Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adewole Olagoke - Current Issues in Forestry Poster

Uploaded by

Adewole OlagokeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adewole Olagoke - Current Issues in Forestry Poster

Uploaded by

Adewole OlagokeCopyright:

Available Formats

RECONCILING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION, CARBON STORAGE AND LOCAL LIVELIHOODS IN PROTECTED AREAS:

prospects for REDD+ in Nigeria

Adewole OLAGOKE

School of the Environment, Natural Resources and Geography, Bangor University, UK

BACKGROUND Forests are valued for multiple purposes at local, national and global levels; offering benefits such as carbon sequestration, and making significant contributions to national and local livelihoods, particularly in developing countries. The potential of protected areas (PAs) in meeting the criteria for implementation of the schemes for reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation plus forest enhancement (REDD+) in developing countries have been identified (Coad et al 2008). Protected areas provide case study for REDD, from which lessons can be learnt from experience on their success or otherwise in reducing deforestation and support for local livelihoods, as influenced by various management strategies (Campbell et al, 2008) . OBJECTIVE

To examine how the relationship among biodiversity conservation, carbon storage and local livelihoods influence the effectiveness on Nigerian PAs.

SUMMARY

The study evaluated the contributions of Nigerian Protected Areas (PAs) to biodiversity conservation, carbon storage, and the link between their long-term management and rural livelihoods to inform necessary management strategies, which could help in designing appropriate REDD mechanism.

RESULTS (cont.)

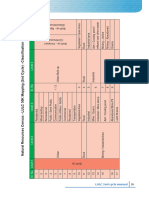

Nigeria falls within the West African biodiversity hotspot (Figure 1), with some species endemic to its boundary (Figure 2). Biodiversity is conserved within 972 protected areas into IUCN categories (figure 3). 1.11 Gt (15%) of the total 7.5 Gt Carbon in biomass and soils are found in the PAs, and ca. 20% of total carbon are in high density zones (Figure 4; Ravilious et al 2010).

Figure 4. Carbon distribution in Nigerian PAs

DISCUSSION

Local support, or resentment, for PAs is generally influenced by the perceived costs and benefits of PAs to communities (Ite 1996). Peoples resentment for existing management practices, and PAs managers laxity lessen the effectiveness of PAs in reducing deforestation. Trade-off to allow sustainable use and management of resources is the key. Collaborative planning and management with communities could offer a better solution.

METHODS

Information were extracted from: Review of published literature Extract from local media press release Local experts opinion personal experience.

RESULTS

Number of Known species 5000 4500 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 4715 119

CONCLUSIONS

Treating local livelihood issues with care, rather than heavy restrictions on local peoples activities, and improve governance are plausible to enhance the effectiveness of PAs in avoiding deforestation; making them suitable for REDD funding.

Ite (1997); Ite & Adams (2000)

100 % respondents 80 60 40

NGOs Community only Park & Community 65.6 34.4 Yes No Park only 0 20 40 60 80

Adetoro et al (2011)

Threatened species 27 9 889 274 2 154 0 109 2 684

20

0

Figure 6. % determination of development projects

Figure 5. Conservation benefits distribution

REFERENCES

1.Campbell et al (2008) Tropical Conservancy Biodiversity 9 (3 & 4): 117-121. 2.Coad et al (2008) Working Paper. UNEP-WCMC, UK. pp45

Figure 1. Biodiversity in Nigeria

Figure 2. Endemic sclater's monkey

CONTACT

Adewole OLAGOKE Bangor University, United Kingdom Email: afpc0d@bangor.ac.uk Phone: 07554306640

Livelihood benefits of PAs include infrastructural development, employment opportunity, alternative income sources like ecotourism, etc (Ite and Adams 2000; Ezebilo 2010), but not evenly distributed, and acceptable to all (Figure 5 & 6). The costs on communities range from resource use restrictions, loss of tenure right to displacement. In reaction, people have continued with resource utilization within the PAs illegally.

3.Ezebilo (2010) Int. J. Environ. Res., 4(3):501- 506

4.Ite (1996) Environmental Conservation 23 (4): 351 - 357 5.Ite and Adams (2000) J. Int. Dev. 12, 325- 342 6.Ravilious et al (2010) Preliminary Report .UNEP-WCMC, UK. pp12

40.86% 13.54%

45.60%

Catergories I & II Categories III, IV &V Category VI & others

Figure 3: Classification of the 972 designated protected areas

You might also like

- Farm Business Planning in KazakhstanDocument12 pagesFarm Business Planning in KazakhstanAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Organic Farm Business Plan SummaryDocument33 pagesOrganic Farm Business Plan SummaryAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Organic Farm Business Plan SummaryDocument33 pagesOrganic Farm Business Plan SummaryAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Farm-Business-Start-Up - Checklist-SkvarchDocument5 pagesFarm-Business-Start-Up - Checklist-SkvarchAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Business Plans For Agricultural Producers: Risk ManagementDocument5 pagesBusiness Plans For Agricultural Producers: Risk ManagementAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Growing Diversified Farm Business Through CSA ExpansionDocument14 pagesGrowing Diversified Farm Business Through CSA ExpansionAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Unit 2.0 Biz Plan PDFDocument50 pagesUnit 2.0 Biz Plan PDFAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Farm Business Planning in KazakhstanDocument12 pagesFarm Business Planning in KazakhstanAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- BusinessDocument51 pagesBusinessAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Business Planning Work Book Final 2013Document57 pagesBusiness Planning Work Book Final 2013Hitendra Nath BarmmaNo ratings yet

- Biotech To Boost Banana and PlantainDocument2 pagesBiotech To Boost Banana and PlantainAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Biotech To Boost Banana and PlantainDocument2 pagesBiotech To Boost Banana and PlantainAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication: Peking University May 6 2009Document91 pagesIntercultural Communication: Peking University May 6 2009Adewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Review Article Guidelines for Students on RotationDocument16 pagesReview Article Guidelines for Students on RotationZama MakhathiniNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication: Peking University May 6 2009Document91 pagesIntercultural Communication: Peking University May 6 2009Adewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document16 pagesChapter 3Adewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Poster Group C Monte Alto ReserveDocument1 pagePoster Group C Monte Alto ReserveAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Common Growth Models and Their Applications in PlantationDocument12 pagesCommon Growth Models and Their Applications in PlantationAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Tree Diversity AnalysisDocument28 pagesTree Diversity AnalysisAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Biovolume and Diveristy of Tree Species in Bitumen Producing Areas of Ondo State, NigeriaDocument21 pagesBiovolume and Diveristy of Tree Species in Bitumen Producing Areas of Ondo State, NigeriaAdewole Olagoke0% (1)

- Mangrove Forest Depletion, Biodiversity Loss and Traditional Resources MGTDocument7 pagesMangrove Forest Depletion, Biodiversity Loss and Traditional Resources MGTAdewole OlagokeNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- A tree is a producer. Bacteria can be decomposers. An eagle is a secondary consumerDocument37 pagesA tree is a producer. Bacteria can be decomposers. An eagle is a secondary consumerScience,Physical Education And Sports VideosNo ratings yet

- Sabah Biodiversity Outlook Ilovepdf CompressedDocument210 pagesSabah Biodiversity Outlook Ilovepdf CompressedMeenaloshini SatgunamNo ratings yet

- Algae Bloom PDFDocument4 pagesAlgae Bloom PDFElis Noviana HasibuanNo ratings yet

- ETP Parameters Testing and AnalysisDocument2 pagesETP Parameters Testing and AnalysisaliNo ratings yet

- Name: - Year 9 Biology - Ecosystems Practice QuestionsDocument6 pagesName: - Year 9 Biology - Ecosystems Practice QuestionsMaan PatelNo ratings yet

- DeforestationDocument3 pagesDeforestationTrisha Anabeza100% (1)

- Places - Threats To NatureDocument6 pagesPlaces - Threats To NatureJEEHAN DELA CRUZNo ratings yet

- Ecosystem Interactions Moderately Guided NotesDocument6 pagesEcosystem Interactions Moderately Guided Notesapi-527488197No ratings yet

- Questions Test 1Document2 pagesQuestions Test 1sarora_usNo ratings yet

- Concept Map HeiDocument11 pagesConcept Map Heiapi-298896805No ratings yet

- Biodiversity and EvolutionDocument20 pagesBiodiversity and EvolutionjeneferNo ratings yet

- Evs BookDocument184 pagesEvs BookChennaiSuperkings75% (4)

- Convention On Biological DiversityDocument7 pagesConvention On Biological DiversityKaran Singh RautelaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Science-Ch.3 - Community EcologyDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Science-Ch.3 - Community EcologyJes GarciaNo ratings yet

- Module 9 Taxonomy and EcologyDocument20 pagesModule 9 Taxonomy and Ecologyalucard xborgNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Hotspots in IndiaDocument20 pagesBiodiversity Hotspots in IndiaRajat VermaNo ratings yet

- Tamilnadu land market valuesDocument32 pagesTamilnadu land market valuesManiNo ratings yet

- Ecosystem PDFDocument32 pagesEcosystem PDFYuvashreeNo ratings yet

- Answers To CES CBT Test Online About Marine Environment AwarenessDocument41 pagesAnswers To CES CBT Test Online About Marine Environment AwarenessMyo Minn Tun100% (1)

- Test Inspire Science Grade 5 Unit 2 Module 2 Lessons 1-3 QuizletDocument7 pagesTest Inspire Science Grade 5 Unit 2 Module 2 Lessons 1-3 Quizletkay htut0% (1)

- Technical Manual LULC 2nd Cycle Classification by NRSC - IndiaDocument4 pagesTechnical Manual LULC 2nd Cycle Classification by NRSC - Indiaphdanupam22No ratings yet

- UploadDocument34 pagesUploadKimi DeolNo ratings yet

- Environmental Geography Land Use Survey in BandarbanDocument21 pagesEnvironmental Geography Land Use Survey in Bandarbanusrah SabaNo ratings yet

- Ecosystems On The Brink TextDocument6 pagesEcosystems On The Brink Textapi-239466415No ratings yet

- Lendi-Ziese T 190701Document58 pagesLendi-Ziese T 190701SARAKEYZIA ENJELIC AMELIA KAUNANGNo ratings yet

- Wetlands and Lakes ConservationDocument21 pagesWetlands and Lakes Conservationtushar goyalNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Wetlands - UIPE NTC June 2012Document75 pagesPresentation On Wetlands - UIPE NTC June 2012naed_designNo ratings yet

- State of Nature in The EU Results From R PDFDocument178 pagesState of Nature in The EU Results From R PDFjlbmdmNo ratings yet

- Balee 2006 - The Research Program of Historical EcologyDocument24 pagesBalee 2006 - The Research Program of Historical EcologyJuan VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Food Chain Grade 5Document16 pagesFood Chain Grade 5adam ferdyawanNo ratings yet