Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Buddha's Teaching As It Is - Bhikkhu Bodhi

Uploaded by

sati0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

407 views44 pagesPowrpoint presentation of the lecture on 'Buddha', prepared for Dhamma Study using recorded lectures on 'Buddh's teaching As It Is' given by Bhikkhu Bodhi, for the welfare and happiness of many'

Original Title

The Buddha

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPowrpoint presentation of the lecture on 'Buddha', prepared for Dhamma Study using recorded lectures on 'Buddh's teaching As It Is' given by Bhikkhu Bodhi, for the welfare and happiness of many'

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

407 views44 pagesBuddha's Teaching As It Is - Bhikkhu Bodhi

Uploaded by

satiPowrpoint presentation of the lecture on 'Buddha', prepared for Dhamma Study using recorded lectures on 'Buddh's teaching As It Is' given by Bhikkhu Bodhi, for the welfare and happiness of many'

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 44

Buddha’s Teaching As It Is –

Lecture 1: Buddha Bhikkhu Bodhi

PowerPoint presentation on Bhikkhu Bodhi’s

recorded lectures on ‘Buddha’s Teaching As It Is’.

Materials for the presentation are taken from the

recorded lectures (MP3) posted at the website of

Bodhi Monastery and the notes of the lectures

posted at beyondthenet.net

Originally prepared to accompany the playing of

Bhikkhu Bodhi’s recorded lectures on ‘Buddha’s Teaching

As It is’ in the Dharma Study Class at PUTOSI Temple,

Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia.

This series of weekly study begins in November, 2010.

THE BUDDHA

Bhikkhu Bodhi

Lecture 1

THE BUDDHA – PART I

Bhikkhu Bodhi

UNDERSTANDING AND PRACTICE

Learn to have knowledge (pariyatti) and right

understanding and practice are essential to achieve the

goal of Buddha’s teachings, liberation from suffering.

Wisdom is the key to realisation, developed in three stages:

1. Wisdom born of learning the doctrinal framework;

2. Wisdom born of reflection - examine and explore the

teachings we have learned, and check them out against

our own experience, and verification

3. Wisdom born of meditation

The present course is to lay down the fundamentals of

Buddha’s teachings which are essential as foundation

for the practice.

DHAMMA – THE BUDDHA’S TEACHING

The Buddha’s teaching is called the Dhamma. The word,

‘Dhamma’ means that which sustain, to uphold. The word

signifies the Truth realised by the Buddha; it is a truth that

subsists by itself, the true nature of phenomena. The word

also signifies the path that leads to the realisation of the

Truth, and the doctrines that elucidate the Truth. The Buddha

does not create but that he discovers the Dhamma and

makes it known to the world.

The presentation of the Dhamma in the lectures to follow is

made from the standpoint of the Theravada school of

Buddhism. The principle source of the talks is the Tripitaka –

Sutta Pitaka, Vinaya Pitaka, and Abhidhamma Pitaka. The

main source relied on is Sutta Pitaka and the commentaries.

THE BUDDHA

The Buddha says,

‘The one who sees the Buddha sees the Dhamma’. The

deeper we understand the nature of the Buddha, the

deeper we understand the Dhamma. The converse is also

true.

The word "Buddha" is not a proper name but an honorific

title meaning "the Enlightened One" or "the Awakened

One.“ He is the founder and proclaimer of Truth. The title

is bestowed on the Indian sage Siddhartha Gautama,

who lived and taught in northeast India in the fifth century

B.C. From the historical point of view, Gautama is the

Buddha, the founder of the spiritual tradition known as

Buddhism.

“BUDDHA”

However, from the standpoint of classical Buddhist doctrine,

the word "Buddha" has a wider significance than the title

of one historical figure. The word denotes, not just a

single religious teacher who lived in a particular epoch,

but a type of person -- an exemplar -of which there have

been many instances in the course of cosmic time. The title

"Buddha" is in a sense a "spiritual office," applying to all

who have attained the state of Buddhahood. The Buddha

Gautama, then, is simply the latest member in the spiritual

lineage of Buddhas, which stretches back into the dim

recesses of the past and forward into the distant horizons

of the future.ave been many instances in the course of

cosmic time.

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

What is a Buddha? What are the distinguishing qualities of

a Buddha. The question can be considered from the

standpoints of functions and qualities.

To understand this point more clearly requires a short

excursion into Buddhist cosmology. The Buddha teaches

that the universe is without any discoverable beginning in

time: there is no first point, no initial moment of creation.

Through beginningless time, world systems arise, evolve,

and then disintegrate, followed by new world systems

subject to the same law of growth and decline. The time

from the emergence of the world system to the time it

completely dissolves is called a ‘kalpa’ (aeon).

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

Each world system consists of numerous planes of existence

inhabited by sentient beings similar in most respects to

ourselves. Besides the familiar human and animal realms, it

contains heavenly planes ranged above our own, realms of

celestial bliss, and infernal planes below our own, dark

realms of pain and misery. In all planes of existence life is

impermanent, subject to aging, decay, and death, just as

the world system itself. Even life in the heavens, though long

and blissful, does not last forever. Every existence

eventually comes to an end, to be followed by a rebirth

elsewhere. The beings dwelling in these realms pass from

life to life in an unbroken process of rebirth called samsara,

a word which means "the wandering on."

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

All life is caught up in the cycle of arising and passing

away; all life is impermanent and unsatisfactory.

Therefore, when closely examined, all planes and modes

of existence within samsara reveal themselves as flawed,

stamped with the mark of imperfection, impermanent,

subject to dukkha.

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

However, beyond the conditioned spheres of rebirth, there is

also a realm or state of perfect bliss and peace, of

complete spiritual freedom, a state that can be realized

right here and now even in the midst of this imperfect

world. This state is called Nirvana (in Pali, Nibbana), the

"going out" of the flames of greed, hatred, and delusion.

There is also a path, a way of practice, that leads from the

suffering of samsara to the bliss of Nirvana; from the

round of ignorance, craving, and bondage, to

unconditioned peace and freedom. This is the Noble

Eightfold Path. In the history any particular world system

when this path is known and followed, and some would

attain Nibbana.

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

In time this path will be lost to the world, utterly unknown,

and thus the way to Nirvana will be inaccessible. From

time to time, however, there arises within the world a man

who, by his own unaided effort and keen intelligence,

finds the lost path to deliverance. Having found it, he

follows it through to its end, realises Nibbana, and fully

comprehends the ultimate truth about the world. Then he

returns to humanity and teaches this truth to others,

making known once again the path to the highest bliss.

The person who exercises this function – twofold functions

of discovering the Path and proclaiming it to the world -

is a Buddha.

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

A Buddha is thus not merely an Enlightened One, but is

above all an Enlightener, a World Teacher. His function is

to rediscover, in an age of spiritual darkness, the lost path

to Nirvana, to perfect spiritual freedom, and teach this

path to the world at large. Thereby others can follow in his

steps and arrive at the same experience of emancipation

that he himself achieved. A Buddha is not unique in

attaining Nirvana. All those who follow the path to its end

realize the same goal. Such people are called arahants,

"worthy ones," because they have destroyed all ignorance

and craving.

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

The unique role of a Buddha is to rediscover the Dharma,

the ultimate principle of truth, and to establish a

"dispensation" or spiritual heritage to preserve the

teaching for future generations. So long as the teaching is

available, those who encounter it and enter the path can

arrive at the goal pointed to by the Buddha as the

supreme good.

BUDDHA – QUALITIES

The qualities of the Buddha can be dealt with from two

angles – elimination of all defects; and achievement of

excellent qualities.

The Buddha has eradicated completely and irreversibly all

mental defilements (kilesa) – greed, hatred, delusion, etc.

The Buddha is distinguished also by the three excellent

qualities:

1. Perfect purity in body, speech and mind.

2. Great wisdom in depth and range – knower of the

world; his knowledge encompasses countless world

systems; minds of all living beings.

3. Great compassion - works to alleviate the sufferings of

living beings – teach out of compassion.

BUDDHA – FUNCTIONS AND QUALITIES

In summary, the Buddha is a world teacher, functions to discover

the Dhamma Truth and Path, proclaims and teaches it to the

world, lead sentient beings to liberation.

In terms of quality, the Buddha is one who eliminated all mental

defilements and has acquired excellent qualities -perfect purity,

perfect wisdom and great compassion.

Those who attain enlightenment through the instructions of Buddha

are called arahats, accomplished followers of Buddha.

The Buddha is one who discovers the Path without a teacher and

proclaims it to others. The Buddha also has outstanding

qualities, powers and knowledge that the arahats do not have.

There can be only one Buddha but many arahats in one historical

period.

THE BUDDHA – PART II

Bhikkhu Bodhi

HISTORICAL BUDDHA

The historical Buddha is known as Siddhartha Gautama (his

given names) or Buddha Gautama or Buddha Sakyamuni.

While we do not know the exact dates of his life, many

scholars believe he lived from approximately 563 to 483

B.C.; a smaller number place the dates about a century

later.

From traditional Buddhist perspective, the story of the

Buddha goes back many aeons into the past. To qualify

as a Buddha, a World Teacher, an aspirant must prepare

himself over an inconceivably long period of time

spanning countless lives. During these past lives, the future

Buddha is referred to as a bodhisattva, an aspirant to

the full enlightenment of Buddhahood.

PREPARING FOR BUDDHAHOOD

In each life the bodhisattva must train himself, through

altruistic deeds and meditative effort, to acquire the

qualities or virtues essential to a Buddha. These qualities

are called påramis or påramitås, transcendent virtues or

perfections. Different Buddhist traditions offer slightly

different lists of the påramis. In the Theravada tradition

they are said to be tenfold: generosity, moral conduct,

renunciation, wisdom, energy, patience, truthfulness,

determination, loving-kindness, and equanimity. In each

existence, life after life through countless cosmic aeons, a

bodhisattva must cultivate these sublime virtues in all their

manifold aspects to perfection.

PREPARING FOR BUDDHAHOOD

Sometimes he would dedicate several lives in succession to

perfect a particular virtue. Sometimes, he would appear

as an animal, a human being, a deity. Sometimes he

would be striving to develop concentration and insight

and other virtues. Buddhahood is a totalistic

accomplishment. All the qualities are perfected over

many life times.

In his last life as a Bodhisatta, he took birth as the son of

King Sudhodana and Queen Mahamaya in the Sakyan

clan. He was born as Siddhartha Gautama in the small

Sakyan republic close to the Himalayan foothills, a region

that at present lies in southern Nepal. He was born in

Lumbini. He grew up in Kapilavatthu. His birth was

attended by many miracles and wonders.

BIRTH AND QUEST FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

His father called in four court astrologists to foretell the

son’s future. All the astrologists except one predicted that

two possible great destinies for the child. If shielded

from the sorrows of the world, he would grow up to be a

universal monarch who would extend his rule over many

lands and bring benefits to many people. If the child

sees for himself the sufferings of the world, he would

leave the household life to become a Buddha whose

teachings would spread throughout the world. The one

remaining Brahmin has no doubt that the child would

become a Buddha. His father shielded the son from all

sufferings of the world, built him palaces, and ensured

him a life of luxuries and shelter.

BIRTH AND QUEST FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

As a royal youth, Prince Siddhartha was raised in luxury. At

the age of sixteen he married a beautiful princess named

Yasodhara and lived a contented life in the capital,

Kapilavatthu. Over time, however, the prince became

increasingly pensive. What troubled him were the great

burning issues we ordinarily take for granted, the

questions concerning the purpose and meaning of our

lives. Do we live merely for the enjoyment of sense

pleasures, the achievement of wealth and status, the

exercise of power? Or is there something beyond these,

more real and fulfilling?

THE FOUR SIGHTS

According to a myth that expresses a real and powerful

psychological awakening, up to his 29th year, Prince

Siddhartha was completely hidden from aging, sickness, the

hard facts of life. During his outing, he saw four sights which

determined his future destiny:

1. Ageing – he saw an old man;

2. Sickness – he saw a sick man;

3. Death – he saw a funeral procession, a corpse.

These sights shattered all his delusions. He became very

discontent.

4. Ascetic – a recluse living a life of meditation seeking a way

to deliverance from suffering

QUEST FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

The prince now knew the direction he must move. The night

of the very day his son Rahula was born, at the age of

29, he left the palace. He entered the forest, cut off his

hair and beard, put on the saffron robe, and entered

upon the homeless life of renunciation, seeking a way to

release from the round of repeated birth, old age, and

death.

At the age of 29, stirred by deep reflection on the hard

realities of life, he decided that the quest for illumination

had a higher priority than the promise of power or the

call of worldly duty.

QUEST FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

At the time northern India could boast a number of

accomplished masters famous for their philosophical

systems and skills in meditation. Prince Siddhartha sought

out two of the most eminent, Alara Kalama and Uddaka

Ramaputta. The Bodhisatta mastered their teachings and

systems of meditation. He found that this led to deep

states of concentration (samadhi), but not insight into the

true nature of things. he found these teachings did not

lead to the goal he was seeking: perfect enlightenment

and the realization of Nibbana, release from the sufferings

of mundane existence. The bodhisattava abandoned these

teachers.

QUEST FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

Having left his teachers, the Bodhisatta adopted a different path,

one that was popular in ancient India and still has followers

today: the path of asceticism, of self-mortification, pursued in

the conviction that liberation is to be won by afflicting the body

with pain beyond its normal levels of endurance. For six years

the Bodhisatta followed this method with unyielding

determination. He fasted for days on end until his body looked

like a skeleton cloaked in skin; he exposed himself to the heat

of the midday sun and the cold of the night; he subjected his

flesh to such torments that he came almost to the door of death.

Yet he found that despite his persistence and sincerity these

austerities were futile. Later he would say that he took the path

of self-mortification further than all other ascetics, yet it led, not

to higher wisdom and enlightenment, but only to physical

weakness and the deterioration of his mental faculties.

QUEST FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

Just then he thought of another path to enlightenment, one

which balanced proper care of the body with sustained

contemplation and deep investigation. He would later call

this path "the Middle Way," because it avoids the

extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification. He

had experienced both extremes, the former as a prince

and the latter as an ascetic, and he knew they were

ultimately dead ends. To follow the Middle Way,

however, he realized he would first have to regain his

strength. Thus he gave up his practice of austerities and

resumed taking nutritious food. At the time five other

ascetics had been living in attendance on the Bodhisatta,

hoping that when he attained enlightenment he would

serve as their guide.

QUEST FOR ENLIGHTENMENT

But when they saw him partake of substantial meals, they

became disgusted with him and left him, thinking the

princely ascetic had given up his exertion and reverted to

a life of luxury. Now he was alone, and complete solitude

allowed him to pursue his quest undisturbed.

One day, when his physical strength had returned, he

approached a lovely spot in Uruvela by the bank of the

Neranjara River. Here he prepared a seat of straw

beneath an asvattha tree (later called the Bodhi Tree)

and sat down cross-legged, making a firm resolution that

he would never rise up from that seat until he had won his

goal.

MARA – INTERNAL STRUGGLES

Then the struggle for enlightenment took place in the mind of the

seeker, a struggle against all defilements and all afflictions. In

the text, the struggle was depicted allegorically as a battle with

Mara, the personification of all desire and attachment, the

tempter, the evil one. Mara called in all his army and hordes of

demons, tempting him with honor, power and fame, sovereignty

over the whole world; appeals to his love of family life; tries to

frighten him with thunder, lightning; tries to seduce him with

delight and pleasures; challenges his right to sit under the Bodhi

tree. The seeker pointed to the earth as his witness – his right

hand touching the ground, the fulfillment of his paramis.

As night descended he entered into deeper and deeper stages of

jhana until his mind was perfectly calm and composed.

ENLIGHTENMENT

Then, the records tell us,

in the first watch of the night he directed his tranquil mind

to the recollection of his previous lives, and there

unfolded before his inner vision his experiences in many

past births, even during many cosmic aeons;

in the middle watch of the night he developed the "divine

eye" by which he could see beings rising and passing

away; and beings taking rebirth in accordance with their

karma, their deeds;

and in the last watch of the night he penetrated the deepest

truths of existence, the most basic laws of reality, the law

of dependent arising, he developed vipassana and

realised the Four Noble Truths, and thereby removed from

his mind the subtlest veils of ignorance.

ENLIGHTENMENT

When dawn broke, the figure sitting beneath the tree was

no longer a Bodhisatta, a seeker of enlightenment, but a

Buddha, a Fully Enlightened One, one who had attained

the Deathless in this very life itself.

For several weeks the newly awakened Buddha remained in

the vicinity of the Bodhi Tree contemplating from different

angles the Dhamma (Skt: Dharma), the truth he had

discovered. Then he came to a new crossroad in his

spiritual career: Was he to teach, to try to share his

realization with others, or should he instead remain

quietly in the forest, enjoying the bliss of liberation alone?

ENLIGHTENMENT – INSIGHT & WISDOM

At first his mind inclined to keeping quiet; for he thought the

truth he had realized was just too deep for others to

understand, too difficult to express in words, and he was

concerned he would just weary himself trying to convey

his realization to others. But now the texts introduce a

dramatic element into the story. Just at the moment the

Buddha decided to remain silent, a high deity named

Brahma Sahampati, the Lord of a Thousand Worlds,

realized that if the Master remained silent the world

would be lost, deprived of the stainless path to

deliverance from suffering. Therefore he descended to

earth, bowed down low before the Awakened One, and

humbly pleaded with him to teach the Dhamma "for the

sake of those with little dust in their eyes."

COMPASSION FOR THE WORLD

The Buddha then gazed out upon the world with his

profound vision. He saw that people are like lotuses in a

pond at different stages of growth, and he understood

that just as some lotuses close to the surface of the water

need only the sun’s rays to rise above the surface and

blossom fully, so there are some people who need only to

hear the teaching in order to win enlightenment and gain

perfect liberation of mind. When he saw this his heart

was stirred by deep compassion, and he decided to go

forth back into the world and to teach the Dhamma to

those who were ready to listen.

THE BUDDHA’S MISSION

The first ones he approached were his former companions,

the five ascetics who had deserted him a few months

earlier and were now dwelling in a deer park at Sarnath

near Varanasi. He explained to them the truths he had

discovered, and on hearing his discourse they gained

insight into the Dhamma, he explained the Middle Way in

his first discourse, then the Four Noble Truths. On hearing

his discourses, the five ascetics gained insight into the

Dhamma, gained insight into the Dhamma, attained

various stages of enlightenment and finally arahatship.

In the months ahead his following grew by leaps and

bounds as both householders and ascetics heard the

liberating message, gave up their former creeds, and

declared themselves disciples of the Enlightened One.

COMPASSION FOR THE WORLD

At the end of the first rains retreat, the Buddha gathered the

sixty disciples who were all arahats around him and sent

them out to the world, each in a different direction to spread

the liberating message of the Dhamma.

In his talks, he emphasised compassion as the motive for his

teaching. He said, “monks, I am free from all fetters, human

and divine. You too are free from all fetters. Therefore go

forth into the world, for the good of many folks, for the

happiness of the many folks out of compassion for the world,

and teach the Dhamma, make know the Dhamma which is

pure in the beginning, pure in the middle and pure in the

end. Teach the holy life, completely purified and perfect.’

THE BUDDHA’S MISSION

Each year, even into his old age, he would wander among the

villages, towns, and cities of the Ganges plain, teaching all

who would lend an ear; he would rest only for the three

months of the rainy season (often at Jetavanna near Savatthi

or the Bamboo Grove in Rajagaha), and then resume his

wanderings, which took him from present Delhi even as far

east as Bengal.

In the second year after his enlightenment, he returned to

Kapilavatthu and taught the Dhamma to his family and

relatives. Many including his father reached various stages

of enlightenment. His son, Rahula became a novice monk and

later bhikkhu; his wife, Yasodhara became a bhkkhuni.

THE BUDDHA’S MISSION

He established a Sangha, an order of monks and nuns, for

which he laid down an intricate body of rules and

regulations; this order still remains alive today, perhaps

(along with the Jain order) the world’s oldest continuous

institution. He also attracted many lay followers who

became devoted supporters of the Master and his

Sangha.

After an active ministry of 45 years, at the ripe age of 80,

the Buddha headed for the northern town of Kusinara.

There, surrounded by many disciples, he passed away

into the Nibbana element with no remainder of

conditioned existence, severing forever his connection to

the round of rebirths.

APPEAL OF BUDDHA’S TEACHING

To ask why the Buddha's teaching spread so rapidly among

all sectors of northeast Indian society is to raise a

question that is not of merely historical interest but is also

relevant to us today. For we live at a time when Buddhism

is exerting a strong appeal upon an increasing number of

people, both East and West. I believe the remarkable

success of Buddhism, as well as its contemporary appeal,

can be understood principally in terms of two factors:

one, the aim of the teaching; and the other, its

methodology.

AIM OF BUDDHA’S TEACHING

As to the aim, the Buddha formulated his teaching in a way

that directly addresses the central problem at the heart

of human existence – the universal problem of suffering --

and does so without reliance upon the myths and

mysteries so typical of religions. He further shows the way

to the end of sufferings, to perfect peace and

unconditioned happiness. All other concerns apart from

this, such as theological dogmas, metaphysical subtleties,

rituals and rules of worship, the Buddha waves aside as

irrelevant to the task at hand, the mind's liberation from

its bonds and fetters. He deals with the problem of

suffering in a realistic way, personal and verifiable.

SELF-RELIANCE

He traces the suffering to its roots in our own mind, greed,

hatred and delusion; and that the solution has to be

found in the mind by purifying it of the defilements. As a

result of this diagnosis, the Buddha rejects all extraneous

religious forms which involve external reliance such as the

performance of rituals and sacrifices; appeal to

authoritative books; reliance on priests and saviours; and

reliance on divine figures to grant salvation.

The Buddha emphasises that self-reliance is the key to

deliverance. He says to his disciples, ‘be island to

yourself; be a refuge to yourself; look to no external

refuge.’

SELF-RELIANCE

As a way to deliverance, he holds up purified conduct and

correct understanding. The Buddha functions as a

teacher, not as a savior who grants salvation. The path to

deliverance has to be followed each one by himself

according to his own energy and understanding.

For these reasons, the Buddha rejects the call for blind faith

and belief. He asked his followers not to accept his

teachings out of faith or respect, but to examine,

investigate and verify it before accepting it.

UNIVERSALITY OF BUDDHA’S TEACHING

Universality. Because the Buddha’s teaching deals with the

most universal of all human problems, the problem of

suffering, he made his teaching a universal message, one

which was addressed to all human beings solely by

reason of their humanity. The Buddha placed no

restrictions on the people to whom he taught the Dhamma.

He held that what made a person noble was his personal

qualities and conduct, not his family and caste status. Thus

he opened the doors of liberation to people of all social

classes. Brahmins, kings and princes, merchants, farmers,

workers, even outcasts – all were welcome to hear the

Dhamma without discrimination, and many from the lower

classes attained the highest stage of enlightenment.

SKILFUL MEANS OF THE BUDDHA

To understand the success of the Buddha’s mission there is

one further feature of his method that we must take into

account. This is what might be called his "skilful means.“

Through his complete enlightenment, the Buddha had

gained the special ability to discover the precise way to

teach the people who came to him for guidance. He could

read deep into the hidden recesses of people’s heart,

perceive their aptitudes and interests, and frame his

teaching in the exact way needed to transform them and

lead them on to the path of freedom. The texts abound in

many examples of this supreme pedagogic skill of the

Buddha.

PARINIRVANA AND AFTERWARDS

The Buddha taught for 45 years. He had accomplished his

mission, his doctrines became widespread and fruitful; he

had established a sangha and followers who had

mastered the teaching. In his 80th year as he prepared to

pass into parinirvana, he set out to Kusinara with his

disciples. He laid down between two twin sal trees,

exhorted his disciples, ‘all conditioned things are

impermanent, subject to destruction; work out your own

salvation with diligence.’ these were the Buddha’s last

words, entered into successive stages of concentration

and from there entered into parinirvana. His body was

cremated with the full honor due to a universal monarch.

You might also like

- Mahayana TeachingsDocument88 pagesMahayana Teachingssimion100% (2)

- Tranquillity Leading to Insight: Exploration of Buddhist Meditation PracticesFrom EverandTranquillity Leading to Insight: Exploration of Buddhist Meditation PracticesNo ratings yet

- Buddha Theravada Buddhism SomaratenaDocument15 pagesBuddha Theravada Buddhism SomaratenaSakisNo ratings yet

- Social Dimension of Buddha's TeachingDocument55 pagesSocial Dimension of Buddha's Teachingsati100% (4)

- Rebirth and KammaDocument91 pagesRebirth and KammasatiNo ratings yet

- The True Nature of ExistenceDocument31 pagesThe True Nature of Existencesati100% (1)

- Pali Second Year AllDocument390 pagesPali Second Year AllDanuma Gyi100% (2)

- The Word Of The Buddha; An Outline Of The Ethico-Philosophical System Of The Buddha In The Words Of The Pali Canon, Together With Explanatory NotesFrom EverandThe Word Of The Buddha; An Outline Of The Ethico-Philosophical System Of The Buddha In The Words Of The Pali Canon, Together With Explanatory NotesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- L8 MeditationDocument66 pagesL8 MeditationsatiNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Dhammacakkappavattana S s56.11Document26 pages1.1 Dhammacakkappavattana S s56.11Piya_Tan100% (1)

- SanghaDocument63 pagesSanghasatiNo ratings yet

- Investigating Suffering and the TeacherDocument2 pagesInvestigating Suffering and the TeacherKongmu ShiNo ratings yet

- An Exposition of The Metta Sutta PDFDocument22 pagesAn Exposition of The Metta Sutta PDFBinh AnsonNo ratings yet

- In The Buddha's Words - Course Notes Chapter 8 Lessons 1-3Document4 pagesIn The Buddha's Words - Course Notes Chapter 8 Lessons 1-3Kongmu ShiNo ratings yet

- The Classification of TipitakaDocument62 pagesThe Classification of TipitakaFabiana Fabian100% (4)

- Buddhist Mindfulness and Its Role in Early SourcesDocument20 pagesBuddhist Mindfulness and Its Role in Early Sourcesbuddhamieske3100% (1)

- Preface: Baddanta Kumārābhiva SADocument194 pagesPreface: Baddanta Kumārābhiva SAtrungdaongoNo ratings yet

- Narrative ReportDocument20 pagesNarrative ReportHazie Tan0% (1)

- Philosophy of The AtthakavaggaDocument15 pagesPhilosophy of The AtthakavaggaBuddhist Publication Society100% (1)

- Pali Third Year AllDocument291 pagesPali Third Year AllDanuma Gyi50% (2)

- Citta YamakaDocument43 pagesCitta Yamakatrungdaongo100% (1)

- Four Noble TruthsDocument35 pagesFour Noble Truthssati100% (1)

- Bhikkhuni Vinaya StudiesDocument236 pagesBhikkhuni Vinaya Studiessujato100% (2)

- Understanding the Pure Speech of the BuddhaDocument17 pagesUnderstanding the Pure Speech of the BuddhaHan Sang KimNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Ethics: by Mohsen Omar and Sara EmamiDocument13 pagesBuddhist Ethics: by Mohsen Omar and Sara EmamiAmjath JamalNo ratings yet

- Bodhi - Pakkhiya, Dhamma PiyaDocument13 pagesBodhi - Pakkhiya, Dhamma PiyaPiya_TanNo ratings yet

- Development of Vinaya As A PitakaDocument7 pagesDevelopment of Vinaya As A Pitakaanjana12No ratings yet

- A Guide To Pali Texts, Commentaries, and TranslationsDocument4 pagesA Guide To Pali Texts, Commentaries, and TranslationssoftdinaNo ratings yet

- Samyutta Nikaya An Anthology III IndexDocument9 pagesSamyutta Nikaya An Anthology III IndexBuddhist Publication SocietyNo ratings yet

- Four Noble TruthsDocument185 pagesFour Noble TruthsSankha Widuranga Kulathantille100% (2)

- Arhat, Buddha and BodhisattvaDocument21 pagesArhat, Buddha and BodhisattvaSwati S Deshmukh100% (1)

- Patna-Dhammapada, Transcribed by Margaret Cone, 1989Document218 pagesPatna-Dhammapada, Transcribed by Margaret Cone, 1989sebburgNo ratings yet

- Bhikkhu Buddhadasa's Interpretation of The Buddha - Donald K. SwearerDocument25 pagesBhikkhu Buddhadasa's Interpretation of The Buddha - Donald K. SwearerTonyNo ratings yet

- Understanding the First Noble Truth of Suffering (Dukkha) in Early BuddhismDocument5 pagesUnderstanding the First Noble Truth of Suffering (Dukkha) in Early BuddhismSajib BaruaNo ratings yet

- Origin and Evolution of the Theravada AbhidhammaDocument9 pagesOrigin and Evolution of the Theravada AbhidhammaPemarathanaHapathgamuwaNo ratings yet

- Mahavairocana Sutra - ClearscanDocument207 pagesMahavairocana Sutra - ClearscanAyur Montsuregi100% (1)

- Buddhist Books For Free DistributionDocument2 pagesBuddhist Books For Free DistributionAmogha CittaNo ratings yet

- The Seven Factors of Enlightenment by Piyadassi TheraDocument10 pagesThe Seven Factors of Enlightenment by Piyadassi Theramiguel angel100% (1)

- Asanga Tilakaratne: of The Relation Between Religious Experience and Language According To Early Buddhism (1986-1992)Document32 pagesAsanga Tilakaratne: of The Relation Between Religious Experience and Language According To Early Buddhism (1986-1992)Rinuja RinuNo ratings yet

- Comparing Pure Land Teachings in India and ChinaDocument7 pagesComparing Pure Land Teachings in India and ChinadewNo ratings yet

- The Pali Text Society's Pali-English Dictionary. (Ed - Rhys Davids, W.stede) (1921-25)Document806 pagesThe Pali Text Society's Pali-English Dictionary. (Ed - Rhys Davids, W.stede) (1921-25)sktkoshas100% (1)

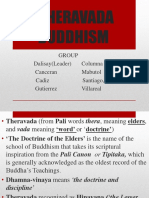

- Theravada BuddhismDocument26 pagesTheravada BuddhismMhay Gutierrez100% (1)

- Samatha & Vipassana in The Theravada Abhidhamma - HuifengDocument32 pagesSamatha & Vipassana in The Theravada Abhidhamma - HuifengTenzin SopaNo ratings yet

- 4 Buddhist CouncilDocument12 pages4 Buddhist CouncilHemant TomarNo ratings yet

- Pali Terms Related To MindDocument3 pagesPali Terms Related To MindHoang NguyenNo ratings yet

- Zen Buddhism: By, Soutsada Sikhounchanh & Sabrina FuentesDocument20 pagesZen Buddhism: By, Soutsada Sikhounchanh & Sabrina FuentesSoutsada SikhounchanhNo ratings yet

- Pali First-Year AllDocument319 pagesPali First-Year AllDanuma Gyi100% (11)

- Book Pali Roots PDFDocument31 pagesBook Pali Roots PDFMai KimNo ratings yet

- The Abhidhamma in Practice - N.K.G. MendisDocument54 pagesThe Abhidhamma in Practice - N.K.G. MendisDhamma Thought100% (1)

- 2016Document186 pages2016Asgiriye Silananda100% (1)

- An Exposition of The Dhammacakka SuttaDocument24 pagesAn Exposition of The Dhammacakka SuttaBinh AnsonNo ratings yet

- Group 8 Silahis, Diana Rose Princess Gadiano, Mary-Ann Meña, AljhunDocument13 pagesGroup 8 Silahis, Diana Rose Princess Gadiano, Mary-Ann Meña, AljhunPrincessNo ratings yet

- What The Nikayas Say About NibbanaDocument34 pagesWhat The Nikayas Say About Nibbanamichaelnyman9999100% (4)

- Noble Eightfold Path Noble Eightfold Path: Morality WisdomDocument30 pagesNoble Eightfold Path Noble Eightfold Path: Morality WisdomsatiNo ratings yet

- Glossary FundamentalAbhidhammaDocument23 pagesGlossary FundamentalAbhidhammaJaywant DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- The Buddha & His Message: PrologueDocument11 pagesThe Buddha & His Message: PrologueopNo ratings yet

- Buddhism: The Wisdom of Compassion and Awakening by Ven. Master Chin KungDocument84 pagesBuddhism: The Wisdom of Compassion and Awakening by Ven. Master Chin KungYau YenNo ratings yet

- Merit-Based Buddhist EconomyDocument2 pagesMerit-Based Buddhist EconomysatiNo ratings yet

- Khang Bu Ya - by Suwida SansehanatDocument7 pagesKhang Bu Ya - by Suwida SansehanatsatiNo ratings yet

- L8 MeditationDocument66 pagesL8 MeditationsatiNo ratings yet

- A Study of Pāramīs - Bhikkhu Bodhi - TranscriptsDocument74 pagesA Study of Pāramīs - Bhikkhu Bodhi - Transcriptssati100% (3)

- Dependent ArisingDocument45 pagesDependent Arisingsati100% (2)

- Lay Buddhist Activism - by Bong C L and Suwida SangsehanatDocument7 pagesLay Buddhist Activism - by Bong C L and Suwida SangsehanatsatiNo ratings yet

- SanghaDocument63 pagesSanghasatiNo ratings yet

- L8 MeditationDocument66 pagesL8 MeditationsatiNo ratings yet

- NibbanaDocument37 pagesNibbanasatiNo ratings yet

- Noble Eightfold PathDocument54 pagesNoble Eightfold Pathsati100% (3)

- The True Nature of ExistenceDocument31 pagesThe True Nature of Existencesati100% (1)

- The True Nature of ExistenceDocument37 pagesThe True Nature of ExistencesatiNo ratings yet

- Producing Your Own EnzymesDocument37 pagesProducing Your Own EnzymessatiNo ratings yet

- Four Noble Truths - by Bhikkhu BodhiDocument34 pagesFour Noble Truths - by Bhikkhu BodhisatiNo ratings yet

- Right Education - Srisa Asoke ModelDocument10 pagesRight Education - Srisa Asoke ModelsatiNo ratings yet

- Four Noble TruthsDocument35 pagesFour Noble Truthssati100% (1)

- Bodhi Vijjalaya - Alternative EducationDocument10 pagesBodhi Vijjalaya - Alternative EducationsatiNo ratings yet

- Development of Wisdom: PA Ã KhandaDocument37 pagesDevelopment of Wisdom: PA Ã KhandasatiNo ratings yet

- Noble Eightfold Path Noble Eightfold Path: Morality WisdomDocument30 pagesNoble Eightfold Path Noble Eightfold Path: Morality WisdomsatiNo ratings yet

- Samma Sati IIIDocument39 pagesSamma Sati IIIsatiNo ratings yet

- Abhidhamma Overview: CetasikasDocument76 pagesAbhidhamma Overview: CetasikassatiNo ratings yet

- Samma Sati IIDocument37 pagesSamma Sati IIsatiNo ratings yet

- Abhidhamma: Rupa & NibbanaDocument92 pagesAbhidhamma: Rupa & Nibbanasati100% (1)

- Sadaranabhogi - A Buddhist Social System As Practiced in Asoke CommunityDocument18 pagesSadaranabhogi - A Buddhist Social System As Practiced in Asoke Communitysati100% (1)

- Samma Sati IDocument19 pagesSamma Sati IsatiNo ratings yet

- Abhidhamma Overview: CetasikasDocument76 pagesAbhidhamma Overview: CetasikassatiNo ratings yet

- Overview of Abhidhamma: CittaDocument95 pagesOverview of Abhidhamma: Cittasati100% (1)

- BURKITT, Ian - The Time and Space of Everyday LifeDocument18 pagesBURKITT, Ian - The Time and Space of Everyday LifeJúlia ArantesNo ratings yet

- UNIT II Project EvaluationDocument26 pagesUNIT II Project Evaluationvinothkumar hNo ratings yet

- Hoarding BestPracticeGuideDocument45 pagesHoarding BestPracticeGuideTheresa SuleNo ratings yet

- Policies - Child ProtectionDocument10 pagesPolicies - Child ProtectionStThomasaBecketNo ratings yet

- Ngo MergeDocument74 pagesNgo MergeYogesh MantrawadiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary WorldDocument1 pageContemporary WorldAngel SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Overview of Language Teaching MethodologyDocument19 pagesOverview of Language Teaching Methodologyapi-316763559No ratings yet

- Lesson 6: Forming All Operational DefinitionsDocument17 pagesLesson 6: Forming All Operational DefinitionsshahiraNo ratings yet

- Visual Design - SyllabusDocument3 pagesVisual Design - Syllabusapi-318913436No ratings yet

- 09590550310465521Document13 pages09590550310465521srceko_15No ratings yet

- Year 12 Re Self-Assessment RubricDocument2 pagesYear 12 Re Self-Assessment Rubricapi-253018194No ratings yet

- EDUCATION IN THAILAND: REFORMS AND ACHIEVEMENTSDocument37 pagesEDUCATION IN THAILAND: REFORMS AND ACHIEVEMENTSManilyn Precillas BantasanNo ratings yet

- Performance Improvement PlanDocument2 pagesPerformance Improvement PlanSimao AndreNo ratings yet

- Quickly Wear The Face of The DevilDocument1,833 pagesQuickly Wear The Face of The DevilKriti Gupta100% (1)

- Problem Diagnosis & Introduction To Project DynamicsDocument42 pagesProblem Diagnosis & Introduction To Project DynamicseviroyerNo ratings yet

- AcknowledgementDocument10 pagesAcknowledgementAnthonio MaraghNo ratings yet

- BOOK3Document4 pagesBOOK3CromwanNo ratings yet

- What Will Improve A Students Memory?Document10 pagesWhat Will Improve A Students Memory?Aaron Appleton100% (1)

- Music Lesson PlanDocument15 pagesMusic Lesson PlanSharmaine Scarlet FranciscoNo ratings yet

- TourguidinginterpretationDocument51 pagesTourguidinginterpretationSiti Zulaiha ZabidinNo ratings yet

- Biopsychology 1.1 1.4Document12 pagesBiopsychology 1.1 1.4sara3mitrovicNo ratings yet

- Bridges FOR Communication AND Information: Reyjen C. PresnoDocument27 pagesBridges FOR Communication AND Information: Reyjen C. PresnoReyjen PresnoNo ratings yet

- A Study of Spatial Relationships & Human ResponseDocument30 pagesA Study of Spatial Relationships & Human ResponseJuan Pedro Restrepo HerreraNo ratings yet

- Ecosoc Chair ReportDocument9 pagesEcosoc Chair Reportapi-408542393No ratings yet

- Admin Assistant Receptionist Job DescriptionDocument4 pagesAdmin Assistant Receptionist Job DescriptionMitTuyetNo ratings yet

- Witch Wars Defense Manual PDFDocument99 pagesWitch Wars Defense Manual PDFAlrica NeshamaNo ratings yet

- Intro to Management FunctionsDocument2 pagesIntro to Management FunctionsRia AthirahNo ratings yet

- Open Research Online: Kinky Clients, Kinky Counselling? The Challenges and Potentials of BDSMDocument37 pagesOpen Research Online: Kinky Clients, Kinky Counselling? The Challenges and Potentials of BDSMmonica cozarevNo ratings yet

- Cutting Edge Intermediate Scope and SequencesDocument4 pagesCutting Edge Intermediate Scope and Sequencesgavjrm81No ratings yet

- 31 MBM Brochure PDFDocument2 pages31 MBM Brochure PDFsachinNo ratings yet