Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Educational Management Administration & Leadership-1999-Lumby-71-83

Uploaded by

Zara BhakriOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Educational Management Administration & Leadership-1999-Lumby-71-83

Uploaded by

Zara BhakriCopyright:

Available Formats

Educational Management Administration & Leadership http://ema.sagepub.

com/

Strategic Planning in Further Education : The Business of Values

Jacky Lumby Educational Management Administration & Leadership 1999 27: 71 DOI: 10.1177/0263211X990271006 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ema.sagepub.com/content/27/1/71

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

British Educational Leadership, Management & Administration Society

Additional services and information for Educational Management Administration & Leadership can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ema.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ema.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://ema.sagepub.com/content/27/1/71.refs.html

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

Educational Management & Administration 0263-211X (199901) 27:1 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi) Copyright 1999 BEMAS Vol 27(1) 7183; 006774

71

Strategic Planning in Further Education

The Business of Values

Jacky Lumby

Introduction

MANAGERS WITHIN further education have been subject to criticism both from those working in the sector and those observing from outside (Ainley and Bailey, 1977; Elliott and Hall, 1994), and stand accused of managerialisman ill-dened concept which seems to imply the inappropriate adoption of business values and practice. Strategic planning can be seen as exemplary of the adoption of managerialism, deriving as it does from corporate practice. Prior to 1993, colleges participated in a planning process which was led by the local education authorities (LEAs), intended to produce some coherence in the provision of post-compulsory education and training. Since incorporation in 1993, colleges of further education have been required to undertake strategic planning as independent institutions, encompassing not only curriculum issues but also aspects of planning such as human resources and premises which had previously been the formal responsibility of the LEA. In attempting a strategic view, harmonizing all assets and activity within a long-term plan, colleges have moved to a planning process much closer to that undertaken by independent businesses. A second aspect of the greater similarity to commercial strategic planning is the degree to which the absence of local coordination has resulted in a competitive environment which may be detrimental to current and potential students and may be of national concern (Kennedy, 1997). Crisp (1991: 3) denes the process: Strategic planning is the set of activities designed to identify the appropriate future direction of a college, and includes specifying the steps necessary to move in that direction. The generic literature abounds with reminders that strategic planning is a very complex and contested theoretical area. Both the Further Education Development Agency (FEDA, 1995) and the National Audit Ofce (1994) by inference adopt a rational approach in the guidance they offer colleges, and detail the failure of colleges to match the assumed features of this model, that is the achievement of a mission-derived hierarchy of precise and measurable objectives with clear timescales and responsibilities. This criticism has been balanced by the recognition that colleges have survived in a period of successive nancial cuts (FEFC, 1996a) and expanded their student numbers (FEFC, 1996b), indicating some success with their planning process. The Kennedy Report (Kennedy, 1997) discriminates between increased student numbers and widening participation, arguing that the current deregulated context may be leading to colleges increasing numbers in ways which still do not address the non-participation of the disadvantaged, implying criticism of the value base and methods of colleges.

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

72

EDUCATIONAL MANAGEMENT & ADMINISTRATION 27(1)

This article reports on interviews with principals in the context of analysis of a sample of college strategic plans, with the aim of further understanding how the process of strategic management has been experienced and understood in colleges, and to explore the relationship between colleges experience and generic models of strategic planning. It also investigates the values colleges bring to strategic planning, exploring whether there is evidence to support Kennedys concerns.

Research Method

As Ainley and Bailey (1997) point out, further education is undertheorized, and although there is a body of literature on applying corporate strategic planning concepts to the public services (Bryson, 1988; Wilkinson and Pedler, 1994), the parallel literature on further education is very sparse. An answer to the question posed by Wilkinson and Pedler (1994: 188), Is the strategic managerial task inherently different in public service? and more specically, inherently different in further education, requires an answer urgently, both to enrich the pool of theory from which managers in the sector can draw to guide practice, and also to act as a touchstone against which to judge the justication of those who criticize strategic planning in further education for not conforming, or for conforming too strongly, to business models. Bogden and Biklen (1992), in discussing the nature of qualitative research, emphasize the goal of better understanding human behaviour, and the use of participant perspectives to this end. The research reported in this article was concerned not just with the products of strategic management, the strategic plans themselves, but also with how those concerned created meaning within the process. To achieve this empathic perspective (Bogden and Biklen, 1992) interviews were conducted with four principals and one second-tier manager with particular responsibilities for strategic planning in colleges in ve counties in the Midlands and eastern regions of England. Three colleges were in cities and two in smaller towns in more rural areas. Given the reluctance of many colleges to speak about what they perceive as a very sensitive area, the interview respondents were a convenience sample of those who offered help to further the research. As such they cannot be taken as representative, if indeed representation is achievable in such a diverse sector, but the conformity or divergence of their views may offer clues as to how strategic planning has been experienced by those charged with leading the process. For convenience, this group will be referred to as the principals throughout the article. To balance this personal perspective, the author requested copies of the strategic plans of the 222 general further education colleges in England. There were 53 responses: 29 full strategic plans and 24 partial plans. It was therefore possible to analyse the content of full or partial plans of 24 percent of all general further education colleges in England. The scrutiny of plans was designed to offer an insight into the process of planning and the stated intentions of colleges which could be related to generic theory of strategic management and form a context for the interviews with principals.

The National Framework

College strategic plans must be negotiated with both the FEFC and the local Training and Enterprise Council (TEC). The FEFC (1992) has offered guidelines on the structure it expects in college strategic plans. Analysis undertaken centrally indicates that most colleges conform to the expectations (FEFC, 1996b). The FEFCs suggested approach is based on

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

LUMBY: STRATEGIC PLANNING IN FURTHER EDUCATION

73

classical Taylorist ideas of management (Taylor, 1911), with carefully identied aims and objectives and the allocation of responsibility and resources against numerically specied outcomes, but the technical inclusiveness veils a strategic vacuum. The FEFC is charged with ensuring the adequacy and sufciency of further education, so they have responsibility for the overarching mission. However, all of the principals felt that this was more evident in rhetoric than in fact. As one explained: They are charged with providing adequacy and sufciency. When you say to them what does this mean they do not know. I know they do not know because I have asked the question. The principals perceived the procedure of the FEFC to be to spot where a college was withdrawing provision in a curriculum area and then to consider if a response was needed: The only approach of the Funding Council is to wait until people say they are getting out and then say, oh that is a problem. Could we talk to you about perhaps staying in? Its not a pro-active approach. Its not sitting down and saying what is adequacy and sufciency. Have we got provision to match demand? Where do we need to be? The situation at the moment is for them to ask, well whos giving up? Do we need to patch the hole? Generic theory (Ansoff and McDonnell, 1990) suggests that the responsibility for the overall mission or vision is properly placed with the top level of the organization, and that subunits must plan within the overall strategic aims which relate to mission. Within further education, the national mission is not dened in a way which is meaningful, and the absence of such direction leaves colleges de facto with the task of achieving a national strategy in a context where there is no well-dened and agreed mission and where they have little power to shape resources. Kennedys (1997) concern about a lack of coherence seems borne out, but the suggested response of a greater degree of collaboration and partnership will not address the lack of a national mission dening adequacy and sufciency of further education provision. If the FEFC framework was not seen as much positive help at a strategic level, none of the principals felt it to be a constraint on their strategic thinking. Fitting the thinking into the planning framework was a secondary process: You have what you might call a technical constraint of having to try and think back and turning what you would do in terms of responding to need into a numerical format, putting so many students into each programme area, so there is a sort of constraint there but it is not a constraint on the way you think strategically. It is a constraint in terms of interpreting the strategic plan into something which satises the Funding Council. Similarly the TECs were not seen as a constraint on strategic thinking. As one principal explained, he did not believe that his local TEC had the quality of information which would allow it to challenge any of the colleges plans: From our point of view, I tried to involve the TEC from very early on this year, sent them an early draft, but I hadnt had a discussion with any one of them about it. They have simply written back saying we think it is lovely and heres your letter (of endorsement) and that has been the extent of negotiations with them. All of the principals felt that they would wish to take account of the FEFC and TEC as important players, and some had helpful and supportive relationships, but ultimately, they felt free to shape their colleges objectives.

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

74

EDUCATIONAL MANAGEMENT & ADMINISTRATION 27(1)

The Content of the Plans

The plans themselves were analysed to identify the range of terminology, how far the different levels of the plans related logically to each other, and the range of aims and objectives. This uncovered a semantic mineeld. At the level of expressing the overall corporate aims and objectives, colleges referred to vision, mission, values, strategic aims, corporate aims, objectives, targets, strategic tasks, key commitments, key themes, crucial objectives, critical success factors, outcomes for students, motto, signicant factors. There was no common usage of these words. In many plans there was a loose relationship between the different sections. Johnson and Scholes present a neat, logical sequence of planning in which each level relates to the previous one (see Figure 1, adapted from Johnson and Scholes, 1993: 13). This model

Figure 1.

assumes that the rst level of planning is a visualization or concept of where the organization wants to be which is strategy neutrali.e. the means to reach the desired state are not chosen. As the hierarchy descends, the means to reach the overall aims are chosen and become ever more specic, each dependent on the previous level. Whether this gure fully represents what happens outside education is contested elsewhere, but it certainly does not describe the majority of further education college plans that were analysed. First, the means chosen to achieve the ends were apparent in many primary statements of aims: overarching vision, mission and aims were not necessarily strategy neutral. Additionally the sections which came in sequence and had titles relating to the generic concept of a hierarchy of specicity, often were simple restatements of the same general aims. In other words the vision would give some general aims which might be restated in the values or mission or corporate aims. Whatever sections were called, they were not necessarily a further renement or specication of the previous section. They were more focused on rewording, nding new words to restate the same content as the previous sections. The plans often incorporated sections on quality, accommodation, etc., as suggested by the FEFC and also sometimes sections which related to the units into which the college was organized, such as faculty or programme areas. Cross-referencing was used by some colleges to try to retain strong connecting links between different parts of the plan, but there

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

LUMBY: STRATEGIC PLANNING IN FURTHER EDUCATION

75

were many examples where the multiplicity of sections were not clearly linked. It was often as if each individual or group of individuals, from governors through to programme area teams, had reworked the sections into statements which were all their own and which bore no strong connection to other parts of the plan. It would be easy to hold this up as a failure to achieve the logic and precision required by rational planning models, and indeed colleges new to the process may have struggled to keep control of the coherence of the overall plan. However, it may be that the contrast with a strictly rational approach points to a different need and a different way of working. All of the principals referred to the unimportance of the strategic planning document and the importance of the process. For four of the ve, the fundamental purpose of the strategic planning process was to identify the purpose of the college: It is actually about galvanising yourself into some conscious thought about what you are there to do. You have to say things to yourself and to each other if you are to be able to act purposefully. The key phrase in this statement is in italics (my emphasis). Strategic planning to this principal is not just about arriving at crisp rational aims, objectives and costed action plans, but about speaking to each other. The use of words is not to achieve unambiguous targets for action, but primarily to explore the values and understandings of those who are involved. This may involve a limited group, such as the senior management team, or the entire college community, but it is essentially a conversation, an exchange which is only secondarily designed to delineate action. Primarily, it is an act of union, designed to reinforce commitment and motivation. Although the language and structure of plans varied, the actual aims and objectives were very general and very similar from college to college. All of the corporate aims could be categorized under four headings: the product or curriculum market resources/costs capability building

The majority of plans had strategic aims of all four types and a generic list of college aims could be deduced (see Table 1).

Table 1. Product/curriculum Increasing the range of provision Increasing the exibility of provision Developing the quality of the curriculum generally Developing specic aspects of the curriculum such as guidance, assessment Equal opportunities Increasing retention and achievement Market Nature of customers, age, geographical location, ability Numbers of students Achieving a positive image in the eyes of actual/potential customers Resources/costs Increasing income Managing efciently and cost-effectively Improving accommodation Meeting FEFC targets Surviving long term Building capability Developing staff Developing partnerships with external organizations Developing information and communications technology Contributing to local economic growth Caring for employees Caring for the environment

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

76

EDUCATIONAL MANAGEMENT & ADMINISTRATION 27(1)

Of course, at a high enough level of generality, the strategic aims of all organizations would appear similar. Surviving long term is just such an aim. However, the wording of the college plans retained this level of generality often not just in the primary strategic aims but further into the plan, at those levels where one would expect specicity to distinguish one college from another in the way that one company might be distinguished from another in business. This raised another point of comparison with generic theory. In the latter, companies seek to acquire a competitive edge by differentiating themselves from others, particularly rivals within their market. As Peters (1989: 137) puts it: Dont just stand there, be something! Peterss argument is further developed to suggest that companies must strive to be not just different from others, but signicantly different. Colleges are clearly following the route of attempting to focus on product, costs and market, but this is not necessarily leading all of them to a signicantly differentiated position.

Making Strategic Choices

To explore further this indication that colleges were not necessarily seeking to distinguish themselves from each other, the principals were asked what strategic choices they felt their colleges had. There were apparent differences in opinion. One felt We have absolute freedom. Another explained that he did not feel that there were any true strategic choices at all: a hundred years before someone had sat in his ofce making decisions about the curriculum and probably someone would be undertaking the same task in a centurys time. The decisions were tactical. He argued that the only strategic decision was whether the college continued or not, and in this there was less choice than might be imagined, as he felt that if the college closed, the community itself would set up a college of further education, as it had set up the college a century before. The college would continue to exist as a service to the community whatever managers might deliberate. The only decisions were small ones concerning minor changes in the curriculum. Another principal echoed this strongly, arguing that the inheritance of a college shaped the choices it could make. All felt that other colleges might have greater choices, but the principals emphasized a primary commitment to the colleges local community. Where work was undertaken elsewhere, it was to access resources which could be brought back to that community. Our strategy is based on what we perceive to be our communities needs. We dene our catchment and we are primarily here to serve those within a 25 mile radius of any of our sites but we go beyond that for a reason, and again this is written in our policy, that if we deliver beyond that catchment area we are doing so to make money to bring back to our catchment area . . . We do not need a big competitive edge against our nearest college. Most of the people will come to us anyway. Where choices were made to work outside the colleges local area, they might be value and not just nance driven. For one rural college, the choice to engage with several national and overseas market niches was partly to put money back locally, but also to ensure that students were not trained in a parochial environment. Colleges which had a large local population were able to make choices within their local community, again, at least at the moment, based on values. One college, faced with costs of 12 million to offer the 1619 curriculum, and income of around 8 million, had chosen nevertheless to continue to provide for this group: Sticking with it would be a value driven decision. Sticking with it would be to say that the market is 1619 year olds and this college is about educating 1619 year olds and

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

LUMBY: STRATEGIC PLANNING IN FURTHER EDUCATION

77

that is the service that we wish to continue providing, even though we do so at some nancial cost. However I dont know how much longer I can continue to do this and let the buildings crumble around me. Market choices were possible, whether to adopt specialist areas with national or international recruitment, whether to concentrate on training the 1619 years olds or local employed people, or returning adults or to offer higher education, but all this was within the parameters of a primary commitment to local people. For some colleges, the need is to provide for as many of the local groups as possible: In the particular geographical location in which we operate i.e. largely a rural location, we have a particular responsibility to the communities in this rural area to provide the broadest curriculum portfolio. Underpinning the ability to achieve a sense of choice was the position in relation to resources. All of the colleges were engaged in activities which were designed to generate income to plough back into provision for the local community, but the difcult nancial position of some undermined strategic choice. The necessity to generate sufcient income to continue to survive may in effect dictate choice.

The Business of Values

The colleges then were engaged in choices, but not all of them in the sense which might be recognized in the commercial world. The drivers of strategy were fundamental commitments to the value of education and training and to the people of the local community. These factors would be followed even at nancial cost as long as the college could survive. The comment quoted earlier You have to say things to yourself and to each other is relevant in that the people working in further education colleges may not have recourse to developing a strategy of competitive edge or differentiated markets and products. They are a public service and, as such, work within different parameters, and may need to reinvent continually their basic commitment to an unglamorous and low-status world. One principal said the real challenge lay with colleges like his own, which had historically grown up by meeting the range of local needs not covered by schools or universities: The worst thing to be is a general purpose further education college . . . because almost certainly, the really distinctive things belong to some other institution. . . . I look at this college and we are transparent. The worst thing you can be is in the middle ground with nothing distinctive. . . . Lots of tiny little niches, that is where the strategic choices are, let us try a bit of this, let us not do that. Actually, in a big sense there is nothing particular, just lots of little tiny moves. How can the generic theory of strategic planning, with the need to achieve distinctiveness, be linked to this understanding, where the planning process is lots of tiny little moves in an organization which is transparent? Clearly, some general further education colleges are working in a context which is too different to business to nd such a theory either a helpful description of their experience or an appropriate basis to analyse the possibilities for further action. Compared to the logic and competitive drive of the theory, many of the college strategic plans appeared to be a muddle and lacking individuality. However, a minority of plans had a driving sense of direction with clear connections between sections, a logical development of a hierarchy of objectives and a strong sense of developing a distinctive market position. A hypothesis which emerged is that the difference in the nature of the plans may relate to

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

78

EDUCATIONAL MANAGEMENT & ADMINISTRATION 27(1)

the geographical and historical context within which each college worked. Where the inheritance or geographical position allowed, the college had a real sense of strategic choices. For example, colleges located in an east coast port were able to offer a very distinctive vision of supporting a European market and global exporting industries. Colleges in a declining rural area, with a thin population and little concentration of industry or similar challenging environments, may feel that they are constrained by the imperative to meet as wide as possible a range of needs, particularly of those in the local community who are often the socially excluded. Despite an acute awareness of nancial realities, values, not a competitive position, lay at the root of the choices or lack of them, and may also explain the language and structure of the strategic plans themselves. A colleges plan could therefore be based on the need to achieve a distinctive niche and the ability to drive forward hard in a logical and focused way, or on the need to use the strategic planning process to reafrm values and commitment to the needs of local people, a position which was not distinguished from other colleges, and where the creation of commitment overrides all other possible aims of strategic planning. Despite the accusations of managerialism, the principals interviewed gave a strong sense of a value-driven process: This is the difference between a college and a company. A company can make a strategic decision to get involved in a different area of activity, and to employ resources in different areas so that they will creep away from what their founders initiated to some other area. A college can avour education, but it cant strategically step away from it. . . . Why? What is the fundamental drive? Its because people want to learn, want to change. Viewed from this perspective, the purpose of strategic planning in further education may differ fundamentally from that in business.

The Process of Planning

The process of strategic planning was seen as difcult by all the principals. One described calculating the years of experience in education of those involved in formulating the strategic plan. It added up to a huge number and yet we cant get the projections right. Every year we get them wrong . . . We are asking the impossible. Two major issues were the difculty of securing adequate information and the most effective way of involving staff. Local information was universally seen as problematic and may remain a stumbling block for some time to come. The involvement of staff was a more complex problem. Ainley and Bailey (1997: 60) state: Strategic decisions are taken at the centre and these are passed for local implementation to middle managers in their specialist curriculum areas. This is one of the sources of the new managerialism in further education. Interviews were only conducted with senior managers and therefore the perspective of middle managers and lecturers was not included. However, it was quite clear that the practice was, at least in intention, more varied than indicated by Ainley and Bailey and that the simple equation of involvement good, imposition bad, was not seen as unequivocal. The plans themselves sometimes indicated that the process had not been topdown. Some college plans were produced by a synthesis of plans written by programme area teams. One plan noted that contributions had been sought from the whole community and 120 staff had contributed ideas. The whole issue was fraught with problems, as one principal explained:

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

LUMBY: STRATEGIC PLANNING IN FURTHER EDUCATION

79

How do you get an organisation of 400 people who are all working in different ways, in different sets of people within the organisation, and dont appreciate each others culture and values, to own something that is called a strategic plan? That is what all the models say you are supposed to do. He went on to dene his own position as disbelieving this as an absolute. He did not believe that all wished to make a contribution, nor that all could achieve an overview of the college. Speaking of the IT technicians as an example, he explained: I dont think they would ever say that they want ownership of the strategic plan. They want leadership and they want to make some contribution. They want to feel that their views are important even if they have no views to make and often they will have no views to make. So I am a bit confused about exactly what ownership is. The concept of ownership, if this meant everyone agreeing on aims and objectives and being fully committed to the plan, was seen as unrealistic. All of those interviewed had tried to involve staff to differing degrees. One had established a framework for every group from governors to programme area teams to be part of the process which was consensual not consultative. It was not a question of writing a plan and then sending it to people to comment. The plan was evolved through a collaborative process, each stage being agreed before the next was initiated. Other principals did use a consultation process, where the plan was written by senior staff, sometimes incorporating the ideas from a number of staff and other stakeholders, and then circulated for comment. Of the ve principals interviewed, one was committed to a collaborative approach. The others were attempting a consultative process: I am not advocating total involvement. We are not a democracy. We are an organisation in which some people will have more inuence in strategic planning than others, but we do want as much ownership as we can achieve and as much contribution as possible from different staff in formulating the plan.

Implementing the Plan

The difculties of involving staff in the formulation of the plan shade into the difculties of motivating them to implement it once formulated. The problem is widely acknowledged. Quinn (1993: 83) comments on executives who rely on the awesome rationality of their formally derived strategies and the inherent power of their positions to cause their organisations to respond. When this does not occur, they become bewildered, if not frustrated and angry. The plan itself was seen by the principals as of limited value, partly because if it encompasses targets that can be reached they may be too unambitious, and also because things change so fast that it is in a sense redundant from the moment it is completed. Nevertheless, the possibility of using it as a benchmark to guide and discuss progress emerged, though with some caution as to how far targets could be delegated in an endless succession like ripples emanating from the centre. While the use of objectives and targets was seen as helpful, the process of changing attitudes and behaviour as a result was seen as much more difcult. One principal described the challenge: Of course having a plan on its own does not mean anybody will do anything. . . . At some point during the working week the caretaker in this institution has to think that what he or she is doing is making some sort of contribution to the college plan. That may sound grand, but if I dont get them to the point where they think about their attitude to

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

80

EDUCATIONAL MANAGEMENT & ADMINISTRATION 27(1)

students, . . . if they dont at some point in their working week realise that they are not putting a brick in a wall they are building a cathedral, then the strategic planning has failed. It must touch peoples lives. In attempting to achieve this principals were building ownership processes, but also micropolitical tactics and coercion. The power base of players resulted in agendas which were not always perceived as in the best interest of the students or of the strategic management process. Some people just did not want to change. One principal described a programme area which was convinced it had as many students as it could possibly teach and was already a centre of excellence. He told them that they needed to teach more students and that they were not yet a centre of excellence: I had to tell them to do this. I listened to all their views as to why they could not and then I had to tell them to do it anyway. Questioned on how the staff had reacted, the principal answered: The nice answer would be that they were convinced by the arguments. The unpleasant answer is that they saw the need to do it or else. I think it was both. The staff had gone on to succeed in recruiting more students and improving quality. The means of achieving this were a mixture of coercion and reason, with a reorganization so that some individuals had new roles dependent on achieving what was planned. Not all agreed and it was acknowledged that they probably never would. Achieving a dominant view, in the words of the principal, was the aim: All the time I am after a dominant view and sometimes it can be through the force of argument, sometimes it will be through putting people who are supporting in positions of power. It sounds hard but it is one way of doing it and also making peoples career dependent upon their supporting the direction of the institution and making it clear that if they dont, they are along for the ride, but they are not moving anywhere in their own career. I dont believe I just said that, but it is true. Perhaps this could be seen as an example of the new managerialism cited by Ainley and Bailey (1997) The problem is that this is certainly not a new type of behaviour. The use of micropolitical activity was recognized for at least two decades before incorporation (Ball, 1987; Bolman and Deal, 1984). Consequently, whatever type of managerial behaviour it may be, it is certainly not new. The assumption that it is in some sense wrong is open to question. It is still not acceptable to openly admit to micropolitical behaviour, hence the nal sentence of the comment above, where the principal surprised himself at the openness of what had been said. There has been relatively little research in any phase of education into micropolitical behaviour, partly because of the inherent difculty of researching behaviour which is by denition hidden. The use of career prospects as a lever to create loyalty or direct behaviour is indisputably present in many institutions. It is therefore more likely that when college leaders are exhorted to achieve a consensual approach, they may need to consider how far the prevailing models of collegiality are a normative mythology and how far they may need to be modied into a more realistic approach, including a wider range of tactics. The need for all staff to be fully aware of and committed to the strategic plan was also questioned. One principal pointed out that, in wandering round the college, unless a senior manager was encountered, the staff met at random would probably disclaim all knowledge of the strategic plan: I think people are aware that changes are happening but they would not package it up and say oh thats because of the strategic plan. They would describe it as managers cutting budgets or attribute it to something else. The real need, as he saw it, was for managers at all levels to be able to interpret and draw out the important points and motivate people in the direction of the plan. The strategic plan was a failure if the behaviour

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

LUMBY: STRATEGIC PLANNING IN FURTHER EDUCATION

81

of teachers with students was not touched by it, but the behaviour would not be touched only by every member of staff being fully conversant with the plan and having fully contributed. The latter was certainly one way, and an important way to all of the principals, but it was not the only way. If a teacher changed what he or she did without realizing that it was as an indirect result of actions set in motion by the strategic plan, that was ne.

Conclusions

All of the principals agreed that engaging with strategic planning had brought benets to their college. They felt that the process had resulted in: a greater sense of purpose an increased feeling of independence a benchmark against which all decisions could be measured better systems and efciency better communication as there was something important to communicate

To use their words it had taken away the adhocery and provided a peg to hang everything on. There was admiration from one principal that the FEFC had forced colleges kicking and screaming into better practice. The picture that emerged did not support Kennedys criticism that the new ethos has encouraged colleges not just to be businesslike but to perform as if they were businesses (Kennedy, 1997: 3). Colleges had become more business-like, but not in any simplistic sense of being prot or competition centred. They were more sure and more committed to what their business was: Business-like means recognising who we exist for, who we are serving, who our clients are and measuring ourselves against the satisfaction of those customers/clients . . . so by business-like, I am not meaning that you have got to measure every success in terms of prot. In a public sector environment, as Wilkinson and Pedler (1994) point out, what may be required from strategic planning is a broad rather than detailed direction, so when writers analysing public sector plans from the perspective of private sector thinking criticize them as travesties (Argenti, 1992) because of their lack of detailed veriable objectives, it may reect misunderstanding. Equally, those who have criticized senior managers in the sector for managerialism may need to research further how far the behaviours in question are new or detrimental to the organization or the students. The planning context of a perceived strategic vacuum at national and regional level concerned the principals, and it may be that the new emphasis on developing regional partnerships (Department for Education and Employment, 1998) will address this problem to some degree. Such a development was cautiously welcomed: As resources get tighter we have to work in more partnerships, employers, the TEC, government bodies, other colleges, whoever, and it is getting understanding with them at a stage which could inuence our own planning. What tends to happen is that you issue plans to people which outlines this is what we are going to do instead of developing plans with people. There will be a bigger emphasis on that in the future. However the move from a free market towards a partnership model may be difcult as colleges balance their own desire to retain autonomy with the desire to achieve regional coherence and widen participation (Lumby, 1998).

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

82

EDUCATIONAL MANAGEMENT & ADMINISTRATION 27(1)

The process of strategic planning has provided a vehicle for colleges to engage in discussion as to what they are about and how they are to achieve it. For some, the purpose may be to identify ways of surviving in the face of aggressive competition, but for many general further education colleges, the process is different. There are certainly strategic choices, but they are small ones about shifts in how to meet the vocational education and training needs of their local people. The process of planning allows them to commit to this business and to become more business-like, that is more centred on how better to meet the needs of their students. The range of behaviours to achieve the plans may include micropolitical manipulation, but this has always been the case. Perhaps the real point is that there is now more chance of the purpose of such tactics being clearly understood and related to student need. Strategic planning in further education therefore differs greatly from that undertaken by private sector organizations in that the process is used to position not only, or in some cases not primarily, against competitors but against, in the words of one principal, governmental drift. Government has policies for schools and for higher education. Whatever is left over is further education, and against this grim scenario strategic planning had helped to maintain some sense of the worth and value of the work of the sector. Criticizing managers in further education for not conforming to private sector rational models or for implementing a business-derived inappropriate coercive regime is to underestimate the diversity of practice and to miss the opportunity to better understand and support those engaged in an almost impossible task.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement is made of the generosity of many colleges which provided their strategic plans, and of the principals who gave their time to share their experience.

References

Ainley, P. and Bailey, B. (1997) The Business of Learning. London, Cassell. Ansoff, H.I. and McDonnell, E.J. (1990) Implanting Strategic Management, 2nd edn. London: Prentice Hall. Argenti, J. (1992) Practical Corporate Planning. London: Routledge. Ball, S. (1987) The Micropolitics of the School: Towards a Theory of School Organization. London: Methuen. Bogden, R. and Biklen, S. (1992) Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. London: Allyn & Bacon. Bolman, L.G. and Deal, T.E. (1984) Modern Approaches to Understanding and Managing Organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Bryson, J. (1988) Strategic Planning for Public and Non-Prot Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Crisp, P. (1991) Strategic Planning and Management. Blagdon: The Staff College. DfEE (1998) Further Education for the New Millennium: Response to the Kennedy Report. London: DfEE. Elliott, G. and Hall, V. (1994) FE Inc.Business Orientation in Further Education and the Introduction of Human Resource Management, School Organisation 14(1): 7992. FEDA (1995) Implementing College Strategic Plans. London: FEDA. FEFC (1992) College Strategic Plans. Coventry: FEFC. FEFC (1996a) Quality and Standards in Further Education in England: Chief Inspectors Annual Report 199596. Coventry: FEFC.

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

LUMBY: STRATEGIC PLANNING IN FURTHER EDUCATION

83

FEFC (1996b) Analysis of Institutions Strategic Planning Information for the Period 199596 to 199798 (circular 96/02). Coventry: FEFC. Johnson, G. and Scholes, K. (1993) Explaining Corporate Strategy: Texts and Cases, 3rd edn. London: Prentice Hall. Kennedy, H. (1997) Learning Works: Widening Participation in Further Education. Coventry: FEFC. Lumby, J. (1998) Restraining the Further Education Market: Closing Pandoras Box, Education and Training 40(2): 5762. National Audit Ofce (1994) Managing to be Independent: Management and Financial Control in the Further Education Sector. London: HMSO. Peters, T. (1989) Thriving on Chaos. London: Pan. Quinn, J.B. (1993) Managing Strategic Change, in C. Mabey and B. Maynon-White (eds) Managing Change, 2nd edn. London: Paul Chapman. Taylor, F. (1911) The Principles of Scientic Management. New York: Harper. Wilkinson, D. and Pedler, M. (1994) Strategic Thinking in Public Service, in B. Garratt (ed.) Developing Strategic Thought. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill.

JACKY LUMBY,

Correspondence to: Educational Management Development Unit, The University Centre, Barrack Rd, Northampton NN2 6AF. [email: j.lumby@btinternet.com]

Downloaded from ema.sagepub.com at University of Warwick on August 4, 2011

You might also like

- @TradersLibrary2 Monster Stock Lessons 2020 202 John BoikDocument111 pages@TradersLibrary2 Monster Stock Lessons 2020 202 John BoikKartik Iyer91% (11)

- Value Investor Insight - Words of Wisdom PDFDocument43 pagesValue Investor Insight - Words of Wisdom PDFdmoo10No ratings yet

- Rowley Brussels-Rowley ShermanDocument27 pagesRowley Brussels-Rowley ShermanAkashdeep GhummanNo ratings yet

- B.ed ThesisDocument16 pagesB.ed ThesisBilal RazaNo ratings yet

- Issues of Strategic Implementation in Higher Educa PDFDocument28 pagesIssues of Strategic Implementation in Higher Educa PDFDanielNo ratings yet

- Issues of Strategic Implementation in Higher EducaDocument28 pagesIssues of Strategic Implementation in Higher EducaDanielNo ratings yet

- Principles of Effective ChangeDocument9 pagesPrinciples of Effective Changexinghai liuNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Strategic Planning in Higher EducationDocument50 pagesA Practical Guide To Strategic Planning in Higher EducationSyakinaMalekNo ratings yet

- Suma Parahakaran ICELDocument10 pagesSuma Parahakaran ICELDr Suma ParahakaranNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning and School Management Full of SDocument20 pagesStrategic Planning and School Management Full of SAnuradha KularathneNo ratings yet

- Researchrational Abcdraft FinalDocument6 pagesResearchrational Abcdraft Finalapi-437991476No ratings yet

- Etl Final ReportDocument20 pagesEtl Final ReportAŋdrés MeloNo ratings yet

- Educational Planning ModelsDocument10 pagesEducational Planning Modelsal WambuguNo ratings yet

- Americas Choice Final Proposal 5-19-09Document66 pagesAmericas Choice Final Proposal 5-19-09api-100385143No ratings yet

- F3F The Idea of Instructional Leadership in Engineerinfg EducationDocument4 pagesF3F The Idea of Instructional Leadership in Engineerinfg EducationMohd Shafie Mt SaidNo ratings yet

- Goals, Outcomes and CompetenciesDocument11 pagesGoals, Outcomes and CompetenciesRabiatul syahnaNo ratings yet

- Course Title: Cross Cutting Issues in Educational Management and Leadership Course CodeDocument5 pagesCourse Title: Cross Cutting Issues in Educational Management and Leadership Course CodeAbdella AhmedNo ratings yet

- 640 Response Paper 640Document11 pages640 Response Paper 640api-316746236No ratings yet

- Competence and Program-based Approach in Training: Tools for Developing Responsible ActivitiesFrom EverandCompetence and Program-based Approach in Training: Tools for Developing Responsible ActivitiesCatherine LoisyNo ratings yet

- Ed 230 - Reflections - BirinDocument10 pagesEd 230 - Reflections - BirinAyeshah Rtb NiqabiNo ratings yet

- Student OutcomesDocument42 pagesStudent OutcomesPuneethaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1096751611000510 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1096751611000510 MainRaluca Andreea PetcuNo ratings yet

- College Readiness Lit ReviewDocument4 pagesCollege Readiness Lit Reviewkaiwen100% (1)

- Challenges in Engineering Arab Education CurriculaDocument142 pagesChallenges in Engineering Arab Education CurriculaMarouen Ben AbdallahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Transformative Curriculum Design EDIT2Document50 pagesChapter 2 Transformative Curriculum Design EDIT2Noey TabangcuraNo ratings yet

- Complexity and Curriculum: A Process Approach To Curriculum-MakingDocument14 pagesComplexity and Curriculum: A Process Approach To Curriculum-MakingNana Aboagye DacostaNo ratings yet

- 39AdminHowison-NZCooperativehandbookDocument12 pages39AdminHowison-NZCooperativehandbookjoyelisadhty0906No ratings yet

- Zengeza ToeDocument5 pagesZengeza ToeMUTANO PHILLIMONNo ratings yet

- On The Origins of Competency in TrainingDocument41 pagesOn The Origins of Competency in Trainingعبد الحكيم المنگادNo ratings yet

- Issues Paper: IDSL 810 Critical Issues Ferris State UniversityDocument19 pagesIssues Paper: IDSL 810 Critical Issues Ferris State Universityapi-282118034No ratings yet

- Dynamicsof Curriculum Designand Development Juan Manuel MorenoDocument16 pagesDynamicsof Curriculum Designand Development Juan Manuel MorenoRovie SaladoNo ratings yet

- 'School Administrators' and Stakeholders' Attitudes Toward, and Perspectives On, School Improvement PlanningDocument20 pages'School Administrators' and Stakeholders' Attitudes Toward, and Perspectives On, School Improvement PlanningBilal RazaNo ratings yet

- Ed491548 PDFDocument17 pagesEd491548 PDFNguyen HalohaloNo ratings yet

- Lo3 Hesa 573 Writing Center - Si Tap Team A Final ReportDocument52 pagesLo3 Hesa 573 Writing Center - Si Tap Team A Final ReportCarol McFarland McKeeNo ratings yet

- Educational Planning-Article01Document9 pagesEducational Planning-Article01MAGELINE BAGASINNo ratings yet

- Connell & Klem - Theory of Change & Ed ReformDocument29 pagesConnell & Klem - Theory of Change & Ed ReformLucía GamboaNo ratings yet

- Cohort-Based Doctoral Programs: What We Have Learned Over The Last 18 YearsDocument20 pagesCohort-Based Doctoral Programs: What We Have Learned Over The Last 18 YearsAnonymous qAegy6GNo ratings yet

- Meredith I HonigDocument23 pagesMeredith I HonigSeptiandita Arya MuqovvahNo ratings yet

- Journal of Planning Education and Research: Planning's Core Curriculum: Knowledge, Practice, and ImplementationDocument13 pagesJournal of Planning Education and Research: Planning's Core Curriculum: Knowledge, Practice, and ImplementationenviNo ratings yet

- Ejasfas 1024106 AsfasfasfDocument13 pagesEjasfas 1024106 AsfasfasfAji DzulariefNo ratings yet

- Curriculum in DevelopmentDocument5 pagesCurriculum in DevelopmentEndang GolisNo ratings yet

- Student RecruitmentDocument12 pagesStudent RecruitmentyuanknNo ratings yet

- A Responsive/illuminative Approach To Evaluation of Innovatory, Foreign Language ProgramsDocument25 pagesA Responsive/illuminative Approach To Evaluation of Innovatory, Foreign Language ProgramsIrma Ain MohdSomNo ratings yet

- Educational Management Administration & Leadership 2013 Walker 405 34Document30 pagesEducational Management Administration & Leadership 2013 Walker 405 34John JonesNo ratings yet

- Vaideanu 1Document16 pagesVaideanu 1كَتَلِيْنٌ رَادُوٌNo ratings yet

- Developing Institutional Strategy: John PritchardDocument22 pagesDeveloping Institutional Strategy: John PritchardGabija PaškevičiūtėNo ratings yet

- Competencies For The 21st Century: Jurisdictional ProgressDocument13 pagesCompetencies For The 21st Century: Jurisdictional ProgressJackyDanielsNo ratings yet

- Competitive Strategies in Higher EducationDocument10 pagesCompetitive Strategies in Higher EducationsomyntNo ratings yet

- Social Demand Approachin Educational PlanningDocument10 pagesSocial Demand Approachin Educational PlanningGlen Grace GorgonioNo ratings yet

- School-Based Management in Latin America: Overcoming Inequality: Why Governance MattersDocument36 pagesSchool-Based Management in Latin America: Overcoming Inequality: Why Governance MattersInez HsuNo ratings yet

- Seven recommendations for creating sustainability educationDocument14 pagesSeven recommendations for creating sustainability educationUsama KhosaNo ratings yet

- Genteman N 1994Document16 pagesGenteman N 1994MuhammadFaisalNo ratings yet

- Independent Research Essay - Final DraftDocument8 pagesIndependent Research Essay - Final DraftandersonlmgNo ratings yet

- 5 Assumptons OJDLA PDFDocument7 pages5 Assumptons OJDLA PDFdaveasuNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument13 pagesCase StudySunny RajNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Evaluation: Questions Addressed in This Chapter Include The FollowingDocument26 pagesCurriculum Evaluation: Questions Addressed in This Chapter Include The FollowingSchahyda Arley100% (6)

- StrategicPlanningVersionElsevier másolataDocument10 pagesStrategicPlanningVersionElsevier másolataNémeth KrisztinaNo ratings yet

- Reeves Evaluating What Really Matters in Computer Based EducationDocument15 pagesReeves Evaluating What Really Matters in Computer Based EducationRicardo PegationNo ratings yet

- School-based Management in Latin America impacts inequalityDocument36 pagesSchool-based Management in Latin America impacts inequalityFerry FernandaNo ratings yet

- CILSS Resource Traces History and Growth of Competency-Based EducationDocument22 pagesCILSS Resource Traces History and Growth of Competency-Based EducationemisoareNo ratings yet

- Research in Pa1 110351Document29 pagesResearch in Pa1 110351Krisanta ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Leadership for Tomorrow: Beyond the school improvement horizonFrom EverandLeadership for Tomorrow: Beyond the school improvement horizonNo ratings yet

- New Insights Into Consumer-Led Food Product DevelopmentDocument9 pagesNew Insights Into Consumer-Led Food Product DevelopmentJohn Henry WellsNo ratings yet

- Case Study Fashion Enterprises ABCDocument2 pagesCase Study Fashion Enterprises ABCArun KCNo ratings yet

- ScriptDocument2 pagesScriptJOANNE MICHELLE CASTIBLANCO FERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Product MarketingDocument4 pagesProduct MarketingJolina AnitNo ratings yet

- BBA II SEM III Cost Accountancy PPT 1Document22 pagesBBA II SEM III Cost Accountancy PPT 1Nishikant RayanadeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Feasibility PlanningDocument31 pagesChapter 3 Feasibility Planningrathnakotari63% (8)

- CBSE Marketing Sample Paper for Class XII Session 2022-23Document7 pagesCBSE Marketing Sample Paper for Class XII Session 2022-23Sg100% (1)

- A Standard Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) Model in GAMSDocument79 pagesA Standard Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) Model in GAMSMohammad MiriNo ratings yet

- Understanding Futures, Forwards, Options and Hedging StrategiesDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Futures, Forwards, Options and Hedging Strategiesjohndoe1234567890000No ratings yet

- Rajiv Bajaj - Axis PresentationDocument14 pagesRajiv Bajaj - Axis Presentationkittu99887No ratings yet

- Digital Marketing Strategy in Automotive SectorDocument99 pagesDigital Marketing Strategy in Automotive SectorTrumpet MediaNo ratings yet

- Audit of InvestmentDocument5 pagesAudit of InvestmentRodwin DeunaNo ratings yet

- Designing A Hybrid AI System As A Forex Trading Decision Support ToolDocument5 pagesDesigning A Hybrid AI System As A Forex Trading Decision Support Toolhamed mokhtariNo ratings yet

- Structure of Interest Rates ComponentsDocument2 pagesStructure of Interest Rates ComponentsƎdibern Lester Primo Destura0% (1)

- Preparation of WPPDocument16 pagesPreparation of WPPae etdcNo ratings yet

- SLM-19667-BBA - Fiancial Markets and InstitutionsDocument155 pagesSLM-19667-BBA - Fiancial Markets and InstitutionsMadhusudanNo ratings yet

- EC2066 Commentary 2006 - ZADocument13 pagesEC2066 Commentary 2006 - ZAtabonemoira88No ratings yet

- MBA 3 Sem Finance Notes (Bangalore University)Document331 pagesMBA 3 Sem Finance Notes (Bangalore University)Pramod AiyappaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management: Group MembersDocument30 pagesStrategic Management: Group MembersmaharNo ratings yet

- Is JCPenney Killing Itself With A Failed StrategyDocument3 pagesIs JCPenney Killing Itself With A Failed StrategyEmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Valuing Dot ComsDocument10 pagesValuing Dot ComsMarcela CwNo ratings yet

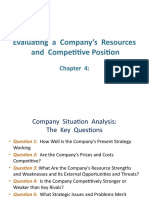

- 4 - Evaluating Companys Resources and Competitive PositionDocument53 pages4 - Evaluating Companys Resources and Competitive PositionNasir HussainNo ratings yet

- Globalization WorksheetDocument5 pagesGlobalization WorksheetGeanfranco Infantes100% (1)

- Factor Affecting Digital Payment Kiran GajjarDocument12 pagesFactor Affecting Digital Payment Kiran GajjarKRIANNo ratings yet

- Diversified Business Groups and Corporate RefocusiDocument26 pagesDiversified Business Groups and Corporate RefocusiAch Firman WahyudiNo ratings yet

- B.A (H) Business Economics-Semester V Security Analysis and Portfolio Management Unit Iv: Class Assignment # 1Document5 pagesB.A (H) Business Economics-Semester V Security Analysis and Portfolio Management Unit Iv: Class Assignment # 1pjNo ratings yet

- Bens HOPP Spreadsheet - Version 4.0Document8 pagesBens HOPP Spreadsheet - Version 4.0Yash SNo ratings yet

- Form PDF 166390820121221Document38 pagesForm PDF 166390820121221SethuramanNo ratings yet