Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kanchan

Uploaded by

Hanisha GuptaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kanchan

Uploaded by

Hanisha GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction

Performance Appraisal

The history of performance appraisal is quite brief. Its roots in the early 20th

century can be traced to Taylor's pioneering Time and Motion studies. But this

is not very helpful, for the same may be said about almost everything in the fie

ld of modern human resources management.

As a distinct and formal management procedure used in the evaluation of work per

formance, appraisal really dates from the time of the Second World War - not mor

e than 60 years ago.

Yet in a broader sense, the practice of appraisal is a very ancient art. In the

scale of things historical, it might well lay claim to being the world's second

oldest profession!

There is, says Dulewicz (1989), "... a basic human tendency to make judgements a

bout those one is working with, as well as about oneself." Appraisal, it seems,

is both inevitable and universal. In the absence of a carefully structured syste

m of appraisal, people will tend to judge the work performance of others, includ

ing subordinates, naturally, informally and arbitrarily.

The human inclination to judge can create serious motivational, ethical and lega

l problems in the workplace. Without a structured appraisal system, there is lit

tle chance of ensuring that the judgements made will be lawful, fair, defensible

and accurate.

Performance appraisal systems began as simple methods of income justification. T

hat is, appraisal was used to decide whether or not the salary or wage of an ind

ividual employee was justified.

The process was firmly linked to material outcomes. If an employee's performance

was found to be less than ideal, a cut in pay would follow. On the other hand,

if their performance was better than the supervisor expected, a pay rise was in

order.

Little consideration, if any, was given to the developmental possibilities of ap

praisal. If was felt that a cut in pay, or a rise, should provide the only requi

red impetus for an employee to either improve or continue to perform well.

Sometimes this basic system succeeded in getting the results that were intended;

but more often than not, it failed.

For example, early motivational researchers were aware that different people wit

h roughly equal work abilities could be paid the same amount of money and yet ha

ve quite different levels of motivation and performance.

These observations were confirmed in empirical studies. Pay rates were important

, yes; but they were not the only element that had an impact on employee perform

ance. It was found that other issues, such as morale and self-esteem, could also

have a major influence.

As a result, the traditional emphasis on reward outcomes was progressively rejec

ted. In the 1950s in the United States, the potential usefulness of appraisal as

tool for motivation and development was gradually recognized. The general model

of performance appraisal, as it is known today, began from that time.

Modern Appraisal

Performance appraisal may be defined as a structured formal interaction between

a subordinate and supervisor, that usually takes the form of a periodic intervie

w (annual or semi-annual), in which the work performance of the subordinate is e

xamined and discussed, with a view to identifying weaknesses and strengths as we

ll as opportunities for improvement and skills development.

In many organizations - but not all - appraisal results are used, either directl

y or indirectly, to help determine reward outcomes. That is, the appraisal resul

ts are used to identify the better performing employees who should get the major

ity of available merit pay increases, bonuses, and promotions.

By the same token, appraisal results are used to identify the poorer performers

who may require some form of counseling, or in extreme cases, demotion, dismissa

l or decreases in pay. (Organizations need to be aware of laws in their country

that might restrict their capacity to dismiss employees or decrease pay.)

Whether this is an appropriate use of performance appraisal - the assignment and

justification of rewards and penalties - is a very uncertain and contentious ma

tter.

Controversy, Controversy

Few issues in management stir up more controversy than performance appraisal.

There are many reputable sources - researchers, management commentators, psychom

etricians - who have expressed doubts about the validity and reliability of the

performance appraisal process. Some have even suggested that the process is so i

nherently flawed that it may be impossible to perfect it (see Derven, 1990, for

example).

At the other extreme, there are many strong advocates of performance appraisal.

Some view it as potentially "... the most crucial aspect of organizational life"

(Lawrie, 1990).

Between these two extremes lie various schools of belief. While all endorse the

use of performance appraisal, there are many different opinions on how and when

to apply it.

There are those, for instance, who believe that performance appraisal has many i

mportant employee development uses, but scorn any attempt to link the process to

reward outcomes - such as pay rises and promotions.

This group believes that the linkage to reward outcomes reduces or eliminates th

e developmental value of appraisals. Rather than an opportunity for constructive

review and encouragement, the reward-linked process is perceived as judgmental,

punitive and harrowing.

For example, how many people would gladly admit their work problems if, at the s

ame time, they knew that their next pay rise or a much-wanted promotion was ridi

ng on an appraisal result? Very likely, in that situation, many people would den

y or downplay their weaknesses.

Nor is the desire to distort or deny the truth confined to the person being appr

aised. Many appraisers feel uncomfortable with the combined role of judge and ex

ecutioner.

Such reluctance is not difficult to understand. Appraisers often know their appr

aisees well, and are typically in a direct subordinate-supervisor relationship.

They work together on a daily basis and may, at times, mix socially. Suggesting

that a subordinate needs to brush up on certain work skills is one thing; giving

an appraisal result that has the direct effect of negating a promotion is anoth

er.

The result can be resentment and serious morale damage, leading to workplace dis

ruption, soured relationships and productivity declines.

On the other hand, there is a strong rival argument which claims that performanc

e appraisal must unequivocally be linked to reward outcomes.

The advocates of this approach say that organizations must have a process by whi

ch rewards - which are not an unlimited resource - may be openly and fairly dist

ributed to those most deserving on the basis of merit, effort and results.

There is a critical need for remunerative justice in organizations. Performance

appraisal - whatever its practical flaws - is the only process available to help

achieve fair, decent and consistent reward outcomes.

It has also been claimed that appraisees themselves are inclined to believe that

appraisal results should be linked directly to reward outcomes - and are suspic

ious and disappointed when told this is not the case. Rather than feeling reliev

ed, appraisees may suspect that they are not being told the whole truth, or that

the appraisal process is a sham and waste of time.

The Link to Rewards

Research (Bannister & Balkin, 1990) has reported that appraisees seem to have gr

eater acceptance of the appraisal process, and feel more satisfied with it, when

the process is directly linked to rewards. Such findings are a serious challeng

e to those who feel that appraisal results and reward outcomes must be strictly

isolated from each other.

There is also a group who argues that the evaluation of employees for reward pur

poses, and frank communication with them about their performance, are part of th

e basic responsibilities of management. The practice of not discussing reward is

sues while appraising performance is, say critics, based on inconsistent and mud

dled ideas of motivation.

In many organizations, this inconsistency is aggravated by the practice of havin

g separate wage and salary reviews, in which merit rises and bonuses are decided

arbitrarily, and often secretly, by supervisors and managers.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- ADocument16 pagesAHanisha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Global WarmingDocument8 pagesGlobal WarmingHanisha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Global Warming: Submitted in Partial Fulfillment For The Award of Degree ofDocument47 pagesGlobal Warming: Submitted in Partial Fulfillment For The Award of Degree ofHanisha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Stress Management in BPODocument47 pagesStress Management in BPOsheemankhan100% (4)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Explanation of Johari WindowDocument3 pagesExplanation of Johari WindowNorman AzaresNo ratings yet

- Understanding Transactional Analysis (TADocument5 pagesUnderstanding Transactional Analysis (TAadivityaNo ratings yet

- Mod 06666Document1 pageMod 06666Aurea Jasmine DacuycuyNo ratings yet

- NCI Test Without Answer SheetDocument6 pagesNCI Test Without Answer SheetMistor Dupois WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Transformational Leadership Versus Authentic LeadershipDocument7 pagesTransformational Leadership Versus Authentic Leadershipapi-556537858No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Solved MCQs (Set-5)Document6 pagesEntrepreneurship Solved MCQs (Set-5)Ecy YghiNo ratings yet

- Holistic Leadership ModelDocument5 pagesHolistic Leadership ModelCMay BidonNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse Paper FinalDocument12 pagesChild Abuse Paper FinallachelleNo ratings yet

- Personal Characteristics and Job Satisfaction (Demography Factors)Document14 pagesPersonal Characteristics and Job Satisfaction (Demography Factors)Li NaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Anger ManagementDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Anger Managementaflsmperk100% (1)

- Laws and TheoriesDocument20 pagesLaws and TheoriesMK BarrientosNo ratings yet

- Moduel 1 Assignment SANA PARVEEN RollNo D17891Document9 pagesModuel 1 Assignment SANA PARVEEN RollNo D17891furqan ulhaqNo ratings yet

- Organizational Diagnosis: Current and Desired Performance and How It Can Achieve Its GoalsDocument3 pagesOrganizational Diagnosis: Current and Desired Performance and How It Can Achieve Its GoalstalakayutubNo ratings yet

- Autism Summary of Evidence For Effective Interventions November 2019Document24 pagesAutism Summary of Evidence For Effective Interventions November 2019JCI ANTIPOLONo ratings yet

- Evidence Claim Assessment WorksheetDocument3 pagesEvidence Claim Assessment WorksheetYao Chong ChowNo ratings yet

- The DangerousDocument10 pagesThe DangerousYuwan RamjadaNo ratings yet

- 5036 Asm2 GBS210986Document26 pages5036 Asm2 GBS210986Nguyen Thi Hoai Thuong (FGW HCM)No ratings yet

- Sociology 1Document2 pagesSociology 1Drip BossNo ratings yet

- World Class ABA ProviderDocument24 pagesWorld Class ABA ProviderMarioara SecobeanuNo ratings yet

- Williams Memory Screening TestDocument17 pagesWilliams Memory Screening TestStella PapadopoulouNo ratings yet

- Classification of Psychiatric DisordersDocument64 pagesClassification of Psychiatric Disordersdrkadiyala2100% (1)

- ReflectingDocument15 pagesReflectingZrazhevska NinaNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Sciences GuideDocument14 pagesBehavioral Sciences GuideAiDLo100% (1)

- Compassionate Love As Cornerstone of Servant LeadershipDocument14 pagesCompassionate Love As Cornerstone of Servant LeadershipAnthony PerdueNo ratings yet

- Bronfrenbrener TheoryDocument11 pagesBronfrenbrener TheoryNnil GnuamNo ratings yet

- Coherencia Cardiaca HeartMathDocument6 pagesCoherencia Cardiaca HeartMathLEIDY MENDIETANo ratings yet

- The Power of Pets: Health Benefits of Human-Animal InteractionsDocument4 pagesThe Power of Pets: Health Benefits of Human-Animal InteractionsDamarisse MirandaNo ratings yet

- Communication Skills - Module 1Document7 pagesCommunication Skills - Module 1Hanniem KimNo ratings yet

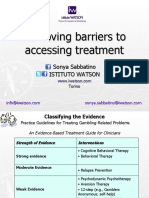

- Eacbt Sabbatino Mi 2010Document18 pagesEacbt Sabbatino Mi 2010Sonya SabbatinoNo ratings yet

- Research Project Survey InstructionsDocument7 pagesResearch Project Survey InstructionsAimee Tarte0% (1)