Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Exploring Consumer Perceptions of Visual Distinctiveness: ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 22

Uploaded by

realitymOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Exploring Consumer Perceptions of Visual Distinctiveness: ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 22

Uploaded by

realitymCopyright:

Available Formats

Exploring Consumer Perceptions of Visual Distinctiveness

Elise Gaillard, Jenni Romaniuk and Anne Sharp

Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, University of South Australia.

Abstract

The term ‘distinctiveness’ has been ascribed a number of differing meanings in marketing,

but there is a common element of it being something that makes the brand stand out.

Marketers seek to create distinctive brands and accompanying communication in the hope of

creating greater communication cut-through (and hence effectiveness) and to get the brand

noticed amongst the clutter at the consumer point of purchase. This paper explores consumer

perceptions of what makes a brand distinctive and compares this to perceptions about what

makes an advertisement distinctive. In particular, visual distinctiveness is explored. The

empirical data for this research comes from the banking industry, taking distinctiveness

research into the area of services, where there is little prior research. We found that brand and

advertising distinctiveness were more likely to both gain mentions for a particular brand,

rather than independently for different brands. However, consumers had great difficultly in

articulating what in particular made a brand or advertising distinctive, in terms of specific

elements such as shape or colour. When focusing on the visual elements of distinctiveness,

symbols were the most commonly mentioned element, followed closely by colours. This

research has laid a foundation for understanding how consumers perceive distinctiveness in a

retail service context.

Keywords: branding, distinctiveness, perceptions

Introduction

Although there is no single definition in marketing literature of distinctiveness, a common

element across definitions involves the cues stored in memory that make the brand stand out,

causing consumer recognition of a brand in consumers’ minds (Olson, 2004). This brand

distinctiveness is incredibly important as consumers unconsciously and continually monitor

their surroundings in a process called pre-attentive processing, to discover if anything

captures their attention (Franzen, 1999). Consumers’ surroundings consist of far too many

words and images for them to be able to process and use, leading to the screening out of much

of marketers’ efforts (Heath, 2000). This makes it important for a brand to try and cut-

through this screening out process, through being distinctive in some way. According to

Schruntek, no brand can lead or succeed if it doesn’t stand out and mean something to the

consumer (1999, p. 34)

Another important benefit of distinctiveness is the ability to create and sustain a ‘strong’

identity. It has been said that there is a greater chance a brand will be recognised by more

people if it utilises distinctive recognition cues (Olson, 2004). Further to this, Howard and

Sheth (1969 cited in Rex, 2004) identified that consumers employ a mixture of quality, price

and distinctiveness when making purchase decisions, so it plays a central role in the actual

purchase decision. Moreover, both brand equity and success are dependent on high levels of

brand distinctiveness (Keller 1998 cited in Warlop, Ratneshwar and Osselaer, 2005;

Krishnan, 1996). Distinctiveness makes it easier for the consumer to remember the details of

a brand as it is more noticeable. More specifically, in a recent study, 30 per cent of people

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 22

were able to correctly identify a distinctive theme or slogan, illustrating that it is an important

communication tool (Miller and Berry, 1998).

Advertising distinctiveness refers to a brand’s advertisements (i.e. TV, print and radio) and

includes aesthetic cues such as texture, logo, graphics, country of origin, taglines, themes,

typeface, trademarks, colour, symbols and music. Brand distinctiveness refers specifically to

the brand (i.e. Commonwealth or Bendigo bank) and includes aesthetic cues such as shape,

location, display promotions, colour and store atmospherics which entail the five senses:

sight, sound, scent, touch and taste and can include, for example, employee appearance

(Agres and Dubitsky, 1996; Pfahlert, Hoek and Healey, 2004; Rex, Wai and Lobo, 2004;

Simoes and Dibb, 2001; Miller and Berry, 1998; Ward, Bitner and John, 1992). Distinctive

advertising is said to stimulate interest and contain a catchy and easy to remember slogan that

can capture the nature of the business in a few words (Birchard, 1964). However, there is

constant debate as to the effectiveness of slogans. An exploratory study conducted by

Wateridge and Donaghey (1998) found that the brands that were commonly remembered,

such as Kit Kat’s Have a Break and Nike’s Just do it, by consumers were largely due to

campaign longevity and ad spend.

One element of distinctiveness we particularly focus on in this paper is the visual element. An

identity is usually publicised via a logo and is normally consistent in the brand’s

communication (Van de Laar and Van de Pas, 2002). Visual brand identities are said to guide

and aim the consumer in making their brand choice. Colour is one visual element that has

been suggested as a means of creating distinctiveness and can be registered as a trademark

(Pfahlert, Hoek and Healey, 2004; Plasschaert and Floet, 1995). The cleaning and hygiene

industry has recently exploded with companies attempting to register their colours for

washing machine tablets as trademarks (Playle and Hodson, 2003). Although there has been

an array of research on colour in the areas of packaging and design, the use of colour in

service markets has been limited. Additionally, there is little known about the application of

colour in store environments. This has caused many retailers to rely on subjective judgments

or the packaging and design research to make their decisions. Further to this, the ability to

create a distinctive image through visual elements, such as the physical environment is

particularly relevant for service businesses such as banks.

In summary, there is debate within marketing and advertising literature about which elements

create a distinctive brand/advertisement. There is also little published empirical investigation

of what constitutes distinctiveness from the consumer’s perspective. Therefore, research is

needed to gain an insight as to what consumers see as distinctive about advertising and

brands. This paper explores this issue, with a particular focus on the visual elements of the

brand in a retail service setting.

Methodology

We selected the banking industry as our service industry to research. This was because there

are a myriad of competing brands in the market that use different visual elements, such as

colours and symbols, in the hope of being distinctive. We chose seven of the largest banking

brands in Australia to research. Three research questions were proposed for visual

distinctiveness in the banking industry: Firstly, what do consumers see as distinctive about

brands? Secondly, what do consumers see as distinctive about the advertising of brands?

Thirdly, how do both these questions relate to the visual identity of the brand?

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 23

A total of 467 respondents were interviewed by telephone, across four of the largest states in

Australia. Respondents were randomly selected, with quotas for age, gender and geographic

area. The sample was weighted in analysis according to segment size within the banking

population to ensure a sample was representative of the total banking (consumer) market. We

over sampled Bendigo to reach a threshold. Initially they were asked to identify their main

financial institution. This was followed by a series of open-ended questions where they where

asked to name which, if any, financial institutions stood out and why; which financial

institution had the most distinctive advertising and why; and which, if any, visual elements

helped them identify each brand. For the last question, respondents were given a list of seven

bank brands and asked to respond for each brand. The responses for brand and advertising

distinctiveness were grouped in Excel in terms of similarity where the grouping of responses

was agreed upon by various researchers. For example, responses such as “always on TV”,

“everywhere” and “they have the most ads” were grouped as pervasive.

Results and Discussion

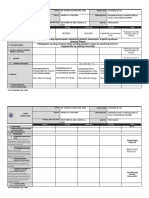

The results for the questions on brand and advertising distinctiveness are shown in Table 1.

The brands are ordered from highest to lowest market share (% of users, column 2).

Table 1: Advertising Versus Brand Distinctiveness (single response)

Brand Usage Brand Advertising

(%) distinctiveness (%) distinctiveness (%)

Commonwealth Bank 26 21 38

Westpac 12 3 3

National Australia Bank 11 6 3

St. George 8 9 13

ANZ 8 5 7

Suncorp 4 2 3

Bendigo Bank 3 11 2

Total 73 58 66

None/Don't know 3 30 26

Other 12 12 6

Total 100 100 100

Table 1 shows that there is no clear pattern between a brand’s market share and the proportion

of respondents who mention that brand as being ‘distinctive’. This holds for both the

distinctiveness of the brand in general (column 3), as well as the distinctiveness of that

brand’s advertising (column 4). For example, Westpac is the second largest brand in terms of

market share. However, it scores second to lowest for brand and advertising distinctiveness.

Likewise, Bendigo Bank, the smallest brand, has extremely high brand distinctiveness for its

market share, suggesting other factors, apart from market share, create distinctiveness.

There is little difference between the average brand distinctiveness (58%) and average

advertising distinctiveness (66%), suggesting that they are both important tools used by the

consumer. The strength of association between the two variables was further explored through

calculating the correlation coefficient between the brand and advertising distinctiveness

mentions, giving a result of r = .294. This value suggests that brand distinctiveness is not

strongly associated with advertising distinctiveness. However, it still indicates a positive

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 24

relationship between the two; meaning brand and advertising distinctiveness are more likely

to both be mentioned for a brand, rather than independently or for different brands. This

result is not surprising, as we could expect that many of the distinctive elements of a brand

would be mirrored in its advertising. Additionally, consumer perceptions are often shaped

through both the brand and its advertising simultaneously (Wansink, 2001). The reasons for

respondents nominating a brand or its advertising as distinctive are examined in Table 2.

Table 2: Results for brand & advertising distinctiveness (multiple response)

Brand Advertising

Feature Distinctiveness (%) Feature Distinctiveness (%)

Distinctive 18 Distinctive 17

Helpful/superior service 10 Pervasive 16

Satisfied customer 10 Taglines 10

Low cost 6 Symbols 5

Community focus 6 Humorous/enjoyable 4

Multiple locations 4 Colours/logos 4

Biggest bank/familiarity 2 Personal service

Longevity 2 appeal 3

Total 58 59

Other 5 Other 9

Don't know/no 1 Don't know 1

particular reason

Total 64 69

The results show that respondents found it hard to articulate just what it was that made a

brand or its advertising distinctive. This is evidenced by 18% (brand) and 17% (advertising)

of respondents saying the brand/advertising was ‘distinctive’ because it was ‘distinctive’.

Further difficulty is evident by the high proportion of respondents saying being a satisfied

customer made the brand distinctive. This is an internal feeling of the customer rather than an

element of the brand. Other characteristics such as the biggest bank/familiarity and multiple

locations are not distinctive but instead relative to their context. Additionally, 16 per cent

mentioned pervasive adverting suggesting, contrary to the literature on distinctiveness, that

sheer volume of advertising can create distinctiveness.

Finally, respondents were asked to name which, if any, visual elements help them identify

with a brand. As mentioned, they were given the list of seven bank brands and asked to

respond for each brand. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Visual Brand Identities for the banking industry (multiple response)

% Who said...

Distinctive feature CBA St. George Westpac ANZ NAB Suncorp Bendigo Total

Symbols 48 80 51 16 28 20 6 249

Colours 57 20 34 56 27 25 24 243

Tagline 16 0 0 3 0 0 0 19

Other 9 7 7 6 7 11 15 62

Total Distinctiveness 129 107 91 81 62 56 45

Nothing 5 4 20 17 28 22 22

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 25

Adverting distinctiveness elements, as opposed to brand distinctiveness elements, came

through more in Table 3. This suggests advertising plays more of a role in forming visual

brand identities than characteristics of the brand itself, at least in the retail service setting.

However, the data does reveal that distinctiveness is associated with external, or

environmental symbols encompassing branch signs and logos.

Of all the distinctive visual features, symbols gained the most associations. Every bank has

their own symbol but some are more successful in identifying a bank than others. For

example, 80% associated the dragon with St. George, 51% associated the ‘W’ with Westpac

and 48% identified Commonwealth’s Bank yellow and black diamond symbol, whereas only

6% associated the letter ‘B’ with Bendigo. Colour was the second most visible element used

by consumers to identify a distinctive bank, but when respondents were asked what makes

advertisements distinctive (Table 2), only 4% mentioned that colours combined with logos

were significant. Taglines were not as mentioned, with Commonwealth and its “Which

Bank?” and ANZ’s “Australia’s leading bank” “Switch now” being the only two banks to

gain mentions on this dimension. However, this result is not surprising as the correlation

between advertising recall and attention, or distinctiveness, has been found to be weak

(Franzen, 1994). Although there is a strong correlation between likeability and recall,

advertising for financial institutions is unlikely to yield a high likeability. However, only

minimum attention is needed for advertising to be effective (Franzen, 1994).

Conclusion

This research has found that brand and advertising distinctiveness exist in the retail service

setting, but that consumers find it very hard to articulate just what it is about a brand or

advertisement that makes it visually distinctive. Distinctiveness is not a function of market

share. But brand and advertising distinctiveness are linked, weakly. Because of these findings,

it might be argued that brand and advertising distinctiveness are not necessarily useful selling

tools. However, the research shows that distinctiveness can convey meaning to the consumer,

such as St. George’s dragon and Commonwealth’s Bank yellow and black diamond symbol,

which helps keep the brand salient. These elements may also reduce wear-out in attention

getting, which in important in the banking industry which consistently advertises throughout

the year.

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 26

References

Agres, S. J., Dubitsky, T. M., 1996. Changing Needs for Brands. Journal of Advertising

Research 36 (1), 21-30.

Birchard, C. W., 1964. Distinctive Advertising for Small Stores. Journal of Retailing 40 (1),

23-31.

Franzen, G., 1994. Advertising Effectiveness. Findings from empirical research. NTC

Publications Limited, United Kingdom.

Franzen, G., 1999. The brand response matrix. Admap (September).

Heath, R., 2000. Low Involvement Processing- a New Model of Brands and Advertising.

International Journal of Advertising, 19 (3), 287-298.

Krishnan, H. S., 1996. Characteristics of Memory Associations: A Consumer-Based

Brand Equity Perspective. International Journal of Research in Marketing 13 (4), 389-

405.

Miller, S., Berry, L., 1998. Brand Salience versus Brand Image: Two Theories of Advertising

Effectiveness. Journal of Advertising Research 38 (5), 77-83.

Olson, C., 2004. Maximizing brand recognition. Information Outlook 8 (1), 43.

Pfahlert, A., Hoek, J., Healey, B., 2004. Brand Colour Associations: A Comparison of Three

Survey Methods. Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy

Conference. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Plasschaert, J., Floet, M. W., 1995. The Meaning of Colour on Packaging. A Methodology

for Qualitative Research Using Semiotic Principles and Computer Image Manipulation.

ESOMAR The World Association of Research Professionals (September).

Playle, S., Hodson, S., 2003. Legal Update. Journal of Brand Management 11 (1), 75-79.

Rex, J., Wai, S., Lobo, A., 2004. An Exploratory Study into the Impact of Colour And

Packaging as Stimuli in the Decision Making Process for a Low Involvement Non-Durable

Product. Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference.

Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Schruntek, W. J., 1999. Looking Up: Brands Stand Out. FoodService Director 12 (6), 34-36.

Simoes, C., Dibb, S., 2001. Rethinking the brand concept: new brand orientation. Corporate

Communications: An International Journal 6 (4), 217-224.

Van de Laar, G., Van de Pas., 2002. Packaging Design: Social Trends and Brand Design.

Admap 429 (June).

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 27

Wanksink, B., Huffman, C., 2001. Revitalising Mature Packaged Goods. Journal of Product

and Brand Management 10 (4), 228-242.

Ward, J. C., Bitner, M. J., John, B., 1992. Measuring the Prototypicality and Meaning of

Retail Environments. Journal of Retailing 68 (2), 194-220.

Warlop, L., Ratneshwar, S., Osselaer, S., 2005. Distinctive brand cues and memory for

product consumption experiences. International Journal of Research in Marketing 22 (1), 27-

44.

Wateridge, S., Donaghey, B., 1998. The endline. important tool or hackneyed device? Admap

November).

ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Branding 28

You might also like

- Begbie, Jeremy Theology, Music and TimeDocument331 pagesBegbie, Jeremy Theology, Music and TimeEdNg100% (1)

- Homosexuality at BYU 1980's Reported in 'Seventh East Press' NewspaperDocument9 pagesHomosexuality at BYU 1980's Reported in 'Seventh East Press' NewspaperPizzaCowNo ratings yet

- Brand Classifications: Identifying The Origins of Brands: Epublications@ScuDocument9 pagesBrand Classifications: Identifying The Origins of Brands: Epublications@ScuHaider QaziNo ratings yet

- Differentiate or Die (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)From EverandDifferentiate or Die (Review and Analysis of Trout and Rivkin's Book)No ratings yet

- Duk-Whang Kim - A History of Religions in KoreaDocument261 pagesDuk-Whang Kim - A History of Religions in Koreaadrianab684100% (2)

- Commit30 - Goal Getting GuideDocument4 pagesCommit30 - Goal Getting GuidePongnateeNo ratings yet

- The Christian in Complete ArmourDocument485 pagesThe Christian in Complete ArmourKen100% (2)

- Impact OF Brand Image and Consumer Perception ON Brand Loyalty: A Study in Context of Patanjali Ayurveda Ltd. Among The People of DehradunDocument36 pagesImpact OF Brand Image and Consumer Perception ON Brand Loyalty: A Study in Context of Patanjali Ayurveda Ltd. Among The People of DehradunSuraj NainwalNo ratings yet

- The Interactive Effects of Colors and Products On Perceptions of Brand Logo AppropriatenessDocument23 pagesThe Interactive Effects of Colors and Products On Perceptions of Brand Logo Appropriatenessalidani92No ratings yet

- Do Logo Redesigns Help or Hurt Your Brand? The Role of Brand CommitmentDocument9 pagesDo Logo Redesigns Help or Hurt Your Brand? The Role of Brand Commitmenthauak jhaoaNo ratings yet

- Brand LoyaltyDocument11 pagesBrand LoyaltyAdina MariaNo ratings yet

- Segmenting Mcdonald'S: A Brand Mapping Approach: Loughborough University Business School, Loughborough, U.KDocument14 pagesSegmenting Mcdonald'S: A Brand Mapping Approach: Loughborough University Business School, Loughborough, U.KabiNo ratings yet

- Impact of Brand Image On Consumers' Purchase Decision: Afrina YasminDocument18 pagesImpact of Brand Image On Consumers' Purchase Decision: Afrina YasminNumra ButtNo ratings yet

- Branding and Packaging Research Published by IqraDocument28 pagesBranding and Packaging Research Published by IqraFalaktaginNo ratings yet

- Article#16Document7 pagesArticle#16Abubaker SaddiqueNo ratings yet

- Literature Review GodrejDocument6 pagesLiterature Review GodrejArchana Kalaiselvan100% (2)

- Nyengerai Et AlDocument8 pagesNyengerai Et AlBusa DhyaneshNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2104451Document16 pagesIJCRT2104451Abinash MNo ratings yet

- Thesis DtuDocument7 pagesThesis Dtuljctxlgld100% (1)

- Brand Name and Consumer's Buying IntentionDocument14 pagesBrand Name and Consumer's Buying IntentionQuynh Mai PhanNo ratings yet

- Mittal, Walsh, Winterich - Do Logo Redesigns Help or Hurt Your Brand The Role of Brand CommitmentDocument10 pagesMittal, Walsh, Winterich - Do Logo Redesigns Help or Hurt Your Brand The Role of Brand CommitmentLana LlNo ratings yet

- LG BrandDocument15 pagesLG BrandKatarina TešićNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Introduction: 1.1. Objectives OF StudyDocument75 pagesChapter 1: Introduction: 1.1. Objectives OF StudyDea Samant83% (6)

- FinalMBRES-3 Grabato 2Document35 pagesFinalMBRES-3 Grabato 2Kc RebadomiaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Brand ImageDocument4 pagesThesis Brand ImageWriteMyPaperInApaFormatCanada100% (2)

- Nafisat Research Paper On MarketingDocument87 pagesNafisat Research Paper On MarketingDavid MichaelsNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Purchasing Behaviour of Male and Female ConsumersDocument42 pagesA Study On The Purchasing Behaviour of Male and Female Consumerskalaivani100% (1)

- Effect of Branding On Consumer Buying BehaviourDocument15 pagesEffect of Branding On Consumer Buying BehaviourRishabh TiwariNo ratings yet

- Impact of Labeling and Packaging On Buying Behavior of Young Consumers WithDocument8 pagesImpact of Labeling and Packaging On Buying Behavior of Young Consumers Withxaxif8265No ratings yet

- Middle European Scientific Bulletin ISSN 2694-9970 Brand Ambassador and Consumer Purchase Decision in Rivers State Godswill Chinedu Chukwu PHDDocument18 pagesMiddle European Scientific Bulletin ISSN 2694-9970 Brand Ambassador and Consumer Purchase Decision in Rivers State Godswill Chinedu Chukwu PHDFitria meleniaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation ProposalDocument20 pagesDissertation ProposalYashvardhan Kochar50% (2)

- Part NovitaDocument8 pagesPart NovitaNovita HariyaniNo ratings yet

- Marketing Intelligence & Planning: Emerald Article: Brand Loyalty in Emerging MarketsDocument12 pagesMarketing Intelligence & Planning: Emerald Article: Brand Loyalty in Emerging MarketsI Putu Eka Arya Wedhana TemajaNo ratings yet

- (325911178) Business Research ProposalDocument12 pages(325911178) Business Research ProposalakshaysvisionNo ratings yet

- Palgrave Macmillan JournalsDocument14 pagesPalgrave Macmillan JournalsLucia DiaconescuNo ratings yet

- Effect of Packaging Design in The PurchaDocument16 pagesEffect of Packaging Design in The PurchazzzzzNo ratings yet

- Secondary Objectives: Objectives of The Study Title of The StudyDocument6 pagesSecondary Objectives: Objectives of The Study Title of The StudyAhamed HussainNo ratings yet

- 10 11648 J Ijdsa 20190504 13Document6 pages10 11648 J Ijdsa 20190504 1328Wiradika Nur FadhillahNo ratings yet

- 011-Icssh 2012-S00010Document6 pages011-Icssh 2012-S00010Asim KhanNo ratings yet

- Consumer Based GloblaDocument20 pagesConsumer Based GloblaBatica MitrovicNo ratings yet

- Brand RecallDocument44 pagesBrand RecallRiddhiman MitraNo ratings yet

- Local vs. Global Brands: Country-of-Origin's Effect On Consumer-Based Brand Equity Among Status-SeekersDocument8 pagesLocal vs. Global Brands: Country-of-Origin's Effect On Consumer-Based Brand Equity Among Status-SeekersRana AleemNo ratings yet

- Learn Branding Through Case StudiesDocument28 pagesLearn Branding Through Case StudiesSadaf ZahraNo ratings yet

- Market ResearchDocument10 pagesMarket ResearchZakky ZamrudiNo ratings yet

- Strong BrandsDocument13 pagesStrong BrandsKarly CaliNo ratings yet

- Impact of Brand Image On Purchasing Decision On Mineral Water Product "Amidis" (Case Study On Bintang Trading Company)Document11 pagesImpact of Brand Image On Purchasing Decision On Mineral Water Product "Amidis" (Case Study On Bintang Trading Company)VictorHubertTambaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Brand Awareness ProjectDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Brand Awareness Projectafmzmqwdglhzex100% (1)

- TranTP Web7 2 PDFDocument14 pagesTranTP Web7 2 PDFShruti AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Brand IdentityDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Brand Identityc5p0cd99100% (1)

- An Exploratory Study of Brand Equity of A Commercial Bank in Vadodara, IndiaDocument14 pagesAn Exploratory Study of Brand Equity of A Commercial Bank in Vadodara, IndiaMaddy BashaNo ratings yet

- The Essentials of Branding - Thinking - LandorDocument11 pagesThe Essentials of Branding - Thinking - LandorInternetian XNo ratings yet

- Brand Awareness V1ycelq5Document26 pagesBrand Awareness V1ycelq5anislaaghaNo ratings yet

- Brand AssociationsDocument11 pagesBrand AssociationsLamine BeddiarNo ratings yet

- Impact of Brand Image On The Clothing Buying Behavior - A Case Study of Marks & SpencerDocument45 pagesImpact of Brand Image On The Clothing Buying Behavior - A Case Study of Marks & SpencerAl Amin100% (3)

- The Influence of Celebrity Endorsement On The Buying Behaviour of The Ghanaian Youth1 PDFDocument16 pagesThe Influence of Celebrity Endorsement On The Buying Behaviour of The Ghanaian Youth1 PDFAnshuman NarangNo ratings yet

- Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services: Fei Zhou, Jian Mou, Qiulai Su, Yen Chun Jim WuDocument10 pagesJournal of Retailing and Consumer Services: Fei Zhou, Jian Mou, Qiulai Su, Yen Chun Jim Wuanis martiaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Corporate Brand Attributes On Attitudinal and Behavioural Consumer LoyaltyDocument12 pagesThe Effects of Corporate Brand Attributes On Attitudinal and Behavioural Consumer LoyaltyjoannakamNo ratings yet

- Consumer Perceptions On Repositioning: A Case Study of VideoconDocument11 pagesConsumer Perceptions On Repositioning: A Case Study of VideoconAzish KhanNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesLiterature ReviewAditya JunejaNo ratings yet

- The Interplay Between Global and Local Brands: A Closer Look at Perceived Brand Globalness and Local IconnessDocument24 pagesThe Interplay Between Global and Local Brands: A Closer Look at Perceived Brand Globalness and Local IconnessRafid RahmanNo ratings yet

- Brand ImpportantDocument9 pagesBrand ImpportantFabian ZárateNo ratings yet

- Dimensions ofDocument21 pagesDimensions ofTomy AhmadNo ratings yet

- Article DOI:10.21474/IJAR01/13274: Journal HomepageDocument6 pagesArticle DOI:10.21474/IJAR01/13274: Journal HomepageIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Social Media Marketing On Brand Equity: A Systematic ReviewDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Social Media Marketing On Brand Equity: A Systematic ReviewPiyushNo ratings yet

- Connective Branding: Building Brand Equity in a Demanding WorldFrom EverandConnective Branding: Building Brand Equity in a Demanding WorldNo ratings yet

- Leadership Lessons From Schools Becoming Data Wise PDFDocument3 pagesLeadership Lessons From Schools Becoming Data Wise PDFrealitymNo ratings yet

- TeacherPlus HTML5 GuideDocument55 pagesTeacherPlus HTML5 GuiderealitymNo ratings yet

- Recommended Readings For AssesmentDocument2 pagesRecommended Readings For AssesmentrealitymNo ratings yet

- Education at A Glance - MexicoDocument11 pagesEducation at A Glance - MexicorealitymNo ratings yet

- Logic GridDocument1 pageLogic GridrealitymNo ratings yet

- To Ad SpecsDocument2 pagesTo Ad SpecsrealitymNo ratings yet

- Global Culture: Beginning Emerging Developing Proficient ScoreDocument4 pagesGlobal Culture: Beginning Emerging Developing Proficient ScorerealitymNo ratings yet

- Demonstration Teaching PlanDocument6 pagesDemonstration Teaching PlanBagwis Maya100% (2)

- Assessment CenterDocument21 pagesAssessment CenterMuradNo ratings yet

- Jack Canfield SuccessDocument49 pagesJack Canfield Successknfzed100% (1)

- 3 Komponen HotsDocument7 pages3 Komponen HotsmeydiawatiNo ratings yet

- Kaisa Koskinen and Outi Paloposki. RetranslationDocument6 pagesKaisa Koskinen and Outi Paloposki. RetranslationMilagros Cardenes0% (1)

- The Duchess of Malfi Essay - Critical Essays: John WebsterDocument10 pagesThe Duchess of Malfi Essay - Critical Essays: John WebstershiivanNo ratings yet

- Planning Aace International: Establishing A Planning CultureDocument1 pagePlanning Aace International: Establishing A Planning CultureSucher EolasNo ratings yet

- Strategy, Castle in TransylvaniaDocument152 pagesStrategy, Castle in TransylvaniaRoberta BaxhoNo ratings yet

- Goethe Elective Affinities TextDocument4 pagesGoethe Elective Affinities TextAaronNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument7 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentRajKamNo ratings yet

- DLL wk6Document36 pagesDLL wk6Cher MariaNo ratings yet

- Employment Outline Short Law 567Document81 pagesEmployment Outline Short Law 567jamesbeaudoinNo ratings yet

- Parable of The Good Shepherd Forerunner CommentaryDocument4 pagesParable of The Good Shepherd Forerunner Commentaryisaac AamagrNo ratings yet

- Slac Eval MayDocument36 pagesSlac Eval MayJMAR ALMAZANNo ratings yet

- Be Unconventional Planner 2022Document92 pagesBe Unconventional Planner 2022GayeGabriel100% (1)

- LORDocument3 pagesLORKuldeep SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Reading DiagnosticDocument4 pagesReading DiagnosticDanika BarkerNo ratings yet

- Lab Report: Rocket Experiment 2017Document20 pagesLab Report: Rocket Experiment 2017api-343596257No ratings yet

- ConjunctionDocument2 pagesConjunctionAngelo Cobacha100% (1)

- Negligence - Breach of Duty: The Reasonable Man TestDocument4 pagesNegligence - Breach of Duty: The Reasonable Man Testnamram1414No ratings yet

- Subtitle Generation Using SphinxDocument59 pagesSubtitle Generation Using SphinxOwusu Ansah Asare Nani0% (1)

- Unconscionability and Standard Form of ContractDocument7 pagesUnconscionability and Standard Form of ContractAravind KumarNo ratings yet

- MythologyDocument9 pagesMythologyrensebastianNo ratings yet

- Gamit NG Wika Sa LipunanDocument5 pagesGamit NG Wika Sa LipunanRamcee Moreno Tolentino0% (1)

- Opinion ParagraphDocument1 pageOpinion Paragraphapi-273326408No ratings yet