Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Searcy v. Harris (11th Cir 1989)

Uploaded by

Colin HectorOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Searcy v. Harris (11th Cir 1989)

Uploaded by

Colin HectorCopyright:

Available Formats

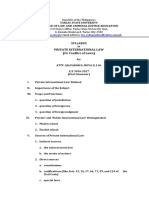

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 1

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

West Headnotes

United States Court of Appeals, [1] Constitutional Law 92 1735

Eleventh Circuit.

Emory SEARCEY, Tom Coffin, Zachary Coffin, 92 Constitutional Law

Constancia Romilly, Chaka Forman, Anne Nich- 92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and

olson, Eric Carter, Don Stone, John Storey, Flora Press

Stone and the Atlanta Peace Alliance, Plaintiffs- 92XVIII(G) Property and Events

Appellees, 92XVIII(G)2 Government Property and

v. Events

J. Jerome HARRIS, individually and in his official 92k1732 Public Forum in General

capacity as Superintendent of the Atlanta Public 92k1735 k. Justification for Exclu-

Schools, Atlanta Board of Education, Defendants- sion or Limitation. Most Cited Cases

Appellants, (Formerly 92k90.1(4))

United States of America, Intervening-Defendant,

Constitutional Law 92 1747

Appellee.

No. 88-8327. 92 Constitutional Law

92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and

Nov. 21, 1989.

Press

Peace organization brought suit challenging school 92XVIII(G) Property and Events

board's denial of their request to present certain in- 92XVIII(G)2 Government Property and

formation to public high school students during Events

“career day.” The United States District Court for 92k1744 Designated Public Forum in

the Northern District of Georgia, 642 F.Supp. 313, General

preliminarily enjoined school board from denying 92k1747 k. Justification for Exclu-

organization opportunity to participate in program, sion or Limitation. Most Cited Cases

but deferred question as to whether organization (Formerly 92k90.1(4))

could discuss merits of military service at program. In traditional public forum and in created public

On appeal, the Court of Appeals, 815 F.2d 1389, af- forum, government may enforce content-based re-

firmed in part and vacated in part. On remand, the strictions on speech only if necessary to serve com-

District Court, No. 1:84-cy-751-MHS, Marvin H. pelling state interest and narrowly tailored to serve

Shoob, J., 681 F.Supp. 821, determined that restric- that interest; government may also enforce content

tions placed upon organization's participation viol- neutral regulations which are narrowly tailored to

ated First Amendment, and school board appealed. serve significant interest but still leave open ample

The Court of Appeals, Clark, Circuit Judge, held alternative means of communications. U.S.C.A.

that: (1) present affiliation regulation was unduly Const.Amend. 1.

restrictive, and (2) to extent that speaker discour-

[2] Constitutional Law 92 1751

ages students from entering specific career by

providing students with valid and informative dis- 92 Constitutional Law

advantages of that career, such was appropriate and 92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and

allowable. Press

92XVIII(G) Property and Events

Affirmed as modified.

92XVIII(G)2 Government Property and

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 2

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

Events 345k66 School Buildings

92k1748 Non-Public Forum in General 345k72 k. Control and Use. Most Cited

92k1751 k. Justification for Exclu- Cases

sion or Limitation. Most Cited Cases School board's requirement that presenter at public

(Formerly 92k90.1(4)) high school “career day” have direct knowledge of

In nonpublic forum, government may impose con- career was reasonably related to purposes of career

tent-based restrictions which are reasonable and are day program; however, requirement that presenter

not effort to suppress expression merely because also have present affiliation with career was unreas-

public officials oppose speaker's view. U.S.C.A. onable; it was not demonstrated that individuals

Const.Amend. 1. who were no longer affiliated with career would

have less information or would present less effect-

[3] Constitutional Law 92 1965 ive role model nor was it obvious that such indi-

viduals would be more likely to turn career day into

92 Constitutional Law

forum for political views. U.S.C.A. Const.Amend.

92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and

1.

Press

92XVIII(Q) Education [5] Constitutional Law 92 1970

92XVIII(Q)1 In General

92k1965 k. In General. Most Cited 92 Constitutional Law

Cases 92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and

(Formerly 92k90.1(1.4)) Press

While court must defer to reasonable educational 92XVIII(Q) Education

decisions made by educators, when particular de- 92XVIII(Q)1 In General

cision implicating First Amendment has no valid 92k1968 Access to Facilities and Other

educational purpose, First Amendment is so dir- Public Places; Public Forum Issues

ectly and sharply implicated as to require judicial 92k1970 k. Outside Persons or Or-

intervention. U.S.C.A. Const.Amend. 1. ganizations. Most Cited Cases

(Formerly 92k90.1(1.4))

[4] Constitutional Law 92 1970

Schools 345 72

92 Constitutional Law

92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and 345 Schools

Press 345II Public Schools

92XVIII(Q) Education 345II(D) District Property

92XVIII(Q)1 In General 345k66 School Buildings

92k1968 Access to Facilities and Other 345k72 k. Control and Use. Most Cited

Public Places; Public Forum Issues Cases

92k1970 k. Outside Persons or Or- School board's regulations banning criticism at pub-

ganizations. Most Cited Cases lic high school “career day” were reasonable only

(Formerly 92k90.1(1.4)) to extent they prohibited group from denigrating

opportunities offered by other group; however, reg-

Schools 345 72 ulations were unreasonable to extent that they pro-

hibited group from presenting negative factual in-

345 Schools

formation about disadvantages of specific job op-

345II Public Schools

portunities. U.S.C.A. Const.Amend. 1.

345II(D) District Property

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 3

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

[6] Constitutional Law 92 1970 Jeffrey O. Bramlett, Bondurant, Mixon & Elmorf,

Cathleen M. Mahoney, Atlanta, Ga., for amicus,

92 Constitutional Law Presbyterian Church of USA.

92XVIII Freedom of Speech, Expression, and

Press

92XVIII(Q) Education Appeal from the United States District Court for the

92XVIII(Q)1 In General Northern District of Georgia.

92k1968 Access to Facilities and Other

Before KRAVITCH and CLARK, Circuit Judges

Public Places; Public Forum Issues

and HENDERSON, Senior Circuit Judge.

92k1970 k. Outside Persons or Or-

ganizations. Most Cited Cases

(Formerly 92k90.1(1.4)) CLARK, Circuit Judge:

Schools 345 72 The Atlanta Peace Alliance (APA) challenged the

policy of the Atlanta School Board regarding access

345 Schools of military and nonmilitary groups to the Atlanta

345II Public Schools FN1

schools. The APA brought suit contending that

345II(D) District Property the School Board's refusal to grant the APA access

345k66 School Buildings to programs known as Career Day and Youth Mo-

345k72 k. Control and Use. Most Cited tivation Day and to place information on bulletin

Cases boards and in guidance counselors' offices violated

Once school board determined that its public high the APA members' First Amendment rights. The

school students should learn about career and edu- district court held that the denial of access to bullet-

cational opportunities at “career day,” school board in boards, guidance counselors and Career Day was

could not exclude peace organization solely be- unconstitutional. The Board has only appealed the

cause it disagreed with association's views about district court's determination that several of the reg-

career choices students should make or because or- ulations concerning Career and Motivational Day

ganization disagreed with board's views regarding are unconstitutional.

military careers. U.S.C.A. Const.Amend. 1.

*1315 Thomas F. Homann, San Diego, Cal., for FN1. APA and several individual peace

amicus, COMD. activists brought an action for declaratory

and injunctive relief against Dr. Alonzo

Bruce H. Beerman, Fortson & White, Atlanta, Ga., Crim individually and in his official capa-

for CRIM. city as Superintendent of the Atlanta Pub-

lic Schools and the Atlanta Board of Edu-

G. Stephen Parker, SLF, Inc., Robert B. Baker, Jr.,

cation (Board). Jerome Harris has been

William O. Miller, Atlanta, Ga., for amicus, South-

substituted as a party for Dr. Alonzo Crim.

eastern Legal Foundation, Inc.

F.R.A.P. 43(c).

Ralph Goldberg, Atlanta, Ga., James H. Feldman,

Jr., Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors, FN2

*1316 I. FACTS

Philadelphia, Pa., for Searcey, et al.

Robert L. Barr, Jr., Jane Wilcox Swift, Asst. U.S. FN2. The facts of this case are set out in

Atty., Atlanta, Ga., John F. Cordes, U.S. Dept. of length in the district court opinions, Sear-

Justice, Appellate Staff, Civ. Div., Robert D. cey v. Crim, 681 F.Supp. 821

Kamershine, Washington, D.C., for U.S. (N.D.Ga.1988); Searcey v. Crim, 642

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 4

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

F.Supp. 313 (N.D.Ga.1986), and this referred to the two programs as one single

court's prior opinion. Searcey v. Crim, 815 event. Any reference in this opinion to Ca-

F.2d 1389 (11th Cir.1987). We summarize reer Day therefore includes both Career

the facts relevant to this appeal. Day and Motivational Day.

A major objective of the Atlanta School Board has FN4. When the APA first sought access to

been to improve the post-secondary opportunities Career Day, the Board's only official

available to its students, of whom 92% may be clas- policy stated that career education was ne-

sified as “minority” and 85% classified as “poor.” cessary to “enable [ ] students of all ages

The Board has created programs to motivate the to examine their attitudes, interests,

students to set career and educational goals and to aptitudes, and abilities in order to relate

inform the students of the opportunities that are them to career opportunities, and to make

available. The Board has involved the community valid decisions regarding further education

in two specific programs to accomplish these goals: and future endeavors.” D.Exh. 6.

Youth Motivation Day and Career Day. At Youth

Motivation Day, community members come into In February of 1983, the APA sent a letter to each

school to share their experience and to inspire stu- of the Atlanta high school principals requesting

dents to continue their education as the best means permission to place literature in guidance coun-

of achieving success. At Career Day, community selors' offices, to place advertisements in school

members speak with students about more specific newspapers and to appear at Career Days. They

job opportunities and the skills they need to attain submitted a plan to the Board but the Board took no

specific jobs. A major emphasis at both programs action. In the meantime, two high school principals

has been stressing the importance of finishing high accepted the literature. In June, 1983, the APA rep-

school and seeking further education or training resentatives met with then Superintendent Alonzo

after graduation. There is no set format to these Crim to discuss the APA's access to the school pro-

programs; some schools present several Career or grams. Dr. Crim agreed to distribute the materials

Motivational Days throughout the year and others to the guidance counselors, to allow the APA to set

FN3 up a table at Career Day, to make a list of APA

combine the two programs into one event.

Moreover, until the experience with the APA, the speakers available to the high schools, and to allow

School Board only had a general policy relating to the APA to place paid advertisements in the school

FN4 year books.

career education; it was left to the discretion

of each school principal to run the program as he or

After some publicity about Dr. Crim's agreement

she saw fit. Generally, a program would include a

with the APA, on October 4, 1983, the School

keynote speaker at an assembly, after which the stu-

Board reviewed Dr. Crim's decision and directed

dents would go to different classrooms to hear par-

him to deny APA all access to the schools. At the

ticular speakers. Often the speaker and the students

same time, the Board directed Dr. Crim to develop

would engage in a discussion in these smaller

a policy governing Career Days. In April 1984,

groups. Although the programs varied at each

however, the Board had not adopted any policy re-

school, one constant was that there were no restric-

garding Career Days and still completely barred the

tions as to the content of the speeches or discus-

APA from the schools. The APA then filed suit in

sions. See, e.g., Record, Vol. 9, at 234.

the district court contending that the School Board

FN3. Although some schools may have was violating their members' First Amendment

separate Career Day and Motivational Day rights. On August 13, 1986, the district court gran-

programs, all testimony in the district court ted partial summary judgment in favor of the

plaintiffs and entered a preliminary injunction pro-

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 5

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

hibiting the Board from denying the APA an oppor- policy. When the district court deferred ruling until

tunity substantially equal to that afforded to the the regulations were adopted, the Board adopted

military recruiters to participate in Career Days and Administrative Regulations to govern Career Days

place information on bulletin*1317 boards and in which are included as an appendix to this opinion.

FN5

guidance counselors offices. The Board filed an in- The regulations require an individual or group

terlocutory appeal and this court affirmed in part, who wishes to participate in Career Day to provide

vacated in part, and remanded for further proceed- sufficient information to the school principal to

ings. The case then proceeded to trial on the issue show that they will communicate information in

of whether the denial of access to Career Day and keeping with the goals of Career Day. If a school

bulletin boards and guidance counselor's offices principal denies a request to participate, the indi-

was unconstitutional. The district court found that vidual may appeal the denial to a Central Career

the bulletin boards and guidance counselor's offices Day Committee. The regulations also require parti-

were created public forums and that the Board had cipants to adhere to the regulations in their present-

not asserted a compelling interest justifying deny- ations. In the event that a participant violates a reg-

ing the APA access. The School Board has not ap- ulation, the Central Committee is authorized to im-

pealed that ruling. pose appropriate sanctions including barring that

individual or his group from further participation in

Prior to trial, at the urging of the district court, the Career Days.

Board adopted a uniform policy relating to Career

Day. The policy states that FN5. The court gave each party fifteen

days after the adoption of the regulations

The Board believes that schools should provide for comment.

educational programs that are pertinent to the prac-

tical aspects of post-secondary life and to the world The regulations also expand on the general policy

of work. The Board therefore supports “Career with respect to who may participate and what parti-

Day” programs as part of the general curriculum cipants may say: the regulations specifically inter-

programs for our schools. Career Day is to be a pro- pret the policy's requirement that participants have

gram which allows students to gain career aware- direct knowledge of the subject matter and present

ness and to explore career opportunities in various appropriate information. Regulation 9 interprets the

fields. Participants in “Career Day” programs shall “direct knowledge” requirement to include those in-

have direct knowledge of the career opportunities dividuals who by virtue of training, education or

about which they speak and shall be limited to experience possess information that would be use-

providing appropriate information about career ful to students in making career choices. However,

fields. Participants shall not be allowed to criticize Regulation 9 also requires each presenter to have

or denigrate the career opportunities provided by “some present affiliation or authority with that ca-

other participants. Written information about career reer field about which he or she is to make a

opportunities may also be made available to stu- presentation.” (emphasis added).

dents at school sites subject to the conditions im-

posed above. Restrictions may not be imposed on In addition, the regulations define “appropriate in-

the types of career opportunities in such material. formation” as information that is helpful to students

The Superintendent shall prepare appropriate ad- in explaining career options. Both the policy and

ministrative regulations for the implementation of regulations, however, specifically prohibit a parti-

this policy. cipant from criticizing or denigrating the opportun-

ities presented by other participants. The regula-

D. Exh. 5. By trial, however, the Board still had not tions specifically state that “information shall be

adopted administrative regulations to interpret the conveyed in as positive and encouraging a manner

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 6

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

as possible so as to be motivational to students.” contend that it may prevent the APA from present-

Reg. 10. Finally, presenters “whose primary focus ing information about peace oriented opportunities.

or emphasis is to discourage a student's participa- Instead, the Board challenges the district court's

tion in a particular career field” are *1318 totally conclusions that the direct knowledge, present affil-

prohibited from participating in Career Day. Regs. iation, no criticism and no discouragement regula-

10, 11. tions are unconstitutional.

On March 4, 1988, the district court entered a writ-

ten order finding that Career Day was a nonpublic II. DISCUSSION

forum, but that the direct knowledge requirement

and prohibition on criticism violated APA's first A. The law

amendment rights. The district court held that the

direct knowledge, present affiliation, and no criti-

cism regulations were unreasonable restrictions on [1][2] The Supreme Court has explained that the

access to Career Day. In addition, the court held type of restrictions which may be placed on First

that these regulations and the regulation banning Amendment activities depends in large part on “the

groups whose primary focus is to discourage stu- nature of the relevant forum.” Cornelius v. NAACP

dents from a particular field were unconstitutional Legal Defense Fund, 473 U.S. 788, 105 S.Ct. 3439,

because they were written with an intent to sup- 3448, 87 L.Ed.2d 567 (1985). In a traditional public

press APA's viewpoint. Thus, the court entered fi- forum and a “created” public forum, the govern-

nal judgment and a permanent injunction enjoining ment may enforce content based restrictions only if

the Board from denying the APA “an opportunity, necessary to serve a compelling state interest and

FN6

substantially equal to that afforded military recruit- narrowly tailored to serve that interest. The

ers, to present peace oriented education and career government may also enforce content neutral, i.e.,

opportunities to Atlanta public school students by time, place and manner regulations, which are nar-

... participating in Career Days and Youth Motiva- rowly tailored to serve a significant interest but still

tion Day programs.” More specifically, the court leave open ample alternative means of communica-

enjoined the Board from enforcing against the APA tions. Perry Education Ass'n v. Perry Local Educa-

the Career Day regulations to the extent that the tion Association, 460 U.S. 37, 45, 103 S.Ct. 948,

regulations 1) prevent APA from giving informa- 955, 74 L.Ed.2d 794 (1983); United States v. Bel-

tion of peace oriented education or career fields; 2) sky, 799 F.2d 1485, 1488 (11th Cir.1986). In a non-

require APA to have direct knowledge of the oppor- public forum, however, the government enjoys con-

tunities about which they speak; 3) prevent APA siderably more power over the use of its property: it

from criticizing or denigrating military careers; 4) may impose content based restrictions which are

require APA's primary focus not to be to discourage “reasonable and [are] not an effort to suppress ex-

students from participating in a particular field; and pression merely because public officials oppose the

5) require APA members to have a present affili- speaker's view.” Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 800, 105

ation with the fields about which they speak. The S.Ct. at 3448 (quoting Perry, 460 U.S. at 46, 103

School Board appealed. Since the APA does not S.Ct. at 955); Belsky, 799 F.2d at 1488; M.N.C.

challenge the district court's finding that Career Hinesville v. Department of Defense, 791 F.2d

Day is a nonpublic forum, the only issue presented 1466, 1474 (11th Cir.1986). The restrictions may

on appeal is whether specific aspects of the Career “be based on subject matter and speaker identity so

Day policy and administrative regulations are valid long as the distinctions are reasonable in light

regulations of First Amendment activity in a non- *1319 of the purposes served by the forum and are

public forum. More specifically, the Board does not viewpoint neutral.” Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 806, 105

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 7

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

S.Ct. at 3451. In this case, the Board's Career Day us, 473 U.S. at 811, 105 S.Ct. at 3453

policy and regulations will be upheld if they are (“reasonableness of the Government's restrictions

reasonable in light of the purposes of the forum and of access to a nonpublic forum must be assessed in

were not promulgated to suppress the viewpoint of light of the purpose of the forum and all the sur-

the APA. rounding circumstances”).

FN6. Traditional public forums are those FN7. Although the Hazelwood Court con-

areas such as streets and parks that “time cluded that school officials should have

out of mind, have been used for purposes great control over curricular expression,

of assembly, communicating thoughts that discussion was intended to exempt stu-

between citizens and discussing public dent expression in a curricular activity

questions.” Hague v. CIO, 307 U.S. 496, from the more stringent standard applied to

515, 59 S.Ct. 954, 964, 83 L.Ed. 1423 student speech in noncurricular activities

(1939). The government may also create a enunciated in Tinker v. Des Moines Inde-

limited or created public forum when it in- pendent School District, 393 U.S. 503, 89

tentionally opens a place or means of com- S.Ct. 733, 21 L.Ed.2d 731 (1969). In

munication to the public. Cornelius, 473 Tinker, the court held that a school may

U.S. at 802, 105 S.Ct. at 3449. not prohibit student expression unless it

will materially disrupt the operation of the

Before undertaking this analysis, it is necessary to school. Id. at 509, 89 S.Ct. at 738. There-

discuss an argument raised by the Board. The fore the emphasis in Hazelwood on control

School Board argues that Hazelwood School Dis- over curricular expression was intended to

trict v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260, 108 S.Ct. 562, 98 distinguish the case from Tinker and justi-

L.Ed.2d 592 (1988), changes the First Amendment fy the application of the Cornelius stand-

analysis applied to school officials' decisions relat- ard. Hazelwood, 484 U.S. at 271, 108 S.Ct.

ing to curricular programs. In Hazelwood, students at 570; see Alabama Student Party v. Stu-

sued when the principal refused to publish several dent Government Ass'n, 867 F.2d 1344,

articles in a school newspaper. Id. at 262, 108 S.Ct. 1345 (11th Cir.1989) (Cornelius standard

at 565. In upholding the school's actions, the Su- applicable to situation where outsiders

preme Court held that educators may exercise con- seek access to school).

trol over student expression in a curricular program

if the restrictions are “reasonably related to legitim- Of somewhat more concern is the sug-

ate pedagogical concerns.” 484 U.S. at 273, 108 gestion by the School Board that Hazel-

S.Ct. at 571. We fail to see how this standard dif- wood eliminates the requirement that re-

fers from the Cornelius standard for nonpublic for- strictions on speech in a curricular activ-

ums; instead it is merely an application of that ity be viewpoint neutral. Although the

standard to a curricular program. Since the purpose Supreme Court did not discuss viewpoint

of a curricular program is by definition neutrality in Hazelwood, there is no in-

“pedagogical,” the Cornelius standard requires that dication that the Court intended to

the regulations be reasonable in light of the pedago- drastically rewrite First Amendment law

gical purposes of the particular activity. Hazelwood to allow a school official to discriminate

therefore does not alter the test for reasonableness based on a speaker's views. As dis-

in a nonpublic forum such as a school but rather cussed, infra, Hazelwood acknowledges

provides the context in which the reasonableness of a school's ability to discriminate based

FN7

regulations should be considered. See Corneli- on content not viewpoint.

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 8

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

[3] A school serves an important function in our so- relate them to career opportunities, and to make

ciety: it serves as “a principal instrument in valid decisions regarding further education and fu-

awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing ture endeavors.” Def. Exh. 6. The more recent

him for later professional training, and in helping policy states that “Career Day is to be a program

him adjust normally to his environment.” Brown v. which allows students to gain career awareness and

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493, 74 S.Ct. to explore career opportunities in various fields.”

686, 691, 98 L.Ed. 873 (1954). Because of the spe- Finally, Dr. Crim summed up Career Day in his

cial role of schools in our society, the Supreme testimony by stating “[t]he focus that we have on

Court has allowed school officials to regulate Career Days is helping young people to make de-

speech based on content where such a regulation cisions as it relates to their occupational opportunit-

would not be upheld in a nonschool setting. Hazel- ies or post-secondary educational opportunities.”

wood, 484 U.S. at 271, 108 S.Ct. at 570; see Bethel Record, Vol 11, at 545. Thus, the primary purpose

School District v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675, 681, 106 of Career Day is informational; speakers inform the

S.Ct. 3159, 3164, 92 L.Ed.2d 549 (1986). In addi- students of the career and educational opportunities

tion, school officials may structure curricular pro- available to them. The speakers may talk about the

grams to “assure that participants learn whatever specific requirements of a certain educational pro-

lessons the activity is designed to teach.” Hazel- gram or job and/or the benefits of specific occupa-

wood, 484 U.S. at 271, 108 S.Ct. at 570. The Su- tions.

preme Court in Hazelwood reaffirmed that “the

education of the Nation's Youth is primarily the re- Because Career Day and Youth Motivation Day are

sponsibility of parents, teachers, and state and local often combined in a single activity, the program

school officials, and not of federal judges.” Id., at also has a second important goal, namely motivat-

273, 108 S.Ct. at 571. Thus, a court must defer to ing the students. As explained in the testimony of

reasonable educational decisions made by educat- Dr. Crim, the program also “is focused on raising

ors. However, when a particular decision implicat- youth expectations, providing them with the broad

ing the First Amendment “has no valid educational spectrum of what different kinds of occupations

purpose ... the First Amendment is so ‘directly and [there] are.” Record, Vol. 11, at 523-24. The type

sharply implicate[d]’ as to require *1320 judicial of motivation, like the type of information, which is

intervention.” Id. (citations omitted). With this con- appropriate depends on the circumstances of the

text in mind, we proceed to review the regulations students. Some students need information to make

at issue. First we examine the reasonableness of the the choice between particular educational opportun-

two sets of regulations. Then we review the district ities or jobs, while other students need motivation

court's finding that the regulations were adopted to to stay in school or find any job. Id. Thus, the or-

suppress the APA's viewpoint. ganization of Career Days and Motivation Days

was traditionally left to the discretion of the indi-

vidual schools. However, after the APA sought and

B. Reasonableness was denied access to Career Days and filed suit, the

Board adopted a more uniform policy regarding Ca-

Since Career Day is a nonpublic forum, any restric-

reer Days. The Board argues that the policy and the

tions on access must be reasonable in light of the

regulations are reasonable in light of the informa-

purposes of the forum. The educational purposes of

tional and motivational purposes of the program.

Career Day are evident both from the official policy

We address the reasonableness of the two sets of

and the testimony at trial. The initial Career Day

regulations in turn.

policy of 1977 states that the purpose of the pro-

gram is to enable students “to examine their atti-

tudes, interests, aptitudes and abilities in order to 1. The Direct Knowledge and Present Affiliation

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 9

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

Requirement. portance of the school's justifications, but whether

the regulations adopted are reasonable means to

Both the Career Day policy and the Administrative achieve these goals.

Regulations require that presenters have direct

knowledge of the career opportunities about which FN8. The United States intervened as a de-

they speak. Regulation 9 deems a presenter to have fendant in the district court on behalf of

direct knowledge “if by virtue of that person's train- the Armed Services. It initially filed a no-

ing, education or experience, the presenter pos- tice of appeal but voluntarily dismissed

sesses sufficient knowledge such that the informa- that notice of appeal. The government then

tion to be imparted would be of use and benefit to filed a brief as appellee in support of the

students in making their career choices and under- judgment below. The government argues

standing the career options available.” The regula- that although the district court erred in

tion goes on to require each participant to “have finding the regulations unreasonable, its

some present affiliation or authority with that ca- finding that the regulations were viewpoint

reer field about which he or she is to make a based is not clearly erroneous.

presentation.” The district court invalidated the dir-

ect knowledge requirement because it was inserted [4] We agree with the Board that the direct know-

to exclude the APA from appearing at Career Day ledge requirement is reasonably related to ensuring

and because the present affiliation requirement was that speakers present credible information and are

unreasonable. positive role models. It was reasonable for the

Board to conclude that individuals without any spe-

On appeal, the Board asserts that this requirement cific knowledge of career fields would not present

ensures that “a presenter knows what he is talking appropriate information. However, as stated by the

about,” which in turn ensures that the speaker gives APA in its brief, “[i]f the ‘direct knowledge’ re-

credible information and provides a credible role quirement meant only what the Board says it

model for the students. In addition, the *1321 gov- means, the APA would not have argued that it was

FN8

ernment argues that the requirement is justi- unreasonable. The APA is interested in students

fied as a reasonable means of avoiding political de- learning the truth about military service, and there-

bate at Career Day. Both these objectives are legit- fore has no quarrel with a rule requiring presenters

imate pedagogical concerns of the School Board. to know what they are talking about. The problem

Clearly it is vital to the success of the program that is that the Board's direct knowledge requirement in-

the speakers provide useful information and present cludes the requirement that the presenter also have

credible role models. In addition, school officials ‘some present affiliation with that career field.’ ”

are entitled to prohibit political or ideological de- Appellee's brief at 26-27 (citations omitted). It is

bate at Career Day. Because the program is a non- the present affiliation requirement that the district

public forum, it is appropriate for the school board court found unreasonable. We agree.

to make content based distinctions which serve an

educational purpose. The Board concluded that As the district court noted, the regulation as written

political debate is inconsistent with the purposes of would exclude retired persons and professional ca-

Career Day. See Regulation 13 (“It is the intent of reer counselors from participation in Career Day.

Atlanta Board of Education policy ... to preserve Since such individuals have participated in the past,

the character of the public school forum as primar- the School Board has acknowledged that they may

FN9

ily educational and not as a forum for public debate have valuable information for the students.

on matters of politics, social issues, or other contro- The Board advances no argument to support this

versial matters.”) But the question is not the im- regulation and thus points to no evidence in the re-

cord to explain the present affiliation requirement.

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 10

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

Nor can we discern how this regulation is related to onableness of principal's conclusions); Cornelius,

ensuring a successful Career Day. It is not intuit- 473 U.S. at 811, 105 S.Ct. at 3453 (discussing evid-

ively obvious that individuals who are no longer af- ence supporting reasonableness of conclusions). In-

filiated with a career would have less information deed the lack of any evidence to support this regu-

or would present a less effective role model; nor is lation and the facts surrounding the adoption of the

it obvious that such an individual would be more regulations support the inference that the regulation

likely to turn Career Day into a forum for his or her was written to specifically exclude the APA from

FN10

political views. Career Day. As explained above, the district court

was not clearly erroneous in finding that the School

FN9. We also note parenthetically that this Board intended to suppress the APA's viewpoint.

regulation could totally exclude the APA We therefore hold that although the requirement

from appearing at Career Day to speak that a presenter have direct knowledge is reason-

about peace oriented opportunities. Thus ably related to the purposes of the Career Day pro-

we find the Board's representation that it gram, the present affiliation requirement is unreas-

has no quarrel with the APA appearing for onable.

this purpose disingenuous.

FN11. In its reply brief, the appellant at-

FN10. For example, Dr. Foster, the Direct- tempts to explain its failure to present

or of Guidance Counselors, could not say evidence to justify the regulation by point-

whether a recently disabled veteran could ing out that the regulations were written

appear at Career Day to discuss the educa- after trial and the record was not reopened

tional benefits he received in the Army. for presentation of new evidence. This ar-

Record, Vol. 11, at 657-59. gument ignores the fact that the regulations

were only intended to interpret the general

Although the Board offers no support for this regu-

policy. In addition, the district court made

lation, the government argues that we must defer to

it clear that he could not rule without con-

the Board's decision. The government argues that

sidering the regulations. Thus the defend-

although the decision to exclude retired people

ants were on notice that they should

from Career Day may not be the wisest choice, a

present all evidence to support the direct

regulation “need only be reasonable; it need not be

knowledge requirement at trial.

the most reasonable or the only reasonable limita-

tion.” Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 808, 105 S.Ct. at 3452

. This argument wrongfully concludes that the regu- 2. The No Criticism and No Discouragement Re-

lation is reasonable and overstates the deference a quirements.

court must pay to School Board decisions. Al-

though the School Board has *1322 the discretion [5] The Career Day policy and Regulation 11 state

to choose between reasonable alternatives, there is that “[p]articipants shall not be allowed to criticize

no evidence that the Board made a choice in this or denigrate the career opportunities provided by

case. There is no evidence which even arguably ex- other participants.” The regulations go on to require

plains the Board's change in position; for example, that information be conveyed in a positive manner

there is no evidence that the Board had experienced so as to motivate the students. Under Regulations

any problems with individuals who were not affili- 10 and 11, “[n]o presenter whose primary focus or

ated with a group. We cannot infer the reasonable- emphasis is to discourage a student's participation

FN11 in a particular career field” may participate in Ca-

ness of a regulation from a vacant record. See

Hazelwood, 484 U.S. at 275 & n. 8, 108 S.Ct. at reer Day. The district court found the no criticism

572 & n. 8 (discussing testimony supporting reas- ban unreasonable because the school officials had

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 11

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

acknowledged the value of both positive and negat- ees, a soldier cannot quit. The testimony of Admiral

ive information to students making decisions about Larocque reiterates this obvious point. He testified,

their future. The court found the regulation prohib- “[t]he services would be stronger, we would have

iting participation of those whose primary focus is greater security as a nation if these young people

to discourage students from a particular field to be knew what they were getting into and then whole-

reasonable in light of the motivational purposes of heartedly supported it while they were in the ser-

the forum, but since the court found that all the reg- vice. Some people are simply not suited to military

ulations were written in order to suppress the APA's life, but it is too late to find out once you get in.”

viewpoint, even that regulation was unconstitution- Record, Vol. 8 at 111.

al.

On appeal the Board argues that the district court

The Board justifies both these regulations as reas- erroneously rejected its argument that negative in-

onably related to motivating the students to set formation might detract from the motivational pur-

goals. We agree that the regulation prohibiting a pose of the forum. The Board argues that both Dr.

group whose sole purpose is discouraging students Crim and Dr. Foster testified that the students

from an occupation or educational opportunity is would not be able to handle receiving both positive

reasonable. Discouraging students from participat- and negative information. See Record, Vol. 11, at

ing in a particular field clearly detracts from the 546-47; 642-43. The Board contends that this evid-

motivational purpose of the forum. It is the total ence supports the reasonableness of the decision to

banning of a group from the forum-rather than lim- ban criticism.

iting what a group can say-that we find to be un-

reasonable. We disagree. During cross-examination, both Dr.

Crim and Dr. Foster clarified their positions by stat-

As the district court noted, since the main purpose ing that students should receive factual information

of Career Day is to allow students to evaluate their about a job opportunity even if it were negative.

FN12

opportunities for the future, presenting only posit- On cross-examination, Dr. Crim revealed that

ive information directly conflicts with the educa- his real concerns about the students' ability to un-

tional purpose of the forum. The fact that speakers derstand the critical information was related to the

at previous Career Days have been able to criticize possibility that the information would be misused

the paths urged by other speakers reflects that the by speakers. First, Dr. Crim was concerned that al-

policy of the Board has always been, in the words lowing criticism would result in the discussion of

FN13

of Dr. Crim, “to provide [the students] with an op- controversial social issues at Career Day. As

timum level of information.” Record, Vol 11, at we held, supra, the Board can legitimately exclude

618. Both Dr. Crim and Dr. Foster, the Director of discussion of controversial matters from Career

the Guidance Counselors, testified that students Day. In doing so, the Board merely ensures that the

should receive as much factual information as pos- forum is used for its intended purpose-conveying

sible when making decisions about their future. Id. information about jobs and other opportunities.

at 548, 653. We agree with the district court that However, while avoiding controversial issues justi-

“[i]t is almost axiomatic that a valid decision is one fies prohibiting speakers from discussing the moral-

made after weighing pros and cons. Students cer- ity of war or defense spending, it does not justify

tainly cannot be expected to make important *1323 excluding bona fide negative facts which are relev-

career choices based only on positive information.” ant to the requirements or benefits of a specific job,

681 F.Supp. at 829. This applies with special force including one in the military. Dr. Crim acknow-

when one is making a decision about a career in the ledged this by agreeing that the APA or any group

military because unlike other dissatisfied employ- could tell the students (if it were documented) that

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 12

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

soldiers were underpaid. Dr. Crim stated, “That though Dr. Crim generally agreed that information

would be a fact related to the job benefits. Cer- contained in pamphlets prepared by the APA which

tainly, it would be appropriate to speak to pay and gives advice about the recruitment process was ap-

other work conditions and the like. Certainly, any propriate for students, he considered some of the

person representing any occupational organization statements in the pamphlet negative or pejorative.

would convey that kind of information.” Record, See Record Vol. 11, at 596-99, 610-12. This con-

Vol. 11, at 608. cern, however, does not justify a ban of all critical

information*1324 including the information Dr.

FN12. For example, Dr. Crim testified that Crim acknowledged was helpful to the students. In-

it would be appropriate for students to be stead, it justifies only prohibiting the use of critical

told (if it were true) that people in certain information to denigrate a profession and discour-

jobs were underpaid. Record, Vol. 11, at age students from that field. Finally, Dr. Crim was

608. Dr. Foster agreed that negative in- concerned that speakers would use negative factual

formation was valuable to the students information in a misleading or inaccurate manner.

when making decisions, but that the in- FN14

That concern, however, does not justify ban-

formation should be given to the students ning criticism entirely. Dr. Crim's concern about

by guidance counselors. If this were the perjorative information is addressed by the district

case, it would greatly enhance the reason- court's order, which allows the schools to exclude

ableness of the regulations. See Perry, 460 any inaccurate or misleading information from Ca-

U.S. at 53, 103 S.Ct. at 959 reer Day.

(reasonableness of limitation on access

supported by the substantial alternative FN14. When asked whether a presenter

channels that remain available for commu- could inform students that black and Lati-

nication). However, the testimony does not nos have less chances of getting a high-

reflect that guidance counselors are giving tech job in the military, Dr. Crim stated,

students this information. In fact, both Dr. “If anyone were to say that, and that is

Foster and Dr. Crim's testimony reveals documented by fact, that would be useful

that the workload of the typical guidance for the student.” Record, Vol. 11, at 617

counselor makes “it almost impossible for (emphasis added).

a counselor assigned 400 to one to have in-

dividual counseling with all students....” Thus, the regulations banning criticism are only

Record, Vol. 11, at 649. reasonable to the extent that they prohibit a group

from denigrating the opportunities offered by a spe-

FN13. For example, Dr. Crim agreed that cific group. The regulations are unreasonable to the

information about racism or sexism in the extent that they prohibit a group from presenting

military might be useful to the students but negative factual information about the disadvant-

that issue of that controversial nature ages of specific job opportunities because such in-

should be discussed in a more controlled formation is useful to students making decisions

and balanced setting such as a Social Stud- about careers. Moreover, the Board could not allow

ies class. Record, Vol. 11, at 607-08. speakers to point out the advantages of a particular

career but ban any speaker from pointing out the

Dr. Crim was also concerned that negative informa- disadvantages of the same career. That amounts to

tion could be conveyed in a pejorative manner to viewpoint-based discrimination which is prohibited

discourage students from considering certain fields. by the First Amendment regardless of the type of

If this were the case, it would clearly be at odds forum. We turn now to that issue.

with the purposes of Career Day. For example, al-

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 13

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

C. Viewpoint-based Discrimination pressed no viewpoint on disciplinary proceedings).

[6] “The existence of reasonable grounds for limit- The Board argues that Hazelwood does not prohibit

ing access to a nonpublic forum, however, will not school officials from engaging in viewpoint based

save a regulation that is in reality a facade for view- discrimination. We disagree. Hazelwood involved a

point-based discrimination.” Cornelius, 473 U.S. at content based distinction; the principal decided that

811, 105 S.Ct. at 3454. In a nonpublic forum, the the subject of teenage sexuality was inappropriate

government may limit the subject matter discussed for some of the younger students. Id. at 274-76, 108

by all speakers in a forum but it may not distinguish S.Ct. at 571-72. There was no indication that the

between particular speakers based on their view of principal *1325 was motivated by a disagreement

the approved subject matter. As the Cornelius with the views expressed in the articles. Although

Court stated “[a]lthough a speaker may be excluded Hazelwood provides reasons for allowing a school

from a nonpublic forum if he wishes to address a official to discriminate based on content, we do not

topic not encompassed within the purpose of the believe it offers any justification for allowing edu-

forum, ... or if he is not a member of the class of cators to discriminate based on viewpoint. The pro-

speakers for whose especial benefit the forum was hibition against viewpoint discrimination is firmly

created, ... the government violates the First embedded in first amendment analysis. Perry, 460

Amendment when it denies access to a speaker U.S. at 62, 103 S.Ct. at 964 (Brennan, J., dissent-

solely to suppress the point of view he espouses or ing). See, e.g., Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 812-13, 105

an otherwise includable subject.” 473 U.S. at 806, S.Ct. at 3454-55 (on remand, respondents free to ar-

105 S.Ct. at 3451; see also Perry, 460 U.S. at 62, gue that regulations were viewpoint based).

103 S.Ct. at 964 (Brennan, J., dissenting) (“We Without more explicit direction, we will continue to

have never held that government may allow discus- require school officials to make decisions relating

sion of a subject and then discriminate among to speech which are viewpoint neutral. See Virgil v.

viewpoints on that particular topic, even if the gov- School Board of Columbia County, 862 F.2d 1517,

ernment for certain reasons may entirely exclude 1522-23 & n. 6 (11th Cir.1989) (viewpoint neutral-

discussion of the subject from the forum.”) Thus, as ity test applies to First Amendment claim concern-

with any other nonpublic forum, once the School ing removal of books from curriculum).

Board determines that certain speech is appropriate

for its students, it may not discriminate between In this case, the School Board has determined that

speakers who will speak on the topic merely be- the students should learn about career and educa-

cause it disagrees with their views. Cornelius, 473 tional opportunities. Having done so, the Board

U.S. at 811, 105 S.Ct. at 3454; MNC, 791 F.2d at cannot exclude the APA solely because it disagreed

1475; see San Diego Committee Against Registra- with the APA's views about the career choices stu-

tion and the Draft v. Governing Bd. of Grossmont dents should make. More specifically, the Board

Union High School Dist., 790 F.2d 1471, 1581 (9th cannot exclude the APA because it disagreed with

Cir.1986) (by allowing military to place ads in its views about the military. The district court

school paper but not allowing ads by those opposed found that the Board was motivated by its disagree-

to military service, school officials engaged in ment with the APA's views. This finding of fact is

viewpoint discrimination); cf. Estiverne v. Louisi- only reversible if it is clearly erroneous. A finding

ana State Bar Ass'n, 863 F.2d 371, 382 n. 17 (5th is not clearly erroneous unless “the reviewing court

Cir.1989) (Bar Journal's refusal to print attorney's ... is left with a definite and firm conviction that a

version of disciplinary problem was content based mistake has been committed.” United States v.

restriction not viewpoint based since Journal pub- United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395, 68

lished no attorneys' responses and Journal ex- S.Ct. 525, 542, 92 L.Ed. 746 (1948). Moreover, the

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 14

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

finding is not clearly erroneous so long as “the dis- III. CONCLUSION

trict court's account of the evidence is plausible in

light of the record viewed in its entirety.” Anderson Plaintiffs were excluded from a forum established

v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564, 574, 105 S.Ct. by the Atlanta School Board for the purpose of en-

1504, 1511, 84 L.Ed.2d 518 (1985). couraging members of the public to participate in

Motivation and Career Days. The chief objective of

As the district court noted, there is no doubt that the Career Days was to inform students of the advant-

Board's abrupt change in policy was caused by the ages and disadvantages of various job and *1326

APA's request for access to schools. The procedure career opportunities. Plaintiffs' participation in the

by which the policy was adopted is an important forum was initially approved by then Superintend-

factor in deciding whether the Board engaged in ent of Schools Crim. Upon learning of this, the

viewpoint based discrimination. See MNC, 791 School Board denied plaintiffs access to the forum

F.2d at 1475. In this case, the Board's treatment of for the reason of plaintiffs' viewpoint toward the

the APA supports an inference that the Board inten- military.

ded to suppress the APA's views. In addition to the

evidence relied on by the district court, we note two After learning that the First Amendment permitted

additional factors which also support the district plaintiffs' involvement in the forum, the School

court's finding. First, one of the Board's justifica- Board adopted regulations governing content of

tions for limiting access-avoiding debate about con- speech and eligibility of speakers. The district court

troversial matters-although facially reasonable is correctly perceived that some of these regulations

capable of concealing bias towards the approach were designed to either directly or indirectly deny

advocated by specific speakers. If the School Board plaintiffs' participation in the forum. We affirm the

disagreed with the APA's views about careers, it district court's judgment with some slight modifica-

could easily label them “controversial” and thus ex- tions.

clude them from the program. See Cornelius, 473

With respect to Regulation 9, we reverse the district

U.S. at 812, 105 S.Ct. at 3454 (noting that facially

court's order insofar as it struck the entire regula-

reasonable justification of avoiding controversy is

tion. The first sentence which requires that the

capable of concealing viewpoint bias). In addition,

speakers have knowledge of the subject addressed

as we pointed out above, there are doubts as to the

is an appropriate content restriction. We agree with

genuineness of the Board's justifications based on

the district court that the “present affiliation” regu-

past practice. Cornelius, 473 U.S. at 812, 105 S.Ct.

lation is unduly restrictive and the district court's

at 3454; see Student Coalition for Peace v. Lower

striking of the last sentence of Regulation 9 is af-

Merion School, 776 F.2d 431, 437 (3d Cir.1985).

firmed.

For example, although the Board policy now es-

chews criticism of other participants and political The district court struck the last sentence in Regula-

debate, the record reflects that in addition to giving tion 10 (the no discouragement ban) and the first

their views about the path tosuccess, speakers have sentence of Regulation 11 (the no criticism, no den-

been free to criticize the approach advocated by igration ban). We affirm the district court with

other presenters and speakers have discussed such some modification, but agree with that court's reas-

controversial topics unrelated to job opportunities oning set forth at 681 F.Supp. 821, on page 829-30.

as defense spending without any censure. See, e.g., To the extent that a speaker is discouraging a stu-

Record, Vol. 9, at 232-34, 280; Vol. 10, at 365-66. dent from entering a specific career by providing

These factors strengthen the district court's finding students with valid and informative disadvantages

that the Board enacted these regulations to suppress of that career, this is appropriate and allowable. To

the APA's viewpoint. the extent a speaker discourages students from en-

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 15

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

tering a specific career by denigrating that career posed Career Day program offering. The request for

because of its nature or purpose of the career, the Career Day program participation may be denied by

administrator of the program can ban such speech. the school principal if curricular relevance is not

Stated another way, accurate information about a identifiable within the purpose/

career that some might take as criticism of the ca- goals/objectives/content of the program as presen-

reer or as discouragement of students from entering ted.

that career is permissible. On the contrary, ex-

hortative and denigrative presentations by speakers 4. In making the determination as to the curricular

for the purpose of denouncing certain careers for relevance of the proposed Career Day program

the purpose which they serve may properly be presentation, the school principal or his designee

banned. We do not believe the parties or any per- may request and review any written or printed in-

sons in the future who seek to participate in career formation which the presenter desires to distribute

programs can misunderstand what is and is not per- during the Career Day program. Principals are en-

missible. We affirm the district court's rulings with couraged to utilize the services of the school guid-

respect to Regulations 10 and 11, given the inter- ance counselor in making the determination of cur-

pretations herein made. ricular relevance and any necessary or desired re-

view or evaluation thereof.

In conclusion, we affirm the district court except

we reinstate the first sentence of Regulation 9, we *1327 5. Any organization wishing to participate in

reinstate the final sentence in Regulation 10, ex- a school's Career Day program must give sufficient

plain the limitations on “discourage” contained notice of that desired participation to the school

therein, and on the words “criticism” and principal such that staff/student orientation, super-

“denigrate” in Regulation 11. vision, scheduling and space can be arranged for

the Career Day program.

AFFIRMED AS MODIFIED.

6. Requests for Career Day program participation

are considered to be more timely when presented in

APPENDIX mid-August such that activities can be included in

the annual and/or guidance calendar.

CAREER DAY PROGRAM

7. Any person, firm, group or organization desiring

to participate in a school's Career Day program,

Administrative Regulations whose request for participation is denied by the

school principal, may appeal that denial of such

participation or any restrictions placed upon such

1. Any person, firm, group or organization wishing

participation by the school principal to a Central

to participate in the Career Day program should ini-

Career Day Committee to be chaired by the indi-

tiate its contact with the school principal.

vidual responsible at a central level for supervision

2. Any Career Day program or its presenter(s) must of school guidance counselors, presently the Co-

have the prior approval of the school principal. ordinator of Staff Support Services who is respons-

ible for guidance and counseling services. Any

3. Any person, firm, group or organization wishing party aggrieved by a principal's decision concerning

to participate in the school Career Day program Career Day participation may appeal such decision

must provide information to the school principal, in by filing a written request for appeal with the Co-

a form and format satisfactory to that principal, of ordinator of Staff Support Services who is respons-

the purpose/goals/objectives/content of the pro- ible for guidance and counseling services within ten

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 16

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

(10) days after notification of the principals' de- of that person's training, education or experience,

cision. Such appeal committee shall also consist of the presenter possesses sufficient knowledge such

one high school principal selected annually by the that the information to be imparted would be of use

committee chairperson and one guidance counselor and benefit to students in making their career

to be selected annually by the committee chairper- choice and in understanding the career options

son. Both the Assistant Superintendent for Cur- available. Each presenter and Career Day program

riculum and Research Services and the Director of participant shall have some present affiliation or

the Staff Support Services shall be ex officio mem- authority with that career field about which he or

bers of the Central Career Day (Appeal) Committee she is to make a presentation.

and shall be notified of and have the right to parti-

cipate in any pending appeal and the determination 10. Information concerning career fields shall be

thereof. In the event a member of the appeal com- deemed appropriate if it is in form and format such

mittee shall have made or participated in the de- that, in the opinion of the school principal, with ap-

cision appealed from, the chairperson may appoint propriate consideration given to the opinions and

a replacement member for purposes of the appeal. input from the school guidance counselor, the in-

Such appeal committee may review any document- formation is understandable by students and of use

ation concerning the request, may interview any to students in making career choice or in under-

witness or witnesses it deems appropriate and shall standing the career options available.*1328 Each

make its decision in writing within thirty (30) days participant shall be allowed to and expected to

after written appeal is filed with the Coordinator of provide full and complete, factual and objective in-

Staff Support Services. All interested parties shall formation about the applicable career field to stu-

be provided a copy of the decision of the appeal dents. Such information shall be conveyed in a pos-

committee. itive and encouraging a manner as possible so as to

be motivational to students. No presenter whose

8. Each person, group, firm or organization parti- primary focus or emphasis is to discourage a stu-

cipating in school Career Day programs shall be dent's participation in a particular career field shall

given a copy of the Atlanta Board of Education's be allowed to participate in school Career Day pro-

policy on “Career Day Program (Code IDD)” and grams.

these accompanying administrative regulations pri-

or to the program. Each participant shall be expec- 11. Participants in school Career Day programs

ted to follow the directives of such policy and ad- shall not be allowed to criticize or denigrate the ca-

ministrative regulations in its presentation to stu- reer opportunities provided by other participants.

dents. In the event any person, firm, group or or- Information provided to students at school Career

ganization shall violate the policy or these regula- Days shall be positive information regarding the ca-

tions, appropriate disciplinary action shall be im- reer opportunities available, shall motivate students

posed upon such participant by the Central Career to continue their education and to consider their

Day (Appeal) Committee, after appropriate review pursuit of the applicable career field and shall

and right of the offender to be heard, as it deems provide encouragement to students concerning the

appropriate, including the barring of that person's, career fields at issue. While participants are expec-

firm's, group's or organization's further participa- ted to provide full and complete, factual, objective

tion in school Career Day programs altogether. and accurate information concerning career fields

about which they speak, no participant whose

9. Presenters at a school Career Day program shall primary focus or emphasis is to discourage students

be deemed to have direct knowledge of the career from such career participation shall be allowed to

opportunities about which they speak if, by virtue participate. Encouraging student participation in a

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 17

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep. 1134

(Cite as: 888 F.2d 1314)

particular field, while in and of itself discouraging

participation in other career fields, shall not be

deemed to be criticism within the meaning of Board

policy or these regulations.

12. These regulations concerning Career Day pro-

gram materials shall apply both to oral presenta-

tions and to any written material to be distributed at

school Career Day.

13. It is the intent of Atlanta Board of Education

policy concerning Career Day programs and these

administrative regulations to preserve the character

of the public school forum as primarily educational

and not as a forum for public debate on matters of

policies, social issues, or other controversial mat-

ters.

C.A.11 (Ga.),1989.

Searcey v. Harris

888 F.2d 1314, 58 USLW 2337, 56 Ed. Law Rep.

1134

END OF DOCUMENT

© 2010 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

You might also like

- Lord's Day Act) or Its Effect (Often) Abridges A Charter RightDocument10 pagesLord's Day Act) or Its Effect (Often) Abridges A Charter RightBishop_HarrisLawyersNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules Bible readings and prayer in schools unconstitutionalDocument57 pagesSupreme Court rules Bible readings and prayer in schools unconstitutionaljooleeyenNo ratings yet

- Diabo Carleton Univ Presentation Feb 5 15Document53 pagesDiabo Carleton Univ Presentation Feb 5 15Russell DiaboNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 107.217.53.133 On Fri, 09 Sep 2022 13:26:13 UTCDocument140 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 107.217.53.133 On Fri, 09 Sep 2022 13:26:13 UTCF.E. Guerra-PujolNo ratings yet

- JONES v. OPELIKA 316 U.S. 584Document28 pagesJONES v. OPELIKA 316 U.S. 584Thalia SandersNo ratings yet

- Robert C. Marshall v. Douglas County School Board, Et Al.: Motion For Preliminary InjunctionDocument12 pagesRobert C. Marshall v. Douglas County School Board, Et Al.: Motion For Preliminary InjunctionMichael_Roberts2019No ratings yet

- BL (A) CK Tea Society v. City of Boston, 378 F.3d 8, 1st Cir. (2004)Document14 pagesBL (A) CK Tea Society v. City of Boston, 378 F.3d 8, 1st Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 13-4429 #80752Document58 pages13-4429 #80752Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- International Soc For Krishna Consciousness Inc V Lee - Proprietary Function of GovernmentDocument10 pagesInternational Soc For Krishna Consciousness Inc V Lee - Proprietary Function of GovernmentgoldilucksNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Troxel v. Granville 530 U.S. 57 120 ST. CT. 2054Document28 pagesTroxel v. Granville 530 U.S. 57 120 ST. CT. 2054Thalia Sanders100% (1)

- Miller v. Calif 413 U.S. 15, 93 S.ct. 2607Document26 pagesMiller v. Calif 413 U.S. 15, 93 S.ct. 2607Thalia SandersNo ratings yet

- Teachers and The Pledge of AllegianceDocument26 pagesTeachers and The Pledge of AllegianceKent HuffmanNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Thomas ConcurrenceDocument12 pagesThomas ConcurrenceLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Council of Buffalo v. Downtown DevelopmentDocument15 pagesCouncil of Buffalo v. Downtown Developmentpreston brownNo ratings yet

- Maryland Law Review Article Analyzes Whether Filing a Lis Pendens Triggers Due Process RightsDocument36 pagesMaryland Law Review Article Analyzes Whether Filing a Lis Pendens Triggers Due Process RightsHARESH SHAHNo ratings yet

- Donald H. Rumsfeld v. Forum For Academic and Institutional Rights, Cato Legal BriefsDocument28 pagesDonald H. Rumsfeld v. Forum For Academic and Institutional Rights, Cato Legal BriefsCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Kingston Sign Ban Lawsuit Dismissal DecisionDocument13 pagesKingston Sign Ban Lawsuit Dismissal DecisionDaily FreemanNo ratings yet

- AG OFOIA COMPLAINT CONCERNING CHARTER SCHOOL REFORM WORKING GROUPpinion No. 13-IB05 10.1.13Document11 pagesAG OFOIA COMPLAINT CONCERNING CHARTER SCHOOL REFORM WORKING GROUPpinion No. 13-IB05 10.1.13John AllisonNo ratings yet

- Capitol Square Review Bd. v. PinetteDocument8 pagesCapitol Square Review Bd. v. PinetteAntonio SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Robert C. Marshall v. Douglas County Board of Education: Response To Preliminary Injunction MotionDocument17 pagesRobert C. Marshall v. Douglas County Board of Education: Response To Preliminary Injunction MotionMichael_Roberts2019No ratings yet

- Gary R. Brown, Drew Terry, Michael Supan, Robert Brunckhorst, Julian P. Couch, David Dexter, and Michale Land, Donald R. Martin v. Virginia Opera Association, Inc., 698 F.2d 685, 4th Cir. (1983)Document2 pagesGary R. Brown, Drew Terry, Michael Supan, Robert Brunckhorst, Julian P. Couch, David Dexter, and Michale Land, Donald R. Martin v. Virginia Opera Association, Inc., 698 F.2d 685, 4th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Arthur Silva v. James T. Lynn, 482 F.2d 1282, 1st Cir. (1973)Document9 pagesArthur Silva v. James T. Lynn, 482 F.2d 1282, 1st Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Manhattan Community Access Corporation v. HalleckDocument25 pagesManhattan Community Access Corporation v. HalleckCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law Exam NotesDocument14 pagesAdministrative Law Exam NotesTess WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Judicial Protection of the Environment_ a New Role for Common-LawDocument21 pagesJudicial Protection of the Environment_ a New Role for Common-Lawramanmadahar87No ratings yet

- Supreme Court of The United States: No. 04-108 I TDocument17 pagesSupreme Court of The United States: No. 04-108 I Treasonorg100% (8)

- The Drexel Burnham Lambert Group Inc., Cross-Appellee v. A.W. Galadari and A.W. Galadari Commodities, Cross-Appellants, 777 F.2d 877, 2d Cir. (1985)Document6 pagesThe Drexel Burnham Lambert Group Inc., Cross-Appellee v. A.W. Galadari and A.W. Galadari Commodities, Cross-Appellants, 777 F.2d 877, 2d Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Procedural Impropriety II: Individual Rights and State DutiesDocument12 pagesProcedural Impropriety II: Individual Rights and State DutiesTanmay KHandelwalNo ratings yet

- Calvert Cliffs' Coord. Com. v. A. E. Com'n Environmental Impact RulingDocument64 pagesCalvert Cliffs' Coord. Com. v. A. E. Com'n Environmental Impact RulingMia VinuyaNo ratings yet

- The Long Island Radio Company, D/B/A All Shores Radio Company v. National Labor Relations Board, 841 F.2d 474, 2d Cir. (1988)Document6 pagesThe Long Island Radio Company, D/B/A All Shores Radio Company v. National Labor Relations Board, 841 F.2d 474, 2d Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. McLean Trucking Company, 834 F.2d 398, 4th Cir. (1987)Document8 pagesEqual Employment Opportunity Commission v. McLean Trucking Company, 834 F.2d 398, 4th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Decicco, 370 F.3d 206, 1st Cir. (2004)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Decicco, 370 F.3d 206, 1st Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - Conflict of LawsDocument8 pagesSyllabus - Conflict of LawsKathyrine BalacaocNo ratings yet

- Philippine Institute of ArbitratorsDocument68 pagesPhilippine Institute of ArbitratorsAnonymous 5k7iGyNo ratings yet

- Macasiano Vs National Housing Authority Davide Jr. July 1, 1993 MotionDocument5 pagesMacasiano Vs National Housing Authority Davide Jr. July 1, 1993 MotionCarlo MercadoNo ratings yet

- Howard Knopf ABC Presentation June 16 2023 Final ShowDocument45 pagesHoward Knopf ABC Presentation June 16 2023 Final ShowHoward KnopfNo ratings yet

- Procedural ImproprietyDocument4 pagesProcedural ImproprietyBaltranslNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument17 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dallas County Hospital District v. Dallas Association of Community Organizations For Reform Now, 459 U.S. 1052 (1982)Document3 pagesDallas County Hospital District v. Dallas Association of Community Organizations For Reform Now, 459 U.S. 1052 (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- McCullen - Citizens United Citations and SummariesDocument32 pagesMcCullen - Citizens United Citations and SummariesBrendan McNamaraNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Ultimate Cheat SheetDocument12 pagesConstitutional Ultimate Cheat SheetJosephNo ratings yet

- AMSCO - Chapter 7 - Individual Liberties - 2018Document10 pagesAMSCO - Chapter 7 - Individual Liberties - 2018Ava ShookNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Edison Co. v. Public Serv. Comm'n, 447 U.S. 530 (1980)Document23 pagesConsolidated Edison Co. v. Public Serv. Comm'n, 447 U.S. 530 (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Yale Law Journal Company, IncDocument21 pagesThe Yale Law Journal Company, IncMike BeckNo ratings yet

- In Re Alexander Grant & Co. Litigation, (Esm-1) - Appeal of News and Sun-Sentinel Co. and John Edwards, 820 F.2d 352, 11th Cir. (1987)Document10 pagesIn Re Alexander Grant & Co. Litigation, (Esm-1) - Appeal of News and Sun-Sentinel Co. and John Edwards, 820 F.2d 352, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Osediacz v. City of Cranston, 414 F.3d 136, 1st Cir. (2005)Document10 pagesOsediacz v. City of Cranston, 414 F.3d 136, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument19 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet