Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mango PHT PDF

Uploaded by

Viji ThulasiramanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mango PHT PDF

Uploaded by

Viji ThulasiramanCopyright:

Available Formats

Quest Journals

Journal of Research in Agriculture and Animal Science

Volume 4 ~ Issue 5 (2016) pp: 04-09

ISSN(Online) : 2321-9459

www.questjournals.org

Research Paper

Evaluation of Postharvest Handling and Marketing of Mango (Mangifera

Indica) in Ghana; A Case Study of Northern Region

Akurugu, G. K.*1, Olympio, N. S 2, Ninfaa. D. A.3, Karbo, E.Y4

1

Food And Drugs Authority, P. O. Box 291, WA- Upper West Region, Ghana.

2

Kwame Nkrumah University Of Science And Technology, Department Of Horticulture, Kumasi, Ghana

3

Department Of Ecological Agriculture, School Of Applied Science And Arts, Bolgatanga Polytechnic,

P.O. Box Bolgatanga, Ghana

4

N.J Ahmadiyya Training College. P.O.Box 71 Wa Upper West Region, Ghana.

Received; 16 October 2016 Accepted; 18 November 2016; © The author(s) 2016. Published with

open access at www.questjournals.org

Abstract: A survey conducted in the Northern Region of Ghana to evaluate the postharvest handling of mango

fruits from the farm gate to the market. The study mainly aimed to determine the factors that contribute to

postharvest losses of mango fruits in the region. Data recorded from the research was analyzed using the

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0. The study revealed that the varieties being

cultivated by the farmers in the Region for both export and local markets were; Keitt, Amelie, Kent and Zill. It

was also realized that sellers purchase these varieties at the full ripe stage, compelling farmers to harvest at

that stage and causing fruits to deteriorate faster. Besides, both the farmers and sellers stored the harvested

mango fruits in baskets, boxes, spread on floor or heaped on the ground, which caused fruits to senescence

early. From the study, the causes of postharvest losses in the Northern region among mango farmers and sellers

were found to include poor harvesting practices, storage and packaging methods. The results also showed that

anthracnose disease affected the matured fruits on the field especially Keitt, which led majority of the farmers to

remove the plants from their fields. It was obvious from the study that market women purchased their fruits at

full ripe stage which deteriorate faster and that demand compels most of the farmers to harvest at this stage.

Educating the sellers and farmers on harvesting at mature green stage will enable them keep their fruits longer.

The study also revealed that, there is no proper storage facility for the market women and the farmers to store

their produce after harvesting. This has created serious economic loses to all the actors in the supply chain of

the fruits. This calls for proper storage facility in future for both growers and sellers in the region

Keywords: Management, Mango, Market, Postharvest, Producers, Sellers

I. INTRODUCTION

The mango fruit (Mangifera indica L.) is one of the most popular fruits in many countries among

millions of people in the world. In the tropical areas, it is considered to be the choicest of all indigenous fruits.

Mango, as an emerging tropical fruit, is produced in over 90 countries worldwide with a production of over

28.51 million metric tons in 2005. Asia accounts for approximately 77% of global mango production, and the

Americas and Africa account for approximately 13% and 9%, respectively (FAOSTAT, 2007). Currently, only

about 3% of the world production of mango is traded globally representing a noticeable increase over the

quantities traded 20 years ago (Evans, 2008).

Mango belongs to the Anacardiaceae family to which cashew nut and some other fruit crops belong

(Samson, 1986). The genus is native to South-East Asia and consists of 62 species. About 16 of these have

edible fruits but apart from mango, only M. caesia, M. foetida and M. odorata are regularly eaten, although they

strongly taste for turpentine (Samson, 1986).

In Ghana, fruits and vegetables are abundantly produced during peak seasons but due to lack of proper

storage and preservation facilities, the market becomes overstocked during such seasons and a large proportion

get rotten before reaching the final consumer. Alzamoraet al., (2000) has reported that about 30-50% of fruits

and vegetables harvested in developing countries including Ghana are never consumed due to spoilage during

transportation, storage and processing.

In Ghana, mango fruits are primarily consumed in the fresh state usually as dessert and sometimes as a

*Corresponding Author: Akurugu, G. K.*1 4 | Page

1

Food And Drugs Authority, P. O. Box 291, WA- Upper West Region, Ghana.

Evaluation of Postharvest Handling And Marketing of Mango (Mangifera Indica) in Ghana…

fruit drink or juice.

Consumers tend to prefer fresh fruits and vegetables rather than processed or canned food, and

postharvest losses of fresh fruits and vegetables are one of the major problems of the food industry (Borrudet

al., 1996). Surveys have revealed that a substantial portion of the harvest is wasted annually due to improper

harvesting and postharvest practices, disease and lack of facilities and technology to extend storage life.

Postharvest losses have been estimated in developed countries to range from 5-25 % while in developing

countries it is 20-50 %, depending upon the commodity (Kader, 1992). This continues to cause heavy losses in

revenue for the grower, wholesaler, retailers and exporters.

World trade in fresh mango fruit is restricted by the highly perishable nature of this climacteric fruits (Lizada,

(1993); Mitra and Baldwin, (1997), that displays characteristic peak of respiratory activity during ripening

(Tucker, 1993). Postharvest losses not only reduce the availability of mango, but also result in increase in per

unit cost of transport and marketing (Subrahmanyam, 1986).

II. METHODOLOGY

2.1 Overview Of Research Design

The research employed desk study in gathering relevant literature and secondary data. During the field

study, the research employed a survey and a case study in gathering data and information from actors and

stakeholders in the major mango producing areas in Northern Region of Ghana.

2.2 Data Collection

Data collection was based on a survey of individual mango producers, out growers, sellers and

stakeholders in the mango sector, using a set of questionnaires. The research therefore had a quantitative and

qualitative approach on empirical basis and literature review. A detailed interview guide to elicit factual and in-

depth data of postharvest; handling and marketing mango fruits was used. Questionnaires were administered to

mango farmers and sellers who were selected based on their scale of production within the Northern Region to

evaluate postharvest handling of mango fruits from the farm gate to the market. Questionnaire and interview

schedule were used as techniques for gathering data in the study.

2.3 Study Area

The Northern Region is much drier than southern areas of Ghana, due to its proximity to the Sahel, and

the Sahara. The vegetation consists predominantly of grassland, especially savanna with clusters of drought-

resistant trees such as baobabs and acacias. Between the months of May and October is the wet season, with an

average annual rainfall of 750 to 1050 mm (30 to 40 inches). The dry season is normally between November

and April. The highest temperatures reach their peak at the end of the dry season, the lowest in December and

January. However, the hot Harmattan winds from the Sahara blows recurrently between December and the

beginning of February. The temperatures may vary between 14°C (59°F) at night and 40°C (104°F) during the

day.

2.4 Survey

The survey research strategy was used to gather information and obtain a general overview of the

current postharvest handling of mango fruits in the Northern region of Ghana. The survey was carried out on

producers of mangoes and sellers in the Northern Region of Ghana. One hundred and forty nine (149)

producers and twenty one sellers (21) were selected through a selective sampling from the total number of

mango producers and sellers in the region.

2.5 Sample Size And Sampling Procedure

The study employed both probability and non-probability sampling techniques in selecting the

respondents for the study. Simple random sampling, a probability sampling method and purposive sampling, a

non–probability sampling method was employed in the sample size of one hundred and forty nine (149)

respondents of mango farmers and twenty one (21) mango sellers for the study.

2.5 Data Processing And Analysis

The data collected from the field were examined from the completed questionnaires through quality

control measures such as sorting, editing, and coding to identify and eliminate errors, omissions, incompleteness

and general gaps in the collected data. The refined data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social

Sciences (SPSS Version 17.0) and Excel, to facilitate data description and analysis. Descriptive statistics such as

cross tabulation and frequencies were employed to summarize and present the quantitative aspect of the data in

the form of tables, to facilitate interpretation and analysis using frequencies, percentages,

*Corresponding Author: Akurugu, G. K.*1 5 | Page

Evaluation of Postharvest Handling And Marketing of Mango (Mangifera Indica) in Ghana…

III. RESULTS

Stage Of Harvesting Of Mango Fruits And Marketing

The survey revealed that more than half (65.10%) of the farmers harvested their mango fruits at full ripe stage.

Thirty-two percent harvest at half ripe stage, while 80.95% of the sellers purchase their mango fruits at full ripe

and 14.29%at half ripe stage. Only 4.76% of farmers harvest fruits at physiologically matured stage (Table 1).

Table 1. Stages of mango fruit before harvesting and marketing.

Response mango farmers Mango seller

Frequency Percent (%) Frequency Percent (%)

Half ripe 48 32.22 3 14.29

Full-ripe 97 65.10 17 80.95

Physiological 4 2.68 1 4.76

matured(green)

Total 149 100.00 21

Storage Method

The study (Table 2) revealed that, 38.95% of the mango farmers in the Region stored their harvested

mango fruits by heaping them on the ground at the farm, 27.52% spread on the floor and 15.43% put them in

baskets. Moreover, 16.78% of the farmers used refrigerator to store their mango fruits and 1.34% stored in

boxes. None of the sellers interviewed stored in refrigerators or heaped on the ground, however, over fifty

percent (61.90%) of them stored their mango fruits by spreading them on the floor and 28.57% in baskets. A

few of them, 9.52%, used boxes to store mango fruits.

Table 2: Storage Methods By Farmers And Sellers

Anthracnose Diseases

It was observed from the study that 87.25% of Keitt variety is most susceptible to anthracnose, while a

small 6.71%, 3.36%, 2.68% affect Kent, Amelie and Zill varieties respectfully, at the mature green stage (Table

3)

Figure 1:Anthracnose Disease identified on mango fruits at the matured Green stage

*Corresponding Author: Akurugu, G. K.*1 6 | Page

Evaluation of Postharvest Handling And Marketing of Mango (Mangifera Indica) in Ghana…

Mango Farmers Mango sellers

Response Frequency Percent (%) Frequency Percent (%)

Wholesalers 23 15.44

Retailers 33 22.15

Middlemen 4 2.62 6 28.57

Export market 26 17.45

Farm gate 32 20.81 15 71 .43

Processors 31 21.47

Total 149 100.00 21

Table 3: Mango fruits supply chain in the Northern Region

Grading Methods Used By Farmers And Sellers

From the results of the study, less than half of the mango farmers (36.24%) of the farmers graded their

mango fruits by looking at uniformity in size and shape. Nineteen point four-six percent graded based on

mechanical damage. Moreover, 18.79% of the respondents graded based on variety. Only 12.08% of the farmers

considered flesh firmness as their grading method. On the other hand, 42.86% of the sellers graded their mango

fruits using uniformity in size and shape. Twenty-eighty point seven-five percent used skin colour and 14.29%

for free from mechanical damage. Only 4.76% of the sellers considered variety of mango.

Response Mango farmers Mango seller

Frequency Percent Frequency Percent (%)

(%)

Variety 28 18.79 1 4.76

Flesh firmness 18 12.08 2 9.52

Uniformity in size and shape 54 36.24 9 42.86

Skin colour 20 13.54 6 28.57

Free from mechanical damage 29 19.46 3 14.29

Total 149 100.00 21 100.00

Table 4: Grading Methods Used By Farmers And Sellers

Mango Farmers Mango sellers

Response Frequency Percent (%) Frequency Percent (%)

Wholesalers 23 15.44

Retailers 33 22.15

Middlemen 4 2.62 6 28.57

Export market 26 17.45

Farm gate 32 20.81 15 71 .43

Processors 31 21.47

Total 149 100.00 21

Table 5: Supply Chain Of Mango Fruits

The results of the survey conducted showed that 22.15% of the farmers sold their harvested mango

fruits through the retail outlet, 21.47% of then sold to the processors and 20.18% sell at the farm gate. Fifteen

and half (15.44%) of farmers sold to wholesalers and 2.62% to middlemen. On the other hand, more than two-

thirds of the respondents (71.43%) of the sellers purchased their mango fruits at the farm gate and 28.37% from

middlemen

Storage Method

According to results of the current study in table 6, a little less than forty percent (38.95%) of the

mango farmers stored their harvested mango fruits by heaping them on the ground at the farm, 27.52% spread

on the floor and 15.43% put them in baskets. Sixteen point seven-eight (16.78%0 of the farmers used

refrigerator to store their mango fruits and 1.34% stored in boxes. In the same way, more than fifty percent

(61.90%) of the sellers stored their mango fruits by spreading them on the floor and 28.57% in baskets. Only

9.52% used boxes to store mango fruits.

*Corresponding Author: Akurugu, G. K.*1 7 | Page

Evaluation of Postharvest Handling And Marketing of Mango (Mangifera Indica) in Ghana…

Table 6: Storage Method

Response Mango Farmers Mango Seller

Frequency Percent Frequency Percent (%)

(%)

Basket 23 15.43 6 28.57

Box 2 1.34 2 9.52

Spread on floor 41 27.52 13 61.90

Refrigerator 25 16.78

Heap on ground 58 38.93

Total 149 100 21 100

IV. DISCUSSION

The findings revealed that mango farmers and sellers harvest their mango fruits for sale based on

certain indicators. It was realized that 65.10% of the mango farmers and 80.95% of the mango sellers either

harvest or buy mangoes when they were fully ripe. On the Contrary, 2.28% of the farmers harvested when it was

physiologically matured and 4.76% of the sellers also bought mangoes when they were physiologically matured.

Lakshminarayanaet al. (1970) reported that, mangoes are usually harvested green. Harvesting usually takes

place after 15-16 weeks of fruit set when they are physiologically matured. Late harvesting may result in uneven

ripening, and can lower sugar to acid ratio. Mangoes harvested at mature but unripe (green) stage will naturally

ripen off the tree, but harvesting the fruits prematurely, however, will prevent fruit from reaching full ripeness

(Lakshminarayanaet al., 1970). Harvesting fruit at stages beyond the mature green state will also reduce their

shelf stability and shorten their fresh market life. It is therefore obvious that a lot more mango fruits are lost to

growers in the Region, since harvesting of their fruits were reported to be done at the full ripe stage. Kalra et al.

(1995) reported that mature ripe mangoes deteriorated within 6 days under ambient conditions similar to that

experienced in the Northern Region of Ghana. Malik et al. (Eds.) (2005), similarly, reported that 25 - 30% of

mango produce is lost due to improper postharvest operations; as a result, there is considerable gap between the

gross production and net availability due to improper handling by the actors involved.

The current study revealed that there are differences in the way mango farmers and sellers stored their

harvested fruits in the Northern region. It was observed that 27.52% farmers spread their harvested mango fruits

on the ground, whilst 38.93% of the farmers heaped them on the ground. For the mango sellers on the other

hand, whereas 61.90% of them spread their mango fruits on the floor after the daily sales, none of them heaped

their fruits on the ground. The commonest method being practiced by majority of the farmers (heaping of the

harvested fruits) could cause the middle of the heap to experience temperatures above the ambient, perhaps

leading to high losses. Mitra and Baldwin (1997) have recommended storage temperatures for mangoes to be

between 12º and 13º C similar to that of Jobling (2000) who also recommended that mango fruits should be

stored at temperatures above 10°C.

Pantastico et al. (1975); Raghavan and Gariépy, (1985) stated that, the basic concept of storage is to

extend the shelf life of products by storing them in appropriate conditions to maintain their availability to

consumers and processing industries in their usable form. The authors further explained that, in the natural

storage the product is left in the field and harvesting is delayed, while in artificial storage, favourable conditions

are provided, which help to maintain product freshness and nutritional quality for a longer period. The storage

methods used by both farmers and sellers in study area are likely to have negative impact on the postharvest

quality of the mango fruits treated that way, since only 16.78% of farmers use refrigeration systems to store

their fruits at the pack house.

Further findings of this study revealed that the varieties cultivated had different susceptibility to

diseases that affected matured mango fruits, especially, anthracnose. For instance Keitt variety was much more

affected by anthracnose diseases compared to the other varieties being cultivated by the farmers. According to

Fitzell and Peak, (1984); and Jeffries et al., (1990), anthracnose disease caused by Colletotrichum

gloeosporioides is one of the common but major diseases of pre-and postharvested fruits and is associated with

high rainfall incidence as well as humidity. The harvesting of Keitt takes place between June and July which is

the peak of the rainy season in the Northern Region and could be attributed to the causes. For the Northern

Region, therefore, it will be advisable and therefore recommended for farmers to concentrate on producing the

other varieties, Kent, Amelie and Zill in the wet season and plant the Keitt variety during the dry season.

V. CONCLUSION

It was obvious that market women purchased their fruits at full ripe stage which deteriorate faster and

that demand compels most of the farmers to harvest at this stage. Educating the sellers and farmers on

harvesting at mature green stage will enable them keep their fruits longer

*Corresponding Author: Akurugu, G. K.*1 8 | Page

Evaluation of Postharvest Handling And Marketing of Mango (Mangifera Indica) in Ghana…

The study revealed that, there is no proper storage facility for the market women and the farmers to

store their produce after harvesting. This has created serious economic loses to all the actors in the supply chain

of the fruits. This calls for proper storage facility in future for both growers and sellers in the region.

The research indicated that anthracnose disease caused lots of losses of mango fruit at the mature stage,

especially the Keitt variety and negatively affected most of the farmers in the Region. For this reason some

farmers had cut down trees of the Keitt variety and were replacing them with Kent and Amelie, which are able

to tolerate the disease. A method of prevention of the disease would help famers continue to cultivate and

produce the cultivar.

REFERENCES

[1]. Alzamora, S. E., Tapia. M .S. and Lopez-Malo, (2000). Minimally processed fruit and vegetables. Fundamental aspects and

applications. Aspen Publishing Company Inc. Maryland. pp 21-181.

[2]. Baldwin, E., Burns, J., Kazokas, W., Brecht, J., Hagenmaier, R., Bender, R., Pesis, E. (1999)Effect of two edible coatings with

different permeability characteristics on mango (Mangiferaindica L.) ripening during storage. Postharvest Biology and Technol.,

17, 215-226

[3]. Borrud, L., C. W. Enns; and Mickle. S. (1996). “What We Eat in America”: USDA surveys food Consumption changes. Food Review.USDA Economic

Research Service, Washington, D.C.

[4]. Evans, E. A., (2008). Recent trends in world and U.S. mango production, trade and consumption. (Publication FE718) [Internet].

Gainesville, Florida: (Published 2008). Available at: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FE/FE71800.pdf [accessed 25 June 2009]

[5]. FAOSTAT, (2007).FAO Statistics, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Online]. Available at:

http://faostat.fao.org/site/339/default.aspx. [accessed 25 June 2009]

[6]. Fitzell, R.D. and PeakC.M.. (1984). The Epidemiology of anthracnose disease of mango: inoculum sources, spore production and

dispersal. Annals of Applied Biology 104: 53-59.

[7]. Jeffries, P., J.C. Dodd; M.J. Jeger; and R.A. Plumbley. (1990). The biology and control of Colletotrichum species on tropical fruit

crop. Plant pathology 39: 343-366.

[8]. Jobling, J., (2000). Temperature management is essential for maintaining produce quality. Sydney Postharvest laboratory

Information Sheet.Melbourne Australia. [Online] Available at http:// www.postharvest.com.au. [accessed 14 August 2009]

[9]. Kader, A.A.( 1992). Postharvest Biology and Technology.An Overview.In, Postharvest Technologyof Horticultural Crops.Ed., A.A. Kader.Publication No. 3311. University ofof

California, p. 279-285.

[10]. Kalra, S., Tandon, D., Singh, B. (1995.) In Handbook of fruit science and technology: production, composition, storage and

processing. D.K. Salunkhe and S.S. Kandam (Eds.) Marcel Dekker, New York.

[11]. Lakshminarayana, S. N. V. Subhadra; and. SubramanyamH. (1970).Some aspect of developmental physiology of mango

fruit.Journal of Horticultural Science 45: 133-142.

[12]. Lizada.C. (1993.)Mango. In: Seymour, G. B., Taylor, J. E. and Tucker, G. A. (eds) Biochemistry of fruit ripening. Chapman and

Hall, London, pp 255-271.

[13]. Malik, W., Farooq, U., and Sharif, M., (2005). Citrus marketing in Punjab: Constraints and potential for improvement. The Pakistan

Development Review. [Online]. 44: 4 part 2 (Winter 2005): 673 – 694. Available at: http:// www.

pide.org.pk/pdf/PDR/2005/Volume4/673-694.pdf [accessed 15 August 2009]

[14]. Mitra, S. K., and Baldwin, E. A., (1997). Mango. In: S. Mitra (ed.). Postharvest physiology and storage of tropical and subtropical

fruits. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 85-122

[15]. Pantastico, Er. B., .ChattopadhyaT.K; and. Subramanyam.H (1975).Storage and commercial storage operation. In, Postharvest

Physiology, handling and utilization of tropical and subtropical fruits and vegetables. AVI Publishing Company. Pp.560.

[16]. Raghavan, G.S.V. and GariépyY.. (1985). Structure and instrumentation aspects of storage systems. ActaHortic157: 5-30.

[17]. Samson, J. A. (1986). Tropical Fruits, 2nd edition. Longman Group Ltd. United Kingdom, 8: pp 216-233

[18]. Subrahmanyam,K.V-(1986), “ Postharvest losses in Horticultural crops, An appraisal”, Agricultural situation in india Vol

41,August,pp,339-343.

*Corresponding Author: Akurugu, G. K.*1 9 | Page

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- NasturtiumDocument2 pagesNasturtiumViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Pentas PropagationDocument2 pagesPentas PropagationViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- PeacelilyDocument19 pagesPeacelilyViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Caladium CareDocument1 pageCaladium CareViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Sys FungicideDocument2 pagesSys FungicideViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Kavach FungicideDocument3 pagesKavach FungicideViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Kalighat PaintingsDocument8 pagesKalighat PaintingsnmiqwertyNo ratings yet

- Paththudai 4000Document2 pagesPaththudai 4000Viji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Colorado Cantaloupe: SelectionDocument2 pagesColorado Cantaloupe: SelectionViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- ZentangleDocument2 pagesZentangleViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Paasuram 30Document4 pagesPaasuram 30Viji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- B Haja Govinda MDocument31 pagesB Haja Govinda MVidyadharNo ratings yet

- BavistinDocument3 pagesBavistinViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Srirangam HistoryDocument4 pagesSrirangam HistoryViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Thiruvathirai ProcedureDocument7 pagesThiruvathirai ProcedureViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Ayur FibroidsDocument1 pageAyur FibroidsViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- ShimlaDocument3 pagesShimlaViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Chand SifarishDocument2 pagesChand SifarishViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- HorizonDocument1 pageHorizonViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Investigating Life With The Cabbage White Butterfly and Brassicas in The ClassroomDocument40 pagesInvestigating Life With The Cabbage White Butterfly and Brassicas in The ClassroomViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Cantaloupe (Muskmelon) and Honeydew: Recommended Varieties Disease Resistance Orangef LeshDocument5 pagesCantaloupe (Muskmelon) and Honeydew: Recommended Varieties Disease Resistance Orangef LeshViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Om Shanthi OmDocument2 pagesOm Shanthi OmViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Grape Diseases PDFDocument46 pagesGrape Diseases PDFViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Allamanda Neriifolia: Edward F. GilmanDocument3 pagesAllamanda Neriifolia: Edward F. GilmanViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Skyblue Clustervine: Jacquemontia Pentanthos (Jacq.) G. Don Convolvulus Pentanthos JacqDocument2 pagesSkyblue Clustervine: Jacquemontia Pentanthos (Jacq.) G. Don Convolvulus Pentanthos JacqViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Tree Factsheet: Acacia Mangium WilldDocument3 pagesTree Factsheet: Acacia Mangium WilldViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Whitefly Management in Tomato: Training Course GuideDocument14 pagesWhitefly Management in Tomato: Training Course GuideViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Natural History of MahoganyDocument3 pagesNatural History of MahoganyViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Article Wjpps 1464611223Document8 pagesArticle Wjpps 1464611223Viji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- Wild CarrotsDocument2 pagesWild CarrotsViji ThulasiramanNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hydrograph Analysis: Streamflow MeasurementDocument17 pagesHydrograph Analysis: Streamflow MeasurementUmange RanasingheNo ratings yet

- American Accounting AssociationDocument13 pagesAmerican Accounting AssociationRahmat Pasaribu OfficialNo ratings yet

- AlOmar, Dalal - Assignment ScheduleDocument4 pagesAlOmar, Dalal - Assignment ScheduleDalal AlomarNo ratings yet

- The Rectangular Coordinate SystemDocument57 pagesThe Rectangular Coordinate SystemSAS Math-RoboticsNo ratings yet

- Bevington Buku Teks Pengolahan Data Experimen - Bab 3Document17 pagesBevington Buku Teks Pengolahan Data Experimen - Bab 3Erlanda SimamoraNo ratings yet

- 8TH Social F.a-1Document2 pages8TH Social F.a-1M.D.T. RAJANo ratings yet

- Innovative Numerical Protection Relay Design On The Basis of Sampled Measured Values For Smart GridsDocument225 pagesInnovative Numerical Protection Relay Design On The Basis of Sampled Measured Values For Smart GridsNazi JoonNo ratings yet

- Determining The Location of The Sustainable Fishing Industry With Center of Gravity Method, Case Study Northeast Coast of JavaDocument6 pagesDetermining The Location of The Sustainable Fishing Industry With Center of Gravity Method, Case Study Northeast Coast of JavaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- PTD25 Series Pressure Transmitters: Features ApplicationsDocument3 pagesPTD25 Series Pressure Transmitters: Features Applicationsjim bobNo ratings yet

- Animal Breeding ManualDocument43 pagesAnimal Breeding ManualMELITO JR. CATAYLONo ratings yet

- Introduction To PhonologyDocument8 pagesIntroduction To PhonologyJunjet FamorcanNo ratings yet

- Assignment Brief Course No.:: 010303100: Functional MathematicsDocument10 pagesAssignment Brief Course No.:: 010303100: Functional MathematicsEng-Mohammed TwiqatNo ratings yet

- Thickness Determination For Spray-Applied Fire Protection MaterialsDocument6 pagesThickness Determination For Spray-Applied Fire Protection MaterialsAntonNo ratings yet

- Physics - Unit 6 - Part 1Document7 pagesPhysics - Unit 6 - Part 1Mahdi ElfeituriNo ratings yet

- Sharmila .P Big Data Analytics Assignment 1Document5 pagesSharmila .P Big Data Analytics Assignment 1dharani vNo ratings yet

- Tu 5.2.3Document56 pagesTu 5.2.3Atul SinghNo ratings yet

- Exp-2 - Blocked-Rotor Test On A Three-Phase IMDocument3 pagesExp-2 - Blocked-Rotor Test On A Three-Phase IMMudit BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Dragline Cycle TimeDocument11 pagesDragline Cycle TimeanfiboleNo ratings yet

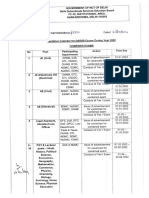

- Intllbe Calondi) R For DSSBB Elani - Durlnfl Yai (MZZDocument4 pagesIntllbe Calondi) R For DSSBB Elani - Durlnfl Yai (MZZanirudh yadavNo ratings yet

- Response of Buried Pipes Taking Into Account Seismic and Soil Spatial VariabilitiesDocument8 pagesResponse of Buried Pipes Taking Into Account Seismic and Soil Spatial VariabilitiesBeh RangNo ratings yet

- Scan 02 Mar 2021Document10 pagesScan 02 Mar 2021ARPITA DUTTANo ratings yet

- Daily Practice Problem Sheet 109: Gaurav AroraDocument3 pagesDaily Practice Problem Sheet 109: Gaurav AroraKushant BaldeyNo ratings yet

- Glencoe Algebra Unit 1 ppt3Document25 pagesGlencoe Algebra Unit 1 ppt3zeynepNo ratings yet

- Standard Operating Procedure Handover File - enDocument7 pagesStandard Operating Procedure Handover File - enrebka mesfinNo ratings yet

- Driving Collaboration Efqm ModelDocument41 pagesDriving Collaboration Efqm ModelViviane EspositoNo ratings yet

- Cbse Class 12 English The Last Lesson Revision NotesDocument2 pagesCbse Class 12 English The Last Lesson Revision NotesryumaroronaNo ratings yet

- TextbookList2021-2022 ST Paul CoventDocument17 pagesTextbookList2021-2022 ST Paul Coventkww3007No ratings yet

- Enggmath 1: ACTIVITY No.1 (MIDTERM QUIZ #1) (100-Points) Coverage: Module 1 (Algebra)Document1 pageEnggmath 1: ACTIVITY No.1 (MIDTERM QUIZ #1) (100-Points) Coverage: Module 1 (Algebra)glenNo ratings yet

- Calculation of Electric Field DistributiDocument9 pagesCalculation of Electric Field DistributiAbouZakariaNo ratings yet

- MDKA Q3 2023 Activities Report VFFDocument21 pagesMDKA Q3 2023 Activities Report VFFAlvin NiscalNo ratings yet