Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Can Community Micro Farming Create Food Security Case Study 07

Uploaded by

hugo_doolOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Can Community Micro Farming Create Food Security Case Study 07

Uploaded by

hugo_doolCopyright:

Available Formats

F E AT U R E A R T I C L E

Can community-based organic micro-farming create food security?

Although investments in community-based farming and gardening have been modest, a grassroots agricultural movement is steadily growing in South Africa and is fertile ground for CSI. Working through these structures, using a mix of proven development strategies, companies can contribute substantially to building a national food security model fit for replication on a mass scale.

BY ROB SMALL

T SHOULD BE OBVIOUS THAT ALL ECONOMIC, CULTURAL AND POLITICAL life depends on food security as a starting point. While agriculture accounts for a relatively modest portion of gross domestic product (GDP), when it falters so does everything else. Our current economy, as elsewhere in the world, is subject to jobless growth so while GDP continues to grow, unemployment and poverty escalates. Conventional economic indicators which might suggest a healthy economy tend to obscure the health status of its people. The bottom line is that agriculture in all its forms remains a vitally important activity even in modern economies.

Feeding the world or not

It is important, at the outset, to understand the difference between the two main forms of agriculture and their potential impact on food security. On the one hand, high-tech agriculture which includes chemical, hydroponic, GMO production and factory farming is intensive in terms of capital, other inputs as well as outputs. On the other end of the spectrum, organic bio-dynamic farming and gardening which includes permaculture is capital effective, using low external inputs while producing consistent and superior quality outputs. In between are a host of adaptive forms which can loosely be termed ecological agriculture. High-tech agriculture is not readily taken up at community level as it is capital intensive and requires a high level of skill. Based on super-technology, huge crops can be grown quickly. Food Aid organisations can channel market surplus to ensure food security. This works if there is enough free money to buy or subsidise massive amounts of food on a regular basis. In theory, high-tech agriculture can indeed meet all food needs, producing sufficient surplus to supply the poor on an ongoing and sustainable basis. When this day comes and theory and practice meet the rest of this article is academic.

266

A T R I A L O G U E P U B L I C AT I O N

F E AT U R E A R T I C L E S

Organic potential

Organic approaches seek natural sustainability before profit and intensively Demand for potatoes is threatening conserve soil fertility, on-farm biological and seed diversity and indigenous endangered fynbos in the Sandveld region in natural systems and knowledge. On a basic level, organic bio-dynamic farming the Western Cape. The potato industry took and gardening is most readily adaptable to poor or emerging farmers who off after demand for French fries rocketed in cannot easily access costly external inputs and high-tech training. It has the both local and international markets an added advantage of being spontaneously community building and because it average of 2.7 ha of fynbos are lost per annum and 55% of the total Sandveld fynbos has been uses human-scale technology, it is also labour intensive and has the potential destroyed. In 2004, the Sandveld alone beyond meeting subsistence needs to create jobs. It is now a proven fact that produced 26 million of the countrys potatoes. a reasonable living, after costs, is possible off 500 square metres or less, selling Potato farming has a direct effect on water organic vegetables at street prices. consumption in the area, and dam levels are The main criticism levelled at organic agriculture is that it cannot feed the dropping. However, the Greater Cederberg world. But this might be a failure of the economic system in which we operate Biodiversity Corridor (GCBC) has stepped in to rather than the inherent capacity of the approach. There is ample evidence to demarcate land for natural vegetation and is negotiating an ongoing relationship with potato suggest that organic food provides superior nutrition in other words less feeds farmers. more. And while it is true that organic agriculture cannot produce massive surpluses by forcing super-growth, over the long term productivity equals out: organic production is more consistent over time; it is more environmentally sustainable and it creates local economic stability. High-tech agriculture on the other hand has a tendency to spike and plummet during ecological stress-times and macro-economic fluctuations. This is due to a reliance on monocropping systems, which are far more vulnerable to ecological disaster, and the price of expensive external inputs which are heavily debt-reliant. Consider for instance the recent plight of West Coast potato farmers.

Towards localised food security

West Coast potato farmers

Given its potential, the critical question is whether community-based organic agriculture can in fact play a meaningful role in achieving food security. One of its biggest advantages is that organic agricultural methods can easily be transferred to people with few or no previous skills albeit at a basic level. In just four days, anyone can obtain the basic skills which, if applied (with some guidance) over two seasons, will result in a permanent ability to grow productive survival or subsistence gardens at low cost. Although more advanced levels of organic farming require much more training, with the basics in place it is possible to kick-start self-sustaining community farming and gardening in uncontested land such as backyard plots, rural smallholdings, school yards, in servitude and commonage land. Basic-level training can therefore provide a foundation for localised food security among the poor. Indeed, here in South Africa there is now a grassroots organic-friendly farming movement among the poor, involving many thousands who are mobilising to defeat food insecurity. Leading examples are the Vukuzenzela Urban Farmers Association (VUFA) in Cape Town, the Master Farmers Association (MFA) in the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape Ubuntu Farmers Association (WEKUFU). This movement is capable of significantly mitigating local food poverty, but the growth of the movement could be faster.

Obstacles to scaling up

Organic micro-farming methods can easily be transferred to people with few or no previous skills. Basic-level training, achievable in just four days, can provide a foundation for localised food security among the poor.

Perhaps the most significant and intractable obstacle to faster growth of the organic micro-farming sector is the modern consumer mindset. We live in a culture where the desire for instant gratification demands year-round product availability. Consumers wish to benefit from infinite choices and good prices without true accountability for the products consumed. But beyond this generalised cultural inhibitor, there are several specific factors which limit the potential growth of localised food security. These include: G Lack of investment Only a modest investment (compared to the potential for impact) has been made over the last 25 years. This was mainly from corporate, international and private donors. Recently, government is also getting involved in a very small way.

THE CSI HANDBOOK 8th EDITION

267

CHAPTER 6

Easier options Successful agriculture is plain hard work, at least to begin with. Out of necessity the poor are willing to work hard for fresh food and modest incomes but if easier options appear, many move on. Lack of appropriate skills While it is simple to garden at a basic level, and to meet subsistence needs, to be sustainable at higher levels requires more advanced skills. These are not acquired quickly, taking a minimum of three years for beginners. Highlevel training is out of reach for most, as it is expensive and geared for literate people. Lack of subsidies Within our current economic paradigm, agriculture cannot function without subsidies. This also applies to community-based organic agriculture, although to a far lesser degree than high-tech agriculture. In the USA and Europe, agriculture would collapse without multi-level subsidies. In South Africa, where no overt subsidies exist, disintegration would quickly follow if research, cheap extension services, special loan and grant finance or cross-subsidisation were withdrawn. Chronic illness An emerging limiting factor is the debilitating impact of the HIV/Aids pandemic, with increasing numbers of people often precisely in hard-hit communities where food needs are greatest too weak to work.

Intervening at the appropriate level

Despite these limiting factors, the moderate investment in community-based agriculture has born promising fruit. And recently, a step-by-step development continuum for communitybased agriculture has been developed (and will be ready for distribution in 2006). The development continuum takes the limiting factors into account and enables a constructive and empowering flow-through of participants who have other aspirations and need to farm or garden only as a stepping stone. The notion of a development continuum is not new. However, a clear step-by-step pathway for the creation of sustainable community garden and farming projects definitely is. Distinct phases or levels have been identified from field experience, with sustainability measurements at each level. The continuum runs through four phases or levels, from Survival, to Subsistence, to Livelihood and finally to Commercial level. Energy is right now being wasted by donor agencies attempting to move Survival-level farmers up to Commercial level too quickly, while beneficiaries themselves are confused about which level they would like to achieve, or even if they want to be farmers at all! Growing out of the continuum, Abalimi is developing a special training to provide community farmers and gardeners with sustainable assistance, while allowing flow-through of temporary farmers. The training will enable both illiterate and literate people at Survival

THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT CONTINUUM FOR ORGANIC MICRO FARMING PROJECTS

Greatest number of people move through to other things

Least number of people move through

Survival phase Eat Selling and saving begin

Subsistence phase Eat sell save Reinvestment begins

Livelihood phase Eat sell save reinvest Profit earning begins

Commercial phase Sell reinvest profit Job creation begins

Social impacts highest at all stages Greatest number of people benefit and the poverty alleviation movement is most effective

Social impacts decrease Poverty alleviation impact dissipates

268

A T R I A L O G U E P U B L I C AT I O N

F E AT U R E A R T I C L E S

level to progress to the level that suits them, or to eventually achieve Commercial level. The training model also takes account of a new type of community garden that is emerging at Survival, Subsistence and Livelihood levels this is the treatment support garden which supplies fresh organic vegetables to the chronically ill.

Fertile ground for CSI

A grassroots movement is growing, a development pathway has been carved out, essential tools and supplementary approaches have been developed, all of which can change the face of food security sustainably, from the bottom up. The community-based organic agriculture terrain is now comprehensible and fertile ground for social investment initiatives. Working through existing grassroots organisational structures, CSI can contribute enormously to building a sustainable ground-up food security national model. The State whose job it is to take to scale proven models which work can then confidently stimulate replication on a massive scale. In practice, building a more robust micro-farming model might include any number of the following critical interventions: G Funding core costs over a three- to five-year period of organisations with a good track record of developing micro-farming at community level, G Supporting further development and roll-out of the training continuum and accreditation. This might include providing bursaries for trainees at all levels of the continuum, G Supporting capacity-building of community associations through horizontal (farmer-to-farmer) learning, which is a proven high-impact approach, G Enabling savings mobilisation and micro-credit schemes by supplying randfor-rand finance to create revolving loan and credit funds to provide cheap micro-credit for emerging organic growers, G Supporting the development of marketing infrastructure and systems, allowing the poor to gain access to markets, G Funding set-up costs of Local Economic Trading Systems (LETS) already operating successfully in many communities and supplying goods and services through these systems.

Hope for the future

A food secure nation is possible through relatively self-sustaining communitybased initiatives. Quality organic vegetables can and should be abundantly and cheaply available. Rather than grow basic vegetables and foodstuffs for the poor, agribusiness can then refocus and develop the endless possibilities available for elite and export markets. Mind you, they should beware competition from community farmers who by that time will have reached Commercial level!

More information about the development continuum and training for community-based farmers is available from abalimi@iafrica.com Rob Small is an Abalimi Bezekhaya Associate and Ashoka Fellow

There are many development tools that CSI initiatives can use to assist the burgeoning organic community-based agriculture movement. Innovative and proven strategies include: Horizontal Learning exchange Farmer-to-farmer learning has been widely tested and is essential to spread knowledge, skills and commitment and to build community organisations at local level. (Contact: Rob Small abalimi@iafrica.com ) Savings mobilisation Group savings schemes, such as the stokvel approach, whereby people save very small amounts regularly and collectively, is a powerful mobilisation activity among millions. Every community agriculture project should start with a group savings programme. (Contact: abalimi@iafrica.com) Cheap micro loans Once savings mobilisation is established as practice and people are earning a regular if small income, micro loans can be used to encourage higher level entrepreneurial development. Microloans are best applied at upper Livelihood level and at Commercial level. (Contact: Prof Mark Swilling Mark.Swilling@sopmp.sun.ac.za) Local Economic Trading Systems (LETS) LETS allow trading of goods and services, using debt-free local currencies that cannot themselves be traded or invested. LETS will enable enormous growth and sustainability in the food security arena. For instance, cash-poor families will be able to buy food from community gardeners and gardeners will be able to purchase many local services and supplies that they need without cash and without debt. (Contact: ctte@ces.org.za) Community Investment Programmes (CIPs) This approach rapidly enables communities to conceive, form and drive their own sustainable development plans, utilising all of the above interventions. (Contact: Dr. Norman Reynolds marketnr@iafrica.com)

THE CSI HANDBOOK 8th EDITION

269

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Danc AlanDocument3 pagesDanc AlanTeresa PulgaNo ratings yet

- Lentil Research and Development in NepaDocument9 pagesLentil Research and Development in Nepankyadav560% (1)

- RRLDocument1 pageRRLEugene Embalzado Jr.No ratings yet

- Week 4 - PWKDocument4 pagesWeek 4 - PWKhalo akufikaNo ratings yet

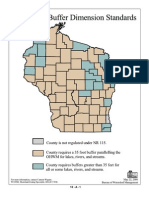

- Shoreland Vegetation - Buffer - Standards by County in WisconsinDocument29 pagesShoreland Vegetation - Buffer - Standards by County in WisconsinLori KoschnickNo ratings yet

- Solution of Linear Programming ProblemDocument12 pagesSolution of Linear Programming ProblemTech_MX100% (2)

- BMP Factsheet DitchblockDocument2 pagesBMP Factsheet Ditchblockapi-278826903No ratings yet

- Wisconsin Native Plant Rain GardensDocument4 pagesWisconsin Native Plant Rain GardensFree Rain Garden Manuals and MoreNo ratings yet

- Texto Agroforestería MARTIN CRAWFORDDocument20 pagesTexto Agroforestería MARTIN CRAWFORDjuliancarrilloNo ratings yet

- The answer is a. PD 330Document33 pagesThe answer is a. PD 330Kenshin FiazylonNo ratings yet

- Xeriscaping Fact Sheet - Hailey, IdahoDocument2 pagesXeriscaping Fact Sheet - Hailey, IdahoAlinso854No ratings yet

- Design and construction of a quinoa grain thresher machineDocument125 pagesDesign and construction of a quinoa grain thresher machineRenzo Alonso CoaquiraNo ratings yet

- Tifton 85 EmailDocument2 pagesTifton 85 Emailtarsands78No ratings yet

- Tugas 1Document4 pagesTugas 1DrackoNo ratings yet

- Potato ProjectDocument10 pagesPotato Projectkillerfox70No ratings yet

- Introduction to Crop Science and AgricultureDocument41 pagesIntroduction to Crop Science and AgricultureGeeflor Panong71% (14)

- The Sloop's Log Spring 2013Document24 pagesThe Sloop's Log Spring 2013Chebeague Island Historical SocietyNo ratings yet

- T8supple2 24 PDFDocument13 pagesT8supple2 24 PDFVenkataraju BadanapuriNo ratings yet

- Download ISSUU PDF Document OnlineDocument154 pagesDownload ISSUU PDF Document OnlineLisandro SosaNo ratings yet

- Weed Control in RiceDocument74 pagesWeed Control in RiceMaribel Bonite PeneyraNo ratings yet

- ASEAN GAP Environmental Management ModuleDocument56 pagesASEAN GAP Environmental Management ModuleASEAN100% (1)

- Harvesting and post-harvest tips for Adlay productionDocument2 pagesHarvesting and post-harvest tips for Adlay productionJayson SebastianNo ratings yet

- Animal HusbandaryDocument16 pagesAnimal HusbandaryManoj BishnoiNo ratings yet

- Blueprint BuffaloDocument12 pagesBlueprint BuffaloAustin BradtNo ratings yet

- Average Annual Daily Traffic - Aadt IN 2019: Network of Ib Category State Roads in Republic of SerbiaDocument10 pagesAverage Annual Daily Traffic - Aadt IN 2019: Network of Ib Category State Roads in Republic of SerbiaРанко ЛасицаNo ratings yet

- Permeable Impermeable SurfacesDocument4 pagesPermeable Impermeable SurfacesAhmed RedaNo ratings yet

- Manangatang Field DayDocument2 pagesManangatang Field DayEric ReeseNo ratings yet

- Weeds in TeaDocument33 pagesWeeds in TeaGuna Pradeep100% (2)

- Cause Effect: Illegal LoggingDocument2 pagesCause Effect: Illegal LoggingJosephine BercesNo ratings yet