Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Name of The Company Retention Strategy Impact

Uploaded by

Kalpana SharmaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Name of The Company Retention Strategy Impact

Uploaded by

Kalpana SharmaCopyright:

Available Formats

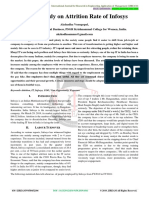

Figure 4

Examples of Retention Strategies for young

Professionals in India’s BPO and Services

Sectors

Name of the

Retention Strategy Impact

Company

A choice of working in

over 170 offices across

40 countries in a variety Significant

Tata

of areas. impact on job

Consulting

Paternity leave for hopping

Services(TCS) adoption of a girl child achieved

Discounts on group

parties

Identification of

Have been

potential talented staff

able to

ICICI Bank Alternative stock

achieve higher

options

retention rate

Quicker promotion

WIPRO ‘Wings Within’ Has led to a

programme where higher

existing employees get a retention rate

chance to quit their

current job role and join

a different firm within

Figure 4

Examples of Retention Strategies for young

Professionals in India’s BPO and Services

Sectors

Name of the

Retention Strategy Impact

Company

WIPRO

Fostering a sense of

belongingness, creative

artistic and social

Moderate

activities for the

Retentions

INFOSYS employees and their

rate increase

families.

achieved

Initiating one of the best

‘corporate universities’

in the world

Microsoft- Excellent sporting and Struggling to

India wellness facilities minimise job

Employees allowed to hopping

choose flexible working

schedule

Moving people across

functions and sections in

assisting employees find

Figure 4

Examples of Retention Strategies for young

Professionals in India’s BPO and Services

Sectors

Name of the

Retention Strategy Impact

Company

their area of interest

Culture change valuing

innovation and talent

over age and experience

Institutionalising a Stabilised job

Mahindra &

practice called ‘reverse hopping

Co mentoring’ where young significantly

people are given

opportunities of

mentoring their seniors

India remains handicapped by enormous infrastructure

and institutional .

(labour and capital) constraints. The question is not

whether India has not begun

to produce an impressive record in growth, employment,

and poverty reduction,

but rather how to overcome the obstacles impeding even

faster progress, as the

global economic system becomes increasingly

competitive.

According to the Report of the 2nd National

Commission on Labour, the perceived benefits of

globalization are as follows:

Sustained economic growth, as measured by gross

national product is the

path to human progress.

Free markets, with little or no intervention from

government, generally

result in the most efficient and socially optimal allocation of

resources.

Economic globalization, achieved by removing barriers

to the free flow of

goods and money anywhere in the world, spins

competition, increases

economic efficiency, creates jobs, lowers consumer

prices, increases

economic growth and is generally beneficial to everyone.

Privatization, which shifts functions and assets from

government to the

private sector, improves efficiency.

The primary responsibility of the government is to

provide the

infrastructure necessary to advance commerce and

enforce rule of law

with respect to property rights and contracts.

However, there is a growing realization that globalization

is not an

unmixed blessing. It can at best be an outcome, not a

prerequisite for successful

growth strategy.

Advent of libralisation, privatization and globalisation

Policies of privatization and disinvestment are being

pursued as part of

economic reforms in India. The objectives of disinvestment

basically are:

To enhance budgetary receipts.

To minimize budgetary support towards loss making

units.

To improve performance by bringing out changes in

ownership and

performance

To ensure long term viability and sustainable levels of

employment

in public sector enterprises.

Broad based dispersal of shares, especially in the profit-

making

public sector enterprises among investors (Venkata

Ratnam &

Naidu 2002, p. 19).

The following are among the several

demerits or pitfalls of globalization:

The process of globalization seems to be driven by a

few in a uni-polar

world whereby it is benefiting few and hurting many.

It is another form of imperialism.

It is leading to growing inequalities between the rich

and the poor, both at

the level of individuals and among countries.

It is destroying jobs and local communities.

It is ruthless, root less, jobless, fruitless…(UNDP,

1996).

Whatever form it takes, social effects

of privatization or restructuring will

be as follows :

Initial overstaffing will lead to rationalization,

retrenchment and

displacement of labour

Informalisation of the economy

Stagnation of employment in organized sector

Growing casualization of labour .

In dealing with the redundant workers, several options are

available

though not all are equally attractive in solving the problem

of unemployment.

These are : 7

Voluntary retirement scheme (VRS)

Cash compensation or golden handshake

Retraining of workers

Redeployment

Counselling

Eventual Rehabilitation

Creation of unemployment benefit and social security.

New Actors and the Emerging Dynamics.

The industrial relations system

comprises certain actors in a certain context. The actors

are a hierarchy of managers or of workers and trade

unions. Then, there are governmental agencies. In the

post-liberalization, globalization era, consumers and

community have begun to assert themselves and take a

significant role. When the rights of consumers and

community are affected, the rights of workers/unions

and managers/employers are taking a back seat.

The court rulings are borne by the realization that wider

public good matters most in preference to the narrow self

interest of a minority. Workers and unions, in particular are

asked to assert their rights without impinging on the

rights of others, particularly the consumers and the

community. Hence, the ban against bandhs and even

restrictions even on protests and dharnas.

Increasingly, trade unions are getting isolated and see a

future for themselves and their members only when they

align themselves with the interests of the wider society.

As regards the changes in the industrial relations

machinery, it is felt that inspection of establishments

cannot be done away with. However, the process

of inspection can be used to create awareness and to

educate the employers and workers with regard to benefits

of timely and genuine compliance. The role of inspector

can also be modified so that he acts as a facilitator helping

employers in complying with the provisions of the laws.

Selective and purposeful inspections have to replace

routine statistics oriented inspections. Similarly, the

conciliation officers need to be well aware of the new

challenges posed by globalization before the employers

and employees and equip themselves with necessary

knowledge, attitude and skills to handle industrial disputes

whose nature and dimensions will be very different from

industrial disputes hitherto handled.

To be successful, they have to avoid 5 ‘A’s and promote 3

‘H’s:

A1 ….. Anger H1 ….. Honesty

A2 ….. Anxiety H2 ..... Health

A3 ….. Annoyance H3 ….. Helpfulness

A4 ….. Arrogance

A5 ….. Arguments

The process of globalisation has forced trade unions to be

defensive and

maintain a low profile. Therefore, there is a need for the

industrial relations machinery to be more proactive and

vigilant so that undercurrents of discontentment and

grievances are detected in time as unions may not report

the grievance in changed environment.

Labour Market Flexibility

Even within the organized sector, an increasing number of

jobs are approximating the character of these in the

unorganized sector as a result of the increasing labour

market flexibility in the wake of globalization. A

comprehensive survey of about 1300 firms scattered over

10 States and nine important manufacturing industry

groups, shows that between 1991 and 1998, employment

increased at the rate 2.84 per cent per annum

(Deshpande et al, 2004). Nonmanual employment

increased at 5 per cent per annum whereas manual

employment increased at 2.29 per cent. This increase is in

total employment was brought by increasing the share of

non-permanent employees and increase in manual

employment by increasing the share of women workers.

Smaller firms grew faster than bigger firms. Firms, which

increased sales, increased manual employment as did

those which employed contract workers.

Employers who increased fixed capital per worker reduced

manual employment.

Employers increased employment but only of one or other

category of nonregular flexible workers.

It was found that as a whole over the 7 years of

liberalization (between 1991 and 1998) dualism in the

labour market did increase. The share of permanent

manual workers declined from close to 68 per cent in 1991

to 64 percent in 1998. Not only did the share of non-

permanent increase but the share of casual in non-

permanent increased even faster. It is the big firms that

resorted to the greater use of non-permanent workers.

Holding all other factors constant, firms employing 50-99

workers and those employing 500 or more workers,

increased the share of non-permanent workers

significantly between 1991 and

1998. Also, firms employing 500 workers or more

increased the share of

temporary workers.

Industrial Disputes Act: Mr. Yashwant Sinha, the then

Finance Minister

in his budget speech (2001) stated that the chapter VB

would be amended to

raise the existing limit from 100 workers to 1000 workers.

The Chapter V-B of

the I.D. Act regulates lay off, retrenchment and closure in

an industrial

establishment which engages more than 100 workmen,

and which is not of a

seasonal character. All factories, mines and plantations

are covered under this

chapter. This resulted in criticism from several trade union

quarters. The

severest criticism emanated from the founder President of

BMS.

The Task Force on Employment Opportunities (Ahluwalia

Committee)

recommended doing away completely with the permission

clause in all

establishments. The threshold limit of 100 was introduced

by the 1976

amendment to the ID Act. Prior to that, the limit was 300 or

more workers. The

Second National Labour Commission has recognized the

need for providing

flexibility to the employers in handling labour to promote

competitiveness and

improve productivity in the context of globalization. The

Commission has taken

care to provide a safety net cushion to the workers.

The Commission believes if the employer could decide the

size of the

employment at the start of the business, why should he

not do so during the

conduct of the business. Therefore, it has recommended

the repeal of section

9A which relates to issue of notice of change in the

conditions of work.

The Commission has also favoured complete freedom to

the employers to

lay off or retrench workers. Further, it has recommended

restoration of the

original threshold limit of 300 or more workers relating to

the need of the

employers to get prior permission from the appropriate

Government for closure.

However, the Commission has suggested payment of all

dues to the workers and

higher compensation to the workers than provided in the

I.D. Act.

Just as an industrialist has a right to establishing a factory

or start a

mining or plantation operation, equity demands that he

should have freedom to

close down the establishment. In the era of globalization

and severe competition

in the manufacturing, mining and plantation sectors

(commodity sector), it is

necessary to have an urgent re-look into the provisions of

the Industrial Disputes

Act relating to lay off, retrenchment and closure. In several

advanced countries,

there is a clear-cut hire and fire policy. Even in China there

are not many

restrictions in this regard. Time has come to review the

provisions in the I.D. Act

relating to this subject. A simpler hire and fire policy can

attract more FDI in the

manufacturing, plantation and mining sector.

The two clauses which are considered out of tune in a

globalised scenario

cover the following aspects:-

(a) Rationalisation, standardization or improvement of

plant or

technique which is likely to lead to retrenchment of

workmen;

(b) Any increase or reduction (other than casual) in the

number of

persons employed or to be employed in any occupation or

process

or department or shift (not occasioned by circumstances

over which

the employer has no control)

As globalization has resulted in increased competition, the

manufacturing

industry was adversely affected resulting in diminishing

rate of growth in this

sector. The sector could not face the competition given by

the Chinese goods

flooding the market at affordable prices. It is reported that

the rate of growth of

manufacturing sector of China is almost twice that of India.

This certainly calls for

introspection. The time has come to deal with these two

clauses of Fourth

Schedule appended to the I.D. Act as rationalization,

technological upgradation

and improved productivity are of an imminent necessity.

Impact on Industrial Relations including in the newly

emerging Services

Sector

Most of the trade unions have opposed the policy of

globalization,

economic reforms, privatization and disinvestments. They

attempted to

demonstrate unity in such opposition and organized

nation-wide strikes and

bandhs. The marked feature of post globalization is that

the unions in the private

sector hesitate to go on strike. The public sector

undertakings viz. Coal India,

Singareni Collieries Ltd., Indian Airlines, Air India, ports

and docks, banking and

insurance sector, telecom, power sector continued to be

plagued by industrial

unrest.

After the great railway strike of 1974 which paralysed the

railways

functioning throughout India for nearly a month, it has

been generally quiet on the

railway front. The well established Permanent Negotiating

Machinery is

functioning more or less smoothly. Hence, there have

been only a few local

instances of unrest since the opening up of the economy.

Similarly, after the

historic strike of textile workers in Maharashtra in 1982

which resulted in loss of

employment of more than 75,000 workers, the textile

workers are generally

hesitant to go on strike, barring a few exceptions viz. the

prolonged strike of Delhi

textile workers in 1986.

Workers of Coal India Ltd. have participated in several

agitational

programmes even after the advent of globalization. It

appears there is no impact

of globalization on the trade unions operating in Singareni

Collieries Company

Ltd. The workmen of public sector airlines industry have

gone on sporadic

strikes from time to time even after the opening up of the

economy.

The trade unions operating on ports and docks have

agitated on several

occasions on the issue of Productivity Linked Bonus. They

have demanded this

bonus on all ports basis which is not a rational one. The

staff of public sector

banks have been opposing privatization and have also

been agitating for revision

of their salary. The staff had to concede for all-round

computerization and also

21

flexible deployment policy. The insurance sector workers

have been agitating for

revision of their salary from time to time.

Power sector reforms have resulted in unbundling and

privatization of

power sector companies resulting in acceleration of

agitational programmes by

the unions. Despite the disturbances in the public sector,

the telecom industry is

rapidly moving towards 250 million customers with the

highly versatile phones

and tariffs matched with the world class technology. The

Indian telecom industry

is moving forward in a revolutionary mode. The private

sector has not been

affected by any visible industrial relation problems.

) Liberalization, globalization and IR

The above situation reflects the "normal" pattern of labour

market activities governing employment

relationships in industrialized and industrializing countries until

recently. But a number of

destabilizing influences have now emerged, and have coalesced

around the forces of liberalization

and globalization.

(i) Overview

The move towards market orientation (liberalization) in many

countries has been reflected in

deregulatory policies by governments, including the reduction

of tariff barriers, facilitating the flows

of capital and investment, and privatization of State owned

enterprises. Liberalization has preceded

or been forced by globalization (involving greater integration in

world markets, and increased

international economic interdependence). Both phenomena

have been facilitated by the significant

growth in world trade and foreign direct investment in recent

years, and by information technology

which has facilitated rapid financial transactions and changes in

production and service locations

around the world.

Recent data (1991-93) indicates that about two thirds of the

inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI)

is to advanced industrialised countries, which are also the

source of some 95% of the outflows of

such investment (UNCTAD 1994:12) . The most significant

sources of FDI are multinational

corporations (MNC's) based in the US, Japan, UK, Germany and

France.

During the period 1981-92, FDI valued at $US203 million flowed

to the ten largest developing and

newly industrialising countries (This represented 72% of the

total FDI to such countries). The ten

countries or territories concerned were (from highest to

lowest): China, Singapore, Mexico,

Malaysia, Brazil, Hong Kong, Argentina, Thailand, Egypt and

Taiwan [China] (UNCTAD 1994:14).

The proportion of East Asian countries in this group is notable,

as is the growing significance of

Singapore, Taiwan [China] and Korean MNC's as investors in

China and other Asian developing

countries. In this regard, between 1986-92, about 70% of FDI

flows into China, Indonesia, the

Philippines and Thailand, originated in other Asian countries,

with about 18% coming from Japan

and 50% from Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan [China] and Korea

(ILO/JIL 1996: page 3, note 2).

The flow of FDI within the region can be expected to increase

with the further development of the

trading areas constituted by the Association of South East Asian

Nations (ASEAN) and Asia-Pacific

Economic Cooperation (APEC).

(ii) The relevance of globalization to IR - a summary

Increasing international economic interdependence has

disturbed traditional IR arrangements in

several broad ways.

Firstly, such arrangements have normally been confined to the

circumstances created by national

markets; but globalization has fundamentally changed, and

considerably expanded, the boundaries of

the market place. In this respect, the extent of information

flows made possible by new technology is

building inter-enterprise networks around the world, is calling

into question the traditional

boundaries of the enterprise and is eroding current IR

arrangements.

MNC's are the primary driving force for change. They are

organizations that engage in FDI and own

or control productive assets in more than one country (Frenkel

and Royal 1996a:7). They are creating

very complex international production networks which

distinguish globalization from the simpler

6

forms of international business integration in earlier periods. As

producers of global goods and

services (notably, in the area of mass communications), centres

of networks and large employers,

MNC's have an impact extending far beyond urban centres in

the countries in which they are located.

In addition to the activities of MNC's, many locally-based

enterprises, of varying sizes, in many

countries are using information technology to focus on the

demands of international (and domestic)

"niche" markets in a way which is contributing to a growing

individualization and decollectivism of

work.

Secondly, globalization has disturbed the status quo between

"capital" and "labour" in each country,

in the sense that capital is significantly more mobile in an open

international environment, while

labour remains relatively immobile (here it should be noted

that, under globalization, international

labour migration is continuing, but, proportionately to the rate

in the1970's, has not increased - see

World Bank 1995: 53). This can place "labour" at a relative

disadvantage, in that "capital" can now

employ "labour" in different countries, at lower cost and on a

basis which can prejudice the

continuing employment of workers in the originating country.

Thirdly, globalization is having a contradictory impact on IR. It is

accelerating economic

interdependence between countries on an intra- and inter-

regional basis and encouraging similarities

in approach by individual enterprises in competitive markets.

This may lead to some convergence in

industrial relations arrangements around the world. At the

same time, there is clear evidence of

resistance towards convergence, based on particular national

and regional circumstances (eg, in

Europe and Asia). This aspect will be considered later in the

paper, in relation to Asia and the

Pacific.

(iii) The role of MNC's

The principal focus of the changes taking place in response to

globalization is at the level of the

individual (predominantly, private sector) enterprise. MNC's

have had and will continue to have a

key role in these changes (see below), although this role should

not be overestimated (Kuruvilla

1997:5-6). UNCTAD estimates that, globally, there are about

37,000 MNC's having over 206,000

affiliates. Over 90% of MNC's are based in advanced countries,

with nearly half of all affiliates in

newly industrializing and developing countries (UNCTAD 1994:

3-5).

MNC's are a major employer of labour. Globally, approximately

73 million persons are employed by

these enterprises. This constitutes nearly 10% of paid

employees engaged in non-agricultural

activities worldwide, and about 20% in developed countries

alone (UNCTAD 1994: xxii - xxiii).

Compared with the position in parent enterprises, there has

been a substantial increase in

employment in MNC foreign affiliates, particularly in developing

countries, during the 1990's. The

World Bank estimates that MNC's employ in the order of 12

million workers in developing

countries, but affect the livelihood of probably twice that

number (World Bank 1995: 62).

What is the impact of MNC's in local markets, particularly

where they are competing for workers?

And what is their relationship with trade unions? Available

evidence suggests that larger MNC's

generally pay more than local firms and at least match or

exceed working conditions and other

employment benefits in the local labour market (UNCTAD

1994:198-201). While there are still

disturbing incidences of "fly by night" MNC's, an increasing

number of MNC's are emphasising their

social responsibility, which reflects itself in a basic commitment

to workers' welfare and "guiding"

the employment practices of subcontractors and joint venture

partners (UNCTAD 1994:325-27).

This role is being reinforced through promotion of the ILO's

7

Tripartite Declaration and the OECD Guidelines concerning

Multinational Enterprises, and, more

recently, through industry codes of conduct on labour practices

in various countries. MNC

relationships with trade unions are influenced both by labour-

management relations in their country

of origin and circumstances in their host country. In general, it

seems that MNC's prefer not to

recognise trade unions or to bargain with them; but normally

do so where it is required (eg, by

legislation). Where MNC's appear to be predisposed towards

trade unions, it is usually towards

unions based in the enterprise. Overall, MNC's vary

considerably in their IR/HRM strategies, and

this an important area for future research in Asia and the

Pacific.

(iv) Information technology and IR

The impact of changes in information technology on the

organization of production and work at

enterprise level - the IR heartland - provides a specific example

of the forces encouraging and

supporting globalization. The discussion which follows reflects

the situation - currently or

developing - in many western industrialized countries, and in

the more advanced Asian countries. It

is a trend which is likely to spread more generally across the

Asia and Pacific region with increasing

industrialization and the impact of globalization.

Increased competition in global (and in many domestic)

markets has created demand for more

specialised, better quality items. This has lead to higher

volatility in product markets and shorter

product life cycles. These circumstances require enterprises to

respond flexibly and quickly to

changes in market demand.

In terms of the organization of production, new technologies

are increasing the scope for greater

flexibilty in production processes, and are resolving

information/coordination difficulties which

previously limited the capacity for production by enterprises at

different locations around the world.

Where enterprises are servicing more specialised markets,

smaller and more limited production

processes are now involved. New technology has also made it

possible to produce the same level of

output with fewer workers. In both situations, there is

increased emphasis on workers having higher

value capacities and skills to perform a variety of jobs. This has

blurred the distinctions (both

functional and hierarchical) between different kinds of jobs and

between labour and management

generally. In addition, efforts to improve products (through

innovation, quality, availability and

pricing) have led enterprises to establish cross-functional

development teams, transcending

traditional boundaries between engineering, manufacturing

and marketing. These developments have

been accompanied by the erosion of the standardized,

segmented, stable production process (of the

"Ford" type) which had facilitated collective IR. In many

industries and enterprises there are also

fewer workers available to be organized in trade unions.

Another area of enterprise activity to be affected by

globalization concerns the organization of work.

To achieve the flexibility and productive efficiency required to

respond quickly and effectively to

market changes, narrow worker job descriptions are having to

be re-written. This is resulting in work

tasks based on broader groupings of activities, emphasising the

undertaking of "whole" tasks. In the

interests of greater efficiency, work is also being re-organized,

giving greater emphasis to teambased

activities, and re-integrated with a view to improving linkages

across units and departments

within an enterprise.

Related changes have seen a "flattening" of management

hierarchies and devolution of greater

operational responsibility and authority to lower level

managers, supervisors and work teams. In this

process of adaptation, many enterprises have been increasingly

relying on internal and external

8

"benchmarking" to establish and maintain "best practice", and

to emphasise "organisational learning"

(ie, applying lessons related to superior performance to the

work of individual managers and

workers). All of these changes are directed to achieving

stronger commitment by workers to the

enterprise and its objectives and closer relations between

managers and workers, based on

consultation and cooperation.

Finally, enterprises have been seeking to "rationalise" their

operations to strengthen further their

competitiveness, by reducing costs (including both wage and

non-wage labour costs). Responses

have included identifying core functions (ie, those which define

its essential rationale and

competitive edge and must be maintained), and subcontracting

(or reconfiguring existing such

arrangements) for the performance of peripheral functions

outside the enterprise; substituting

technology for labour; and "downsizing". Strategic alliances and

company mergers have also

increased markedly during the past decade. This has made the

employment environment for workers

in the formal sector in many industrialized, and increasingly in

industrializing, countries much more

unstable.

(v) The impact of other trends

To these developments must be added other changes which

have been taking place to the IR

environment in many countries, and as a result of broader

societal changes. The impact and the pace

of these changes has varied from country to country, and will

have varying impact in the Asia and

Pacific region. They include the continuing shift in employment

from manufacturing to serviceoriented

industries, accompanied by a shift from traditional manual

occupations to various forms of

"white-collar" employment. Also, public sector employment (in

both line Ministries and state-owned

enterprises) continues to decline in most countries.

Broad social developments in many countries have also

witnessed the increasing incidence of women

in the labour force. This has been combined with growing

demand for atypical forms of employment

(eg, part-time, temporary and casualemployment; and home

work, in the form of certain kinds of

process work and, increasingly, telework).

All of these changes have affected IR, and are likely to continue,

to a greater or lesser extent, in

individual countries. The manufacturing and public sectors in

many countries have been the

traditional base of support for trade unions. They are now

experiencing considerable difficulties in

maintaining and increasing membership, as the source of

growth in many economies is increasingly

coming from a services sector whose workers (many of whom

are women) have demonstrated a

reluctance to join unions.

(d) The changing nature of IR - a re-definition?

As noted previously, IR is not a self-contained area of activity. It

can only be understood clearly by

reference to the persons, groups, institutions and broader

structures with which it interrelates

(including, for example, changing product markets, the

processes of labour market regulation, and

the education and training system) within a particular country,

as well as to influences arising from

beyond its borders.

The development of global enterprises, the changes occurring

in the course of industrialization and

the impact of new management systems (particularly, HRM)

require a broader perspective to be

taken on employment relationships.

9

The scope of IR must now be viewed as extending to all aspects

of work-related activities which are

the subject of interaction between managers, workers and their

representatives, including those which

concern enterprise performance. But issues which are critical to

the manner in which an enterprise

operates - such as job design, work organization, skills

development, employment flexibility and job

security, the range of issues emerging around HRM, and cross-

cultural management issues - have not

until recently been considered as part of labour-management

relations; and, in many cases, they have

not previously been made the subject of collective bargaining

or labour-management consultation.

But this situation is changing, and has been particularly

noticeable in Western industrialized

countries.

A broader approach to IR would seek to harmonize IR and HRM,

by expanding the boundaries of

both fields.In particular, IR will need to address, much more

than it does currently, workplace

relations - and people-centred - issues, and recognise that it

can no longer focus only on collective

relations. Given the range of issues which should now be the

subject of labour-management

exchange at enterprise level, it may be that a different, more all

embracing expression (for example,

"employment relations") might be used to describe these

relations.

You might also like

- Building Manufacturing Competitiveness: The TOC WayFrom EverandBuilding Manufacturing Competitiveness: The TOC WayRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Employee Retention Challenges in BPO Industry An Empirical Study ofDocument10 pagesEmployee Retention Challenges in BPO Industry An Empirical Study ofKristine BaldovizoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Attrition in BpoDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Attrition in Bpoc5pgcqzv100% (1)

- Imagineering The Future of HR OrganisationDocument28 pagesImagineering The Future of HR OrganisationVrushieNo ratings yet

- Infosys Case StudyDocument4 pagesInfosys Case StudyJerold Savio50% (2)

- Retention Strategies With Reference To BPO SectorDocument4 pagesRetention Strategies With Reference To BPO Sectoru2marNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions 14619Document4 pagesMergers and Acquisitions 14619Latha KNo ratings yet

- HRM Related Issues To BpoDocument40 pagesHRM Related Issues To BpoHardeep NebhaniNo ratings yet

- Employee Engagement Strategies With Special Focus On Indian FirmsDocument18 pagesEmployee Engagement Strategies With Special Focus On Indian FirmsAbinash PandaNo ratings yet

- Skill Development: The Key to Economic ProsperityDocument5 pagesSkill Development: The Key to Economic ProsperitySadhi KumarNo ratings yet

- Final Mcom ProjectDocument47 pagesFinal Mcom ProjectGautamChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Employee EngagementDocument40 pagesEmployee EngagementsofiajoyNo ratings yet

- Attritiontrendsin IndiaDocument19 pagesAttritiontrendsin IndiavijendraNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis PDFDocument87 pagesFinal Thesis PDFAnonymous oSq4OFdNo ratings yet

- Chapter-I: Recruitment and Selection Process of Insurance CompaniesDocument96 pagesChapter-I: Recruitment and Selection Process of Insurance Companiesnasho_sonu15No ratings yet

- Attrition Trends in IndiaDocument19 pagesAttrition Trends in IndiaSeema0% (1)

- 2003 Apr Jun 075 082Document8 pages2003 Apr Jun 075 082Rahim MardhaniNo ratings yet

- HRD Emergence in India and its Wide-Ranging ScopeDocument6 pagesHRD Emergence in India and its Wide-Ranging ScopeSanam JhetamNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On Attrition Rate of InfosysDocument5 pagesA Case Study On Attrition Rate of InfosysArpitaNo ratings yet

- Kumar DeterminantsTalentRetention 2012Document16 pagesKumar DeterminantsTalentRetention 2012Bishnu Bkt. MaharjanNo ratings yet

- A Study On Employee Attrition in BPO Industry in Ahmedabad: AbstractDocument8 pagesA Study On Employee Attrition in BPO Industry in Ahmedabad: AbstractShivang BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Infosys Case StudyDocument14 pagesInfosys Case StudyDeepNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Need For Public-Privatepartnership Pertaining To Formal Employeetraining in Small-Medium Enterprises"Document13 pagesAssessing The Need For Public-Privatepartnership Pertaining To Formal Employeetraining in Small-Medium Enterprises"Son AdamNo ratings yet

- Attrition in The BPODocument7 pagesAttrition in The BPOVijaya Prasad KS100% (4)

- Turnaround ManagementDocument8 pagesTurnaround ManagementaimyNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: IT Sector". The Most Challenging Job For Any Present Manager Is To RetainDocument97 pagesExecutive Summary: IT Sector". The Most Challenging Job For Any Present Manager Is To RetainyashpatiNo ratings yet

- Employee Retention StrategiesDocument46 pagesEmployee Retention StrategiesArun KCNo ratings yet

- A Legal Perspective On Mergers & Acquisitions For Indian BPO IndustryDocument12 pagesA Legal Perspective On Mergers & Acquisitions For Indian BPO IndustryamithasnaniNo ratings yet

- Startup Ecosystem in India and Role of Educational InstitutionsDocument33 pagesStartup Ecosystem in India and Role of Educational InstitutionsNandita SethiNo ratings yet

- Abt D StudyDocument9 pagesAbt D StudyShankar ChinnusamyNo ratings yet

- Indonesia's Efforts To Achieve Globally Competitive Human ResourcesDocument6 pagesIndonesia's Efforts To Achieve Globally Competitive Human ResourcesJean VuNo ratings yet

- Project Employee EngagementDocument34 pagesProject Employee EngagementSuruchi Goyal86% (7)

- Employee RetentionDocument18 pagesEmployee RetentionMunish NagarNo ratings yet

- Attrition and Retention of Employees in Bpo SectorDocument10 pagesAttrition and Retention of Employees in Bpo SectorsachinNo ratings yet

- HR Practices in It Sector - An Overview: Dr. (MRS) K. Malar Mathi Mrs. G. MalathiDocument8 pagesHR Practices in It Sector - An Overview: Dr. (MRS) K. Malar Mathi Mrs. G. MalathiAnurag SinghNo ratings yet

- HRM301 Group 5 Term PaperDocument21 pagesHRM301 Group 5 Term PaperMd. Shahriar Haque ShishirNo ratings yet

- India's Growing Workforce and Evolving HRM PracticesDocument13 pagesIndia's Growing Workforce and Evolving HRM PracticesNeerajNo ratings yet

- A Critical Study On Work-Life Balance of BPO Employees in IndiaDocument12 pagesA Critical Study On Work-Life Balance of BPO Employees in IndiaarunsanskritiNo ratings yet

- 509 ArticleText 886 1 10 20191111Document8 pages509 ArticleText 886 1 10 20191111digitalamplifyphNo ratings yet

- HRM 460 AssignmentDocument13 pagesHRM 460 AssignmentAavez AfshanNo ratings yet

- NTCC ReportDocument21 pagesNTCC ReportIndranil PaulNo ratings yet

- Employee Retention Strategies for Chaudhary GroupDocument10 pagesEmployee Retention Strategies for Chaudhary GroupTrishna SinghNo ratings yet

- Employee Engagement ProjectDocument67 pagesEmployee Engagement Projectboidapu kanakarajuNo ratings yet

- Final Research ProjectDocument69 pagesFinal Research ProjectJatis AroraNo ratings yet

- PM NQ10203Document6 pagesPM NQ10203Raches SelvarajNo ratings yet

- dokumen.tips_hr-practices-at-hulDocument48 pagesdokumen.tips_hr-practices-at-hulKashish barjatyaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Employee Retention Strategies in IndustryDocument18 pagesEffectiveness of Employee Retention Strategies in IndustryLuther KingNo ratings yet

- HRM MergedDocument74 pagesHRM MergedTrâm NgọcNo ratings yet

- Leadership in A Rapidly Changing World: How Businesses in India Are Reframing SuccessDocument28 pagesLeadership in A Rapidly Changing World: How Businesses in India Are Reframing SuccessjvbakshiNo ratings yet

- IT salaries down 20% for fresh recruits amid economic slowdownDocument27 pagesIT salaries down 20% for fresh recruits amid economic slowdownShahbaz AnsariNo ratings yet

- Final Report-IAMAI 40Document60 pagesFinal Report-IAMAI 40ooanalystNo ratings yet

- START-UPS IN INDIA AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE GROWTH OF THE ECONOMYDocument11 pagesSTART-UPS IN INDIA AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE GROWTH OF THE ECONOMYpoovizhikalyani.m2603No ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Employee Retention Strategies in Industry: SSRN Electronic Journal October 2012Document19 pagesEffectiveness of Employee Retention Strategies in Industry: SSRN Electronic Journal October 2012treasure ROTYNo ratings yet

- Project Report ON: "A Study On Employee Engagement HDFC Bank Lucknow"Document93 pagesProject Report ON: "A Study On Employee Engagement HDFC Bank Lucknow"Pratik ShindeNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Corporate GovernanceDocument39 pagesProject Report On Corporate GovernanceRahul MittalNo ratings yet

- 4 ChaptersDocument248 pages4 ChaptersrajeNo ratings yet

- Captives in India Complete ReportDocument97 pagesCaptives in India Complete ReportVishalDogra0% (6)

- The IT Sector Having A CAGR of Over 24Document8 pagesThe IT Sector Having A CAGR of Over 24ayeshaaqueelNo ratings yet

- CASE-Indian Staffing Industry (SWOT Analysis) : Submitted By: - Aparna Singh - 19021141023 M.B.A. (2019-21)Document6 pagesCASE-Indian Staffing Industry (SWOT Analysis) : Submitted By: - Aparna Singh - 19021141023 M.B.A. (2019-21)Aparna SinghNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Globalization On Communication and EducationDocument2 pagesThe Impact of Globalization On Communication and EducationArmel Bacdayan LacanariaNo ratings yet

- Agenda 2000Document184 pagesAgenda 2000Anonymous 4kjo9CJ100% (1)

- Managing global change and diversity in organizationsDocument10 pagesManaging global change and diversity in organizationsrahil2112No ratings yet

- Malaysia's Economic Globalization and the Impact on EducationDocument34 pagesMalaysia's Economic Globalization and the Impact on EducationSiti MusfirahNo ratings yet

- Major Theories of Development Studies: by Ms. Bushra AmanDocument56 pagesMajor Theories of Development Studies: by Ms. Bushra AmanamnaNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Session 3.1 - Global Divides - The North and The SouthDocument3 pagesUnit 3 - Session 3.1 - Global Divides - The North and The SouthEvangeline HernandezNo ratings yet

- Globalisation, Society and Inequalities: Harish WankhedeDocument6 pagesGlobalisation, Society and Inequalities: Harish WankhedesofiagvNo ratings yet

- Cbse Self Study in Social ScienceDocument20 pagesCbse Self Study in Social ScienceYashika verma100% (4)

- Engineering Ethics and Regulations in MalaysiaDocument48 pagesEngineering Ethics and Regulations in MalaysiaAnonymous 5YMOxVQ50% (2)

- Chapter in Smelser-Baltes 2001Document8 pagesChapter in Smelser-Baltes 2001Virendra Mahecha100% (1)

- Pakeha Identity Material CultureDocument15 pagesPakeha Identity Material CultureKinnonPangNo ratings yet

- Integral HumanismDocument9 pagesIntegral HumanismKedar Bhasme100% (1)

- Tom Tat Chapter 6 CSRDocument5 pagesTom Tat Chapter 6 CSRHương MaryNo ratings yet

- Assignment QP MBA International Financial Management MF0015 Summer2013Document2 pagesAssignment QP MBA International Financial Management MF0015 Summer2013Arvind KNo ratings yet

- Cold War Culture in Asian Spies FilmsDocument22 pagesCold War Culture in Asian Spies FilmsAnil MishraNo ratings yet

- 2015 Book RoadmapToSustainableTextilesAnDocument200 pages2015 Book RoadmapToSustainableTextilesAnChai Ting TanNo ratings yet

- Armando Navarro - The Immigration Crisis - Nativism, Armed Vigilantism, and The Rise of A Countervailing Movement (2008)Document529 pagesArmando Navarro - The Immigration Crisis - Nativism, Armed Vigilantism, and The Rise of A Countervailing Movement (2008)Hammouddou ElhoucineNo ratings yet

- HDR 2004Document302 pagesHDR 2004Piyush PoddarNo ratings yet

- Transnational Management Text Cases and Readings in Cross Border Management 7th Edition Bartlett Test BankDocument12 pagesTransnational Management Text Cases and Readings in Cross Border Management 7th Edition Bartlett Test Banka100789669No ratings yet

- C1951 GLDocument30 pagesC1951 GLArnu Felix CamposNo ratings yet

- AP Comp Gov Study GuideDocument42 pagesAP Comp Gov Study GuideHMK86% (7)

- Factors Affecting Fluctuations in China's Aquatic Product Exports To Japan, The USA, South Korea, Southeast Asia, and The EUDocument27 pagesFactors Affecting Fluctuations in China's Aquatic Product Exports To Japan, The USA, South Korea, Southeast Asia, and The EUnhathong.172No ratings yet

- GlobalizationDocument138 pagesGlobalizationThe JC Student100% (1)

- HR Strategic Plan Drives ExcellenceDocument4 pagesHR Strategic Plan Drives ExcellenceKim GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Robertson and Ritzer's Theories of GlobalizationDocument16 pagesRobertson and Ritzer's Theories of Globalizationmaelyn calindongNo ratings yet

- Managing Global Expansion FrameworkDocument5 pagesManaging Global Expansion Frameworklaszlobock100% (1)

- Officer International TaxationDocument19 pagesOfficer International TaxationIsaac OkengNo ratings yet

- International Relations and Diplomacy (ISSN2328-2134) Volume 8, Number 10,2020Document49 pagesInternational Relations and Diplomacy (ISSN2328-2134) Volume 8, Number 10,2020International Relations and DiplomacyNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics and Governance ObjectivesDocument3 pagesPhilippine Politics and Governance ObjectivesAnnalie Delera Celadiña100% (3)

- Arts1090 Research EssayDocument6 pagesArts1090 Research EssayLisaNo ratings yet