Professional Documents

Culture Documents

8 DB549 C7 D 01

Uploaded by

dang bui khueOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

8 DB549 C7 D 01

Uploaded by

dang bui khueCopyright:

Available Formats

The food security

challenge

Richard Gilmore and Barbara Huddleston

The article first describes current The question of international food security in the 1980s has moved from

market conditions and the nature concern over real shortages to recognition of a more complex set of issues

of the food security challenge they relating to use of surpluses for food security. In 1974, the global grain bin

present. Second, the article con- was nearly empty; today it is filled beyond capacity. Nevertheless,

siders the kinds of food security

developing country importers experiencing periodic crop reversals and

measures which have been or

having to satisfy growing demand remain preoccupied with securing their

could be taken with respect to

food resources over time at non-inflationary prices. Conversely,

improving LDC operations in com-

mercial grain markets, using producers burdened with surpluses in wheat and coarse grains and falling

reserves to achieve supply and farm income are waging a competitive effort to boost international prices.

price stabilization objectives and The USA, in particular, has returned to a system of production controls

making food aid a more effective and export incentives designed to reduce the margin between world

instrument for food security. supply and demand. If effective, heavy stock draw-downs and real

shortages could usher in a period of high prices once again,

Keywords: Food security; Grain notwithstanding increased production elsewhere.

markets; LDCs Current conditions offer a unique opportunity to use today’s surpluses

as the basis for new food security initiatives. Moreover, the international

Dr Gilmore is Managing Director,

food security debate of the 1980s is less one-sided than in the last decade.

Gilmore International Consulting,

Efficient producers are groping for an effective means of improving their

1225 Nineteenth Street, NW, Suite

806, Washington, DC 20036, USA return on production just as developing country importers are searching

(Tel: 202 822-9650). MS Huddleston is for a way to achieve access to supplies to cover their own immediate and

Research Fellow at the International longer-term deficits under an acceptable price threshold. Present market

Food Policy Research Institute, 1776 conditions could be conducive to a resolution of both elements of this

Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Wash- shared problem. The food security challenge of today and the near

ington, DC 20036, USA (Tel: 202 862- future, therefore, resides in designing the proper mix of market strategies

5600). and food aid and national stock initiatives whose success is as much

dependent on importing developing countries as traditional suppliers or

donors.

Current market conditions

World stock positions for wheat, coarse grains, oilseeds, and rice in

1982/83 are at record highs. World carryover stocks going into this

marketing year were almost 10% higher than the preceding year for

wheat and more than 7% greater for coarse grains. Early projections for

1982/83 showed roughly the same rate of increase. If realized, these

increases would widen the margin of supply over demand two years in

succession.

Notwithstanding a significant shortfall in Soviet production in 1981/82,

0306-9192/83/010031-15$3.00 0 1983 Butterworth & Co (Publishers) Ltd 31

The food security challenge

carryover stocks for the composite mix of grains and rice as of August

1982 represent 16% of expected utilization for the world as a whole

(excluding China), the highest since the early 1970s’ and well above the

10% level generally accepted as representing adequate security (see

Table l).*

Export prices not only reflect these stock accumulations but exceed

them in terms of the rate of depreciation. US wheat export prices were

down 13% and corn dropped roughly 20% by the end of the 1981/82

marketing year as compared to 1980/81 (see Figure 1). These declines

were repeated for every grain exporting country, but were particularly

dramatic for US varieties. Other important indicators showed similar

signs of a price slump. For instance, ocean freight rates on the tell-tale US

Gulf to Rotterdam route had reached $6.75 per ton as of 1 July 1982, the

lowest figure recorded since September 1978 for vessels in the 50000 ton

and over class. Declines were also registered on the lower volume routes

to developing countries, albeit at less dramatic levels than for the Gulf-

Atlantic shipping lane. When the effect of inflation on prices is taken into

account, the real decline in grain and transport prices since 1978 is even

more dramatic.

For many observers these indicators point not just to conditions of

global world food security but world food glut. There is a school of

thought which argues that actions on international food security and price

stabilization are irrelevant under present market conditions. Rather,

developing countries along with competing high-income importers can

cover their food deficits in the short and medium-term from existing food

supplies concentrated within the small exporter group of countries. There

Stock utilization ratios averaged 13% from are, moreover, untapped lines of credit which surplus producing

197!5-78, and 14% from 1979-82. countries are offering in their effort to promote additional foreign sales.

ZUSDA, Foreign Agricultural Circular,

Grains, 16 August 1982, p 2. When And prospects for other forms of export subsidy loom in the offing.3

Chinese stocks are included, the security There are those, of course, who recognize that there will continue to be

level has been estimated to be 17% and disparties in the allocation of these global food resources to individual

prevailing levels averaged 19% between

1977 and 1980 (Barbara Huddleston. Fiona countries. And some also perceive that the current position reflects not

Merry, Phil kaikes and Christopher only the ability of traditional exporters to continue increasing yields and

Stevens, ‘The EEC and third world food and expanding production, but also a slowdown in demand increases as

agriculture’, in Christopher Stevens, ed,

EEC and the Third World: A Survey 2, ODV recession spreads around the world. On both counts current market

IDS, London, 1982. conditions are therefore no cause for unmitigated optimism about

3The EC under its Common Agricultural resolving the dilemma of long-term international food security. Because

Policy offers exports of wheat and wheat

flour at subsidized prices in addition to food of the reduction in purchasing power caused by worldwide recession, the

aid grants. In October 1982, the USA drew paradox has been that today’s global food surpluses do not guarantee

from special export promotion funds to food security, even in the short-term. In addition, present conditions

provide interest free credits and govern-

ment guarantees under a new blended argue in favour of taking advantage of overproduction in key agricultural

credit programme. economies in conjunction with national agricultural development

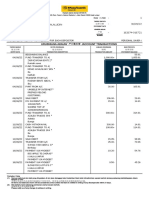

Table 1. Ending stocks position for wheat, coarse grains, and rice, 1974/75-1982/83 (projected).

Ending stocksa Change from StOCkS/USea

Maketing year as of 30 June previous year ratio

(July-June) World USA World USA world USA

1974/75 134.0 27.5 _ _ 10.9 19.4

1975/m 142.2 36.7 +0.33 +0.06 11.5 23.7

1976177 195.5 61.6 +0.68 +0.37 15.0 40.1

Note: aStocks data for world exclude China. 1977170 190.4 74.2 +0.20 PO.03 14.3 45.5

Sources: 1974/75-l 976/71- USDA World Agri- 1978179 218.4 72.3 +0.15 -0.02 15.3 40.0

cultural Outlook Board: 1977/7~1979/80 - lg7g/80 192.5 79.4 -0.12 +0.10 13.5 442

World Agricultural Supply and Demand jg80/81 180.4 62.1 -0.06 -0.22 12.4 36.4

Estimates. WASDE-107. USDA, 14 October I~AI/RP 217.4 90.7 +0.20 +0.59 14.8 54.3

1980; 1980/81-l 982/83 - World Agricultural 1982l83 (August

.Sup~ly and Demand Estimates, WASDE-137, projection) 238.0 125.4 +0.09 +0.23 16.1 67.2

USDA, 12 August 1982.

32 FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

240 .

- Nominal price (IWCindicator)

--- - Real price (1980 dolbrs - fob Atlontic parts.)

120

110

loo

Figure 1. Comparison of real and

nominal wheat prices.

strategies in poorer deficit countries to ensure a sustained period of food

security over the long run.

Nature of food security challenge

Short-term problems

First and foremost for the developing countries is the problem of

exchange rates and national balance of payments. Although the nominal

price of grains is down to its lowest point in three years, the dollar is at an

all-time high. With a high debt burden worsened by low, if not negative,

returns on raw materials and manufactured products from developing

countries, the latter have seen their potential gain from low world prices

quickly evaporate. Their currencies have depreciated relative to the US

dollar, sustained by high interest rates as opposed to real increments in

productivity. In 1981, African currencies depreciated on average by 29%

against the dollar, Latin American currencies by 18%,4 and Asian

currencies by 14%. As a result, the purchasing power of developing

countries has suffered, impeding access to foreign-origin food resources.

Paradoxically, the trough in international agricultural prices has also

made it more difficult for developing countries to pursue production

incentive policies, since the cost of these incentives rise as the dollar value

of domestic currencies and external prices fall. When international prices

are low because producers are accepting negative returns to capital, as is

now the case, the availability of cheap food imports represents a market

distortion, not a market efficiency. Under such circumstances, the argu-

ment that food aid can undermine the agricultural economies of aid

recipients also applies to that large grey area labelled commercial sales.

In addition, the price of inputs has increased worldwide, albeit at a faster

rate for capital than for labour intensive farming. Under these circum-

stances, total food production in developing countries is not expected to

4Excluding the Mexican peso, which has increase by more than 2% during the coming year,5 whereas consumption

experienced an effective devaluation to requirements will continue to grow at faster rates, along with population

date as high as 120% against the dollar. and income.

YJS Department of Agriculture, World food

Aid Needs and Availabilities, Washington, For developed countries, current conditions are equally problematic.

DC, 1982, p 2. Measures to curb production were introduced by the Reagan admini-

FOOD POLICY February 1983 33

The food security challenge

stration in 1981/82 in a vain effort to prevent budget costs for farm income

support programme from soaring out of sight. These measures provided

that only farmers participating in acreage reduction programmes desig-

nated for each crop could be eligible for deficiency and programme

support payments. Because of low prices, farmer enrolment for the first

year reached a national average of 81%) but final certified compliance for

wheat averaged 49% nationwide. The discrepancy can be attributed to a

widespread assessment by US farmers that government support pay-

ments accompanying participation in the acreage reduction programme

were not great enough to compensate for the lost revenue from reduced

production.

Despite the negligible effect of last year’s programme, increased parti-

cipation in 1982/83 is likely due to extremely low market prices for wheat

and feedgrains, and the new paid land diversion programme plus higher

loan rates on wheat and corn legislated by Congress during the debate on

farm legislation shortly before the fall elections. If effective, the measures

would reduce the size of surplus stocks held in US grain elevators and

push market prices above the levels which trigger income support pay-

ments by the US Treasury. As long as world stocks remain above the food

security level, there is little prospect that production cutbacks will cause a

significant increase in prices. However, as the stock/utilization ratio

drops below the safety margin, prices start to move up, rising at a faster

rate the more the ratio declines.6

While the estimated stock/utilization ratio in the USA came to 41% for

wheat and corn before the new US legislation was passed, estimates for

the impact of combined land diversion payments and voluntary acreage

reductions at 20% of base acreage for wheat and 15% for corn suggest

ending stocks could fall by as much as 21.2 million tons for these two crops

alone. This could reduce the total stock/utilization ratio to about 36%,

and cause farm prices to rise to about $3.60 per bushel for wheat and

$2.90 for corn.’ If there is massive Soviet buying in response to sup-

posedly poor harvests during 1982/83, these price increases could be even

greater, with adverse consequences for developing country importers.

The immediate dilemma for developed countries is that programmes

which rationalize domestic production and stock outcomes may in-

advertently work against food security and price stabilization objectives

for developing countries. On the other hand, if production is not curtailed

and stocks are allowed to increase indefinitely, the rock bottom world

market prices may force the USA and other exporters into dumping their

surpluses in ways which work against the long-run production goals of

developing country importers.

Long-term challenge

6Barbara Huddleston, D. Gale Johnson,

Shlomo Reutlinger, and Albert0 Valdes, While it is convenient to attribute responsibility for international food

International Finance for Food Security, security to the USA because of its dominant supply position,8 other

World Bank monograph, Johns Hopkins developed coutries also pursue policies with more adverse effects on

University Press, Baltimore, MD, forth-

coming. world market stability. In fact, US policies traditionally have been pre-

7Figures derived from Congressional dicated on the notion that retention of a relatively open market system

Budget Office, Staff Working Paper on Paid will have a more stabilizing effect as consumption increases worldwide

Acreage Diversion Program, 24 June 1982.

*For 1982/83. US wheat production is than a managed market system. Moreover, the comparatively large uti-

estimated at 18% of total world production lization base within the USA is more likely to endure lower export prices

and exports at 48% of estimated world for agricultural commodities than competing surplus producers. Thus US

trade; for feedgrains the estimated per-

centages are 30% of world production and supplies are generally marketed at low prices compared with other sup-

84% of world trade. plies during surplus production periods. Under these circumstances, the

34 FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

US market is more accessible over time to developing country importers

from the standpoint of commercial exports as well as concessional food

transfers than most other suppliers.

By comparison, other importing and exporting countries contribute

significantly to contemporary trends of price instability and supply uncer-

tainties. The European Community (EC) is an example of a highly

protected agricultural economy with inherent costs and benefits. Its

impact on food deficit developing countries is increasingly important due

to the fact that the EC now is the world’s third largest wheat exporter and

that the availability and value of these supplies are artifically determined.

With a levy/export subsidy system at work, agricultural prices and

volumes are determined as a function of internal political and economic

conditions rather than international supply and demand considerations.

As a result, the EC does not offer the benefits of a consistent residual

supplier for developing countries. Its pricing policies and regulated trade

flows can undermine agricultural development plans in these countries

and can inspire retaliatory actions on the part of competing suppliers

which compound the problem. The likelihood of this outcome is all the

more probable in a market where international commodity prices are

below an average positive rate of return on production.

In this case, surplus countries will seek every means possible to export a

portion of their excess supplies. The EC system automatically raises its

import levy as the spread between low international prices and higher EC

prices widens. The resulting surplus production is partially drawn down

through exports, introducing more supplies on the world market, and

thus, depressing prices even further. Although favourable in the short

term for LDC buyers, the longer-term consequences are likely to under-

mine these countries’ pricing policies and agricultural production goals.

Importers seeking to stabilize their own internal agricultural eco-

nomies through highly protectionist devices must share in this respon-

sibility of exporting a higher form of instability often thrown into the laps

of the most vulnerable developing countries. Japan is a case in point as is

the USSR. In both cases, their import levels are less a function of

international prices than domestic policies defining utilization require-

ments.9 These countries tend to introduce a range of uncertainties into

the market which defy a development planner’s efforts to hedge con-

structively against such risks. In times of scarcity, these countries are

assured preferential access to foreign food resources by the sheer weight

of their unassailable purchasing power.

Food aid is a collateral problem in terms of its destabilizing effects as

administered by donor countries. Concessional and grant assistance is

generally linked with a donor’s annual economic performance and

foreign policy objectives. In the absence of long-term commitments, food

aid flows are at best indeterminate and cannot be factored into an aid

recipient’s national account until their atual fulfilment. In many

instances, the concessional corridor mirrors the recurrent problems of the

commercial sector, both of which are run at the sufferance of political and

economic vicissitudes independent of any immediate or long-term food

requirements in developing countries.

The private sector can also detract from the achievement of a workable

state of price stabilization and food security for individual developing - _

countries. The role of many of the largest-international grain trading

9Japan’s Food Agency has jurisdiction over

import levels and wholesale pricing for houses is more perplexing than government’s in that it is harder to

wheat and barley. discern. There are a host of efficiencies which accompany certain

FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

economies of scale and commercial technologies which at least six of

these companies embody. lo On the other hand, there are less

distinguishable inefficiencies rooted in their oligopolistic structure. In

theory, developing countries, just like other importers, can select out the

inefficiencies, but their market power is such that instances are rare

where the opportunities arise. Moreover, the profitability of the grain

trading companies rests on the following essential components which

often work at cross purposes with food security and price stabilization

objectives:

0 High volume sales and rapid turnover in handling.

0 Multilateral sourcing to secure grain access from principal supply

origins.

0 Price movements within widely fluctuating price bands.

0 Supply uncertainties.

0 Large-lot transactions delivered in large vessels.

l Active hedging operations.

0 Vertically and horizontally integrated operations in supplying and

importing countries.

To minimize disparities in the allocation of global food resources to

individual countries and maximize countries’ ability to take advantage of

variable market conditions, one argument runs that multilaterally-

secured trade liberalization can do more for world food security than

international food reserve initiatives .l* Three major exporters, the USA,

Canada, and Australia have disavowed past efforts to establish a

multilateral reserve system on the grounds that the market and current

economic conditions can achieve the same objectives more effectively. A

collateral to this policy is an increased emphasis on encouraging

developing countries to achieve food self-reliance through production

and consumption efficiencies obtained by giving domestic markets

greater flexibility.

Another view put forward by the Secretariat of the World Food

Council for consideration by the Eighth Ministerial Meeting in June 1982

asserts that the current market glut is temporary, and that this is an ideal

time for countries to join in negotiating an agreement which would

remove up to 10 million tons of grain from the market and create a reserve

from which developing countries could draw when the market tightens

again.12 There certainly is evidence to suggest that existing marketing

systems are not adequate to ensure international food security for all

countries alike, even though available supplies currently appear

excessive. However, it would be a mistake to conclude from this that the

answer lies in the revival of old solutions. That present conditions do not

relieve basic food concerns of developing countries is not to suggest that

the remedy lies either with elaborate multilateral schemes or through a

pure laissez-faire approach to the problem. There is a better way to join

the debate, deriving distinct benefits from both positions.

Ttichard Gilmore, A Poor Harvest: The

Clash of Policies and Interests in the Grain Clearly what is needed, then, is a realistic approach to international

Trade, Longman, New York, 1982. food security which will allow developing countries to take advantage of

“Robert Paarlberg, ‘A food security global supply fluctuations in ways which neither strain their limited

approach for the 1980s: righting the

balance’, Agenda 1982, Overseas Deve- foreign exchange resources nor work to the disadvantage of their

lopment Council, pp 89-95. domestic production strategies. Some food security measures have

lZWorld Food Council, World Food Security already been adopted by national governments and international

and Market Stability: A Developing

Country-Owned Reserve, WFC/1982/5, organizations which respond to these concerns; yet other practical steps

Rome, March 1982. could be taken at relatively low political cost for both exporters and

FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

importers. These measures may be grouped under three headings: those

which improve the capacity of LDC importers to operate efficiently in

commercial grain markets; those which contribute to supply and price

stabilization in both domestic and international markets; and, those

which enhance the effectiveness of food aid as a food security resource for

low-income countries. The remainder of this article deals with each of

these in turn, discussing first the likely impact of measures which have

already been taken and then the merit of proposals for further action.

Operations in commercial grain markets

As already noted, the absence of food security for developing countries in

today’s market is defined mainly in terms of financing, exchange rates,

knowledge-intensive skills, and handling-related concerns. Despite the

increased availability of favourable exporter credit in times of surplus,

financing is a persistent problem for a range of developing country

borrowers faced with a disequilibrium in their balance-of-payments. The

credit crunch becomes even more serious in times of shortage when

exporter subsidies dry up and world prices rise.

To alleviate both problems and make it possible for developing

countries to finance commercial purchases regardless of world market

conditions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently extended

the coverage of its Compensatory Financing Facility to include above-

trend costs of cereal imports. This permits countries to borrow from Fund

resources in an amount equal to the excess cost of cereal imports above

the trend value for a given year, unless this excess cost is offset by

above-trend export earnings. The credit is offered at favourable interest

rates, but must be paid back within three years. Since the facility’s

purpose is to permit countries to manage the financing of commercial

cereal imports with greater ease, it will benefit primarily those countries

which purchase sizeable quantities of cereals commercially from time to

time. I3

Low-income countries do not usually fall in this category, as they can

seldom afford to import cereals except with highly concessional assist-

ance. In 1974-78 for example, middle and high-income countries

imported an average of 48.8 million tonnes commercially per year and

received 3.5 million tonnes of food aid, whereas low-income countries

imported 6.7 million tonnes commercially and received 4.3 million tonnes

of food aid.14 On a per capita basis, middle and high-income countries

took 28.6 tonnes per thousand persons commercially and 2.0 tonnes in

food aid in 1976-78, while low-income countries took 5.5 and 3.6 tonnes

respectively. Low-income countries may be forced to use the facility in

particularly difficult years if no other source of assistance is available, but

for them the three-year repayment period merely postpones the inevit-

able strain which their commercial purchases will create when the pay-

ments become due. This drawback also applies to existing credit

programmes offered by exporting countries. For middle and high-income

countries, by contrast, the availability of IMF and other credit enables

them to cope efficiently with temporary balance of payments problems

caused by fluctuations in the amounts and prices of their cereal imports.

What these countries all share, however, is the need to refine their

13Huddteston,et a/, op tit, Ref 6. procurement technologies. Food aid recipients and commercial buyers

‘4BarbaraHuddleston, Closing the Cereals

Gap with Trade and Food Aid, IFPRI, alike must enter into the world market to cover their import requirements

Washington,DC,forthcoming. in competition with such importers as Japan, the EC, and the Soviet

FOOD POLICY February 1983 37

The food security challenge

Union, which dominate the market. Not only can they maximize their

savings through certain efficiencies, but they can also enhance their food

security by introducing appropriate commercial reforms. In so doing,

they can purchase in advance of their immediate consumption

requirements to account for favourable seasonal trends, money market

developments, transportation costs, and other relevant indicators.

Food security requires maximum flexibility in responding to varying

economic and social conditions, and commercial sophistication for LDC

importers facilitates this adaptation process. The problem is that many

such importers have not succeeded in introducing the requisite reforms to

take advantage of existing market opportunities. The problem is com-

pounded by the structure of the market and the failure of many countries

to recognize resulting obstacles which LDCs must strive to overcome.

Although they are becoming increasingly important buyers as a group,

the participation of individual developing countries in the grain trade is

still quite limited, because of certain structural and procedural

characteristics:

0 Absence of adequate price, supply, and commercial information and

analysis to assess significant market developments.

0 Government-run import/buying agency monopolies.

0 Relative scarcity of foreign exchange.

0 Higher commercial risk for LDCs.

0 Relative decline of food aid.

0 Small-scale purchases of foreign-origin grains, rice, and pulses.

0 Importing for immediate consumption requirements.

0 Low-grade port/internal handling, storage, and distribution facili-

ties.

0 Traditional consumer preferences.

0 Graft.

This same group of countries also shares a common opportunity. With

global supplies of all cereals at record levels, and hence, real prices below

the cost of production in even the most efficient producing countries,

LDC buyers that initiate certain reforms now can stretch a windfall profit

into a long-term gain. In general, the degree of loss or gain will depend on

the extent of reform appropriate for each country.

At a minimum, most LDCs have come to accept the need to plan major

purchases one year in advance to obtain negotiating flexibility and avoid

inefficient, unpredictable deliveries. Demurrage charges, delays in

discharges, cargo deterioration, and other costs are too great for LDC

governments to neglect an annual import review process at the

interministerial level. In addition, LDCs should consider relaxing tender

procedures, particularly for emergency purchases which will inevitably

be needed in some years. By giving the shipper opportunity to fix freight

and insurance charges at the time of sale, excess margins to cover the

seller’s risk can be avoided, with savings of up to 10 to 15% of the value of

the contract. l5

As already noted, LDC importers pay a substantial premium for their

habit of being spot buyers. To regain an acceptable level of market

control, they must achieve a greater degree of flexibility. For many

‘5World Food Council, Procurement Prac- countries a form of forward contracting may not be the answer, but larger

tices and Alternative Import Strategies for working stocks are. It is not suggested that at this stage individual LDCs

Developing Countries; Gilmore- Inter-

national Consulting, 13 January 1982, attempt to store enough grain to cover annual utilization requirements.

WFC/1982/5/Add 1. Rather, it would be sufficient to think in terms of 2-3 months of stock in

FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

the pipeline with another 2 months in storage (varying to an extent on a

case-by-case basis). This amount would ensure uninterrupted

distribution and a small buffer stock. If they act under current market

conditions, LDCs could buy grains at non-inflationary prices and obtain

the prerequisite level of flexibility to operate as futures buyers on the

open world market.

For those countries lacking suitable storage facilities, their forward

purchases would have to be held in the form of futures contracts.

Inventories stored in a neighbouring country might be preferable from a

food security standpoint, but less practical for political reasons. These

countries could also store their reserves in the supplying country, but

carrying costs, freight questions, and a level of political uncertainty might

make this option less attractive.

Use of reserves for supply and price stabilization

The question of appropriate reserve policy at both national and inter-

national levels is an important aspect of food security. For developing

countries the issues are the amount of stocks needed at different times of

the year to assure supply and price stability throughout each marketing

season, the amount of stocks needed as a reserve against occasional

emergencies, and the kind of international stabilization agreement, if

any, which merits support. For developed countries the issues are the

kind of support required by developing countries for improving their

national stocks programmes, the role of exporter stocks in assuring

international supply and price stability from year to year, and the kind of

international stabilization agreement, if any, which merits support.

National stocks programmes in developing countries

Since 1974, a number of developing countries have received assistance for

creation of reserve stocks under the auspices of the FAO Undertaking on

World Food Security and the FAO Food Security Assistance Scheme.

Much of this assistance has been intended for buffer stocks to safeguard

against unusual emergencies. Unfortunately, this approach did not take

into account the need to improve management of working stocks in many

countries as a precondition for designating some portion of these stocks

as a food security reserve.

Sound management of domestic price and procurement policies will

necessitate accumulation of larger working stocks in many developing

countries. Incentive prices for farmers will inevitably produce surpluses

in some years, and the government will have no choice but to purchase

and store these surpluses consistent with its overall pricing and pro-

duction goals. At the moment, however, many government purchasing

agencies are ill prepared to handle this eventuality, either from the

standpoint of financing stock accumulation or of managing the physical

stocks.16 Imports are the other side of the stock building and manage-

ment equation. Efficient procurement and handling technologies will

assist in reducing the costs of carrying stocks and permit better allocation

of foreign-source grain through domestic distribution channels.

Bilateral and multilateral donors have increasingly recognized that

Wheryl Christensen, ‘Emerging food much of their assistance must be used for necessary improvements in

problem and policy responses in Africa’, storage and marketing systems before it can be directed to creation of

Paper presented to American Agricultural

Economics Association, Logan, UT, August reserves. In this connection. the International Wheat Council has con-

1982. sidered whether to create a special subcommittee to evaluate foreign

FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

assistance flows for stock creation in developing countries. If established,

this committee would serve as a forum for coordinating allocation of both

food aid and financing to create such stocks, irrespective of whether the

intended purpose was to improve market management or create true

food security reserves. l7 This idea was set aside when negotiations for a

new International Wheat Agreement broke down in 1979, but it deserves

further consideration on its own merit, possibly as a new provision of the

next Food Aid Convention or as a new activity for the governing body of

the World Food Programme.

Existing exporter reserves

Partly for domestic policy reasons and partly to respond to international

pressure following the 1974 World Food Conference, the USA adopted a

unilateral reserve policy in its 1977 farm legislation. Crops held in reserve

in the USA have traditionally been acquired by the Commodity Credit

Corporation (CCC) as payment for non-recourse loans by producers.

The new law established farmer-owned reserves (FOR) for which storage

subsidies are paid, providing farmers agree not to release stocks unless

prices reach fixed levels which are anywhere between 20 and 35% above

the current market price, depending on the crop. Unlike CCC-held

stocks, these reserves are not working stocks in the sense of their being

readily accessible for domestic or foreign purchase. The primary purpose

of the programme, indeed, is to raise domestic, and hence, international

prices by isolating a fixed portion of supply from the market when world

prices are low.

A secondary purpose is to provide a backstop to international food

security by giving farmers incentives to release stocks and by drawing out

private stocks as prices rise. In fact, application of the programme under

the Carter administration served to introduce more price instability and

uncertainty than in its earlier absence. l8 This is because farmers tended

to unload stocks in spurts as prices climbed towards the release trigger,

causing rapid shifts in marketings and sharp fluctuations in price. The

programme has not been tested in a true food emergency however, but

certain modifications in the programme offer the prospect of correcting

such destabilizing effects.

The economic argument for creating the farmer-held reserve was that

when world prices are low, exporters must build up stocks or pay farmers

to take land out of production, either of which represents an unavoidable

cost for their domestic farm programmes. The effect during low price

periods should be to reduce somewhat the size of effectively available

stocks by isolating a portion of production under the FOR programme,

thereby triggering some increase in price for a given ratio of world stocks

to world consumption. This benefits producers and reduces the cost of

domestic farm programmes in exporting countries, while increasing the

cost of cereal purchases for importing countries. However, as the world

price approaches the trigger for releasing stocks, release of privately-held

stocks could be expected in advance of release of stocks from the reserve,

and the effects of both actions together would dampen price increases and

encourage more consumption than if no stocks had been set aside. This

“As noted earlier, some developing

countries may find it desirable to create benefits consumers in all countries either directly or through reduction in

some stocks over and above the normal the cost of imported cereals for governments which subsidize domestic

needs of the market, particularly if they are f oo d prices. Thus unilateral reserves in exporting countries, if properly

regular importers and need to assure un-

interrupted supply. managed, can contribute simultaneously to domestic goals and world

‘*Gilmore, op tit, Ref 10. food security.

40 FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

Current multilateral reserve proposals

Similar arguments have been used to defend the idea of a multilateral

reserve held by and designated only for developing countries. The World

Food Council proposal of June 1982 called for negotiation of a buffer stock

agreement which would qualify for assistance under the IMF Buffer

Stock Facility. l9 Such an agreement would provide for buffer stock

purchases by developing countries in amounts up to one year’s normal

import requirement. The IMF would finance these purchases at 6.5%

over a three-year period. In addition, developed countries would be

asked to subsidize all or part of the storage costs for countries requiring

such assistance. The agreement would establish acquisition and release

prices, but might provide for early release for countries willing to repay

the storage and interest subsidies obtained as a result of participation in

the agreement.

A reserve agreement along the lines proposed could be useful to

developing countries if the exporters agree to pay the cost of storage as a

cost attributable to domestic farm programmes, if the reserve is created

through stock purchases by developing countries at subsidized interest

rates, and if the price range is low enough to assure acquisition and

release at prices favourable to LDC interests. However, it is not clear that

a reserve agreement providing equitable benefits to both developed and

developing country participants is negotiable.20

Fixing a satisfactory price band for a multilateral agreement poses

many problems. It is in the nature of such agreements that the stock

acquisition and release prices be relatively automatic. If the acquisition

price is too low, countries run the risk that the market will not drop to the

level necessary to permit stock acquisition. If the acquisition price is too

high, the benefits to participants are reduced because of the higher cost of

acquiring stocks. Similarly, if the release price is too low, stocks may be

drawn down prematurely from the standpoint of food security and

exporters may face depressed market prices even though current harvests

are below normal. But if the release price is set too high, developing

countries may not be able to get access to their own reserve stocks in years

when domestic production conditions require extra imports.

A second set of problems relate to the uncertainty about how often

reserve stocks created by a multilateral agreement would actually be

needed. The cost effectiveness of holding stocks depends on the length of

time the stocks are held, the differential between the purchase and sale

19WorldFood Council, op cit. Ref 12. value of the grain, secondary price effects on cash and futures markets,

Z”While recognizing the need for food and rates of inflation, interest, and monetary exchange. The longer

security preparedness in the event of

another period of worldwide scarcity and

stocks are held, the less likely it is that the final sale price will fully cover

high prices, ministers participating in the the storage and interest costs of holding the grain.

June meeting of the World Food Council A number of analysts have demonstrated that a period of high prices

concluded that this proposal required

further study and elaboration before a

similar to that which occurred in 1973-75 could be expected at least once

decision could be taken to proceed with every decade if historical patterns repeat themselves.21 On this basis it is

negotiations. In the WFC’s subsequent often assumed that reservk stocks wduld be needed frequently enough to

report to the Second Committee of the UN

General Assembly, modifications were

avoid the excessive cost associated with long-term holding. However,

proposed which would remove the uniform past experience indicates that while this factor has an important bearing

release price provisions entirely in an effort on the outcome as to cost-effectiveness of a reserve, there is no certainty

to make the reserve more responsive to

about the number of years which will intervene between a low price and

individual LDC food security requirements.

*‘James P. Houck and Man/ E. Rvan. high mice vear.

Economic Research on lntem&ional drain ko; developing countries there is some risk in participating in a multi-

Reserves: The State of Knowledge, Bulle-

tin 532-1979, University of Minnesota, lateral reserve agreement, even under the favourable conditions pro-

Agricultural Experiment Station, 1979. posed to the World Food Council. Depending on the level of acquisition

FOOD POLICY February 1983 41

The food security challenge

and release prices established by the agreement, a country could find that

the cost of carrying a reserve stock exceeds the value of the stock at the

fixed release price within three to five years after acquisitions.22 If the

country also has to pay some part of the storage cost, the time period

during which stocks can be economically held will be even’shorter. Other

uncertainties relate to future interest rates, currency exchange rates, and

shipping and handling conditions.

From the developed country perspective, unilateral reserves as an

adjunct of domestic farm support programmes may make some sense, but

it is not clear that a multilateral reserve agreement subsidized through the

IMF and bilateral storage grants is equally advantageous. In a unilateral

programme, the country holding the stocks takes a risk that its costs will

not be fully recovered, and if necessary it sets this off as a cost of farm

income support. However, it also retains the possibility of gain from the

operation of its reserve programme. In a multilateral reserve arrange-

ment subsidized by exporters, the exporters would be transferring this

possibility of gain to the developing country stockholders participating in

the agreement.

As pointed out above, donor support for grain storage and marketing

programmes in individual developing countries is clearly desirable. How-

ever, assistance for a multilateral reserve arrangement will reduce donor

flexibility in managing their own farm programmes in return for an

arrangement in which the gain to intended beneficiaries is not assured.

Moreover, a developing country reserve styled after the FOR in the USA

is not likely to translate into appreciable gains for growers in the USA.

The effect on price is hard to calculate because of the relatively large size

of the proposed reserve (9-12 million tons), and because acquisition-

release mechanisms most favourable to LDC interests would not shield

the farmer from the problem of enforced low ceilings on prices.

Food aid reforms

For developed countries, an approach more compatible with domestic

objectives may be to improve the responsiveness of food aid programmes

to the food security requirements of low-income countries with limited

foreign exchange reserves and fluctuating cereal import requirements.

This would require more explicit commitments to provide extra food aid

to cover exceptional import requirements of low-income countries,

backed up by unilateral reserves created as an adjunct of domestic farm

support programmes but restricted for release only to meet such food

security commitments.

Because of the chronic scarcity of foreign exchange and the lack of

control over domestic production and marketing systems in these low-

income countries, they are least able to take advantage of other food

security options offered by the international market. Consequently,

these countries need assurance that tonnages, financing, and transport

will be provided for extra cereal imports when production levels are low

or world prices are high. These countries normally devote less than 2% of

their annual foreign exchange earnings to commercial cereal imports, and

few could afford to increase this share in the face of larger import

%ost in this case equals the purchase requirements and/or higher world prices. Their only alternatives are to

price plus the interest payment on the IMF seek additional concessional assistance or accept the adverse conse-

credit during the first three years after

purchase, plus interest at market rates

quences for domestic consumption. Until domestic economic conditions

thereafter. improve, their food security needs can best be met through food aid

42 FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

commitments which will guarantee that unexpectedly large global

requirements arising from widespread production shortfalls can be met,

regardless of world market conditions.

One form of commitment which donors have so far failed to formalize

is the practice of supporting the World Food Programme’s International

Emergency Food Reserve at an annual level up to 500000 tons. This

reserve does not consist of a physical stock. Instead donors agree each

year on a level of contribution which they will make on a fast track in

response to emergency request channelled through the World Food

Programme. At present, the level of contribution is decided annually-

certainly there would be greater food security for potential recipients if

there were a multiyear commitment to a figure on the order of 500000

tons.

This amount should be sufficient to provide extra help to certain

countries with supply problems in normal years. However, it can scarcely

make a dent if there is a large-scale emergency. In years of widespread

production shortfall and low carry-over stocks, the amount of con-

cessional assistance required to meet food security needs could be sub-

stantially greater - some estimates place the figure as high as 12 to 16

million tons for developing countries as a whole.23 Donors could

theoretically commit themselves to increase food aid in times of world-

wide shortfall and high market prices on the strength of their own word,

but as a practical matter this would not be realistic unless they created

some kind of grain reserve to back up the commitment. Donors generally

implement food aid programmes by appropriating a fixed sum of money

each year for the purchase of commodities to be distributed as food aid. If

world prices are high, the appropriation will normally purchase less, not

more grain, and it is politically difficult to seek supplemental appro-

priations in a time of crisis.

Recognizing these constraints, the USA adopted legislation in 1978

creating a four-million ton wheat reserve to back up PL480 commitments.

This reserve assures that if grain prices are high and funds are tight, the

USA can nevertheless meet its minimum annual commitment of 4.5

million tons under the Food Aid Convention. The problem is that current

US assistance amounts to nearly 6 million tons. Thus a reserve which does

no more than back a minimum commitment will not provide true food

security in years when requirements are exceptionally large. This prob-

lem can be corrected by strengthening the food commitments under the

Food Aid Convention, and encouraging other donors to join the USA in

creating a network of unilateral reserves which will provide adequate and

explicit back-up for these strengthened commitments.

Article IV of the Food Aid Convention goes part way toward making

the necessary commitment. It provides that the governing body may

recommend that members increase the amount of aid available when

there are widespread shortages in developing countries. However, this

article will provide a true food security guarantee only if it is obligatory

rather than voluntary. As pointed out earlier, for exporters accumulating

stocks as a consequence of domestic farm programmes, the necessity of

holding them longer than is cost-effective may arise even if they are not

tied to food security commitments to LDCs. If food security benefit can

be obtained from a policy action which exporters will pursue in any case,

23Barbara Huddleston, ‘World food security it seems reasonable to suggest that steps be taken along these lines to

and alternatives to a new international

Wheat Agreement’, New lnterrtational ensure that this benefit is obtained. The current stock position in major

Realities, Vol6, No 2, March 1982. exporting countries, and the likelihood that unusually large amounts of

FOOD POLICY February 1983 43

The food security challenge

food aid will be required in some future years, makes this approach a

feasible option.

If there is movement in this direction, the proposal discussed earlier to

establish some sort of ‘food security assistance committee’ under inter-

national auspices becomes all the more important. The advantages which

would flow from creating a coordinating mechanism linking food aid and

aid for stock creation include the following:

0 Both forms of aid will be effective only when recipient countries are

pursuing food strategies which strike an optimum balance between

maximizing domestic production possibilities and maximizing

external trade opportunities; it is inefficient and sometimes counter-

productive for both donors and recipients to continue reviewing

these policies separately for each form of assistance.

0 Food aid can sometimes be used as an alternative to reserve stocks, at

other times as a source of supply for creating reserve stocks. In both

cases the effect of food aid and its availability must be explicitly

considered in formulating optimum procurement and stocks policies.

0 Conversely, the utility of food aid is affected by a country’s capacity

to manage its own internal marketing system. Where this manage-

ment capacity is deficient, a programme of assistance which offers

commodity aid as an adjunct to other assistance for storage and

marketing programmes can make both types of help more effective.

Under the auspices of such a committee, the respective roles of food aid

and of national stocks could be weighed and appropriate action taken in

response to both normal year-to-year harvest fluctuations and excep-

tional, widespread production shortfalls.

Conclusion

No single initiative adequately addresses the dual problem of stable

access to world food supplies at non-inflationary prices and a fair return

to efficient producers which constitute the joint concerns of LDC

importers and DC exporters in international food security. Given current

economic, commercial, and political conditions, the question for LDCs

remains how best to achieve an acceptable level of food security at

minimum cost. Too frequently LDC governments have pursued a line of

entrapment where the responsibility for resolving this dilemma rests with

the world’s principal producing countries. This position is neither entirely

appropriate nor productive. Rather, the present climate underscores the

need for political and economic readjustment that is both international

and unilateral in nature and rests on a number of fundamental pro-

positions:

0 Present international agricultural conditions and marketing systems

and institutions offer new means of achieving international food

security for developing countries in the next decade.

0 Concessional food resource transfers, if reconstituted under longer-

term commitments, differentiated policies responding to LDC eco-

nomic requirements, and tighter multilateral coordination, can be

beneficial to qualified aid-recipient countries.

0 The political climate in the context of existing economic conditions

does not augur well for elaborate new initiatives that require sub-

stantial additional expenditures among principal food donor

countries, unless their domestic interests are clearly well-served.

44 FOOD POLICY February 1983

The food security challenge

0 Surplus countries have tangible self-interests in contributing to more

equitable allocation of existing food resources and in promoting

market conditions where food security and price stability prevail over

the long-term.

0 Political and economic sophistication in the leadership and decision

making levels of developing countries enhances the prospects for

maximizing the benefits from current market conditions as well as

introducing those measures most appropriate to longer-term national

food security and self-reliance.

The derivatives of these propositions are the solutions themselves. For

developing countries they range from small measures such as introducing

efficiencies into procurement and marketing practices to large pro-

grammes focusing on domestic price policies and agricultural develop-

ment plans. For developed countries they include improvements in

operational rules for national stocks, clarification of objectives, and

improvement in the flow of assistance for both immediate consumption

needs and longer-term food security requirements for LDCs.

The necessary steps to achieve these solutions must be taken at both

national and international levels in a coordinated way. Neither unilateral

nor multilateral measures alone are sufficient. Acceptance of burden

sharing and mutual responsibility is the starting point. With a common

sense of purpose, it should be possible for the international community to

move forward in constructive ways to assure adequate and financially

accessible food supplies in world markets year after year, despite fluc-

tuating production conditions. Today’s apparent surpluses afford the

opportunity to renew that sense of purpose and respond creatively to the

continuing food security challenge.

FOOD POLICY February 1983 45

You might also like

- Watreatpath 3Document26 pagesWatreatpath 3bhaleshNo ratings yet

- Thiokaloid CallisiaDocument14 pagesThiokaloid Callisiadang bui khueNo ratings yet

- Watreatpath 3Document26 pagesWatreatpath 3bhaleshNo ratings yet

- GMP Sauces NebEntreDocument4 pagesGMP Sauces NebEntredang bui khueNo ratings yet

- Hướng dẫn Modd5Document316 pagesHướng dẫn Modd5Deadful MelodyNo ratings yet

- 1005 06RDocument6 pages1005 06Rdang bui khueNo ratings yet

- Michigan Department of Agriculture: Module 4 Table of ContentsDocument92 pagesMichigan Department of Agriculture: Module 4 Table of Contentsdang bui khueNo ratings yet

- Soy Protein Isolate and Protection Against Cancer: Original ResearchDocument4 pagesSoy Protein Isolate and Protection Against Cancer: Original Researchdang bui khueNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Final MarketingDocument47 pagesFinal MarketingRalp ManglicmotNo ratings yet

- Management AccountingDocument24 pagesManagement AccountingRajat ChauhanNo ratings yet

- American ExpressDocument1 pageAmerican ExpressErmec AtachikovNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Manab Gement 1 ModuleDocument75 pagesHuman Resource Manab Gement 1 ModuleNelly ChiyanzuNo ratings yet

- 2021 - 04 Russian Log Export Ban - VI International ConferenceDocument13 pages2021 - 04 Russian Log Export Ban - VI International ConferenceGlen OKellyNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary Note - Raghuram RajanDocument17 pagesParliamentary Note - Raghuram RajanThe Wire100% (22)

- Accounting Warren 23rd Edition Solutions ManualDocument47 pagesAccounting Warren 23rd Edition Solutions ManualKellyMorenootdnj100% (79)

- JOB CONTRACTING VS. LABOR-ONLY CONTRACTING GUIDELINESDocument7 pagesJOB CONTRACTING VS. LABOR-ONLY CONTRACTING GUIDELINESIscoDiazIINo ratings yet

- Agriculture in India - 1Document28 pagesAgriculture in India - 1utkarshNo ratings yet

- Value Creation OikuusDocument68 pagesValue Creation OikuusJefferson CuNo ratings yet

- Soal Ch. 15Document6 pagesSoal Ch. 15Kyle KuroNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument2 pagesEconomicsRian GaddiNo ratings yet

- Gr08 History Term2 Pack01 Practice PaperDocument10 pagesGr08 History Term2 Pack01 Practice PaperPhenny BopapeNo ratings yet

- Wells Fargo Combined Statement of AccountsDocument8 pagesWells Fargo Combined Statement of AccountsHdhsh CarshNo ratings yet

- Soneri Bank Ltd. Company Profile: Key PeoplesDocument4 pagesSoneri Bank Ltd. Company Profile: Key PeoplesAhmed ShazadNo ratings yet

- Capital Gains Taxes and Offshore Indirect TransfersDocument30 pagesCapital Gains Taxes and Offshore Indirect TransfersReagan SsebbaaleNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 (2) Sale Force ManagementDocument9 pagesAssignment 1 (2) Sale Force ManagementHira NadeemNo ratings yet

- ACF103 2014 – Week 2 Quiz Chapter 5 and 8Document6 pagesACF103 2014 – Week 2 Quiz Chapter 5 and 8Riri FahraniNo ratings yet

- Business Plan: Special Crammed Buchi Lot 4 Block 53, Katrina Uno Phase 1 Batinguel, Dumaguete City 09636084518Document16 pagesBusiness Plan: Special Crammed Buchi Lot 4 Block 53, Katrina Uno Phase 1 Batinguel, Dumaguete City 09636084518galelavNo ratings yet

- Assignment-UNIQLO Group-Marketing MaestroDocument57 pagesAssignment-UNIQLO Group-Marketing MaestroMonir KhanNo ratings yet

- Tahir 2020Document13 pagesTahir 2020Abu Jabbar Bin AmanullahNo ratings yet

- Online Course: Political and Market Framework: VietnamDocument32 pagesOnline Course: Political and Market Framework: VietnamTruong Dac HuyNo ratings yet

- Brand BlueprintDocument1 pageBrand BlueprintFirst Floor BD100% (1)

- Budgetary ControlDocument81 pagesBudgetary ControlRaghavendra Manuri100% (3)

- Fauji Cement Company LimitedDocument21 pagesFauji Cement Company LimitedMuneeza Akhtar Muneeza AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Debt, Preferred Stock, and Common Stock Long-Term Debt, Preferred Stock, and Common StockDocument22 pagesLong-Term Debt, Preferred Stock, and Common Stock Long-Term Debt, Preferred Stock, and Common StockRizqan AnshariNo ratings yet

- Virginia Henry BillieBMO Harris Bank StatementDocument4 pagesVirginia Henry BillieBMO Harris Bank StatementQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- KEY Level 2 QuestionsDocument5 pagesKEY Level 2 QuestionsDarelle Hannah MarquezNo ratings yet

- MBBsavings - 162674 016721 - 2022 09 30 PDFDocument3 pagesMBBsavings - 162674 016721 - 2022 09 30 PDFAdeela fazlinNo ratings yet

- Income Payee's Sworn Declaration of Gross Receipts - BIR Annex B-2Document1 pageIncome Payee's Sworn Declaration of Gross Receipts - BIR Annex B-2Records Section50% (2)