Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Illinois Catholic Charities Motion To Reconsider, Rehear and Vacate Decision On Foster Care Contracts With State

Uploaded by

Tom CiesielkaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Illinois Catholic Charities Motion To Reconsider, Rehear and Vacate Decision On Foster Care Contracts With State

Uploaded by

Tom CiesielkaCopyright:

Available Formats

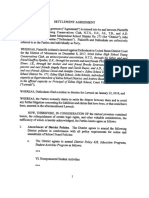

1 of 24 Case No.

2011 MR 254

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT FOR THE SEVENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT

SANGAMON COUNTY, ILLINOIS

CATHOLIC CHARITIES OF THE DIOCESE )

OF SPRINGFIELD-IN-ILLINOIS, an Illinois )

non-profit corporation, CATHOLIC CHARI- )

TIES OF THE DIOCESE OF PEORIA, an )

Illinois non-profit corporation, CATHOLIC )

CHARITIES OF THE DIOCESE OF JOLIET, )

INC., an Illinois non-profit corporation, and )

CATHOLIC SOCIAL SERVICES OF SO. )

ILLINOIS, DIOCESE OF BELLEVILLE, an ) Case No. 2011 MR 25

Illinois non-profit corporation, )

Plaintiffs, ) Hon. John Schmidt

vs. ) Judge Presiding

)

STATE OF ILLINOIS, LISA MADIGAN, in )

her official capacity as the Attorney General )

of the State of Illinois, ERWIN McEWEN, )

in his official capacity as Director of the Dept )

of Children & Family Services, State of Illinois, )

the DEPARTMENT OF CHILDREN & FAM- )

ILY SERVICES, State of Illinois, ROCCO J. )

CLAPS in his official capacity as Director of the)

Department of Human Rights, State of Illinois, )

and the DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS, )

State of Illinois, )

Defendants. )

and )

SUSAN TONE PIERCE, as Next Friend and on )

Behalf of a certified class of all current and )

Future foster children in custody of DCFS in )

B.H. v. McEwen, No. 88 cv 5589 (N.D.Ill. 1988); )

SARAH RIDDLE and KATHERINE )

WESEMAN, )

Intervenors. )

______________________________________________________________________________

PLAINTIFFS MOTION TO RECONSIDER, REHEAR AND VACATE

THE SUMMARY JUDGMENT ORDER OF AUGUST 18, 2011, DISMISSING

PLAINTIFFS CLAIMS AND VACATING THE PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

2 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

Plaintiffs, the Catholic Charities entities for four Roman Catholic Dioceses in Illinois

(hereinafter collectively referred to as plaintiffs, and separately as Springfield, Peoria,

Joliet, and Belleville), hereby move, respectfully, and by their undersigned attorneys,

pursuant to Section 2-1203(a) of the Illinois Code of Civil Procedure (735 ILCS 5/2-1203(a)),

that the Court reconsider, rehear, and vacate its Summary Judgment Order, entered on August

18, 2011, dismissing all of plaintiffs claims and vacating the preliminary injunction entered on

July 18, 2011, nunc pro tunc as of July 12, 2011.

In support of this motion, plaintiffs submit additional sworn Supplemental Declarations

from Steven Roach, Patricia Fox, Glenn Van Cura, and Gary Huelsmann, in addition to the

evidentiary matters including the uncontradicted allegations contained in their Verified Second

Amended & Supplemental Complaint

1

that plaintiffs previously filed. Further, they state as

follows:

1. Plaintiffs submit, with respect, that the Courts Summary Judgment Order,

entered August 18, 2011 (the Order), should be reconsidered, reheard, and vacated, and the

preliminary injunction order reinstated pendente lite, thereby preserving the status quo ante, for

the reasons elaborated below, inasmuch as the Court has misapprehended or overlooked matters

of fact adduced by the parties as well as certain controlling issues of law. Plaintiffs further

submit that, while the Court expressed its belief that all the facts were undisputed and the case

deserved to be adjudicated on a fast track basis and on cross motions for summary judgment,

there are genuine issues of material fact that came to light, especially upon the Courts granting

the ACLUs motion for leave to intervene, which introduced a host of new facts related to the

1

The State defendants did not answer any of the factual allegations of the plaintiffs Verified Second Amended &

Supplemental Complaint (Verified 2d Amd. & Suppl. Compl.), which therefore stand as admitted, together with

the uncontradicted sworn Declarations which plaintiffs also filed. The State defendants filed no counter-affidavits

nor a single sworn Declaration in support of their position or in opposition to any of plaintiffs submissions.

3 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

federal Consent Decree in the B.H. class action case which has been pending for so many years

against the defendants, Department of Children & Family Services (DCFS) and its Director,

currently defendant McEwen (discussed infra, pp. 10 et seq.).

2

Plaintiffs do not endeavor to

enforce any provision of the Consent Decree herein, nor do they contend that either the Court or

anybody but parties to that litigation (and privies) are bound by the Decree. But they adduce

relevant facts arising out of that litigation for the limited purpose of informing this Court of the

extensive factual backdrop against which the relationship between the State defendants and

plaintiffs, the DCFSs independent service contractors, must be assessed, especially with respect

to plaintiffs reasonable expectations as to the nature and duration of that relationship, and

specifically, as to their expectation that their FY2012 contracts for foster care and adoption

services would be renewed. At a minimum, these and other relevant, material facts precluded

entry of summary judgment for the defendants. Indeed, far from proving their case so decisively

as to warrant entry of summary judgment which would meet the high standard (free from

doubt) that the Code of Civil Procedure requires (735 ILCS 5/2-1005(c); Purtill v. Hess, 111

Ill.2d 229 (1986)), defendants motion did not, and could not, avoid or overcome a host of

genuine issues of material fact sufficing to bar defendants motion for summary relief. On the

contrary, the defendants contentions in support of their summary judgment motion carefully

scrutinized were fraught with doubt. The Summary Judgment Order awarded in favor of

defendants therefore cannot stand, as a matter of law, or in the light of justice.

2. We address the multiple issues of law and fact that warrant reconsideration of the

Summary Judgment Order, seriatim, as follows.

2

Plaintiffs are advised that defendant McEwen has just resigned as Director of the Department of Children &

Family Services (DCFS) for reasons they do not know, effective at some future date. Plaintiffs will substitute the

new Director as defendant when the resignation and/or the new appointment become effective.

4 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

A. Plaintiffs Had Legally Protectable Property Interests An Objective Expectancy

Which Defendants Illegally Denied In Refusing To Renew Contracts For FY 2012

3. This Court made short shrift of plaintiffs contention that each of them had a

legally protectable property interest at stake in this case, which the State defendants denied,

abruptly and illegally, when they cited plaintiffs religious beliefs as the basis for suddenly

refusing on July 8, 2011, to renew plaintiffs contracts contracts as proposed by DCFS, with

whose terms all of the plaintiffs were in complete accord for child welfare services for FY

2012. This refusal to renew evidenced by identical telefaxed letters to each of the plaintiffs

late that afternoon, just after defendants were served with notice of plaintiffs motion for

emergency injunctive relief, due for presentment before this Court on the next Tuesday

abruptly ended the parties forty year contractual relationship even though DCFS also insisted

that plaintiffs carry on in rendering services pending transitioning of their cases to new child

welfare agencies. Now defendants action, upheld by this Court, imminently threatens to put

plaintiffs entirely out of the business of providing foster care services forever (as DCFS is the

sole source for referral of new cases), and to force plaintiffs to shut down their network of foster

families, social workers, and support services across most areas of the State of Illinois.

Inevitably, the practical upshot and inevitable result of this draconian step will be to disrupt child

placements and to sunder the truly vital, tender bonds that thousands of Illinois needy children

have forged over days, weeks, months, and years with their assigned Catholic Charities

caseworkers.

4. In its Summary Judgment Order (Order), this Court said:

The issue presented is whether or not the Plaintiffs have a legally recognized

protected property interest in the renewal of [their] contracts to provide foster care and

adoption services. This analysis must begin there. If the Plaintiffs have a legally

protected property interest then this Court must employ a due process analysis concerning

5 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

the States denial of the contract renewal. If there is no legally protected property interest

the analysis ends and summary judgment for the Defendants is appropriate (Op., p. 2).

The Court went on to hold that the analysis not only begins at this point but ends there. Thus it

ruled as follows:

Plaintiffs do not have a legally recognized protected property interest in the

renewal of its contracts for foster care and adoption services. Plaintiffs are not required

by the State to perform these useful and beneficial services. There are no statutory terms

creating a property interest in Plaintiffs contracts. Thus, the Plaintiffs contract with the

State, which is renewable annually, is a desire of the Plaintiffs to perform their mission as

directed by their religious beliefs. The fact that the Plaintiffs have contracted with the

State to provide foster care and adoption services over forty years does not vest the

Plaintiffs with a property interest. Polyvend v. Puckorius, 77 Ill.2d 287 (1979). The

Plaintiffs invite this Court to extend the term legally protected property interest to those

whose state contracts are not renewed. The Court declines this invitation. Kraut v.

Rachford, 51 Ill.App.3d 206 (1

st

Dist. 1977). No citizen has a recognized legal right to

contract with the government.

In sum, the Plaintiffs have failed to show they have a legally recognized property

right to renew their contracts [footnote omitted]. The State may refuse to renew the

Plaintiffs contracts (id., pp. 2-3).

5. With respect, the Court has seriously misconceived the thrust of plaintiffs

contentions. Plaintiffs have never contended that they, or any other party, has any legal right to

contract with the government (supra), let alone to have such a contract judicially dictated or

coerced. On the contrary, plaintiffs are contending that, under the particular and peculiar

circumstances such as exist in this case, a veteran, longstanding State contractor providing

continuous, ongoing services for the benefit of patients or, as in this case, continuous and

ongoing services for needy and vulnerable children and families, which agreed to each and every

contract term as drawn up and proposed for renewal by defendants, cannot thereafter be

suddenly terminated, that is, declared ineligible for any renewal of its contract, for reasons that

are contrary to law in this case, undeniably in retaliation for plaintiffs assertion of a

conscientious, religion-based objection to processing applications by civil union couples. This

was a lawless act, epitomizing arbitrary and capricious government action, devoid of any

6 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

justification in Illinois substantive law and also grossly unfair as a matter of process. Here, the

government cast a blind eye at the relevant, operative provisions of the very laws the Illinois

Religious Freedom Protection and Civil Union Act and the Illinois Human Rights Act which

its officials purported to invoke, provisions which do not apply to plaintiffs or bind them but

which quite the contrary explicitly exempt them!

6. One of the pair of cases cited by the Court in its Summary Judgment Order (Op.,

p. 2), Polyvend, Inc. v. Puckorius, 77 Ill.2d 287, 295-96 (1979), suggests a helpful analogy to

employment cases. In that context, defendants would have this Court view plaintiffs as if they

were mere employees at will, once their annual employment contracts expired as of June 30,

2011, even though defendants kept them at work extending de facto the same contract terms

through July 8

th

when defendant McEwen of DCFS faxed the non-renewal letters. For such at

will employees, it is hornbook law that they may be fired for a good reason, a bad reason, or no

reason at all. But it is likewise hornbook law that employees at will cannot be fired for an

illegal reason! Similarly, nobody applying for employment can lawfully force an employer to

hire him or her. But an employer may not refuse to hire somebody for a discriminatory

reason as, for example, on account of his or her religion! Here, apart from the evidence

plaintiffs have adduced which proves or at least raises genuine issues of material fact that

under all the relevant circumstances plaintiffs enjoyed an objective expectancy and de facto

tenured status as one of the contracted social welfare agencies providing foster care and adoption

services for the Department of Children & Family Services (DCFS), plaintiffs also have adduced

compelling evidence far more than the minimum needed to raise a genuine fact issue barring

summary judgment that DCFSs refusal to renew their foster care and adoption contracts was

based solely on plaintiffs conscientious religious objections. That alone should be dispositive in

7 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

plaintiffs favor. Plaintiffs legal contentions, as urged in Counts I, II, and III, demonstrated that

they were in full compliance with Illinois law and fully protected in urging those conscientious

religious objections. Therefore, there can be no doubt, upon the present record, that but for

plaintiffs Roman Catholic beliefs, DCFS would have countersigned their contracts, whose terms

were precisely the same terms that DCFS had demanded, to which plaintiffs fully agreed. At a

minimum, summary judgment was barred. And plaintiffs reassert, with all deference, that they

should have been awarded summary judgment.

3

7. The second case cited by this Court in its Summary Judgment Order (Op., p. 3),

Kraut v. Rachford, 51 Ill.App.3d 206, 213-14 (1

st

Dist. 1977), also supports plaintiffs. Indeed, we

cited Kraut at p. 39 of our memorandum in support of our cross motion of summary judgment.

In that case, the Appellate Court held that plaintiff was held to have had an objective

expectancy in his continuation at [Homewood-Flossmoor High School] on a tuition-free basis,

sufficient to warrant due process protection of that interest, even though plaintiffs statutory

rights afforded him an interest only in attending a high school, not any particular high school,

given the particular circumstances in that case, where Homewood-Flossmoor had fostered the

plaintiffs objective expectancy by allowing him to attend on a tuition-free basis during his

freshman year and further allowing him to proceed to final registration for his sophomore year,

etc., citing, inter alia, Perry v. Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593 (1972), to which the Appellate Court

in Kraut attributed the proposition that the term property is broad enough to offer protection to

an objective expectancy of the continuance of an interest which has been initially conferred by

the state (51 Ill.App.3d at 212).

3

It bears repeating that the State defendants never answered the verified allegations of plaintiffs Second Amended

& Supplemental Complaint (Verified 2d Amd. & Suppl. Compl.) before this Court granted them summary

judgment. Factual allegations therein are therefore deemed admitted, and plaintiffs are also entitled to all reasonable

inferences that may be drawn from those allegations.

8 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

8. Here, as the trial court had held in Perry, supra, this Court also has held that the

lack of a contractual or tenure right to re-employment [akin to contract renewal in this case],

taken alone, defeats [plaintiffs] claim that the nonrenewal of [their] contract violated their legal

rights. The Supreme Court explicitly rejected this view, holding that plaintiff in that case, a non-

tenured college professor, should have the right to show that the decision not to renew his

contract was, in fact, made in retaliation for his exercise of the constitutional right to free

speech (408 U.S. at 596-598).

9. The DCFSs decision not to renew plaintiffs child welfare agency service

contracts for foster care and adoption services for FY2012 was indisputably made on the basis of

plaintiffs religious beliefs, specifically their beliefs as an element of their Roman Catholic Faith

that cohabitation outside of marriage is morally wrong. Thus this case is much stronger than the

case of the college professor in Perry. Further, even absent contractual tenure rights, A

persons interest in a benefit is a property interest for due process purposes if there are such

rules or mutually explicit understandings that support his claim of entitlement to the benefit and

that he may invoke at a hearing, and that the professor must be given an opportunity to prove

the legitimacy of his claim of such entitlement in light of the policies and practices of the

institution, whether written or unwritten (id. at 602-03).

10. In this case, a whole medley of factors have fostered and buttressed plaintiffs

objective expectancy and explicit understandings that their contracts would be renewed.

These factors fully deserve to be explored and weighed among all the circumstances of the case,

even absent plaintiffs showing they possessed an explicit right to automatic renewal of their

contracts for performance of services as an Illinois child welfare agency performing foster care

and adoption services.

9 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

11. First, the facts in this case are much closer to those before the court in Bio-

Medical Laboratories, Inc. v. Trainor, 68 Ill.2d 540, 547 (1977), than to those in Polyvend, Inc.

v. Puckorius, 77 Ill.2d 287 (1979), which was decided two years after Bio-Medical, and yet this

Court cited Polyvend in its Summary Judgment Order (Op., p. 2). In Bio-Medical, a physician

had been providing professional medical services for his patients under Medicaid in an ongoing,

continuous program over a period of approximately eight years, not requiring annual bids (id.),

whereas in Polyvend, in the words of our Supreme Court, there was simply an annual invitation

to bid and a resulting annual award of the license plate contract, without the award of such

contracts in any given year giving rise to any right or interest in future State contracts, as the

individual contracts were entirely independent matters (Polyvend, supra, 77 Ill.2d at 298). By

contrast, in this case as in Bio-Medical, the plaintiffs render continuous, ongoing professional

and related services for the benefit of vulnerable, needy children and their families, which

services are not bounded by any finite number nor even for any durational term as plaintiffs

typically have been given new annual contracts to review and sign well after expiration of their

predecessor contracts. This is not even remotely comparable to the mere performance, as in

Polyvend, of wholly discrete, discontinuous, and mutually independent annually bid

undertakings to manufacture, metal-stamp, and produce a finite quota of State license plates.

Professional care for children and the manufacture of chattels are light years apart.

Second, plaintiffs are professionally licensed by the State, based inter alia on their

performance. As demonstrated before this Court, the plaintiffs outstanding performance has led

defendant, Department of Children & Family Services (DCFS), to license them for years into the

future. As the Illinois Supreme Court queried in Balmoral Racing Club, Inc. v. Illinois Racing

Board, 151 Ill.2d 367, 405-06 (1992), what purpose is served by having a racing license (in

10 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

Balmoral it was a license to conduct thoroughbred races) if the State does not grant racing dates

on which that license may be profitably exercised, and absent which Balmorals interest in

retaining an occupation would be thwarted? Here, too, as the State of Illinois has a monopoly

on referrals for foster care, the defendants sudden refusal to renew plaintiffs annual contract for

FY2012 amounts to a de facto cancellation of plaintiffs licenses to provide foster care services.

Yet, the Seventh Circuit has held that a child welfare agency has a property interest in the

renewal of its license clothed with due process protections (Easter House v. Felder, 910 F.2d

1386, 1395 (1990)).

Third, the relevant facts surrounding the new FY2012 contracts show that the parties

fully agreed to each and every contract term that defendants had proposed to plaintiffs. Indeed,

plaintiffs had signed the contracts as proposed in haec verba by DCFS. That DCFS refused to

countersign them when plaintiffs signed and returned the FY2012 contracts, but DCFS never

proposed any contractual terms other than those that plaintiffs agreed to. DCFSs only

disagreement was on a legal issue over the interpretation of the contractual terms its own

officials had drafted terms that simply committed the plaintiffs to comply with Illinois law (see

generally, Pls. Memo in Spt. of Mot. for Summ. Judgmt., pp. 17-18 & Declns. and Verified 2d

Am. & Suppl. Compl. and references cited therein). Thus the indisputable truth is that the

parties were in complete agreement over the terms of the FY2012 contracts. Therefore, plaintiffs

urge that defendants are bound by those terms, subject to this Courts adjudication which

plaintiffs have sought by way of Declaratory Judgment as to the purely legal issue pending

before this Court, upon Counts I and II of plaintiffs verified 2d amended & supplemental

complaint. That is the real question on which this case should pivot, and it is twofold: Does

compliance with Illinois law require, upon a proper reading of the Illinois Human Rights Acts

11 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

place of public accommodation provisions and the Illinois Religious Freedom Protection and

Civil Union Acts provision purporting to exempt religious practice on the part of religious

bodies such as plaintiffs, that plaintiffs conscientious objection be rejected, as defendants insist?

Clearly, given what was undeniably a meeting of the minds as between plaintiffs and DCFS as to

each and every contract term that DCFS proposed for FY2012, isnt it obvious that plaintiffs

at a minimum had an objective expectancy of a property interest in their continuing rendition

of professional services into FY2012?

Finally, and cardinally, the entire thrust of Illinois reformed child welfare system, of

which plaintiffs have been an integral participant over recent decades, is that Illinois neglected,

abused, and otherwise dependent children should receive at least minimally adequate care, as

mandated by the Restated Consent Decree in the federal proceeding entitled, B.H. v. McEwen,

No. 88 C 5589 (N.D. Ill.). See, generally, Pls. Memo in Opp. to Intervenors Mot. to Dismiss 2d

Am. Compl., etc., pp. 25-34. In short, and as detailed at length in our cited memorandum

opposing the ACLUs motion to dismiss, the B.H. Decree imposed on DCFS (by agreement of

DCFS, as memorialized in the Consent Decree) an array of obligations intended to serve the best

interest of children in foster care. See, generally, Pls. Memo in Opp. to Intervenors Mot. to

Dismiss 2d Am. Compl., etc., Parts IV, V & VI, pp. 18-42 passim. Review of those obligations

(id., especially pp. 25-34) leaves no doubt that forcing plaintiffs as DCFS now purports to do

to abandon their foster care and adoption mission would undermine the objectives of the Decree

and cause incalculable and permanent harm to children in foster care in Illinois. Both in the B.H.

litigation and in independent studies it has been amply proven that the two most critical factors in

successful child placements in foster care and eventual permanency (either reunification with the

childs family or, failing that objective, adoption) are stability in placement and continuity of

12 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

services (id., p. 29 et seq.). Therefore, plaintiffs could hardly anticipate indeed, they expected

the contrary! that their past practice of referring applications of unmarried cohabiting couples

for foster care or adoption to DCFS for handling by other social service agencies, would

suddenly be deemed upon an palpably erroneous reading of the applicable Illinois law to be

grounds for DCFSs summarily ending plaintiffs services, especially given plaintiffs high

performance ratings based on DCFSs most critical performance criteria (i.e, stability and

continuity, supra). The most important factor of all those bearing on plaintiffs objective

expectancy as to their tenure is a Supplemental Order to Enforce Consent Decree, entered in the

B.H. litigation by U.S. District Judge John F. Grady, on June 30, 2009, a signed copy of which is

appended hereto.

4

That Supplemental Order, of which plaintiffs were notified by explicit court

order, provided inter alia that DCFS, as defendant in that litigation:

shall not proceed with any reduction or cancellation of any programs or services

(including without limitation foster parent and relative reimbursement payments,

adoption subsidies, contracts for placements, comprehensive assessments to identify

medical and mental health needs upon entering care, medical care, psychiatric

services, counseling services, daycare services, System of Care services, services for

pregnant and parenting teens, respite services for foster parents, performance of

background checks, and fingerprinting, etc.) (emphasis supplied).

4

This document is one among a host of documents in the voluminous record of those federal proceedings, which the

intervenors brought to this Courts attention upon their being allowed to intervene in this case. Plaintiffs had to

retrieve relevant documents in the federal proceedings under tight time constraints imposed by this Courts fast

track schedule for filing and hearing of the cross motions for summary judgment from the Federal Archives

depository at a remote location on Chicagos southwest side, where limited copying facilities are available. Those

Archives are laden with numerous other documents bearing on DCFSs legal relations with its contractors, such as

plaintiffs, and plaintiffs have not been able to review all of them, much less copy them in time for filing herein.

Again, this is not to enforce that Consent Decree but rather to spread of record in this case, posing state law issues,

as many of the relevant circumstances forming the backdrop to the parties relations as possible.

13 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

shall maintain current caseload ratios for investigative personnel, follow-up

caseworkers, and supervisory staff, whether provided by DCFS or its contracted

agencies (emphasis supplied); and

shall publish this Order by posting it on its website, by transmission to foster

parents and to contractors and providers of services, etc. (emphasis supplied).

As set forth in plaintiffs Supplemental Declarations, submitted herewith, plaintiffs were notified

of this Supplemental Order, which they understood to reinforce their objective expectancy by

binding DCFS to maintain their tenure, absent further Order of the U.S. District Court. While the

B.H. Consent Decree provides that it is not enforceable outside that federal litigation, plaintiffs

having been served with court-ordered notice of this Supplemental Order were surely entitled

to rely on its contents in continuing to entertain their objective expectation that DCFS had

agreed to the Restated Consent Decree, pursuant to the terms of which it had been ordered not

to terminate their contracts, lest the paramount goals of stability, continuity, and permanency

for the sake of the children in Illinois child welfare system would be severely disserved.

B. Plaintiffs Had Legally Protectable Liberty Interests That DCFS Violated By Its

Abrupt, Legally Baseless Refusal To Renew Plaintiffs FY2012 Contracts

12. This Court expressed its belief during oral argument on the parties cross motions

for summary judgment that no liberty interests were at stake in this case as nobody was in danger

of going to jail. But in Bd. of Regents v. Roth, supra, 408 U.S. at 472, the U.S. Supreme Court

said that a persons protected liberty interests have far broader scope than freedom from bodily

restraint:

While this Court has not attempted to define with exactness the liberty guaranteed

[by the Fourteenth Amendment], the term has received much consideration and some of

the included things have been definitely stated. Without doubt, it denotes not merely

freedom from bodily restraint but also the right of the individual to contract, to engage in

any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a

14 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own

conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized as essential to the

orderly pursuit of happiness by free men. Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399. In a

Constitution for a free people there can be no doubt that the meaning of liberty must be

broad indeed. See, e.g., Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 499-500; Stanley v. Illinois,

405 U.S. 645.

13. Moreover, the Court in Bd. of Regents addressed the matter of negative impacts

on a persons good name and reputation, which might damage his standing and associations in

his community For where a persons good name, reputation, honor, or integrity is at stake

because of what the government is doing to him, notice and an opportunity to be heard are

essential, citing Wisconsin v. Constantineau, 400 U.S. 433, 437; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344

U.S. 183, 191; Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123; United States

v. Lovett, 328 U.S. 303, 316-17; Peters v. Hobby, 349 U.S. 331, 352 (Douglas, J. concurring).

The Court opined, albeit in dicta, that [i]n such a case, due process would accord an opportunity

to refute the charge before officials (Bd. of Regents, 408 U.S. at 573).

14. That plaintiffs vital liberty interests were at stake in this case, therefore, cannot

be doubted. Contrary to this Courts Summary Judgment Order, proof of a legally recognized

property right to renew their contracts (Op., p. 3) was not a sine qua non, nor an indispensable

prerequisite for plaintiffs prevailing in this case. Not only did plaintiffs have an objective

expectancy in renewal of their FY2012 contracts, but they also had multiple legally protectable

liberty interests that defendants infringed. Their contracts were terminated, as they were

declared ineligible, having forfeited not only the FY2012 contracts but also their right to

contract and to carry on their non-profit business of providing foster care and related adoption

services. DCFS now proclaims to the world, that the plaintiffs stand condemned albeit without

having had any day in court as law breakers, stigmatized and besmirched in the public eye as

perpetrators of alleged illegal discrimination. Casting such aspersions on those who assert

15 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

conscientious religious objections in good faith is an affront to plaintiffs constitutional and

statutory rights under Article I, Section 3 of the Illinois Constitution of 1970 and the Illinois

Religious Freedom Restoration Act, as detailed in Count III of their Verified 2d Amended &

Supplemental Complaint. Those constitutional and statutory provisions are also founts of Illinois

law that buttress plaintiffs objective expectancy that their contractual tenure would not be so

suddenly and arbitrarily ended because of their religious convictions. Plaintiffs are entitled to

have the opportunity to clear their good name in a court of law, to prove that it is the State

defendants who will not abide by Illinois law, which is the reason why plaintiffs brought this

lawsuit, to secure a definitive ruling pursuant to the Declaratory Judgment statute as to what

Illinois law actually provides. So, they urge anew that the Court rule on the merits of their case.

C. The Court Should Adjudicate Counts I and II of the Verified Second Amended &

Supplemental Complaint, Rejecting Defendants Misinterpretation Of Both The

Illinois Human Rights Act And Religious Freedom Protection And Civil Union Act

15. In footnote 1 to its Summary Judgment Order (Op., p. 3 fn. 1), this Court ruled:

As the court has found the Plaintiffs have no protected property right in the

renewal of their contracts it is not necessary to address their claims the State violated

their rights pursuant [to] the Illinois Human Rights Act, 775 ILCS 5/1-101 et seq., the

Illinois Religious Freedom Protection & Civil Union Act, 750 ILCS 75/1 et seq. and the

Illinois Religious Freedom Restoration Act 775 ILCS 35/1 et seq.

Respectfully, but ardently, plaintiffs disagree. In Counts I and II of their latest amended

complaint, plaintiffs asked this Court to resolve a pair of actual controversies over two key issues

of statutory interpretation. Whether or not plaintiffs prevail in enjoining or overturning

defendant DCFSs decision not to renew their FY2012 service contracts for foster care and

adoption services, they remain aggrieved by: (a) the Attorney Generals pursuit of a statewide

investigation based on a gross misreading of the Human Rights Acts pattern and practice and

place of public accommodation provisions; and (2) DCFSs branding them as lawbreakers

16 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

guilty of discrimination against civil union couples in violation of the Illinois Religious Freedom

Protection and Civil Union Act, and thereby ineligible for further contracts with the State of

Illinois. Also, plaintiffs remain exposed and vulnerable to the Illinois Department of Human

Rights entertaining still more individual charges of marital status and/or sexual orientation bias

against them, pursuant to the same inapt places of public accommodation provisions of the

Illinois Human Rights Act, especially given this Courts dismissal of their complaint.

16. There remains an imminent threat that plaintiffs will suffer adverse effects, which

may be dispelled by this Courts proceeding to adjudicate the claims fairly presented in Counts

I and II that would obviate that threat and permit plaintiffs to secure a proper interpretation of

these two laws, whose violation they now stand accused of, while bereft of any available or

efficacious remedy, apart from resort to this Court for reconsideration, and if need be, an appeal.

Compare, e.g., Morr-Fitz v. Blagojevich, 231 Ill.2d 474, 488-89 (2008)(the mere existence of a

claim, assertion or challenge to plaintiffs legal interests which casts doubt, insecurity, and

uncertainty upon plaintiffs rights or status, damages plaintiffs pecuniary or material interests

and establishes a condition of justiciability, etc.). Nor can the Courts dismissal of Count I be

reconciled with the Illinois Supreme Courts decision in Bd. of Trustees of So. Ill. Univ. v. Dept

of Human Rights, 159 Ill.2d 206, 211 (1994), which expounded on the proper approach to

interpreting the place of public accommodations provisions of our Human Rights Act and

issued a writ of prohibition to cease an investigation into possible violation of that Act, which

was proved outside the scope of the statutory authorization for the Department of Human Rights.

Here, plaintiffs have demonstrated that the Attorney Generals statutorily-based statewide

investigation of the plaintiffs pursuant to the pattern or practice provisions of the Human

Rights Act are equally unauthorized by the statutory provisions in that Act. At a minimum, a

17 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

Declaratory Judgment should issue to that effect, which would apply to both the Attorney

Generals Office and the Illinois Department of Human Rights.

D. The Court Should Also Address And Rule On Plaintiffs Claim In Count III,

Charging A Violation Of The Illinois Religious Freedom Restoration Act

17. In the Courts Summary Judgment Order, footnote 1 (Op., p. 3), it also stated that

plaintiffs claims in Count III, pursuant to the Illinois Religious Freedom Restoration Act, 775

ILCS 35/1 et seq., need not be addressed owing to plaintiffs failure to prove they owned a

legally protected property right to renewal of their FY 2012 contracts. Again, plaintiffs

respectfully disagree. Count III is a freestanding claim, wholly independent apart from a

partial overlap of factual allegations of plaintiffs right to relief vel non upon any other count.

As the Supreme Court recognized, [T]he Religious Freedom [Restoration] Act expressly

confer[s] a right to file a judicial action when the rights protected therein are infringed upon.

Morr-Fitz, Inc. v. Blagojevich, 231 Ill.2d 464, 502 (2008), citing 775 ILCS 35/20, Judicial

Relief, which prescribes without limitation that whenever, as here, a persons exercise of

religion has been burdened in violation of [the] Act, that person may assert that violation as a

claim or defense in a judicial proceeding and may obtain appropriate relief against a

government. In its Summary Judgment Order, this Court has found already that defendants

forced plaintiffs out of foster care and related adoption services because the Plaintiff[s] would

not provide those services to unmarried cohabiting couples (Op., p. 2). Count III is neither

toothless nor merely piggybacked onto another count. It must stand or fall on its own, regardless

whether this Court finds plaintiffs had a legally protectable objective expectancy of any

property interest or right, or not, or whether they possessed a legally protected liberty interest or

right, or not.

18 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

18. Plaintiffs have alleged in their verified Count III and argued both at length and

repeatedly that they have proven each of the elements entitling them to judicial relief against

defendants herein, as government has substantially burdened their exercise of religion as those

phrases are specifically defined in IRFRA, and defendants cannot meet their resulting burden of

proof that the (a) application of the burden to plaintiffs is in furtherance of a compelling

governmental interest, and (b) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling interest.

775 ILCS 35/15; see generally, Pls. Verified 2d Amd. & Suppl. Compl., Ct. III; Memo in Spt. of

Pls. Mot. Summ. Jdgmt., pp. 28-37; Pls. Memo in Opp. to Intervnrs. Mot. To Dismiss, etc., pp.

43-54; Pls. Memo in Opp. to Defs. Cross Mot. for Summ. Jdgmt., pp. 16-17.

19. For the present, plaintiffs note that the Courts Summary Judgment Order

included a finding that, Plaintiffs are not required by the State to perform these useful and

beneficial services (Op., p. 2). If this reflects the Courts concurrence with intervenors

contention that Diggs v. Snyder, 333 Ill.App.3d 189, 195 (5

th

Dist. 2002), quoting Stefanow v.

McFadden, 103 F.3d 1466, 1471 (9

th

Cir. 1996), requires that an IRFRA plaintiff demonstrate

that the government action prevents him from engaging in conduct or having a religious

experience that his faith mandates (emph. supplied), plaintiffs point out again that the Diggs

court did not reach the construction nor address the impact of the unambiguous definition of

exercise of religion in the Act itself, as an act or refusal to act that is substantially motivated

by religious belief, whether or not the religious exercise is compulsory or central to a larger

system of religious belief, 775 ILCS 35/5 (emph. added). The Diggs court dealt with the

specific context of standards for control of prison publications, and the court sought guidance

from the 9

th

Circuits Stefanow decision, which also dealt with prison publications. The

Stefanow applied an older version of the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, in effect in

19 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

1996, which did not include the specific, broader definition of exercise of religion contained in

IRFRA. Instead, plaintiffs previously cited numerous federal cases interpreting the federal

Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), enacted in 2000, an Act which

includes a definition of exercise of religion similar to that of IRFRA (see, citations to Pls.

Memos, supra).

IRFRAs statutory definition of inter alia the textual term exercise of religion was

neither quoted nor even cited in Diggs, supra, and it clearly controls. And there is no dispute

that plaintiffs ministry is substantially motivated by their religious beliefs (e.g., Verified 2d

Amd. & Suppl. Compl., 39, pp. 31-35, uncontradicted). Moreover, other language in Diggs

describes as the hallmark of a substantial burden on ones exercise of religion as the

presentation of a coercive choice of either abandoning ones religious convictions or [not]

complying with the government regulation (333 Ill.App.3d at 195) an apt description of what

occurred in this case.

Even if this Court finds Diggs is persuasive authority here, it is not controlling, as other

Illinois courts have taken a broader reading of Illinois RFRA, not adopting the mandates

language from Diggs but rather keeping faith with the statutory definition. Thus the First District

Appellate Court in City of Chicago Heights v. Living Word Outreach Full Gospel Church &

Ministries, 302 Ill.App.3d 564, 571 (1

st

Dist. 1998), found that a church seeking a special use

permit to locate in commercial zone met the substantial burden test under IRFRA, although the

case was reversed on other grounds (196 Ill.2d 1 (2001)). See also, Justice Turners dissenting

opinion in the Fourth Districts decision in Morr-Fitz, Inc. v. Blagojevich, 371 Ill.App.3d 1175,

1187 (4

th

Dist. 2007), where he said: A forced choice between violating ones religious beliefs

and complying with the law can amount to a substantial burden within the meaning of the

20 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

Religious Freedom Restoration Act. In this case, plaintiffs claim the Rule, along with the

Governors edicts, has placed substantial government pressure on them to modify or violate their

religious beliefs or face the threat of government sanction. The alleged disregard here by the

States Chief Executive of the fundamental constitutional rights of these Illinois citizens to the

free exercise of their religious beliefs is sufficient to grant them standing under [IRFRA]

(internal citations omitted). The Fourth District was reversed by the Supreme Court, Morr-Fitz,

etc., 231 Ill.2d 474, 502 (2008). See further, Morr-Fitz v. Blagojevich, Sangamon Co., No.

2005-CH-495, Order, April 5, 2011, pp. 2-3, 5 (citing Diggs on remand in support of a finding of

substantial burden, despite lack of any finding that the pharmacist plaintiffs religious faith

mandated their practice of pharmacy). The Sangamon County Trial Court in No. 2005-CH-495

also found on remand that: The candid testimony of Secretary Adams as a whole showed the

present Rule was drafted with the Plaintiffs in mind. Secretary Adams acknowledged he was

unaware of refusals to sell emergency contraceptives for any reason other than religion. He

further testified that he did not believe that religious views should determine whether a pharmacy

dispenses a particular drug (emphasis in original). A copy of the Trial Court opinion in Morr-

Fitz, unpublished, is appended hereto.

20. Thus under plaintiffs IRFRA claim, in Count III, the burden should have shifted

to the defendants, and as we have extensively argued, defendants could not meet that burden as

the constraints in both the Human Rights Act and the Religious Freedom Protection and Civil

Union Act are not even binding on plaintiffs, let alone serving any compelling government

interest. Plaintiffs also have extensively refuted intervenors asserted compelling interests by

demonstrating (a) that the States interest in accumulating the largest pool of potential foster

parents possible would be subverted, not advanced, by forcing plaintiffs to cease operations (Pl.

21 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

Memo in Opp. to Intrvnrs. Mot. to Dismiss, pp. 51-54, & Declarations cited therein); and (b)

that the States goal of preventing discrimination is inapt where sectarian adoption agencies

such as plaintiffs are explicitly exempted from the Human Rights Act bans that apply to places of

public accommodation and also where Illinois courts repeatedly have held that a legal distinction

based on cohabitation does not violate state or federal equal protection principles (id., pp. 52-54).

Finally, as for the IRFRAs least restrictive alternative test, neither the defendants nor

intervenors have said a word about the federal mandate, Executive Order 13559, validating use

of referral procedures by child welfare agencies (Verified 2d Amd. & Suppl. Compl., 47, pp.

40-41, unanswered). Plaintiffs have used such referral procedures for forty years, without

challenge. And as plaintiffs Supplemental Declarations now show, their use is uncommon,

given that no civil union couple has been known to apply to plaintiffs since the effective date of

the Religious Freedom Protection and Civil Union Act on June 1, 2011. See, Supplemental

Declarations submitted herewith.

E. The Court Should Reconsider Its Dismissal Of Count IV Charging Violations Of

Plaintiffs Rights To Substantive And Procedural Due Process Of Law

21. The Court focused its Summary Judgment Order exclusively on plaintiffs due

process claims, limited to the question whether they had a legally protectable property interest or

property right (Op., pp. 1-3). The rejection of these claims also is deserving of reconsideration,

especially given the points we have already asserted herein (supra, 3-14, pp. 3-13), especially

that plaintiffs had a legally protected liberty interest at stake as well as an objective expectancy

in property, namely, the FY2012 contracts as proposed by defendant DCFS, signed by plaintiffs,

and then rejected by defendant explicitly and exclusively on the basis of plaintiffs religious

objections.

22 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

F. The Court Should Reconsider Its Vacation Of The Preliminary Injunction,

Protecting The Status Quo Ante In The Best Interest Of Illinois Children

22. The Supplemental Declarations submitted herewith amply detail the devastating

economic impact that the Courts Summary Judgment Order will have on all four plaintiffs, if

not reconsidered and vacated. But what is of paramount concern here is that the anticipated

indeed, inevitable -- impact on Illinois child welfare system will be calamitous. We have

detailed the pertinent facts in Part V of Plaintiffs Memorandum of Law in Opposition to

Intervenors Motion to Dismiss their Second Amended Complaint, or in the Alternative, for

Summary Judgment, filed just two days before the Courts hearing on cross motions for

summary judgment, that is, on Monday, August 15, 2011, under the heading, The Relief Sought

By The Intervenors Would Cause Incalculable Harm To Children In Foster Care In Illinois, pp.

25-34. In that section of their memorandum, plaintiffs canvassed the key components of the

Restated Consent Decree in the B.H. v. McEwen federal litigation, which bound DCFS to make

profound and lasting reforms in the child welfare system, with a view based on the parties and

the federal Judges review of reports from a panel of experts toward revamping and revitalizing

what had degenerated into a seriously flawed system. Plaintiffs thereupon proceeded to

demonstrate how this sudden transitioning of some 2,200 children who have been placed in

foster homes through plaintiffs agencies, which defendants urged and which this Courts

Summary Judgment Order now would require, absent a stay and reinstatement of the Courts

preliminary injunction, would inevitably cause a change in caseworkers assigned to children,

would destabilize placements, would lose the benefit of many foster parents who would cease

working with foster children if Catholic Charities were barred from the child welfare system, and

would harm recruiting efforts, which have proved so successful through Catholic Churches

across Illinois. U.S. District Judge Grady, presiding over the case apparently from its inception,

23 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

observed in an early opinion, B.H. v. Johnson, 751 F.Supp. 1387, 1395 (N.D. Ill. 1989), that

[c]hildren are by their nature in a developmental phase of their lives and their exposure to

traumatic experiences can have an indelible effect upon their emotional and psychological

development . Plaintiffs will detail more particulars in this regard in their Motion for Stay,

which they will file shortly. In the meantime, plaintiffs urge, with respect, that the Court

reconsider, rehear, and vacate its Summary Judgment Order, and that pending its consideration

of plaintiffs instant motion, it assure that the status quo ante continues in effect, as before the

Summary Judgment Order was handed down on August 18, 2011.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray that the Court reconsider, rehear, and vacate its Summary

Judgment Order, and that pendente lite it assure that the automatic stay of its final judgment

encompass a continuation of its earlier preliminary injunction order, pendente lite, so as to assure

that the status quo ante remains in effect; and that the plaintiffs have all other relief to which

they may be entitled upon the premises in accordance with law.

Respectfully submitted,

Of Counsel: ____________________________________

Thomas Brejcha One of the Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Peter Breen

Thomas More Society,

A public interest law firm

29 So. LaSalle St., Suite 440

Chicago, IL 60603

Tel. 312-782-1680

Fax 312-782-1887

Attorneys for all Plaintiffs

Bradley E. Huff

Richard Wilderson

Graham & Graham, Ltd.

1201 South Eighth Street

Springfield, IL 62703

Tel. 217-523-4569

24 of 24 Case No. 2011 MR 254

Fax 217-523-4656

Attorneys for Catholic Charities for

the Diocese of Springfield in Illinois

Patricia Gibson

Chancellor & Diocesan Counsel

Diocese of Peoria

Spalding Pastoral Center

419 NE Madison Avenue

Peoria, IL 61603

Tel. 309-671-1550

Fax 309-671-1576

Attorney for Catholic Charities

for the Diocese of Peoria

James C. Byrne

Spesia & Ayers

1415 Black Road

Joliet, IL 60435

Tel. 815-726-4311

Fax 815-726-6828

Attorney for Catholic Charities

for the Diocese of Joliet, Inc.

David Wells

Catherine A. Schroeder

Thompson Coburn LLP

One US Bank Plaza

St. Louis, MO 63101-1611

Tel. 314-552-7500

Fax 314-552-7000

Attorneys for Catholic Social

Services for Southern Illinois,

Diocese of Belleville

B4/B5/2B11 13:B6

217

CIRCUIT

PAGE B2/08

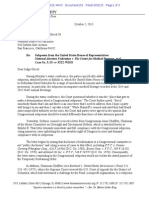

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE SEVENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT

SANGAMON COUNTY, ILLINOIS

MORR-FlTZ, INC., an Illinois corporation, )

DIBIA FITZGERALD PHARMACY, )

Licensed and Practicing in the State of Illi.nois )

as a Phannacy; L. DOYLE, INC., an Illinois corporation)

D/B/A EGGELSTON PHARMACY, )

Licensed and Practicing in the State of Illinois )

as a Phannacy; KOSIROG PHARMACY, INC" )

an. Illinois corporation D/BIA KOSIROO REXALL )

PHARMACY, Licensed and Practicing )

in. the State of Illinois as a Phannacy; LUKE )

VANDERBLEE.K; and GLENN KOSIROG, )

Plaintiffs, )

v. )

)

ROD BLAGOJEVICH, Governor, State )

of Illinois; FERNANDO GRILLO, Secretary, )

Illinois Department of Financial and. Professional )

RegulaHon; DANIEL E. BLUTHARDT, Acting Director)

Division of Professional Regulation; and the )

STATE BOARD OF PHARMACY )

Defendants. )

FILED

APR 05 201\ CIV.-6

Clertc of tho

ClTcult Court

Case No. 2005-CH-000495

ORDER GMNT.ING AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

The Plaintiffs are two phannaci.sts and the tbree oorporatiou$ through' whicb they 0W11

and operate their phanna.cies. Plaintiffs' claim. they are problbited by their religion and

consciences from participating in the sale of drugs called Clemergency contraceptives." Plaintiffs

challenge 68 ILL. ADMIN. CODE 1330.500(e)-(h) ("the Rule") which requires them to participate

in sales of drugs called emergency contraceptives. Under an agreell),ent between the parties,

Count III and Count V were voluntarily dismissed OD, Plaintiffs' motion prior to trial.

Additionally, the court is granting Plaintiffs Motion to Voluntarily Dismiss Count n without

prejudice. Finally, all Plaintiffs' with respect to administra.tive rules no longer in effect

have been dismissed with prejudice. On March 10, 2011, this Court held a bench trial on .

Plaintiffs' claims that the Rule is invalid under the Healthcare Right of Conscience Act, 745

1

APR-05-2011 14:32

217

98%

P.02

84/85/2011 13:05

217

CIRCUIT

PAGE 83/88

ILCS 70/1 et seq. (the "Conscience Act"), the Religious Freedom Restoratiop Act, 735 ILCS

35/1 et seq. ("RPRA"), and the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The

Court is familiar with the parties and their argmnents, as this suit has been pending for nearly six

years. After consideration ofthe eVidence, the Court finds as follows:

Based upon the testimony of the Plaintiffs, Luke Vander Bleek and Glenn Kosirog, ,who

are the owners of the phannacies in question, the Court finds Plaintiffs have sincere religious and

oonscience-based o1{jcctions to participating in any way in' the distribution of emergency

contraceptives. The Plaintiffs testified that the Rule chills their religious exercise by forcing them

to choose between violatj.ng their religion and violating the law. Their pharmacies have written

ethical guidelin.es prohibiting participation in distribution of these drugs. The evidel),Ce was olea.r.

from. the trial that the objections of these Plaintiffs and their closely held corporation are

essentially Oll,e and the same. The OW11ers olearly set the policy atld tightly control the day to day

operations of their pharmacies. The Rule also imposes financial harms by making it m.ore

difficult for Plaintiffg to recruit employees (causing one Plaintiff pharmacy to olose) and pIau

their businesses. The Plaintiffs have produced sufficient evidence to show the Rule has imposed

a financial hardship on their businesses.

The current Rule is the fourth version of a policy initiated in April 2005. At the outset,

Governor announced the rule's purpose: to stop religion from "stand[ing] in the

way!! of dispensing drugs, and force phannacies to "fill prescriptions without making moral

judgments." See Statement (Apr. 13, 2005) (Ex. J). Secretary of the Illinois Department of

Financial and Professional Regulation C'IDFPR") Fernando Grillo announced that the Rule

would make sure the drugstore counter ',,""ill not become a. place to debate" reHgiolls beliefs, and

that it is not the responsibility of the State of Illinois to a.ccommodate those beLiefs." See Letter

2

APR-05-2011 14:32

217

98Y.

P.03

04/05/2011 13:06

217

CIRCUIT

PAGE 04/08

to Chicago Tribune (Apr. 16) 2005) (Ex. H) C'We are telling pharma.cies ... they can't let an

in.dividual pharmacist's beliefs" interfere With selling contraceptives). Even in 2008) the

Governor's Office ackl10wledged that the role was issued "because of the conscience concerns of

SOl)).e pharmacists." See Sept. 9,2008, Press Release (Ex. P). Both Plain.tiffs testified to hearing

Gov. Blagojevich say that pharma.cists with religious objections should find another profession.

The record in this case shows extensive commentary about the Plaintiffs from the Defendant and

their representatives.

From April 2005 until Apri.l2010) the first three versions of the Rule :focused solely on

contraceptives, and particularly emergency contraceptives. Although the current Rule applies to

all FDA-approved drugs, the focus on emergency contraceptives is still'apparent. The idea for a

broad.er law oCCUll'ed not because of any problems experienced with other drugs-in fact IPFPR

Secretary Adams testified that ther.e were no complaints about other drugs-but because Adams

saw a similar rule in an emergenoy contra.ceptives oase in the Ninth Circuit. Secret.ary Adams

acknowledged that be kept bj.s file OD. the new law under the heading "Plan B" (referring to a

brand-name for emergency oontraceptives) and that all of the articles in his files about the new

Rule concerned emergency oontraception. The candid testimony of Secretary Adams as a whole

showed the present Rule was drafted with the Plaintiffs in mind. Secretary Adams

acknowledged he was unaware of refusals to sell emergency contraception for any reason other

than religion. He further testified that he did not believe that religious views should determine

whe1her a pharmacy dispenses a particular drug.

TIle govemroent asserts that this Rule serves a com.pelling interest in timely access to

drugs. Yet the government also concedes that it had never done anything to advance its asserted

interest prior to April 2010. Even as to e)J].ergency contraception, the Court heard 110 evidence of

3

APR-05-2011 14:32

217

98Y.

P.04

04/85/2011 13:85 217

CIRCUIT

PAGE 05/08

a single person who ever was unable to obtain. emergency contra.ception because of a religious

objection. The testimony indicated the Defendants bad not been vigorously enforcing its pdor

rules. Nor di.d the govenunent provide any evidence that anyone was having difficulties fineting

willing sellers of over-the-colu1ter PlanB, either at phannacies or over the ilJtemet.

The Rule is also su.bject to a. bost of exceptions for what the government called "common

sense business realities." For example, it is pennissible to refuse a prescription if a phannacy

has made a business decision not to acquire certain equip'::nent or expertise, if the

pharmacist has a medical or legal or if a patieo.t is a few dollars short of the pdce set by

the phannacy. See 68 Ill. ADC 1330.500(e)(3)-(4), (1), (). And a specialized phannacy is

excused from selling drugs not carried in. "similar practice settings.'l See id at (e)(6).

No paranel exemption exists for pharmacists and phannacy own.ers barred by their

religion from participating ill sales of particular drugs. In. fact, although the law contains a

variance procedure providing for what the government called "individualized governmental

assessments," Secretary Adams testified. tb.8t he could envision a "whole variety" of reasons that

might be accepted, but he could not foresee a variance beiJ).g granted for. a religious

The evidence also showed that all of Plaintiffs' pharmacies are within either reasonably

close walking or driving distance to emergency contraception a.od that emergency

contraception is also available over the internet. For example, Kosirog's Chioago store has more

than a dozen competitors within three miles, and one witlulJ. three blocks. Vander Bleek's

Morrison store is a fE:w blocks from a public hospital that dispenses emergency contraception,

and has more than a dozen com.petitors within a fifteen-minute drive. The government conceded

that any health impact from Plaintiffs' religious objections would be miniJnal.

4

APR-05-2011 14:32

217

98Y.

P.05

04/05/2011 13:05 217

CIRCUIT

PAGE 06/08

1. Count I: lJIinois Healthcare Right of Conscience Act: The Rule violates

Plaintiffs' rights under the Conscience Act, which was designed to forbid the govemm,ent fTom

doing what it aims to do here: coercing individuals or entities to provide healthcare services that

violate their beliefs. See 745 ILCS 70/2, 70/5, and 70/10. The distribution of cOlJ,ttaceptives by

phannacists and phannacies clearly falls within the reach of the Act. See, e.g. 745 ILCS 70/3.

Plaintiffs and their pbannacies have memorialized their opposition to selling these drugs i)J

ethical guidelines and govemi)).g documents. The government cannot pressure them to violate

their beliefs. See, e.g., 745 ILCS 70/5, 70/10. The government may certai.nly promote drug

access, but the Act requires them to do so without coeroing unwilling providers. See 745 ILCS

70/2. In Van,dersand v. Wal-Mart Stores, Ille., 525 F. Supp 2d 1.052 (C.D. Ill. 2007), Judge Scott

concluded that, "any per.son, including [plaintiff Phannacist] who refuses to participate in any

way in providing mediation because of b.is conscience is protected by the Right of Conscience

Act." See id. At 1057. The language of the statute is clear. The Illinois Right to Conscience Act

applies to pharmacists and phannacies. The plain language of the statute makes it clear that

phamlacists and pharmacies are covered under the Illinois Right to Conscience Act.

Additionally, the Defendants argue the Plaintiffs have not proven that pharmacies have a

conscience under the Act. The Court finds the testimony of Plaintiffs, Vander Bleek and

Kosirog, to be persuasive on this issue. The evidence at trial established that the objections of

the individual Plaintiffs 8J),d their closely held cOIporations are essentially one and the same,

because the individual Plam,tiffs clearly set the policy and tightly control the day to day

opeJ:ations of their phal1;nacies.

2. Count IV: Illinois Religious Freedom Restoration Act: Plaintiffs have established

the existence of a substantial burden on their religion as to all ver.sions of the Rule. See Diggs 'V.

5

APR-05-2011 14:32

217

98% P.06

84/85/2811 13:86 217

CIRCUIT

PAGE 87/88

Snyder, 333 Ill. App. 3d 189, 195 (Ill. App. Ct. 5th Dist. 2002). The government has not carried

its burden of proving that forcing participation by these Plaintiffs is the least restrictive means of

furthering a compelling interest. See 775 lLCS 35/15. The government conceded that the Rule

is inapplicable to doctors, nurses and hospitals; despite admitting refusals by these parties would

cause the same harm as refusals by the pharm.acists. Moreover, the Rule allows pharmacies to

avoid selling drugs or to obtain variances for "common sellse business" reasons o ~ , e l ' than

religion. These facts are in direct contrast to the government's compelling interests argwn.en.t.

Nor has the govemment demonstrated narrow tailoring, or that there are no less restrictive ways

to improve access, such as by providing the drug directly, or using its websites, phon.e numbers,

and sigos to help customers find wilUl.lg sellers. The Rule therefore violates the Illinois

Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

3. Count VI: V.obion of Un_ted States Constitution. First Amendment Free

Exercise of Religion: The evidence at trial established a Free Exeroise violation beoause the

Rule is n.eithcr neutral nor generally applicable. TIle Rule an.d its predecessors were designed to

stop phannacies and pharmacists from considering their religious beliefs when deciding whether

to sell emergency contracepti,ves. The record evidence demonstrates the Rule and all prior rules

were drafted with pharm.acists and phannacy owners with religious objections to selling

emergency contraceptives in mind. This lack of neutrality requires a strict scrutiny test be

appHed to this Rule. FurtheJJ.P.ore, the law is not generally appli,cable. The Rule excuses

compliance for a host of "common sense business" reasons, but not for religious reasons. And

the variance process is, by the government's admission, a system. of individualized governmental

assessments that is available for non-religious reasons, but not for religious ones, even though

the government acknowledged that the proximity of will.ing competitors nearby Plaintiffs'

6

APR-05-2011 14:32

217

98% P.07

84/85/2811 13:86 217

CIRCUIT

PAGE 88/88

phannacies m,ade any health-related impact of their religious constraints unHkely. See Morr-

Fitz, 231 Ill. 2d at 501 ("[1]t can be ooncluded that granting variances in these kinds of cases

would eviscerate the whole purpose of the rule."); see also Lulcumi, 508 U.S. at 5 4 2 ~ 4 3 . \Vhere.

as here) "individualized exemptions from a general requirement are available, the government

may not refuse to extend th.at system to cases of religious hardship without compelling reason:'

Id at 537-38. Accordingly, the la.w is subject to the compelling interest test under the federal

Free Exercise clause, id at 537-38, and fails that test for the reasons set forth. above cOllceming

Illinois Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

4. Count VII: United States Constitution Fourteenth Amendment: The Court finds

the case law cited by the Plaintiffs to be distinguishable in this m:ea. The Court finds the

Plaintiffs have not met their burden of proof as to CouJ,J.t VII and judgm,ent is entered for

Defendants on this Count.

Relief: The Court finds and declares that the Rule is invalid on its face and as applied

under the J.llinois Right to Conscience Act, Illinois Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and is

unconstitutional on its face and as applied and is void under the First Am,endment. Plaintiffs

have demonstrated clearly ascertainable rights needing protection, that they will suffer

irreparable harm without all injunotion, and that have no adequate remedy at law. The Court has

balanced the interest of. the parties and finds for the Plaintiffs. Accordingly) Defendants and all

those acting in concert from them are hereby pennanently enjoi.ned from enforoing the Rule.

Accordingly, judgment is entered for the Plaintiffs and against the Defendants on Counts I, IVl

and VI ofthe Third Amended Complai.nt.

ENTER: _4-L-f-/..:JL-I-I-I-DJ--

I I

7

APR-05-2011 14:32

217

98X P.08

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Complaint - Resurrection v. Henyard Et Al - 3.5.2024Document188 pagesComplaint - Resurrection v. Henyard Et Al - 3.5.2024Tom Ciesielka100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Scottish Rite - Chiefs of Masonry by Barry J. Lipson 33°, PSPDocument13 pagesScottish Rite - Chiefs of Masonry by Barry J. Lipson 33°, PSPChiefOfMasonry100% (6)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Complaint For Violation of Civil Rights, Conversion, and Battery Against University of California, Santa Barbara and OthersDocument9 pagesComplaint For Violation of Civil Rights, Conversion, and Battery Against University of California, Santa Barbara and OthersTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Doe v. Boy Scouts of America and Chicago AreaDocument502 pagesDoe v. Boy Scouts of America and Chicago AreaTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Court Rules Contract a LeaseDocument4 pagesCourt Rules Contract a Leaserbv005No ratings yet

- Amit Shah Bail Gujarat HC PDFDocument51 pagesAmit Shah Bail Gujarat HC PDFkartikeyatannaNo ratings yet

- Natalia Realty v. DARDocument3 pagesNatalia Realty v. DARJen Sara VillaNo ratings yet

- "Paul and His Team" Book Media Kit)Document4 pages"Paul and His Team" Book Media Kit)Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Right to Counsel in Police Line-UpsDocument5 pagesRight to Counsel in Police Line-UpsJia FriasNo ratings yet

- CENIZA VS COMELEC Supreme Court Upholds Restriction of Voting RightsDocument1 pageCENIZA VS COMELEC Supreme Court Upholds Restriction of Voting RightsSonnyNo ratings yet

- Barangay Preliminary InjunctionDocument2 pagesBarangay Preliminary InjunctionRyan Acosta100% (1)

- People vs. QuiansonDocument2 pagesPeople vs. QuiansonTaJheng BardeNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff's Motion For Damages Declaratory Judgment and Injunctive ReliefDocument2 pagesPlaintiff's Motion For Damages Declaratory Judgment and Injunctive ReliefTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Chicago Map For March For Life Chicago 2021Document2 pagesChicago Map For March For Life Chicago 2021Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Minnesota Young Conservatives Club Sues School Over First Amendment and Flag Code ViolationDocument48 pagesMinnesota Young Conservatives Club Sues School Over First Amendment and Flag Code ViolationTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Action Order, Man Kwan NG v. Edward-Elmhurst Healthcare - 11.5.21Document2 pagesAction Order, Man Kwan NG v. Edward-Elmhurst Healthcare - 11.5.21Tom Ciesielka100% (1)

- John Mauck "Jesus in The Courtroom" Media Kit July 2017 InteractiveDocument4 pagesJohn Mauck "Jesus in The Courtroom" Media Kit July 2017 InteractiveTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Law Offices of Robert Sullivan: Amended Petition For Injunction (Ramaekers, Et Al. v. Creighton University)Document5 pagesLaw Offices of Robert Sullivan: Amended Petition For Injunction (Ramaekers, Et Al. v. Creighton University)Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- McgipDocument3 pagesMcgipTorrentFreak_No ratings yet

- Excerpt From Report of Proceedings, Man Kwan NG v. Edward-Elmhurst Healthcare - 11.5.21Document13 pagesExcerpt From Report of Proceedings, Man Kwan NG v. Edward-Elmhurst Healthcare - 11.5.21Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Jane Doe vs. Miller & Lancaster, P.C.Document7 pagesJane Doe vs. Miller & Lancaster, P.C.Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Edina YCC Fully Executed Settlement AgreementDocument6 pagesEdina YCC Fully Executed Settlement AgreementTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Edina High School Young Conservative Club Et Al v. Edina School District Et AlDocument48 pagesEdina High School Young Conservative Club Et Al v. Edina School District Et AlTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- The Vibrant Workplace Media Kit 2017Document4 pagesThe Vibrant Workplace Media Kit 2017Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- "Love Your Work" by Robert Dickie III Media Kit 2017Document4 pages"Love Your Work" by Robert Dickie III Media Kit 2017Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- LB 173, TestimonyDocument3 pagesLB 173, TestimonyTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- LB 173, Bad For Business, 2-8-17Document2 pagesLB 173, Bad For Business, 2-8-17Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Jane Doe vs. Jasmine's Day Care and Alejandra Contreras Filed ComplaintDocument4 pagesJane Doe vs. Jasmine's Day Care and Alejandra Contreras Filed ComplaintTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Federal Judge's Order That Congress' Subpoena For All Undercover Videos of Abortion Industry Is To Be HonoredDocument4 pagesFederal Judge's Order That Congress' Subpoena For All Undercover Videos of Abortion Industry Is To Be HonoredTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Illinois' #1 Family Attraction Caught in Abortion DebateDocument2 pagesIllinois' #1 Family Attraction Caught in Abortion DebateTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Daleiden-NAF-Ord ReORDER RE CONGRESSIONAL SUBPONEADocument1 pageDaleiden-NAF-Ord ReORDER RE CONGRESSIONAL SUBPONEATom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Thomas More Society Won An Appeal in Indiana Supreme Court On Behalf of Fishers Adolescent Catholic Enrichment SocietyDocument11 pagesThomas More Society Won An Appeal in Indiana Supreme Court On Behalf of Fishers Adolescent Catholic Enrichment SocietyTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Daleiden-NAF-Letter To Judge Re Congressional Subpoena and 2 Exh (DKT #152)Document13 pagesDaleiden-NAF-Letter To Judge Re Congressional Subpoena and 2 Exh (DKT #152)Tom CiesielkaNo ratings yet

- Thomas More Society Responds To Fargo School District: Approve Students For Life ClubsDocument2 pagesThomas More Society Responds To Fargo School District: Approve Students For Life ClubsTom CiesielkaNo ratings yet