Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Techknowlogia Journal 2002 July Sept

Uploaded by

Mazlan ZulkiflyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Techknowlogia Journal 2002 July Sept

Uploaded by

Mazlan ZulkiflyCopyright:

Available Formats

TM

Volume 4, Issue 3 July - September 2002

This issue is co-sponsored by:

Academy for Educational Development and

USAID's Global Bureau, Human Capacity Development Center (G/HDC), under an Indefinite Quantities

Contract (No. HNE-I-00-96-00018-00) to AED/LearnLink.

The contents of this Issue do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of the co-sponsors or their affiliates

Thematic Focus: Technologies for All - Issues of Equity

5 Technologies for All: A Dream or a Nightmare?

Wadi D. Haddad, Editor

The vision of ICTs for All is easy to justify but hard to achieve. An implementation strategy must be realistic

as to recognize the constraints and devise sustainable mechanisms to overcome them.

7 What is The Digital Divide?

Laurence Wolff and Soledad MacKinnon, Inter-American Development Bank

This article briefly describes the digital divide, its scope and reach worldwide, and looks at ways in

which efforts have been made to bridge the divide by increasing access to new technologies.

10 The Many Uses of ICTs for Individuals with Disabilities

Sonia Jurich, and John Thomas, President, CURE Network

Individuals with disabilities have much to gain from the freedom, support and opportunities that can be

offered through the use of assistive technology, adaptive technology, and technology as a tool for knowledge

and support.

12 TechKnowNews

Wearable Computer Gives Voice to Children with Disabilities ♦ "VoGram" to Help Connect India's

Rural, Illiterate Masses ♦ UNESCO Computer/Internet Centre Opened at Education Ministry in Kabul ♦

DigitalOpportunity.org Launched ♦ Report Released on Bridging Global Digital Divide ♦ Egyptians

Spending More Time on the Internet

! 1 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

14 Chilean Schools: The Enlaces Network

Ernesto Laval and J. Enrique Hinostroza, Instituto de Informática Educativa, Universidad de La

Frontera, Chile

In the early 1990's Chile began an educational reform for its primary and secondary school system. The

Enlaces Network is a Chilean initiative for introducing ICT into these schools. This article discusses the

various stages of the program.

19 The Impact of New Technologies on the Lives of Disabled Central Americans: A Model to

Increase Employment and Inclusion

Jessica Lewis and Estela Landeros

This article discusses a program that introduces the use of adaptive ICTs for people with disabilities at

a countrywide level in El Salvador with the goal of increasing their employment opportunities.

24 Uganda School-Based Telecenters: An Approach to Rural Access to ICTs

Meddie Mayanja, ICT Community Development and Business Specialist, World Links

A national School-Based Telecenter (SBT) project was started in Uganda in 2001. It has shown that the SBT

is a potentially strategic initiative that will have impact on ways of helping rural communities functionally cross

the digital divide.

27 The Owerri Digital Village: A Grassroots Approach to Bringing Technology to Nigerian Youth

Njideka Ugwuegbu, Executive Director, Youth for Technology, and Tressa Steffen Gipe

The goal of the Owerri Village is the long-term empowerment of youth through technology knowledge

and skills that will serve as coup de grace against poverty, crime, violence and youth unemployment.

30 Internet Training for Illiterate Populations: Joko Pilot Results in Senegal

Lisa Carney, Joko International, and Janine Firpo, Hewlett-Packard Emerging Market Solutions

Joko is proving that the demystification of new technologies (even to illiterates), is opening doors for

economic development and giving disenfranchised communities new tools to live out their dreams.

34 Mobile Libraries: Where the Schools Are Going to the Students

Sarah Lucas, Education Consultant

This article brings awareness to an old but underused and understudied innovation - the mobile library.

38 India's "Hole in the Wall:" Key to Bridging the Digital Divide?

C.N. (Madhu) Madhusudan, President, Strategic Alliances, NIIT USA Inc.

Could "Minimally Invasive Education" pave the way for a new education paradigm? Read the results of

India's Hole in the Wall project.

! 2 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

41 ICTs for Disadvantaged Children and Youths - Lessons from Brazil and Ecuador

Barbara Fillip, Independent Consultant

Children and youths in poor neighborhoods in developing countries are very likely to be on the wrong side of

the digital divide. Yet the range of beneficial impact of exposure to and training in ICTs on children and

youths is extensive. This article highlights key lessons learned from case studies in Brazil and Ecuador.

45 Botswana: Equity and Access in ICTs - Are We Reaching the Audience We Intended to

Address?

David Motlhale Ratsatsi, Coordinator, World Links for Development, Botswana

Issues of equity are very important factors contributing to quality education and also to empower all in

an equal and equitable manner to enable them to participate fully in the economy. This article looks at

equity at National, Rural/Urban, School and Classroom levels.

49 A Review of Telecenter Effectiveness in Latin America

Joanne Capper

Two recent studies of telecenters in Latin America provide guidance in establishing the strategies

needed to ensure that low-income populations could benefit from Internet connectivity. This article

discusses the findings and recommendations of these studies.

51 Dealing with Gender as an ICT Access Issue

R. D. Colle and R. Roman, Cornell University

This article discusses India's Self Help Groups intermediaries approach as a systematic way to deliver

the benefits of ICTs to bring women in Africa and Asia across the digital divide.

53 ICT for All: Are Women Included?

Marie Fontaine, Academy for Educational Development

This article presents a hypothetical telecenter mini-model that incorporates the essential features

known to be conducive to women's participation in the digital revolution. This telecenter is deliberately

designed to accommodate both men and women equitably. The article also identifies and addresses

some of the common constraints to women's access and usage of ICTs.

58 e-ForALL - A Poverty Reduction Strategy for the Information Age

Francisco J. Proenza, FAO Investment Centre

Countries that seek widespread prosperity and social stability must focus on e-ForAll; i.e. on making the

opportunities that ICTs open up for individual and social improvement accessible to all their citizens.

65 ICTs and Non-Formal Education: Technology for a brighter future?

Anthony Lizardi, The George Washington University

This article discusses recent uses of ICTs in Non-Formal Education and also examines implications for

the future.

! 3 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

68 Packet Radio: Medium Capacity, Low Cost Alternatives for Distance Communication

Kurt D. Moses, Academy for Educational Development

Packet radios, which when integrated become radio modems, provide a chance for a “bottom-up” approach

to communication using “off-the-shelf” equipment and techniques.

71 Understanding Web Page Accessibility: A Focus on Access for the Visually Impaired

Aaron Smith, GW Micro

When contemplating the design of a web page, it is difficult to think of each type of disability and

account for them during the design process. Fortunately, for most users, the adaptation required is

minimal, and access can be gained at almost any location.

73 WorthWhileWebs

Sonia Jurich and Gregg Jackson

This issue focuses on web sites that address two aspects of technologies for people with disabilities: those

that make ICTs accessible to people with disabilities, and those that use ICTs to assist people with

disabilities to handle jobs and daily life activities.

76 Handy 1: A Robotic System to Assist the Severely Disabled

Mike Topping and Jane Smith, Staffordshire University, Stoke on Kent, UK

Handy 1 is a rehabilitation robot designed to enable people with severe disability to gain/regain

independence in important daily living activities. This article describes Handy 1's various assistance tools.

78 Augmenting Communication with Synthesized Facial Expressions - A Controversial New

Technology

Donald B. Egolf, Department of Communication, University of Pittsgurgh

This article describes facial expression synthesis, and its potential uses and controversies.

80 Bringing Mayan Language and Culture across the Digital Divide

Andrew E. Lieberman, Academy for Educational Development

This article describes the "Enlace Quiché" project in Guatemala, which is working in teacher training high

schools to teach students and teachers to create Mayan language instructional materials to show that it is

possible to bring their language and culture with them as Mayans cross the digital divide.

! 4 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

Wadi D. Haddad, Editor

Technologies for All: A Dream or a Nightmare?

There is a growing recognition of the value of information and speed. Likewise, Internet access growth has been ac-

and communication technologies (ICTs) in the lives of peo- companied by some cost reduction. From 1999 to 2004, the

ple as learners, workers, and citizens. Consequently, the ra- number of U.S. households online is estimated to increase by

tionale to bridge the digital divide and provide access to 66% (from 40.5 million to 67.1 million), but spending on

ICTs to all is expanding to cover economic, social, educa- access is estimated to rise by only 9.2% CAGR (compound

tional, political, and equity considerations. annual growth rate). Similarly, broadband Internet access is

expected to increase by 800%, from 2.1 million subscribers

The Challenge in 1999 to 18.9 million in 2004, while broadband spending

will grow by 527%, from US$1.1 billion to US$6.9 billion

The use of ICTs has grown exponentially. In 1950, personal respectively.

computers were little known or used, but within a generation, (www.veronissuhler.com/publications/forecast/highlights.html.)

they became essential work and communication tools.

Similarly, the number of Internet hosts worldwide grew more • Simplification: ICTs strive for simplicity of use, even

than 1,100 times in eight years. (See when the technology becomes gradually more complex. The

www.redhucyt.oas.org/.) first disk operating system- (DOS-) operated PCs required

some training for simple tasks. However, children have no

Despite this phenomenal growth, access varies greatly problems dealing with modern PCs. This concern with the

around the world. Modern ICTs have not corrected the al- user may explain, at least partially, the rapid popularity of the

ready existing divide between technology-rich and technol- medium.

ogy-poor countries created by the Industrial Revolution. As

before, ICT access is related positively to economic devel- • Efficiency: Perhaps more than any other technology,

opment—the higher the income, the greater the ICT access. ICTs strive for efficiency: they are getting faster, simpler,

less costly, more user-friendly and more productive. Auto

But, income is not the only variable that influences access to industries have relied on one source of fuel for the past 100

technology. There are documented inequities across and years, despite warnings ranging from potential depletion of

within countries by race, gender, age, and location. More this sole source to environmental disasters. In less than 50

recently, the limited access to ICTs by persons with disabili- years, telecommunications have experimented with simple

ties and special needs has also been highlighted. telephone lines, fiber optic cables, satellites, and wireless

technologies, and the search continues.

The Hope

There are many reasons for optimism. These trends encourage us not to think in terms of linear

projections. Also countries and communities can leapfrog

• Acceptance: ICTs have been well received worldwide, from pre-technology stages (e.g., the absence of telephone

and it appears that the older technologies have opened the lines) to state-of-the-art strategies (e.g., wireless technolo-

door for the more recent ones. To reach 50 million users, the gies), thus bypassing less efficient and generally more ex-

telephone took 74 years, the radio 38 years, the PC 16 years, pensive alternatives.

the television 13 years, and the WWW only 4 years. In In-

dia, places that did not have a telephone now have Internet

kiosks where families can e-mail their relatives abroad. The Constraints

Likewise, homeless children in Asunción, Paraguay, are The vision of ICTs for All is easy to justify but hard to

learning to read and surf the Web at telecenters where com- achieve. A political commitment is necessary but not suffi-

muters send e-mail messages while waiting for the bus on cient. An implementation strategy must be realistic as to rec-

their way to or from work. ognize the constraints and devise sustainable mechanisms to

overcome them.

• Reduced costs: Increased use of ICTs is associated with

reduced costs and improved technology. Computer hardware

prices have fallen, despite significant increases in memory

! 5 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

• The first and obvious constraint is infrastructure. Until

recently, most ICTs depended on electric power and tele-

TechKnowLogia™

phone lines. Other sources of energy (e.g. solar) and tech- Published by

nologies (wireless, radio, and satellite) offer new opportuni- Knowledge Enterprise, Inc.

ties for access bypassing the traditional technologies.

• Cost is another obvious constraint, despite reduction in EDITOR-IN-CHIEF:

Wadi D. Haddad, President, Knowledge Enterprise, Inc.

unit costs of ICT investments and services. ICT projects re-

quire start-up investments that may challenge the limited

resources of poor countries or locales. However, technolo- INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD:

gies also offer solutions that help to defray costs without Jarl Bengtsson, Head, CERI, OEDC

Claudio Castro, Pres., Advisory Bd., Faculdade Pitágoras

jeopardizing the quality of the projects. Creativity is essen-

Gajaraj Dhanarajan, President & CEO,

tial to overcome potential barriers. Here public-private part- The Commonwealth of Learning

nerships should be explored and encouraged. Dee Dickenson, CEO, New Horizons for Learning

Alexandra Draxler, Director, Task force on Education for

the Twenty-first Century (UNESCO)

• Attention must be paid to laws and regulations that Pedro Paulo Poppovic, Secretary of Distance Education,

could facilitate or hinder ICT plans. ICTs, with their ability Federal Ministry of Education, Brazil

to reach beyond political boundaries, defy many of the na- Nicholas Veliotes, President Emeritus,

tional and international legal frameworks that were created Association of American Publishers

for a world with frontiers. Solutions, albeit necessary, are

difficult to find and slow to implement. The balance between ADVISORY EDITORIAL COMMITTEE:

national and global interests, rights of individuals, and free- Joanne Capper

dom of information is a challenge that must be faced if the Sam Carlson, Executive Director, WorldLinks

Mary Fontaine, LearnLink, AED

potential of ICTs is to be fulfilled. Kathleen Fulton, Nat'l Comm. on Teaching &

America's Future

• Ensuring access to ICTs is just one step. Securing ac- Gregg Jackson, Assoc. Prof., George Washington Univ.

ceptance and use is equally important. Cultural and political Sonia Jurich, Research Assoc., RMC Research Corp.

Frank Method, Consultant, Former Director, UNESCO

factors may promote or create obstacles to the use of ICTs or Washington

limit their use to certain subgroups of society. Likewise, the Kurt Moses, Vice President, AED

structure and organization of local educational systems may Harry Patrinos, Sr. Education Economist, World Bank

favor integration of technology or create a technophobe at- Stephen Ruth, Prof., George Mason University

Laurence Wolff, Sr. Consultant, IDB

mosphere that hinders efforts to change.

• Finally, the provision of ICTs to different segments of MANAGING EDITOR:

society requires local expertise of different kinds: expertise Sandra Semaan

in the potential of ICTs for different needs, strategic exper- GENERAL QUESTIONS OR COMMENTS

tise in planning large-scale innovation projects, technical FEEDBACK ON ARTICLES

expertise related to the hardware, and educational expertise EDITORIAL MATTERS:

in using ICTs for the advancement of knowledge and learn- TechKnowLogia@KnowledgeEnterprise.org

ing. ICT development plans fail when they are transplanted SPONSORSHIP

from outside without regard for the national capacity for de- Sandra@KnowledgeEnterprise.org

sign, customization and implementation.

ADDRESS AND FAX

Knowledge Enterprise, Inc.

The Target P.O. Box 3027

Oakton, VA 22124

ICTs for All is a desirable but elusive target. The needs are U.S.A.

expanding, the demands are escalating, the technologies are Fax: 703-242-2279

evolving, and the resources are diminishing. Will we ever get

there? Probably not. But we can certainly get close through

This Issue is Co-Sponsored By:

sustained pursuit, hard work, exploration, creativity, collabo- Academy for Educational Development (AED),

ration and commitment. and

USAID's Global Bureau, Human Capacity Development

Center (G/HDC), under an Indefinite Quantities Con-

Wadi D. Haddad tract (No. HNE-I-00-96-00018-00) to AED/LearnLink.

! 6 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

What is The Digital Divide? 1

Laurence Wolff and Soledad MacKinnon

Inter-American Development Bank

The Scope

The “digital divide,” inequalities in access to and utilization

of information and communication technologies (ICT), is

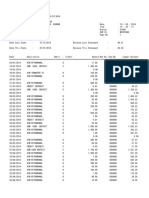

immense. As can be seen in Figure 1, over half of the

households in the USA own computers, compared to less

than 1% in Africa (ITU, 2000).

disabled, single parent (especially female headed) house-

holds, those with little education, and those residing in cen-

tral cities or especially rural areas (NTAI, 1999). The tech-

nology gap is not simply a reflection of the choices made by

individual households, but poor neighborhoods and some

rural communities lack the necessary infrastructure available

in affluent and more populated areas. (Benton Foundation,

1998). The digital divide in other developed countries (e.g.

New Zealand) equally reflects existing disparities in race,

About 77 million computers in the USA have valid Internet income and location (Doczi, 2000).

addresses, while in Bangladesh, Angola, Chad, and Syria

fewer than ten computers are linked to the Internet. Over

time, this division between countries has increased, even as

all countries have steadily increased their number of Internet

users -- as illustrated by Figure 2.

In communication technologies other than computers and

Internet, the divide is significant but not as great. (Figure 3).

Nonetheless is estimated that 80% of the people in the world

have never made a phone call (Digital Dividends, 2001).

The Information Underclass

Even though inequalities in access to ICT are most apparent

across countries, there are also inequalities within countries,

where there is an “information underclass.” In the USA, the

least connected households are those with low incomes,

Black, Hispanic, or Native American, the unemployed, the

! 7 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

While attention is often focused on the disadvantages to an dependent commercial use by local entrepreneurs, which

individual, an equally important problem is the growing un- may generate employment and economic growth. A growing

attractiveness of under-wired locations to business, which ICT service sector may provide better-paid skilled employ-

can lead to “a concentration of poverty and a de- ment, for example by increasing both demand and ability to

concentration of opportunity.” At present, 96% of e- pay for better education, health, and other social services. In

commerce sites are in English and 64% of secure servers are short, affordable access to information infrastructure and the

located in the USA (Bridges, 2001). Finally, while public effective use of the gained knowledge are key factors for

attention often focuses on hardware and interconnectivity, economic sustainability and improved social conditions.

the divide is equally important in terms of human re-

sources—literacy, and people trained and capable of utilizing The “digital divide" is based on insufficient infrastructure, high

ICT and developing appropriate software. The underlying cost of access, inappropriate or weak policy regimes, ineffi-

trend is that privileged groups acquire and use technology ciencies in the provision of telecommunication networks and

more effectively, and because the technology benefits them, services, lack of locally created content, and uneven ability to

they become even more privileged. derive economic and social benefits from information-intensive

activities. To reduce the digital divide requires a “systems”

The Broader “Divides” approach broadly attacking all of these issues. But care must

The digital divide is a sub-set of broader “divides” that char- be taken. Good investments can make ICT an engine for

acterize the world. High cost anti-malarial drugs are provided development. Misguided investments in ICT can divert scarce

to safari-trekkers, at the same time that one African child human and financial resources from more fundamental poverty

dies every 30 seconds because of lack of basic malaria pre- reducing measures.

vention services (Dunavan, 2002). Half the world’s popula-

tion lives on less than $2 a day. About 25% of the world’s Action Points

adult population is illiterate (World Bank, 2001). In 1913 the The Digital Opportunity Task Force (DOT Force), established

gap between the world’s richest quintile and poorest quintile by the Group of 8 (USA, Canada, United Kingdom, Germany,

was 13 to 1. In 1990 it was 60 to 1. In 1997 it was 74 to 1. Italy, France, Japan, and Russia) has set out to define such an

In 1999 the richest 200 people in the world had a combined approach so as to increase access and use of ICT in developing

wealth of $1,135 billion, while the total income of the poor- countries. The DOT Force has proposed the following nine

est half a billion people in all the developing countries barely “action points” for ICT enhancement, which the G8 would

exceeds 10% of that amount (UNDP, 2000). support:

Any program to reduce the digital divide, therefore, has to start • Undertake national e-strategies that would establish ena-

with poverty alleviation, since poverty is by far the greatest bling regulatory and policy frameworks for the growth

impediment to connections with and utilization of ICT. In of ICT.

Bangladesh a computer costs the equivalent of eight years’ • Improve connectivity, increase access and lower costs,

average pay. The cost for Internet connections in Africa ex- through use of multiple competing technologies, public

ceeds the average income of most of the population, while it and community access points, and sharing of best prac-

amounts to 1% of average monthly income in the USA (US tices.

Internet Council, 2000). Poverty reduction, fueled by eco- • Enhance human resource development through actions

nomic and social development, depends on many factors other such as training teachers in ICT, enhancing awareness of

than ICT - political stability, macroeconomic governance, decision makers, and expanding ICT learning opportu-

transparency and accountability of national and local admini- nities to the rural, the poor, and the disenfranchised.

strations, physical infrastructure, and basic literacy. By no • Foster enterprise and entrepreneurship through putting in

means is access to ICT a panacea or short cut for reduction of place pro-competitive policies, encouraging private

poverty. sector innovation, and establishing public/private col-

laboration.

Bridging the Divide • Examine emerging worldwide policy and technical is-

There are, nonetheless, compelling reasons why it is neces- sues raised by the Internet and ICT through a network of

sary to greatly increase public access to new technology. In researchers and policy makers with participation by de-

the first place, even with the Internet “bust” of the last few veloping countries.

years, ICT has become an enormous engine of development. • Make specific efforts to help the countries that are fur-

It is estimated that $2 trillion US dollars were invested in thest behind—the poorest countries, with an emphasis

ICT in 1999. It is reported that the use of ICT contributed on Africa.

close to 50 percent of total growth in US productivity in the • Promote ICT for health education, HIV/AIDs, and other

second half the 1990s (Bridges, 2001). An important addi- communicable diseases

tional benefit of effective use of ICT is the potential for in- • Develop local content through making software applica-

! 8 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

tions widely available, encouraging participation by lo- Conclusion

cal stakeholders, and expanding the languages available In sum, ICT is not the solution to poverty or inequality. In-

on the Internet. vestment in and use of ICT alone is not automatically associ-

• Prioritize assistance for ICT in the initiatives of multi- ated with economic growth. Rather, ICT provides a link in

lateral lending and assistance agencies. the chain of the development process itself. This may reflect

the fact that ICT requires an enabling environment of infra-

These action points constitute the basis for a comprehensive structure and policies before they contribute efficiently to

worldwide effort to reduce the digital divide. economic growth. The task for policy-makers, the business

community, and representatives of civil society is to create

conditions for building the knowledge base in a way that

maximizes the benefits of ICT and reduces the risks.

Sources

Acacia. (1997). Use of Information and Communication Technologies in IDRC Projects: Lessons Learned.

http://www.idrc.ca/acacia/outputs/op-eval3.htm

Analysis Ltd. (2000). The network revolution and the developing world report. A literature review. InfoDev, World Bank,

Washington DC.

Benton Foundation. (1998). Losing Ground Bit by Bit: Low-Income Communities in the Information Age. United States.

http://www.digitaldividenetwork.org

BRIDGES. (2001). Spanning the Digital Divide. http://www.bridges.org

Capper, J. (2001). The promise and challenge of information and communication technologies for development. The World

Bank Institute.

DigitalDividends (2001). Digital Dividends webpage on background to digital divide. http://www.digitaldividend.org/

Doczi, M. (2000). ICTs and Social and Economic Inclusion. March 2000.

http://www.med.govt.nz/pbt/infotech/ictinclusion/ictinclusion.pdf

DOT Force. (2002). Digital Opportunities for All: Meeting the Challenge. http://www.dotforce.org.

Dunavan, Claire Panosia. “Men, Money and Malaria,” Scientific American. June 2002.

ITU (2001). Telecommunication Indicators. http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/at_glance/Internet01.pdf

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTAI). (1999). Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital

Divide. A Report on the Telecommunications and Information Technology Gap in America. NTAI, Department of Commerce.

http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fttn99/

Rodriguez, F. & Wilson, E. (2000). Are poor countries losing the information revolution? InfoDev Working Paper, World

Bank.

UNDP. (2000). Human Development Report. New York.

US Internet Council, "State of the Internet Report 2000," http://www.usic.org

World Bank (2001). World Bank Development Report 2000/1. http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/wdrpoverty/

1

This article draws mainly from two reports, BRIDGES (2001), Spanning the Digital Divide. http://www.bridges.org and DOT

Force. (2002), Digital Opportunities for All: Meeting the Challenge. http://www.dotforce.org.

! 9 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

The Many Uses of ICTs for Individuals with Disabilities

By Sonia Jurich, M.D. & John Thomas, President, CURE Network

Individuals with disabilities have too much to gain from the trauma. The Robot acts as a proxy for muscle strength and

freedom, support and opportunities that can be offered mobility that was lost due to disease or trauma, thus enabling

through the use of ICTs. A discussion of the use of ICTs for an individual to function at a level higher than he or she

individuals with disabilities generally covers three major would otherwise achieve unassisted. ABLEDATA offers a

areas: assistive technology, adaptive technology, and the good introduction to the world of assistive technology with a

technology as a tool for knowledge and support. This article database of close to 30,000 different products

briefly discusses each of the three areas. (http://www.abledata.com). See article "Handy 1: A Ro-

botic System to Assist the Severely Disabled," TechKnowLo-

Assistive Technology gia, this issue.

Any technology that assists individuals to overcome limita-

tions can be called an assistive technology. For example, a Adaptive Technology

crane that lifts and moves hundreds of tons of steel beams is The term adaptive technology indicates the changes that must

assistive technology in the sense that it provides the user be introduced in existing technologies to make them user

with a type of ability that no human being would otherwise friendly for individuals with disabilities. This distinction is

posses. For persons with limited or impaired mobility, not universal and the term assistive technology is frequently

strength, or sensory perception, assistive technology provides used to indicate both devices developed specifically for indi-

resources to bypass or even conquer these limitations. These viduals with disabilities and the adaptations or enhancements

technologies function as a bridge between individuals and of technologies that are intended for general use.

their world; fostering independence and self-confidence.

Examples of simple adaptive technology are keyboards with

A list of assistive technology devices can read like a mail- colorful keys for persons with learning disabilities, or with

order catalog with something for all types of disabilities, large keys for persons with visual impairments. For instance,

ages and individual interests. Products can range from the the HeadMouse is a sophisticated device for persons who do

simple to the sublime, such as battery-operated scissors for not have the use of their hands. The device, placed on the

individuals with carpal tunnel syndrome (pain in the wrist user’s forehead, includes a wireless optical sensor that tracks

region that is exacerbated by repetitive movements of the a target. The user selects a key on the screen keyboard by

thumb), switch-operated toys with a loud buzz for children moving the target over the required key. Voice recognition

with hearing impairments, or time pieces that “speak” the as replacement for keyboarding has become a commercial

hours and minutes of the day for individuals with visual im- alternative even for individuals with no motor disabilities.

pairments. Products can also require extensive financial re- This issue of TechKnowLogia includes an article on facial

sources, such as the Homecare Suite, a prefabricated unit that expression recognition to empower individuals with progres-

can be attached to a home, and caters to persons with physi- sive neuromuscular impairments (Augmenting Communica-

cal disabilities who require daily assistance. tion with Synthesized Facial Expressions: A Controversial

New Technology, by Donald B. Egolf). For individuals who

Assistive technology is not only limited to computerized are blind, documents can be translated into Braille through

technologies. In fact, an assistive device for a person with the use of software and a Braille Embosser (a special type of

impaired mobility can be as rudimentary as a crutch, or as printer). The Adaptive Technology Resource Center, at the

sophisticated as a power wheelchair with voice command. University of Toronto (http://www.utoronto.ca/atrc/), has an

Although many of the basic concepts of assistive technolo- extensive list of devices that can facilitate access and use of

gies have existed for many years, (e.g., wheelchairs or man- computers by individuals with different disabilities.

ual recliner systems), ICTs have expanded this field to new

dimensions. The Development Of Handy 1, A Robotic Sys- An important area of adaptive technology refers to the World

tem To Assist The Severely Disabled, by Mike Topping and Wide Web. The Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), a proj-

Jane Smith, describes a device that uses a simple computer ect of the W3 Consortium,1 has developed a number of re-

technology to increase mobility for persons with severe neu- sources to increase the usability of the web and guidelines for

romuscular limitations, such as persons with advanced mus- web design to make Web content accessible to people with

cular dystrophy (a disease characterized by the progressive disabilities. The guidelines are intended for all Web content

weakening of muscles) or quadriplegia due to a spinal developers (page authors and site designers) and for develop-

! 10 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

ers of authoring tools. The complete guidelines and related technologies have made computers accessible to persons

checkpoints are available at WAI web site with visual impairments, motor and sensorial impairments

(http://www.w3.org/WAI/.) Here are some sample guide- have little impact on the performance of persons working

lines: with computers. Even home-bound individuals can continue

• Provide equivalent alternatives to auditory and vis- working and communicating with colleagues and clients

ual content - Provide content that, when presented to through the Internet. For persons who have social phobia,

the user, conveys essentially the same function or pur- for instance, computers provide a protective wall, facilitating

pose as auditory or visual content. communication with a world that is seen as threatening.

• Don’t rely on color alone - Ensure that text and graph- Computer jobs are therefore a great venue for self-

ics are understandable when viewed without color. sufficiency and personal fulfillment among individuals with

• Use mark up and style sheets and do so properly - disabilities.

Mark up documents with the proper structural elements.

Knowledge and support

Control presentation with style sheets rather than with

As any other group of Internet users, individuals with dis-

presentation elements and attributes.

abilities access the Internet for information, including infor-

• Ensure that pages featuring new technologies trans- mation about their disabilities, available resources, cutting

form gracefully - Ensure that pages are accessible even

edge treatments, and rights. This knowledge empowers the

when newer technologies are not supported or are turned

individuals, bringing back to them the control over their

off.

treatment and future. Many provider organizations, advo-

• Ensure user control of time-sensitive content changes cacy groups and individuals with disabilities maintain web

- Ensure that moving, blinking, scrolling, or auto- sites that offer resources, information and linkages. Three

updating objects or pages may be paused or stopped. examples of web sites for persons with emotional disabilities

• Design for device-independence - Use features that include the Center for Mental Health Services, Knowledge

enable activation of page elements via a variety of input Exchange Network (KEN), funded by the U.S. Department

devices. of Health and Human Services

• Use interim solutions - Use interim accessibility solu- (http://www.mentalhealth.org/), The Internet Mental Health,

tions so that assistive technologies and older browsers a site for information on mental illness and treatment main-

will operate correctly. tained by a Canadian psychiatrist

(http://www.mentalhealth.com/fr01.html) and the Mental

The article Understanding Web Page Accessibility: A Focus

Health Self-Help Network (http://www.mhshn.com), a sup-

On Access For The Visually Impaired, by Aaron Smith, in

port and information site developed and maintained by a

this Issue of TechKnowLogia, explains some strategies in

consumer of mental health services. CURE Network

web design to facilitate accessibility for persons whose vis-

(http://www.cure.org), an organization funded and managed

ual impairment requires the use of a screen reader.

by persons with disabilities, has an extensive list of websites,

newsgroups and listservs encompassing many types of dis-

ICTs for Knowledge and Support abilities.

The third important area in the interaction between ICTs and

individuals with disabilities refers to the use of technologies ICTs are opening new doors, expanding horizons and ena-

as a tool for economic independence and a source of knowl- bling economic independence and emotional balance for

edge and support. many individuals with disabilities. Schools should make an

extra effort to provide students with disabilities with strong

ICTs for economic independence foundations on computer technology skills to improve their

Computer-related technologies have opened the doors of chances of a productive adult life. For the same reasons, it is

economic independence for individuals with different dis- essential that the public and the private sector increase their

abilities for a number of reasons. Most disabilities do not support for research and development, education, and infor-

affect cognitive skills, but motor, neurological or sensorial mation projects that foster new and enhanced technologies

skills. That is, most individuals with disabilities are quite and increase its access to individuals with disabilities. These

intelligent and able to perform well in jobs that demand are necessary steps to move the concept of a more equitable

higher order thinking skills. These are generally jobs that world from utopia into reality.

involve using computers. Since working with computers

requires low mobility or physical strength, and adaptive

1

The W3 Consortium is the international body that sets the standards by which the World Wide Web operates. The Consortium is com-

posed of individuals, corporations and organizations at the cutting edge of web development and use.

! 11 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

TechKnowNews

Wearable Computer Gives Voice "VoGram" to Help Connect India's

to Children with Disabilities Rural, Illiterate Masses

Xybernaut Corporation, known for its wearable computing Scientists at the Indian Institute of Science have developed

technologies, has announced a fully functional wearable an application that would allow the emotion of voice to be

computer platform incorporating hardware, software and conveyed in a telegram. "VoGram" could change the

peripheral technologies designed to help educators empower communication scene by connecting India's largely rural and

students with various learning disabilities. illiterate masses.

The computer, known as Xyberkids, has been tested at The application is a marriage of speech compression, Internet

several schools in the U.S. with promising results. and store and forward messaging ideas. All a person needs to

Xyberkids integrates a variety of educational applications, do is to call up the VoGram call center, record a voice

such as speech and handwriting recognition and peripheral message using a simple card that compresses the voice

devices, into a sturdy backpack that brings the power of a message.

desktop computer to a wearable package to assist teachers

and children in the classroom. The compressed file is sent through the Internet to the post-

office close to the recipients' address. The post-office could

It is used to aid students in a variety of tasks including either print and deliver the message to the recipient or the

written expression, conversion of text and pictures into receiver could call up a local number free of charge, use an

structured speech, supplemental communication through access code given by the postman and hear the VoGram.

audio output devices, augmentation for study habits and

enhancement of organizational skills. Or, better still, if the postman has a Simputer (see

TechKnowNews in TechKnowLogia, May/June 2001 Issue)

The basic XyberKids solution is expected to have a starting he could play the voice message to the recipient at home.

price of $4,995 and is available immediately from Xybernaut

and reseller partners concentrating on the education market. The Indian Institute of Science has sold the application

The solution will be carried in a 15x10x5-inch, heavy-duty license to ILI Technologies, which in turn will market the

polyester and rip-resistant nylon backpack with padded and product in conjunction with the state-owned Indian

adjustable straps. The standard unit features a 500 MHz Telephone Industries.

Intel® Mobile Celeron® processor with 256MB SDRAM, 5

GB internal HDD, as well as Compact Flash, USB and Source: Yahoo India News (May 3, 2002)

Firewire peripheral ports. Students enter and view data using http://in.news.yahoo.com/020503/43/1n7jx.html

the flat panel display, which is an 8.4" viewable (21.3cm) all

light readable display with 800 X 600 color SVGA graphics

capabilities, onscreen keyboard and built-in handwriting UNESCO Computer/Internet

recognition. XyberKids also supports networked and/or Centre Opened at Education

wireless Internet access just as one would experience with a

standard laptop or desktop PC. Ministry in Kabul

Source: BBC News and Xybernaut As reported by UNESCO, May 24, 2002:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/sci/tech/newsid_1893000/18

93074.stm " An Internet equipped computer training centre established

http://www.xybernaut.com/newxybernaut/company/public/pr within the Ministry of Education in Kabul was officially

ess/2002/pub_prss_2002_009.htm opened on Monday (20th May, 2002).

! 12 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

The centre, put in place by UNESCO with funds from the Report Released on Bridging

Government of Japan, is equipped with 19 Compaq Pentium Global Digital Divide

4 computers and a Compaq Proliant server. It also includes

overhead projection equipment for training purposes and a

high-speed Internet connection. The centre is the first of its

kind within any Ministry in Afghanistan. The G8 Digital Opportunities Task Force, also known as

DOTForce, released on June 25, 2002, their reports that

The training facility, which will be utilized by Ministry of outlines how governments, businesses and civil society can

Education staff for developing skills in the use of ICT’s work together to advance human development and reduce

(Information, Communication Technologies) for educational poverty through the use of information and communications

purposes, was opened by Fumio Kishida, Senior Vice- technologies.

Minister of Education with the Ministry of Education,

Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of the Government This report follows up on the 2001 Genoa Plan of Action,

of Japan. He was accompanied by Rasoul Amin, Minister of which called for a concerted plan to narrow the technological

Education of the Afghanistan Interim Administration." gap between developed and developing nations. In less than a

year, the DOT Force has developed a series of initiatives

aimed at forming the key building blocks of the information

Source: UNESCO society for developing countries -- strengthening countries'

http://www.unesco.org/education/news_en/index_archives.sh readiness for e-development, increasing access and

tml connectivity, supporting skills development, as well as

fostering local content and applications.

DigitalOpportunity.org Launched The report can be found online at http://www.dotforce.org.

Source: Industry Canada http://www.ic.gc.ca

May 17, 2002, World Telecommunications Day, was the Egyptians Spending More Time

official launch of the Digital Opportunity Channel on the Internet

(http://www.digitalopportunity.org/). Developed jointly by

OneWorld, the online sustainable development and human

rights network, and the Benton Foundation, the Washington, Egyptians are spending more time on the Internet since the

D.C.-based nonprofit that works to realize the social benefits Internet became free of subscription fees. The Ministry of

of communications technologies, the Channel will focus on Communication and Information Technology (MCIT)

the use of information and communications technologies for arranged a partnership with the state-owned telephone

sustainable development. The site will place a special operator, Telecom Egypt to collect fees for online calls. Use

emphasis on promoting digital opportunities in developing of the Internet for an hour now costs 20 cents, versus the

countries. prior fee of $4 per month for unlimited usage. ISPs were

having difficulty collecting these fees, but are now sharing in

"Developing countries have largely been marginalized in the 70 percent of the revenues collected by the phone company.

global dialogue on the benefits and negative impacts of

digital technologies," said Kanti Kumar, channel editor. The move towards a "free Internet" came in response to

"Digital Opportunity Channel aims to give organizations and Egypt's miniscule Internet usage rate. Out of 69 million

community leaders - especially in the South - a platform for Egyptians, only one million access the Internet. As a

their voice to be heard." developing country, Egypt risks falling further behind as the

global economy becomes increasingly knowledge-based.

Channel features include news, campaign actions, success This is a drive to increase Egypt's online presence.

stories, opinion pieces by leading commentators, in-depth

analysis and research, events listings, a beginner's guide to Source: Wired News

digital divide issues, funding information, email digests and http://www.wired.com/news/business/0,1367,52993,00.html

a dedicated search facility on ICT for development.

Source: DigitalDivideNetwork.org

http://www.digitaldividenetwork.org/content/stories/index.cf

m?key=229

! 13 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

CHILEAN SCHOOLS: The ENLACES Network

Ernesto Laval and J. Enrique Hinostroza

Instituto de Informática Educativa - Universidad de La Frontera, Chile

In the early 90's Chile began an educational reform for its that the solution was not merely the massive provision of

primary and secondary school system. Similar processes took hardware. New technologies were seen as powerful artifacts

place in many countries around the world,1 adjusting educa- that could act as new tools for improving and enhancing

tion to the so-called "Knowledge Society" that was ap- teacher practice within the school. Hardware provision

proaching at the end of the millennium. needed to be part of a larger educational vision that included

clear means for supporting teachers in the use of technology.

Many aspects of the Chilean Educational Reform are similar

to other reforms in the world: new curriculum, better infra- The initial vision was built around the construction of a Na-

structure, text books, more teacher training, more learning tional Educational Network, through which teachers and stu-

time at school, etc. Nevertheless, there are some particular dents could develop professional and pedagogical communi-

aspects of the Chilean context in the 90's that offer a par- ties. This network was called Enlaces, which means 'links' in

ticular flavor: Spanish.

• Chile was initiating a democratic phase after a long pe- Teachers were expected to use technology to communicate

riod of military government. The three presidents elected with other colleagues, sharing problems and solutions, stu-

since 1990 came from the same political coalition, and dents were expected to participate in collaborative projects

gave a high priority and continuity to the educational within their schools and with other schools, and computers

policies of the decade. were seen as a potential pedagogical tool that could support

• The country had a relatively robust economy within the the teaching and learning process within the curriculum.3 In

Latin American Region (GNP per capita of US$4860 in summary, technology was seen as playing several roles in

1996). This situation offered a good framework for education:

funding a large and long-term effort in education. • A pedagogical role: Technology can support learning at

• The 90's were marked with high political and social con- school from a perspective of 'how' students learn (facili-

sensus on the priorities in education, which implied a tating certain learning situations that would be more dif-

national relation between the political system and edu- ficult without technology), but also from a perspective of

cation.2 'what' students learn (learning some concepts or contents

that are easier to understand through digital and interac-

All these factors allowed for the design and implementation tive representations).

of long term and consistent programs articulated around the • A cultural, social and professional role: Computer

Educational Reform. One of these programs was the Chilean networks can enable the formation of new communities

initiative for introducing ICT in primary and secondary of practice.

schools: the Enlaces Network. • An administrative role: Computers can be a powerful

tool for facilitating management and data handling pro-

cedures within the school.

ENLACES NETWORK

An important component of Chilean Educational Reform was We were certain that it was important to have a clear vision

the incorporation of information and communication tech- of the roles of technology in education, but we were also

nologies (ICT) into primary and secondary schools. At the certain that many change processes in education don't suc-

beginning of the 90's there were no clear answers about how ceed if they don't get to an implementation stage: making it

to conduct such a process in the whole country, but we knew happen inside the school. This implementation stage implies

! 14 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

dealing with many variables that are hard to consider - or • Make it simple for the users

even be aware of - from a design desk. Some of the most Teachers were not coming from an ICT culture. Com-

challenging aspects of the implementation stage were: an puters, operating systems, software modems and even

appropriate relation with the school principal, a respectful keyboards could be powerful tools, but they could also

approach to teachers, an appropriate professional develop- be huge barriers for the adoption of technology. From

ment process, a good understanding of the power relation the beginning, Enlaces tried to focus the tasks that

between schools and local authorities, etc. teachers could achieve with computers, and not the

mastery of the computer as and end.

Since we did not have the experience of implementing an

ICT initiative in schools, the decision was to have an initial

It was decided to buy the easiest-to-use hardware and

pilot stage working with a small number of schools (100

software at that time (graphic user interfaces, easy to set

schools) during an extended period of time (5 years) before

up systems, etc.). This could seem to be an expensive

scaling up nationally. This is not an easy decision for a Min-

choice in terms of hardware cost, but turned out to be a

istry of Education, since working on a small scale in educa-

cost-effective solution in terms of usability. An easy to

tion is not popular and might not have high political revenues

use graphic software environment was also developed -

in the short term. Looking backwards we may say that it was

La Plaza - which allowed users to engage in meaningful

a right decision for the long-term implementation of Enlaces.

tasks at the computer within a few hours, even if they

had never seen one before. (see Figure 1)

ENLACES PILOT STAGE:

1992-1995

Enlaces began its pilot stage in 1992 working in educational

and technical aspects of the implementation with just 3

schools in Santiago (Chile's capital city). In 1993, the project

moved to a small city in the south of Chile - Temuco - in one

of the poorest regions of the country. We took the decision of

doing a pilot project in 'difficult' conditions, since if we

could succeed there, then it would be possible to scale up to a

national level. The team that coordinated the pilot project,

and designed the later expansion, was based at the University

of La Frontera, a small University in the city of Temuco,

which became a key partner of the Ministry of Education in

this national ICT program.

After 3 years we were able to build a network of over 100

primary schools that received hardware (computers, printers,

modems), educational software, Internet connection and most

important, a teacher training program that allowed teachers

to use technology. The decision then was to expand at a na- La Plaza (which means 'the central square') was a

tional level, building on the experience gained in the past graphic representation of a common place for Chilean -

three years. The main lessons from this period were: and Latin American - culture. Most Chilean towns have

a central square, which is the place were important

! 15 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

things happen in the town: people meet at the Plaza, the zone. Within each zone, the Zone Center established, in turn,

Post Office is near the Plaza, important buildings are agreements with other universities and institutions - 'Imple-

close to the Plaza, etc. Our computer Plaza was a point mentation Units' - in order to cover all the geographical re-

and click image, where users could go to a Post office gions of the country with a local presence.

(for sending emails), to a News Kiosk (for reading

news), to a Cultural Center (for participation in interest Along with the Enlaces National Support Network, the Min-

groups), and to a Museum (for accessing software and istry maintained a partnership with the Institute for Informa-

information). (see Figure 2) tion Technology in Education at the University of La Fron-

tera, which had conducted the pilot stage. The National Co-

• Focus on Teacher Training ordination of the project was established at the Institute (in

A key dimension of Enlaces work was "training teach- coordination with a team at the Ministry), as well as a Re-

ers". The University that was conducting the pilot proj- search and Development Center, which supported the Minis-

ect established a teacher training team composed ini- try in the design of future steps of Enlaces.

tially of university staff, but later made up mainly of

teachers coming from the first schools in the project. This National Support Network was central to the expansion

due to some key factors:

Teacher training was organized around regular sessions

conducted with teachers in their own schools for a pe- • The implementation of Enlaces in the schools was the

riod of two years. The first year was oriented mainly to- responsibility of institutions that knew the local schools'

wards the use of the computer and software (electronic reality.

mail, word processor, electronic spreadsheet, painting • Institutions appropriated this national initiative as a

programs, educational software), and the second year fo- shared challenge. It was not just the implementation of

cused mainly on the pedagogical application of technol- an official policy from the government, but the imple-

ogy (collaborative learning, curricular projects, etc.). mentation of a program felt as belonging to the whole

country.

• Organizational aspects • A network of specialized teams thinking, reflecting and

It was very important for the development of the project having direct experiences with technology in schools

to have a good organizational structure that offered a was established.

balance between political decisions, design capacities,

• The universities worked with school teachers for training

national articulation, trust, implementation efficacy and

teachers in schools (peer tutoring). This promoted the

funding. This balance was achieved through the partner-

ship established between the Ministry of Education and development of a national network of teacher trainers.

the University.

RURAL ENLACES:

ENLACES NATIONAL EXPANSION: ICT IN SMALL RURAL SCHOOLS

1995-2000 The early years of Enlaces, and the later national expansion,

One of the most critical moments in a project's implementa- was built on a design for large urban schools: arrangement of

tion is when it has to grow from a small - and controlled - computers within a special computer room, training groups

pilot project to a massive, large scale, national program. En- of 20 teachers in weekly sessions at their own school, Inter-

laces faced this challenge in 1995, when it began a national net connectivity through the telephone network, frequent

expansion to the primary education system and at the same technical support, etc.

time it started a national implementation in the secondary

school system. Almost 90% of Chilean students go to these 'urban' primary

or secondary schools. The other 10% of the students attend

A key issue for facing this expansion was the creation of the small rural schools, with a very different context. Some of

'Enlaces National Support Network' that involves a partner- the most salient characteristics of rural schools are as fol-

ship between the Ministry of Education and more than 24 lows:

Universities through the country. Following the scheme • They have a small population of students (an average of

adopted for the pilot stage, 6 universities constituted spe- 27 students per school).

cialized groups of people that would be in charge of provid- • Several classes are taught by the same teacher in one

ing professional development, technical support and devel- classroom (66% have just one teacher).

opment of materials at the regional and local levels. Each of • In spite of the fact that a small proportion of the national

these universities became a 'Zone Center', which was respon- population attend rural schools, the number of these

sible for the implementation of Enlaces in a geographical

schools is relatively high (there are more than 3,300 ru-

! 16 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

ral schools, more than one third of all the schools in the Enlaces National Support Network, provided technical and

country). pedagogical support to each school.6

• Most rural schools are located in places with difficult

access (no public transportation). In summary, the implementation of the Enlaces educational

• About 10% of rural schools do not have regular access network has involved the following:

to electricity. • Providing three years of training to twenty teachers per

• About 80% of rural schools do not have telephone com- school, for an approximate total of 80,000 teachers (70% of

munication. all teachers).

• Reaching 72% of the schools, thus covering 97% of the

The Ministry of Education has a special program for working student population attending state-subsidized institutions.

with rural schools since 1992. This program involves meth- • Supplying 51,000 computers to schools, allocated ac-

odological and organizational approaches that are suitable for cording to the number of students in each school. The

equipment – chosen according to annually updated technical

mixed grade classes, and monthly meetings with teachers

standards – includes multimedia computers, printers, mo-

from nearby schools constituting a community of teachers

dems and a local area network. Considering this equipment

called Microcenter.4 Within this context of Rural Education,

and the ones purchased by each school, the stu-

in 1999 Enlaces designed a special ICT program: Rural En- dents/computer ratio in the country is 42.

laces.5 This program involved a different organization of • Equipping schools with educational software to support

resources within the school (computers arranged as learning their study programs. Annual bidding is held to supply

corners inside the classroom), and a different teacher-training schools with this material. The software includes productiv-

program. ity applications such as word processing, spreadsheets and

graphics programs, along with educational software on topics

Rural Enlaces constituted a network of teams within the such as the human body, space, science, math, geometry,

Zone Centers that were dealing specifically with ICT intro- scientific experimentation, Chilean history, world history,

duction in rural schools. These teams work with rural teacher geography, literature, music, art, drama, physics, chemistry,

trainers - called facilitators - that visit each school once a the environment, etc.

month and work with the teacher and students inside the • Creating a Web site (www.educarchile.cl) that offers a

classroom, modeling different approaches to the incorpora- wide range of useful educational content and services for

tion of technology in pedagogical activities. Besides these teachers and students. This site was conceived as an educa-

'in-classroom' sessions, the facilitator meets with all the tional portal where teachers can find relevant and useful cur-

teachers from nearby schools once a month in their already riculum-oriented content (digital educational resources), fo-

established Microcenter meeting. The first year, teachers also rums on relevant issues and up-to-date education information

participate in special intensive workshops at the closest Uni- (news, events, etc.).

versity, learning basic skills related to the use of computers

• Introducing ICT as a built-in part of the new curriculum

and software. This professional development program is seen

for secondary schools. The use of ICT was defined as a

as a progressive process that takes 3 years, after which they

transversal aim in the curriculum, indicating thereby that it

keep a permanent basic support link with the Enlaces Sup-

should be used in all the core subjects (Language, Math, Sci-

port Network.

ence, etc.) and not as a subject by itself.

In terms of connectivity, it was decided to begin Rural En-

A crucial step in the development of Enlaces was the Agree-

laces with a focus of the pedagogical use of technology in-

ment that the Ministry of Education negotiated with one of

side the classroom even if the schools did not have Internet

the largest telephone companies in the country - Telefonica

access. In parallel, there is a task team designing a national

CTC Chile. The company agreed to provide telephone lines,

solution for providing sustainable Internet access to all the

email accounts and dialup Internet at no cost for a period of

rural schools - and communities - in the following years.

10 years to all the schools in the regions where the company

had a telephone network (the majority of the Chilean

ENLACES’ ACHIEVEMENTS BY Schools).

THE YEAR 2002

By the year 2002 more than 7,300 primary and secondary EVALUATION RESULTS

schools have been incorporated to Enlaces. Each of these In general terms, the results of the evaluations of the effects

schools received computers, local networks, educational and of Enlaces done at an early stage of the project 7 (between

productivity software and free and unlimited Internet access. 1993 and 1997), coincide to show positive outcomes in

Additionally, the Ministry of Education, in a partnership with learning (students increased their reading capacity and their

comprehension levels) and psychological effects (students

! 17 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

improved their creativity, self-esteem, and concentration

capacities). These results are congruous with results of

ENLACES: NEXT STEPS

qualitative evaluation, indicating that technology produces a We recognize that the task is far from being completed. We

high level of motivation among students, generates a more had provided just a basic seed that allowed schools and

horizontal social organization within the classroom, and en- teachers to recognize the potential benefits of ICT. Technol-

ables students to feel proud of their participation in projects, ogy has already been incorporated into the school culture, but

with a corresponding increase in self-esteem. it has not really incorporated into teachers' regular teaching

practice. If ICT is to make a contribution to teaching and

From the point of view of teachers, the comparative evalua- learning practices, we still have a long road to follow. The

tion made of programs introducing computers into the edu- next steps of Enlaces are directed towards the effective Cur-

cational systems in Costa Rica and Chile8 showed that En- ricular Integration of ICT. Several task teams are working on

laces is a source of pride that opens doors for professional priority areas (particularly basic skills of Literacy and Nu-

development, especially among teachers. School officials meracy in primary education), not only trying to understand

also valued the increase in equity that the project provides by the potential benefits of technology, but more importantly the

outfitting schools with equipment that they otherwise would key knots in teaching and learning within the disciplines.

not have been able to acquire. However, a main concern That is, we are trying to answer the question: where and how

among teachers is the heavy unpaid workload resulting from can technology help the teaching and learning process

their participation in the Program. within each discipline? The main idea is that we are not just

providing resources and training, but that we have to design

From a general perspective, evaluations made by the World 'modes of action' for teaching with the use of technology, as

Bank,9 UNESCO10 and the U.S. Agency for International mediators in the teaching process in the domains were tech-

Development11 coincide to highlight the Enlaces project as nology can have an impact.

one of the successful programs in the Chilean Educational

Reform. An important point in this positive evaluation is that We still have more questions than answers for the next steps

the project has expanded its coverage to the national level in Enlaces, but we do know that this is not a neatly designed

without sacrificing quality or equity. Among the factors in 'single shot' intervention, but a long term process in which

this success, they mention the program’s focus on teachers, we will have to continue working with schools and the na-

the construction of a social network of educators and pupils tional - and international - community to build new under-

facilitated by user-friendly technology and decentralized standings and support networks for incorporating ICT for the

support, and respect for participating schools’ autonomy and enhancement of our students’ learning.

their decisions in the use of the program’s technologies.

ENDNOTES

1

Fullan, M., The new meaning of educational change. 3rd ed. 2001, New York: Teachers College Press. xiv, 297.

2

Cox, C., La Reforma de la Educación Chilena: Contexto, Diseño, Implementación. 1997, PREAL: Santiago, Chile.

3

Hepp, P., Enlaces: Todo un mundo para los niños y jóvenes de Chile, in La reforma educacional Chilena, J.E. Garcí-

Huidobro, Editor. 1999, Editorial Popular: Madrid. p. 289-303.

4

San Miguel, J., Programa de Educación Básica Rural, in La Reforma Educacional Chilena, J.E. García-Huidobro, Editor.

1999, Editorial Popular: Madrid.

5

IIE, Enlaces Rural "La informática como un recurso de aprendizaje para todas las escuelas rurales de Chile". 2000,

Universidad de La Frontera: Temuco.

6

Laval, E., Informática Educativa en Chile: Experiencia y proyecciones de la Red Enlaces. Persona y Sociedad, 2001. XV(2).

7

The methodology considered a quasi-experimental design with chronological series using successive pre and post tests. The

sample consisted of 52 primary schools (10,500 students) and 49 secondary schools (5,600 students).

8

Potashnik, M., Rawlings, L., Means, B., Alvarez, M. I., Roman, F., Dobles, M. C., Umaña, J., Zúñiga, M., & García, J.,

Computers in Schools: A qualitative study of Chile and Costa Rica, in Education and Technology Series Special Issue. 1998,

World Bank Human Development Network: Washington D.C.

9

Ibid.

10

Núñez, I., El Proyecto Enlaces (Chile), un estudio de caso. 1996, UNESCO.

11

Rusten, E., Contreras-Budge, E., Tolentino, D., in Learnlink Case Study Summary. "Enlaces: Building a National Learning

Network". 1999, Global Communication & Learning Systems. US Agency for International Development. Available in:

http://www.aed.org/learnlink.

! 18 ! TechKnowLogia, July - September 2002 © Knowledge Enterprise, Inc. www.TechKnowLogia.org

The Impact of New Technologies on the Lives of Disabled Central Americans:

A MODEL TO INCREASE EMPLOYMENT AND INCLUSION

By Jessica Lewis and Estela Landeros

Trust then designed a more in-depth program with additional

VICTORIA’S VICTORY job-readiness training and training for businesses specifically

for El Salvador. This program introduces the use of adaptive

Victoria Martínez Orellana, a twenty-three year old Salva- information and communication technologies (ICTs) for

doran, was born with a congenital deformity in the lower half people with disabilities at a countrywide level in El Salvador

of her body. For many years, she had to use her arms as with the goal of increasing their employment opportunities.

crutches to move herself. Now, however, through the Trust Its engine is a cadre of volunteers and local staff who train

for the Americas’ technology and job-readiness training pro- trainers in computer technologies. These groups then repli-

gram and the help of the Universidad Don Bosco and Gesell- cate the training with their constituents. Local businesses are

shaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (UDB-GTZ) project, partners and ensure that the training given responds to the

she has a wheelchair and a new job at a computer center at a demands of the market and that the people who participate

local school. are able to find a job. This is the only program in Latin

America offering ICT and assistive technology training as

Victoria’s story demonstrates the powerful impact of the new well as job readiness skills training to the disabled. All

technologies on the life of a person with disabilities. Victoria manuals and training modules were designed and tested with

joined the Trust’s Disabilities and Technology program in El people with disabilities.

Salvador in the summer of 2000. Through this program, she

received training in computer skills and job-readiness that Since the start of the Disability and Technology program in

prepared her for her job. To get the job, she had to pass a El Salvador in June 2001, The Trust has trained over 304

series of tests on Windows, Excel, and Power Point. Based disabled Salvadorans and placed 35 people in new jobs. In

on her computer expertise and job-preparation skills she addition, 45 program participants were promoted in jobs that

gained through The Trust program, she succeeded. “Various they had before starting the program while 185 trainees are

people had discriminated against me when I looked for a currently participating in job placement programs. The Trust

job,” explained Victoria. Her new boss, however, told her, has also trained 75 local firms on the issues related to em-

“We don’t discriminate against anyone. I know you are ca- ployment for a person with a disability and trained over 27

pable of doing the job.” non-governmental organizations in the use of these technolo-

gies. The U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of International

For decades, people with disabilities, like Victoria, have Affairs funds the Trust's El Salvador program.

faced discrimination. In Latin America, people with disabili-

ties have had less access to educational and training pro-

grams suited to fulfill their special needs. In countries with

high unemployment rates, a person with a disability has

PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN EL SALVADOR

fewer opportunities to compete for a job. This situation,

along with employers' requirements for training in the use of Victoria’s accomplishment is even more significant in the

information and communication technologies, makes job context of the larger unemployment situation in El Salvador

searching more difficult for them. For these reasons, the and unemployment for people with disabilities. In Latin

Technology and Disabilities program concentrates on train- America, in general, people with disabilities face many

ing people with disabilities in the use of state-of-the-art as- challenges to fully participate in society as equal economic,

sistive technology in order to facilitate their integration in the social, and political players. In countries with high poverty

labor market. rates, people with disabilities are often the last to receive

services and support. Because many of these countries have

The Trust’s Disability and Technology program started as a significant unemployment and underemployment rates for

regional program in four Central American countries that the general population, people with disabilities face an even

sent high-tech volunteers to train disability organizations and greater challenge finding meaningful employment. In El

their constituents in the use of the new technologies. The Salvador approximately 17% of its 6 million people have a