Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lindquist - Halbritter Literacy Narrative CCC Feb19

Uploaded by

robert_lestonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lindquist - Halbritter Literacy Narrative CCC Feb19

Uploaded by

robert_lestonCopyright:

Available Formats

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

Julie Lindquist and Bump Halbritter

Documenting and Discovering Learning:

Reimagining the Work of the Literacy Narrative

We suggest that literacy narratives can be an important part of a curriculum de-

signed to encourage students to understand themselves as developing learners and

students. We know that there is great potential for literacy narratives—for narrativiz-

ing—when invited within a scaffolded curriculum of collaborative narrative inquiry.

We place literacy narratives in the service of documenting learning—that is, within

a pedagogical scaffolding designed to lead students through a series of moves that

feature inquiry and discovery (about literacy). As such, the literacy narrative that

emerges as most important is the final reflective narrative: the one we have spent

all semester preparing students to write. That act of deferral creates an opportunity

to put the literacy narrative (LN) assignment to different earlier use as a means for

creating an ongoing, experiential literacy-learning narrative that will be realized

as a reflective narrative: one we call the experiential-learning documentary (ELD).

A scenario: Student X has been eagerly awaiting the return of her Literacy

Memoir assignment. She is worried that she didn’t do well on this assignment

(worth 25 percent of her whole grade!), never having written an essay on the

subject of her literacy, and not even being quite sure what “literacy” means,

C C C 70:3 / february 2019

413

Copyright © 2019 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved.

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 413 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

anyway. It was hard to know how to approach that paper, since her instruc-

tor had told her that lots of things could count as literacy—even things that

didn’t involve reading books or writing papers, or didn’t happen at school.

Trusting that this was true, X wrote about a time when she learned just how

important it was to be a friend, naming the lesson of the experience as one

of “friendship literacy.” Somehow, it didn’t feel to her like this was exactly

what her teacher was looking for, but having been told that she should think

broadly and take chances, she went ahead with the idea—it certainly felt

risky enough.

Finally, her teacher’s response to the work arrives in her inbox. She first

notes the grade of B—disappointing, but not disastrous—and then reads:

Great story, and I’m glad you chose to write about something not usually as-

sociated with school. However, I’m unclear about your definition of literacy.

Also, your essay could use more examples and vivid details (note how Richard

Rodriguez and Amy Tan do this in their essays). Finally, your conclusion needs

more development—lots of people say that loyalty in friendship is important,

but isn’t the situation you’re describing really more complicated than that?

How is knowing how to be a friend a form of literacy?

Not as bad as she feared, not as good as she hoped. She closes the message

and turns to the next writing task, a “research paper.” Maybe this next thing

will go better, X hopes—she really needs to bring up her average, if she is to

be admitted to the major. This time, she’ll be sure not to take any chances

with the assignment—this one didn’t pay off so well, and she believes that her

high school English classes have, at least, taught her some less risky strategies

for earning good grades on her writing.

We begin with a twofold premise: that literacy narratives can be an impor-

tant part of a curriculum designed to encourage students to understand

themselves as developing learners, and that the affordances of literacy

narratives as learning experiences within writing curricula have yet to be

fully realized. As Johanna Schmertz observes in her review of a recently

published study of students’ narratives, “in the fields of literacy and com-

position studies, the idea that story and performance create who we are is

assumed more than it is articulated or explored,” even as we maintain “a

longstanding belief in the importance of literacy narratives as pedagogical

classroom tools.” Per Schmertz’s observation, it seems to us that much of the

414

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 414 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

discussion about literacy narratives rests on a ground of commonplaces that

may sometimes occlude further inquiry into the practices they promote.

So it goes with commonplaces.

Our work here is not to condemn such commonplaces—which have

emerged as products of disciplinary formations for historical reasons that

are beyond the scope of our discussion—but rather, to expose how we

stumbled upon, by way of a somewhat improbable association, the exigency

for an inquiry into commonplaces of teaching literacy narratives. As writing

teachers who, like many others, imagined that we may be better able to teach

our students if we only we knew more about them as learners, we designed

and conducted a research project, LiteracyCorps Michigan (LCM), intended

to be a vehicle for this discovery (see Halbritter and Lindquist, “Time”).1

In the service of that research project, a long-term inquiry into forms of

literacy sponsorship in the lives of undergraduate writers, we discovered

something of equal (or perhaps greater) value than the more immediate

answers we sought: we learned that students’ stories can function not only

as texts of their learning but as texts for their learning—that their stories,

once told, were most valuable as resources for their ongoing storytelling, not

merely as examples of their storytelling, per se. So it goes with storytelling.

To be clear, our goal here is not to provide an elaborated report on our

LCM research, per “Time, Lives, and Videotape.” Rather, it is a recommen-

dation for a program of pedagogical interventions derived from our ongo-

ing thinking about methodology—a theoretical system governing applied

research methods—that has greatly shaped our pedagogy—a theoretical

system governing applied teaching methods. One result of this methodologi-

cal thinking developed through the LCM project is that we began to look

carefully at how we were using literacy narratives both in our research and

in our teaching practice. And that made us ask, why had we been treating

so differently the literacy-related stories students produced in these two

different-but-related contexts? So we treated that as a real question. So it

goes with teacher-researchers.

Here we describe the foundations and moves of our resulting pedagogy:

one that situates the literacy narrative (LN) within a series of storytelling oc-

casions in the service of emerging and ongoing stories of students’ learning

selves. To describe what such an approach might offer and entail, we con-

sider current treatments of the LN as a curricular piece in first-year writing

(FYW) and recommend reimagining the work of this piece, repositioning it

415

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 415 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

to participate in a series of scaffolded (iterative) pedagogical events. What

we are suggesting is that the LN, as a literacy experience, might (contra the

situation described in the above scenario) be conceived as the beginning,

rather than the project-bound culmination, of a generative storying process.

In what follows, we discuss how narrative inquiry has been useful for us

in situating LNs within a pedagogical practice—a move prompted by our

consideration of the theoretical and methodological affordances of narra-

tive inquiry in LCM. Again, we invoke the study and its methodology here,

not to report on the specific questions that LCM helped us address, but to

pursue one of the many questions with which we were left as we reflected on

what we had learned.2 As teachers of FYW, we were left wondering how we

could transfer what we had experienced in LCM into the FYW classroom.

How could our long-term narrative inquiry methodology for a process of

discovery—one that develops over several years—inform one that develops

over the span of fifteen weeks?

We suggest that LNs composed by students might participate in a ped-

agogical approach characterized by attention to time, emergence, emphasis

on narrative performance as social practice, and informed reflection.3 Such

a pedagogy extends the possibilities of approaches that treat LNs primarily

(1) as a means for assessing literacy histories in order to discern and correct

values associated with literacy and schooling, and (2) as performances of

autobiographical genres (and therefore as occasions for learning mastery

of the conventions of formal narrative genres: e.g., “the personal essay” or

“the memoir”). By contrast, we offer a pedagogy that operates by way of a

methodology for students to discover things about their own learning by way

of a system of informed reflection. In this way, we treat narratives, insofar

as they participate in a program of narrativizing, both as a practice that

enables learning as a change in one’s orientation to the affordances of one’s

experience, as well as a move that works in conjunction with opportunities

for deliberately scaffolded informed reflection. We follow from the work of

others (see, for example, Bean; Mack; Mahala and Swilky; Robillard) who

have called for narrative invention in writing classes, and develop the claim

that narrative intervention is important to this goal. We have come to believe

(from our experiences as teachers, as well as from our LCM research) that

strategic narrative interventions are important to what students stand to

learn from composing LNs.

416

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 416 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

We find that these interventions can operate most effectively within

a framework of pedagogical values and practices in which writing is posi-

tioned as a means of learning, rather than as the goal of learning—in other

words, in the context of a curriculum in which writing is used as a means

for facilitating, identifying, and articulating learning goals throughout a

sequence of scaffolded writing moves. In the pursuit of these learning goals,

students learn to become more purposeful and effective writers—even if,

and especially because, writing (as a performance of genre) is not directly

taught and assessed as such. Such a shift in value and emphasis gives us

the necessary space to more fully realize the affordances of narrative (as a

type of discourse) and narrativizing (as a practice related to storytelling)

for reflection and learning.

With this as our goal, we (1) situate our discussion within ongoing

conversations about the pedagogical uses of LNs, (2) consider relation-

ships of narrative to learning and reflection, (3) describe the operations

of the LCM research project that has served us as a model for the kinds

of curricular moves we are proposing, and (4) discuss the role of iterative,

informed reflection (and in particular, of a forecasting/projecting move

we have named preflection4) in making good on the inventive potential of

learning narratives as storytelling experiences.

As the title of this piece suggests, the following discussion places LNs in

the service of documenting and discovering learning—that is, within a peda-

gogical scaffolding designed to lead students through a structured series of

moves that feature inquiry and discovery. As such, the LN that emerges as

most important is the final reflective narrative: the one that we have spent

all semester preparing students to write. That act of deferral creates an

opportunity to put the LN assignment to different earlier use as a means

for creating an ongoing, experiential literacy-learning narrative that will be

realized as a reflective narrative: “the experiential-learning documentary”

(ELD), as we have come to name it (Halbritter and Lindquist, “It’s Never”).

And because we want to have as much time as possible to create learning

interventions between the LN and the ELD, we recommend placing the

LN early in the assignment sequence. We direct our attention toward the

scaffolding of the learning opportunities, the sequencing of the assign-

ments, and the documenting of the students’ experiences in the course.

Consequently, our discussion relies less on theories of composition (how to

get students to write well), per se, and more on narrative theory (the sorts

417

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 417 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

of learning narrative events and practices they occasion) and theories of

experiential learning (how to engineer experiences that favor learning and

the documenting of learning). In short, we look less at the LN as a source

of pedagogical promise in and of itself (i.e., what it is), and concentrate on

how we may better utilize LNs in our teaching (i.e., what we do with them).

The Literacy Narrative as an Instrument of Transition

In FYW classes, assigning LNs as an introductory experience has become

a common curricular move: a glance at popular composition textbooks,

writing programs, and conference programs from professional meetings

(e.g., CCCC, NCTE) reveals that the practice of assigning personal essays

about literacy experiences is pervasive. Sally Chandler points to an expand-

ing body of research directed to the study of LNs, counting (as of 2013) 218

dissertations featuring LNs, 136 of which had been produced since 2008.

But the ongoing disciplinary fascination with LNs has yet to be fully

expressed in a program of inquiry into what it means to invite, support,

and learn from these stories as inventive practices (following, for example,

the work of Chandler; see also Scott and Robillard, whose articles were

published in 1997 and 2003, respectively). A good place to begin in moving

toward such an inquiry is to ask, What are the rhetorical and pedagogical

reasons motivating why LNs—first-person writing projects designed to

invite students to reflect on their experiences with learning and/or read-

ing and writing—are typically assigned? From what we have been able to

discern from the available literature on uses of LNs, it appears that they

are assigned in order to accomplish the following:

• Facilitate transition to college writing. LNs are thought to offer

writing experiences that invite less traumatic transitions to college

writing, enabling first-year college students to begin writing using a

familiar rhetorical practice (narrativizing), one that makes good on

the already-available materials of prior experience.

• Encourage students to reflect on educational goals. LNs are believed

to encourage students to do the critical and self-inventive work of

thinking about how their past lives as students and members of

communities map onto their present and future lives as students

and citizens; and

418

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 418 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

• Diagnose students’ learning needs. LNs are assumed to be educa-

tional for teachers as well as students (that teachers, in reading

such tales, may learn things about their students’ educational expe-

riences that will prove useful for teaching the moves and expecta-

tions of academic literacy).

Susan DeRosa’s work, “Literacy Narratives as Genres of Possibility,” stands

as an example of one line of thinking about the pedagogical uses of LNs.

DeRosa explains that by telling reflective stories about “literacy practices,”

students stand to (1) identify and reflect on their roles and responsibilities

as writers—a sense of ethos, (2) develop an understanding of their literacy

in flux and a sense of agency as writers, and (3) develop awareness of their

“literacy in action” (2). J. Blake Scott, similarly, writes that “literacy narra-

tives can help validate students as authors and writers (112). Mary Soliday

speaks to the potential of LNs to enable students to think more deeply

about the difficulties and stakes of communication in relation to power:

“Reading and writing literacy stories,” she explains, “can enable students

to ponder the conflicts attendant upon crossing language worlds and to

reflect upon the choices that speakers of minority languages and dialects

must make” (512).

From Narratives as Genres to Narrativizing as a Practice

The teaching of literacy doesn’t have to end once students turn in their nar-

ratives. . . . [T]hus, the literacy narrative is a starting point for further inter-

rogation and reflection. (Scott 110)

We find that much of the disciplinary thinking about the uses of LNs in

FYW curricula retains a focus on the genre-specific features of LNs as texts

(whether produced by published writers or by writing students), rather

than as practices (Scott’s work is an exception, arguing that production,

rather than consumption, of LNs should be a primary goal). In “Successes,

Victims, and Prodigies: ‘Master’ and ‘Little’ Cultural Narratives in the

Literacy Narrative Genre,” for example, Kara Poe Alexander makes a case

for a broader understanding of the contents of LNs produced by students

in first-year writing classes. She describes LNs composed by students as

making predictable thematic moves and observes that these moves often

419

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 419 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

express conventional tropes of achievement and mobility. To contextual-

ize her findings about these themes, Alexander cites scholarship that finds

students’ LNs “follow conventional patterns of narration and correspond

to prevailing cultural representations of literacy perpetuated through

literature, film, television and the news media” (609). Alexander wants to

complicate this picture of correspondence between master narratives of

literacy and success and to identify the “little narratives” that show up in

students’ writing about their literacy experiences. She is concerned that

students’ stories of literacy are problematically co-opted by powerful cul-

tural discourses about relationships of literacy to power and mobility; she

writes, “It does seem, however, that students rarely explore the possibility

that the literacy-equals-success narrative is a faulty or, at the least, an overly

generalized myth, even though many scholars have noted this point” (610).

While Alexander’s study offers a useful picture of what students pro-

duce when they are asked to create LNs, we see her work (also) as a useful

articulation of the disciplinary exigency for the move toward narrative peda-

gogy we recommend. In the end, Alexander advocates bringing students to

better practice—correcting their understandings of how literacy operates in

the world. Alexander concludes from her study of students’ “little narratives”

that “literacy is intricately connected to identity”—an assertion with which

we wholeheartedly agree. We would, however, suggest that the relationship

between literacy and identity, as it is performed in students’ narratives, is

the place to begin imagining the kind of pedagogical work such narratives

can do in scenes of writing instruction. That is, we recommend deferring

the impulse for immediate intervention in these first narratives to ensure

that students get their stories right, in favor of listening for what they might

reveal about, and function within, students’ literate lives—in other words,

to preserve what students may not be getting right in their early drafts in

order for students, themselves, to discover their earlier shortcomings upon

later reflection following subsequent writing experiences.

To use a metaphor from moviemaking, it may be helpful to think of

the first LN that students create as a kind of “establishing shot” that sets

the scene for further action. In moviemaking, an important scene-setting

move is the establishing shot: a wide view of the location where the action

of the scene will take place. For example, sitcoms often open with a shot of

the city and then a shot of the house or building where much of the primary

interaction between characters will take place—often a single room in an

420

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 420 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

apartment or house (actually a sound stage in North Hollywood). Ken-

neth Burke suggests that “scene is a fit ‘container’ for the act, expressing

in fixed properties the same quality that the action expresses in terms of

development” (3). The establishing shot, then, not only situates viewers in

the larger world; it suggests a host of likely possibilities and improbabilities

for appropriate action and interaction that the immediate scene cannot

reveal—whether or not those possibilities or improbabilities are immedi-

ately relevant to the specific scene.

We suggest that rather than critiquing students’ LNs as finished,

nuanced, and complicated articulations of literate lives, we treat these

narratives instead as establishing shots—as overviews of a host of likely

possibilities and improbabilities for appropriate action and interaction that

the immediate scene of learning cannot reveal—for the evolving under-

standings that the full course is designed to deliver. As establishing shots,

LNs give us a big-picture view of the sort of action that will likely unfold:

that is, they set the scene for the ongoing work of pursuing the ELD. And,

as establishing shots, we can always return to them, later, to see if our pre-

dictions were warranted or if they have somehow been changed by way of

the ensuing action. When we look again, we may find that the establishing

shot did suggest appropriate action that we simply overlooked or were not

yet prepared to notice upon first glance.

LNs can help establish the scenes of learning for each and every stu-

dent. As such, the LN may be employed to perform (even more) productive

kinds of diagnostic work. As we explain, these pedagogical moves were

derived from the methodology of LCM, our long-term literacy research

project that puts LNs, generated in scenes of research interviews, at the

center of its inquiry. From this, we have evidence to suggest that LNs—as

inventive acts and rhetorical performances—can do important work for

students and teachers, but that such work must be supported by purpose-

ful curricular interventions. Positioned in this way, LNs participate in a

pedagogy of following, rather than in a pedagogy of genre modeling. The LN

then becomes, as Scott puts it, “a starting point for further interrogation

and reflection” (111).

Documenting What We Don’t Yet Know

Further, we believe that because such an approach does a better job of mak-

ing good on the heuristic potential of experiences relevant to learning (that

421

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 421 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

is, potentially any experience), it can be a path to access for diverse learn-

ers. Researchers and scholars concerned with supporting nonmainstream

students have recognized the need for richer, more nuanced understand-

ings of how narratives can work pedagogically. We think, for example, of

Amy E. Robillard, who, in responding to the ongoing need to create more

accessible learning opportunities for working-class students, has called

for “a more complex pedagogy of narrative,” one that would “pay more at-

tention to how our students write their stories, why they write them, and

how they conceive of time in those stories” (91). Robillard sees personal

narrative writing as a means for working-class students to manage predica-

ments of studenthood by marshaling, and learning how to understand, the

affordances of their past experiences. She makes the case that the practice

of narrativizing is important for working-class students in particular, not

only because first-generation college students are already experienced in

practices of narrativizing, but also because they may not have histories of

projecting futures in ways that have been carefully planned and supported

by their social environments.

Our inspiration for rethinking the role of LNs, our LCM project, put

us into a different relationship as learners with students and their stories—

different, that is, from what is typically possible in the time and space of a

writing classroom (Halbritter and Lindquist “Time”). Listening to students’

LNs in alternative learning environments—along a much longer timeline,

and in spaces other than the classroom—made available to us new under-

standings of what facilitated processes of narrativizing can do for students.

The expanded timeline of LCM allowed us to make some observations

about how stories develop in narrative encounters, how to facilitate this

process, and how we might position ourselves as learners-from, rather than

solely as teachers-of, students’ stories. And this has changed how we see

the affordances of such stories within the greatly abbreviated timelines of

our FYW courses.

LCM was originally motivated by our desire to learn more about the

futures that first-generation students projected by way of their experi-

ences in higher education (Halbritter and Lindquist “Time”). Our goal of

investigating literacy sponsorship in students’ lives was served by eliciting

LNs from participants in scenes of collaborative invention (e.g., video-

recorded interviews). As such, we discovered that they had to be carefully

supported and scaffolded as inventive acts (to be made available for future,

422

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 422 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

iterative acts of reflection). The LCM project is what helped us imagine

how we might position the LN as a rhetorical process within a more fully

developed narrative pedagogy, an approach to teaching and learning that

life history researchers Ivor F. Goodson and Scherto R. Gill describe as “the

facilitation of an educative journey through which learning takes place

in profound encounters, and by engaging in meaning-making and deep

dialogue and exchange” (123). In such a pedagogy—as in our methodology

for LCM—narratives of self are both the enactment of inventive acts and

the exigency for the responsive narrative acts that follow. Another way of

saying this is that these encounters are exploratory drafts—they are most

certainly not final.5 Recognizing this, we developed a pedagogy that would

allow us to continue drafting with students—one that leveraged a method-

ology that could enable our students to document their evolving educative

journeys. Research and scholarship in narrative inquiry and, in particular,

life history—traditions of inquiry organized by questions such as How do

narratives work? What occasions them? and How can we understand how

they operate?—became useful to us first as researchers and now as teach-

ers, in thinking about the kinds of social and rhetorical work that stories

of life experience can do (see, for example, Bruner, Acts, Making; Clandenin

and Connolly; Goodson and Gill; Grumet; Gunn; Schleiffer and Vanatta;

Thomson). As we suggest above, ours is a pedagogy that operates by way

of a methodology for students to discover things about their own learning

within of a system of informed reflection.

We are encouraged, at least, to see that current thinking about the

functions of personal narratives in the development of student writers has

moved away from the idea that such writing is valuable primarily because

it allows for an authentic expression of self-realization. Scott, for example,

explains that when he teaches LNs, he is “less concerned with the authentic-

ity of the stories students tell than with the fact that they see these stories

as worth telling” (109). Yet it seems that pedagogical practices using LNs

often work from the idea that narratives do predictable kinds of things

for their creators and audiences, and that the scenes in which they are

produced are not significant to their content or function. There is (always)

more to learn about how these acts of storytelling function, and how their

functions might be variable and contingent upon the conditions of their

telling. Consider, for example, DeRosa’s defense of LNs against Jane Greer’s

critique of them as performative acts that can be complicit with oppressive

423

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 423 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

practices of schooling. DeRosa worries that critics such as Greer “often label

literacy narratives as ‘conversion narratives,’ and are skeptical of the ‘success

stories’ produced in students’ literacy narratives,” citing Greer’s concerns

that “conversion rhetoric in students’ narratives often aims at pleasing the

instructor,”6 and that “asking students to write specifically about cultural

literacy issues is itself a form of exclusion of students’ voices, a repressive

pedagogical practice similar to those that students have encountered in

their past schooling experience” (5). DeRosa suggests that “[i]t seems hasty

on the parts of critics who imply students’ reflections on their literacy ex-

periences lead them to become mired in a particular historical narrative

or force them to adopt a potentially repressive discourse,” on the grounds

that such criticisms risk a too-hasty dismissal of narrative pedagogy and

its potential for meaningful reflection (5).

We further suggest that it is essential to understand LNs as perfor-

mances that take place in scenes defined by histories, relationships, and ma-

terial environments—and that it is (precisely) the inevitable performativity

of storytelling that gives it much of its generative force as a pedagogical

practice. That students (behaving in their capacity as people) tell particular

stories, within specified contexts, for certain purposes is an understanding

that should be central to any pedagogy that puts LNs at the center. What

we are suggesting is that the production of LNs should be positioned early

in the writing curriculum, and that the instruction that follows should be

directed to revealing the situated nature of stories of literacy—stories with

which students may continue to enter into dialogue over the course of the

term as they are referenced in students’ ELDs.

And while the production of LNs is important as a situated act of

literacy in and of itself, the product that narrativizing yields is critical to

facilitate each writer’s ongoing dialogue over time. By way of these early

LNs, students may enter into dialogue with their former selves in order to

discover ideas about literacy that have changed by way of their subsequent

studies and literate practices.7 In this way, the early LNs serve as data for

later reflection; that is, whereas the LN is supported by each student’s

memories, the later reflection will be supported by the elements present

in the LN, students’ experiences of subsequent writing activities, as well

as the resources created by way of those activities. Thus, the early use of

LNs serves to represent each student’s starting point in terms of not only

familiarity (or lack thereof) with literacy as a theoretical topic or set of

424

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 424 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

practices, but also in terms of each student’s approach to storytelling more

generally: using examples to support claims in the storytelling, accessing

and employing vocabulary and grammatical structures, and a host of other

writerly concerns.

Consequently, we recommend “collect it, don’t correct it,” when it

comes to the early LN. Rather than revising with the goal of improving

students’ LNs, our students will study their LNs periodically throughout

the semester to see how their initial LNs square with the ensuing learning

experiences of the course. And while we will certainly attend to the craft of

each piece of writing our students do, our mission in inviting students to

produce this early story is to create an occasion for further acts of storying.

That is, rather than undergo subsequent revision, the earlier story will be

available to inform subsequent re-storying by later versions of students’

selves. It should be noted that this use of the LN is significantly different

from its treatment in a portfolio approach, in which the point is often to

revise the original LN to reflect the student’s new-and-improved skills and

sensibilities. Rather, this approach archives the first LN, not for revision, but

for subsequent inquiry. This early LN may make evident a version of the

student—a former self—who had not yet learned something: the implica-

tions of no longer defensible positions, organizational strategies that had

not yet emerged, ethical understandings that had not yet been articulated,

nascent ideas that had not yet been developed or realized, and so forth.

Finding Literacy Narratives in Pedagogic Encounters

The student must see everything for himself, compare and compare, and always

respond to a three-part question: what do you see? what do you think about it?

what do you make of it? And so on, to infinity. But that infinity is no longer the

master’s secret; it is the student’s journey. (Rancière 23)

“[N]ot all literacy narratives are created equal when it comes to the work they

do for students and what they communicate to teachers. For some students,

creating a literacy narrative may be their first opportunity to invent a self with

an educational history. For others, it may present yet another opportunity to

refine fictions drafted long ago of who they are as good students. The work in

one case might entail facilitating the process of creating a useful narrative of

their studenthood; in another, it might be more deconstructive, getting students

to understand how developed narratives have served them and what might

happen if they understood differently the experiences and events their narrative

renders. (Lindquist 180–81)

425

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 425 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

In her work facilitating LNs with students in an urban university, Chandler

cites the work of narrative researchers such as Michael Bamberg and Al-

exandra Georgeakopoulos in pointing out that stories can serve different

functions—and therefore emerge differently, formally, and over time—for

tellers, depending on their proximity to mainstream experiences and the

conventional narratives associated with these experiences. Chandler notes

that “experiences or beliefs that cannot be easily prepackaged in main-

stream cultural stories are often signaled by abrupt changes in subjects,

digressions, hesitations, contradictions, repetitions,” and she goes on to say

that “‘unstories’ often stop and start, or end up being told as collaborative,

interactive conversations—rather than as intact, coherent stories” (29). The

LNs of students whose identities are rendered via “unstories,” then, may not

be immediately recognizable as stories of identity because (in the words of

Chandler) “they don’t present features of the mainstream identities that

define what stories are” (30).

The LCM project works from these fundamental values and as-

sumptions about the rhetorical potential of narrative acts (Halbritter and

Lindquist, “Time”). This research, which develops in distinct stages, invites

and facilitates narratives that are co-constructed over time. In our first

interview with students, we ask them to bring artifacts not only because

the exploratory work of that phase demands that inquiries follow (and do

not lead) participants’ stories, but also because we want to give students

permission (or encouragement, as the case may be) not to have to deliver an

expected narrative of schooling (“I always hated school” or “ I was always

an A student”)—or, at least, to defer this interpretive closure in favor of

less obviously goal-directed, exploratory stories. We want interviews to do

both constructive work (moving toward coherence) and deconstructive

work (moving toward reflection)—depending on the needs of particular

students. This move is intentionally scaffolded in the design of the research,

but it still can’t predict how students will take up the initial invitation to tell

us stories. Some will try to find a way to tell the story they want to tell to

adults in an educational institution; others will not attempt to deliver this

particular performance. We have found that some students, for example,

offer constellations of stories that have their own forms of coherence, but

that do not, at least early on, seem recognizable as LNs. Others, however,

understand the scene of telling—in which they are speaking to an audi-

ence of teacher-researchers in an institutional setting—as an occasion to

426

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 426 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

deliver a highly mediated narrative of studenthood, reading and writing

proficiency, and achievement.

In listening to such students, we understood, as researchers, that

if we wished to learn less readily available things about the people and

places that are the literacy sponsors in their lives, we would have to create

opportunities for students to reflect, and that this would take both careful

relationship building and time. In short, we collected these stories—we did

not correct them, as there is essentially nothing about them that can be

wrong. We did not, for example, ask LCM participants to re-create improved

versions of our earlier conversations (as though that could be possible—or

even if it were, that it could somehow be desirable). We saw the value of

LCM participants’ early stories as attached to what they gave us to work

with; that is, their capacity to inform “further interrogation and reflec-

tion.” Similarly, as teachers, we suspect that we stand to learn more about

students’ literate lives from those stories that are less carefully mediated,

as stories of literacy and education. As researchers, we didn’t simply collect

these stories in acts of conversation: we collected these stories by way of

multicamera, video recordings that allowed us not only to play back what

participants have said but also to reconstruct the conversation by shifting

perspectives by way of varying camera locations. These video renderings

of our former conversations conducted by our former selves represented

shared texts from which we could re-story: get more information, extend

facets of the former conversation, and identify things that we are learning

by way of our recorded conversations.

As teachers, we have learned that we got lucky in the scaffolding of the

LCM project. While we suspected that our research would yield new under-

standings of students’ lives and aspirations, we would not have predicted

that the project as we approached it initially would have taught us so much:

not only about what we needed to learn about students’ literate lives, but

also about how we should be thinking about designing and approaching our

FYW curriculum. For while our first encounter with students as research

participants indeed sets up relationship building and future acts of reflec-

tion, it critically models the overall mission of the project: to connect past,

present, and future versions of “self ” by way of literate acts (Halbritter and

Lindquist “Time”). In other words, the moves of the first (phase one) inter-

view comprise the establishing shot of the project: they set the larger scene

and “express in fixed properties the same quality that the action expresses

427

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 427 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

in terms of development” (Burke 3). In so doing, they suggest appropriate

acts within this scene of reflection even as they, by way of the video record,

document a version of the self that we will later ask the narrator to return

to and engage in dialogue. This personal narrative will emerge as evidence

for a later LN—one based upon the evidence we generate, not merely one

we craft from our memories of these initial conversations.

James Holstein and Jaber Gubrium remind us that “viewing stories of

personal experience as a matter of practice allows us to expand this concern

to ask questions about who is, or is not, entitled, obligated, or invited to

offer their stories and under which institutional, historical, and material

circumstances” (179). We have learned via the LCM project interviews that

invitations to narrators to document important people and places in their

lives can offer them spaces for invention otherwise unavailable to them. In

fact, the matter of who seeks out the opportunities for invention the LCM

project can provide—that is, which students imagine participation in the

project to offer them useful spaces for self-authorship and invention of new

narratives of literate lives—itself functions, in concert with the stories told

and offered, as an indicator of educational history and forms of sponsor-

ship. Consider the predicament of first-generation students hard-pressed

to render meaningful accounts of their experiences of studenthood to

audiences in their home communities lacking the contexts to help make

meaning of these accounts—or, for that matter, to teacherly audiences, in

which the stakes of telling the wrong story are unpredictably and scarily

high. Consider, too, eighteen-year-olds who have just exited a public school

system that seldom utilized their own experiences—much less their first-

person accounts of them—as resources for their learning. LCM appeared

to serve as an opportunity for such students to claim space within their

own learning journeys.

We came to see that how students regard and treat interviews as

spaces for invention is one indicator of the forms of sponsorship they have

experienced in their lives so far. One of the first students with whom we

worked, a young woman from Flint named Liberty Bell, had been regarded

by others in her home community as the local success story, as the one who

was destined to “go places”—at the same time she was struggling against

teachers’ perceptions of her as underprepared. For Liberty, the opportunity

to tell her story to interested adults, to reflect on her experiences and project

her story into the future, was something she perceived as doing important

428

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 428 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

inventive work for her in a space that otherwise did not exist in her life. In

other words, when students such as Liberty Bell agree to participate in the

LCM project and come to regard the project as a kind of literacy sponsor

otherwise unavailable, this, too, can open insights into literacy histories

and patterns of sponsorship (Halbritter and Lindquist “Time,” “Sleight”8).

We are reminded of Annette Lareau’s study of the educational ex-

periences of children from working- and middle-class communities. In

that study, Lareau remarks on the striking differences in entitlement to

intervene in the conduct and decision-making processes of school insti-

tutions between working- and middle-class families. In Lareau’s observa-

tions, middle-class parents were much more likely to assume that their

own stories of their children’s needs and capabilities would be welcomed

and sanctioned by educational institutions and to expect results based on

these (tactically deployed) stories. Working-class parents, by contrast, did

not feel authorized to offer such stories as strategic interventions in their

children’s schooling. Such beliefs about where and when stories of self are

appropriate in educational settings are themselves expressions of literacy

histories. Our realization that LNs do far more complicated forms of work

than we had imagined has convinced us that they deserve both fully theo-

rized research methodologies and pedagogies to realize their possibilities.

DeRosa asks her students to write a series of LNs: “several self-reflective

literacy narratives that accompany each of the genre-based writing projects

for the course” (3). This seems like an appropriate move—far more genera-

tive than the single literacy-story performance that curricula typically invite.

What we would like to offer in an effort to make DeRosa’s approach even

more productive is a set of scaffolded curricular moves that make good on

the inventive potential of LNs we have discovered though our LCM research.

The Preflective Curriculum and the Values That Direct and

Assess Our Efforts

In all cases, it is a question of observing, comparing, and combining, of making

and noticing how one has done it. What is possible is reflection: that return to

oneself that is not pure contemplation but rather an unconditional attention

to one’s intellectual acts, to the route they follow and to the possibility of always

moving forward by bringing to bear the same intelligence on the conquest of

new territories. (Rancière 36–37)

429

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 429 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

In our opening scenario, a student is given a literacy narrative assignment.

In this scenario, Student X is given a task for which she is assessed from

evidence of her ability to execute certain moves: (1) an ability to craft an

essay that shares rhetorical characteristics of published stories of literacy;

and (2) an ability to “think critically” about literacy; that is, to make an

implicit claim about the nature of literacy that demonstrates skepticism

about popular commonplaces. The resulting essay about Student X’s lit-

eracy experiences becomes a written product to be assessed in the same

way, and for similar purposes, as other written artifacts she may be asked

to produce in the course of her first-year writing experience. Though the

LN may have been diagnostically useful in helping her understand that she

may be inhabiting a new domain of discursive practice and value (literacy

isn’t just reading and writing!), and in helping her teacher learn some things

about her out-of-school experiences prior to college (the better to make

some inferences about her educational needs and priorities), the inven-

tive work the student has done in telling the story will have no formal or

intentional future use for helping her continue to understand her educa-

tional project and in helping her make good on the lessons of experiences

that may otherwise be unavailable for consideration in this regard (unless,

that is, her LN is part of a portfolio—in which case, she may be asked to

go back and write a better, updated version of it). It will likely do little to

convince her of the epistemic value of writing or of the integral role that

the project of narrativizing will come to play in the unfolding projects of

the semester to follow.

Let’s take a moment to consider the difficulty of the task that this

kind of assignment presents to Student X and her peers: students are being

asked to reconsider their memories by way of a theoretical lens that they did

not have, let alone use, when making those memories and that they do not

yet control. John Dewey writes about the “tendency” of teachers to justify

the value of their curricula by virtue of “miraculous potencies . . . powers

inherently residing in the subject, whether they operate or not. . . . If they

do not operate, the blame is put not on the subject as taught, but on the

indifference and recalcitrancy of pupils” (245). Is it any wonder (as Greer

has observed) that the results of such an assignment tend to be less than

satisfying? Is it any wonder why such an approach may lead to blaming the

indifference and recalcitrancy of the students when the powers inherently

residing in the subject fail to operate?

430

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 430 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

We wonder: how has it taken us so long to shift the blame to the

subject as taught?

The answer to this question, we suspect, is a complicated one, having to

do with disciplinary histories and formations, values and aspirations, com-

monplaces of theory and practice. That is a robust and necessary direction

for future inquiry. For now, however, let’s imagine an alternative scenario

in which our Student X is assigned a literacy narrative early in the course.

She is given only a few days to complete the project, since the product,

while it will be generative for what follows, will not be evaluated primarily

for indicators of good performance. It will, instead, become the subject of

ongoing reflection and the starting place for developing a narrative about

how her experiences prior to this moment have delivered resources that

can be repositioned (or understood) as assets for the purposes of meeting

her educational goals. In that narrative, student X may (or may not) arrive

at conclusions that strike her teachers as performances of commonplaces

about literacy, social mobility, and achievement. She, along with her peers,

will be invited to revisit these conclusions through a series of narrative

interventions (for example, peer reviews, interviews, and reflections fol-

lowing subsequent writing assignments) and by way of a reflective activity

both immediately following the exercise and at the end of the course. In

this scenario the LN is positioned not only as a reflection on the past but

also as a projection (that is to say, a preflection) for the future.

Of course, shifting the role of the LN assignment involves more than

simply collecting and (not) correcting—far more, in fact. In order to avoid

the trap of relying on miraculous powers inherently residing in the subject,

we will need to do some preflecting of our own prior to assigning the LN.

Most important will be to imagine what types of claims we most want our

students to make in their final reflective narratives of the semester (e.g., I

learned how to manage evidence in my writing, I learned how to take ad-

vice from peers, I learned my first drafts rarely include an explicit thesis, I

learned how to create and follow a schedule for drafting responses, I learned

I’m terrible at proofreading) and to begin engineering opportunities for

students to generate evidence that will enable them to discover such claims

in the eventual archive of their work. Consequently, the scoring rubric for

the early LN assignment may look more like a shopping list than it does a

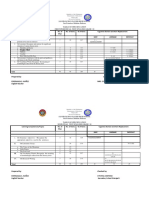

holistic, qualitative scoring rubric (see Figure 1).

431

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 431 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

Figure 1. Assessment form for the LN.

With our revised mission of supplying evidence for future reflective

activities, we will need to ask students to tell stories about what they know,

how they believe they have come to know it, and how this knowledge shapes

other things they do. Some of the stories that emerge from such a prompt

will be outstanding stories in and of themselves. Others, perhaps, not so

much. However, stories that fall at any point along the qualitative spectrum

will be useful if they yield claims about learning, about what is important,

about the writers’ expectations, or about ways they have acted based upon

their knowledge. In fact, if the point of the course is to get students to

manage evidence or examples ethically and to discover claims by way of

evidence or examples, then even evidence-free LNs (“I read everything I get

my hands on. I love to read and write. Reading and writing is the best ever!”)

may emerge as productive later when students may cite them as evidence

or examples of their development. However, they will be able to do so only

if we attend to generating and archiving that evidence. In short, we need to

value our early assignments and process activities as evidence-generating

activities, not as artifacts of excellence in genre production (even though

432

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 432 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

they may, in fact, be excellent). The early LN—the first narrativizing expe-

rience—becomes the essential first move in a sequence of such activities.

It may be tempting to regard our shopping list of future evidence

(Figure 1) as an oversimplified assessment or to lament the loss of more

traditional indicators of excellence, such as those found in common col-

lege writing rubrics. However, we have found that the shopping list actually

helps us make better use of the more traditional indicators of excellence

than the rubrics in which they are commonly found. For example, we are

not recommending that teachers abandon holistic evaluation of the LN;

we are simply suggesting that holistic evaluation be moved to formative

rather than summative assessment. In fact, we suggest that the shopping

list be followed by a list of strengths—possibly copied and pasted from

the draft—and goals—either that emerge from the strengths above or that

emerge from elements also copied and pasted from the student’s draft

(Figure 1). We see several benefits in this approach to assessment: (1) it

models how to derive claims from evidence; (2) it models for students how

to reflect in the way that we will use reflection—looking back at what hap-

pened and using the evidence we find to formulate goals for future work;

(3) it builds trust that we will only grade what we say we will grade—that

is, not only already-excellent writers will be rewarded for their hard work;

and (4) it can encourage risk taking when students come to be convinced

that the risks they take do not need to be successful in order to be useful.

Furthermore, as indicated in Figure 2, the criteria for summative assess-

ment detailed in the grading form define the writing experience that each

student will pursue, rather than detail levels of excellence to be assessed

by way of the final draft. The formative section of the grading form posits

goals by way of what is revealed in the draft that emerges from that writing

experience—not for the teacher to have the final word on the draft, but for

the teacher to offer preflective comments to be referenced, potentially, in

subsequent acts of student reflection or assessment.

So, in some ways, everything changes: assignments become valued

most for the subsequent work they will inform and facilitate. In other ways,

nothing changes: assignments are evaluated as examples of the best efforts

that students can offer at the time. Most of us are already doing the latter;

it’s the former that most of us are not doing—and it’s the former that is

unlikely to happen on its own.

433

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 433 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

Figure 2. The roles of summative and formative assessment in the assessment form for the LN.

Enacting Preflection: Reimagining the Work of Teaching the

Literacy Narrative

It should be clear by now that if we want to make good on the idea that

the act of writing a literacy narrative is most useful when interventions are

directed to the process of its development, the entire course in which the

experience is situated would need to offer ample opportunities for reflec-

tion and informed goal setting. For example, the course might be organized

around a few primary assignments (experiences or “moves”) with an ar-

chitecture of supporting works—plans, assessments, drafts, peer-review

workshops, revisions, reflections—throughout. Students would announce

goals, predict outcomes, execute tasks, and predict results. Until recently,

for example, we had an assignment in our shared FYW curriculum at

Michigan State University called the “Literacy Memoir.” It was designed to

help students move toward analysis of their literacy experiences via inven-

tional moves of selection, reflection, and synthesis. We have renamed this

assignment the “Learning Narrative,” so as not to suggest (to teachers or

students) that an understanding of literacy as a theoretical concept is the

goal, or even that such an understanding is essential to facilitate the work.

Unlike literacy, which has no corresponding life in nonspecialized discourse

except as an indicator of an abstract virtue (or an unfortunate absence),

the idea of learning, while it also may participate in specialized traditions

434

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 434 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

of research and scholarship, correlates with a category of universal experi-

ence that may or may not be associated with schooling. Furthermore, we

came to recognize that the term memoir had been prompting our FYW

faculty to teach complex approaches to understanding literacy and detailed

understandings of memoir as a genre prior to having students pursue the

project—an approach in direct opposition to the “collect it, don’t correct

it” approach for which we advocate.

The renaming has been an important shift for us in making space for

stories of experience that have not yet been overdetermined by disciplinary

imperatives and that are open to further discovery (discovery that may, in

fact, include new understandings of the institutional uses of learning and of

rhetorical agency and action). “Learning Narrative,” we have found, better

names the assignment as a scene-setting establishing shot for our curricu-

lum. Recall our earlier claim: that the establishing “suggests a host of likely

possibilities and improbabilities for appropriate action and interaction that

the immediate scene cannot reveal.” The “Learning Narrative,” as we have

situated it, sets the scene for the discovery of learning at work in the ELD.

As it always has, this assignment asks students to interpret past

events and to map these onto current educational goals, projecting from a

past under construction to a present expression of self and to a future yet

to be built. Insofar as the project asks students to reflect on experiences

that may be realized as assets for education, it is a literacy narrative—but

the shift in name reflects our emphasis on the invention and reflection

enabled by the narrative act (in contrast to its potential to assess students’

understandings of literacy as a theoretical concept or its overt goal to teach

about literacy). We intend to field understandings of learning that students

choose to investigate—something none of them first need to be taught how

to assess or to find. We have all learned something worth discussing. In this

way, we announce and attempt to make good on a central premise of the

assignment and our FYW Program: each student is sufficiently prepared to

begin the course. As Bump maintains in the afterword of Mics, Cameras,

Symbolic Action: “I am a writing teacher; I teach writers” (Halbritter 235).

So it goes with writing teachers.

In “It’s Never about What It’s About: Audio-Visual Writing, Experien-

tial-Learning Documentary, and the Forensic Art of Assessment” (Halbritter

and Lindquist), we describe the ELD as the central piece of “an approach

435

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 435 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

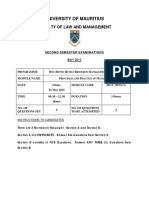

Figure 3. Assignment prompt for the ELD.

to writing instruction that is also, in its essential operations, an approach

to assessment” (317). Notice, in Figure 3, the ELD assignment prompt an-

nounces criteria for success (“specific guidelines” and “things to consider”)

that forecast the very means for evaluation evident in the ELD assessment

form (Figure 4).

The ELD is facilitated by the scaffolding of a curriculum to enable

students to produce and archive the sorts of evidence that will best be put to

use in subsequent acts that Scott calls “further interrogation and reflection.”

436

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 436 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

Our faith in the process goes to our central premise about literacy

itself, one informed and supported by a vast corpus of research on the

sociocultural nature and uses of literacy: that any act of literacy entails

not only genre-specific understandings but also situated awarenesses of

socio-rhetorical implications and engagements. With this in mind, stu-

dents will differ in the learning they will need to prioritize. The curriculum

we recommend—bookended by the LN and the ELD—attempts to help

students self-diagnose the learning they need most—not only to correct

deficits and amplify strengths but also to model how to manage successfully

the complexity of their ongoing development subsequent to the end of the

semester. We can’t, as we like to say, “get them all learned up.” However, we

can help them identify learning by way of their writing experiences and

to project goals from that learning onto their future development—not in

order to solve problems, but in order to continue addressing problems in

informed ways.

We suggest that it is important to scaffold not only the stuff inform-

ing eventual reflection—the ELD—but also using the “small stories” stuff

to support building trust in reflective writing itself—and in what are likely

unfamiliar means for learning writing. Students will probably not immedi-

ately trust these new methods. Small, early victories (e.g., demonstrations of

productive uses of informed reflection—of the successful uses of inaccurate

proposals and misdiagnosed revision strategies) are essential to gaining

students’ trust that this is not yet another system designed to use their

experiences as means for punishing them for their failures to conform to

an expected standard performance of excellence. In short, in a pedagogy

that attempts to make the most of students’ experiences of learning by way

of literate activities, the productive values of those experiences and the at-

tempted sharing of those experiences must be demonstrated early and often.

Once students perceive that they will not be punished for making false starts

and uninformed early plans, but instead will be led to make use of those

performances as evidence of their development (not merely their deficits),

students may be able to lean into the unfamiliar work of elucidating plans

that represent their best fledgling attempts—not as scripts for how they will

proceed, but as snapshots of their thinking prior to engaging the process

of pursuing the writing project(s). The reflection, in and of itself, will not

expose the learning by way of its miraculous potencies; rather, the assign-

ment sequence will shift the burden of demonstrating success to the final

reflection as taught. See, for example, the ELD assessment form in Figure 4.

437

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 437 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

Figure 4. Assessment form for the ELD.

All of this brings us back to the pedagogical affordances of narrative—

of storytelling. Sonja Schenk and Ben Long announce the basic structure

for most Hollywood stories as the “three-act structure” of “setup, complica-

tion, and payoff ” (15)—or, as they explain, “Act I: Introduce the hero; Act

II: Torture the hero; Act III: Save the hero” (16). The very structure of such

storytelling bucks against a structure of successes as not only foregone

conclusions but also as the product of failure-free processes—as logical

end results of already all-learned-up students who, of course, demonstrate

that they continue to be all learned up. Rather, the storytelling structure,

to be successful, demands and needs failures and missteps and challenges

438

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 438 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

in order to provide perspective on the sorts of hardships that the “hero”

must overcome. Both missteps and successes define each story of learning

by way of experience. In order for the story of learning by way of literate

acts to be compelling and for it to be a documentary story—not simply a

story of invention—we will need careful scaffolding of process activities

and archiving of documentary “footage” (teacher comments, peer-review

responses, plans, revisions, reflections, drafts) from which students will be

able to discover (and cite) their stories of learning.

A Final Reflection

We have suggested that literacy narratives can be an important part of a

curriculum designed to encourage students to understand themselves as

developing learners and students. We know that there is great potential for

LNs—conceived as opportunities for narrativizing—when invited within a

scaffolded curriculum of collaborative narrative inquiry, to educate teach-

ers about the literate lives of their students—to help teachers “know” their

students in ways unavailable to them without such deliberate collaborative

inquiry. The goal of the curriculum we have described is twofold: (1) for

students to invent life stories that serve their current educational projects,

and (2) for students to acquire transferable rhetorical knowledge through

the practice of narrative inquiry. With such a goal in mind, the primary

pedagogical content in the course becomes instruction in methods for

facilitating and scaffolding literacy narratives. As we have seen, such a

course operates differently from a course that begins with a consideration

of definitions of literacy for the purposes of inviting students to create nar-

ratives that could plausibly function as stories of literacy, one that positions

LNs as examples of “personal narrative” or “memoir,” and that assesses the

products of the LN as more or less successful examples of this genre. Instead,

we have suggested using early storytelling opportunities to set in motion

an ongoing series of interventions in the development of the learning self

who is engaged in the project of discovering the uses of writing for or as

inquiry. This approach entails repositioning literacy as a concept in order to

better facilitate discovery of, and reflection on, students’ own experiences.

In the spirit of reflecting and goal setting, we leave you with these

thoughts. In reflecting on what we have learned so far, and the work yet

ahead of us, what we describe here is a pedagogical approach that moves

from teaching narratives to learning via narrativizing. This seems like a good

439

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 439 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

start toward a more fully developed understanding of the affordances of a

theorized storytelling practice for teaching and learning. But there is more

yet to be done, more yet to be known, about how stories work for and on

their tellers, and how we can best realize their potential for the purposes

of FYW instruction. There is, for example, a rich corpus of interdisciplin-

ary work in memory and trauma studies that will be relevant to this goal,

as well as a body of ethnographic work directed to the question of cultural

variation in storytelling practices.

Several years into our own enactment of this pedagogy, we have learned

a few things: (1) that we continue to identify and enact possibilities for and

improvements on our methods for delivering the curriculum; (2) that our

specific realizations of the curriculum are precisely that: ours—not specifi-

cally portable to other programs or contexts; and (3) that the underlying

operation of the pedagogy and the resulting ELD is portable but must be

guided by the sorts of stories that each institution most wants students to

be able to tell. In this spirit, we have offered you our own LN with the hope

that you may reflect on and learn from it.

So it goes with literacy narratives.

Notes

1. In this piece, we describe the goals and methodology of the LCM project. It

is not our purpose here to fully elaborate the discoveries of this project, but

to point at it as a set of moves and learning experiences that have informed

our work as writing teachers. We describe our rationale and approach to

that project as follows: “Research interviews—as scenes of production—can

be strategically sequenced to elicit narratives as inventive practice: like any

other human encounter, an interview is necessarily rhetorical (and therefore

interactive and scenic), and it can be intentionally arranged in a sequence

of other such encounters to (further) exploit the inventive potential of time,

already implicit in the temporal practice of narrative. The research design we

have developed has four phases, all of which use videotaped interviews as the

primary method of data collection . . . .[W]e begin with a scaffolded interview

sequence (Phases 1 and 2) to discover domains of practice—forms of inven-

tion, communication, and sponsorship—and to identify emergent narrative

arcs. After eliciting themes and topoi relevant to students’ literacy practices,

we move to (researcher-sponsored) participant-generated video documents of

relevant sites, practices, and sponsors (Phase 3). Finally, we join participants

440

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 440 2/15/19 8:51 AM

Lindquist and Halbritter / Documenting and Discovering

to collaboratively select, visit, and videotape scenes of literacy practices and

sponsors in the field (Phase 4)” (Halbritter and Lindquist, “Time” 175).

2. The means for “operationalizing discovery” we developed through the Lit-

eracyCorps Michigan project have continued to inform our understanding of

how learning experiences might be facilitated in strategically scaffolded scenes

of inquiry. The writing classroom, we came to understand, is one such scene.

3. In their recently published study of reflection (“Revision and Reflection: A

Study of [Dis]connections between Writing Knowledge and Writing Practice”),

Lindenman et al. follow Naomi Silver and Kara Taczak in describing reflection

as “an activity of purposeful meditation on one’s experiences” (582)—an un-

derstanding of the practice that directs our work, as well. The authors of that

piece, however, position reflection differently: that is, they see writing itself as

the goal—better writing—rather than as a means for self-discovery. The cur-

riculum they describe does feature strategic (reflective) interventions, but it

has a different exigency—and also a “revision assignment” that accompanies

the final reflection. We are looking to produce not, as a first priority, more well-

executed writing—but rather, writers with better senses of their educational

missions and more confidence that they can make serve their own purposes in

the future. In contrast to the authors of this piece, we treat reflective narratives

not primarily as indicators of real writing, but (themselves) as real writing.

4. For a fuller discussion of the idea of preflection, see Halbritter and Lindquist

(“Witness”). Here we describe preflective pedagogy as one in which “reflection

is driven by five primary moves for each student: what I planned to do, what I

did, what worked well, goals that have emerged as significant, and means for

achieving these goals” (47–48). A central feature of this preflective pedagogy

is that it “works by revaluing assessment criteria that readers most often con-

sider to be most important: those concerning the quality of the final product.

Instead, preflective pedagogy places high value on other criteria to make its

determinations: what was said in the project proposal, what advice mattered,

what went wrong, what didn’t work. Consequently, preflection may encourage

risk by devaluing the excellence of the final product. If those products suck or

don’t work, students may still profit from their hard work by using these failures

as the catalysts for articulating specific writing goals” (48).

5. In keeping with Ed White’s recommendations cited in Lindenman et al.—for

teachers “to focus their evaluative attention primarily on the reflective essay

instead of deeply reading the oeuvre of revised essays within the portfolio” (593,

qtd. in Lindenman et al. 604)—we agree that the reflective essay “centers on

students’ own assessments of their work” (594, qtd. in Lindenman et al. 604).

441

h413-445-Feb19-CCC.indd 441 2/15/19 8:51 AM

CCC 70:3 / february 2019

However, our approach is not aimed at increasing “efficiency and consistency

in grading portfolios” (594, qtd. in Lindenman et al. 604). White’s concerns

here are certainly valid within a portfolio approach. And while our archiving

and preflective approach has much in common with portfolio approaches, it

differs in one fundamental way: our approach is not aimed at the subsequent

improvement of any previously authored student text. Rather, our approach

treats the final reflective move as an informed commentary about each stu-

dent’s learning in order for each student to, in turn, project informed goals and

means for pursuing those goals. Our approach, in short, is aimed at producing

better-informed writers, not better drafts. Our approach simplifies and makes

available summative evaluation criteria to facilitate the primacy of formative

evaluation. Each assignment—much as we have described in this work focused

on the initial literacy/learning narrative—is valued most in our approach as a

writing experience that happens to yield a written product. In our approach,

the shortcomings of each written product are as potentially valuable as the

overt successes.

6. Lindenman et al. mention this “teacher-pleasing” function with respect to

reflective narratives themselves: “In addition to the idea that such assessments

fall prey to what Kathleen Blake Yancey calls the ‘schmooze factor,’ in which

students use this rhetorical space to ingratiate themselves with the teacher by

crafting a neat package of the purported gains they think the instructor wants

to see (‘Dialogue’ 100)” (Lindenman et al. 588).