Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Andersson (2011)

Uploaded by

Gabi AppelOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Andersson (2011)

Uploaded by

Gabi AppelCopyright:

Available Formats

The Policy Press 2011 ISSN 2040 8056

43

Organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour in nonprofit organisations: an empirical exploration

Fredrik O. Andersson

Despite growing aspirations from policy makers and institutional donors to generate and support a more entrepreneurial nonprofit sector, we still know little about what characterises an entrepreneurial nonprofit organisation. This study utilised data from 50 small- and medium-sized nonprofit agencies to explore empirically organisational capacities associated with entrepreneurial and less entrepreneurial nonprofit agencies. The results indicate that features linked to financial and top management leadership capacity are on average stronger in entrepreneurial agencies. While this study cannot determine causality, it provides a rare comparative perspective to help inform future efforts to build and understand entrepreneurial nonprofit organisations.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Introduction

Social entrepreneurship is a concept and practice that has generated an engaging discussion contesting several existing assumptions about civil society (Eikenberry and Kluver, 2004) and nonprofit organisational practices (Dart, 2004). Despite the absence of a single and clear definition and understanding of social entrepreneurship, many foundations and philanthropists such as the Skoll Foundation and Schwab Foundation have been eager to help develop and support socially entrepreneurial activities. In addition, public policy makers are also recognising the potential of social entrepreneurism as evident by the recent establishment of the United States (US) Office of Social Innovation and Civic Participation, which is devoted to the specific task of stimulating and catalysing entrepreneurial approaches to address old and new social issues. On the other hand, nonprofit managers and agencies are feeling increased normative pressures to be more entrepreneurial as success, and even survival, demands that nonprofits operate more like for-profit organisations, seeking competitive advantage through innovation (McDonald, 2007: 256). In contrast to the rapid pace by which social entrepreneurship has been adopted by nonprofit practitioners and donors, social entrepreneurship research is still in its infancy (Light, 2008). Despite a growing number of academic articles, the field remains narrowly focused. In a recent meta-analysis of the literature, Hill et al (2010: 6) found that definitional, conceptual and case studies dominate current scholarly work and observed that the social entrepreneurship literature is notable for its lack of empirical work. Such scarcity suggests that academics are having a difficult time informing and advising nonprofit practitioners, donors and policy makers about

Key words nonprofit organisations entrepreneurship organisational capacity

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

research

44

Fredrik O. Andersson

relevant and important socially entrepreneurial issues and practices. Put differently, our collective knowledge of what characterises a socially entrepreneurial nonprofit agency or what makes socially entrepreneurial nonprofits succeed or fail is still very limited.Whether this represents a serious problem or not is disputed. Certain scholars contend that entrepreneurship in the nonprofit sector should be treated predominantly as an application and transfer of private sector business practices and discipline into nonprofit agencies (Dart, 2004), making the issue of prescription and normative policy less complicated. Others argue that the nonprofit organisational form and structure pose specific opportunities and challenges when it comes to being entrepreneurial, suggesting that the intersection between nonprofit and entrepreneurship scholarship is both wider in scope and more complex in nature (Kistruck and Beamish, 2010). In recent years, several streams of social entrepreneurship research have started to move beyond conceptualisation as scholars are now calling for more theoretical rigour and empirical analysis to establish and develop social entrepreneurship as a legitimate academic domain (Short et al, 2009). To engage in such progressive research, this paper will employ an emerging behavioural approach that depicts entrepreneurship in nonprofit agencies as a set of specific organisational behaviours, that is, innovation, proactivenss and risk-tolerance (Morris and Joyce, 1998; Mort et al, 2003;Voss et al, 2005; Helm and Andersson, 2010; Pearce et al, 2010). This stream of behavioural research is still at a nascent stage but represents one of few empirical and multidimensional frameworks for investigating entrepreneurship in nonprofit organisations that is not restricted to anecdotal evidence or case-study methodology. In addition, this characterisation can include but is not limited to behaviours related to income-earning activities, and this separates it from the notion of social enterprise that generally includes an earned income component. By examining entrepreneurial behaviour (rather than enterprising activities) in small- and medium-sized nonprofit human service organisations located in a large Midwestern metropolitan area, this research seeks to explore a fundamental yet simple question: what differentiates highly entrepreneurial from less entrepreneurial nonprofit agencies? More specifically, this research will explore this question by examining differences in nonprofit organisational capacity in entrepreneurial and less entrepreneurial organisations.While many scholars have proposed that such capacity differences do exist (Brinckerhoff, 2000; Sadler, 2000; Dees et al, 2001), little empirical and/or comparative evidence exists to support such claims. Organisational capacity also represents a main area of interest for many funders, nonprofit boards and managers that seek to build high-performing nonprofit agencies (Light and Hubbard, 2004). Hence, insights into the type of question addressed in this paper will not only support academic progress of social entrepreneurship research but will also respond to needs and interests expressed by practitioners. The next two sections introduce the behavioural social entrepreneurship approach and discuss previous research emphasising the relation between entrepreneurship and nonprofit organisational capacity.The following section describes the data collection process, key variables and methods.The subsequent section presents the data analysis and results. The next section highlights and discusses the results, implications and limitations of the study and suggests ideas for further research. The final section concludes the paper.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

Organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour ...

45

Social entrepreneurship

There is currently no unified theory of social entrepreneurship, which has resulted in a rich and diverse field of research covering multiple means, ends and levels of analysis (Light, 2008). In an influential article, Stevenson and Jarillo (1990) proposed that one way of dealing with such an overwhelming breadth and depth of entrepreneurship scholarship is to divide research into three categories: causes of entrepreneurship, effects of entrepreneurship and behaviours of entrepreneurship. Based on this categorisation, Stevenson and Jarillo advised that the behavioural approach represents the most relevant option for managerial- and organisational-level entrepreneurial research. One influential behavioural approach found in the business entrepreneurship literature focuses on how strategy-making processes inside business enterprises generate a foundation for entrepreneurial decisions and actions. Labelled entrepreneurial orientation or EO, this framework represents one of the most widely accepted and utilised theoretical and empirical constructs in entrepreneurship research, in particular when it comes to examining entrepreneurial differences between firms or comparing different levels of EO with other key variables such as performance, growth or other contingency variables (Covin et al, 2006; Rauch et al, 2009). The utility of the behavioural approach has in addition been recognised in social entrepreneurship scholarship (Morris and Joyce, 1998; Mort et al, 2003; Mair and Marti, 2006;Weerawardena and Mort, 2006). By adapting, reformulating and testing the core constructs from the business-based EO construct to fit not-for-profit agencies, several scholars have established support for the view that social entrepreneurship can be conceptualised and empirically tested as a multidimensional behavioural construct in the nonprofit sector.This construct concentrates on the process and level of social entrepreneurship, that is, the extent to which nonprofit agencies innovate, behave proactively and handle risk (Voss et al, 2005; Morris et al, 2007; Helm and Andersson, 2010; Pearce et al, 2010). Such an approach has the advantage of focusing on organisational practices, processes and characteristics, which in turn permits investigations of how organisations foster entrepreneurship and how these behaviours change, influence and are influenced in nonprofit agencies. Furthermore, this approach portrays social entrepreneurship as a process that may or may not include an earned income component. In other words, social entrepreneurship and social enterprise cannot or should not be utilised interchangeably (Light, 2008). Finally, the adaptation of EO to nonprofit research represents one of the few areas of social entrepreneurship research where a cumulative and empirical body of knowledge is developing due to a strong theoretical foundation and established and tested measures.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Organisational capacity and social entrepreneurship

Capacity is an intuitive yet complex concept to comprehend. In its simplest form, organisational capacity is the enabling factor or the means to an end: more organisational capacity permits a nonprofit to grow, develop and improve as an organisation. Also, one way to understand differences in the impact and scale of nonprofit activities is to point out that different nonprofits enjoy different levels of

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

46

Fredrik O. Andersson

organisational capacity (Cairns et al, 2005). However, organisational capacity is also fuzzy because it is difficult to conceptualise as one thing, it is difficult to capture and measures changes in capacity, and it is difficult to know what, when and where capacity matters the most for organisations at different life-cycle stages (Stevens, 2001; Light and Hubbard, 2004; Strichman et al, 2008). As mentioned earlier, nonprofit scholars have proposed that entrepreneurial nonprofits are expected to have a different set or different levels of organisational capacities compared to their less entrepreneurial peers (Light, 2008). In particular, those who link nonprofit entrepreneurial behaviour with financial capacity have long argued that entrepreneurial nonprofit agencies will be more economically sustainable and possess a greater competitive advantage (see, for example, Boschee, 2006; Brinckerhoff, 2000). However, behavioural research suggests that the relationship between entrepreneurial nonprofits and performance is far from clear. Pearce et al (2010) found a positive relation between entrepreneurial nonprofit behaviour and economic performance in congregations whereas Morris et al (2007) found no support between economic performance and levels of entrepreneurial behaviour in 145 organisations. Other empirical inquires even indicate that entrepreneurial nonprofits are less likely to use diversified income streams including earned income (Light, 2008). There are other areas where scholars have investigated the overlap between entrepreneurial behaviour and nonprofit organisational capacity. In an empirical study of 260 nonprofit hospitals, McDonald (2007) concluded that organisations with high levels of mission capacity, that is, agencies with clear, specific, inspiring and compelling understandings of mission, visions and values, are more innovative. Morris et al (2007) investigated 145 nonprofits in a metropolitan area in Upstate NewYork and found that governance capacity, as defined by board activism, was positively related to nonprofit entrepreneurial behaviours since active boards set expectations, hold entrepreneurial nonprofit managers accountable and are active in the search for entrepreneurial ideas. Even though the above inquiries did not include identical constructs for the dependent and independent variables, these studies do point to one key implication: organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour appear to be related although it is difficult to pinpoint exactly how.While further conceptual and theoretical work is needed, it is also clear that more empirical insights are required to develop an understanding of the linkages between entrepreneurship and capacity in nonprofit organisations. In particular, we need to collect and compare data that simultaneously captures entrepreneurial levels and different levels of nonprofit organisational capacity. This process is outlined in the next section of the paper.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Data and methods

Data were collected from a group of 88 small- and medium-sized community-based nonprofit organisations in a large Midwestern metropolitan area. The majority of these organisations can be defined as human service agencies but the sample also included arts and culture, educational and environmental organisations. All agencies participated in a half-day workshop arranged by two local community outreach/

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

Organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour ...

47

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

research centres.Two individuals from the management/governance team represented each organisation (typically the executive director and the chair of the board). Helm and Anderssons (2010) nonprofit entrepreneurship instrument was used to capture the entrepreneurial behaviour of the agencies. To capture organisational capacity, each organisation filled out a customised capacity assessment tool originally developed for Venture Philanthropy Partners (VPP) by McKinsey & Company (VPP, 2001). This tool has been employed by several grant-making organisations to better understand and capture strengths and weaknesses of nonprofit organisational capacity (Guthrie and Preston, 2005). Each organisation was handed one copy of the two questionnaires and the management and board representatives were instructed to fill out the nonprofit entrepreneurship instrument jointly. A major benefit of such knowledgeable respondents working together is that it ensures more accurate data. For the capacity assessment, organisations were given multiple copies of the questionnaire for board and staff members to fill out over the following four weeks. In some cases, the organisation ended up providing one joint instrument. In other cases, multiple questionnaires were returned and the researcher added and averaged the responses. All participating nonprofits were encouraged to talk with, call or email the principal researchers with questions and/or requests for clarification. In total, 75 questionnaires were returned. The agencies also provided financial information (including their federal tax returns or Form 990 budgets and audits) and organisational character data (age, number of employees, board size etc). After the questionnaires were received they were thoroughly reviewed for problems and completeness, resulting in a final sample of 69 organisations. Several small agencies had not filed any 990 forms. To obtain the annual earnings of these organisations, they were contacted via telephone and/or email. Other discrepancies were also addressed via follow-up telephone calls and email correspondence.

Variables

The three nonprofit entrepreneurship constructs innovation, proactiveness and risk taking were measured using an instrument developed by Helm and Andersson (2010). The instrument consists of 10 items based on a semantic differential format and each item requests the respondent to consider their answers for the entire organisation, including all staff, the board of directors and volunteers, in both present time and during the previous five years (for a full description of the three constructs and detailed information about each item, see Helm and Andersson, 2010). According to Guthrie and Preston (2005), the VPP capacity tool has often been adjusted and altered depending on the organisation conducting the capacity survey. The version used in this research started with 11 cluster categories consisting of multiple items to be rated by the respondents on a scale from level 1 to level 4. A level 1 score indicates that there is a clear need for increased capacity for this element, level 2 indicates a basic level of capacity in place, level 3 that there is a moderate level of capacity in place and level 4 that the agency has a high level of capacity in place for this element. The differences between the different levels are described in detail for each item (see VPP, 2001). Two alterations were made: (a) one cluster was removed

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

48

Fredrik O. Andersson

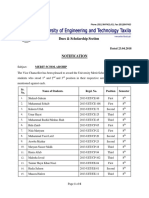

because it consisted of only one item and (b) the cluster Mission, Vision, Strategy and Planning, the biggest cluster with 16 items, was divided into two distinct clusters: Mission and Vision, and Strategy and Planning. While both are viewed as essential elements of capacity (Light and Hubbard, 2004; Strichman et al, 2008), they are distinct in so far as an agency can possess high levels of capacity in terms of mission and vision but not necessarily in terms of strategic planning. Ultimately, 11 capacity clusters were included and these are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Capacity areas

Capacity cluster 1 2 Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press 3 4 Mission & Vision Strategy & Planning Programme Design & Evaluation Human Resources Number of items 4 12 5 10 Example of area content Clarity and specificity of agencys reasons for existence and aspirations Existence of clearly defined medium- to long-term strategy, goals, performance targets and operational plan Existence of comprehensive and integrated systems for capturing agency performance and progress Existence of plans for recruitment, development and retention of staff. Clarity of staff roles and existence of incentive systems Experience and competence of top managers: ED, CFO etc. Ability to lead and handle a double bottom line Existence and usages of electronic database systems for tracking client, staff, programme outcomes, financial information etc Existence of financial plans and robustness of financial systems and controls Bottom line and cash flow situation. Usage of financial data and forecasting. Diversity of funding sources Existence of fundraising competence and fund development planning Role and involvement of the board in strategic planning and fund development. Existence of board recruitment plans, board orientation and training opportunities Existence of marketing and/or communication plans. Use of partnerships and presence/involvement in community

5 6

Top Management Team Leadership Information Technology

8 4

7 8 9

Financial Management Financial Systems & Position Fund Development

2 5 4 6

10 Board Leadership

11 Marketing, Communications & External Relations

Method

A principal component factor analysis with an oblique rotation (promax) technique was conducted to assess the proposed entrepreneurial behavioural constructs. This is an appropriate method since previous research suggests that the three behavioural constructs would co-vary, and by using a promax rotation the factors are permitted to correlate with each other (Wiklund and Shepherd, 2005; Covin et al, 2006). Given the exploratory nature of this research, a second step was implemented following an approach taken by Light (2008) that divides the sample into groups. The behavioural entrepreneurship approach does not define nonprofit agencies in

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

Organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour ...

49

entrepreneurial/non-entrepreneurial terms but provides a composite score along a continuum. As the primary interest is to compare and contrast the capacities of more entrepreneurial with less entrepreneurial nonprofits, all organisations were ranked based on their nonprofit entrepreneurship composite score and, thereafter, the top and bottom were isolated to create two groups of 25 agencies each. Given that a key aspect of exploratory inquiry is to distil and determine what novel ideas might be generated from something previously unexplored, taking out the middle segment allows for a more distinct interpretation of similarities and differences between organisations. Of course, reducing an already small sample can hardly be viewed as a desirable procedure but because this is not confirmatory research this approach is appropriate.To explore the capacity make-up of the entrepreneurial and less entrepreneurial groups of nonprofit agencies, t-tests were conducted for each capacity cluster.

Data analysis and results

The first step was to investigate whether the three behavioural constructs were distinct from each other. All three behavioural nonprofit entrepreneurship (NPE) factors innovation, proactiveness and risk taking loaded on separate factors and the item factor loadings were all above 0.7.The three factors emerged using a promax rotation that allows for correlation between the factors but no large cross-construct factor loadings were detected, which indicates the existence of three distinctive behavioural dimensions.Taken together, the three factors accounted for approximately 70% of the total variance. These results confirm and are consistent with Helm and Anderssons (2010) original findings. A second step was to investigate the reliability of each behavioural construct. Using Cronbachs alpha it can be determined to what extent the items in each construct are interrelated to one another. A common recommendation for organisational research is that an alpha level above 0.7 is considered desirable (Peter, 1979) and all of the constructs had levels above this threshold. Finally, previous work has suggested that the salient constructs should be correlated, and all of the entrepreneurial behavioural constructs in this sample portrayed significant correlations. Thus, the three constructs could be combined and analysed as a single NPE construct (Morris et al, 2007; Helm and Andersson, 2010). The next section describes the sample organisations in more detail. From a financial viewpoint, a majority of the 50 agencies could be defined as small (median annual revenue = US$117,958) with the exception of five organisations with annual revenues above half a million dollars. On average, entrepreneurial agencies were bigger (mean annual revenue = US$236,667) than less entrepreneurial organisations (mean annual revenue = US$109, 807) and a t-test indicated that this difference between the two groups was significant (p = 0.047). However, given the small number of cases and variance within each group this finding must be viewed with a large portion of prudence. For example, Helm and Andersson (2010) did not find any significant relation between revenue and NPE. Still, existing entrepreneurship research does indicate that financial resources can matter in the entrepreneurial process, especially when it comes to innovation (Sorescu et al, 2003). The role of financial resources will be discussed further later.Table 2 provides descriptive statistics of the two groups;

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

50

Fredrik O. Andersson

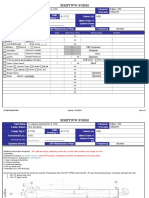

it indicates that entrepreneurial organisations were bigger (larger average staff size), older and had larger volunteer pools, although not significantly so.Table 2 also shows each of the three entrepreneurial behaviour scores alongside overall NPE scores. As expected, t-tests revealed that there were statistically significant differences between the two groups for all of the subconstructs and the combined NPE construct. Table 3 presents the results of the difference of means tests for each capacity cluster.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics and NPE scores

Entrepreneurial group Mean Age Board size Number of volunteers Number of staff Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press Innovation Proactiveness Risk taking NPE

Note: *** p < 0.01.

Less entrepreneurial group Mean 11 9.27 27 1.6 4.1 4.3 3.3 11.7 s.d. 8.5 4.5 19.5 2.3 1.5 1.3 1.1 1.9

Significance *** *** *** ***

s.d. 11.4 4.0 29.9 2.5 0.9 1.0 1.1 1.4

16 9.56 40 3.1 6.4 5.7 5.2 17.4

Before moving on to a discussion about implications and further research, I want to highlight some of the key limitations of this study. As already mentioned, a small sample size in combination with a narrow set of small/medium-sized nonprofit organisations clearly limits any attempts to reach more wide-ranging conclusions. Second, the subjective nature of the self-reported capacity ratings was not backed by the collections of any additional organisational measures and thus may include hidden biases. Finally, the method utilised in this paper only portrays differences between groups. In other words, we do not know what direction the causality flows between organisational capacity and nonprofit entrepreneurial behaviour. Despite these limitations, this research depicts some interesting findings that are discussed next.

Discussion

Overall, both groups portrayed basic to moderate levels of capacity in the majority of the capacity clusters. In other words, most agency representatives reported that there was room for capacity improvements in their organisations.The absence of higher (ie close to an aggregated score of 4) levels of capacity was not altogether unexpected given the relative smallness of the sample agencies. Both entrepreneurial and less entrepreneurial nonprofits depicted elevated levels of mission capacity but, given that mission and vision represent the rudimentary architecture for any nonprofit, this result was not very surprising, and further reinforces mission as the central capacity area for nonprofit operations. In addition, Table 3

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

Organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour ...

51

Table 3: Difference of means tests results

Mean s.d. Mean s.d. Entrepreneurial group Less entrepreneurial group Significance Mean 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press 10 11 Mission and vision Strategy and planning Programme design and evaluation Human resources Top management team leadership Information technology Financial management Financial systems and position Fund development Board leadership Marketing, communications and external relations 3.0 2.4 2.5 2.3 3.0 2.5 2.6 2.3 2.0 2.2 2.3 s.d. 0.40 0.44 0.48 0.51 0.32 0.56 0.65 0.48 0.41 0.54 0.42 Mean 2.9 2.2 2.4 2.1 2.5 2.0 2.1 1.8 1.7 2.1 2.1 s.d. 0.57 0.52 0.50 0.60 0.56 0.68 0.65 0.72 0.40 0.44 0.44 *** *** ** ** ***

Notes: ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

shows several capacity areas where the two groups did not differ significantly. One noteworthy area was Marketing, Communications and External Relations. Zietlow (2001), for example, suggests that entrepreneurial nonprofits ought to have greater marketing capacity to succeed, and Shaw (2004) uses the term entrepreneurial marketing to describe the special properties of marketing in entrepreneurial agencies. Moreover, several scholars have proposed that the ability to generate and sustain a network of relationships represents a major capacity area for social entrepreneurs (Mair and Marti, 2006). Still, this research did not find any considerable difference between entrepreneurial and less entrepreneurial organisations in terms of marketing or external relations capacity. One dimension to take into account is that most of the sample agencies could be described as donative, that is, a majority of their revenue comes from philanthropic funds, which raises the question as to whether the situation looks different in commercial nonprofits. Also, in their typology of social entrepreneurs, Zahra et al (2009) argue that entrepreneurial action can substantially vary in size and scope.This raises the question as to whether marketing and relational capacity will be more crucial for those seeking radical change on a large scale compared to those who primarily seek less radical ends in order to address regional or local issues. Clearly these are topics for future research.

Financial capacity

As mentioned previously, the entrepreneurial group on average consisted of relatively larger agencies with larger annual revenues. Moving into the areas where the two groups showed significant differences, the divergence in financially related capacity

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

52

Fredrik O. Andersson

became obvious. First, entrepreneurial agencies had stronger financial management capacity, that is, greater capacity to generate updated and integrated financial plans, and maintain formal internal controls to govern track and report on their financial operations. Second, entrepreneurial agencies also enjoyed a stronger financial position compared to less entrepreneurial organisations. A closer analysis of the individual capacity elements in this cluster revealed that in terms of cash flow and dependency on philanthropic revenue, the differences between the two groups were minor. Instead, the key difference was found in the bottom line.While entrepreneurial organisations frequently operated in the black, less entrepreneurial agencies seldom showed positive operating margins.This may, in part, be related to the differences in fund development capacity. Even though both groups showed room for capacity improvement in this area, the apparent divergence captured that entrepreneurial nonprofits had more fundraising competence as well as greater planning implementation capacity in the fund development process. Finally, the discrepancy in information technology capacity further reinforced many of the above dimensions as the information technology capacity cluster primarily captures internal technological infrastructures and staff communication efficiency, for example, access and use of electronic databases, reporting and tracking systems for clients, staff and volunteers, and systems for tracking financial outcomes and processes. Taken together, financial position matters but entrepreneurial agencies also seem to bring complementary financial competence. The notion that access to financial resources is important in the entrepreneurial processes is far from new (Gnyawali and Fogel, 1994) but it is equally important how these resources are configured (Brush et al, 2001). Understanding how organisations make do with resources they have has produced interesting insights into how entrepreneurial agents move forward despite serious resource constraints, what Baker and Nelson (2005: 333) refer to as bricolage or making do by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities. Future research is needed to establish whether, for example, financial management represents one of these so-called bricolage capabilities (see Baker and Nelson, 2005: 357), that is, the ability to skilfully employ bricolage, associated with NPE. As mentioned earlier, this research cannot determine whether entrepreneurial behaviour is the cause or effect of financial capacity. However, from a practitioner perspective it appears that funding alone is not enough to stimulate entrepreneurial behaviour in nonprofits. Foundations and other donors may therefore be advised to combine funding with financial capacity-building efforts to create a supportive infrastructure from which entrepreneurial opportunities can be pursued. The differences in age and size between the two groups also suggest that an organisations evolution and current life stage play a role in its entrepreneurial profile. Hence, the idea of a one-size-fits-all approach or narrowly defined entrepreneurial best practices are unlikely to be relevant or successful. Instead, efforts to diagnose and assess both organisational capacity and life stage would help funders build a more solid foundation for fuelling entrepreneurial behaviours in nonprofits.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

Organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour ...

53

Top management leadership capacity

Next to mission and vision, the strongest capacity element associated with entrepreneurial agencies resides in the top management team. From a capacity building viewpoint, building strong management teams has long been part of scaling strategies in entrepreneurial ventures, and the role of management capacity is also prominent in relation to creating high-performing nonprofits (see Letts et al, 1997). In entrepreneurship research, scholars make use of upper echelons theory (Hambrick, 2007) to describe how the characteristics of the top management team function as filters in an agencys strategic and decision-making processes. Given the complexity of entrepreneurial processes, these filters generate variation in terms of capacity as well as outcomes as the bundle of top management characteristics is typically unique for each organisation. Put differently, the upper echelons perspective stresses that human competence will serve as a lever for other organisational resources in the pursuit of certain ends. Hence, the variance in top management team capacity between the two groups indicate that clues for building entrepreneurial capacity in nonprofits may be found by exploring the team dynamics, leadership, team demographics and judgement of the dominant coalition in agencies. Interestingly, the difference in board leadership capacity is insignificant between the two groups. This stands in contrast to Morris et als (2007) finding that board capacity is positively related to nonprofit entrepreneurial behaviour. However, in a qualitative study by Helm and Renz (2008), the entrepreneurial function of nonprofit organisations was predominantly found at the executive leadership level, with boards having more of a complementary and supportive role.A third perspective comes from Light (2008), who proposed that entrepreneurial nonprofits might use a different governance mode than their less entrepreneurial peers. What is clear is that governance, leadership and the role of the boardexecutive relationship are very potent areas for future NPE research. Short et al (2009), for example, concluded that the upper echelon perspective could inform both theoretical and practical development of NPE.To date, social entrepreneurship research has paid little attention to the role of teams and governance in understanding NPE. In part, this absence exists because attention is commonly drawn towards individuals rather than groups and organisational functions in social entrepreneurship scholarship (Light, 2008). These results suggest that the role of human agency in NPE cannot be underestimated, and that competence-based organisational capacity differentiates entrepreneurial and less entrepreneurial nonprofits more than do more tangible aspects such as strategic plans and/or marketing plans. In addition, even if boards have little direct impact on NPE, the relational dynamics between the board of directors, top management and other stakeholders appear to be of significance for NPE research (Helm and Renz, 2008). Furthermore, linking NPE to governance implicitly must take into consideration the role of the board in the value-protecting and value-creating processes of nonprofit agencies.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

54

Fredrik O. Andersson

Conclusion

To position and clarify the meaning of entrepreneurship in organisations, Flamholtz (1986) described entrepreneurial activities as the offence and managerial activities as the defence of an agency. Today there are several foundations, philanthropists, policy makers, managers and boards that seek to build or rebuild nonprofit offensive abilities and, while it is too early to provide any recommendations for how and exactly what capacities are needed to establish such abilities, this paper has proposed that one way forward is to examine the overlap between NPE behaviours and organisational capacity. By contrasting capacity sets associated with entrepreneurial and less entrepreneurial nonprofit agencies, academics and policy makers can begin to build a more rigorous understanding of entrepreneurial capacities in pursuit of normative hypotheses and programmes. Such advances will also enable a growing conception of the determinants of NPE and help bring legitimacy to the NPE field.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

References Baker, T. and Nelson, R. (2005) Creating something from nothing: resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage, Administrative Science Quarterly, 50: 32966. Boschee, J. (2006) Migrating from innovation to entrepreneurship: How nonprofits are moving toward sustainability and self-sufficiency, Minneapolis, MN: Encore! Press. Brinckerhoff, P. (2000) Social entrepreneurship:The art of mission-based venture development, New York, NY: Wiley. Brush, C., Greene, P. and Hart, M. (2001) From initial idea to unique advantage: the entrepreneurial challenge of constructing a resource base, Academy of Management Executive, 15 (1): 6478. Cairns, B. Harris, M. and Young, P. (2005) Building the capacity of the voluntary nonprofit sector: challenges of theory and practice, International Journal of Public Administration, 28: 86985. Covin, J., Green, K. and Slevin, D. (2006) Strategic process effects on the entrepreneurial orientationsales growth rate relationships, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30: 5781. Dart, R. (2004) The legitimacy of social enterprise, Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14 (4): 41124. Dees, J., Emerson, J. and Economy, P. (eds) (2001) Enterprising nonprofits: A toolkit for social entrepreneurs, New York, NY: Wiley. Eikenberry, A. and Kluver, J. (2004) The marketization of the nonprofit sector: civil society at risk?, Public Administration Review, 64 (2): 13240. Flamholtz, E. (1986) How to make the transition from an entrepreneurship to a professionally managed firm, San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Gnyawali, D. and Fogel, D. (1994) Environments for entrepreneurship development: key dimensions and research implications, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18 (4): 4362.

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

Organisational capacity and entrepreneurial behaviour ...

55

Guthrie, K. and Preston, A. (2005) Building capacity while assessing it:Three foundations experiences using the McKinsey capacity assessment grid, San Francisco, CA: Blueprint Research & Design. Hambrick, D. (2007) Upper echelons theory: an update, Academy of Management Review, 32: 33443. Helm, S. and Andersson, F.O. (2010) Beyond taxonomy: an empirical validation of social entrepreneurship in the nonprofit sector, Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 20 (3): 25976. Helm, S. and Renz, D. (2008) Boards, governance, and social entrepreneurship: an emerging framework, Paper presented at the annual conference of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action, Philadelphia, PA, 2022 November. Hill, T., Kothari, T. and Shea, M. (2010) Patterns of meaning in the social entrepreneurship literature: a research platform, Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1 (1): 531. Kistruck, G. and Beamish, P. (2010) The interplay of form, structure and embeddedness in social entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34 (4): 73561. Letts, C., Ryan, W. and Grossman, A. (1997) Virtuous capital: what foundations can learn from venture capitalists, Harvard Business Review, 75 (2): 3644. Light, P. (2008) The search for social entrepreneurship, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Light, P. and Hubbard, E. (2004) The capacity building challenge: a research perspective, in P. Patrizi, K. Sherwood and A. Spector (eds) The capacity building challenge: Practice matters:The improving philanthropy project, Philadelphia, PA and New York, NY: The OMG Center for Collaborative Learning and The Foundation Center. McDonald, R. (2007) An investigation of innovation in nonprofit organizations: the role of organizational mission, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 6 (2): 25681. Mair, J. and Marti, I. (2006) Social entrepreneurship research: a source of explanation, prediction, and delight, Journal of World Business, 41: 3644. Morris, M. and Joyce, M. (1998) On the measurement of entrepreneurial behavior in not-for-profit organizations: implications for social marketing, Social Marketing Quarterly, 12 (2): 93104. Morris, M., Coombes, S., Schindeutte, M. and Allen, J. (2007) Antecedents and outcomes of entrepreneurial and market orientations in a non-profit context: theoretical and empirical insights, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13 (4): 1239. Mort, G.,Weerawardena, J. and Carnegie, K. (2003) Social entrepreneurship: towards conceptualization, International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8 (1): 7688. Pearce, J., Fritz, D. and Davis, P. (2010) Entrepreneurial orientation and the performance of religious congregation as predicted by rational choice theory, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34 (1): 21948. Peter, J. (1979) Reliability: a review of psychometric basics and recent marketing practices, Journal of Marketing Research, 16: 617.

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

56

Fredrik O. Andersson

Rauch,A.,Wiklund, J., Lumkin, G.T. and Frese, M. (2009) Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: an assessment of past research and suggestions for the future, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33: 76187. Sadler, R. (2000) Corporate entrepreneurship in the public sector: the dance of the chameleon, Australian Journal of Public Administration, 59 (2): 2543. Shaw, E. (2004) Marketing in the social enterprise context: is it entrepreneurial?, Qualitative Market Research, 7 (3): 194205. Short, J., Moss,T. and Lumpkin, G.T. (2009) Research in social entrepreneurship: past contributions and future opportunities, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3: 16194. Sorescu, A., Chandy, R. and Prabhu, J. (2003) Sources and financial consequences of radical innovation: insights from pharmaceuticals, Journal of Marketing, 67: 82102. Stevens, S.K. (2001) Nonprofit lifecycles: stage-based wisdom for nonprofit capacity,Wayzata, MN: Stagewise Enterprises. Stevenson, H. and Jarillo, J. (1990) A paradigm of entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial management, Strategic Management Journal, 11: 1727. Strichman, N., Bickel, W. and Marshood, F. (2008) Adaptive capacity in Israeli social change nonprofits, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37 (2): 22448. Voss, Z.,Voss, G. and Moorman, C. (2005) An empirical examination of the complex relationships between entrepreneurial orientation and stakeholder support, European Journal of Marketing, 39 (9/10): 113250. VPP (Venture Philanthropy Partners) (2001) Effective capacity building in nonprofit organizations, Prepared for VPP by McKinsey & Company, Washington, DC:VPP. Weerawardena, J. and Mort, G. (2006) Investigating social entrepreneurship: a multidimensional model, Journal of World Business, 41: 2135. Wiklund, J. and Shepherd, D. (2005) Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach, Journal of Business Venturing, 20: 7191. Zahra, S., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. and Shulman, J. (2009) Typology of social entrepreneurs: motives, search processes and ethical challenges, Journal of Business Venturing, 24: 51932. Zietlow, J. (2001) Social entrepreneurship: managerial, financial and marketing aspects, Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 9 (1/2): 1944.

Fredrik O. Andersson, Midwest Center for Nonprofit Leadership and the Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Bloch School of Management, University of Missouri-Kansas City, USA fredrik.andersson@umkc.edu

Delivered by Ingenta to: Lia Levin IP : 132.66.7.212 On: Tue, 05 Apr 2011 06:49:08 Copyright The Policy Press

Voluntary Sector Review vol 2 no 1 2011 4356 10.1332/204080511X560611

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Harmonizing A MelodyDocument6 pagesHarmonizing A MelodyJane100% (1)

- House & Garden - November 2015 AUDocument228 pagesHouse & Garden - November 2015 AUHussain Elarabi100% (3)

- FS2 Learning Experience 1Document11 pagesFS2 Learning Experience 1Jona May BastidaNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud QuotesDocument7 pagesSigmund Freud Quotesarbeta100% (2)

- Swedenborg's Formative Influences: Jewish Mysticism, Christian Cabala and PietismDocument9 pagesSwedenborg's Formative Influences: Jewish Mysticism, Christian Cabala and PietismPorfirio MoriNo ratings yet

- DODAR Analyse DiagramDocument2 pagesDODAR Analyse DiagramDavidNo ratings yet

- Does social media improve or impede communicationDocument3 pagesDoes social media improve or impede communicationUmar SaleemNo ratings yet

- Decision Support System for Online ScholarshipDocument3 pagesDecision Support System for Online ScholarshipRONALD RIVERANo ratings yet

- Dyson Case StudyDocument4 pagesDyson Case Studyolga100% (3)

- Disability Election ManifestoDocument2 pagesDisability Election ManifestoDisability Rights AllianceNo ratings yet

- Lcolegario Chapter 5Document15 pagesLcolegario Chapter 5Leezl Campoamor OlegarioNo ratings yet

- Readers TheatreDocument7 pagesReaders TheatreLIDYANo ratings yet

- Brochure Financial Planning Banking & Investment Management 1Document15 pagesBrochure Financial Planning Banking & Investment Management 1AF RajeshNo ratings yet

- Transportation ProblemDocument12 pagesTransportation ProblemSourav SahaNo ratings yet

- Preterm Labour: Muhammad Hanif Final Year MBBSDocument32 pagesPreterm Labour: Muhammad Hanif Final Year MBBSArslan HassanNo ratings yet

- Present Tense Simple (Exercises) : Do They Phone Their Friends?Document6 pagesPresent Tense Simple (Exercises) : Do They Phone Their Friends?Daniela DandeaNo ratings yet

- A COIN FOR A BETTER WILDLIFEDocument8 pagesA COIN FOR A BETTER WILDLIFEDragomir DanielNo ratings yet

- Government of Telangana Office of The Director of Public Health and Family WelfareDocument14 pagesGovernment of Telangana Office of The Director of Public Health and Family WelfareSidhu SidhNo ratings yet

- Frendx: Mara IDocument56 pagesFrendx: Mara IKasi XswlNo ratings yet

- EB - Lecture 2 - ECommerce Revenue Models - HDocument8 pagesEB - Lecture 2 - ECommerce Revenue Models - HXolani MpilaNo ratings yet

- Career Guidance Program Modules MonitoringDocument7 pagesCareer Guidance Program Modules MonitoringJevin GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Robots Template 16x9Document13 pagesRobots Template 16x9Danika Kaye GornesNo ratings yet

- Intro to Financial Management Chapter 1 SummaryDocument11 pagesIntro to Financial Management Chapter 1 SummaryweeeeeshNo ratings yet

- Summer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterDocument6 pagesSummer 2011 Redwood Coast Land Conservancy NewsletterRedwood Coast Land ConservancyNo ratings yet

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocument6 pagesDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 Private Hospitals in Bagalkot DistrictDocument30 pagesCOVID 19 Private Hospitals in Bagalkot DistrictNaveen TextilesNo ratings yet

- Biomass Characterization Course Provides Overview of Biomass Energy SourcesDocument9 pagesBiomass Characterization Course Provides Overview of Biomass Energy SourcesAna Elisa AchilesNo ratings yet

- Simptww S-1105Document3 pagesSimptww S-1105Vijay RajaindranNo ratings yet

- Second Year Memo DownloadDocument2 pagesSecond Year Memo DownloadMudiraj gari AbbaiNo ratings yet

- 01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsDocument11 pages01.09 Create EA For Binary OptionsEnrique BlancoNo ratings yet