness the lessons from its initial setbacks in global production. For example, following the failure of the Canadian and Turkish operations, HMC developed comprehensive internal guidelines and strategies for establishing foreign facilities that contributed to the improved performance of its later establishments (HMC 2001, interviews with HMC former CEO and Vice-Chairman, 22 August 2003 and 5 July 2004). Hence one of the key ways HMC was able to learn from its previous mistakes was through the codication of experience through formal plans and guidelines for offshore production, resulting in explicit knowledge which could guide future action. Specialist internal groups, like the Ofce of Overseas Production Technologies, were also established with a specic focus on the diffusion of prior learning amongst the companys overseas subsidiaries. Added to this, HMC also focused on the internal transfer of staff experienced in the companys earlier overseas production efforts to its later offshore facilities. As we have noted, this was pronounced in the Indian and Chinese plants, where a signicant cadre of Korean HMC managers ensured the transmission of prior learning (interviews with HMC former CEO and Vice-Chairman, 22 August 2003 and 5 July 2004). Thus, rather than being dissipated, tacit internal knowledge was fed back into the planning process, ensuring mistakes were not repeated. Most recently, internal knowledge exchange has extended to the training of overseas employees within the companys Korean R&D facilities. HMC also continued its practice of internally-generated crises as a catalyst to the intensity of its learning efforts. In the overseas facilities, internal crises were generated by, among other things, aggressive construction deadlines, demanding production targets and quality benchmarks, and reinforced by an overarching goal to become a Top Five global carmaker by 2007 (HMC 2003b, p. 60). As Kim (1998) has observed, during HMCs catching up phase, internally generated crises increased the intensity of corporate

Asia Pacic Business Review

177

learning by focusing the attention of all organizational participants on a clearly articulated performance gap and increasing the intensity of effort to learn and close the gap. Internally generated crises have served to redirect HMC away from a reputation for low cost products towards high quality car production, the culmination of which has been the sophisticated subsidiary in America. The American case, with its investment in R&D and achievement of number one ranking for quality in volume car brands, suggests that HMC has indeed moved beyond imitative learning to innovative learning (Kim 1997, 1998). However, while our study supports Kims earlier analysis, we suggest the globalization of production at HMC also demonstrates the importance of organizational resilience as a key component of organizational learning. Rather than retreating from further efforts to globalize production following its initial failures in Canada and Turkey, HMC management pursued their goals with even greater tenacity. This was assisted by a strong organizational culture and shared values which complemented such a resilient attitude to learning from failure. In this respect, the HMC experience may be limited in its application, in that the strong, unitary culture of Korean corporations and their long-term strategic focus differs markedly from the more contested and short-term focus of western corporations (Laverty 1996). Indeed, as recent events suggest, changes in the rms external context are likely to require an ongoing ability to adapt to changed circumstance and learn from past experience (Jin 2007). Conclusion HMCs example suggests that establishing global production facilities provides a learning experience from which a rms competitive advantage can be strengthened. Organizational learning and change literature has identied conict and crisis as a means of challenging underlying assumptions and of learning new ways of thinking and doing (Argyris 1977, Kotter 1995). Establishing offshore production facilities and adapting to foreign and uncertain markets tests a rms existing resources and capabilities, reveals areas of hidden weakness and is a force for further organizational change and improvement. HMCs decision to globalize its production and then to become a world-class automobile manufacturer generated an internal crisis qualitatively similar to the companys earlier catching up phase of domestic production (Kim 1998). Harnessing such learning required practices which promoted the sharing of both explicit knowledge of globalization (such as formal policies and guidelines), as well as tacit knowledge (for example the transfer of experienced employees across global operations). HMCs establishment of a globalized production network also highlights the importance of organizational resilience as a key component of organizational learning. The ability to rebound from early setbacks and learn from mistakes appears to be a distinguishing characteristic of HMCs rapid modernization and innovation, and an aspect of their learning strategy which has been neglected. Further research is necessary to distinguish to what extent this quality is linked to Korean or Asian business culture or something that other companies in other industries and countries have developed to varying degrees. Moreover, the different ways in which resilience as a learning strategy is developed and how this is expressed at the micro level of intra-organizational relations requires further investigation. Overall though, our study highlights the benets to organizational learning that accrue from a long-term strategic focus and a culture of resilience in the face of initial failure. It is the knowledge that develops from reecting upon initial failure that can provide the expertise necessary for future success.

178

C. Wright et al.

Notes on contributors

Christopher Wright is Associate Professor in Organizational Studies at the University of Sydney. He has published extensively on the history and diffusion of management knowledge, managerial identity, and technological and workplace change. His current research interests include the role and impact of internal consultants, change agency discourse and management consulting careers. Chung-Sok Suh is Associate Professor in Organisation and Management at the University of New South Wales. The main areas of his research and publication are globalisation strategy of Asian multinational enterprises and theories of internationalisation and foreign direct investment. He can be contacted on c.suh@unsw.edu.au. Chris Leggett is the former Professor of Management in the School of Management at the University of South Australia. He has taught and researched Employment Relations in many countries, with special attention to East and Southeast Asia.

References

Argyris, C., 1977. Double loop learning in organizations. Harvard business review, 55 (5), 115125. Argyris, C. and Schon, D.A., 1996. Organizational learning II: theory, method and practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Chappell, L., 2005. Hyundais U.S. workers train for Santa Fe in Korea. Automotive news, 28 November, p. 16. Chosun Ilbo, 2002. The choice of Alabama in the US. 22 April, p. 19. Cohen, W.M. and Levinthal, D.A., 1990. Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative science quarterly, 35 (1), 128 152. Courtenay, V., 2005. Alabama starts Hyundai Mobis expansion. Wards auto world, 41 (6), 25. Grant, R.M., 1996. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the rm. Strategic management journal, 17 (Winter), 109 122. Ha, Y. and Cha, T., 2002. Hyundai jadongcha keurigo India (Hyundai Motor Company and India). Kyungyongkyoyukyeonku (Management education research), 5 (2), 130161. HMC (Hyundai motor company), 1992. Hyundai jadongchasa (The history of Hyundai Motor Company). Seoul: HMC. HMC, 1998 2001. Hyundai jadongcha Kyungyoungkwan (Collection of documents of HMC business strategies and practices). HMC internal sources. HMC, 2001. Kukjae kyungjaengryukyul hyanghan kil (On the road to global competitiveness). HMC internal sources. HMC, 2002. US kongjang geonseol bogo (Brief on US plant construction). HMC internal sources. HMC. 2003a. Jadongchasanup (The automobile industry). Seoul: HMC. HMC. 2003b. Everyday life enhanced by automobile technology. Seoul: HMC. Hyun, Y., 1995. The road to the self-reliance: new product development of Hyundai Motor Company, MIT IMVP (International Motor Vehicle Program). Working Paper, #w-0071a. Hyun, Y., 1997. New product development series Daewoo Motor: From joint venture to multiproject developer, MIT IMVP (International Motor Vehicle Program). Working Paper, #w-0159a. Hyundai Motor Company News, 2002. The production plant in the US. 22 April, pp. 2 3. Hyundai Motor Company News, 2003. The success of the China plant. 30 June, p. 4. Inkpen, A.C. and Tsang, E.W.K., 2005. Social capital, networks and knowledge transfer. Academy of management review, 30 (1), 146165. Jin, R., 2007. Hyundai motor cuts sales target in China. The Korea Times, 3 September. Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E., 1977. The internationalization process of the rm: a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of international business studies, 8 (1), 23 32. Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E., 1990. The mechanism of internationalism. International marketing review, 7 (4), 11 24. KIET (Korea Institute for Industrial Economics & Trade), 1994. Jadongchabupumkongupeui kisulkyeongjaengryeok kanfwhabangan (Technological competitiveness strengthening plan of automotive parts industry). Seoul: Korea Institute for Industrial Economics & Trade. KIET, 1999. Bupumsanup baljunjulyak (Development strategy of parts industry). Seoul: Korea Institute for Industrial Economics & Trade.

Asia Pacic Business Review

179

Kim, L., 1997. Imitation to Innovation: The Dynamics of Koreas Technological Learning. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Kim, L., 1998. Crisis construction and organizational learning: dynamics of capability building in catching-up at Hyundai Motor. Organization science, 9 (4), 506 521. Kim, B. and Lee, Y., 2001. Global capacity expansion strategies: lessons learned from two Korean carmakers. Long range planning, 34 (3), 309 333. Korea Economic Daily, 1991. Hyundai Motor Company in Canada. 5 May, p. 1. Korea Economic Daily, 1997. The Turkey plant of HMC starts production. 22 September, p. 1. Korea Economic Daily, 1999. Used car store of HMC in Changwon. 27 July, p. 13. Korea Economic Daily, 2002. Increase in domestic sales and sluggish export. 2 April, p. 2. Korea Economic Daily, 2003. Hyundai Group joins KCC. 15 November, p. 1. Korea Economic Daily, 2003. Sales gures improve in Hyunder Motor China: prot expected within one year of operation. 17 November, p. 13. Kotter, J., 1995. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard business review, 73 (2), 59 67. Krebs, M., 1998. To counter stigma Hyundai bolsters warranty. New York Times, 8 November, p. 1. Lansbury, R.D., Kwon, S.-H., and Suh, C.-S., 2006. Globalization and employment relations in the Korean auto industry: the case of the Hyundai Motor Company in Korea, Canada and India. Asia Pacic business review, 12 (2), 131 147. Lansbury, R.D., Suh, C.-S., and Kwon, S.-H., 2007. The global Korean Motor Industry: the Hyundai Motor Companys Global Strategy. London: Routledge. Laverty, K.J., 1996. Economic short-termism: the debate, the unresolved issues, and the implications for management practice and research. The academy of management review, 21 (3), 825 860. Lee, C., 1995. Yurob jadongchasanupeui igusibnyeondae kyeongjaengryeok hoibokeui woncheon (The source of competitiveness recovery of the European automobile industry in the 1990s), Jadongchasanupdonghyang (Current trend of automobile industry). Hyundai Automotive Industry Research Institute. Lim, K., 2003. Joongkuk jadongcha sanuoeui hyunhwangkwa mirae (The present and future of the Chinese automobile industry). Seoul: Huashutang. Maeil Business Newspaper, 2000. Hyundai-Kia cars, entry in the Chinese market. 24 November, p. 14. Maeil Business Newspaper, 2002. Announcement of the production site at Hyundai Motors in the US. 2 April, p. 11. Maeil Business Newspaper, 2003. Hyundai Motor Company purchases the shares of Hyundai Mobis. 17 March, p. 23. Motors Line, 2003. Expansion in sales in HMI. January, pp. 10 13. Nonaka, I., 1994. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization science, 5 (1), 14 37. Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H., 1995. The knowledge-creating company: how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press. Nooteboom, B., 2004. Inter-rm collaboration, learning and networks an integrated approach. London: Routledge. Oh, D., Choi, C.J., and Choi, E., 1998. The globalization strategy of Daewoo Motor Company. Asia Pacic journal of management, 15 (2), 185 203. Rechtin, M., 2006. Survey: Hyundais the real deal. Automotive News, 12 June, p. 53. Rogers, E.M., 1995. Diffusion of innovations, 4th ed. New York: Free Press. Schein, E.H., 2004. Organizational culture and leadership. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Seoul Economic Daily, 1999. Hyundai Motor Company sales reaches 970,000 units. 4 January, p. 9. Seoul Economic Daily, 2003a Celebration of 10 million cars by Hyundai Motor Company. 8 April, p. 12. Seoul Economic Daily, 2003b. Strikes become mild in Hyundai Motors. 1 July, p. 39. Seoul Economic Daily, 2003c. Hyundai-Kia cars equipped with GPS system. 28 August, p. 9. Seoul Economic Daily, 2003d. Creating the image of the best car. 19 November, p. 9. Shah, S., 1996. Shaping the Indian automobile industry. Mumbai: Association of Indian Automobile Manufacturers.

180

C. Wright et al.

Sitkin, S.B., 1992. Learning through failure: the strategy of small losses. Research in organizational behavior, 14, 231 266. Suh, C.-S. and Seo, J.-S., 1998. Trends in foreign direct investment: the case of the Asia-pacic region. In: A. Levy, ed. Handbook on the globalization of the world economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 123 146. Szulanski, G., 1996. Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the transfer of best practice within the rm. Strategic management journal, 17 (Winter), 55 79. Teece, D.J., 1998. Capturing value from knowledge assets: the new economy, markets for knowhow, and intangible assets. California management review, 40 (3), 55 79. Treece, J., 2006. Asia-based automakers are racing toward global domination. Automotive News Europe, 12 June, p. 4. Ward, A., 2005. Hyundai moves into deep south. Financial Times, 23 May, p. 23. Yoon, D., 2002. Hyundai jadongchaeui indo jinchuljeonryakkwa aerosahang keukbokkwajeong (The strategy of making inroads into India and the processes of overcoming bottlenecks of Hyundai Motor Company). Kyungyongkyoyukyeonku (Management education research), 5 (2), 162 189. Zahra, S.A. and George, G., 2002. Absorptive capacity: a review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of management review, 27 (2), 185 203.

Interviews

HMC Deputy General Manager Human Resources. 5 July 2004. HMC Director, Product Planning Division. 27 August 2003. HMC Executive Vice-President, Marketing Division. 21 August 2003. HMC Export Planning Team Manager. 5 July 2004. HMC former CEO and Vice-Chairman. 22 August 2003. HMC former CEO and Vice-Chairman. 5 July 2004. HMC General Manager, Planning Ofce. 27 August 2003. HMC Manager, Marketing Division. 21 August 2003.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- APPLMC001 - ATX Catalog EnglishDocument519 pagesAPPLMC001 - ATX Catalog EnglishJuanje Tres CantosNo ratings yet

- Taniya Rawat: ObjectiveDocument1 pageTaniya Rawat: Objectiveanuj sharmaNo ratings yet

- IgniteDocument2 pagesIgniteMartinito MacraméNo ratings yet

- AWS - Lambda QuizletDocument20 pagesAWS - Lambda QuizletchandraNo ratings yet

- Workflow API Reference Guide PDFDocument340 pagesWorkflow API Reference Guide PDFRaghugovindNo ratings yet

- MOTHERBOARDDocument9 pagesMOTHERBOARDMUQADDAS ABBASNo ratings yet

- Big Data Analytics in Supply Chain Management Between 2010 and 2016Document12 pagesBig Data Analytics in Supply Chain Management Between 2010 and 2016Kuldeep LambaNo ratings yet

- FRIT 7739 - Technology Program Administrator - WeeksDocument6 pagesFRIT 7739 - Technology Program Administrator - WeeksdianambertNo ratings yet

- Steam Turbines: ASME PTC 6-2004Document6 pagesSteam Turbines: ASME PTC 6-2004Dena Adi KurniaNo ratings yet

- Circuit 1B: Potentiometer: Parts NeededDocument6 pagesCircuit 1B: Potentiometer: Parts NeededDarwin VargasNo ratings yet

- LAB3.2 - Connecting Windows Host Over iSCSI With MPIODocument13 pagesLAB3.2 - Connecting Windows Host Over iSCSI With MPIOwendy yohanesNo ratings yet

- Endress-Hauser Cerabar PMP11 ENDocument4 pagesEndress-Hauser Cerabar PMP11 ENSensortecsa SensortecsaNo ratings yet

- Element - 111 - 579-Bill of Quantity For Constructing Main House of MosqueDocument8 pagesElement - 111 - 579-Bill of Quantity For Constructing Main House of MosqueKapros Junior AphrodiceNo ratings yet

- V Ug Type ListDocument3 pagesV Ug Type ListDanang BiantaraNo ratings yet

- HILTI Catalogue 2012Document314 pagesHILTI Catalogue 2012Marius RizeaNo ratings yet

- Braking Unit Braking Resistor Unit CDBR Lkeb Instructions (Toe-C726-2g)Document54 pagesBraking Unit Braking Resistor Unit CDBR Lkeb Instructions (Toe-C726-2g)Pan TsapNo ratings yet

- Cat 2 STSDocument424 pagesCat 2 STSVardhanNo ratings yet

- 5.1 Software Test AutomationDocument20 pages5.1 Software Test Automationudhayan udhaiNo ratings yet

- ITIL TestsDocument54 pagesITIL TestssokzgrejfrutaNo ratings yet

- Interactive Schematic: This Document Is Best Viewed at A Screen Resolution of 1024 X 768Document17 pagesInteractive Schematic: This Document Is Best Viewed at A Screen Resolution of 1024 X 768vvvNo ratings yet

- Er Shutdown For 15.12.21 Rev1Document8 pagesEr Shutdown For 15.12.21 Rev1Gitesh PatelNo ratings yet

- DROPS - Reliable Securing Rev 04Document67 pagesDROPS - Reliable Securing Rev 04Chris EasterNo ratings yet

- JTM-30C Configuration & User Manual Rev-I PDFDocument12 pagesJTM-30C Configuration & User Manual Rev-I PDFVladimirs ArzeninovsNo ratings yet

- Intel Nehalem Core ArchitectureDocument123 pagesIntel Nehalem Core ArchitecturecomplexsplitNo ratings yet

- GPON OLT (P1201 08 1.0) User Manual Quick Configuration GuideDocument34 pagesGPON OLT (P1201 08 1.0) User Manual Quick Configuration GuideFedePonceDaminatoNo ratings yet

- ME 475 Mechatronics: Semester: July 2015Document22 pagesME 475 Mechatronics: Semester: July 2015ফারহান আহমেদ আবীরNo ratings yet

- Lecture01 IntroDocument20 pagesLecture01 IntroRijy LoranceNo ratings yet

- Yahaya Current CVDocument2 pagesYahaya Current CVJennifer PetersNo ratings yet

- Drive ActiveHybrid - V.4 GA8P70HZDocument15 pagesDrive ActiveHybrid - V.4 GA8P70HZTimur GorgievNo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter ICT ReviewerDocument5 pages1st Quarter ICT ReviewerazrielgenecruzNo ratings yet