Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Understanding Identity Making in The Context of Sociopolitical Involvement Among Asian and Pacific Islander American Lesbian and Bisexual Women

Uploaded by

Jo WilsonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding Identity Making in The Context of Sociopolitical Involvement Among Asian and Pacific Islander American Lesbian and Bisexual Women

Uploaded by

Jo WilsonCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding Identity Making in the Context of Sociopolitical Involvement among

Asian and Pacific Islander American Lesbian and Bisexual Women

Author(s): Juan Battle, Angelique Harris, Vernisa Donaldson and Omar Mushtaq

Source: Women, Gender, and Families of Color , Vol. 3, No. 2 (Fall 2015), pp. 209-226

Published by: University of Illinois Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/womgenfamcol.3.2.0209

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/womgenfamcol.3.2.0209?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Women, Gender, and Families of Color

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Understanding Identity Making in the Context of

Sociopolitical Involvement among Asian and Pacific

Islander American Lesbian and Bisexual Women

Juan Battle, CUNY Graduate Center

Angelique Harris, Marquette University

Vernisa Donaldson, CUNY

Omar Mushtaq, University of California, San Francisco

Abstract

This study examines how Asian and Pacific Islander American (API) lesbians and

bisexual women form identities within the context of occupying both ethnic and

sexual minority social statuses. To do so, we examine the correlates of sociopoliti-

cal involvement within minority communities among a sample of 175 API lesbian

and bisexual women. The findings suggest that feeling connected to lesbian, gay,

bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities plays the most influential role

in their sociopolitical involvement within both LGBT and people of color (POC)

communities, while comfort in racial communities plays a negative role on LGBT

sociopolitical involvement but has no impact on POC sociopolitical involvement.

We then discuss implications for identity formation.

Introduction

M

any scholars have engaged with social identity theory in order to

understand how individuals understand themselves within a group

context. This theory holds that individuals, by process of interaction

within a collective identity, shape how they understand themselves (Tajfel

and Turner 1986). However, Roccas and Brewer (2002) have explained that

individuals occupy more than one position; consequently, individuals oper-

ate in the midst of competing social identities. Roccas and Brewer call this

phenomenon “social identity complexity,” in which an individual, by process

of dominance and compartmentalization between competing social loca-

Women, Gender, and Families of Color Fall 2015, Vol. 3, No. 2 pp. 209–226

©2015 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 209 9/24/15 9:20 AM

210 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

tions, defines her identity per social situation. While we affirm the notion

that individuals occupy different social statuses, we question the extent to

which behavior functions as a marker of identity, especially in the context

of competing identities. That is, in the midst of competing identities, how

do individuals not only reconcile their competing identities but also how

do these individuals behave as a result of forming these identities? Thus,

in order to understand how social identity complexity theory engages the

idea of action, identity construction, and behavior, we conducted a study

focusing on Asian and Pacific Islander American (API) lesbian and bisexual

women and their sociopolitical involvement. This study assesses how these

women negotiate their identities in both API and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and

transgender (LGBT) communities by examining these individuals’ social ties

and connectedness to their communities.

To apply social identity complexity theory to API lesbian and bisexual

women, we examine the impact that feelings of community support and con-

nectedness have on one’s sociopolitical involvement as a case example. Com-

munity connectedness provides emotional and social support (Bourhis et al.

2009). Community connectedness is even more vital for those experiencing

multiple forms of oppression (Rust 2000; Reynolds and Pope 1991). As a

group who often experiences a variety of oppressions—gender, sexual, racial/

ethnic, and, often, class and immigrant status—API lesbian and bisexual

women will be used to examine the impact that community connectedness

and identity play on sociopolitical involvement.

Feelings of belonging and acceptance are an important aspect of one’s iden-

tity formation and are directly linked to levels of sociopolitical involvement

(Flores et al. 2009; Heath and Mulligan 2008). This feeling of belonging is heav-

ily influenced by one’s social location and role within their social group (Yuval-

Davis 2006). Exclusion, oppression, and isolation increase the importance of

belonging to social groups (Gorman-Murray et al. 2008). This is especially the

case for those who experience multiple forms of minority-based oppression,

such as those within LGBT communities of color, as they often experience

both homophobia within their racial/ethnic communities and racism within

their LGBT communities (Lehavor et al. 2009; Coloma 2004; Park 2004).

Literature Review

Social Identity Complexity

In order to examine the intersection of being part of the LGBT community

and being API and the processes associated with identity development,

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 210 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 211

we contextualize social identity complexity as a theoretical extension of

social identity theory. Social identity complexity builds upon Henri Tajfel

and John Turner’s (1986) idea of social identity. This theory holds that

individuals develop their identities through a process of “social categoriza-

tion, social identity, social comparison, and psychological distinctiveness”

(Tajfel and Turner 1986, 69). Social categorization refers to a process by

which an individual group differentiates itself from other groups. Social

comparison addresses how the group then compares itself with others to

form its own identities. Finally, psychological distinctiveness addresses

a sense of an internal/psychological alignment with a particular group

association.

However, social identity theory holds that an individual identifies with

one dominant identity, and that identity is influential in the development of

her self-concept. To complicate social identity theory, Roccas and Brewer

(2002) offer their notion of social identity complexity in which identity is

formed through an intersection of different communities as opposed to

one dominant identity. In order to form identities in the midst of two or

more communities, Roccas and Brewer outline how identities are formed

if an individual occupies two or more communities. If the communities do

not overlap, Roccas and Brewer argue that an individual’s identity develops

through the process of intersection, dominance, compartmentalization, and

merger (90–91). In other words, an individual can 1) define her identity based

on an intersection of the two communities, thus creating a separate identity

apart from the two initial communities—intersection; 2) choose a dominant

identity and identify with one particular group over others—dominance; 3)

maintain different identities and selectively choose to identify with one group

or another based on the situation—compartmentalization; or 4) identify

with multiple communities so that the individual expands her in-group to

be inclusive of multiple communities.

Though initially applied to the identity formation of Asian Australians,

this framework has not yet been expanded to Asian and Pacific Islander

Americans, let alone, sexual minority API women (Brewer et al. 2013) and

their sociopolitical behavior. To do this, we first describe Asian and Pacific

Islander Americans and their involvement within feminist rights movements.

This will help illustrate the complex relationship between APIs and racial/

ethnic and feminist civil rights and the complexity of political identity forma-

tion. We will then proceed to describe APIs’ current involvement with LGBT

rights and the nuances of API identity within the context of contemporary

LGBT communities.

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 211 9/24/15 9:20 AM

212 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

Intersectionality

As explained by social identity complexity theory, individuals form identi-

ties in the context of multiple groups. This framework, although useful for

explaining how individuals create identities, can be expanded by examining

how these identities are shaped by the social structure. Using black women

as her example, sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (2000) develops her notion

of intersectionality, where individuals develop a particular identity as a

result of occupying two or more statuses. Yet, where Collins departs from

Roccas and Brewer’s (2002) understanding is that she connects the develop-

ment of multiple identities and group participation to the social structure.

Collins explains, “United States Black women encounter a distinctive set

of social practices that accompany our particular history within a unique

matrix of domination characterized by intersecting oppressions” (2000,

23). Here, Collins explains the significance of the group identity “Black

women” as a distinct group that has a unique experience and is character-

ized by a particular “matrix of domination.” For Collins, this matrix of

domination entails being both black, a racial minority, and a woman, a

gendered minority. However, Collins continues, “As historical conditions

change, so do the links among the types of experiences Black women will

have and any ensuing group consciousness concerning those experiences”

(25). Here, Collins explicitly links the experiences of being a black woman

to historical conditions. Thus, it is not simply that black women encounter

an experience of being a triple minority but that this status is reinforced

by the structural conditions imposed by history. Using this framework,

we attempt to understand the relationship that API lesbian and bisexual

women have with the social structure, starting with the historical relation-

ship between their group and the United States women’s rights movement,

then moving on to explore the relationship between API women and the

nature of their ties with the LGBT community.

APIs, American Feminism, and Social Movements

To contextualize how API lesbian and bisexual women form and politically

act upon their identities, we provide a historical context that situates APIs

within, and their relationship to, the women’s rights movement. After noticing

how patriarchy functioned in the context of API struggles and organizing

political movements with their male counterparts, API women turned to

the women’s rights movement to address their concerns with sexism. For

example, Wei (1993) understands API women’s experiences to be “parallel”

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 212 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 213

(73) to the feminist movement. Nonetheless, API women found that their

culturally specific values of family and community were disregarded by white

feminist values of independence, participation in the public sphere, and the

rejection of women’s role in the domestic sphere (ibid., 74). Feeling as if their

values were overshadowed and ignored within mainstream feminist move-

ments, many API women collectively organized and engaged in separate

consciousness-raising activities, such as the involvement with separate Marx-

ist, Leninist, and Maoist “rap sessions” and other activities that separated API

women from their white counterparts (ibid.).

The schism between API women and women who participated in the

mainstream women’s rights movement illustrates an important juncture

for LGBT rights and API political involvement. While this brief discussion

reported largely on the experiences of heterosexual API women within the

women’s rights movement, it is important to recognize that the feminist

movement in the United States was largely rooted in white, middle-class

underpinnings. The lesbian and gay rights movement is a direct offshoot of

this movement in that it shares the feminist movement’s white, middle-class

framing. Thus, it is safe to assume that API lesbian and bisexual women will

navigate the LGBT community as racial/ethnic “outsiders.” API lesbian and

bisexual women occupy a space that is positioned within, and outside, the

LGBT community.

Interacting with a White LGBT Community

After situating how API feminism was at odds with the white-framed women’s

rights and lesbian and gay rights movements, we now examine how people

of color (POC) experience discrimination within the mainstream LGBT

community. Research on homophobia within communities of color often

highlights the negative impact homophobia can have not only on identity

formation for LGBT racial and ethnic minorities but also on their sense of

self-worth (Crichlow 2004; Griffin 2001; Ward 2005). A variety of factors

such as family of origin, religious beliefs, and cultural traditions may impact

one’s choice not only to “come out” to one’s families (Chan 1989; Espiritu

2010; Uba 1994) but also to accept one’s own sexual orientation as a part of

one’s identity (Loiacano 1989). For example, Connie Chan’s (1989) study,

which examines sexuality among APIs, found that only 26 percent had “come

out” to their parents, compared to 77 percent who had “come out” to other

family members and almost 100 percent of the sample who had “come out”

to friends. Chan quotes one respondent as saying, “I wish I could tell my

parents—they are the only ones who do not know about my gay identity,

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 213 9/24/15 9:20 AM

214 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

but I am sure they would reject me” (19). Those participants who found it

harder to come out in API communities felt this was because homosexuality

was viewed as taboo. Operario, Han, and Choi (2008) report that their API

gay male sample felt as if they have consistently experienced sexual stigma

and discrimination within their racial/ethnic communities. In fact, Chan

discovered that the men in her sample experienced more sexual discrimina-

tion than race-based discrimination. In her study of API women, Lora Foo

(2002) found that 87 percent of lesbians reported being verbally assaulted

because they were thought to be lesbians, while over 50 percent reported

being threatened with physical violence, and 15 percent reported physical

injury. Research argues that the stigmas associated with homosexuality are

due to the belief that homosexuality is a “White, western phenomenon”

(Chan 1989, 19). Additionally, in some Asian cultures, sexuality is not a means

by which to identify oneself (Asthana and Oostvogels 2001; Laurent 2005).

Since for many Asians, in both Asia and the United States, sexuality is not

perceived to be an identity in the same way in which Western culture views

it, this could likely help explain Singh, Chung, and Dean’s (2007) finding that

API lesbian and bisexual women were less likely to experience internalized

homophobia than were their non-API counterparts.

Racial and ethnic discrimination within the mainstream, predominately

white, LGBT community is widespread (Han 2007; Loiacano 1989; Nemoto

et al. 2003). Studies examining the experiences of APIs within the LGBT

community have found that most have felt they were overlooked within the

community or have experienced overt racial discrimination (Chan 1989;

Dang and Hu 2004). Dang and Hu (2004) found that over 82 percent of their

API respondents had experienced racism from white LGBT people. Unlike

the API lesbian and bisexual women who felt more discriminated against

because they were Asian, the men in Chan’s (1989) sample experienced more

sexual discrimination within Asian communities than racial discrimination

within the LGBT community. Overall, however, Dang and Hu found that

most of the people within their sample (53 percent) reported positive experi-

ences within the mainstream LGBT community.

LGBT POC are less likely to be involved in the LGBT community (Loia-

cano 1989). Research on the racial discrimination experienced by gay and

bisexual men of color in white LGBT communities notes the negative rami-

fications that this discrimination has on their self-esteem and their percep-

tion of self-worth (Flores et al. 2009). Lehavor et al. (2009) argued that the

connections lesbian and bisexual women feel to the LGBT community were

important for these women and provided community support. Due to the

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 214 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 215

discrimination they experienced, LGBT APIs had to create safe spaces within

which they were able to build political and cultural identities that facilitated

the integration of their queer, ethnic, and gendered selves. Safe spaces, such

as these, protected LGBT APIs in their struggle against racism, sexism, and

homophobia emanating from society, their communities, and their families

(Aguirre and Lio 2008). Understanding the way in which LGBT POC per-

ceive of and experience racial discrimination may shed light on their level

of sociopolitical involvement within both LGBT and POC communities.

One way we operationalize sociopolitical behavior is through the measure

of “civic engagement.”

Civic Engagement

Since we discussed how the women’s rights movement as a political move-

ment that involves people feeling included in their respective communities,

one way to understand how API lesbian and bisexual women feel bonded

to their community is by understanding their sociopolitical involvement or

civic engagement within their communities. Although most research that

examines civic engagement highlights an individual’s participation in political

life, civic engagement also consists of political participation, activism, and

volunteering (Galston and Lopez 2006; Putnam 1995, 2005; Skocpol and Fio-

rina 1999). Civic engagement incorporates two interconnected components:

sociopolitical involvement and community engagement.

Community engagement consists of service, activism, and volunteerism

for the benefit of one’s community (Ball 2005). Sociopolitical involvement

involves social activism and volunteerism, as well as participating in social

and cultural events. Sociopolitical involvement also contains elements of

community engagement and is an important part of civic engagement, as it

often signifies one’s potential for civic and community activism (Harris and

Battle 2013; Putnam 2000). Research on sociopolitical involvement empha-

sizes the importance of community connectedness and feelings of belonging

(Heath and Mulligan 2008). Consequently, feelings of belonging within a

community may hold important implications for one’s level of sociopolitical

involvement.

Research maintains that civic engagement and community involvement

are particularly important to those facing multiple forms of oppression

(Balsam et al. 2011; Poynter and Washington 2005). Previous research has

examined the correlates of civic engagement, such as race, age, gender, class,

education, family, geographic location, and immigrant status (Putnam 2000;

Sander and Putnam 2006; Verba et al. 1995). Research argues that out of all

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 215 9/24/15 9:20 AM

216 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

racial/ethnic groups, blacks and whites in the United States have the high-

est levels of civic engagement, with blacks reporting slightly higher levels of

civic engagement than whites with the exception of voting (Finlay et al. 2011;

Verba et al. 1995). Compared to blacks and whites, APIs are significantly less

likely not only to vote but also to be civically engaged (Xu 2002). Much of

this decreased civic engagement has to do with the fact that APIs are much

more likely to be recent immigrants and, as such, are less likely to feel con-

nected to the political and social life of their communities and sometimes

are not legally able to vote (Jang 2009; Xu 2002). Even when taking class and

education into account, APIs are still less likely to be civically engaged than

other racial ethnic groups, including Latinos, another group that has high

immigrant and first-generation populations (Jang 2009; Xu 2002). Length

of residence and being born in the United States appear to be significant

predictors of overall political participation among APIs (Leighley and Vedlitz

1999; Wong 2011).

There appears to be little difference in political participation and voting

between API women and men (Lien 2011). Research maintains that levels

of civic engagement greatly increase with education (Brand 2010; Campbell

2009; Hoene 2011; Jang 2009). The higher the educational attainment of

APIs, the more likely they are to have a party affiliation and vote (Hoene

2011). Although a higher income increases one’s chances of registering to

vote among APIs, it does not necessarily increase their likelihood to vote

(Jang 2009).

Age cohort appears to be the largest determinant for civic engagement

among Americans overall, with older Americans participating in more civic

activities than younger Americans (Putnam 2000; Sander and Putnam 2006).

Among APIs, age does appear to have a significant impact on voting reg-

istration rates; however, as with income and education, it does not greatly

impact voter turn-out rates. Even though political participation and voter

turn-out rates remain traditionally low for APIs, they do have a strong his-

tory of community engagement and activism (Aguierre and Lio 2008). For

example, “[T]hey have organized worker cooperatives, mobilized community

support, and led worker struggles” (ibid., 6).

As the above research argues, feelings of belonging play a central role in

one’s level of sociopolitical involvement. Research does not sufficiently assess

the influence that feelings of belonging have on the sociopolitical involvement

of LGBT racial/ethnic minorities. To investigate intragroup marginalization

and its effect on feelings of belonging and sociopolitical involvement within

both LGBT and POC communities, this paper will examine sociopolitical

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 216 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 217

involvement among API lesbian and bisexual women. API lesbian and bisex-

ual women provide the framework through which to examine intragroup

marginalization and the impact it has on feelings of belonging within minor-

ity communities, as they often experience multiple forms of oppression. Thus,

we pose the following hypothesis: API lesbian and bisexual women will feel

a greater sense of belonging and will consequently exhibit higher rates of

sociopolitical behavior within their own communities of color than within

the LGBT community.

Methodology

The data used in this paper come from a 2010 survey administered by the

Social Justice Sexuality Project. The purpose of this project was to collect

data on the experiences of LGBT POC concerning the following five themes:

identity (both racial and sexual), physical/mental health, family, religion/

spirituality, and sociopolitical involvement. Data were collected from over

5,000 respondents throughout the United States and Puerto Rico. The subset

of 175 API lesbian and bisexual women was analyzed for this paper. Since

the analysis focuses on the experiences of API lesbian and bisexual women,

we have focused on the data from the API lesbian and bisexual women in

our sample.

The API lesbian and bisexual women within this sample were between

18 and 78 years of age, with a mean age of 30. This sample of women is

relatively young; a little more than half reported being between the ages of

25 and 49 (54.2 percent), while another third were young adults between 18

and 24 (36.5 percent). A little less than one-third of the respondents identi-

fied as single (32.3 percent), and about one-fifth are parents (20.7 percent).

Most respondents live in urban areas (72.1 percent), and 6 percent live in

the southern part of the United States. The average respondent identified as

being politically liberal.

Respondents were also fairly educated; a majority of the sample had at

least some college education or higher (82.1 percent). Further, while the aver-

age respondents made $20,000–$29,999 per year, just over one-fifth made

between $30,000 and $49,999 a year (21.8 percent), and over a third made

$50,000 a year or greater (37.9 percent). A majority of the respondents in

this sample were United States citizens (88.7 percent) or naturalized citizens

(5.9 percent).

Finally, although there were some heterosexually-identified women who

completed the survey (19.4 percent), they were removed from this sample, as

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 217 9/24/15 9:20 AM

218 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

the purpose was to examine the feelings of sexual-minority women. Although

heterosexuals were removed from the sample, as the literature review notes,

there is a notable amount of research that posits that APIs view homosexual-

ity as a behavior and not an identity (Asthana and Oostvogels 2001; Laurent

2005). As such, it is likely that many individuals who completed the survey,

regardless of their sexual preference, would have identified as heterosexual,

although, by Western standards, they would be viewed as homosexual or

bisexual. Nonetheless, to reduce confusion, those who identified as hetero-

sexual were removed from this sample.

Measures

To measure belonging, this paper focuses on the correlates of sociopolitical

involvement among a sample of API lesbian and bisexual women within both

LBGT and POC organizations and events. Sociopolitical involvement was

measured by the frequency with which respondents participated in political

and sociocultural events, read LGBT or POC newspapers and magazines,

used LGBT- or POC-focused social networking sites, received services from

LGBT or POC organizations (such as counseling), and/or donated money

to LGBT or POC organizations. This survey looked at questions relevant to

the LGBT community and not necessarily the people of color community.

The first dependent variable, LGBT sociopolitical involvement, was con-

structed from six survey items that measured the frequency of participation

in LGBT groups, organizations, and activities (alpha = .744). The dependent

variable, POC sociopolitical involvement, was similarly constructed from

the six survey items that measured the frequency of participation in POC

groups, organizations, and activities (alpha = .821).

Research shows that sexual identity has a positive impact on civic engage-

ment among lesbians and gays (Flores et al. 2009; Han 2007; Heath and

Mulligan 2008; Lehavor et al. 2009). Research further maintains that racial

identity impacts the civic engagement of people of color (Verba et al. 1995).

Research overlooks the importance of identity, more specifically, sexual and

racial identity on the community engagement and, in particular, the socio-

political involvement of API lesbian and bisexual women.

Additionally, seven independent variables that measure community and

identity were included in this analysis. Five of the independent variables

measured community connectedness, levels of comfort and support, and

“outness.” Two independent variables measured the importance of sexual

and racial identity. “Connected to LGBT Community” is created from three

combined survey items that measured how connected respondents felt to

the LGBT community, other LGBT people, and the problems facing the

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 218 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 219

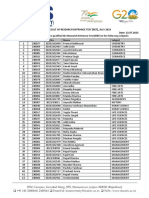

Table 1. LGBT and POC Sociopolitical Involvement Among Asian Women N= 174

Range Mean Std. Dev. Alpha

Dependent Variables

LGBT Sociopolitical Involvement 1–6 2.948 0.997 .744

POC Sociopolitical Involvement 1–6 2.500 1.134 .821

Independent Variables

Community

Connected to LGB Community 1–6 4.071 1.213 .722

Outness 1–5 3.680 1.129 .895

Family Support 1–6 4.20 1.661

Comfort in LGBT Communities 1–6 4.823 1.597

Comfort in Racial Communities 1–6 3.839 1.546

Identity

Sexual Identity Importance 1–6 5.02 1.230

Racial Identity Importance 1–6 4.26 1.619

LGBT community as a whole. The second independent variable, “Outness,”

consists of six items that examine how “out” (or open about one’s sexuality)

respondents were with their family, friends, religious community, co-workers,

neighbors, and within their online communities. The third independent vari-

able, “Family Support,” measured the level of support respondents felt from

their families. “Comfort in LGBT Communities” and “Comfort in Racial

Communities” are independent variables that measure the frequency with

which respondents felt comfortable in the LGBT community regardless of

their race and comfortable in their racial/ethnic communities regardless of

their sexual identity.

The final two independent variables measured identity. “Sexual Identity

Importance” measured how important the respondent’s sexual orientation

is to her identity. “Racial Identity Importance” measured how important the

respondent’s race/ethnicity is to her identity.

Demographic variables were also examined. These include relationship

status; whether they are a parent; age; whether they are foreign born; if they

are a resident of an urban, suburban, or rural area; if they are a resident of the

southern part of the United States; political views; education; and income.

Models

To measure the relationship between community, identity, and various

demographic variables—such as income, age, political views, education,

and residential status—on the sociopolitical involvement of API lesbian

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 219 9/24/15 9:20 AM

220 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

and bisexual women, four multivariate regression analyses were performed.

The first examined community connectedness on a level of LGBT sociopo-

litical involvement. The second model examined community connected-

ness and identity on a level of LGBT sociopolitical involvement. The third

model examined community connectedness on a level of POC sociopolitical

involvement. Finally, the fourth model examined community connectedness

as well as identity on level of POC sociopolitical involvement.

Results

In the first two models, LGBT sociopolitical involvement was the dependent

variable (see Models I and II). Women who felt more connected to the LGBT

community had higher levels of LGBT sociopolitical involvement. Yet, out-

ness and the level of comfort these women had with the LGBT community

did not impact their level of LGBT sociopolitical involvement. Family support

also had no impact on LGBT sociopolitical involvement. However, comfort

in racial communities negatively impacts these women’s LGBT sociopolitical

involvement. All of these relationships held when the importance of identity

measures were introduced into the models (see Model II) and when several

demographic variables were included (see footnote on Table 2).

Table 2. Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for the LGBT and POC Sociopolitical

Involvement Among Asian Women (betas in parentheses)

Dependent Variables LGBT Dependent Variables POC

Sociopolitical Involvement N=174 Sociopolitical Involvement N=175

Model I Model IIa Model III Model IVa

Independent Variables

Community

Connected to LGBT Community .134*** (.137) .280*** (.341) .258*** (.276) .259*** (.277)

Outness .032 (.036) .024 (.027) -.073 (-.072) -.063 (-.063)

Family Support -.018 (-.030) -.014 (-.023) -.059 (-.086) -.060 (-.088)

Comfort in LGBT Communities .025 (.040) .017 (.027) -.055 (-.078) -.054 (-.076)

Comfort in Racial Communities -.179** (-.278) -.182** (-.283) -.103 (-.142) -.105 (-.144)

Identity

Sexual Identity Importance -.052 (-.064) -.024 (-.026)

Racial Identity Importance -.038 (-.062) .021 (.030)

Constant 2.455*** 2.834*** 2.606*** 2.598***

Adjusted R2 .170 .170 .116 .106

† p≤.10 *p≤.05 **p≤.01 ***p≤.001

a. The following demographic variables were included: single, has ever parented, age, foreign born, big

city resident, south resident, political views, education, and income. However, none were significant and

therefore did not impact the above results.

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 220 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 221

When POC sociopolitical involvement was the dependent variable (Mod-

els III and IV), similar results were produced. This could be given that the

women in the sample represent participation in both LGBT communities as

well as POC communities. Therefore, as with LGBT sociopolitical involve-

ment, when examining POC sociopolitical involvement for these women,

connection to the LGBT community had a positive impact; outness, family

support, and comfort in the LGBT community had no impact (see Model

III). Interestingly, comfort in racial communities had a negative impact on

their LGBT sociopolitical involvement (see Models I and II), but it had no

impact on their POC sociopolitical involvement (see Models III and IV).

As with LGBT sociopolitical involvement described in Model II, relation-

ships held with the addition of the identity variables, as well as when several

demographic variables were included (see footnote on Table 2) in Model IV.

Although comfort in LGBT communities was not a significant predic-

tor of LGBT or POC sociopolitical involvement (see Models I through IV),

comfort in racial communities negatively impacted LGBT sociopolitical

involvement (see Models I and II), but not POC sociopolitical involvement

(see Models III and IV). Similarly, the importance of sexual and racial identity

was not a significant predictor of LGBT sociopolitical involvement or POC

sociopolitical involvement.

Discussion

The findings of this study support previous research that claims sociopolitical

involvement is determined by one’s feeling of connectedness to one’s com-

munity (Flores et al. 2009; Heath and Mulligan 2008). Findings, however,

contradict the claim that income, education, age, and immigrant status play

a role in this sociopolitical involvement (Putnam 2000; Sander and Putnam

2006; Verba et al. 1995). These findings may result from our analysis of socio-

political involvement, whereas the other studies examined civic engagement.

In addition, whereas previous research examined the experiences of Ameri-

cans in general, this paper is focused on API lesbian and bisexual women.

Regardless, this study highlights the need for more research in this area.

Although our findings that connectedness to the LGBT community influ-

enced LGBT sociopolitical involvement are not surprising, it is somewhat

surprising that it also influences POC sociopolitical involvement within this

sample of women. It is possible that the support and feelings of acceptance

that API lesbian and bisexual women experience within the LGBT communi-

ty positively influences their self-concept and, thus, their level of connected-

ness to POC communities. Unexpectedly, comfort in racial communities had

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 221 9/24/15 9:20 AM

222 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

a negative impact on the LGBT sociopolitical involvement of these women

but no impact on their POC involvement. It appears that, if they do not feel

comfortable in their racial communities, they will be less likely to be involved

in the LGBT community. Thus, we are able to accept the hypothesis that API

lesbian and bisexual women feel more comfortable dealing with communities

of color as opposed to LGBT communities.

If there was high family support and high comfort in ethnic commu-

nity (indicating an identification with one’s ethnic background), political

involvement diminished both in LGBT and people of color communities.

This reinforces findings that demonstrate low sociopolitical involvement

based on high ethnic ties (Green et al. 2013). Likewise, this could show how,

for those who are tied to one’s own ethnic background, it would be especially

difficult to see one’s self in the context of a pan-identity (an identity that

encompasses different identities, for example, being Vietnamese American

instead of Asian American).

On the other hand, increased “outness” meant a lower identification and

involvement with POC communities and a higher involvement in the LGBT

community. In addition, an increased importance of sexual identity meant

a lower participation with POC communities. This means that a dominance

effect of identity occurs because these women choose between their ethnic

identities and their sexual identities.

This study’s implications are interesting to note, as feeling connected to

the LGBT community is the most important predictor for involvement in

both LGBT and POC communities for the women in our sample. Impor-

tantly, comfort in racial communities has a negative impact on their LGBT

involvement. As this study has shown, the potential for discrimination these

women may experience within the LGBT community has great implications

on their lack of participation in social events and issues for not only the LGBT

community but for communities of color as well.

The primary strengths of this study include the geographic representa-

tion and diversity of the sample. The study’s primary limitation is the sample

population. As these women were recruited at both LGBT and POC events,

it is likely that these women are not truly representative of API. Therefore,

arguably, this particular sample may be more likely to participate in sociocul-

tural activities and events, or they may believe that this participation is vital

to their identity development, as opposed to the women who do not attend

these events. In addition, these women have higher incomes, are younger,

and are more educated than perhaps what would be found in the general

population of API women.

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 222 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 223

The primary finding of this study underscores that the most important

variable for sociopolitical involvement is feeling accepted by the LGBT com-

munity. Future research should explore whether feelings of belonging within

POC communities are as important as feelings of belonging within LGBT

communities. Additionally, future research should study the influence of

community connectedness on volunteerism within both LGBT and POC

communities. Finally, more research is needed to examine sociopolitical

involvement among API gay and bisexual men to see the role of gender as

it relates to the findings presented here.

Conclusion

Using sociopolitical indicators as a marker of identity, our results found that

the API women in our sample value their connection to their ethnic com-

munities at the expense of the American LGBT community. Drawing on the

literature, we then see how API lesbians and bisexual women create their

identities. The results appear to illustrate a trade-off between the identities

of being an ethnic minority or being LGBT. In terms of social complexity

theory, this means that a dominance effect occurs as these women reconcile

their ethnic background with their participation in the LGBT community. In

other words, one identity “dominated” the other three identities as indicated

by relationships between perceived connectedness to a particular community

and behavior. Given how API lesbian and bisexual women reconcile their

identities, this then means that there could be added psychological stress on

these women to engage in such “reconciliation” processes.

References

Aguirre Jr., Adalberto, and Shoon Lio. “Spaces of Mobilization: The Asian American/Pacific

Islander Struggle for Social Justice.” Social Justice 35, no. 2 (2008): 1–17.

Asthana, Sheena, and Robert Oostvogels. “The Social Construction of Male ‘Homosexu-

ality’ in India: Implications for HIV Transmission and Prevention.” Social Science and

Medicine 52, no. 5 (2001): 707–21.

Ball, William J. “From Community Engagement to Political Engagement.” Political Science

and Politics 38, no. 2 (2005): 287–91.

Balsam, Kimberly F, Yamile Molina, Blair Beadnell, Jane Simoni, and Karina Walters. “Mea-

suring Multiple Minority Stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale.”

Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 17, no. 2 (2011): 163–74.

Bourhis, Richard Y., Annie Montreuil, Geneviève Barrette, and Elisa Montaruli. “Accul-

turation and Immigrant/Host Community Relations in Multicultural Settings.” In Inter-

group Misunderstanding: Impact of Divergent Social Realities, edited by Stéphanie

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 223 9/24/15 9:20 AM

224 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

DeMoulin, Jacques-Philippe Leyens, and John F. Dovidio, 39–61. New York: Psychology

Press, 2009.

Brand, Jennie. “Civic Returns to Higher Education: A Note on Heterogeneous Effects.”

Social Forces 89, no. 2 (2010): 417–33.

Brewer, Marilynn B, Karen Gonsalkorale, and Andrea van Dommelen. “Social Identity

Complexity: Comparing Majority and Minority Ethnic Group Members in a Multicultural

Society.” Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 16, no. 5 (2013): 529–44.

Campbell, David E. “Civic Engagement and Education: An Empirical Test of the Sorting

Model.” American Journal of Political Science 53, no. 4 (2009): 771–86.

Chan, Connie S. “Issues of Identity Development among Asian-American Lesbians and

Gay Men.” Journal of Counseling and Development 68, no. 1 (1989): 16–20.

Choi, Kyung-Hee, Don Operario, Steven E. Gregorich, and Lei Han. “Age and Race Mixing

Patterns of Sexual Partnerships among Asian Men Who Have Sex with Men: Implica-

tions for HIV Transmission and Prevention.” Aids Education and Prevention 15, no. 1

supplement (2003): 53–65.

Chung, He Len, and Stephanie Probert. “Civic Engagement in Relation to Outcome Expec-

tations among African American Young Adults.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psy-

chology 32, no. 4 (2011): 227–34.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Coloma, Roland Santos. “Fragmented Entries, Multiple Selves: In Search of a Place to Call

Home.” In Restored Selves: Autobiographers of Queer Asian/Pacific American Activists,

edited by K. K. Kumashiro, 9–28. New York: Harrington Park Press, 2004.

Crichlow, Wesley E. A. Buller Men and Batty Bwoys. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

2004.

Dang, Alain, and Mandy Hu. “Asian Pacific American Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans-

gender People: A Community Portrait. A Report from New York’s Queer Asian Pacific

Legacy Conference, 2004.” New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Insti-

tute, 2004. Retrieved from http://thedccenter.org/peopleofcolor/docs/APACommunity

Portrait.pdf (accessed June 4, 2015).

Espiritu, Yen Le. Asian American Women and Men. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publica-

tions, 2010.

Finlay, Andrea K., Constance Flanagan, and Laura Wray-Lake. “Civic Engagement Patterns

and Transitions over 8 Years: The Americorps National Study.” Developmental Psychol-

ogy 47, no. 6 (2011): 1728–43.

Flores, Stephen A., Gordon Mansergh, Gary Marks, Robert Guzman, and Grant Colfax.

“Gay Identity-related Factors and Sexual Risk among Men Who Have Sex with Men in

San Francisco.” AIDS Education and Prevention 21, no. 2 (2009): 91–103.

Foo, Lora Jo. Asian American Women. New York: Ford Foundation, 2002.

Galston, William, and Mark Lopez. “Civic Engagement in the United States.” In Civic

Engagement and the Baby-Boomer Generation: Research, Policy, and Practice Per-

spectives, edited by L .B. Wilson and S. P. Simson, 3–19. Binghampton, NY: Haworth

Press, Inc., 2006.

Gorman-Murray, Andrew, Gordon Waitt, and Chris Gibson. “A Queer Country? A Case Study

of the Politics of Gay/Lesbian Belonging in an Australian Country Town.” Australian

Geographer 39, no. 2 (2008): 171–91.

Green, Donald P, Mary C McGrath, and Peter M Aronow. “Field Experiments and the Study of

Voter Turnout.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 23, no. 1 (2013): 27–48.

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 224 9/24/15 9:20 AM

fall 2015 / women, gender, and families of color 225

Griffin, Horace. “Their Own Received Them Now.” In The Greatest Taboo: Homosexuality in

Black Communities, edited by D. Constantine-Simms, 110–23. New York: Alyson Books,

2001.

Han, Chong-suk. “They Don’t Want to Cruise Your Type: Gay Men of Color and the Racial

Politics of Exclusion.” Social Identities 13, no. 1 (2007): 51–67.

Harris, Angelique, and Juan Battle. “Unpacking Civic Engagement: The Sociopolitical

Involvement of Same-Gender-Loving Black Women.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 17, no.

2 (2013): 195–207.

Heath, Mary, and Ea Mulligan. “‘Shiny Happy Same-Sex Attracted Woman Seeking Same’:

How Communities Contribute to Bisexual and Lesbian Women’s Well-Being.” Health

Sociology Review 17, no. 3 (2008): 290–302.

Hoene, Edward. “Asian Americans and Politics: Voting Behavior and Political Involvement.”

Senior thesis, Bemidji State University, 2011

Jang, Seung-Jin. “Get Out on Behalf of Your Group: Electoral Participation of Latinos and

Asian Americans.” Political Behavior 31, no. 4 (2009): 511–35.

Laurent, Erick. “Sexuality and Human Rights: An Asian Perspective.” Journal of Homo-

sexuality 48, nos. 3–4 (2005): 163–225.

Lehavor, K., K. F. Balsam, K.F., and G. D. Ibrahim-Wells. “Redefining the American Quilt:

Definitions and Experiences of Community among Ethnically Diverse Lesbian and Bisex-

ual Community.” Journal of Community Psychology 57 no. 4 (2009): 439–58.

Leighley, Jan E., and Arnold Vedlitz. “Race, Ethnicity, and Political Participation: Competing

Models and Contrasting Explanations.” The Journal of Politics 61, no. 4 (1999): 1092–1114.

Lien, Pei-te. The Making of Asian America through Political Participation. Philadelphia:

Temple University Press, 2001.

Loiacano, Darryl. “Gay Identity Issues among Black Americans: Racism, Homophobia, and

the Need for Validation.” Journal of Counseling & Development 68, no. 1 (1989): 21–25.

Nemoto, Tooru, Don Operario, Toho Soma, Daniel Bao, Alberto Vajrabukka, and Vincent

Crisostomo. “HIV Risk and Prevention among Asian/Pacific Islander Men Who Have Sex

with Men: Listen to Our Stories.” AIDS Education and Prevention 15, no. 1 supplement

(2003): 7–20.

Operario, D., C. S. Han, and K. H. Choi. “Dual identity among Gay Asian Pacific Islander

Men.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 10, no. 5 (2008): 447–61.

Park, Pauline. “Activism and the Conscious of Difference.” In Restored Selves: Autobiog-

raphies of Queer Asian/Pacific American Activists, edited by K. K. Kumashiro, 93–100.

New York: Harrington Park Press, 2004.

Poynter, Kerry John, and Jamie Washington. “Multiple Identities: Creating Community on

Campus for LGBT Students.” New Directions for Student Services 111 (2005): 41–47.

Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000.

———. “Tuning In, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America.”

PS: Political Science and Politics 28, no. 4 (1995): 664–83.

Reynolds, Amy L., and Raechele L. Pope. “The Complexities of Diversity: Exploring Mul-

tiple Oppressions.” Journal of Counseling and Development 70, no. 1 (1991): 174–80.

Roccas, Sonia, and Marilynn B. Brewer. “Social Identity Complexity.” Personality and

Social Psychology Review 6, no. 2 (2002): 88–106.

Rust, Paula. “The Impact of Multiple Marginalization.” In Reconstructing Gender: A Multi-

cultural Anthology, edited by E. Disch, 248–54. Mountain View, CA: McGraw-Hill Press.

2000.

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 225 9/24/15 9:20 AM

226 bat tle, harris, donaldson, and mushtaq

Sander, Thomas and Robert Putnam. “Social Capital and Civic Engagement of Individu-

als over Age Fifty in the United States.” In Civic Engagement and the Baby-Boomer

Generation: Research, Policy, and Practice Perspectives, edited by L. B. Wilson and S.

P. Simson, 21–39. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press, Inc., 2006.

Singh, Anneliese A., Y. Barry Chung, and Jennifer K. Dean. “Acculturation Level and Inter-

nalized Homophobia of Asian American Lesbian and Bisexual Women: An Exploratory

Analysis.” Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling 1, no. 2 (2007): 3–19.

Skocpol, Theda, and Morris Fiorina. “Making Sense of the Civic Engagement Debate.” In

Civic Engagement in American Democracy, edited by T. Skocpol and M. P. Fiorina, 1–23.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press, 1999.

Tajfel, Henri and John Turner. “The Social Iidentity Theory of Inter-Group Behavior.” In

Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by S. Worchel and L. W. Austin. Chicago:

Nelson-Hall, 1986.

Uba, Laura. Asian Americans. New York: Guilford Press, 1994.

Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady. Voice and Equality. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Ward, Elijah G. “Homophobia, Hypermasculinity, and the US Black Church.” Culture,

Health and Sexuality 7, no. 5 (2005): 493–504.

Wei, William. The Asian American Movement. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.

Wong, Janelle. Asian American Political Participation. New York: Russell Sage Founda-

tion, 2011.

Xu, Jun. “The Political Behavior of Asian Americans: A Theoretical Approach.” Journal of

Political and Military Sociology 30, no. 1 (2002): 71–89.

Yuval-Davis, Nira. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40,

no. 3 (2006): 197–214.

This content downloaded from

129.1.59.224 on Sun, 12 May 2019 19:29:05 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WGFC 3_2 text.indd 226 9/24/15 9:20 AM

You might also like

- Sociology ProjectDocument14 pagesSociology ProjectRaghavendra NadgaudaNo ratings yet

- Grandmother, Gran, Gangsta Granny: Semiotic Representations of GrandmotherhoodiDocument24 pagesGrandmother, Gran, Gangsta Granny: Semiotic Representations of GrandmotherhoodiCláudia Ponciano100% (1)

- This Content Downloaded From 132.174.253.206 On Wed, 09 Feb 2022 02:10:12 UTCDocument54 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 132.174.253.206 On Wed, 09 Feb 2022 02:10:12 UTCFrancisco Reyes-VázquezNo ratings yet

- Reflective Log 1 Gender and Sexual IdentityDocument10 pagesReflective Log 1 Gender and Sexual IdentityMuhammad MujtabaNo ratings yet

- (Sexual) Minority Report: A Survey of Student Attitudes Regarding The Social and Cultural Environment For Sexual MinoritiesDocument34 pages(Sexual) Minority Report: A Survey of Student Attitudes Regarding The Social and Cultural Environment For Sexual MinoritiesEthanNo ratings yet

- SubcultureDocument4 pagesSubculture609530657No ratings yet

- Gender Conformity in Migrant Puerto RicanDocument21 pagesGender Conformity in Migrant Puerto RicanAlexa PagánNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 95.168.118.0 On Tue, 16 Feb 2021 10:40:50 UTCDocument23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 95.168.118.0 On Tue, 16 Feb 2021 10:40:50 UTCrenkovikiNo ratings yet

- Eso 14 em PDFDocument5 pagesEso 14 em PDFFirdosh KhanNo ratings yet

- 2003 Race Racism and Discrimination With Cybelle Fox Social Psycholgy QuarterlyDocument15 pages2003 Race Racism and Discrimination With Cybelle Fox Social Psycholgy QuarterlyKeturah aNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Gender Roles and Patriarchy in Indian Perspective: StructureDocument23 pagesUnit 2 Gender Roles and Patriarchy in Indian Perspective: StructureVarsha 왈사 RayNo ratings yet

- 3 s2.0 B0080430767039991 MainDocument5 pages3 s2.0 B0080430767039991 MainALINA DONIGA .No ratings yet

- Culture and Inequality Identity, Ideology, and Difference in Postascriptive SocietyDocument19 pagesCulture and Inequality Identity, Ideology, and Difference in Postascriptive SocietyAgastaya ThapaNo ratings yet

- Ender Identities and The Search For New Spaces: Abdulrazak Gurnah's ParadiseDocument9 pagesEnder Identities and The Search For New Spaces: Abdulrazak Gurnah's ParadiseHarish KarthikNo ratings yet

- Cultural Expressions Signal Social ClassDocument29 pagesCultural Expressions Signal Social ClassCrislyn AbayabayNo ratings yet

- BED-04Sem-Hariharan-GENDER SCHOOL SOCIETYDocument42 pagesBED-04Sem-Hariharan-GENDER SCHOOL SOCIETYAjendra PNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 173.199.117.44 On Thu, 09 Sep 2021 19:41:01 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 173.199.117.44 On Thu, 09 Sep 2021 19:41:01 UTCVanessa GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Diskriminasi 3Document15 pagesJurnal Diskriminasi 3Laras etaniaNo ratings yet

- Devon Ferreira 204519344 Final Assignment: Long EssayDocument18 pagesDevon Ferreira 204519344 Final Assignment: Long Essayubiscuit100% (2)

- 1535 5674 2 PBDocument16 pages1535 5674 2 PBneyas uddinNo ratings yet

- Bonilla Silva - HabitusDocument26 pagesBonilla Silva - HabitusjeromedentNo ratings yet

- Risman Gender As A Social StructureDocument23 pagesRisman Gender As A Social StructurepackulNo ratings yet

- Lorber ShiftingParadigmsChallengingpdfDocument7 pagesLorber ShiftingParadigmsChallengingpdfВероніка ЯблонськаNo ratings yet

- StockettDocument14 pagesStockettAlessia FrassaniNo ratings yet

- Result - 11 - 29 - 2023, 10 - 11 - 34 PMDocument7 pagesResult - 11 - 29 - 2023, 10 - 11 - 34 PMRaghavendra NadgaudaNo ratings yet

- Gender & SocietyDocument17 pagesGender & SocietyMushmallow Blue100% (1)

- Caste, Class and GenderDocument30 pagesCaste, Class and GenderVipulShukla83% (6)

- Exploring The Hate Language: An Analysis of Discourses Against The LGBTQIA+ CommunityDocument10 pagesExploring The Hate Language: An Analysis of Discourses Against The LGBTQIA+ CommunityPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 196.200.131.104 On Sat, 16 Oct 2021 09:30:03 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 196.200.131.104 On Sat, 16 Oct 2021 09:30:03 UTCNasr-edineOuahaniNo ratings yet

- Stets GenderControlInteraction 1996Document29 pagesStets GenderControlInteraction 1996TEZPURIAN SHANKAR 06091999No ratings yet

- 33Document22 pages33Raissa Halili SoyangcoNo ratings yet

- Jstor 1Document31 pagesJstor 1Pushp SharmaNo ratings yet

- Gender Socialization and Identity Theory PDFDocument23 pagesGender Socialization and Identity Theory PDFSohailNo ratings yet

- Genealogy 06 00092Document12 pagesGenealogy 06 00092Abdullah Al MashoodNo ratings yet

- A Healthy Black Identity Transracial Adoption (The Blind Side)Document21 pagesA Healthy Black Identity Transracial Adoption (The Blind Side)picocol767No ratings yet

- Gender and SocietyDocument6 pagesGender and SocietybadiabhiNo ratings yet

- Creating Inclusive Identity Narratives Through ParDocument32 pagesCreating Inclusive Identity Narratives Through ParRuska EpadzeNo ratings yet

- GenderRolesandGenderDifferencesDilemmaDocument6 pagesGenderRolesandGenderDifferencesDilemmaCleardy ZendonNo ratings yet

- Socialization and Gender Roles Within The FamilyDocument8 pagesSocialization and Gender Roles Within The FamilyTamiris SantosNo ratings yet

- Sociology ProjectDocument20 pagesSociology ProjectBhanupratap Singh Shekhawat0% (1)

- Social Classes Reflected by The Main Characters in Kevin Kwan's "Crazy Rich Asians" NovelDocument15 pagesSocial Classes Reflected by The Main Characters in Kevin Kwan's "Crazy Rich Asians" NovelNur Azizah RahmanNo ratings yet

- Gender Introduction: Biological and Social PerspectivesDocument7 pagesGender Introduction: Biological and Social PerspectivesHeba LotfyNo ratings yet

- Gender Barriers For Women in Construction of Cyber-Self: A Study in Pakistani Socio-Cultural ContextDocument15 pagesGender Barriers For Women in Construction of Cyber-Self: A Study in Pakistani Socio-Cultural ContextApplied Psychology Review (APR)No ratings yet

- Sociological Perspectives On Socialization: August 2018Document23 pagesSociological Perspectives On Socialization: August 2018Bokou KhalfaNo ratings yet

- KoropeckyjCox SinglesSocietyScience 2005Document8 pagesKoropeckyjCox SinglesSocietyScience 2005sanjayrajanand18No ratings yet

- Gender Discourse Without Society and ScriptureDocument4 pagesGender Discourse Without Society and ScriptureEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Sex RolesDocument6 pagesSex Rolesdznb44No ratings yet

- Why Intersectionality Is Important in Sexuality Studies: University Affiliation Student's NameDocument10 pagesWhy Intersectionality Is Important in Sexuality Studies: University Affiliation Student's NameDamn HommieNo ratings yet

- Identity As Resistance: Identity Formation at The Intersection of Race, Gender Identity, and Sexual OrientationDocument17 pagesIdentity As Resistance: Identity Formation at The Intersection of Race, Gender Identity, and Sexual OrientationMuthiara SNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Perspectives On GenderDocument14 pagesConceptual Perspectives On GenderYashasviNo ratings yet

- Gender, Ethnicity and Race: A Study of Social ConstructsDocument22 pagesGender, Ethnicity and Race: A Study of Social Constructsmatrixtrinity100% (1)

- A Genealogy of Dependency - Fraser and GordonDocument29 pagesA Genealogy of Dependency - Fraser and GordonKolya CNo ratings yet

- Michelle Mejia-Benitez Synthesis PaperDocument29 pagesMichelle Mejia-Benitez Synthesis Paperapi-615817383No ratings yet

- From Sex Roles To Gendered Institutions. AckerDocument6 pagesFrom Sex Roles To Gendered Institutions. AckerMiguel Angel AmbrocioNo ratings yet

- Reading B (1-3)Document1 pageReading B (1-3)Martha Glorie Manalo WallisNo ratings yet

- Draft Essay With ConceptsDocument11 pagesDraft Essay With ConceptsAnthony MulengaNo ratings yet

- Social Construction of GenderDocument7 pagesSocial Construction of GenderOptimistic Pashteen100% (2)

- Gender and Society-SageDocument23 pagesGender and Society-SagetentendcNo ratings yet

- Cultura - de - Genero - La - Brecha - Ideologica - Entre - Hombr en-USDocument13 pagesCultura - de - Genero - La - Brecha - Ideologica - Entre - Hombr en-UScelestial365No ratings yet

- The Gag Reflex: Disgust Rhetoric and Gay Rights in American PoliticsDocument23 pagesThe Gag Reflex: Disgust Rhetoric and Gay Rights in American PoliticsJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Correlates of Suicide Ideation Among LGBT NebraskansDocument21 pagesCorrelates of Suicide Ideation Among LGBT NebraskansJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Examining Internal Traumatic Gay Men's Syndrome (ITGMS) and Queer Indigenous CitizenshipDocument6 pagesExamining Internal Traumatic Gay Men's Syndrome (ITGMS) and Queer Indigenous CitizenshipJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Politicizing Abjection: in The Manner of A Prologue For The Articulation of AIDS Latino Queer IdentitiesDocument9 pagesPoliticizing Abjection: in The Manner of A Prologue For The Articulation of AIDS Latino Queer IdentitiesJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Becoming Queerly Responsive: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy For Black and Latino Urban Queer YouthDocument27 pagesBecoming Queerly Responsive: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy For Black and Latino Urban Queer YouthJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory and Native Studies: The Heteronormativity of Settler ColonialismDocument29 pagesQueer Theory and Native Studies: The Heteronormativity of Settler ColonialismJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Eliding Trans Latino/a Queer Experience in U.S. LGBT History: José Sarria and Sylvia Rivera ReexaminedDocument24 pagesEliding Trans Latino/a Queer Experience in U.S. LGBT History: José Sarria and Sylvia Rivera ReexaminedJo Wilson100% (1)

- Scholars Explore Identities of Queer Latinos During Daylong SymposiumDocument3 pagesScholars Explore Identities of Queer Latinos During Daylong SymposiumJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Finding Comunidad: Latino Gay/Queer Students' Co-Curricular Experiences of Empowerment and Marginality at A Public UniversityDocument122 pagesFinding Comunidad: Latino Gay/Queer Students' Co-Curricular Experiences of Empowerment and Marginality at A Public UniversityJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Intensiones: Tensions in Queer Agency and Activism in Latino AméricaDocument14 pagesIntensiones: Tensions in Queer Agency and Activism in Latino AméricaJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Disclosure, Life Experiences, and Social Relations of Sexuality: A New Generation of US Latino Queer MenDocument268 pagesDisclosure, Life Experiences, and Social Relations of Sexuality: A New Generation of US Latino Queer MenJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- What Queer Latinos Are Saying About The Orlando ShootingDocument3 pagesWhat Queer Latinos Are Saying About The Orlando ShootingJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Black & QTPOC Artists: (Re) Claiming SpaceDocument3 pagesBlack & QTPOC Artists: (Re) Claiming SpaceJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Mapeando La Cultura Kruda: Hip-Hop, Punk Rock y Performances Queer Latino ContemporáneoDocument92 pagesMapeando La Cultura Kruda: Hip-Hop, Punk Rock y Performances Queer Latino ContemporáneoJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Social Challenges Faced by Queer Latino College Men: Navigating Negative Responses To Coming Out in A Double Minority Sample of Emerging AdultsDocument11 pagesSocial Challenges Faced by Queer Latino College Men: Navigating Negative Responses To Coming Out in A Double Minority Sample of Emerging AdultsJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- The Missing Colors of The Rainbow: Black Queer ResistanceDocument22 pagesThe Missing Colors of The Rainbow: Black Queer ResistanceJo Wilson100% (1)

- Ruminations On Lo Sucio As A Latino Queer AnalyticDocument13 pagesRuminations On Lo Sucio As A Latino Queer AnalyticJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Where Is My Place?: Queer and Transgender Students of Color Experiences in Cultural Centers at A Predominantly White UniversityDocument138 pagesWhere Is My Place?: Queer and Transgender Students of Color Experiences in Cultural Centers at A Predominantly White UniversityJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Queer and Trans Students of Color Need Your SupportDocument3 pagesQueer and Trans Students of Color Need Your SupportJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarsinha Speaks With Syrus Marcus WareDocument1 pageLeah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarsinha Speaks With Syrus Marcus WareJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Marriage Equality and The African American Case: Intersections of Race and LGBT SexualityDocument8 pagesMarriage Equality and The African American Case: Intersections of Race and LGBT SexualityJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- There Are Brown Ways of Being QueerDocument3 pagesThere Are Brown Ways of Being QueerJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Influence of Stigma and Medical Mistrust On Engagement in Routine Healthcare Among Black Women Who Have Sex With WomenDocument7 pagesUnderstanding The Influence of Stigma and Medical Mistrust On Engagement in Routine Healthcare Among Black Women Who Have Sex With WomenJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Encouraged or Weeded Out: Perspectives of Students of Color in The STEM Disciplines On Faculty InteractionsDocument18 pagesEncouraged or Weeded Out: Perspectives of Students of Color in The STEM Disciplines On Faculty InteractionsJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- "Quadruple Consciousness": A Literature Review and New Theoretical Consideration For Understanding The Experiences of Black Gay and Bisexual College Men at Predominantly White InstitutionsDocument14 pages"Quadruple Consciousness": A Literature Review and New Theoretical Consideration For Understanding The Experiences of Black Gay and Bisexual College Men at Predominantly White InstitutionsJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Measuring Multiple Minority Stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions ScaleDocument12 pagesMeasuring Multiple Minority Stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions ScaleJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- LGB of Color and White Individuals' Perceptions of Heterosexist Stigma, Internalized Homophobia, and Outness: Comparisons of Levels and LinksDocument28 pagesLGB of Color and White Individuals' Perceptions of Heterosexist Stigma, Internalized Homophobia, and Outness: Comparisons of Levels and LinksJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Queer Solidarities: New Activisms Erupting at The Intersection of Structural Precarity and Radical MisrecognitionDocument23 pagesQueer Solidarities: New Activisms Erupting at The Intersection of Structural Precarity and Radical MisrecognitionJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Feeling Fear, Feeling Queer: The Peril and Potential of Queer TerrorDocument8 pagesFeeling Fear, Feeling Queer: The Peril and Potential of Queer TerrorJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Prelim Exam in Purposive Communication (Crim1b)Document4 pagesPrelim Exam in Purposive Communication (Crim1b)Harlequin ManucumNo ratings yet

- Educ 456 TpaDocument4 pagesEduc 456 Tpaashleyb12No ratings yet

- Methods of ResearchDocument18 pagesMethods of ResearchCalvin SeraficaNo ratings yet

- Performance and Compensation Management Case StudyDocument3 pagesPerformance and Compensation Management Case StudyMd. Khairul BasharNo ratings yet

- Robert KatzDocument2 pagesRobert KatzMuthu KumarNo ratings yet

- The Satir Change ModelDocument5 pagesThe Satir Change ModelYufi Mustofa100% (2)

- Final Syllabus Forensic Psychology Spring 2016Document6 pagesFinal Syllabus Forensic Psychology Spring 2016Karla PereraNo ratings yet

- Famous Psychologists and Their ContributionsDocument43 pagesFamous Psychologists and Their ContributionsRach ArmentonNo ratings yet

- Mind PowerDocument282 pagesMind PowerPrince McGershonNo ratings yet

- How To Improve Effective Communication in Verbal CommunicationDocument4 pagesHow To Improve Effective Communication in Verbal CommunicationVanessa abadNo ratings yet

- 9 - Lesson 4Document4 pages9 - Lesson 4Lapuz John Nikko R.100% (2)

- How Employee Wellbeing Shapes Workplace CulturesDocument3 pagesHow Employee Wellbeing Shapes Workplace CulturesKlinik SamaraNo ratings yet

- Software Project Team Coordination and Communication IssuesDocument39 pagesSoftware Project Team Coordination and Communication IssuesHusnainNo ratings yet

- Leadership TheoriesDocument11 pagesLeadership TheoriesDom MartinezNo ratings yet

- OB Cheat SheetDocument8 pagesOB Cheat SheetsxywangNo ratings yet

- ApqhsnsiDocument11 pagesApqhsnsiRozak HakikiNo ratings yet

- The Western and Eastern Concepts of SelfDocument12 pagesThe Western and Eastern Concepts of SelfNiña Lee Magdale GalarpeNo ratings yet

- Performance Management OverviewDocument21 pagesPerformance Management OverviewChris Jay LatibanNo ratings yet

- EXCUSITISDocument2 pagesEXCUSITISRohit KamalakarNo ratings yet

- ADOS 2 - Revised AlgorithmDocument2 pagesADOS 2 - Revised AlgorithmGoropad50% (2)

- Successful Transition To KindergartenDocument8 pagesSuccessful Transition To KindergartenMilena Mina MilovanovicNo ratings yet

- Educational Theories of GMRCDocument11 pagesEducational Theories of GMRCPatricia Mariz LorinaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Form 2Document69 pagesEvaluation Form 2Radee King CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Karen HorneyDocument15 pagesKaren Horneyphotocopyshop. rwuNo ratings yet

- Sleep Diary: How To Use The National Sleep Foundation Sleep DiaryDocument4 pagesSleep Diary: How To Use The National Sleep Foundation Sleep DiaryLeon MakNo ratings yet

- Case Report of PatientDocument25 pagesCase Report of PatientMaria Qibtia100% (2)

- PPG 215 Meeting Student NeedsDocument24 pagesPPG 215 Meeting Student NeedsmrajisNo ratings yet

- Psychological Empowerment and Commitment Rama KrishnaDocument16 pagesPsychological Empowerment and Commitment Rama Krishnavsource.hcm100% (4)

- Notice Ret Result-July 2023Document2 pagesNotice Ret Result-July 2023webiisNo ratings yet

- Survey ResultDocument6 pagesSurvey ResultAbdul RahimNo ratings yet