Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Church Going

Uploaded by

Mosharraf Hossain SylarOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Church Going

Uploaded by

Mosharraf Hossain SylarCopyright:

Available Formats

"Church Going" and "Westminster Abbey" Summary: poets' John Betjeman and Philip Larkin in their The poems

"In Westmin ster Abbey" and "Church Going" treat the theme of religion as a disrespectful id eology which is not worth believing or mentioning. Religion is viewed as an inve ntion of the church in order to control the population. The poets take an almost protective stand in defence of readers from religion and superstition. Discuss the poets' treatment of the theme of religion in "Church Going" and "In Westminster Abbey." Both poets' John Betjeman and Philip Larkin in their poems "In Westminster Abbey " and "Church Going", treat the theme of religion as a disrespectful ideology wh ich is not worth believing or mentioning, as it has been for centuries the way i n which the church controlled the people. Throughout "Westminster Abbey" the description and language used by the poet cre ates an ironic atmosphere that is the first point to consider that shows that th e poet does not see church as a serious matter. The poem is written in the voice of a medium to high classed women who believes to have the right to command god and order him as if it were a servant. It seems to the reader that the only real cause for the women to be religious is to try to take benefit, to be protected by God from war and from everything els e, which could harm her. The arrogance and selfishness of the women can be seen as the way the poet expresses his feelings and thoughts about church, religion, believe and God. The poet expresses his ideas and sees religion as an invention of Church in order to control the population. The poet seems to have no belief t owards religion what so ever; he sees it as an obstacle that only benefits the w ealthy. The irony of the poem is further emphasized by the structure of the poem, a trad itional hymn. John Betjeman shows the woman as not only a selfish person but als o a racist who believes that her race is superior. "Gracious Lord, oh bomb the G ermans" "And, even more, protect the whites." This may have been intentionally i ncluded to show that the rich were not only the ones who favored most from the c hurch, but also the most selfish. In "Church Going", the poet expresses the same disrespectfulness towards church as "In Westminster Abbey." The Church, also known as the house of God, is seen by the poet as a current bui lding and all being alike, "another church: matting, seats, and stone..." some b rass and stuff" which gives the reader a very dismissive attitude from the poet. He agrees with Betjeman that the church disserves no believe or respect "Hatles s, I take off my cycle-clips in awkward reverence." Instead of commenting on the beauty of the church, he looks at the roof asking h imself if it is "cleaned, or restored"" It seems that the poet is even more disr espectful than Betjeman donating an Irish sixpence and then further emphasizing, "reflect the place was not worth stopping for." The poet is for sure that churches will fall down except for some, which will be kept as a chronic symbol where women will bring their children to touch a parti cular stone believing that they will work as a spell. His opinion is that "super stition, like belief, must die." This supposes a strong blow against the church and towards believe. Philip Larkin asks himself who will be the last to see the church before it dete riorates completely "some ruin-bibber" some "Christmas-addict" someone obsessed with church or someone just like him who has no believe or sympathy with the chu rch. For the poet, the church is the place of marriage, birth and death and believes that that causes people to become fanatic towards church because they see it as the place that marks the most important points of life. Larkin also sees the church trying to make people see natural things of life suc h as birth and having children as being in their destiny and that people will al ways look for the spiritual side. In conclusion, I would say that the poets are conscious of the poetic diction th ey use in order to bring through their feelings about the church. They do not se

e any reason or need for which religion and believe exist and want superstition to be gotten rid of. They see the Church as a place, which manipulates people fo r their own benefit. The use of less poetic devices such as "oh bomb the Germans" in "In Westminster Abbey" or "bored, uniformed, knowing the ghostly silt" in "Church Going" does no t suggest that this in any way makes the poems less "poetic" in any sense at all . John Betjeman and Philip Larkin seem to be wanting the readers to be aware of the church and protect them from it. Firstly, the title is worthy of examination. Deceptively simple, the title "Chur ch Going" is very clever as it has two interpretations. The first refers to the act of weekly worship, usually on a Sunday, and Phillip Larkin will go on to con sider the traditions and future potential of this practice. The second interpret ation in the word "going" refers to the action of the buildings and institutions themselves and which way they will be going in the future. Larkin lays out his thoughts about this as the poem develops, and his prognosis is not good. He view s the churches as falling into disrepair as society moves on from blind adherenc e to religion, and wonders where it will all lead. He imagines in his mind's eye , the churches as ruins with weeds and grass growing up between the floor slabs and wonders whether anyone will want to buy them and what use they might put the buildings to. The tone of the poem engages the reader in a sort of conversation with the poet as he thinks aloud in the inhibiting silence of the musty old building. We are d eliberately told that, even for Larkin himself, his visit to the church is just an add-on, a convenient stop-off on a cycling trip. With the first words of the poem being:"Once I am sure there's nothing going on I step inside, letting the d oor thud shut. "Larkin puts readers in a particular spot in time, as if they to o, had come along with the poet for the ride, and are breaking their journey wit h him. He uses a curiously detached and objective tone, however, as if he is an outsider in the church looking in at the practice of religious observation as if he has no role in it. He emphasizes this with the word "hatless" as he disregar ds this mark of respect. Language such as "brownish" and "musty" illustrate his view that the church is past its best, and may one day be totally obsolete, and contribute to the themes of Time, Religion, Function and Society. Overall, Phillip Larkin's message seems to be that in the future churches will e ither decay into ruins or be put to other more materialistic uses such as homes or retail outlets. Even in the present time, he wonders whether their only autho rity and atmosphere of awe comes from the fact that there are so many dead in th e vicinity. Philip Larkins Church Going describes the idle curiosity of the poet/speaker for a church he comes across while out for a bike ride. It consists of 7 stanzas, ea ch 9 lines in length.The meter is a relaxed iambic pentameter. The rhyme scheme is ababcbdgb with numerous slant rhymes appearing in lines 5 9. The language is typical of Larkin - ordinary, conversational, almost slangy. The speaker wants to be sure there is nothing in the way of a church service go ing on. He appears more interested in the building than in the movement that bro ught it about. He demonstrates awkward reverence removing his hat and cuff clips . Apparently he has stopped at a number of churches. He describes this one as Ano ther church and makes note of matting, seats, and stone,/ And little books, spraw lings of flowers cut/ For Sunday, brownish now. He seems uninterested in the deno mination of the church. In stanza 2 he moves forward, rubbing a hand over the baptismal font, speculating on the condition of the roof, climbs the lectern and says, Here endeth more loudly than he had intended to. Returning to the entrance, he signs the guest book and contributes a foreign coin to the collection box, t hinking the place was not worth stopping for. In stanza 3 he questions his curious habit of stopping at churches. Once they have become totally useless, will officials keep open some cathedrals and leave the smaller churches to rain and sheep? Will cathedrals become tourist traps and these smaller churches become attractions for ruin seekers, antique hounds, and

mothers perpetuating superstitions and seeking simples (medicinal plants) to cu re cancer? It becomes clear that the title has more than one meaning. Churches were built for the once large numbers of believers who attended every Sunday, but those num bers are rapidly reducing themselves. Marriages are gradually shifting to legal events performed by lay people if indeed people dont merely choose to live toget her without ceremony. The same situation is replacing the elaborate requiems and funerals of earlier ages. As time goes on, the Church is playing a role of less importance in society, politics, and world events. Finally there are people lik e the poet/speaker - curious but not trained in history or architecture who are church goers but are unencumbered by religion. The Church may be said to be going fast. Still Larkins speaker (who speaks for L arkin) cannot totally reject the human religious movement that dominated history until the twentieth century. A serious house on serious earth it is. And think of all the many dead who lie round. Ambulances Stanza One. The opening words of the first stanza describe the ambulance as a "closed confes sional," if you think about those two words then nothing could be more true. A person in pain or distress is so very vulnerable and at that point in their li fe they may freely give away information that they would have normally held clos e to their chest. Personal information is always exchanged between a patient and the ambulance crew. The ambulance is referred to as the glossy light grey vehicle with the county ba dge painted onto the side of it. As the ambulance makes its way through the busy city with its siren shrieking many people on the streets will turn to look and to wonder where it is going. From this we can deduce that the patient lives on t he outskirts of a busy city and the fact that he is a number rather than a name because city life often tends to be rather impersonal. Larkin is perfectly correct when he states that the ambulance is immune to the o nlookers, the driver of the vehicle is only concerned with reaching his destinat ion. Larkin points out that the ambulance could be called anywhere, any place or any time, not one of us can know when or of we will find ourselves in a similar situ ation. These are the opening lines of the poem and by the time you have read them you w ill know that the verse is not upbeat or optimistic. The air is hanging with imp ending doom and gloom. Stanza Two. The emergency clearly happens around lunchtime, maybe Larkin decided this poem s hould be set during the school holidays because he refers to the children playin g on the the streets. The reference to the children playing on the streets instantly makes you realise that this poem was written a few decades ago, streets are no longer a safe plac e for children to play. The patient is clearly very distressed, Larkin describes his face as "wild and w hite face." But life goes on as the frightened and bewildered patient is put onto the stretc her and covered with the blood red blanket. One of the residents of the street may well be in dire distress but the saucepan s still remain on top of the stove and that instantly reminds me of the wartime years when women would refuse to go into the air-raid shelters because their mea ls would burn. Up until now we have no idea whether the patient is male, female, young or elder ly. Larkin is keeping us in the dark. Stanza Three. In this stanza there is an air of total despair. Larkin says, "And sense the solving emptiness that lies just under all we do." It seems that Larkin is implying that life is futile, he may even be thinking th

at death is preferential to life. And for a second get it whole, so permanent and blank and true. Death is the final chapter, it is permanent. Larkin makes sure that we know that the neighbours are upset by the scene and as the patient is finally stowed away inside of the glossy grey ambulance then and only then do they feel able to sympathise with the whole situation. It seems th at the neighbours watch on but none of them want to get involved. We must take i t that the patient travels to the hospital on his/her own, there is never any me ntion of anyone else. Stanza Four. The next couple of lines give us great insight into how serious the situation is , Larkin speaks of the "deadened air," "the sudden shut of loss" and " something nearly at an end." So from these words we can glean that the patient is making his final journey. Only at that point do you see the word "family" appear but La rkin seems to be referring to previous life when there was some cohesion. Life i s slowly drifting away and the tone of the verse has all but come to a halt. Stanza Five. There is great sorrow in the next few lines and that sorrow is so tangible that it could lead you to think that Larkin was wondering about his own death. "Death is imminent, the patient lays alone and has no one to share his final moments w ith." As the siren wails and the ambulance nears the hospital entrance the traff ic senses the emergency and hastily pulls over to let the racing vehicle past. T he penultimate line is "Brings closer what is life to come." Does this mean that Larkin believed in the afterlife? For me those few words inject a sense of hope but in the final line "And dulls to distance all we are," my hopes are dashed a gainst the rocks. "Ambulances" by Philip Larkin is a very astute observation of life.

AMBULANCES Philip Larkin A meditation on the closeness of death, its randomness and its inevitability. Th ese three ideas are captured for Larkin in the action of ambulances in the city. Today young people might see ambulances as a sign of hope, a positive intervent ion sustaining life rather than heralding death. When the poem was written in th e fifties, to be carried away in an ambulance was a sign of worse to come. Stanza 1 The ambulances symbolise death. They are closed and inscrutable giving back none of the glances they absorb; like a corpse. They are private, secretive, silent li ke confessionals. They cause agitation in people who glance nervously at them ho ping that their time has not come. The randomness of death is suggested by They come to rest at any kerb Its inevitability is expressed in, all streets in time are visited Stanza 2 Note Larkins superb eye for significant detail as he points out the contrast betw een the zest and energy of living children strewn on roads women.past smells of different dinners and the horror of i s opposite A wild white face.. as the patient is carried away from the flow of n ormality to be stowed like some dead thing in the ambulance. The red of the blanke ts, the white of the face are colours of distress. Stanza 3 A reflective stanza after the vivid details of the first two. The poet is moved to think that death is our common fate that has the power to render life meaning less. All our busy concerns, all our cooking, our play is just a way of filling time until death takes us away to empty nothingness; And sense the solving emptiness That lies just under all we do. This thought which we put out of our minds comes to us without any softening the ology And for a second (we) get it whole So permanent and blank and true

As the ambulance pulls away, Larkin suggests that peoples expression of sympathy at the patients plight is also an expression of our common vulnerability to sickn ess and death. Stanza 4 and 5 Now Larkin thinks of the dying patient and the sadness in her heart as she exper iences the sudden shut of loss Round something nearly at an end. He sympathises with her fear. He reflects on the loss that death will bring; how it will destroy this unique person the unique random blend of families and fashions and loosens her from her family and identity - all that really matters to us as people. The tremendous isolation of being in an ambulance as she faces death Far from the exchange of love to lie Unreachable inside a room (i.e. the ambulance) brings ou t Larkins deep sympathy for the victim. This sympathy is for a real person. But as with most poems by Larkin, he is able to take a particular experience, a part icular circumstance and find a general truth in it. Here, the sufferings of the victim become the model for all life lived, all deat h experienced. The model is bleak, however. Living according to this model is ju st the rush towards death, brings closer what is left to come and the effect of t his realisation is to make life seem a lonely and bleak experience robbed of its joyful immediacy its pleasant physicality, And dulls to distance all we are. We a re left isolated by the experience, distanced from ourselves.

You might also like

- CHURCH GOING (Poem) (Philip Larkin)Document8 pagesCHURCH GOING (Poem) (Philip Larkin)Samra Khaliq100% (1)

- Church GoingDocument3 pagesChurch GoingLearn With UsNo ratings yet

- Church Going Critical AppreciationDocument4 pagesChurch Going Critical Appreciationصراطِ مستقيمNo ratings yet

- Mohammad Jafar Iqbal (Port City, M.A. 20th) ENF 020 05003Document9 pagesMohammad Jafar Iqbal (Port City, M.A. 20th) ENF 020 05003Iqbal MohammadjafarNo ratings yet

- A Serious House On Serious Earth It IsDocument3 pagesA Serious House On Serious Earth It Isshah rukhNo ratings yet

- Church GoingDocument7 pagesChurch GoingSaima yasinNo ratings yet

- CG (Poem Analysis)Document10 pagesCG (Poem Analysis)Zenith RoyNo ratings yet

- Church GoingDocument2 pagesChurch GoingUsmanHaiderNo ratings yet

- Church Going by Philip Larkin: ST NDDocument2 pagesChurch Going by Philip Larkin: ST NDkalai nourNo ratings yet

- Larkin's "Church Going" Carefully Balances Agnostic Dissent With An Insistence On Saving The Spirit of Tradition Which Reflects Secular AnglicanismDocument3 pagesLarkin's "Church Going" Carefully Balances Agnostic Dissent With An Insistence On Saving The Spirit of Tradition Which Reflects Secular AnglicanismIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Church GoingDocument7 pagesChurch GoingRachitaNo ratings yet

- Churuch GoingDocument5 pagesChuruch GoingGum NaamNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Prose & Poetry: Course Code:-ENG607Document3 pagesContemporary Prose & Poetry: Course Code:-ENG607Sabab ZamanNo ratings yet

- Church GoingDocument2 pagesChurch GoingNadeem ul Hassan100% (1)

- Christianity and “the World”: Secularization Narratives through the Lens of English Poetry 800 AD to the PresentFrom EverandChristianity and “the World”: Secularization Narratives through the Lens of English Poetry 800 AD to the PresentRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Postwar Poetry BritishDocument5 pagesPostwar Poetry BritishKittiNo ratings yet

- Themes in Philip LarkinDocument5 pagesThemes in Philip LarkinSana RaoNo ratings yet

- Church Going 1Document2 pagesChurch Going 1KabraNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Church Going by Philip Larkin and Christmas by John Betjeman-1Document3 pagesA Comparison of Church Going by Philip Larkin and Christmas by John Betjeman-1Ritankar RoyNo ratings yet

- Themes in LarkinDocument10 pagesThemes in LarkinFarah Saeed100% (3)

- Why We'll Always Ask Big QuestionsDocument7 pagesWhy We'll Always Ask Big QuestionsHaroon AslamNo ratings yet

- Church GoingDocument7 pagesChurch Goingtiadaga845No ratings yet

- The Habit of Poetry: The Literary Lives of Nuns in Mid-century AmericaFrom EverandThe Habit of Poetry: The Literary Lives of Nuns in Mid-century AmericaNo ratings yet

- Philip LarkinDocument22 pagesPhilip LarkinHarini IyengarNo ratings yet

- Analysis: Church GoingDocument7 pagesAnalysis: Church GoingYasir JaniNo ratings yet

- Analysis: Church GoingDocument7 pagesAnalysis: Church GoingPritam SinghaNo ratings yet

- A Heart Lost in Wonder: The Life and Faith of Gerard Manley HopkinsFrom EverandA Heart Lost in Wonder: The Life and Faith of Gerard Manley HopkinsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Liturgical Liaisons: The Textual Body, Irony, and Betrayal in John Donne and Emily DickinsonFrom EverandLiturgical Liaisons: The Textual Body, Irony, and Betrayal in John Donne and Emily DickinsonNo ratings yet

- A Darkened Reading: A Reception History of the Book of Isaiah in a Divided ChurchFrom EverandA Darkened Reading: A Reception History of the Book of Isaiah in a Divided ChurchNo ratings yet

- Themes in Philip LarkinDocument7 pagesThemes in Philip Larkinmanazar hussain100% (1)

- Philip Larkin Use of IronyDocument14 pagesPhilip Larkin Use of IronySumaira Malik100% (3)

- Philip Larkin Church Going AnalysisDocument1 pagePhilip Larkin Church Going AnalysisViktória Hamar50% (2)

- Beyond the Cloister: Catholic Englishwomen and Early Modern Literary CultureFrom EverandBeyond the Cloister: Catholic Englishwomen and Early Modern Literary CultureNo ratings yet

- Suspicious Moderate: The Life and Writings of Francis à Sancta Clara (1598–1680)From EverandSuspicious Moderate: The Life and Writings of Francis à Sancta Clara (1598–1680)No ratings yet

- PessimismDocument5 pagesPessimismNadeem ul HassanNo ratings yet

- Written Analysis of A Poem - Water' by Philip LarkinDocument3 pagesWritten Analysis of A Poem - Water' by Philip LarkinDilek MustafaNo ratings yet

- The Way of a PilgrimFrom EverandThe Way of a PilgrimNina A ToumanovaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- Studies in Religion and Literature (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandStudies in Religion and Literature (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- Philip Arthur LarkinDocument9 pagesPhilip Arthur Larkinkfülöp_8No ratings yet

- If Is the Only Peacemaker: The Catholic Humanist Rhetoric of As You Like ItFrom EverandIf Is the Only Peacemaker: The Catholic Humanist Rhetoric of As You Like ItNo ratings yet

- Cathedrals of Bone: The Role of the Body in Contemporary Catholic LiteratureFrom EverandCathedrals of Bone: The Role of the Body in Contemporary Catholic LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Philip Larkin PoetryDocument11 pagesPhilip Larkin Poetryrok mod100% (1)

- PPT4 UNITIIDocument13 pagesPPT4 UNITIIMunzir HassanNo ratings yet

- Sir MohsinDocument8 pagesSir MohsinFariha Younas DarNo ratings yet

- Treasure in Heaven: The Holy Poor in Early ChristianityFrom EverandTreasure in Heaven: The Holy Poor in Early ChristianityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Notes On John Keble and The True Spirit of Catholic ImaginationDocument3 pagesNotes On John Keble and The True Spirit of Catholic ImaginationTim GadenNo ratings yet

- Criticism of the Church in Chaucer's TalesDocument5 pagesCriticism of the Church in Chaucer's TalesPau ArlandisNo ratings yet

- Look Back in AngerDocument1 pageLook Back in AngerMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

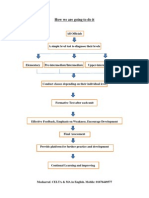

- How We Are Going To Do ItDocument2 pagesHow We Are Going To Do ItMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- The Continuum of Teacher LearningDocument5 pagesThe Continuum of Teacher LearningMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Maritime College: CENTRE NO:93318Document8 pagesCambridge Maritime College: CENTRE NO:93318Mosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Discussion QuestionsDocument1 pageDiscussion QuestionsMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- TKT Unit 10: Exposure and Focus On Form: by Md. Mosharraf HossainDocument10 pagesTKT Unit 10: Exposure and Focus On Form: by Md. Mosharraf HossainMosharraf Hossain Sylar100% (1)

- 03 Talking About TravelDocument1 page03 Talking About TravelMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Discussion QuestionsDocument1 pageDiscussion QuestionsMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- 04 Making Plan For The WeekendDocument1 page04 Making Plan For The WeekendMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Misconception About IELTSDocument4 pagesMisconception About IELTSMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Maritime College English ExamDocument5 pagesCambridge Maritime College English ExamMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Brian Patten The Minister For ExamsDocument2 pagesBrian Patten The Minister For ExamsMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- StoriesDocument1 pageStoriesMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- The Continuum of Teacher LearningDocument5 pagesThe Continuum of Teacher LearningMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Overseas Postgraduate Info 2012Document3 pagesOverseas Postgraduate Info 2012Mosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Misconception About IELTSDocument4 pagesMisconception About IELTSMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- The Continuum of Teacher LearningDocument5 pagesThe Continuum of Teacher LearningMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- How Teachers LearnDocument4 pagesHow Teachers LearnMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- How Teachers LearnDocument4 pagesHow Teachers LearnMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- English QuestionDocument5 pagesEnglish QuestionMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Book ListDocument1 pageBook ListMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire For Viva 30 December 2012Document1 pageQuestionnaire For Viva 30 December 2012Mosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Ban Glades Hi ELT TeachersDocument5 pagesBan Glades Hi ELT TeachersMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Learner Centered ActivityDocument2 pagesLearner Centered ActivityMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- PragmatismDocument18 pagesPragmatismMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Waiting For Godot and The Existential Theme of Absurdity 2 PPDocument3 pagesWaiting For Godot and The Existential Theme of Absurdity 2 PPMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Learner Centered ActivityDocument2 pagesLearner Centered ActivityMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- Einstein GandhiDocument10 pagesEinstein GandhiMosharraf Hossain SylarNo ratings yet

- A Look at Sinners in The Hands of An Angry God by Jonathan EdwardsDocument2 pagesA Look at Sinners in The Hands of An Angry God by Jonathan EdwardsMosharraf Hossain Sylar100% (1)

- Pessimistic Worldview and Existential Nihilism in Philip Larkin's Poetry-TCLDocument12 pagesPessimistic Worldview and Existential Nihilism in Philip Larkin's Poetry-TCLJyotsna singh100% (1)

- J.Weiner. The Whitsun WeddingsDocument5 pagesJ.Weiner. The Whitsun WeddingsОля ПонедильченкоNo ratings yet

- Religion EssayDocument3 pagesReligion EssayIsabelle BullmanNo ratings yet

- CHURCH GOING INSIGHTDocument6 pagesCHURCH GOING INSIGHTThe True NoobNo ratings yet

- NCERT Class 11 English Elective ComingDocument2 pagesNCERT Class 11 English Elective ComingAbhishek MandalNo ratings yet

- Church GoingDocument12 pagesChurch GoingImman GhazanfarNo ratings yet

- Philip Larkin's Concept of Time As Projected in His Poetry: A Brief AnalysisDocument5 pagesPhilip Larkin's Concept of Time As Projected in His Poetry: A Brief AnalysisNethuli KiaraNo ratings yet

- Larkin's "The North ShipDocument3 pagesLarkin's "The North Shipsk moinul hasanNo ratings yet

- Life and Death in Philip Larkin's Poetry:an Analytical Study ofDocument28 pagesLife and Death in Philip Larkin's Poetry:an Analytical Study ofAli Mohamed100% (1)

- Critical Assessment of Poetry of Philip LarkinDocument6 pagesCritical Assessment of Poetry of Philip LarkinIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Larkin and The MovementDocument13 pagesLarkin and The MovementTóth Zsombor100% (2)

- Faith Healing: Larkin's Critique of Religion as an InstitutionDocument2 pagesFaith Healing: Larkin's Critique of Religion as an InstitutionPranvera KameriNo ratings yet

- Aubade by Philip Larkin - Poetry FoundationDocument3 pagesAubade by Philip Larkin - Poetry FoundationdevonchildNo ratings yet

- Irony, LarkinDocument2 pagesIrony, LarkinDevolina DasNo ratings yet

- Church Going by Philip Larkin - Poem AnalysisDocument21 pagesChurch Going by Philip Larkin - Poem Analysisworld UNONo ratings yet

- Larkin, Philip - Art of Poetry, The (Paris Review, Summer 1982)Document26 pagesLarkin, Philip - Art of Poetry, The (Paris Review, Summer 1982)Dhirendra Kumar ShahNo ratings yet

- Depiction of Modern Man in "Church Going" by Philip Larkin: A Case Study Through ModernismDocument6 pagesDepiction of Modern Man in "Church Going" by Philip Larkin: A Case Study Through ModernismTasawar AliNo ratings yet

- Larkin Ambulances1Document4 pagesLarkin Ambulances1Sumaira MalikNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document37 pagesPresentation 1nadieh_baderkhaniNo ratings yet

- TNTDocument1 pageTNTPiyush Bisht100% (1)

- K-0415 (Paper-III) (English)Document16 pagesK-0415 (Paper-III) (English)lanememory09No ratings yet

- Philip Larkin's Poetic CredoDocument6 pagesPhilip Larkin's Poetic CredoConny DorobantuNo ratings yet

- British Poetry After 1945Document12 pagesBritish Poetry After 1945Claire ZahraNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Themes of DeathDocument7 pagesAn Analysis of The Themes of DeathJauhar Jauharabad100% (2)

- Dr. DHANYA MENON 1-3Document3 pagesDr. DHANYA MENON 1-3Dreamcatcher DreamcatcherNo ratings yet

- Churuch GoingDocument5 pagesChuruch GoingGum NaamNo ratings yet

- Larkin - As A PoetDocument6 pagesLarkin - As A PoetGum Naam100% (3)

- Authorial Presence in PoetryDocument32 pagesAuthorial Presence in PoetryAndreeaMateiNo ratings yet

- Poetry Analysis Toads Philip LarkinDocument2 pagesPoetry Analysis Toads Philip LarkinNìcolaScaranoNo ratings yet