Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wegener's Continental Drift Theory challenged scientific establishment

Uploaded by

siddiqueaquibOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wegener's Continental Drift Theory challenged scientific establishment

Uploaded by

siddiqueaquibCopyright:

Available Formats

Wegener and Continental Drift Theory

How we interpret the science of centuries past cannot be separated from our view of modern science. The danger is that this view may be based on a stereotype. A common stereotype of a scientist is that of a rational professional that evaluates new ideas based only on an objective evaluation of data. This would leave the impression that, unlike early scientists, modern scientists proposing radical new ideas do not need to fear the reactions of those entrenched in the existing system. Alfred Wegener is one modern scientist amongst many that demonstrate that new ideas threaten the establishment, regardless of the century. Alfred Wegener was the scientist who championed the Continental Drift Theory through the first few decades of the twentieth century. Simply put, his hypothesis proposed that the continents had once been joined, and over time had drifted apart. The jigsaw fit that the continents make with each other can be seen by looking at any world map. The image below shows the continents of Africa and South America joined together. Clicking on the image will illustrate their drift to their current positions (thanks are due NASA for the original images).

Wegener and his Critics

Since his ideas challenged scientists in geology, geophysics, zoogeography and paleontology, it demonstrates the reactions of different communities of scientists. The reactions by the leading authorities in the different disciplines was so strong and so negative that serious discussion of the concept stopped. One noted scientist, the geologist Barry Willis, seemed to be speaking for the rest when he said: further discussion of it merely incumbers the literature and befogs the mind of fellow students. Barry Willis's and the other scientists wishes were fulfilled. Discussion did stop in the larger scientific community and students' minds were not befogged. The world had to wait until the 1960's for a wide discussion of the Continental Drift Theory to be restarted. Why did Alfred Wegener's work produce such a reaction? He was much more diplomatic in presenting his theory than Galileo. Although he believed himself to be right and that some of his arguments were compelling, he knew he would need more support to convince others. His immediate goal was to have the concept openly discussed. Wegener did not even present Continental Drift as a proven theory. These modest goals did not spare him. The fact that his work crossed disciplines exposed him to the territoriality of scientific disciplines. The authorities in the various disciplines attacked him as an interloper that did not fully grasp their own subject. More importantly however, was that even the possibility of Continental Drift was a huge threat to the established authorities in each of the disciplines.

One can't underestimate the effect of a radical new viewpoint on those established in a discipline. The authorities in these fields are authorities because of their knowledge of the current view of their discipline. A radical new view on their discipline could be a threat to their own authority. One of Alfred Wegener's critics, the geologist R. Thomas Chamberlain, could not have summarized this threat any better : "If we are to believe in Wegener's hypothesis we must forget everything which has been learned in the past 70 years and start all over again." He was right.

Continental Drift

Theory:Building the Case

In spite of the criticisms from several different disciplines Wegener was able to keep Continental Drift part of the discussion until his death. He knew that any argument based simply on the jigsaw fit of the continents could easily be explained away as a coincidence. To strengthen his case he drew from the fields of geology, geography, biology and paleontology. Wegener questioned why coal deposits, commonly associated with tropical climates, would be found near the North Pole and why the plains of Africa would show evidence of glaciation. Wegener also presented examples where fossils of exactly the same prehistoric species were distributed where you would expect them to be if there had been Continental Drift (e.g. one species occurred in western Africa and South America, and another in Antartica, India and central Africa) [_1_] . The graphic below shows the striking distribution of fossils on the different continents.

Wegener used an Alexander duToit graphic to demonstrate the uncanny match of geology between eastern South America and western Africa.

Continental Drift Theory:The Fatal Flaw

Thus far the picture painted of Alfred Wegener's contemporaries is not flattering. But this might be unfair. One would expect some scientists to resist ideas that would invalidate their life's work. But it doesn't explain all criticism of Wegener's ideas. Wegener presented very compelling arguments for Continental Drift but there were alternate explanations for some of his observations. To explain the unusual distribution of fossils in the Southern Hemisphere some scientists proposed there may once have been a network of land bridges between the different continents. To explain the existence of fossils of temperate species being found in arctic regions, the existence of warm water currents was proposed. Modern scientists would look at these explanations as even less credible than those proposed by Wegener, but they did help to preserve the steady state theory. New theories donot always arrive with all the t's crossed and i's dotted. Wegener did not have an explanation for how continental drift could have occurred. He proposed two different mechanisms for this drift, one based on the centrifugal force caused by the rotation of the earth and a 'tidal argument' based on the tidal attraction of the sun and the moon. These explanations could easily be proven inadequate and opened Wegener to ridicule because they were orders of magnitude too weak. Wegener really did not believe that he had the explanation for the mechanism, but that this should not stop discussion of a hypothesis. The scientists of the time disagreed. After Alfred Wegener died, the Continental Drift Theory was quietly swept under the rug. With the Continental Drift

Theory out of the way, the existing theories of continent formation were able to survive, with little challenge until the 1960's.

Wegener and Darwin

The main problem with Wegener's hypothesis of Continental Drift was the lack of a mechanism. He did not have an explanation for how the continents moved. Some argue that this failing justified the early reactions to his work and to its dismissal. But Charles Darwin was missing a mechanism for the inheritance of beneficial traits when he published the Origin of Species in 1859. Darwin had amassed a huge amount of evidence that supported some type of adaptive process that contributed to the evolution of new species, much like Wegener had for Continental Drift. He argued that with the natural variations that occur in populations, any trait that is beneficial would make that individual more likely to survive and pass on the trait to the next generation. If enough of these selections occured on different beneficial traits you could end up with completely new species. One major flaw in Darwin's theory was that he did not have a mechanism for how the traits could be preserved over the succeeding generations. At the time, the prevailing theory of inheritance was that the traits of the parents were blended in the offspring. But this would mean that any beneficial trait would be diluted out of the population within a few generations. This is because most of the blending over the next generations would be with individuals that did not have the trait. In spite of the lack of a mechanism for the preservation of traits, Darwin's theory quickly came to dominate. Within 5 years, Oxford University was using a biology textbook that discussed biology in the context of evolution by natural selection. The textbook stated, "Though evidence might be required to show that natural selection accounts for everything ascribed to it, yet no evidence is required to show that natural selection has always been going on, is going on now, and must ever continue to go on. Recognizing this is an a priori certainty, let us contemplate it under its two distinct aspects." At Oxford, evolution by natural selection had gone from hypothesis to a priori certainty in the space of 5 years. In this case the scientific community (excepting a minority of skeptics) chose to ignore the lack of mechanism. Wegener had no such luck with his Continental Drift Theory. [_2_] . The mechanism necessary to explain the preservation of beneficial traits was published shortly after the Origin of Species. Unfortunately it was largely ignored. In 1865, an obscure Augustinian monk from Moldavia presented a paper to the Natural History Society of Brunn where he discussed the results of experiments on pea plants. The results presented by this monk, Gregor Mendel, pointed to traits being inherited 'whole' (also known as particulate inheritance), and that certain traits (recessive traits) that disappear in one generation can reappear in a following generation (see Saving Darwin). This would have gone a long way in plugging at least one hole in the Darwin's theory. Mendel's work was largely ignored until about 1900. Shortly afterward it was incorporated into our modern view of evolution by natural selection known as the 'modern synthesis'. About 2 years before his death, Darwin received a book on hybridization by Focke that discussed

the monk's work. It is known that Darwin never read the pages from Focke that discussed Mendel's work. Darwins theory had another problem. His theory proposed a gradual evolution through successive generations. But the fossil record at the time didn't co-operate. There seemed to be a 'explosion' of different life-forms over a relatively short time span (in geologic terms) in the early Cambrian period. There also didn't seem to be any transitional forms of life preceding these species. This eventually became known as the Cambrian Explosion. Darwin himself recognized this as a serious issue with his theory and he discussed it in the Origin of Species. Darwin explained away the problem as a problem with the fossil record and not with his theory. Over the course of the twentieth century, a much better picture of the fossil record of both the Cambrian and Pre-Cambrian eras was developed. The new discoveries made the problem worse. Much worse. In the early twentieth century, the American paleontologist, Charles Walcott, discovered and excavated the Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada. He found 65,000 more specimens of early Cambrian life, many of which were complex multi-celled animals. At the time there still was no evidence of transitional forms in the pre-Cambrian. Only recently have they started discovering isolated examples of moderately complex multicelled animals from the Pre-Cambrian. This still doesn't explain the step-change in the diversity of life-forms in the Cambrian.

Wegener and Galileo

Wegener also shares much in common with Galileo. Wegener probably had at least as strong a case for Continental Drift in 1929 as Galileo had for the Copernican model in 1633. The reason many do not realize this is that the controversy is usually presented as a controversy between Galileo and the Church and not Galileo and other scientists (see Galileo's Battle for the Heavens). As a result most discussions of the early Copernican Model do not even mention any problems associated with the Copernican model. But it was a scientific controversy and it had many of the same elements of the Continental Drift controversy. Galileo had his own 'tidal argument' ; one that was even more embarassing than Wegener's. Galileo argued that the tides were caused by the sun. It is difficult to understand how a great scientist who had spent his youth less than 20 kilometres from the sea would present an argument for Copernicism based on there only being 1 tide per day and where the tides cycle over the year and not over a month. While it took a noted geologist to show that Wegener's tidal argument was ridiculous, Galileo's tidal argument could be challenged by any fisherman or coastal dweller. The tidal argument wasn't the only or the major problem with Galileo's defense of Copernicism. Wegener's critics never presented strong arguments that Continental Drift couldn't have happened or that it wasn't happening. They did show that the mechanism that Wegener suggested was driving Continental Drift was inadequate. The scientists of Galileo's day did have scientifically valid reasons to doubt a moving earth. A moving earth required that a phenomenon known as stellar parallax (see Copernicism and Stellar

Parallax) would be observed . No one in Galileo's day or for two centuries after his death was able to observe this phenomenon. Another argument against Copernicism was very simple and in its own way, empirical. In 1551, only 8 years after Copernicus's death, the Prutenic tables were developed from the Copernican model to predict the positions of stars and planets. There was 80 years of experience in comparing the performance of Copernican-based tables (Prutenic) and Ptolemaic-based tables (Alphonsine). It didn't seem that one was much better than the other. A reasonable conclusion based on this experience is that if the Ptolemaic was wrong, then the Copernican was not right. These scientists did not have computers and advanced statistical techniques to meticulously compare the predictions of the two systems. When these tools arrived in the twentieth century their hunch was proven correct; there wasn't much separating the two systems [_3_] . Today, it is the Keplerian system of planetary motion that is taught in schools, not the Copernican or the Ptolemaic. Galileo knew of Kepler's model and had never accepted it during his lifetime.

Science:A Question of Faith

Science depends on facts. It also depends on reason. But fact and reason alone cannot explain the different reactions to new hypotheses and theories we see in the examples above. They all had some compelling support and some serious shortcomings. Part of the answer may lie in the sociology of groups. Another part lies in simple faith: faith that future scientists will address the shortcomings in the initial theories. With Darwin's theory, the community of scientists were willing to accept the theory based on a faith that the problems with inheritance and the Cambrian Explosion would be dealt with by future scientists. With Wegener, the community of scientists simply did not have the faith that a mechanism would be found to explain the movement of land masses. With Galileo, some had faith that discovering stellar parallax was only a matter of time and others did not. But it is not only the community that requires faith, the champions of these new theories require faith in their ideas, even when facts sometimes contradict their hypotheses. In each case above, there were facts which when combined with the current assumptions of the time clearly contradicted their hypotheses. None of these scientists let those facts deter them. Paul Feyerabend, a modern philosopher of science, presents a similar view, where he argues that science sometimes is required to work "against the facts". One of his key examples, was how the heliocentric universe made less sense than a geocentric universe during Galileo's day given the facts that were available at the time. Given the current controversy over science versus religion, it is amusing that in the early stages of the development of many theories, science is dependent on faith much like religion.

You might also like

- Alfred Wegener's Continental Drift TheoryDocument11 pagesAlfred Wegener's Continental Drift TheoryVirginio MantessoNo ratings yet

- Alfred Wegener: Scientist or PseudoscientistDocument55 pagesAlfred Wegener: Scientist or Pseudoscientistapi-25958671100% (1)

- Evidence For The Movement of Continents On Tectonic Plates Is Now ExtensiveDocument15 pagesEvidence For The Movement of Continents On Tectonic Plates Is Now ExtensiveRhanna Lei SiaNo ratings yet

- The Theory of Continental DriftDocument5 pagesThe Theory of Continental Driftyuiyumi21No ratings yet

- U4 Investigation Library 13pages 082312-2Document13 pagesU4 Investigation Library 13pages 082312-2James JiangNo ratings yet

- 22 Passage 1 - Origin of Species - Continent Formation Q1-13Document6 pages22 Passage 1 - Origin of Species - Continent Formation Q1-13Cương Nguyễn DuyNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Theoretical Population Genetics: With a New AfterwordFrom EverandThe Origins of Theoretical Population Genetics: With a New AfterwordRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Alfred Wegener BioDocument2 pagesAlfred Wegener BiokaerieNo ratings yet

- Taylor HTerry 1984Document244 pagesTaylor HTerry 1984Bautista Mary LeiNo ratings yet

- Pangaea Puzzle ActivityDocument5 pagesPangaea Puzzle ActivityElvira Sta. MariaNo ratings yet

- Design or Ev. BlavatskyDocument51 pagesDesign or Ev. Blavatskyjorge_lazaro_6No ratings yet

- Chapter 05Document43 pagesChapter 05Zyad MâğdyNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Practice Test 22Document18 pagesIELTS Reading Practice Test 22Nguyễn LinhNo ratings yet

- Journal of Paleontology/FossilsDocument22 pagesJournal of Paleontology/FossilsAngelina RandaNo ratings yet

- The Extended Synthesis in Evolutionary BiologyDocument11 pagesThe Extended Synthesis in Evolutionary BiologyRirinNo ratings yet

- Darwin's Influence Shaped Modern ThoughtDocument9 pagesDarwin's Influence Shaped Modern ThoughtMervin Go SoonNo ratings yet

- Darwin SInfluenceonModernLifeDocument5 pagesDarwin SInfluenceonModernLifeGeo BertazzoNo ratings yet

- Evolution Concepts Explained in Biology ChapterDocument36 pagesEvolution Concepts Explained in Biology ChaptergaryNo ratings yet

- Alfred Wegener: Scientist or Pseudoscientist?Document45 pagesAlfred Wegener: Scientist or Pseudoscientist?Ed DalesNo ratings yet

- Dawkins and DarwinDocument4 pagesDawkins and DarwinIyaElagoNo ratings yet

- Plate Tectonics Guide QuestionsDocument4 pagesPlate Tectonics Guide QuestionsJulliette Frances Kyle Tel-eNo ratings yet

- Illogical Geology, the Weakest Point in the Evolution TheoryFrom EverandIllogical Geology, the Weakest Point in the Evolution TheoryNo ratings yet

- Eclipse of DarwinismDocument20 pagesEclipse of DarwinismAlexandraNo ratings yet

- Darwinism - Science Made To Order - 2Document145 pagesDarwinism - Science Made To Order - 2irfanbinismailNo ratings yet

- History of Plate TectonicsDocument4 pagesHistory of Plate TectonicsRobbie MossNo ratings yet

- Darwin/Wallace theory of evolutionDocument3 pagesDarwin/Wallace theory of evolutionedson alayn muñoz quiñonesNo ratings yet

- Pangaea - 7th Grade Science Module 3Document9 pagesPangaea - 7th Grade Science Module 3Bob BuilderNo ratings yet

- Evolution Vs CreationDocument24 pagesEvolution Vs CreationManoj_George_M_7306No ratings yet

- Debate Primer 2Document6 pagesDebate Primer 2allelesnifferNo ratings yet

- Aralin Sa Pagkatuto Bilang 2Document1 pageAralin Sa Pagkatuto Bilang 2maloyNo ratings yet

- Documenting A Paradigm ShiftDocument10 pagesDocumenting A Paradigm ShiftAnthony E. LarsonNo ratings yet

- Zoloogy Report BlindDocument8 pagesZoloogy Report BlindBlind BerwariNo ratings yet

- Alfred Wegener - Continental Drift TheoryDocument177 pagesAlfred Wegener - Continental Drift TheoryDedi Apriadi50% (2)

- Evolution Beliefs EvolveDocument2 pagesEvolution Beliefs Evolvekeith herreraNo ratings yet

- Evolution, The Limbus and Hereditary Evil: by Rev. Mark R. CarlsonDocument24 pagesEvolution, The Limbus and Hereditary Evil: by Rev. Mark R. CarlsonflorareasaNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Practice Test Raining OnlineDocument16 pagesIELTS Reading Practice Test Raining Onlinebhiman bajarNo ratings yet

- Continental Drift EvidenceDocument37 pagesContinental Drift EvidenceTyDolla ChicoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Alfred WegenerDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Alfred Wegenergvzexnzh100% (1)

- Continental Drift TheoryDocument2 pagesContinental Drift TheoryStanley Jones TugasNo ratings yet

- Was the First Craniate on the Road to CognitionDocument17 pagesWas the First Craniate on the Road to CognitionSlopa StefanNo ratings yet

- Abstract For Evolution PaperDocument2 pagesAbstract For Evolution PaperJackNo ratings yet

- Darwin Deleted: Imagining a World without DarwinFrom EverandDarwin Deleted: Imagining a World without DarwinRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

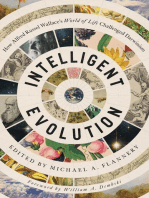

- Intelligent Evolution: How Alfred Russel Wallace's World of Life Challenged DarwinismFrom EverandIntelligent Evolution: How Alfred Russel Wallace's World of Life Challenged DarwinismNo ratings yet

- 02 Chapter Outline - StudentDocument6 pages02 Chapter Outline - StudentDaniel MartinezNo ratings yet

- Uniqueness o Find I 00 Me DaDocument200 pagesUniqueness o Find I 00 Me DaDaniela Nicoleta SbarnaNo ratings yet

- Darwin and Velikovsky : Cataclysmic Metamorphic Evolution a Materialist Theory of Evolution Based on New Principles and EvidenceFrom EverandDarwin and Velikovsky : Cataclysmic Metamorphic Evolution a Materialist Theory of Evolution Based on New Principles and EvidenceNo ratings yet

- Darwin's Theory of EvolutionDocument8 pagesDarwin's Theory of EvolutionRazelle Olendo100% (1)

- Plate - Tectonics - Comprehension ActivityDocument1 pagePlate - Tectonics - Comprehension ActivityTeena SeiclamNo ratings yet

- Alien Mysteries Conspiracies and Cover UDocument4 pagesAlien Mysteries Conspiracies and Cover UGustavo Gabriel CiaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Science Paper - MaheshDocument7 pagesPhilosophy of Science Paper - MaheshMahesh JakhotiaNo ratings yet

- The Survival of The Fittest - Scientific Controversy Fact Sheet - Evolutionism DarwinismDocument8 pagesThe Survival of The Fittest - Scientific Controversy Fact Sheet - Evolutionism Darwinismroan2No ratings yet

- Vedanta and Evolution - Vedanta Kesari - Jan 2009Document4 pagesVedanta and Evolution - Vedanta Kesari - Jan 2009WhirlMind100% (2)

- The Modern Theory of Biological Evolution - An Expanded Synthesis (2004!03!17)Document22 pagesThe Modern Theory of Biological Evolution - An Expanded Synthesis (2004!03!17)Marlon Dag100% (1)

- Enumerate The Lines of Evidence That Support Plate MovementDocument8 pagesEnumerate The Lines of Evidence That Support Plate MovementmtchqnlNo ratings yet

- Wistar DestroysDocument8 pagesWistar Destroysjulianbre100% (1)

- Evolution and Natural SelectionDocument7 pagesEvolution and Natural SelectionMichelleneChenTadleNo ratings yet

- Charles DarwinDocument1 pageCharles DarwinCherrylyn CacholaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 132.174.255.108 On Wed, 15 Feb 2023 14:05:00 UTCDocument35 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 132.174.255.108 On Wed, 15 Feb 2023 14:05:00 UTCAlexandraNo ratings yet

- An Extended Synthesis For Evolutionary BiologyDocument11 pagesAn Extended Synthesis For Evolutionary BiologynataphonicNo ratings yet

- Sustainable ConstructionDocument7 pagesSustainable ConstructionsiddiqueaquibNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Architecture WikiDocument9 pagesSustainable Architecture WikisiddiqueaquibNo ratings yet

- Narmada Bachao AndolanDocument5 pagesNarmada Bachao AndolanGhanshyam DubeyNo ratings yet

- CollectionDocument5 pagesCollectionsiddiqueaquibNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Error - MachDocument431 pagesKnowledge and Error - MachDoda Baloch100% (3)

- Daily Lesson LOG: EN10LC-1a-11.1: EN10RC-1a-2.15.2: EN10LT-1a-14.2: EN10RC-1a-2.15.2Document4 pagesDaily Lesson LOG: EN10LC-1a-11.1: EN10RC-1a-2.15.2: EN10LT-1a-14.2: EN10RC-1a-2.15.2HafsahNo ratings yet

- Longtermem Extremevents PDFDocument21 pagesLongtermem Extremevents PDFJulianna BartalusNo ratings yet

- The Implementation of Critical and Creative Thinking SkillsDocument18 pagesThe Implementation of Critical and Creative Thinking SkillsAswa Amanina Abu ShairiNo ratings yet

- MFL PGCE Resources Vanessa ReganDocument6 pagesMFL PGCE Resources Vanessa Regansamy26rocksNo ratings yet

- Fashiin Show AnchoringDocument3 pagesFashiin Show AnchoringShubhanshi AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of ResearchDocument15 pagesCharacteristics of ResearchcrazygorgeousNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Analysis of Consciousness in AbhidhammaDocument2 pagesBuddhist Analysis of Consciousness in AbhidhammaHoang NguyenNo ratings yet

- 2010 Häuberer, Julia - Social Capital TheoryDocument332 pages2010 Häuberer, Julia - Social Capital TheoryMar Ba SiNo ratings yet

- The NLP Goal Setting Model For ManagersDocument2 pagesThe NLP Goal Setting Model For ManagersDr. Tylor100% (1)

- Strategy Bank - Memory For LearningDocument2 pagesStrategy Bank - Memory For Learningapi-305212728No ratings yet

- Midterm Evaluation W CommentsDocument10 pagesMidterm Evaluation W Commentsapi-313720439No ratings yet

- Educational Theorist Scavenger Hunt 2014Document2 pagesEducational Theorist Scavenger Hunt 2014api-302811772100% (1)

- Pluralisms in Truth and Logic, Jeremy Wyatt, Nikolaj J. L. L. Pedersen, Nathan Kellen (Ed.) PDFDocument483 pagesPluralisms in Truth and Logic, Jeremy Wyatt, Nikolaj J. L. L. Pedersen, Nathan Kellen (Ed.) PDFMarisa Ombra100% (1)

- Barcelo - Computational Intelligence in Archaeology PDFDocument437 pagesBarcelo - Computational Intelligence in Archaeology PDFLupu HarambeNo ratings yet

- Guidelines - Intensive Reading TechniquesDocument3 pagesGuidelines - Intensive Reading TechniquesDavid Woo100% (5)

- Advanced Maintenance ManagementDocument3 pagesAdvanced Maintenance ManagementMohammed Al-OdatNo ratings yet

- Nurse Education Today: Ye Şim Yaman Aktaş, Neziha KarabulutDocument5 pagesNurse Education Today: Ye Şim Yaman Aktaş, Neziha Karabulut하진No ratings yet

- Methods of Aquring KnowledgeDocument8 pagesMethods of Aquring KnowledgeAna Mika100% (2)

- Rating Sheet Teacher I III 051018Document1 pageRating Sheet Teacher I III 051018Jeff Baltazar AbustanNo ratings yet

- Framing TheoryDocument3 pagesFraming TheoryYehimy100% (1)

- Implications of Cognitive Development To Teaching and LearningDocument15 pagesImplications of Cognitive Development To Teaching and LearningAmru Izwan Haidy100% (1)

- Lacan The Number Thirteen and The Logical Form of SuspicionDocument15 pagesLacan The Number Thirteen and The Logical Form of SuspicionGimp LimpNo ratings yet

- Exam in EAPP 2019Document2 pagesExam in EAPP 2019Sumugat TricyNo ratings yet

- Online Free Ebooks Download 40 Paradoxes in Logic Probability and Game TheoryDocument4 pagesOnline Free Ebooks Download 40 Paradoxes in Logic Probability and Game TheoryAshok KumarNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Philo of ReligionDocument15 pagesDoctrine of Philo of ReligionCarlo EmilNo ratings yet

- Writing Assignment 2Document10 pagesWriting Assignment 2Zahiruddin Zahrudin100% (1)

- Professional Education Set 3Document5 pagesProfessional Education Set 3Hanna Grace HonradeNo ratings yet

- TEAM Lesson Plan Template: Knox County SchoolsDocument3 pagesTEAM Lesson Plan Template: Knox County Schoolsapi-379625978No ratings yet

- Bi Cultural in BingliualDocument16 pagesBi Cultural in BingliualTrâm NguyễnNo ratings yet