Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Progress On EU Sustainable Development Strategy

Uploaded by

Nicoleta CiobotaruOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Progress On EU Sustainable Development Strategy

Uploaded by

Nicoleta CiobotaruCopyright:

Available Formats

Progress on EU Sustainable

Development Strategy

Final Report

Client: European Commission, Secretariat General

ECORYS Nederland BV

Brussels/Rotterdam, 29 February 2008

Legal address:

ECORYS Nederland BV

P.O. Box 4175

3006 AD Rotterdam

Watermanweg 44

3067 GG Rotterdam

The Netherlands

Registration no. 24316726

Contact point:

ECORYS Brussels

Av. De Tervuren 13a

B-1040 Brussels

T +32 2 743 89 49

F +32 2 732 71 11

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 2

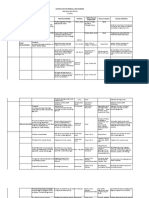

Table of contents

Executive Summary 5

Background and Aims 5

Main findings 6

Conclusions 13

Recommendations 16

1. Introduction 17

1.1 Background to the EU SDS 17

1.2 Aims of his report 18

1.3 How the report has been prepared 19

1.4 About the structure of this report 20

2. Climate change and clean energy 21

2.1 Introductory remarks on objectives and targets 21

2.2 Main challenges and problems facing the EU 23

2.3 Appropriate policy response and EU action 29

2.4 Member State action 37

2.5 Conclusions and recommendations 40

3. Sustainable transport 45

3.1 Main challenges 45

3.2 Views on the appropriate policy response 48

3.3 EU action 50

3.4 Member State action 52

3.5 Conclusions and recommendations 55

4. Sustainable consumption and production 58

4.1 Main challenges 60

4.2 Views on the appropriate policy response 63

4.3 EU action 65

4.4 Member State action 66

4.5 Conclusions and recommendations 68

5. Conservation and management of natural resources 71

5.1 Main challenges 71

5.2 Views on the appropriate policy response 74

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 3

5.3 EU action 75

5.4 Member State action 79

5.5 Conclusions and recommendations 82

6. Public health 85

6.1 Main challenges 85

6.2 Views on the appropriate policy response 87

6.3 EU action 89

6.4 Member State action 91

6.5 Conclusions and recommendations 94

7. Social inclusion, demography and migration 96

7.1 Main challenges 96

7.2 Views on the appropriate policy response 99

7.3 EU action 100

7.4 Member State action 102

7.5 Conclusions and recommendations 104

8. Global poverty and sustainable development challenges 106

8.1 Main challenges 107

8.2 Views on the appropriate policy response 110

8.3 EU action 110

8.4 Member State action 112

8.5 Conclusions and recommendations 114

9. Cross cutting policies 116

9.1 Education and training 116

9.2 Research and development 119

9.3 Financing and economic instruments 121

9.4 Communication, mobilising actors and multiplying success 123

9.5 Implementation, monitoring and follow-up 125

9.6 Conclusions 128

10. Conclusions and recommendations 130

10.1 Strategic conclusions 130

10.2 Progress by theme 133

10.3 Cross-cutting themes 135

10.4 Convergence of national SDS towards EU SDS 136

10.5 Monitoring 137

10.6 Recommendations 138

Annex 1: Overview of key policy initiatives by theme 139

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 4

Executive Summary

Background and Aims

i. On 9th June 2006, the European Council approved the new EU Sustainable

Development Strategy (EU SDS) 1. The main challenge of the current EU SDS is to

gradually change the current unsustainable consumption and production patterns

and the non-integrated approach to policy-making. The overall aim of the renewed

EU SDS is to identify and develop actions to enable the EU to achieve continuous

improvement of quality of life both for current and for future generations, through

the creation of sustainable communities able to manage and use resources

efficiently and to tap the ecological and social innovation potential of the economy,

ensuring prosperity, environmental protection and social cohesion. The themes are:

1. Climate change and clean energy;

2. Sustainable transport;

3. Sustainable consumption and production;

4. Conversation and management of natural resources;

5. Public health;

6. Social inclusion, demography, migration;

7. Global poverty and sustainable challenges.

The cross cutting policies are:

1. Education and training;

2. Research and development;

3. Financing and Economic Instruments;

4. Communication, mobilising actors and multiplying success.

ii. Implementation, monitoring and follow up. The EU SDS requires the Commission

to submit every two years (starting in September 2007) a progress report on

implementation of the EU SDS in the EU and the Member States (MS) also

including future priorities, orientations and actions. The Member States and DGs

have been asked to report to the Commission's Secretariat General (D2) on the

progress made. The Commission’s progress report consists of a political

Communication 2 and a detailed staff working paper 3 analysing progress in

quantitative and qualitative terms.

1

Council of European Union 15/16/th June 2006, see http://register.consilium.europa.eu/pdf/en/06/st10/st10917.en06.pdf

2

EC (2007) Progress Report on the European Union Sustainable Development Strategy 2007 (COM (2007) 642), see

http://ec.europa.eu/sustainable/docs/com_2007_642_en.pdf

3

EC (2007) Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the Progress Report on the European Union Sustainable

Development Strategy (SEC (2007)1416), see http://ec.europa.eu/sustainable/docs/sec_2007_1416_en.pdf

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 5

iii. The aim of this study is to assist the Commission in producing the Communication

and the staff working paper which will address two key questions:

• What progress has been made by the EU and Member States in implementing

the EU SDS?

• Is the EU on track compared to the objectives set within the key themes and

policies of the strategy?

This study is taken forward under the Framework Contract for Economic Analysis

of Environmental Policies and of Sustainable Development

(COWI/ECORYS/Cambridge Econometrics) and has been led by ECORYS

Netherlands/Brussels, in close-cooperation with COWI.

Main findings

iv. High importance is attached to climate change and clean energy; both the EU and

Member States give high importance to this theme and there is clear evidence that a

large number of diverse initiatives are being taken. Most attention is paid to

compliance with Kyoto, renewable energy, biofuels and energy efficiency targets.

However, much less attention is paid to post-2012 emission reductions, the

consistency of energy policy with competitiveness, security and broader

environmental targets. In addition, information is relatively scarce on adaptation to

climate change in other policies.

v. In the area of climate change and clean energy, there are a number of overlaps and

imperfections in the internal coherence within and between the individual

objectives/targets. In several cases, very different issues and levels of action are

included in one objective/target, making it a complex task to undertake a systematic

assessment of progress towards the objectives/targets in question. A further

problem is the lack of coherence between objectives/targets and actions. In a

logical framework approach, there should be a clear link between actions, outputs

and achievement of the objectives. This coherence is not clearly established, as

exemplified by adaptation to climate change, which has no corresponding actions

attached to it. For the purposes of the assessment in this report, we have analysed

each item included in the objectives/targets and actions of the SDS. On this basis,

we have subdivided three of the objectives/targets, and allocated the issues

addressed under the term "actions" in the EU SDS under each of the resulting

headings. A logical next step would be to assess whether these objectives should

be reformulated in a more coherent manner and whether all of them should be

maintained in the EU SDS.

vi. Most objectives and actions under the "climate change and clean energy" theme

result from separate processes in this field and are not directly driven by the EU

SDS. At the same time, the EU SDS process provides an opportunity to focus on a

range of sustainable development issues and their interrelationships in one process

and under one umbrella. This raises the question as to how the EU SDS can

contribute more to achieving the overall objectives in the area of climate change

and clean energy. One option would be to exploit the cross-cutting nature of the

sustainable development concept to focus activities under this theme on

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 6

mainstreaming energy and climate change issues into policies that may not be fully

aligned with the climate objectives. Examples of such policy areas include:

• Cohesion and structural funding;

• Trade policy;

• Agriculture, CAP;

• Research and technology development;

• Taxation, subsidies and other economic instruments;

• External relations broadly speaking, including policies relating to security,

development assistance and energy supply.

vii. In the area of sustainable transport, there is a focus on greenhouse gas emissions,

but only limited evidence of strategic thinking and overarching and well-founded

strategies. A range of key problems persist in the area of sustainable transport:

decoupling growth in demand for transport from economic growth and energy use

is one such problem. Ensuring that market prices reflect the real economic,

environmental and social costs of the different transport modes is another. Other

challenges include stimulating technological innovations and their adoption to

improve the performance of the road transport sector vis-à-vis emissions and

energy consumption; meeting the mobility needs of the urban population and of

groups with reduced mobility. Reconciling the growing demand for air transport in

Europe with environmental considerations is yet another challenge. Demand for air

transport is expected to double by 2020. The current capacity of the airport and air

traffic control infrastructure is inadequate for accommodating this demand.

Meeting future demand for air transport is also going to pose challenges with

regards to the safety of air transport 4.

viii. With regard to the progress reached by objective, there is only limited reason for

optimism in the area of sustainable transport. Decoupling is not happening: growth

of freight transport volumes has outpaced economic growth since 1995 and growth

of passenger freight transport has exceeded economic growth between 1990 and

2002. Growth in transport related energy use has exceeded growth in energy use in

all sectors: transport’s share of total energy consumption is increasing and oil

provides 98% of the energy used by the transport sector. Greenhouse gas

emissions from transport are increasing and it is doubtful whether the Kyoto targets

in this area can be met. The fleet average of 140g CO2/km by 2008 is unattainable

(in 2006 the fleet average was 162g CO2/km). Aviation and maritime sectors are

not covered by Kyoto and although harmful emissions are declining, air quality

problems in European cities persist. A shift to environmentally friendly transport

modes is not happening to date: road freight transport is still dominant and

continues to grow; passenger air transport has increased significantly; passenger car

transport shares have remained stubbornly stable and car occupancy rates and lorry

load factors are declining. There is still no comprehensive picture of the effects of

noise on health and quality of life. However, the situation is worrying since there is

strong evidence that noise contributes substantially to the loss of healthy life-years

and a large proportion of the population is exposed to noise pollution. Road

4

European Commission (2007) An action plan for airport capacity, safety and efficiency in Europe (COM(2006) 819), see

http://ec.europa.eu/transport/air_portal/airports/doc/2007_capacity_en.pdf

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 7

fatalities have been declining, but it is unlikely that the number of fatalities in 2010

will be half the number in 2000, especially in light of recent reports on the topic.

ix. It is recommended that the processes used for evaluating sustainable transport

projects need to be modified so as to enable consideration of non-infrastructure,

and when relevant, non-transport alternatives (for example tele-working).

Financing of transport projects with European and national funds should be made

contingent on meeting specified targets (for example, air quality, and noise

standards). The potential role of non-motorised transport in meeting mobility

needs is to be further investigated. Furthermore, the availability and quality of data

in the area of transport policy is unsatisfactory and needs to be remedied.

Currently, most transport policy decisions are based on modelling outcomes that

have not been sufficiently validated with real data. Targets in this area should in

future be binding. Additionally, urban transport should be given more attention and

prominence in any future sustainable transport strategy.

x. Although a wide range of actions is being initiated, there is only limited evidence in

the area of sustainable consumption and production (SCP) that countries are

scratching beyond the surface of this fundamental objective. Moreover, it is

doubtful whether the EU SDS has sufficient leverage in this domain to trigger

change. The international SCP concept is itself poorly defined. However, it is

clear that a focus on just one aspect of SCP is not sufficient to drive change in

consumption and production patterns. Furthermore, many current initiatives take

the form of action plans, programmes and policy reviews whereas it remains to be

demonstrated how well these can be translated into real action and progress on the

ground.

xi. The horizontal nature of SCP means that it affects all other themes within the EU

SDS. As such, the question arises whether including it in the strategy on equal

terms as the other themes actually furthers, or rather impedes, progress towards

SCP. We therefore recommend either making SCP a cross cutting issue, rather than

an independent theme, or better defining the concept and making several

clarifications. If SCP is maintained as an independent theme, it must be

demonstrated that so doing adds value. If this can be demonstrated, it is necessary

to:

• Provide a clear definition of the characteristics of this theme highlighting the

interrelationships with the other six themes of the strategy and communicate this

effectively to relevant stakeholders;

• The scope of the objectives must also be clearly defined e.g. objective 1 is

somewhat unclear as well as the resemblance of objectives 2a and objective 4;

• The objectives then need to be operationalised by introducing specific targets

and actions to be carried out, both regarding the Member States and the EU.

xii. Effective regulation on SCP needs to address both the consumption and production

level. Regarding consumption, conventional policy intervention plays a significant

role in creating an institutional framework for sustainable consumption securing

that prices reflect the environmental and social cost of a product or service.

However, consumption patterns are also determined by habits, traditions and

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 8

ethical considerations that are not easily influenced by legislative interventions.

Changing these patterns is a lengthy process that also requires non-conventional

initiatives. Here, the role of policy makers is to promote dialogue, and encourage

societal experimentation and learning processes.

xiii. Success is partial at best in the area of conservation and natural resource

management. Most progress has been made in halting biodiversity loss and

designating Natura 2000 areas. However, the key question about how to reconcile

economic growth with more sustainable patterns of economic development remains

unanswered. Europe still has high absolute and relative levels of material intensity

which is the main driver of resource extraction and use. A major and obvious

challenge is how resources should be used more efficiently, but also how to

monitor the effects of shifting natural resource extraction to non-EU states as the

EU is importing more of its requirements from abroad.

xiv. A variety of policy options is available to support better management and more

efficient use of natural resources. These commonly include economic measures

such as ecological fiscal reforms (e.g. material input and energy taxes), reforms of

the subsidy systems (e.g. temporary support for development of new eco-efficient

technologies and materials), certificates trading systems, and eco-efficient public

procurement. Focussing on key sectors that are either directly (e.g. mining,

agriculture, fisheries) or indirectly (e.g. energy, transport, and industry) responsible

for large amounts of natural resource extraction will benefit the efficiency of the

selected mix of instruments. Currently, Member States tend to neglect these issues

in their reports to a certain extent and put considerably more weight on biodiversity

strategies and biological conservation.

xv. It is recommended that the EU develops indicators to measure progress against

international objectives, which will help to place the EU's performance in an

international context. The work on sustainable development indicators by Eurostat

should be carried out in conjunction with other indicator work, including the

Lisbon structural indicators and the 6th Environmental Action Programme (6thEAP)

as well as UN-specific indicators on sustainable development. Despite progress in

nature reserve policies, there is no guarantee that current policies will be an

effective measure in the long term due to the dynamic nature of ecosystems and,

moreover, due to the increasing unpredictability of species’ habitat preferences

which may be altered by climate change. Furthermore, the indicators for the

objective of nature conservation may warrant re-examination and efforts should be

made to develop more sophisticated indicators for measuring biodiversity and

ecosystem well-being.

xvi. The information collected and used by Member States on public health is rather

good but still varies strongly. In this area, the EU is facing big challenges related

to the determinants of human health such as lifestyle, living and working

conditions, access to health services and the general socio-economic, cultural and

environmental conditions. This is mainly due to the ageing of populations and the

increase in lifestyle related diseases associated to obesity, physical inactivity, and

tobacco and alcohol consumption. There is also evidence that factors such as

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 9

particulate matter in the air, noise and ground-level ozone damage the health of

thousands of people every year. Other pollutants, including pesticides, endocrine

disruptors, dioxins and PCBs persist in the environment, accumulating over time

and we do not know enough about their long-term effect on health.

xvii. Strong support exists for the approach proposed by the European Commission in

this area, namely:

• Taking action where European added value is clear and where challenges are of

a cross-border nature;

• Integration of health considerations in all relevant policies;

• Ensure preparedness for health threats and protection of European citizens

through enhanced cooperation between the Member States;

• Promote the use of "life-cycle" and "key setting" approaches;

• Focus on health education to children in schools, information to adults in the

workplace and information to the elderly through targeted tools;

• Provide more support for health research and for geriatric medicines or under-

researched diseases and;

• Further develop the field of health technology assessment.

xviii. Several actions to promote good health on equal conditions and to improve

protection against health threats are undertaken or set up by Member States as well.

However, it is difficult to measure progress towards the EU SDS because:

• There is no baseline measurement available (except for some of the structural

indicators measured by Eurostat);

• No clear (process and outcome) indicators/targets are defined in the SDS on

public health;

• Some objectives are related to more than one health indicators (e.g. health

determinants: overweight persons, present smokers);

• Health consequences of several environmental hazards are not well understood

due to complex interactions;

• Evidence on (cost-)effective measures is not clear cut in all instances (e.g.

awareness campaigns).

xix. It is recommended to develop more quantitative outcome indicators to support

measurement of progress towards more general public health measures. A

monitoring system should be established to provide ongoing routine information to

demonstrate actual progress against goals. Cross–policy cooperation should be

increased, including through horizontal approaches and initiatives to mainstream

health into all policies. Furthermore, health impact assessment should be

institutionalised.

xx. Most countries provide reasonably comprehensive but rather fragmented reporting

in the area of social inclusion, demography and migration. The main challenge in

the area is to ensure and increase the quality of life, in light of the changing

demography – in particular the ageing population and increasing immigration.

Demographic change and the consequences for society have notably risen in

importance in the last few years. It is also understood to be a cross-cutting theme,

which has impacts on various aspects of economy and society. By now, it is

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 10

increasingly accepted that European societies will need to adapt to demographic

change – rather than resist it. Demographic change can also provide opportunities,

for instance in areas such as the 'silver economy'.

xxi. Although the social dimension of sustainable development is not even reported on

by some Member States (e.g. Denmark, Poland), most countries provide reasonably

comprehensive reporting in this area. The importance of demographic change,

social protection and immigration are increasingly recognised as themes that are

vital for Europe's future. Most attention goes to the reduction of poverty and active

labour market policies – promoting the inclusion of various target groups (older

workers, younger workers, migrants, women and the disabled); this is an important

objective not only from the point of EU SDS but also from the perspective of the

Lisbon Strategy and deserves full support from many perspectives (perhaps apart

from sustainable transport angle as it could lead to an increase in the number of

commuters). Indeed, active labour market policies – resulting in higher

participation rates – appear to be a key response to the demographic, social and

economic challenges ahead.

xxii. When restructuring the EU SDS in the area of social inclusion, demography and

migration, a stronger focus on a restricted number of objectives appear to be most

crucial for retention, namely:

1. Reduce the risk of poverty an social exclusion, focusing on child poverty;

2. Modernise social protection in view of demographic change;

3. Increase overall labour market participation (including females, younger, older,

disabled, migrants);

4. Develop an EU migration policy – including the need to strengthen

participation of migrants in social and economic life.

xxiii. The impression that emerges from the national reports is that the objective of

addressing global poverty and sustainable development is overstretched – and

often beyond the scope of individual Member States' influence. The fundamental

problem in the area of global poverty and sustainable development seems to be

twofold. Firstly, the scale and scope of the problem: the effects of global warming

on developing countries are of a scale beyond the intervention power of any single

nation and the longer term effects are very uncertain. A second key problem lies in

the tensions between developmental goals – taking into account the still expected

population growth, the related demand for resources and the environmental

concerns. The Millennium Goals themselves are largely contradictory; economic

development needed to alleviate poverty will lead to an increase in industrial

outputs, consumption of cereals and meat and above all mobility. Reconciling

these aims in an effective way is a vast challenge.

xxiv. Despite the overall commitment to actively promote sustainable development

worldwide and ensure that the EU's internal and external policies are consistent

with global sustainable development, the impression that emerges is that this

objective is far beyond the scope of individual Member States' possibilities. An

overall statement about the progress on this objective is, therefore, not possible.

Member States tend to focus on specific themes or geographic regions that are

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 11

particularly important to them – which may lead to a rather patchy approach and

not necessarily a good basis for monitoring overall progress in this area. A broad

support basis is, therefore, emerging amongst Member States for the establishment

of a UN Environmental Organisation. Within the light of expected and targeted

increases in Official Development Assistance, a stronger emphasis on the

effectiveness and efficiency of such aid would have been expected (Paris

Declaration). Those Member States that are currently building up their external

development aid strategies have a unique opportunity to include the SD dimension

immediately – yet there is little sign that this is actually happening.

xxv. Beyond the horizon lie new and complex challenges – the social and environmental

impact of the demand for bio-fuels, the increased demand for commodities from

emerging markets and their interrelations. In light of these challenges, it is

recommended to focus the objectives of the EU SDS in this area and to distinguish

between wider objectives (beyond the reach of the EU as a whole) and specific

objectives (referring to EU objectives).

xxvi. Reporting on the cross-cutting themes is rather problematic; by formally giving the

cross cutting themes the same rank as the seven key challenges, the EU SDS of

June 2006 makes clear that it attaches equal importance to them. However, the

strategy does not provide a clear frame of reference against which progress on the

cross-cutting themes could be measured. In this respect, the EU SDS it is open to a

certain degree of interpretation what exactly is to be achieved under each heading

and what measures are to be taken. The fact that, in contrast to the seven key

challenges, there is no subdivision into operational objectives and targets on the

one, and actions on the other side, adds to that.

xxvii. Education and training is among the cross-cutting themes that have received

considerable attention in the progress reports, and Austria, France and Sweden are

good examples. However, the dominant stream of reporting shows (too) strong a

focus on school education and neglect of adult- and continuing education, as well

as vocational education and training. In many reports, the role education and

training are to play in the concept of SD is merely confined to teaching about the

environment and the importance of its preservation. This approach does not

sufficiently acknowledge the breadth of the SD concept.

xxviii.The EU SDS defines the role of research and development in sustainable

development in a broad way. However, this approach only found entry in less than

half of the MS progress reports. While virtually all MS assign great importance to

research and development in the field of renewable energy, energy saving, as well

as transport technology, the wider context of SD receives insufficient attention.

This narrow focus on supporting research into new technologies does not do justice

to the concept of SD and this section should not be confined to the creation and

availability of technology and knowledge, but also include scientific research

concerning its usage and uptake. A meaningful interlinkage of natural and social

sciences to further the cause of SD is only pursued by few MS, for instance in

Germany.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 12

xxix. As concerns the usage of finance and economic instruments to promote SD, nearly

all Member States report an increase or the introduction of taxes related to energy

consumption or pollution. However, information on the usage of extra income

levied by these taxes is patchy and only a handful of states report an actual shift in

taxation from labour to resource and energy usage, as called for in the Strategy.

Finland is one of these few exceptions.

xxx. Only few MS seem to have a coherent strategy in place that would answer the

question as to what role communication and public involvement is to play in SD.

As a consequence, most MS report on a range of rather limited and seemingly

unrelated communication campaigns that address certain elements of SD and not

the concept as a whole. A clear rationale how communication and the involvement

of various groups of actors can contribute to progress in the SD area is almost

entirely missing. Overall, few MS really seem to have the ambition to enhance

public perception of SD issues on a broad scale.

xxxi. Clearly, the challenge for Member States to implement and report on SDS progress

is substantial. It requires good interministerial cooperation and horizontal methods

of working; the ability to synthesise all outputs varies considerably between

Member States.

Conclusions

1. The EU SDS remains relevant as the key European framework for promoting

sustainable development; sustainable development is becoming increasingly

important in European, national, regional and local policy making. The EU SDS

from June 2006 serves as a useful starting point for promoting sustainable

development in Europe. As such, its ambitions are high, particularly as it aims to

be coherent and broad-based, and addressing the fundamental behaviour of citizens

and firms is far from easy.

2. The EU SDS represents a prioritisation at a specific point in time. Various

sustainable development challenges are competing with each other. The 7 themes

can be considered equal in importance, but in practice the themes 1 and 2 may well

be considered as more important than themes 6 and 7. As of late, the theme of

climate change is clearly racing to the top, while sustainable consumption and

production and public health are also increasing in importance. Other priorities –

such as conservation and natural resource management or sustainable transport –

remain equally vital but there tend to be less key policy initiatives.

3. It is early day to review progress. At the time progress reports were submitted by

Member States, the EU SDS had been adopted just one year earlier. In light of the

need to translate the EU SDS to national practices, this can be considered a short or

even very short time frame for measuring progress.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 13

4. The contexts for Member States is different – there is no one size fits all. The

ability to contribute to themes varies strongly; some Member States are not

willing/able to report on some themes at all – and this is sometimes indeed due to

the context. New Member States often face particular challenges, e.g. in areas of

energy conservation and pollution control. However, there is often more scope for

progress in the New Member States. For example, meeting the Kyoto targets in

this part of Europe is eased in the light of the closure of polluting factories.

5. EU and National SD are not the same; a fair amount of countries (about 1/3) prefer

to use structures that deviate from the EU SDS – often relying on the priorities as

set under National SD strategies. This is understandable in the light of the fact that

the alignment of these national strategies to the EU SDS will take time.

6. Signals of success can be recorded in all areas, but progress is overall encouraging

in areas of product lifecycle thinking and minimising waste; increasing the share of

national territory that receives protected status for the benefit of nature

conservation; sustainable forestry initiatives, harder targets for various

environmental policy areas such as energy efficiency, climate change, organic

farming, and active labour market policies. Key initiatives are also taken to curb

lifestyle related diseases, pandemic preparedness, and to improve the handling of

chemicals, while Official Development Assistance is increasing in order to live up

to Millennium Objectives more globally.

7. Reporting on various themes falls short and Member States can be reluctant to look

back. Conservation and natural resource management notably is a theme where

reporting is rather weak – there is only limited or no reporting on areas where

progress is limited or where actions are non-existent. Even when taking into

account the various national contexts, some Member States did not to report on

specific themes at all which leads to considerable white spaces. An example is the

objective to address the impact of globalisation on workers – where only two

countries (France and Finland) record initiatives.

8. Certain areas of relevance to SD are not explicitly covered; e.g. spatial planning/

land use/urban development or addressing wastelands (New Member States)

receive only limited attention. Despite reference to Local Agenda 21 and referring

to local and regional actors, the spatial or urban dimension could provide powerful

solutions, e.g. in the area of decoupling economic growth from transport demand.

9. Reporting is not always focused on key policy initiatives. A general tendency is to

report extensively on the situation without coupling this to specific policy

initiatives. Another tendency in the reports is to focus on future goals and targets

rather than on key policy initiatives that have been taken recently.

10. The relation between key policy initiatives and their impact is not direct – a time

lag is present. Therefore, it may be too early to measure the impact of the EU SDS

at this stage. Furthermore, a link between initiatives and impacts can be established

much more directly in some areas (e.g. public health) then in some other areas (e.g.

climate change), where relations are much more indirect. Furthermore, impacts can

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 14

vary between geographic levels: what is sustainable at one level may not be

sustainable at another level.

11. The added value of the EU SDS compared to National SDS cannot be measured

yet. The EU SDS priorities have impacted the majority of national SD strategies;

however a fair number still focuses on national priorities. The impression arises

that many national SD policy initiatives would have been taken without an EU SDS

as well.

12. The relation between the EU SDS and the Structural Funds is controversial. In the

12 New Member States, vast investment programmes in infrastructure are on their

way. In Poland for instance, the Operational Programme for Infrastructure

represents an EU investment of € 27 billion for the period 2007-2013 – of which a

considerable part will be invested in roads. The impact on SD is uncertain – at

least. However, on a more positive note, Structural Funds are also used for

investing in environmental infrastructures, such as waste water treatment plans,

while the Operational Programmes on Human Resources appear to be well aligned

with the EU SDS objective on social inclusion, demography and migration.

13. Impacting mainstream policies is the real challenge for the SDS. A real value

added of the EU SDS could be that it takes environmental (and social, economic)

priorities out of a silo and into the mainstream of national policy making. The

extent to which national and EU strategies are successful in this varies. For

instance, the EU SDS thus provides an excellent opportunity to analyse and

promote the integration of climate change and energy objectives in the policy areas

that may not already be fully aligned with the climate objectives. Examples of such

important policy areas include:

a. Cohesion and structural funding;

b. Trade policy;

c. Agriculture, CAP;

d. Research and technology development;

e. Taxation, subsidies and other economic instruments;

f. External relations broadly speaking, including policies relating to security,

development assistance and energy supply.

14. International literature on SDS informs us about the complexity of challenges.

Also reports are being launched in which unwanted side-effects of key policy

initiatives are mentioned. Such complexities are rarely reported about in the

Member State reports; interlinkages between and within themes are not always

sufficiently grasped and much reporting can said to be fragmented.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 15

Recommendations

a. Need to establish a hierarchy of objectives; sustainable transport could well be

regarded as an intermediate objective and there is a need to structure and prioritise

these objectives much better. The number of objectives is currently very large,

especially when the cross-cutting themes are seen to have similar weight. This risk

of overstretching reduces the possible impact of the EU SDS; a streamlining of the

EU SDS is, therefore, needed from a logical perspective.

b. Internal cohesion within themes needs to be strengthened. Operational

objectives/targets often demonstrate overlap; a hierarchy between operational

objectives – sometimes logical – appears to be missing; this leads to a less than

optimal coherence. The inconsistencies within themes make reporting by Member

States as well as the assessment of MS reporting more difficult and are likely to

have contributed to gaps in MS reporting.

c. Increase the impact of the EU SDS on mainstream policies through impact

assessments. The cross-cutting nature of sustainable development provides a

valuable opportunity to address the mainstreaming of the various SD themes in EU

and national policies. More of the focus in EU SDS implementation could be

directed toward assessing and promoting integration of sustainable development

priorities in main strands of EU and MS policy such as agricultural policy,

structural and cohesion funds, and trade policy.

d. Strengthen links with the Lisbon Strategy, especially in areas where synergy exists.

For instance actions to promote labour market participation or the promotion of

environmental technologies are in line with both concepts and there would be

significant scope for strengthening these links and join forces.

e. Promote SD specifically in New Member States; national policies are often still

under development or review in the New MS and considerable investment

programmes are being taken forward; more inclusion of SD thinking and acting

could lead to significant impacts at the EU level. This is especially important in

the light of major EU-funded investment programmes that will help to modernise

the economic infrastructure – an opportunity to test these programmes and projects

against sustainable development objectives.

f. At the latest by 2011, the European Council will decide when a comprehensive

review of the EU SDS needs to be launched. Already now, we can see

considerable scope for strengthening the EU SDS in such a way that it could make

more impact and contribute more effectively to the ever increasing number of

sustainable development challenges.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 16

1. Introduction

1.1 Background to the EU SDS

Sustainable development means that the needs of the present generation should be met

without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It is an

overarching objective of the European Union set out in the Treaty, governing all the

Union’s policies and activities. It is about safeguarding the earth's capacity to support life

in all its diversity and is based on the principles of democracy, gender equality, solidarity,

the rule of law and respect for fundamental rights, including freedom and equal

opportunities for all. It aims at the continuous improvement of the quality of life and

well-being on Earth for present and future generations. To that end it promotes a

dynamic economy with full employment and a high level of education, health protection,

social and territorial cohesion and environmental protection in a peaceful and secure

world, respecting cultural diversity 5.

In 2001, the European Council in Göteborg adopted the first EU Sustainable

Development Strategy. This was complemented by an external dimension in 2002 by the

European Council in Barcelona in view of the World Summit on Sustainable

Development in Johannesburg (2002).

On 9th June 2006, the European Council approved the new EU Sustainable Development

Strategy (EU SDS) 6. The main challenge of the current EU SDS is to gradually change

the current unsustainable consumption and production patterns and the non-integrated

approach to policy-making. The overall aim of the renewed EU SDS is to identify and

develop actions to enable the EU to achieve continuous improvement of quality of life

both for current and for future generations, through the creation of sustainable

communities able to manage and use resources efficiently and to tap the ecological and

social innovation potential of the economy, ensuring prosperity, environmental protection

and social cohesion. The themes are:

1. Climate change and clean energy;

2. Sustainable transport;

3. Sustainable consumption and production;

4. Conversation and management of natural resources;

5. Public health;

6. Social inclusion, demography, migration;

7. Global poverty and sustainable challenges.

5

Council of European Union 16/17th June 2005, see http://ue.eu.int/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/ec/85349.pdf

6

Council of European Union 15/16th June 2006, see http://register.consilium.europa.eu/pdf/en/06/st10/st10917.en06.pdf

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 17

The cross cutting policies are:

1. Education and training;

2. Research and development;

3. Financing and Economic Instruments;

4. Communication, mobilising actors and multiplying success;

5. Implementation, monitoring and follow up.

The EU SDS requires the Commission to submit every two years (starting in September

2007) a progress report on implementation of the EU SDS in the EU and the Member

States also including future priorities, orientations and actions. The Member States and

DGs have been asked to report to the Commission's Secretariat General (D2) on the

progress made. The Commission’s Progress report consists of a political

Communication 7 and a detailed staff working paper 8 analysing progress in quantitative

and qualitative terms.

1.2 Aims of his report

This study is taken forward under the Framework Contract for Economic Analysis of

Environmental Policies and of Sustainable Development (COWI/ECORYS/Cambridge

Econometrics) and has been led by ECORYS Netherlands/Brussels, in close-cooperation

with COWI.

The aim of this study is to assist the Commission in producing the Communication and

the staff working paper which will address two key questions:

• What progress has been made by the EU and Member States in implementing the EU

SDS?

• Is the EU on track compared to the objectives set within the key themes and policies

of the strategy?

In each of the thematic areas, the study will therefore aim to address the following

questions:

a. What are the key challenges facing the EU in this area and what are their relations?

b. Is there a clear view from the professional/academic community on the appropriate

policy response?

c. What are the latest developments in EU action to tackle the challenge/problem and

how to assess these in an international context?

d. What are the latest developments in MS action to tackle the challenge/problem and

how can these be assessed?

This report concerns primarily the assessment of national Member State reports that were

submitted to the Commission in the period June-August 2007 and addresses primarily the

question d. above. This assessment is framed within the broader context of independent

7

EC (2007) Progress Report on the European Union Sustainable Development Strategy 2007 (COM (2007) 642), see

http://ec.europa.eu/sustainable/docs/com_2007_642_en.pdf

8

EC (2007) Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the Progress Report on the European Union Sustainable

Development Strategy (SEC (2007)1416), see http://ec.europa.eu/sustainable/docs/sec_2007_1416_en.pdf

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 18

literature and draws on the expertise of thematic experts in each of the fields concerned.

The study is complementary to the Progress Report prepared by Eurostat and the

Commission’s own analysis.

1.3 How the report has been prepared

The report has been prepared in close co-operation with the Commission services, in

order to make it as useful as possible as an input to the overall progress review.

The following steps have been executed:

1. Overall analysis of the EU SDS, including its internal and external coherence – we

have assessed the coherence of the EU SDS from a logical perspective by using a

problem and objective tree, and gathered general literature of relevance to the EU

SDS;

2. Preparation of thematic fiches – in each of the seven thematic areas, assigned

experts have prepared thematic fiches based on EU sources, the national progress

reports available and independent sources that are referred to in this report;

3. Organisation of a thematic workshop – all thematic experts participated in a

thematic workshop held in Brussels on 15th August 2007, where an overview of key

problems and key responses was discussed by theme, followed by a broader

assessment of overall progress and generation of interim conclusions. Templates for

the preparation of thematic chapters and tables were then developed and agreed;

4. Drafting of thematic chapters and tables - based on standardised templates and

taking into account the latest information from Member States, thematic experts then

prepared the basis for the assessment as well as detailed tables where national

progress by country and objective have been recorded.

5. Complementary analysis of cross-cutting SDS themes – subsequently the cross-

cutting themes have been analysed on the basis of the national progress reports

mostly;

6. Compilation of the interim report – an interim report prepared in September 2007

focused on the assessment of the national progress reports and was used as input to

the Commission’s own progress report;

7. Compilation of draft final and final reports – the current report presents the key

findings of the study including the conclusions and recommendations.

Despite the comprehensive nature of this report, it is often limited by the information

provided by Member States. Another limitation of this progress report is the brief period

between the launch of the EU SDS (June 2006) and the cut-off date for the national

progress reports (June 2007). In view of this short time span, the report focuses on recent

key policy initiatives (mid 2006 until August 2007), rather than on context indicators or

measured progress on the ground. Other elements that hamper the measurement of

progress towards the EU SDS:

• There is usually no baseline measurement available (except for some of the structural

indicators measured by Eurostat);

• Although there is an increasing amount of sustainable development indicators being

used, these are not always fully in line with the EU SDS themes. There is also a lack

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 19

of sophisticated indicators for measuring progress towards many themes and

objectives;

• No clear indicators and targets are defined in the EU SDS with regard to several

themes and objectives;

• Some objectives are unclear as to their linkages with others, i.e. how halving road

transport deaths by 2010 fits the objective to reduce levels of transport energy use;

• Evidence on effective measures is not always clear from either the academic or

policy literature. For example, does investing in costly waste treatment plants

generate better value-for-money than tackling waste generation at source?

1.4 About the structure of this report

This report is structured as follows. Chapters 2 to 8 will assess the progress in each of the

seven thematic areas: climate change and clean energy; sustainable transport; sustainable

consumption and production; conservation and management of natural resources; public

health; social inclusion, demography and migration; and global poverty and sustainable

development challenges. Each of the chapters presents the main challenges in the area,

views on the appropriate policy response, EU action, Member state action and ends with

conclusions and recommendations.

Chapter 9 gives an overview of the progress in cross-cutting policies, namely: education

and training; research and development; financing and economic instruments;

communication, mobilising actors and multiplying success; and governance of the

strategy.

Chapter 10 draws conclusions and devises recommendations. It summarises progress by

theme, the structure of the strategy, the monitoring of the SDS, the convergence of

national and EU SDS, cross-cutting themes and recommendations.

Annexes 1-8 comprise the overview of key policy initiatives by theme, objective and

country.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 20

2. Climate change and clean energy

Overall Objective from the EU SDS: To limit climate change and its costs and negative effects to society

and the environment

• Objective 1: Kyoto Protocol commitments of the EU-15 and most EU-25 to targets for reducing

greenhouse gas emissions by 2008 – 2012, whereby the EU-15 target is for an 8% reduction in

emissions compared to 1990 levels. Aiming for a global surface average temperature not to rise by

more than 2ºC compared to the pre-industrial level.

• Objective 2: Energy policy should be consistent with the objectives of security of supply,

competitiveness and environmental sustainability, in the spirit of the Energy Policy for Europe

launched in March 2006 by the European Council. Energy policy is crucial when tackling the

challenge of climate change.

• Objective 3: Adaptation to, and mitigation of, climate change should be integrated in all relevant

European policies.

• Objective 4: By 2010 12% of energy consumption, on average, and 21% of electricity consumption, as

a common but differentiated target, should be met by renewable sources, considering raising their

share to 15% by 2015.

• Objective 5: By 2010 5.75% of transport fuel should consist of biofuels, as an indicative target,

(Directive 2003/30/EC), considering raising their proportion to 8% by 2015.

• Objective 6: Reaching an overall saving of 9% of final energy consumption over 9 years until 2017 as

indicated by the Energy End-use Efficiency and Energy Services Directive.

Only few areas can claim that they have risen to the top of the policy agenda in such a

short time. In just one year time, climate change and clean energy have become a key

concern at both international, European, national, regional and local level. In this chapter

we will take stock of the progress that has been made in this area, which figures so

prominently in the EU SDS.

2.1 Introductory remarks on objectives and targets

A closer look at the "objectives and targets" of the EU SDS shows that there are a number

of overlaps and some imperfections in the internal coherence both within and between the

individual objectives/targets. In several cases, very different issues and levels of action

are included in one objective/target, making it a complex task to systematically assess

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 21

progress towards the objectives/targets. Furthermore, not all objectives/targets have

corresponding actions attached to them 9.

For the purposes of the assessment in this report, we have analytically considered each

individual item included in the objectives/targets as well as the actions of the SDS. As a

result of this process, we have subdivided three of the objectives/targets, while at the

same time trying to accommodate the issues addressed under the term "actions" in the EU

SDS under each of the resulting headings.

The following objectives/targets have thus been applied to the assessment of EU and

national progress in implementing the EU SDS:

Objective/target 1a Comply with Kyoto Commitments (through domestic measures,

EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) and Joint Implementation

(JI) / Clean Development Mechanism (CDM))

Objective/target 1b Medium- and long-term EU emission reductions (post-2012)

consistent with 2ºC (including review and extension of EU ETS)

Objective/target 1c Work toward an international framework post-2012 consistent

with 2ºC (reduction pathways by the group of developed

countries in the order of 15-30% by 2020 and beyond)

Objective/target 2a Energy policy consistent with competitiveness

Objective/target 2b Energy policy consistent with security of supply

Objective/target 2c Energy policy consistent with environmental sustainability (incl.

non-climate environmental impacts of energy)

Objective/target 3.a Mitigation integrated in all relevant (EU) policies (including e.g.

forestry, agriculture, cars, aviation, carbon capture and

sequestration, taxation)

Objective/target 3.b Adaptation integrated in all relevant (EU) policies.

Objective/target 4 Renewable Energy (including biomass). Targets for Renewable

Energy (12%) and Renewable Electricity (21%). Analysis of

long-term promotion of Renewable Energy Sources (RES),

consider new targets. Long-term strategy for bio-energy beyond

2010.

Objective/target 5 Promotion of Biofuels. 5.75% of transport fuel by 2010. Analysis

of long-term promotion of biofuels

Objective/target 6 Energy efficiency in demand and supply. (Save 9% in

consumption until 2017. Adopt Action Plan bearing in mind the

EU energy saving potential of 20% by 2020. Promoting the use of

combined heat and power.)

9

The question of internal coherence among the objectives and actions within the EU SDS and a possible reorganisation of the

objective tree is dealt with further in Section 1.5.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 22

2.2 Main challenges and problems facing the EU

a. A range of emerging challenges facing the EU

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has published three volumes of

its Fourth Assessment Report (AR4). The Working Group 1 (WG1) report reinforces the

significance of man-made emissions to global climate change. The Working Group 2

(WG2) report confirms evidence that many natural systems are being affected by regional

climate changes, particularly temperature increases. The Working Group 3 (WG3) report

analyses mitigation options for the main sectors, including long-term mitigation strategies

for various stabilisation levels. These and many other studies confirm the major overall

climate-related challenges facing the EU:

• To make significant emission reductions in the near term and move onto a path of

very significant emission reductions in the period to 2050, global emissions of

greenhouse gases will need to peak in the next 10 to 15 years and then be reduced to

very low levels, well below half of levels in 2000 by mid-century, if concentrations

are to be stabilised at safe levels.

• To address adaptation to unavoidable climate change that will happen even in a

scenario limiting global climate change to the EU 2 degree target.

The recent Vienna conference under the United Nations Framework Convention on

Climate Change (UNFCCC) also confirmed that avoiding the most catastrophic forecasts

made by the IPCC would entail emission reductions in the range of 25-40% below 1990

levels by industrialised countries by 2020 10.

Aggregate projections from the European Environment Agency (EEA) show that the

EU15 is barely on track to meet its Kyoto commitments of 8% reduction by 2008-12.

The 2010 emissions of the EU15 are only expected to be 0.6 % below base-year levels

(i.e. a 7.4 % distance from the emission reduction commitment). Additional domestic

measures are projected to reduce the gap by a further 4.0 %, down to 3.4 % by 2010.

Kyoto mechanisms are expected to deliver an additional 2.6 % emission reductions and

the removal through sinks should provide the remaining 0.8 %. The developments

confirm that decoupling of energy consumption and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions

from economic growth remains a major challenge.

With the approval of an Action Plan on an integrated energy and climate change package

by the March 2007 European Council 11, the EU has decided on a number of challenging

targets in relation to climate and energy policy :

• Emission reductions of 20/30% by 2020

• 20% Renewable Energy (RE) by 2020

• 10% biofuels by 2020

• A review of the EU Emission Trading Scheme

10

See:

http://unfccc.int/files/press/news_room/press_releases_and_advisories/application/pdf/20070831_vienna_closing_press_relea

se.pdf

11

Council of the European Union 8/9th March 2007, see

http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/ec/93135.pdf

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 23

A major challenge now remains in terms of agreeing on the burden sharing among the EU

27 countries when it comes to meeting the targets. In doing so, a large number of

national circumstances, interests and concerns as well as diverse policy regimes (e.g. with

regard to support schemes for deployment of Renewable Energy Technology (RET)) need

to meet under an umbrella covering all of the major elements of the climate/energy

package.

Ensuring that the significant increase in the use of biomass and biofuels is realised in a

sustainable way without compromising environmental and other sustainable development

concerns within the EU and in developing countries will be an important challenge.

While mitigation of climate change remains a major priority and challenge, adaptation to

the unavoidable climatic change that is already taking place now, in order to limit its

adverse effects on economies and natural systems is bound to take on a more prominent

position in the future. In the past, national initiatives in relation to adaptation have

dominated, but with its recent Green Paper on adaptation 12, the Commission is

increasingly devoting attention to this field.

A major challenge facing the EU are further negotiations on a global and comprehensive

post-2012 agreement building on the Kyoto Protocol. It is the EU's ambition that

negotiations should be completed by 2009. This takes place in a challenging context

where both the USA and developing economies, whose participation is vital to reach the

necessary emission reductions, remain reluctant to accept binding quantitative

commitments.

In a situation where impacts of climate change and the urgency of mitigation becomes

increasingly evident, mainstreaming of climate change concerns in broader foreign policy

is likely to be called for.

Security of supply is increasingly a concern which guides EU energy policies with import

dependency set to rise steadily over the coming decades.

Rising and volatile oil and gas prices are seen as a major challenge and a potential threat

to the economic development and competitiveness of Europe.

Research and development of sustainable energy technologies addresses exposure to

supply and price risks for fossil fuels while at the same time constituting an important

platform for European exports of climate-friendly technologies. In the longer term,

technology development is an essential factor in making possible the steep cuts in

emissions that will become necessary.

12

EC (2007) Green Paper "Adapting to climate change in Europe – options for EU action" (SEC (2007)849), see http://eur-

lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/com/2007/com2007_0354en01.pdf

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 24

The findings of Eurostat's "Measuring progress towards a more sustainable Europe

2007" 13 confirm this picture, stating that the evaluation of changes in the Climate Change

and Energy theme shows that there are no favourable changes to report compared to

2000. Key findings include the following:

• Following the considerable progress achieved in reducing greenhouse gas emissions

during the 1990s, and despite a significant reduction between 2004 and 2005, the

EU-15 trend has reversed and is now moving away from the target. In 2005, EU-15

emissions of greenhouse gases stood at 98% of their Kyoto base year value, while

EU-27 emissions were at 92.1% of their 1990 value. Overall greenhouse gas

emissions grew by 1.5 percentage points (EU-27) and 1.4 points (EU-15) between

2000 and 2005. Since 2000, the EU-15 emissions trend has thus been moving away

from the Kyoto target path.

• Gross inland energy consumption continues to grow. Since 2000, gross inland

energy consumption has grown at 1.1% per year for both EU-27 and EU-15,

growing considerable faster in EU-27 than in the previous decade, and reflecting

increasing energy demand. The switching from high-carbon solid fuels towards gas

and renewables continues, but at a slower pace. The greenhouse gas intensity of

energy consumption is thus moving in the right direction, but progress is too slow to

make a major contribution.

• The rate of energy dependency continues steadily to increase. EU-27 dependence on

imported energy has increased every year since 2000, and in 2004 exceeded 50%,

ending up 5.7 percentage points higher in 2005 than in 2000. The energy

dependency of EU-15 is about 3 percentage points higher than that of EU-27.

• The share of renewables in primary energy consumption is increasing, although at a

rate so slow that the distance from the target path is widening each year. The EU-27

consumption of renewable energy sources increased at the significant average rate of

4.1% between 2000 and 2005. Nevertheless, due to the relatively high growth rate

of energy consumption over recent years, the share of renewables has increased by

only 0.17 percentage points per year since 2000, reaching a level of 6.6% in 2005,

far from the 2010 target of 12%.

• Little, if any, progress has been made in increasing the share of renewables in

electricity consumption. Progress in the share of renewables in electricity

consumption has slowed down since 2000, growing at an average of 0.04 percentage

points per year compared with 0.14 during the previous decade. This leaves a gap of

7 percentage points between the level of 14% in 2005 and the 2010 target of 21%.

Achieving the target will require growth of 1.4 percentage points per year,

equivalent to the entire progress made between 1990 and 2000.

• The production of electricity through combined heat and power also appears to be

making little progress towards the 2010 target of 18%, standing at only 10.5% in

2004.

• Despite the growing use of biofuels in transport, the level of uptake in 2005 was

1.1%, far below the target level of 2% set for that year.

13

Eurostat (2007) "Measuring progress towards a more sustainable Europe – Sustainable development indicators for the

European Union", see

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page?_pageid=1073,46587259&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL&p_product_code=K

S-77-07-115

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 25

• Emissions due to international bunkers, which are not covered by the Kyoto

Protocol, account for a small but rapidly growing proportion of greenhouse gas

emissions, equivalent to 5.6% of the total in 2005 in EU-27, compared with 6.6% for

EU-15. Their share has increased significantly since 1990, from 1.2% to 2.4% for

aviation and from 1.9% to 3.1% for shipping.

b. Key problems and their interconnections

Objective/target 1a: Comply with Kyoto Commitments

Several EU15 countries are facing difficulties in bringing emissions pathways in line with

Kyoto targets. Many have been forced to introduce strong additional measures to limit

emissions, and the first period of EU ETS did not contribute strongly to emission

reductions. However, EU-15 countries are expected to comply with the commitments,

and most of EU12 have little problems in this regard due to steep emission reductions

since the base year 1990.

Objective/target 1b: Medium- and long-term EU emission reductions (post-2012)

consistent with 2ºC

Current energy and transport policies would mean EU CO2 emissions would increase by

around 5% by 2030. This is clearly not sustainable in view of the need for developed

country GHG emissions to be reduced by at least 20-30% (as per the decision of the

European Council) or even 25-40% by 2020 (a figure around which there is growing

consensus, cf. the recent Vienna meeting of the UNFCCC).

Objective/target 1c: Work toward an international framework post-2012 consistent with

2ºC

Keeping the long-term objective of 2ºC within reach will require global greenhouse gas

emissions to peak within 10-20 years, followed by substantial reductions perhaps by as

much as 50% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. Developed country emissions would

have to decrease by as much as 80-95% to keep CO2eq concentrations at compatible

levels. Such drastic emission reductions will require that a strong international

framework is established for the period after 2012.

Objective/target 2a: Energy policy consistent with competitiveness

Energy price volatility and price rises are issues already affecting EU economies today,

and could do so even more in the future with continuing growth in global demand

combined with continued concentration of supply reserves.

Objective/target 2b: Energy policy consistent with security of supply

Europe is becoming increasingly dependent on imported energy. Without measures to

address this situation, the EU's energy import dependence for gas is expected to increase

from 57% to 84% by 2030, and for oil from 82% to 93%.

Objective/target 2c: Energy policy consistent with environmental sustainability

The energy sector emits other air pollutants in addition to CO2. Nitrogen oxides (NOx),

particulate matter (PM) and sulphur dioxide (SO2). Emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O) and

methane (CH4) from agriculture and other sectors contribute to air pollution as well.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 26

With existing air pollution legislation, the health effects would mean a loss of life

expectancy of around 5.5 months, and ground-level ozone would be causing some 21,000

premature deaths in the EU by 2020 at a cost ranging from € 162bn to € 587bn.

Objective/target 3a: Mitigation integrated in all relevant (EU) policies

Mainstreaming climate and energy policies in all relevant policies and sectors is a major

challenge. The EU ETS provides a powerful instrument for influencing developments

and emissions pathways in the sectors covered. Policies and measures in several other

sectors are also important from a climate perspective. These include agriculture, land-

use, waste, and industrial GHGs. The most difficult sector to handle from an emission

mitigation perspective has been the transport sector with continuously growing emissions

from road, marine and air transport. Integration of short, medium, and long term climate

and energy concerns is also a challenge in cross-cutting policy areas such as Research and

Technological Development (RTD) and cohesion policy. Also trade policy, international

development cooperation and other aspects of general foreign policy have been identified

as increasingly relevant policy areas to include in a comprehensive approach to climate

change 14.

Objective/target 3b: Adaptation integrated in all relevant (EU) policies.

All countries will need to take measures to adapt to climate change in order to lessen the

adverse impacts of global warming on people, the economy and the environment.

As explained in the Green Paper on adaptation, Northern countries are already

experiencing higher rainfall while those in the South struggle to cope with more frequent

droughts. Up to half of Europe’s plant species could face extinction by 2080. Economic

actors in climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and tourism will

be directly impacted, and so will infrastructure in transport, public utilities and power

production.

Integration of adaptation in development cooperation is receiving increasing attention

because developing countries are relatively more exposed to the bulk of climate change

impacts and have least adaptive capacity to deal with it. Furthermore, adaptation plays an

important part in the international climate negotiations. A recent assessment by the

OECD of the experience with integrating adaptation into development cooperation 15

concluded that while there is increasing awareness and high-level policy endorsement

within donor agencies for the need to integrate adaptation, more efforts are needed with

regard to:

• Assessing the implications of climate change on development co-operation activities

• Development of operational measures on integrating adaptation considerations

within development activities.

• Cross-fertilisation and collaboration between agencies and institutions.

14

Foreign Policy and Climate Change - An exploration of options for greater integration. IISD for Danish Ministry of Foreign

Affairs (2007).

15

OECD (2007), Stocktaking of Progress on Integrating Adaptation to Climate Change into Development Co-operation Activities

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 27

Objective/target 4: Renewable Energy

In 1997, the European Union established a target of a 12% share of renewable energy in

the energy mix by 2010. Although renewable energy production has increased, the share

of renewable energy is unlikely to exceed 10% by 2010, and only a limited number of

Member States have made serious progress in this area.

The lack of a coherent and effective policy framework throughout the EU and long-term

targets are seen as contributing factors 16. For example, wind is not sufficiently harnessed

in many countries due to delays in authorisations, unfair grid conditions and slow

reinforcement and extensions of the electric power grid 17.

Objective/target 5: Promotion of Biofuels.

Biofuels are today the only direct substitute for oil in transport that is available on a

significant scale, thereby potentially providing improved security of supply and, if

produced in a sustainable way, GHG emission reductions from the constantly growing

transport sector. By 2005, biofuels were in use in most Member States with a market

share of 1%, which is less than the non-binding target stipulated in the biofuels directive.

However, there are three main categories of concerns raised in relation to biofuel

production:

1) That they may be produced in ways that do not deliver significant greenhouse gas

savings;

2) That they may be produced in ways that cause significant environmental damage, for

example to biodiversity;

3) That the demand for biofuels may drive up food prices to the detriment of poor,

food-importing countries.

Several important contributions by international organisations have flagged these

concerns, such as the above-mentioned joint contribution from the United Nations 18 to the

public consultation on biofuels. Similar conclusions were drawn in the OECD-FAO

Agricultural Outlook 2007-2016 report, which finds that growing biofuel demand is

likely to keep food prices high and rising throughout at least the next decade. A new

report for the OECD Round Table on Sustainable Development 19 concludes that:

• The rush to energy crops threatens to cause food shortages and damage to

biodiversity with limited benefits;

• Second-generation technologies hold promise but depend on technological

breakthroughs;

• The economic outlook for biofuels seems fragile;

• Government policies supporting and protecting domestic production of biofuels are

inefficient and not cost effective;

• Liberalising trade in biofuels is difficult but essential for global objectives;

16

Energy Policy for Europe

17

Report on progress in renewable electricity – COM (2006) 849. 2) Identification of administrative and grid barriers to the

promotion of electricity from Renewable Energy Sources (RES-E), see

http://ec.europa.eu/energy/res/consultation/doc/2007_07_06_grid_barriers/progress_analysis_2007_07_admin_barriers_en.pdf

18

http://ec.europa.eu/energy/res/consultation/doc/2007_06_04_biofuels/non_og/un_en.pdf

19

Biofuels: is the cure worse than the disease?, Paris, 11-12 September 2007.

Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy 28

• Certification of biofuels is useful for promoting good practices but cannot be trusted

as a safeguard;

• Current biofuel support policies place a significant bet on a single technology

despite the existence of a wide variety of different fuels and power trains that may

be options for the future.