Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Casa Da Musica and The Question of Form: Harvard GSD Course 3211 - Rafael Moneo On Contemporary Architecture

Uploaded by

Jerry TateOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Casa Da Musica and The Question of Form: Harvard GSD Course 3211 - Rafael Moneo On Contemporary Architecture

Uploaded by

Jerry TateCopyright:

Available Formats

Casa da Musica and the Question of Form

Harvard GSD course 3211 Rafael Moneo On Contemporary Architecture

Jerry Tate MArch II Spring 2007

Introduction

When describing the design process for the Casa da Musica in Porto, Koolhaas explains that the form for the concert hall was previously a scheme for a Dutch house nicknamed the Y2K House. The speed with which this conversion of scale happened is claimed to be two weeks, an almost unbelievably short time to resolve a proposal sufficiently to win against international competition such as Dominique Perrault and Rafael Vinoly.

But what is Koolhaas trying to tell us with this anecdote? The fact that the same form can be used for both a private house and a major concert hall questions the role of form in relation to symbolic as well as functional issues. In fact the form becomes almost arbitrary.

This paper therefore examines the role of the arbitrary in architecture, investigates the Modernist ethos of Functionalism and touches on the role of the arbitrary in the work of Eisenman and Hedjuk, before comparing Koolhaass theoretical stance on Bigness to the design of the Y2K House and the Casa da Musica. The purpose of this is to establish how the role of the arbitrary has informed contemporary design and whether the initial formal strategy for the Porto concert hall was an arbitrary first move or part of a wider design strategy.

Page 1

The arbitrary in architecture

Unfortunately I was not attending Harvard when Rafael Moneo delivered his lecture on the subject of the arbitrary in spring 2006. Moneo identified the first moment of an arbitrary design strategy in architecture as the invention of the Corinthian order, as told by Vitruvius in his Ten Books on Architecture. The story tells us of an offering of a few little things1 placed on the tomb of a maiden, inside of which an acanthus plant sprouted. Noticed by a young artist Callimachus, the novel style and form2 were interpreted and made symmetrical to become the Corinthian order. The key aspect of the arbitrary in this story is that of transference, the style and form of the funeral offering were transferred to become architectural ornament, thereby losing their symbolic and functional associations.

Corinthian capitals, from left to right: The Temple of Minerva at Assisi, The Temple of Vesta at Rome, The Temple of Vesta at Tivoli

The Corinthian order allowed the maximum scope for invention and variation compared to the Doric or Ionic, and became the most popular amongst architects and sculptors for the range of possibilities it offered. Other moments of significant

1

Vitruvius, Marcus. The Ten Books of Architecture, translated by Mick Morgan, Morris (New York: Dover Publications 1960) p. 104. 2 Vitruvius, Marcus. The Ten Books of Architecture, p. 106.

Page 2

invention in architectural history also appear to contain an arbitrary disruption of conventional orders. For example Wolfflin in Renaissance and Baroque identifies the founder of the Baroque as Michelangelo and describes him thus:

Michelangelo is justly called the father of the baroque; this is not because of his eccentricities, since eccentricity cannot be the guiding principle of a style, but because he treated forms with a violence, a terrible seriousness which could only find expression in formlessness. His contemporaries called this quality terribilita.3

At another point of transition in architectural history, Middleton notes that the roots of French Neo-Classicism were inspired by two apparently conflicting sources. The first was the revised translations of Vitruvius by Claude Perrault, and the second was the writings of Michel de Fremin who was probably the first French critic to propose a break with the authority of the orders.4 These opposite critical stances allowed a radical combination of Greek and Gothic styles, producing a new form of Classicism in France.

Moments of inspiration in architecture seem to be associated with a certain type of violent artistic arbitrariness, a destruction of previous orders in order to allow creative expression, which often settles later into a new style.

3

Wolfflin, Heinrich. Renaissance and Baroque, translated by Simon, Kathrin (New York: Cornell University Press 1964) p. 82. 4 Middleton, R. The Abbe de Cordemoy and the Graeco-Gothic Ideal, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, XXV (1962) p. 282.

Page 3

From Modernism to Megastructure

Le Corbusier recommended the use of the plan as generator:

The plan is what determines everything; it is the decisive moment. A plan is not a pretty thing to be drawn, like a Madonna face; it is an austere abstraction; it is nothing more than an algebrization and a dry-looking thing.5

This is more a call for the form of buildings to be derived from the arrangement of their spaces than a purely functionalist statement. Although schemes such as Corbusiers 1927 League of Nations competition entry display a clear programmatic separation, proposals like the 1932 Algiers Project A reveal a more liberated attitude to form.

Le Corbusier and P. Jeanneret League of Nations Palace 1927

Le Corbusier Algiers Project A 1932

Le Corbusier, Charles-Edouard. Towards a New Architecture (New York: Dover Publications 1986, first English translation published in 1931) pp. 48-49.

Page 4

Paramount for Corbusiers theories was that the needs of the interior spaces should determine their exterior expression. In 1923, during a public argument with Auguste Perret about the horizontal window, he wrote a letter to the Paris Journal asserting:

I endeavor to create bright room interiors.that is my main aim, and that is why the appearance of my facades may seem somewhat odd to those who follow the beaten track.6

Sigfried Giedion noted that two major endeavors of modern architecture were achieved at the Gropius designed Bauhaus building in Dessau. The first was a vertical grouping of hovering planes, and the second was the extensive transparency that permits interior and exterior to be seen simultaneously, en face and en profile7 like a Cubist painting. This ambition of the Modern Movement, to eradicate the disjunction between inside and outside, theoretically led to the exterior being determined exactly by the needs of the interior. If this is true, then it follows that at a certain scale, a buildings form should be defined by its internal diagram. The extremes of this logic were explored at the very end of the Modern movement, with the Megastructuralists.

Reichlin, Bruno. The pros and cons of the horizontal window. The Perret Le Corbusier controversy, Daidalos, no. 13 (September 1984) p. 65. 7 Giedion, Siegfried. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition (Cambridge: The Harvard University Press 1941) p. 402.

Page 5

Fumihiko Maki defined the Megastructure in 1964 as a large frame in which all the functions of the city or part of the city are housed8. Megastructuralists envisioned permanent infrastructural frames to house cellular elements of flexible accommodation. Generally their external expression was a direct translation of an internal functional diagram, expressing the permanent or temporary nature of each element. For example Isozakis Spatial Structure or Tanges Plan for Tokyo, visually expressed their organizational design strategy.

Arata Isozaki Spatial Structure 1960

Kenzo Tange Plan for Tokyo 1960

The conceptual limits of this purity in approach soon became clear. Both Cedric Price and Archigram in England began their architectural explorations with Megastructures. Prices 1961 proposal for a Fun Palace in the East End of London was a giant steel structure, topped by a gantry crane in order to rearrange temporary programmatic components. Archigrams Plug-In City was a series of diagonal structures for servicing and circulation, which supported

8

Maki, Fumihiko. Investigations in Collective Form (Washington: Washington University School of Architecture 1964) p. 8.

Page 6

cranes capable of re-arranging the plug-in elements of the city. As Price and Archigram developed their ideas further, the forms of the proposals became less substantial. When Price proposed an alternative Fun Palace for Kentish Town in 1963, the scheme had been reduced to a series of timber framed cubes9. Similarly when Archigram appeared to have the opportunity to build at Monte Carlo in 1970, the architecture had disappeared into the ground to become a grassy bank with trees (in the English tradition etc.) with service outlets at sixmeter intervals.10 The logic of form follows function had led to the function becoming dominant, and somehow the form had evaporated. Isozaki notes in the introduction to Prices last book that the Fun Palace collaborators effectively erased architecture into the system.11

Cedric Price Fun Palace, Lea Valley 1961

Cedric Price Fun Palace. Kentish Town 1963

Price, Cedric. Fun Palace, Camden, London, Architectural Review, volume 139 (November 1967) p. 524. Cook, Peter. Archigram (London: Praeger Publishers 1973) p. 104. 11 Price, Cedric. Isozaki, Arata. Keiller, Patrick. Koolhaas, Rem. Re:CP, ed. Obrist, Hans Ulrich (Switzerland: Birkhauser 2003) p. 35.

10

Page 7

Peter Cook / Archigram Plug-In City 1964

Archigram Monte Carlo - 1970

Page 8

Arbitrariness as a method of escape for Modernism

In the 1970s American architects such as the New York Five and European architects like Aldo Rossi re-examined Modernism to bring the design method out of the paradox into which it had found itself. Rossi believed that historical typologies from the city could present a way of giving more than just functional meaning to form. For architects such as Peter Eisenmann and John Hedjuk it was an autonomous formal investigation which would re-invigorate form generation, coupled with an initial arbitrary first move.

Eisenmans famous series of houses, designed between 1967 and 1975, were generated through a process of logical formal moves, often by starting with an initial grid and using a first impulse, such as rotation or offset, to disrupt the equilibrium of the initial diagram12. After the Cannaregio Town Square project in 1978, this first impulse would be generated by an extraneous force, whether it be Corbusiers Venice Hospital design, an arbitrary line between two bridges or abstract symbols from biology13. Hedjuks series of house designs, starting with the Texas Series House 1 in 1954 and continuing until 1978 with The Cross House, investigated similar strategies. The schemes became more playful as they developed, eventually leaving the initial grid behind entirely to explore the freeform shapes which had first appeared as internal elements for the 1963

Moneo, Rafael. Theoretical Anxiety and Design Strategies in the work of Eight Contemporary Architects (Barcelona: Actar 2004) p. 151. 13 Moneo, Rafael. Theoretical Anxiety and Design Strategies in the work of Eight Contemporary Architects, p. 184.

12

Page 9

Diamond Series: Museum Project C. After the Berlin Masque project of 1980 Hedjuk was to use programmatic narrative to aid him in the generation of his masques.14

Peter Eisenman House III 1969-71

Peter Eisenman Cannaregio Town Square 1978

John Hedjuk - Diamond Series: Museum Project C 1963-67

John Hedjuk Bye House 1972-73

So when Koolhaas founded OMA in 1978 there were already practitioners investigating alternative methods of form generation to the functionalist ethos which had nearly crippled contemporary architectural production.

Hays, K. Michael. Sanctuaries: The Last Works of John Hedjuk (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art 2002) pp. 76-77.

14

Page 10

Koolhaas, Bigness and form

Koolhaass 1978 Delirious New York established a number of precedents for the understanding of exterior and interior space in relation to the contemporary realities of our built environment. Eleven years later three unrealized design projects would develop these ideas into concrete design strategies, the Zeebrugge Sea Terminal, the Tres Grande Bibliotheque and Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie, of which Zeebrugge seemed like an exercise in the use of arbitrary form.

Using Samuel Friedes 1906 Globe Tower as a precedent, Zeebrugge juxtaposed disparate programs of varying speeds and scales within a single iconic envelope. Articles at the time noted that the office used a foam head from a mannequin as a study model.15 We could understand this as an arbitrary first move, the use of a random iconic shape inside which Koolhaas can experiment with internal programmatic overlaps. But the apparently impulsive first move also contains some deeper symbolic implications, especially the use of a head. From the glazed dome at the top of the building hotel guests would have been able to look out over the North Sea, so the building becomes a panopticon with a panoramic screen instead of a central observation post16. The final form of the building therefore implies a gaze towards the ocean, similar to the colossal statues that

Fisher, Thomas. Rem Koolhaas and the Office of Metropolitan Architecture explore the arbitrariness of form in these three recent projects, Progressive Architecture, vol. 71, no. 4 (April 1990) p. 123. 16 Brande, Dirk van de. Maeseneer, Martine de. Rem Koolhaas: Sea trade centre at Zeebrugge: a working Babel, Architectural Design, vol. 62, no. 7-8 (July-Aug 1992) p. 17.

15

Page 11

once guarded the harbors of ancient Greece. It is however sufficiently abstracted that a multitude of other associations can be made, from a hot air balloon (implying movement) to a boulder (a natural coastal feature)17.

Samuel Friede Globe Tower 1906

Koolhaas / OMA Zeebrugge Sea Terminal 1989

Writing for Progressive Architecture in 1990, Thomas Fischer observed of this project that:

Previously we have felt compelled to justify the shape and arrangements of space within our buildings. Koolhaas challenges that compulsion.18

Koolhaass 1995 essay Bigness or the problem of Large synthesized much of these previous investigations into a theoretical approach to the design of Big

Brande, Dirk van de. Maeseneer, Martine de. Rem Koolhaas: Sea trade centre at Zeebrugge: a working Babel, Architectural Design, vol. 62, no. 7-8 (July-Aug 1992) p. 15. 18 Fisher, Thomas. Rem Koolhaas and the Office of Metropolitan Architecture explore the arbitrariness of form in these three recent projects, Progressive Architecture, vol. 71, no. 4 (April 1990) p. 125.

17

Page 12

Buildings and form. The essay is a combination of projective strategies and reflective observations on the contemporary vernacular of the Big, derived from Koolhaass Delirious New York, his design experience in large scale buildings and his observations of the work of John Portman in Atlanta.

He establishes five key point of Bigness in the essay. Point three is particularly interesting when trying to understand his attitude towards the generation of form as he asserts that in a Big Building:

Interior and exterior architecture become separate projects, one dealing with the instability of programmatic and iconographic needs, the other agent of disinformation offering the city the apparent stability of an object.19

This is a clear break from the resolution of the interior and exterior which had been a project of mainstream Modernism. Freed from a requirement to directly represent the configuration and requirements of the internal arrangement, external form could now pursue other aims towards iconographic or urban identity.

19

Koolhaas, Rem. S, M, L, XL (New York: The Monacelli Press 1995) p. 501.

Page 13

The Y2K House and the Casa da Musica

Koolhaas describes the process of generating a concert hall from a private house almost like a cell division.20 The story of this design development is striking in that the pain of resolving one scheme appeared to relieve the difficulties in generating another.

The clients requirements for the Y2K House were threefold, that it should avoid mess, that it should not be occupied until the year 2000 (hence the name) and that the house should be organized so the family could all come together, but also a place where they could all live separately.21 There were four key phases to the initial designs. The first iteration was a tunnel-like volume with extraneous spaces expressed as separate elements extending from the central form. Believing that the scheme was too reminiscent of other architects work, in the second iteration OMA tried to resolve the extra spaces into a single rectangular form. In the third iteration they followed exactly the required program for all the secondary spaces and wrapped a skin around them. The final and fourth iteration imagined this form as a solid storage volume, from which the main occupied spaces were removed as void. The first iterations then of the Y2K House were generated using a technique of marrying program and form, not unlike Corbusiers plan as generator. The contemporary strategy was introduced

20 Koolhaas, Rem. Transformations, A + U: Architecture and Urbanism, special issue no. 5 (May 2000) p.107. 21 Koolhaas, Rem. Transformations, A + U: Architecture and Urbanism, p. 107.

Page 14

in the fourth iteration, with the creation of voids from a solid form, a method originally used on the Tres Grande Bibliotheque eleven years earlier.

Koolhaas / OMA Y2K House 1999 From left to right, iterations 1, 2, 3 and 4

Koolhaas / OMA Y2K House 1999 Void strategy

A truly radical design move, following Koolhaass dismissal of the Y2K client, was transferring the form developed for the house to the Casa da Musica. Other than the common requirement for a large rectangular space, this transference seems as arbitrary as the development of the Corinthian order from a funeral wreath. But just as Callimachus interpreted the arrangement on the maidens tomb to make it symmetrical, Koolhaas and OMA worked on the given form extensively. The city and site diagrams at the competition stage demonstrate an ambition to promote both urban continuity and contrast through a series of alignments, and the circulation and construction diagrams show how the given form was worked

Page 15

to mould it into a concert hall. Koolhaas describes the moment of transition from house to concert hall:

Of course the house had to be considerably enlarged, but I think the concept gained a lot in terms of credibility.22

This is a very interesting statement as it reveals how Koolhaas considers the status of the design. He perceives it as an abstract formal and spatial strategy, which can be manipulated to any given program. Perhaps this is key to understanding how he can use an identical design technique for both a private house and a public concert hall.

Koolhaas / OMA Casa da Musica 1999 Competition Entry - Site Plan and Urban Diagram

22

Koolhaas, Rem. Transformations, A + U: Architecture and Urbanism, p. 112.

Page 16

Koolhaas / OMA Casa da Musica 1999 Competition Entry - Circulation and Construction Diagrams

When we consider the completed building it still appears willfully alien to the site. The first photograph in the 2004 book Content represents the building as a strange object rising from the slightly dilapidated adjacent housing. Details such as the abrupt way the facade meets the ground, or the unfolded entrance stairway, reinforce its image as a spaceship, temporarily residing at Porto. Even the clearing of the surrounding plaza, accommodating all the parking and servicing beneath, creates a separation from the urban context. But for all this the site plan shows a certain sensitivity in the building form to the surrounding street pattern, and the detail plans reveal an intricate arrangement of relationships and external views through the manipulation of form and space. Perhaps the most challenging aspect of the design process was the resolution of the internal configuration, as the previously solid storage areas in the Y2K House became the occupied ancillary and foyer spaces.

Page 17

Koolhaas / OMA Casa da Musica 2005 Photograph in Content, photograph of entrance

Koolhaas / OMA Casa da Musica 2005 Site Plan and Fourth Floor Plan

Therefore the building fulfills many of the key aspects of Bigness which Koolhaas had described in 1995, a form not wholly determined by internal arrangements or urban context but envisioned as an object with heroic impact. This autonomous attitude to form is tempered somewhat by the incredible skill and subtlety with which the final project is realized.

Page 18

Conclusion

Perhaps the transformation of a form designed for a private house into a concert hall is not as arbitrary as it might appear. Even if it was an initial random move, the logic with which the scheme was subsequently developed renders any judgment on the first formal move extremely difficult.

We are left with two alternatives as to how Koolhaas generated the design for the Casa da Musica. Either he employed the technique developed by Eisenman and Hedjuk to escape the Functionalist ethos, an initial impulse followed by a series of formal manouvres; or the design for the Y2K House can be seen as a spatial strategy prototype, able to be utilized for a variety of different programs and scales. The inclusion of the Universal Modernization Patents in Content implies that Koolhaas would like us to believe that he is developing prototypical strategies, capable of being deployed on a number of projects. There is a comment in the margins of S,M,L,XL which may clarify this approach further:

I think everything now is so indeterminate that it is an illusion to believe you have a theory. So Ive tried to devise formulae that could combine architectural specificity with programmatic instability. I think this is terribly important to do.23

23

Koolhaas, Rem. S, M, L, XL (New York: The Monacelli Press 1995) p. 556.

Page 19

Koolhaas / OMA Content 2004 Universal Modernization Patents

On the one hand the formal strategy for the Casa da Musica seems arbitrary, and on the other it appears to fit Koolhaass approach of developing formal prototypes. Perhaps the association of the arbitrary, throughout history, with a genius of invention, taints the technique too much for Koolhaas to overtly employ. For surely not every building design is required to re-invent the rules, every time.

Page 20

Bibliography Banham, Reyner. Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (London: Thames and Hudson 1976). Basar, Shumon. Learning to love the alien (Casa da Musica, Porto, Portugal), Architecture Today, no. 159 (June 2005) pp. 34-45. Brande, Dirk van de. Maeseneer, Martine de. Rem Koolhaas: Sea trade centre at Zeebrugge: a working Babel, Architectural Design, vol. 62, no. 7-8 (July-Aug 1992) pp. 15-19. Cook, Peter. Archigram (London: Praeger Publishers 1973). Cohn, David. Rem Koolhaas / OMA challenges old notions of what a concert hall should be in the sculptural Casa da Musica in Porto, Portugal, Architectural Record, vol. 193, no. 7 (July 2005) pp. 100-111. Dahinden, Justin. Urban Structure for the Future (London: Pall Mall Press 1971). Eisenman, Peter. Diagram Diaries (London: Thames and Hudson 2001). Fisher, Thomas. Rem Koolhaas and the Office of Metropolitan Architecture explore the arbitrariness of form in these three recent projects, Progressive Architecture, vol. 71, no. 4 (April 1990) pp. 123-125. Giedion, Siegfried. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition (Cambridge: The Harvard University Press 1941). Giovanini, Joseph. On the contrary: The predictably unpredictable Rem Koolhaas defies convention again, Architectural Digest, vol. 59, no. 7 (July 2002) pp. 59-64. Hays, K. Michael. Sanctuaries: The Last Works of John Hedjuk (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art 2002). Hedjuk, John. Vier Entwurfe (Zurich: ETH Press 1983). Koolhaas, Rem. Content (Germany: Taschen 2004). Koolhaas, Rem. Delirious New York (New York: The Monacelli Press 1978). Koolhaas, Rem. S, M, L, XL (New York: The Monacelli Press 1995). Koolhaas, Rem. Transformations, A + U: Architecture and Urbanism, special issue no. 5 (May 2000) pp. 106-115.

Page 21

Kwinter, Sanford. Eisenman Architects: Selected and Current Works (Victoria: The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd 1995). Le Corbusier, Charles-Edouard. The Radiant City; elements of a doctrine of urbanism to be used as the basis of our machine age civilization (New York: Orion Press 1967, first published in 1933). Le Corbusier, Charles-Edouard. Towards a New Architecture (New York: Dover Publications 1986, first English translation published in 1931). Maki, Fumihiko. Investigations in Collective Form (Washington: Washington University School of Architecture 1964). Middleton, R. The Abbe de Cordemoy and the Graeco-Gothic Ideal, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, XXV (1962) pp. 278-320. Moneo, Rafael. Theoretical Anxiety and Design Strategies in the work of Eight Contemporary Architects (Barcelona: Actar 2004). Price, Cedric. Fun Palace, Camden, London, Architectural Review, volume 139 (November 1967) pp. 522-525. Price, Cedric. Fun Palace Project, Architectural Review, vol. 137 (January 1965) pp. 73-75. Price, Cedric. Isozaki, Arata. Keiller, Patrick. Koolhaas, Rem. Re:CP, ed. Obrist, Hans Ulrich (Switzerland: Birkhauser 2003). Reichlin, Bruno. The pros and cons of the horizontal window. The Perret Le Corbusier controversy, Daidalos, no. 13 (September 1984) pp. 64-78. Slessor, Catherine. View from Oporto: Oporto is going to get its Guggenheim, in the shape of OMAs new Casa da Musica, Architectural Review, vol. 216, no. 1289 (July 2004) pp. 34-35. Slessor, Catherine. Delirious Porto: concert hall, Porto, Portugal, Architectural Review, vol. 218, no. 1302 (August 2005) pp. 40-47. Sudjic, Deyan. Wrong about Rem, Log, no. 6 (Fall 2005) pp. 122-128. Vitruvius, Marcus. The Ten Books of Architecture, translated by Mick Morgan, Morris (New York: Dover Publications 1960). Wolfflin, Heinrich. Renaissance and Baroque, translated by Simon, Kathrin (New York: Cornell University Press 1964).

Page 22

You might also like

- Summerson PDFDocument11 pagesSummerson PDFJulianMaldonadoNo ratings yet

- The Italian Approach, Nicola Marzot - RUDI - Resource For Urban Design InformationDocument2 pagesThe Italian Approach, Nicola Marzot - RUDI - Resource For Urban Design InformationHeraldo Ferreira Borges100% (1)

- The Poetry of Architecture: Or, the Architecture of the Nations of Europe Considered in its Association with Natural Scenery and National CharacterFrom EverandThe Poetry of Architecture: Or, the Architecture of the Nations of Europe Considered in its Association with Natural Scenery and National CharacterNo ratings yet

- Villa Giulia Museum's Formal DesignDocument27 pagesVilla Giulia Museum's Formal DesignNicolasPaganoNo ratings yet

- Yale University architecture article on rules and transitionsDocument13 pagesYale University architecture article on rules and transitionsCarlos SeguraNo ratings yet

- Eisenstein, The Glass House and The Spherical BookDocument15 pagesEisenstein, The Glass House and The Spherical BookMarcos VilelaNo ratings yet

- The Architectural ReviewDocument18 pagesThe Architectural ReviewSegher de ReijNo ratings yet

- Cybernetics and Art: Cultural Convergence in The 1960sDocument17 pagesCybernetics and Art: Cultural Convergence in The 1960salepapaNo ratings yet

- ARC181H1 Winter 2020Document10 pagesARC181H1 Winter 2020Barira TahsinNo ratings yet

- How labor has shaped architecture and urbanismDocument27 pagesHow labor has shaped architecture and urbanismSabin-Andrei ŢeneaNo ratings yet

- Paolo Virno, 'Post-Fordist Semblance'Document6 pagesPaolo Virno, 'Post-Fordist Semblance'dallowauNo ratings yet

- Boulle eDocument17 pagesBoulle eLucio100No ratings yet

- The Turn From Culture To Media PDFDocument5 pagesThe Turn From Culture To Media PDF段旭乾No ratings yet

- Somol and Whiting - Doppler PDFDocument7 pagesSomol and Whiting - Doppler PDFKnot NairNo ratings yet

- Superstudio and The Refusal To WorkDocument24 pagesSuperstudio and The Refusal To WorkRNo ratings yet

- Toward An Architecture of Enjo - Henri Lefebvre - 854Document254 pagesToward An Architecture of Enjo - Henri Lefebvre - 854Vu Tien AnNo ratings yet

- Lacan On EngleshDocument37 pagesLacan On Englesharica82No ratings yet

- The First Modems: The Architects of The Eighteenth CenturyDocument32 pagesThe First Modems: The Architects of The Eighteenth CenturymichaelosmanNo ratings yet

- Eisenstein WisemanDocument7 pagesEisenstein WisemanPazuzu8No ratings yet

- E Corbusier: Charles-Édouard JeanneretDocument22 pagesE Corbusier: Charles-Édouard JeanneretNancy TessNo ratings yet

- Edgework: Getting Close, Getting Cut, Getting Out, Bradley L. GarrettDocument1 pageEdgework: Getting Close, Getting Cut, Getting Out, Bradley L. GarrettBradley L. GarrettNo ratings yet

- Ross Wolfe, Architecture and Its Image: Or, Must One Visit Architecture To Write About It? (Spring 2014)Document11 pagesRoss Wolfe, Architecture and Its Image: Or, Must One Visit Architecture To Write About It? (Spring 2014)Ross WolfeNo ratings yet

- Jones, Robert A.Document3 pagesJones, Robert A.donninoNo ratings yet

- 12 Edinburgh LecturesDocument700 pages12 Edinburgh LecturespoesieveriteNo ratings yet

- Le Corbusier - StrasbourgDocument15 pagesLe Corbusier - StrasbourgManuel Tanoira Carballo100% (1)

- Agamben On NudityDocument2 pagesAgamben On NuditymgreifNo ratings yet

- Sifra Lentin - Mercantile Bombay - A Journey of Trade, Finance and Enterprise-Routledge India (2021) (ZDocument146 pagesSifra Lentin - Mercantile Bombay - A Journey of Trade, Finance and Enterprise-Routledge India (2021) (ZnayanashreekalitaNo ratings yet

- Detlef On GlassDocument18 pagesDetlef On GlasstereAC85No ratings yet

- Eric Alliez - Capital Times - Tales From The Conquest of Time (Theory Out of Bounds)Document344 pagesEric Alliez - Capital Times - Tales From The Conquest of Time (Theory Out of Bounds)zvonomirNo ratings yet

- Piranesi and The Infinite Prisons: Spatial VisionDocument16 pagesPiranesi and The Infinite Prisons: Spatial VisionAli AhmedNo ratings yet

- Citta Analoga - Aldo RossiDocument2 pagesCitta Analoga - Aldo RossiSérgio Padrão FernandesNo ratings yet

- Architects Journeys - Gsapp Books (2011) PDFDocument256 pagesArchitects Journeys - Gsapp Books (2011) PDFAndrew Pringle SattuiNo ratings yet

- Basics Design Methods - Accident and The Unconscious As Sources (2017)Document7 pagesBasics Design Methods - Accident and The Unconscious As Sources (2017)Şebnem ÇakaloğullarıNo ratings yet

- HUBERT DAMISCH Today, ArchitectureDocument17 pagesHUBERT DAMISCH Today, ArchitectureTim AdamsNo ratings yet

- Lynn - Intro Folding in ArchitectureDocument7 pagesLynn - Intro Folding in ArchitectureFrancisca P. Quezada MórtolaNo ratings yet

- 9780980819724-Monadology and SociologyDocument105 pages9780980819724-Monadology and Sociologyuser31098No ratings yet

- Vidler TransparencyDocument2 pagesVidler TransparencyDenis JoelsonsNo ratings yet

- Difference and Repetition Gilles DeleuzeDocument4 pagesDifference and Repetition Gilles DeleuzeKika EspejoNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalysis and Post HumanDocument22 pagesPsychoanalysis and Post HumanJonathanNo ratings yet

- Agoraphobia - Simmel and Kracauer - Anthony VidlerDocument16 pagesAgoraphobia - Simmel and Kracauer - Anthony VidlerArthur BuenoNo ratings yet

- Rowe, Colin - Mannerism and Modern Architecture PDFDocument29 pagesRowe, Colin - Mannerism and Modern Architecture PDFMinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- 1999nietzsche ArchitectureDocument3 pages1999nietzsche ArchitectureJaphet TorreblancaNo ratings yet

- Alberto Pérez-Gómez Dwelling On Heidegger Architecture As Mimetic Techno-PoiesisDocument61 pagesAlberto Pérez-Gómez Dwelling On Heidegger Architecture As Mimetic Techno-PoiesisJulianCarpathiaNo ratings yet

- ExtimityDocument12 pagesExtimityDamián DámianNo ratings yet

- The Collected Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: The Complete Works PergamonMediaFrom EverandThe Collected Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: The Complete Works PergamonMediaNo ratings yet

- Robert VenturiDocument14 pagesRobert VenturiUrvish SambreNo ratings yet

- The Well Tempered Drawings of Reflective Architect Marco FrascariDocument10 pagesThe Well Tempered Drawings of Reflective Architect Marco FrascaripipiNo ratings yet

- Form Problems of The GothicDocument210 pagesForm Problems of The GothicVanessa RatoNo ratings yet

- Francois Laruelle On The Work of Gilbert SimondonDocument21 pagesFrancois Laruelle On The Work of Gilbert SimondonCamus AhnNo ratings yet

- Two Projects The Formative Years of Manfredo TafuriDocument18 pagesTwo Projects The Formative Years of Manfredo TafuriIvan MrkvcNo ratings yet

- Hays Mirrors AshesDocument8 pagesHays Mirrors AshesAngelaNo ratings yet

- Backdrop Architecture Projects Explore Urban Intervention in LondonDocument10 pagesBackdrop Architecture Projects Explore Urban Intervention in LondonMuhammad Tahir PervaizNo ratings yet

- Camera Constructs IntroDocument20 pagesCamera Constructs IntroThomas NerneyNo ratings yet

- Interpreting Foucault's Concept of HeterotopiaDocument13 pagesInterpreting Foucault's Concept of HeterotopiaHernan Cuevas ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- 4th GradeDocument24 pages4th Gradeapi-454718946No ratings yet

- Vanna Venturi HouseDocument6 pagesVanna Venturi HouseAbdulla Km0% (1)

- QuotationsDocument4 pagesQuotationschaitanya12299No ratings yet

- MondrianDocument13 pagesMondrianapi-218373666No ratings yet

- Charles Correa's Artist Village cluster patternDocument1 pageCharles Correa's Artist Village cluster patternSiddique SiddNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary: Unscramble The Words BelowDocument2 pagesVocabulary: Unscramble The Words BelowlyzNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 2 HandoutDocument13 pagesTutorial 2 HandoutedsaregNo ratings yet

- Horned MaskDocument8 pagesHorned Maskbri unit tambaksariNo ratings yet

- How Posters Work Skillshare SlidesDocument149 pagesHow Posters Work Skillshare SlidesGefest Mitrandir71% (7)

- Ar. B S Bhooshan: Philosophy and WorksDocument30 pagesAr. B S Bhooshan: Philosophy and WorksLeelaprasad ChigurupalliNo ratings yet

- The History of The PhotographyDocument2 pagesThe History of The PhotographyDiego PulidoNo ratings yet

- Joel Meyerowitz FinalDocument5 pagesJoel Meyerowitz Finalapi-285595577No ratings yet

- Not The Old. Not The New, But The Necessary. Vladimir TatlinDocument6 pagesNot The Old. Not The New, But The Necessary. Vladimir TatlinTawfiq MahasnehNo ratings yet

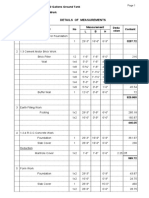

- Sr. Particular No Measurement Content No L B H Dedu Ction: Details of MeasurementsDocument12 pagesSr. Particular No Measurement Content No L B H Dedu Ction: Details of MeasurementsMyo AungNo ratings yet

- Explore the Architectural Elements of Delhi's Historic Lodi GardensDocument12 pagesExplore the Architectural Elements of Delhi's Historic Lodi GardensAbhishek RawatNo ratings yet

- Medieval English ArchitectureDocument3 pagesMedieval English ArchitectureMatías PadillaNo ratings yet

- Deezer BrandBook PDFDocument29 pagesDeezer BrandBook PDFMincho Camacho JimenezNo ratings yet

- Laurie BakerDocument82 pagesLaurie Bakersarath sarathNo ratings yet

- Cristian Graure - Timpul Intr-Un Cadru, Timisoara Fotografica Intre 1860 Si 1900 / Time in A Frame. Photography in Timisoara From 1860 To 1900Document1 pageCristian Graure - Timpul Intr-Un Cadru, Timisoara Fotografica Intre 1860 Si 1900 / Time in A Frame. Photography in Timisoara From 1860 To 1900Graure CristianNo ratings yet

- Goya - Spanish Enlightenment PowerpointDocument9 pagesGoya - Spanish Enlightenment Powerpointapi-218373666No ratings yet

- VarnishesDocument2 pagesVarnishesYonas AddamNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Artisans of The World: Glass Blowers - Murano, ItalyDocument2 pagesTop 10 Artisans of The World: Glass Blowers - Murano, ItalyANDREA TRESVALLESNo ratings yet

- Concrete Quantity SR No. Item Nos. Length (FT) Width (FT) Height (FT) RaftDocument15 pagesConcrete Quantity SR No. Item Nos. Length (FT) Width (FT) Height (FT) RaftMUhammadAHmadNo ratings yet

- Easy Art Project For Kids Pablo Picasso Self PortraitDocument10 pagesEasy Art Project For Kids Pablo Picasso Self PortraitCeleste FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Fine Prints & Photography - Skinner Auction 2609BDocument162 pagesFine Prints & Photography - Skinner Auction 2609BSkinnerAuctions100% (1)

- U3C 報告Document12 pagesU3C 報告朱亦詳No ratings yet

- MDR (MK) - Bukit Asam Convention Hall JakabaringDocument6 pagesMDR (MK) - Bukit Asam Convention Hall JakabaringAdianto Rahman100% (3)

- Kohinoor Case SyudyDocument7 pagesKohinoor Case SyudyNeel Patel75% (4)

- Modern Sculpture Trends in the First Half of the 20th CenturyDocument19 pagesModern Sculpture Trends in the First Half of the 20th CenturyRight LibraNo ratings yet

- M.C. Escher biography highlights graphic artist's impossible structuresDocument3 pagesM.C. Escher biography highlights graphic artist's impossible structuresLauren KelliherNo ratings yet