Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Electoral College Reading and Handout

Uploaded by

csj6363Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Electoral College Reading and Handout

Uploaded by

csj6363Copyright:

Available Formats

The Electoral College decides who will be the next President Unlike other public office holders, the

President of the United States is not officially elected by popular vote. When people in a state vote, they seem to be voting to elect the president. They are really voting to choose electors. Electors are people who say that they will vote for a certain candidate. For example, in the upcoming election, some electors will pledge to vote for Bill Clinton; some electors will pledge to vote for Bob Dole. When the people of a state vote, the vote is counted for each candidate. When the final count is in, the electors who pledged to vote for the candidate with the most votes are all sent to the electoral college. That means that when the count is finished, the candidate who received the most votes in a state gets ALL of the electoral votes for that state. The candidate who receives the most votes in the electoral college wins. This may mean that a candidate can receive a minority of the popular vote but still win the election because he or she receives the majority of the electoral vote. By law the electors of each state cast their votes on a certain day in December. This vote usually takes place in each state capitol. They vote for President and for Vice President. Their election ballots are sent to the Senate. In January in a joint meeting of the House of Representatives and the Senate, the ballots are opened by the President of the Senate. One member of each major party counts the vote in the presence of all the Senators and Representatives. The candidate with the majority of electoral votes now officially wins the election. One interesting fact about the electoral college is that states have different numbers of electors. States have the same number of electors as they have Senators and Representatives. This means that states with larger populations have more electors and more votes in the electoral college.

The Electoral College in the Constitution Where Did the Electoral College Start? The electoral college was created by delegates to the Constitutional Convention. During the debates that took place during the convention, one group wanted Congress to elect the President, much as the current British system does. Another group didn't want Congress to have so much power, but they also did not want a popular vote to decide such an important election. As a result, they developed the electoral college, which is sometimes called an "indirect popular vote." The electoral college is defined in Article II, Section 1, Paragraphs 2-3 of the Constitution. It is amended in Amendment 12. How did the terms "Elector" and "Electoral College" come into usage? The term "electoral college" does not appear in the Constitution. Article II of the Constitution and the 12th Amendment refer to "electors," but not to the "electoral college." In the Federalist Papers (No. 68), Alexander Hamilton refers to the process of selecting the Executive, and refers to "the people of each State (who) shall choose a number of persons as electors," but he does not use the term "electoral college."

The founders appropriated the concept of electors from the Holy Roman Empire (962 - 1806). An elector was one of a number of princes of the various German states within the Holy Roman Empire who had a right to participate in the election of the German king (who generally was crowned as emperor). The term "college" (from the Latin collegium), refers to a body of persons that act as a unit, as in the college of cardinals who advise the Pope and vote in papal elections. In the early 1800's, the term "electoral college" came into general usage as the unofficial designation for the group of citizens selected to cast votes for President and Vice President. It was first written into Federal law in 1845, and today the term appears in 3 U.S.C. section 4, in the section heading and in the text as "college of electors." Is my vote for President and Vice President meaningful in the Electoral College system? Yes, within your State your vote has a great deal of significance. Under the Electoral College system, we do not elect the President and Vice President through a direct nation-wide vote. The Presidential election is decided by the combined results of 51 State elections (in this context, the term "State" includes DC). It is possible that an elector could ignore the results of the popular vote, but that occurs very rarely. Your vote helps decide which candidate receives your State's electoral votes. The founders of the nation devised the Electoral College system as part of their plan to share power between the States and the national government. Under the Federal system adopted in the U.S. Constitution, the nation-wide popular vote has no legal significance. As a result, it is possible that the electoral votes awarded on the basis of State elections could produce a different result than the nation-wide popular vote. Nevertheless, the individual citizen's vote is important to the outcome of each State election. What happens if no presidential candidate gets 270 electoral votes? If no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes, the House of Representatives elects the President from the 3 Presidential candidates who received the most electoral votes. Each State delegation has one vote. The Senate would elect the Vice President from the 2 Vice Presidential candidates with the most electoral votes. Each Senator would cast one vote for Vice President. If the House of Representatives fails to elect a President by Inauguration Day, the Vice-President Elect serves as acting President until the deadlock is resolved in the House. How is it possible for the electoral vote to produce a different result than the nation-wide popular vote? It is important to remember that the President is not chosen by a nation-wide popular vote. The electoral vote totals determine the winner, not the statistical plurality or majority a candidate may have in the nation-wide vote totals. Electoral votes are awarded on the basis of the popular vote in each State. Note that 48 out of the 50 States award electoral votes on a winner-takes-all basis (as does DC). For example, all 55 of California's electoral votes go to the winner of that State election, even if the margin of victory is only 50.1 percent to 49.9 percent. In a multi-candidate race where candidates have strong regional appeal, as in 1824, it is quite possible that a candidate who collects the most votes on a nation-wide basis will not win the electoral vote. In a two-candidate race, that is less likely to occur. But it did occur in the Hayes/Tilden election of 1876 and the Harrison/Cleveland election of 1888 due to the statistical disparity between vote totals in individual State elections and the national vote totals. This also occurred in the 2000 presidential election, where George W. Bush received fewer popular votes than Albert Gore Jr., but received a majority of electoral votes. What would happen if two candidates tied in a State's popular vote, or there was a dispute as to the winner? A tie is a statistically remote possibility even in smaller States. But if a State's popular vote were to come out as a tie between candidates, State law would govern as to what procedure would be followed in breaking the tie. A tie would not be known of until late November or early December, after a recount and after the Secretary of State had certified the election results. Federal law would allow a State to hold a run-off election.

A very close finish could also result in a run-off election or legal action to decide the winner. Under Federal law (3 U.S.C. section 5), State law governs on this issue, and would be conclusive in determining the selection of Electors. The law provides that if States have laws to determine controversies or contests as to the selection of Electors, those determinations must be completed six days prior to the day the Electors meet. What are the qualifications to be an elector? The U.S. Constitution contains very few provisions relating to the qualifications of electors. Article II, section 1, clause 2 provides that no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector. As a historical matter, the 14th Amendment provides that State officials who have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the United States or given aid and comfort to its enemies are disqualified from serving as electors. This prohibition relates to the post-Civil War era. A State's certification of electors on its Certificates of Ascertainment is generally sufficient to establish the qualifications of electors.

Must electors vote for the candidate who won their State's popular vote? There is no Constitutional provision or Federal law that requires electors to vote according to the results of the popular vote in their States. Some States, however, require electors to cast their votes according to the popular vote. These pledges fall into two categories -- electors bound by State law and those bound by pledges to political parties. The Supreme Court has held that the Constitution does not require that electors be completely free to act as they choose and therefore, political parties may extract pledges from electors to vote for the parties' nominees. Some State laws provide that so-called "faithless electors" may be subject to fines or may be disqualified for casting an invalid vote and be replaced by a substitute elector. The Supreme Court has not specifically ruled on the question of whether pledges and penalties for failure to vote as pledged may be enforced under the Constitution. No elector has ever been prosecuted for failing to vote as pledged. Today, it is rare for electors to disregard the popular vote by casting their electoral vote for someone other than their party's candidate. Electors generally hold a leadership position in their party or were chosen to recognize years of loyal service to the party. Throughout our history as a nation, more than 99 percent of electors have voted as pledged. How many times has the Vice President been chosen by the U.S. Senate? Once. In the Presidential election of 1836, the election for Vice President was decided in the Senate. Martin Van Buren's running mate, Richard M. Johnson, fell one vote short of a majority in the Electoral College. Vice Presidential candidates Francis Granger and Johnson had a "run-off" in the Senate under the 12th Amendment, where Johnson was elected 33 votes to 17.

Name: _______________________________ Period: _________ Define Electors: Popular Vote:

When the count is finished, the candidate who received the ________ votes in a state gets _______ of the electoral votes for that state. Explain this in your own words: The candidate who receives the most votes in the electoral college wins. This may mean that a candidate can receive a minority of the popular vote but still win the election because he or she receives the majority of the electoral vote.

When does the Electoral College vote? ________________When are the votes opened and counted? ________________ How is the number of electors decided upon for each state?

The Electoral College can also be called an _____________________________. Explain what that means.

Historically, where did the term electors and Electoral College come from?

Explain why your vote is important when electing the president. What influence does one vote have?

If no candidate receives a majority vote (from the Electoral College), who then votes for the president?

How is it possible for a Presidential candidate to win the popular vote but lose the election?

If two candidates were to tie in a state vote, what would happen?

What act disqualifies a person from becoming an elector?

Legally do electors have to vote along the states popular vote outcome? Explain.

You might also like

- OVF-CPC ElectCollege PDFDocument2 pagesOVF-CPC ElectCollege PDFJust ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Electoral College SystemDocument2 pagesElectoral College SystemSteve ExcellNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4: The Political System of The United States of AmericaDocument4 pagesLecture 4: The Political System of The United States of AmericaMillie JaneNo ratings yet

- American Gov Hon Research PaperDocument14 pagesAmerican Gov Hon Research Paperapi-596908445No ratings yet

- Us Presidental Election ProcessDocument7 pagesUs Presidental Election ProcessMuzaffar Abbas SipraNo ratings yet

- Andrew Koorndyk Final EssayDocument12 pagesAndrew Koorndyk Final Essayapi-534380859No ratings yet

- US President and PowersDocument8 pagesUS President and PowersSanya SinghNo ratings yet

- Popular V President - ReadingDocument3 pagesPopular V President - ReadingmishineNo ratings yet

- Presidential Elections and Other Cool FactsFrom EverandPresidential Elections and Other Cool FactsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Legal Brief: The Electoral CollegeDocument11 pagesLegal Brief: The Electoral CollegeIndependent Women's ForumNo ratings yet

- USA Elections in BriefDocument92 pagesUSA Elections in BriefBureau of International Information Programs (IIP)No ratings yet

- Commuting The Process of Travelling Between A Place of Residence and A Place of Work So Heres Some Alternative Suggestions To Go Around TrafficDocument7 pagesCommuting The Process of Travelling Between A Place of Residence and A Place of Work So Heres Some Alternative Suggestions To Go Around Trafficapi-346089328No ratings yet

- Electoral College: A Vestige of FederalismDocument67 pagesElectoral College: A Vestige of FederalismMarlie Ann NavaeraNo ratings yet

- Origins of The Electoral College: 45 Comments U.S. Historyphilosophy and Methodologypolitical Theory Randall G. HolcombeDocument9 pagesOrigins of The Electoral College: 45 Comments U.S. Historyphilosophy and Methodologypolitical Theory Randall G. Holcombedbush1034No ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know about The US Voting System - Government Books for Kids | Children's Government BooksFrom EverandEverything You Need to Know about The US Voting System - Government Books for Kids | Children's Government BooksNo ratings yet

- The Political System in The US: Historical DocumentsDocument3 pagesThe Political System in The US: Historical DocumentsRiaz khanNo ratings yet

- Electoral College FAQDocument3 pagesElectoral College FAQDavid SobandeNo ratings yet

- Electoral College EssayDocument9 pagesElectoral College EssayAnna-Elisabeth BaumannNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Electoral CollegeDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Electoral Collegefvgj0kvd100% (1)

- The Constitution of the United States: Updated for Better Government in the Twenty-First Century Second EditionFrom EverandThe Constitution of the United States: Updated for Better Government in the Twenty-First Century Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Jesus Torres - Electoral College Pro ConDocument12 pagesJesus Torres - Electoral College Pro Conapi-548156495No ratings yet

- Political System USADocument16 pagesPolitical System USAHannaNo ratings yet

- Electoral College PaperDocument5 pagesElectoral College PaperSergey MatevosyanNo ratings yet

- The Electoral College Should Be AbolishedDocument11 pagesThe Electoral College Should Be AbolishedZehraNo ratings yet

- MA - Fedral Urdu University Paper - III (Solved) - 10 YearsDocument40 pagesMA - Fedral Urdu University Paper - III (Solved) - 10 YearsShajaan EffendiNo ratings yet

- Quetzalli Morales - Electoral College Pro ConDocument12 pagesQuetzalli Morales - Electoral College Pro Conapi-547472366No ratings yet

- 20201117-PRESS RELEASE MR G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. ISSUE - The Australian & USA Misconceptions About ElectionsDocument4 pages20201117-PRESS RELEASE MR G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. ISSUE - The Australian & USA Misconceptions About ElectionsGerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- Electoral College Assignment (AP)Document6 pagesElectoral College Assignment (AP)Philip ArgauerNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument9 pagesResearch Paperapi-319970881No ratings yet

- The Myth of A Wasted VoteDocument8 pagesThe Myth of A Wasted Voteapi-250264035No ratings yet

- The Electoral College: How It WorksDocument15 pagesThe Electoral College: How It Workspolitix100% (7)

- DBQDocument2 pagesDBQapi-268989941100% (1)

- Adarsh Comp ConsDocument7 pagesAdarsh Comp ConsAmanNo ratings yet

- The Pro of Elections in The USADocument1 pageThe Pro of Elections in The USAAnna MokeevaNo ratings yet

- Hern - Final Research EssayDocument6 pagesHern - Final Research Essayapi-549205458No ratings yet

- The Electoral Votes of 1876 Who Should Count Them, What Should Be Counted, and the Remedy for a Wrong CountFrom EverandThe Electoral Votes of 1876 Who Should Count Them, What Should Be Counted, and the Remedy for a Wrong CountNo ratings yet

- Analisis Video Amerika Adelya Nur IndahsariDocument4 pagesAnalisis Video Amerika Adelya Nur IndahsariAdelya NurindahsariNo ratings yet

- Electoral College EssayDocument4 pagesElectoral College EssaytwigspanNo ratings yet

- Electoral College Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesElectoral College Thesis Statementxdqflrobf100% (2)

- Electoral College EssayDocument13 pagesElectoral College Essayapi-451587333No ratings yet

- Overview How The Us Elects Presidents 21065 FalseDocument5 pagesOverview How The Us Elects Presidents 21065 Falseapi-334706432No ratings yet

- Argument Essay FinalDocument4 pagesArgument Essay Finalapi-549247604No ratings yet

- Seniorinq ResearchpaperelectoralcollegeDocument7 pagesSeniorinq Researchpaperelectoralcollegeapi-320214636No ratings yet

- Government for Kids - Citizenship to Governance | State And Federal Public Administration | 3rd Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandGovernment for Kids - Citizenship to Governance | State And Federal Public Administration | 3rd Grade Social StudiesNo ratings yet

- Argument EssayDocument4 pagesArgument Essayapi-575350153No ratings yet

- Why Does The United States Use The Electoral CollegeDocument10 pagesWhy Does The United States Use The Electoral Collegeapi-583109211No ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Electoral SystemDocument12 pagesChapter 6 Electoral SystemДина ЖаксыбаеваNo ratings yet

- The Electoral College Pros and ConsDocument5 pagesThe Electoral College Pros and ConsShiino FillionNo ratings yet

- CongressDocument16 pagesCongressapi-164891616No ratings yet

- How the US Electoral College and presidential nomination process worksDocument2 pagesHow the US Electoral College and presidential nomination process workslifer elixeerNo ratings yet

- Elections Reading CompDocument2 pagesElections Reading CompReva LarsonNo ratings yet

- The Federal Election Commission, Cato Policy AnalysisDocument11 pagesThe Federal Election Commission, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Classroom Handouts Electoral College LessonDocument12 pagesClassroom Handouts Electoral College LessonPamela SmithNo ratings yet

- Constitution Study Guide Answers 2012-13-201209281055192860Document6 pagesConstitution Study Guide Answers 2012-13-201209281055192860Omama Akhtar QadriNo ratings yet

- Constitution Day 2020 SpecialDocument6 pagesConstitution Day 2020 SpecialChrisWhittleNo ratings yet

- Fact Report Regarding 2020 Selections (TNALC)Document4 pagesFact Report Regarding 2020 Selections (TNALC)jb_uspuNo ratings yet

- Checks and Balances Internet AssignmentDocument1 pageChecks and Balances Internet Assignmentcsj6363No ratings yet

- Executive Branch: Constitution Worksheet: Answers: 1Document2 pagesExecutive Branch: Constitution Worksheet: Answers: 1csj6363No ratings yet

- Unit One Test Review Spring 2012Document3 pagesUnit One Test Review Spring 2012csj6363No ratings yet

- Amending The ConstitutionDocument2 pagesAmending The Constitutioncsj6363No ratings yet

- Civic Participation ArticleDocument3 pagesCivic Participation Articlecsj6363No ratings yet

- Congress Compare and Contrast ChartDocument1 pageCongress Compare and Contrast Chartcsj6363No ratings yet

- Obama's Deal QuestionsDocument2 pagesObama's Deal Questionscsj6363No ratings yet

- 2.4 and 2.5 Overview Wksht.Document2 pages2.4 and 2.5 Overview Wksht.csj6363No ratings yet

- Origins Pol. Cartoon AssignmentDocument1 pageOrigins Pol. Cartoon Assignmentcsj6363No ratings yet

- The Legislative Branch and Constitution WKSTDocument1 pageThe Legislative Branch and Constitution WKSTcsj6363No ratings yet

- Bill Into LawDocument17 pagesBill Into Lawcsj6363No ratings yet

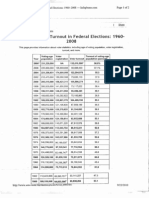

- Voter Turnout Chart and QuestionsDocument2 pagesVoter Turnout Chart and Questionscsj6363No ratings yet

- U.S. Government Final ReviewDocument2 pagesU.S. Government Final Reviewcsj6363No ratings yet

- Bill Into Law Graphic OrganizerDocument1 pageBill Into Law Graphic Organizercsj6363No ratings yet

- Presidential Truths ActivityDocument3 pagesPresidential Truths Activitycsj6363No ratings yet

- War Powers Resolution Debate Wksht.Document2 pagesWar Powers Resolution Debate Wksht.csj6363No ratings yet

- Election ProjectDocument2 pagesElection Projectcsj6363No ratings yet

- Voter Behavior ArticleDocument2 pagesVoter Behavior Articlecsj6363No ratings yet

- Increasing Taxes To Address The NationDocument1 pageIncreasing Taxes To Address The Nationcsj6363No ratings yet

- Internet Polling ActivityDocument1 pageInternet Polling Activitycsj6363No ratings yet

- 2012 Presidential Election AssignmentDocument1 page2012 Presidential Election Assignmentcsj6363No ratings yet

- VotingDocument21 pagesVotingcsj6363No ratings yet

- Propaganda Techniques 2011Document12 pagesPropaganda Techniques 2011csj6363No ratings yet

- Mass MediaDocument14 pagesMass Mediacsj6363No ratings yet

- Electoral College Reform ArticleDocument3 pagesElectoral College Reform Articlecsj6363No ratings yet

- Primary Election ArticleDocument1 pagePrimary Election Articlecsj6363No ratings yet

- Election ProcessDocument19 pagesElection Processcsj6363No ratings yet

- Political Party Platform AssignmentDocument1 pagePolitical Party Platform Assignmentcsj6363No ratings yet

- Political Parties Good or Bad ArticleDocument3 pagesPolitical Parties Good or Bad Articlecsj6363No ratings yet

- RA 10151 Allows Night Work, Benefits Call Center AgentsDocument16 pagesRA 10151 Allows Night Work, Benefits Call Center AgentsAshley CandiceNo ratings yet

- Sanchez v. COMELEC, G.R. Nos. 78461, 79146, 79212, (1987)Document30 pagesSanchez v. COMELEC, G.R. Nos. 78461, 79146, 79212, (1987)Ayo LapidNo ratings yet

- American Gov. Final Exam and Essay GuideDocument6 pagesAmerican Gov. Final Exam and Essay GuideiamsmoothNo ratings yet

- Voeltz V Obama - Obama ID Fraud Case - Florida Ballot Challenge - 1/2014Document19 pagesVoeltz V Obama - Obama ID Fraud Case - Florida Ballot Challenge - 1/2014ObamaRelease YourRecordsNo ratings yet

- Auro SolvoDocument226 pagesAuro SolvoNandhi VarmanNo ratings yet

- Constitution & Bill of RightsDocument15 pagesConstitution & Bill of RightsAnonymous puqCYDnQ100% (3)

- Environmental Chemistry 10th Manahan Solution ManualDocument36 pagesEnvironmental Chemistry 10th Manahan Solution Manualoutformimperialbi45100% (39)

- Howard Berg Study 1 & 2 Reference Guide PDFDocument52 pagesHoward Berg Study 1 & 2 Reference Guide PDFImranKhalid100% (1)

- Santiago V Guingona - Rule 66 Quo WarrantoDocument2 pagesSantiago V Guingona - Rule 66 Quo Warrantobebs CachoNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry 8th Edition Campbell Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesBiochemistry 8th Edition Campbell Solutions Manualagleamamusable.pwclcq100% (25)

- ABAKADA Guro Party List vs. Executive Secretary Ermita: Constitutionality of Sections 4, 5, and 6 of RA 9337Document3 pagesABAKADA Guro Party List vs. Executive Secretary Ermita: Constitutionality of Sections 4, 5, and 6 of RA 9337Samantha ReyesNo ratings yet

- SH0421Document20 pagesSH0421Anonymous 9eadjPSJNgNo ratings yet

- PPGC - Group 1 - Week 7Document45 pagesPPGC - Group 1 - Week 7svurbina3934valNo ratings yet

- David M. Dodge - The Missing 13th AmendmentDocument22 pagesDavid M. Dodge - The Missing 13th AmendmentJohn Sutherland100% (4)

- Supreme Court ruling details controversial Philippine land dealsDocument18 pagesSupreme Court ruling details controversial Philippine land dealsChingNo ratings yet

- XcalvDocument10 pagesXcalvlosangelesNo ratings yet

- Tolentino V Comelec Case DigestDocument1 pageTolentino V Comelec Case DigestRodrigo Agustine CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Taxation PDFDocument118 pagesTaxation PDFMary DenizeNo ratings yet

- PHILCONSA v. Mathay: Term expiration of all Congress members needed before salary increase takes effectDocument2 pagesPHILCONSA v. Mathay: Term expiration of all Congress members needed before salary increase takes effectGelay PererasNo ratings yet

- Congressional Privileges, Rules on Lawmaking & Member DisciplineDocument13 pagesCongressional Privileges, Rules on Lawmaking & Member DisciplineJoshuaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 173264 - Civil Service Commission v. Javier PDFDocument15 pagesG.R. No. 173264 - Civil Service Commission v. Javier PDFMae ReyesNo ratings yet

- The Rules of The Texas Democratic PartyDocument28 pagesThe Rules of The Texas Democratic PartyTom BlNo ratings yet

- 2010 State of The UnionDocument7 pages2010 State of The UnionWayne EvelandNo ratings yet

- Senate vs. Ermita (G.R. No. 169777) - Digest FactsDocument9 pagesSenate vs. Ermita (G.R. No. 169777) - Digest Factsaquanesse21No ratings yet

- Aytona Vs CastilloDocument19 pagesAytona Vs CastilloSapphireNo ratings yet

- February 11, 2015 Tribune Record GleanerDocument24 pagesFebruary 11, 2015 Tribune Record GleanercwmediaNo ratings yet

- 2.enrile Vs Amin-DigestDocument2 pages2.enrile Vs Amin-Digestdarren gonzalesNo ratings yet

- Ampongan vs. SB 2019Document21 pagesAmpongan vs. SB 2019hlcameroNo ratings yet

- 30 - Tanada v. Cuenco, 103 Phil. 1051 (1957)Document47 pages30 - Tanada v. Cuenco, 103 Phil. 1051 (1957)Elle AlamoNo ratings yet

- ABAKADA Guro Party List Vs Executive Secretary ErmitaDocument3 pagesABAKADA Guro Party List Vs Executive Secretary ErmitaAnonymous iUs2y1vNNo ratings yet