Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Causes Fluid Overloa1

Uploaded by

Norine_Barrios_2887Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Causes Fluid Overloa1

Uploaded by

Norine_Barrios_2887Copyright:

Available Formats

What causes fluid overload?

The main cause of fluid overload is heart failure (also called congestive heart failure), a condition in which the heart is weakened and can't circulate enough blood to the body's other organs. When the flow of blood out of the heart slows, fluid builds-up in the body's tissues and the kidneys aren't able to get rid of the excess sodium (salt) and water. Excess fluid can build up in various locations in the body, leading to swelling in the feet, ankles and lower legs (peripheral edema) and/or swelling in the abdomen (ascites). When excess fluid collects in the lungs, the condition is called pulmonary edema. Signs and Symptoms of Fluid Overload

Common warning signs and symptoms of fluid overload include: y y y y y y Edema (swelling in the feet, ankles or lower legs) Ascites (swelling in the abdomen) Rapid increase in body weight due to fluid buildup Tiredness Difficulty breathing Coughing and/or trouble breathing at night (especially when lying flat)

Fluid overload can also occur as a result of some other health conditions, including kidney disease and liver disease. It can also be a side effect of some medications. According to the National Institutes of Health, almost 5 million people in the United States have heart failure, the foremost cause of fluid overload. Each year, about 550,000 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed. While the condition can develop in people of all ages, heart failure is more common among the elderly. Medicare data shows that heart failure is the most common diagnosis among elderly people who are hospitalized. And because the American population is aging, the number of people diagnosed with heart failure is increasing every year. Heart failure is also more common among people who are overweight or obese. Excess weight puts a greater strain on the heart. It also can lead to type 2 diabetes, which adds to the risk of heart failure. To learn more about ultrafiltration and heart failure, take a look at the links on the next page.

Ultrafiltration is a medical therapy that removes excess salt and water from the bodies of patients who have a condition called fluid overload. In this procedure, which uses a small, portable machine, the patient's blood is passed through a filter that removes the excess fluid from the blood. The filtered blood -- free of the excess fluid -- is then returned to the patient.

With ultrafiltration, the rate of fluid removal is adjustable, so doctors can gradually remove the excess fluid without upsetting blood pressure, heart rate or electrolyte balance (chemical substances like sodium, potassium and chloride). Up to 500 milliliters, or 1.1 pound, of fluid can be safely removed per hour. The average removal rate is 250 milliliters, or about a half pound, an hour, and treatment usually lasts about 24 hours. In general, people receiving ultrafiltration therapy stay in the hospital for three to four days. This therapy can be used in combination with or as an alternative to diuretics (drugs that help rid the body of excess water), inotropic drugs (medicines that stimulate the heart to expel more blood with each beat) or vasodilator drugs (medicines that widen blood vessels) to achieve the target fluid removal goal for the patient. And, because it removes sodium and resets body fluid levels, ultrafiltration may also improve the effectiveness of oral diuretics ("water pills") that patients take on an ongoing basis. A clinical study called "Ultrafiltration vs Intravenous Diuretics for Patients Hospitalized for Acute Decompensated Congestive Heart Failure" (UNLOAD) compared the safety and efficacy of ultrafiltration treatment with diuretics given intravenously (that is, with a needle into the bloodstream) to treat fluid overload in heart failure patients. Results of the UNLOAD study showed that ultrafiltration not only removed more fluid than intravenous diuretics, but far fewer patients who received ultrafiltration had to return to the hospital, emergency room or clinic for worsening heart failure. Compared to traditional dialysis equipment, the device used in ultrafiltration therapy needs only a small amount of blood (33 milliliters, or 2.5 tablespoons) from one of the patient's peripheral veins (like one in an arm). It is highly automated and can be operated by nonspecialized health care professionals in diverse locations in and outside the hospital. In contrast, dialysis is used on patients suffering from kidney (renal) failure. Dialysis requires large amounts of blood (200-300 milliliters -- 20 tablespoons or more) and central venous access (that is, use of one of the deeper veins of the chest, neck or groin that leads directly to the heart). Plus, dialysis equipment must be operated by specialized dialysis health care professionals in intensive care settings in a hospital or clinic.

Fluid Overload

This article refers to fluid overload that occurs when the circulating volume is excessive, i.e. more than the heart can effectively cope with. This results in heart failure, which usually manifests as pulmonary oedema and peripheral oedema.

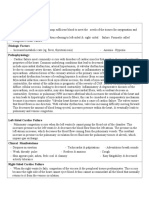

Causes

y Iatrogenic - excessive intravenous fluids, blood transfusions: o The risk of fluid overload is higher in elderly patients and if there is cardiac or renal impairment, sepsis, major injury or major surgery. o There may be insufficient training of junior doctors regarding intravenous fluid therapy. Postoperative patients may receive inappropriately large amounts of intravenous fluid and/or sodium.1

y y y y

Heart failure Renal failure - depending on severity and whether oliguric or not. Increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion, e.g. following head injury or major surgery. Responses to physiological stress: o Excretion o0066 excess sodium and water is more difficult for injured or surgical patients (owing to various physiological responses to injury and surgery which affect renal function and fluid balance regulation).1 o It is now recognised that there are complex interactions between heart, lung and kidneys which affect body fluid and sodium regulation. When one of these organs is stressed it may affect the functioning of the others and impact on fluid balance.2,3,4

Physiology1

The recommended intake of sodium and water for normal adults is: y y Sodium 70 mmol/24 hours Water 1.5 to 2.5 litres (25 to 35 mL/kg/24 hours)

In normal subjects the extracellular fluid sodium concentration and osmolality are maintained by the kidneys: y y y Osmoreceptors and changes in vasopressin secretion affect urinary concentration and water excretion. If there is sodium depletion, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated with consequent reduction in urinary sodium. However, the body's response to sodium excess is sluggish and even normal subjects are slow to excrete an excess sodium load.

For hospitalised patients requiring fluid therapy, be aware that: y y There are pros and cons of crystalloid and colloid solutions. So-called "normal saline" (0.9% sodium chloride) actually contains supranormal amounts of sodium chloride (154 mmol/L sodium and chloride compared with the physiological 140 mmol/L for sodium and 95 mmol/L for chloride). Several studies have demonstrated that even healthy subjects find it difficult to excrete solutions with a high chloride content (in comparison with solutions such as Hartmann's). Excretion of excess sodium and water is more difficult for injured or surgical patients.

Presentation

y y Acutely, fluid overload usually presents as acute pulmonary oedema with symptoms of acute dyspnoea. See separate article Acute Pulmonary Oedema. Chronic fluid overload (in the context of intravascular fluid overload) usually presents with features of chronic heart failure; the main symptoms are fatigue, dyspnoea and pitting oedema. For details see separate article Heart Failure Diagnosis and Investigation.

Differential diagnosis

Other causes of dyspnoea (see separate article on Breathlessness): y y Pneumonia. Bronchospasm, e.g. asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

y y y y

Pulmonary embolism (classically with no added lung sounds). Acute anaphylaxis may cause wheezing (may have swollen lips or tongue). Fibrosing alveolitis also causes fine inspiratory crackles (longstanding symptoms usually). Poor inspiratory effort may cause basal lung crackles - resolves after a few deep breaths.

Other causes of raised jugular venous pressure (JVP): y y y Pulmonary embolism. Constrictive pericarditis or cardiac tamponade cause raised JVP - which unlike normal JVP will INCREASE on inspiration. Superior vena cava obstruction (distention of neck and upper limb veins, classically nonpulsatile).

Other causes of peripheral oedema: y y y y y Pre-eclampsia (always check urine protein if >20 weeks pregnant and unwell/oedema). Hypoproteinaemia - nephrotic syndrome, malnutrition, malabsorption or liver disease. Lymphoedema (classically non-pitting oedema). Hypothyroidism. Venous obstruction (may be unilateral) due to: o Deep venous thrombosis (DVT). o Severe varicose veins. o Pelvic mass (including pregnancy). o Inferior vena cava obstruction (unlikely to redistribute with posture).

Other causes of ascites, e.g. cirrhosis, portal hypertension and malignancy.

Investigations

Note: if the patient is distressed with acute pulmonary oedema, start treatment before investigations. Initial investigations which will help make a diagnosis in most cases: y y y y y y ECG - cardiac arrhythmias, infarction or hypertrophy. Chest X-Ray - may identify pulmonary oedema, looks for other chest pathology, e.g. pneumonia. Serum urea, creatinine and electrolytes - for renal function; to check if electrolyte imbalance contributing to problems. Full blood count - for anaemia and features of infection. Liver function tests - albumin and protein levels. Bedside echocardiography for a sick patient may help identify the cause of cardiac dysfunction, e.g. ventricular failure, cardiac tamponade or large pulmonary embolus.

Other possible investigations: y y y y Arterial blood gases - for ill patients or if cause of dyspnoea unclear. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and echocardiography help diagnose heart failure. Fluid balance charts and serial weights for monitoring response to treatment. Further investigations if necessary according to suspected cause.

Management

See separate Acute Pulmonary Oedema article (for acute symptoms) and Heart Failure Management article (for chronic symptoms).

Prevention

y y y y y Optimise treatment of heart failure and renal failure. Be aware that caution is needed with intravenous fluid replacement, including blood transfusion. For surgical patients, guidelines on appropriate postoperative fluid replacement are now available.1 For patients with severe sepsis or septic shock, Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines include details of appropriate fluid therapy.5 Bedside assessment of postoperative patients with oliguria:1 o In the absence of complications, oliguria occurring soon after operation is usually a normal physiological response to surgery. o However, at the bedside a falling urine output may be interpreted as indicating hypovolaemia and patients may be given too much sodium-containing fluid. o The key question is whether or not the oliguric patient has significant intravascular hypovolaemia which needs treatment - this can often be assessed clinically using signs such as capillary refill, jugular (central) venous pressure, and the trend in pulse and blood pressure. Interpret the urine output according to these clinical signs and the normal effects of surgery on urine output.

You might also like

- Portal Hypertension, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandPortal Hypertension, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Hemodialysis Removes Wastes and Fluids From BloodDocument23 pagesHemodialysis Removes Wastes and Fluids From BloodAvinder MannNo ratings yet

- Case Study PPT Patho NLNGDocument36 pagesCase Study PPT Patho NLNGKate ChavezNo ratings yet

- Hypovolemic Shock 09Document58 pagesHypovolemic Shock 09Joanne Bernadette Aguilar100% (2)

- Fluid Excess Diagnostic TestsDocument5 pagesFluid Excess Diagnostic TestsQueenie Velasquez Reinoso JacksonNo ratings yet

- Medical Diagnosis: Kidney Failure and Fluid Volume ExcessDocument74 pagesMedical Diagnosis: Kidney Failure and Fluid Volume ExcessSheela Khrystyn LeeNo ratings yet

- Brief DescriptionDocument13 pagesBrief DescriptionHerson RamirezNo ratings yet

- Dialysis Types and Processes ExplainedDocument38 pagesDialysis Types and Processes ExplainedNish Macadato BalindongNo ratings yet

- Excrete Less Salt and Water. It Also Produces A Reduction in Renal Plasma Flow andDocument3 pagesExcrete Less Salt and Water. It Also Produces A Reduction in Renal Plasma Flow andCoole PhilipNo ratings yet

- Fluid Deficit RevisedDocument6 pagesFluid Deficit RevisedShaira SariaNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal FailureDocument13 pagesAcute Renal FailureGlorianne Palor100% (2)

- Congestive Heart FailureDocument10 pagesCongestive Heart Failurealex_cariñoNo ratings yet

- Study Guide:: DialysisDocument13 pagesStudy Guide:: DialysisDan Dan ManaoisNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure Case StudyDocument28 pagesHeart Failure Case StudySoror RoseNo ratings yet

- Fluids Electrolytes NotesDocument23 pagesFluids Electrolytes NotesHamza AdriNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal Failure Nursing Care PlanDocument15 pagesAcute Renal Failure Nursing Care PlanRanusha AnushaNo ratings yet

- Dapus 3Document7 pagesDapus 3Dhea NadhilaNo ratings yet

- Case PresDocument6 pagesCase PresCharm TanyaNo ratings yet

- First aid and treatment for hypovolemia from blood lossDocument5 pagesFirst aid and treatment for hypovolemia from blood lossIan Rama100% (1)

- Cardiac Failure & Myocardial Infarction GuideDocument6 pagesCardiac Failure & Myocardial Infarction GuideDaniel GeduquioNo ratings yet

- NCM 106 Acute Biologic CrisisDocument142 pagesNCM 106 Acute Biologic CrisisEllamae Chua88% (8)

- DyalisisDocument24 pagesDyalisisAbdulla Abu EidNo ratings yet

- CARDIAC FAILURE NewDocument60 pagesCARDIAC FAILURE NewJake MillerNo ratings yet

- HemodialysisDocument4 pagesHemodialysisAbdul Hamid NoorNo ratings yet

- Isyncope: Partial or Complete Loss of Consciousness With Interruption of Awareness of Oneself and OnesDocument4 pagesIsyncope: Partial or Complete Loss of Consciousness With Interruption of Awareness of Oneself and OnesLimLichynNo ratings yet

- Medical Surgical Fluid and Electrolytes FVD FVEDocument7 pagesMedical Surgical Fluid and Electrolytes FVD FVEMichaelaKatrinaTrinidadNo ratings yet

- FLUIDS-ELECTROLYTES-GROUP-1-COMPILATIONDocument41 pagesFLUIDS-ELECTROLYTES-GROUP-1-COMPILATIONShaira SariaNo ratings yet

- Kidney FailureDocument2 pagesKidney Failuredanee しNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal FailureDocument25 pagesAcute Renal Failurebkbaljeet116131No ratings yet

- PR ThoraksDocument19 pagesPR ThoraksKevin KarimNo ratings yet

- Complicati On Cause Symptom Management Prevention Patient Related Factors Patient End StrategyDocument12 pagesComplicati On Cause Symptom Management Prevention Patient Related Factors Patient End StrategyChiranjib ChattopadhyayNo ratings yet

- Portal hypertension diagnosis and managementDocument23 pagesPortal hypertension diagnosis and managementSumathi Gopinath100% (1)

- Lots of Salt Causes Retention of WaterDocument8 pagesLots of Salt Causes Retention of WaterMarchant Lowry BleyNo ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrolytes (Acid Base)Document31 pagesFluid and Electrolytes (Acid Base)Diana TahamidNo ratings yet

- Congestive Heart FailureDocument5 pagesCongestive Heart FailureKriztah CarrozNo ratings yet

- Medscape Hypovolemic ShockDocument14 pagesMedscape Hypovolemic ShockSarah Ovinitha100% (1)

- IPDIDocument30 pagesIPDIaris budionoNo ratings yet

- Hemodialysi S: Ariane Jake C. Fernandez, RN, MSNDocument37 pagesHemodialysi S: Ariane Jake C. Fernandez, RN, MSNMicah Alexis Candelario100% (3)

- Nursing Diagnosis Fluid ExcessDocument8 pagesNursing Diagnosis Fluid ExcessLuthfiy IrfanasruddinNo ratings yet

- Fluid N Electrolyte BalanceDocument60 pagesFluid N Electrolyte BalanceAnusha Verghese67% (3)

- Medical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5th Edition Nelms Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesMedical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5th Edition Nelms Solutions Manualsophiechaurfqnz100% (31)

- Medical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5Th Edition Nelms Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument29 pagesMedical Nutrition Therapy A Case Study Approach 5Th Edition Nelms Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFStephanieMckayeqwr100% (7)

- Edema and EffusionsDocument45 pagesEdema and EffusionsMNS 51No ratings yet

- HiponatremiaDocument8 pagesHiponatremiaMeidistya Ayu MardhianiNo ratings yet

- Shock: By: Dr. Samer Sabri M.B.CH.B F.I.C.M.SDocument34 pagesShock: By: Dr. Samer Sabri M.B.CH.B F.I.C.M.Ssamer falconNo ratings yet

- Most of Your Questions Exam Will Be On The Nursing AspectDocument8 pagesMost of Your Questions Exam Will Be On The Nursing AspectLarine WinkleblackNo ratings yet

- Primary AldosteronismDocument31 pagesPrimary AldosteronismSteph100% (1)

- Clinical Symptoms Due To Fluid CongestionDocument6 pagesClinical Symptoms Due To Fluid CongestionedenpearlcastilloNo ratings yet

- Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument17 pagesChronic Kidney DiseaseAdelle SmithNo ratings yet

- Group 11 HeamodialysisDocument4 pagesGroup 11 HeamodialysisElizabeth OforiNo ratings yet

- Hypovolemic SHOCK REPORTDocument14 pagesHypovolemic SHOCK REPORTMae Kailah Dimples AlcontinNo ratings yet

- Alterations in Fluid VolumeDocument4 pagesAlterations in Fluid VolumeRichmund Earl GeronNo ratings yet

- Indications of Dialysis in Acute Renal Failure (ARF)Document3 pagesIndications of Dialysis in Acute Renal Failure (ARF)Tariku GelesheNo ratings yet

- Hemodynamics and Hemostasis Guide to EdemaDocument33 pagesHemodynamics and Hemostasis Guide to EdemaSawera RaheemNo ratings yet

- Clinical Aspect of Heart FailureDocument67 pagesClinical Aspect of Heart FailureAri Bandana TasrifNo ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrolytes Assignment 1. What Are The Different Processes of Body Fluid and Solutes Movement? and Give at Least 2 Examples EachDocument8 pagesFluid and Electrolytes Assignment 1. What Are The Different Processes of Body Fluid and Solutes Movement? and Give at Least 2 Examples EachAngelicaNo ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrolytes Assignment 1. What Are The Different Processes of Body Fluid and Solutes Movement? and Give at Least 2 Examples EachDocument8 pagesFluid and Electrolytes Assignment 1. What Are The Different Processes of Body Fluid and Solutes Movement? and Give at Least 2 Examples EachAngelicaNo ratings yet

- NSG IV Test 3Document4 pagesNSG IV Test 3Maria Phebe SinsayNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsFrom EverandA Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Nur 111 Session 7 Sas 1Document8 pagesNur 111 Session 7 Sas 1Zzimply Tri Sha UmaliNo ratings yet

- l10 Structure, Classification Biosynthesis of ProstaglandinsDocument22 pagesl10 Structure, Classification Biosynthesis of Prostaglandinsbilawal khanNo ratings yet

- Post-Operative CareDocument13 pagesPost-Operative CareFayeann Vedor LoriegaNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Indication Ofelectrohomeopathic MedicinesDocument8 pagesTherapeutic Indication Ofelectrohomeopathic MedicinesMeghanath PandhikondaNo ratings yet

- Abdominal AortaDocument41 pagesAbdominal AortaMichael IdowuNo ratings yet

- Programa de Instrumentacion Quirurgica: Planeamiento Quirurgico Formativa IQX-FT-003-BUCDocument7 pagesPrograma de Instrumentacion Quirurgica: Planeamiento Quirurgico Formativa IQX-FT-003-BUCapi-688140642No ratings yet

- Importance of Venous Congestion For Worsening of Renal Function in Advanced Decompensated Heart FailureDocument8 pagesImportance of Venous Congestion For Worsening of Renal Function in Advanced Decompensated Heart FailureRaul FernandoNo ratings yet

- Chest Physiotherapy ProcedureDocument2 pagesChest Physiotherapy ProcedurePiyali SahaNo ratings yet

- SN02Document11 pagesSN02Enrique San NorbertoNo ratings yet

- What Is A Stroke?: The Type of StrokeDocument14 pagesWhat Is A Stroke?: The Type of Strokediah fitriNo ratings yet

- Fifteen Years Experience With Finger Arterial Pressure MonitoringDocument12 pagesFifteen Years Experience With Finger Arterial Pressure MonitoringLevente BalázsNo ratings yet

- AnaDocument6 pagesAnaMysheb SSNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephritis: Adlyanna VelascoDocument14 pagesAcute Glomerulonephritis: Adlyanna VelascoShaheed SorathiaNo ratings yet

- Acido BaseDocument10 pagesAcido Basebenitez1228No ratings yet

- By: Vismin Prince Magno: Liver CancerDocument17 pagesBy: Vismin Prince Magno: Liver Cancerhedokido100% (1)

- Guidelines for Drug Use in PregnancyDocument22 pagesGuidelines for Drug Use in PregnancyMega SoundNo ratings yet

- Liver TransplantationDocument13 pagesLiver TransplantationSaikat MitraNo ratings yet

- External and Internal Electric Cardiac PacemakersDocument13 pagesExternal and Internal Electric Cardiac PacemakersSerhii SerikovNo ratings yet

- Ncbi Ascorbic AcidDocument7 pagesNcbi Ascorbic AcidOsunlola GabrielNo ratings yet

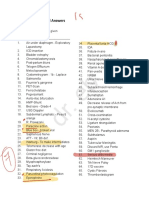

- (198 Total) : NEET-PG 2022 Recall AnswersDocument4 pages(198 Total) : NEET-PG 2022 Recall AnswersAbdul Kalam SheriffNo ratings yet

- Blank 10Document4 pagesBlank 10Pari SharmaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 11Document7 pagesJurnal 11Zella ZakyaNo ratings yet

- LIVERDocument106 pagesLIVERCurt Leye RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Hemorrhagic Stroke: Intracerebral HemorrhageDocument5 pagesHemorrhagic Stroke: Intracerebral HemorrhagesavitageraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Meril InnovationDocument49 pagesIntroduction To Meril InnovationLulu MizbahNo ratings yet

- CardioRenal SyndromeDocument60 pagesCardioRenal Syndromeswaleh breik misfirNo ratings yet

- Sagittal plane of the brain. This appears to be an MRI image.bDocument25 pagesSagittal plane of the brain. This appears to be an MRI image.bjk centralNo ratings yet

- Chest Pain Case PresentationDocument24 pagesChest Pain Case PresentationAnonymous 17awurSUNo ratings yet

- Ritter RulesDocument1 pageRitter RulesSunny NgNo ratings yet

- Digestion and AbsorptionDocument50 pagesDigestion and AbsorptionemeredinNo ratings yet