Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Portugal Vs India

Uploaded by

Tanay MandotCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Portugal Vs India

Uploaded by

Tanay MandotCopyright:

Available Formats

Summaries of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders of the International Court of Justice

Not an official document

CASE CONCERNING RHGHT OF PASSAGE OVER INDIAN TERRITORY

(PRELIMINARY OBJECTIONS)

Judgment of 26 Novemlber 1957

The case concerning right of passage over Indian territory The Government of India for its part raised six Preliminary

(hliminary Objections) between Portugal and India was Objections to the jurisdiction of the Court which were based

submitted by Application CIE the Portuguese Government on the following grounds:

requesting the Court to recognize and declare that Portugal The First Preliminary Objection was to the effect that a

was the holder or beneficiary of a right of passage ktween its condition in the Portuguese Declaration of December 19th,

temtory of Damgo (littoral Damgo) and its er~clavesof Dadra 1955, accepting the jurisdiction of the Court resewed for that

and Nagar-Aveli and betwee:rt each of the 1at.terand that this Goverr~ment"the right to exclude from the scope of the

right comprises the faculty of transit for persons .and goods, present Declaration at any time during its validity any given

including armed forces, witllout restrictions or difficulties categoly or categories of disputes by notifying the Secretary-

and in the manner and to the extent required by the effective General of the United Nations and with effect from the

exercise of Portuguese soven:ignty in the said territories, that moment of such notification" and was incompatible with the

India has prevented and conti.nuesto prevent the exercise of object and purpose of the Optional Clause, with the result

the right in question, thus committing an offence t:othe detri- that the Declaration of Acceptance was invalid.

ment of Portuguese Sovereilpty over the er~clavesand vio-

lating its international obligiitions and to adjudge that India The Second Preliminary Objection was ba&d on the alle-

should put an immediate end to this situation by allow- gation that the Pbrtuguese Application of Ikcember 22nd,

ing Portugal to exercise the right of passage thus claimed. 1955, was filed before a copy of the Declaration of Portugal

The Application expressly referred to Article 36, paragraph accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court could be

2, of the Statute and to the l[)eclarations by which Pbrtugal transmitted to other F'arties to the Statute by.the Secretary-

and India have accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the General in compliance with Article 36, paxagraph 4, of the

Court. Statute. The filing of the Application had thus violated the

Continued on next page

equality, mutuality and reciprocity to which India was enti- the Judgment statements of their dissenting opinions. M.

tled under the Optional Clause and under the express condi- Fernandes, Judge ad hoc, concurred in the dissenting opin-

tion of reciprocity contained in its Declaration of February ion of Judge Klaestad and Mr. Chagla, Judge ad hoc,

28th, 1940, accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the appended to the Judgment a statement of his dissenting

Court. opinion.

The Third Preliminary Objection was based on the

absence, prior to the filing of the Application, of diplomatic

negotiations which would have made it possilble to define the

subject matter of the claim.

The Fourth Preliminary Objection requested the Court to

declare that since India had ignored the Portuguese Declara- With regard to the First Preliminary Objection to the effect

tion before the Application was filed, India had been unable that the Portuguese lDeclaration was invalid for the reason

to avail itself on the basis of reciprocity of the condition in the that the condition enabling Portugal to exclude at any time

Portuguese Declaration enabling it to exclude:from the juris- from the scope of that Declaration any given categories of

diction of the Court the dispute which was the subject malter disputes by mere notification to the Secretary-General, the

of the Application. Court said that the words used in the condition, construed in

The Fi'h Preliminary Objection was based on the reserva- their ordinary sense, meant simply that a notification under

tion in the Indian Declaration of Acceptance 'which excludes that condition applied only to disputes brought before the

from the jurisdiction of the Court disputes in regard to ques- Court afer the date cbf the notification. No retroactive effect

tions which by international law fall exclusi.vely within the could thus be imputed to such a notification. In this connec-

jurisdiction of the Government of India. That Government tion the Court refemi to the principle which it had laid down

asserted that the facts and the legal considerations adduced in the Nottebohm case in the following words: "An extrinsic

before the Court did not permit the conclusiori that there was fact such as the lapse of the Declaration by reason of the

a reasonably arguable case for the contention that the subject expiry of the period or of denunciation cannot deprive the

matter of the dispute was outside its domesticjurisdiction. Court of the jurisdiction already established." The Court

added that this principle applied both to total denunciation,

Finally, in The Sixth Preliminary Objectio.n,the Govern- and to partial denunciation as contemplated in the impugned

ment of India contended that the Court was without jurisdic- condition of the Portuguese Declaration.

tion on the ground that India's Declaration of Acceptance

was limited to "disputes arising after Febnlary 5 t h 1930 India having contended that this condition had introduced

with regard to situations or facts subsequerlt to the same into the Declaration al degree of uncertainty as to reciprocal

date." The Government of India argued: first, lhat the dispute rights and obligations which deprived the Acceptance of the

submitted to the Court by Portugal did not arise after Febru- compulsory jurisdiction of the Court of all practical value,

ary 5th, 1930and, secondly, that in any case, it was a dispute the Court held that as :kclarations and their alterations made

with regard to situations and facts prior to that date. under Article 36 of the Statute had to be deposited with the

The Government of Portugal had added to its Submissions Secretary-General it followed that, when a case was submit-

a statement requesting the Court to recall to the Parties the ted to the Court, it was always possible to ascertain what

universally admitted principle that they should facilitate the were, at that moment, the reciprocal obligations of the Par-

accomplishment of the task of the Court by abstaining from ties in accordance with their respective Declarations.

any measure capable of exercising a prejudicial effect in Although it was true that during the interval between the date

regard to the execution of its decision or which might bring of the notification to the Secretary-Generaland its receipt by

about either an aggravation or an extension of the dispute. the Parties to the Statute there might exist some element of

The Court did not consider that in the circumstances of the uncertainty, such uncertainty was inherent in the operation of

present case it should comply with this request of the Gov- the system of the Optional Clause and did not affect the valid-

ernment of Portugal. ity of the condition contained in the Portuguese Declaration.

The Court noted that with regard to any degree of uncertainty

In its Judgment, the Court rejected the Fint and the Sec- resulting from the right of Portugal to avail itself at any time

ond Preliminary Objections by fourteen votes to three, the of the Condition in its Acceptance, the position was substan-

Third by sixteen votes to one and the Fourth by fifteen votes tially the same as that created by the right claimed by many

to two. By thirteen votes to four it joined the Fifth Objection Signatories of the Optional Clause, including India, to termi-

to the merits and by fifteen votes to two joined the Sixth nate their Declarations of Acceptance by simple notification

Objection to the merits. Finally, it declated that the proceed- without notice. It recalled that India had done so on January

ings on the merits were resumed and fixed as follows the 7th, 1956, when it notified the Secretary-General of the

time-limits for the rest of the proceedings: denunciation of its 1)eclaration of February 28th. 1940

For the filing of the Counter-Memorial of hdia, February (relied upon by Portugal in its Application), for which it

25th, 1958;for the filing of the Portuguese Reply, May 25th. simultaneously substituted a new Declaration incorporating

1958;for the filing of the Indian Rejoinder, July 25th, 1958. reservations which wt!re absent from its previous Declara-

tion. By doing so, India achieved in substance the object of

the condition in Portugal's Declaration.

Moreover, in the view of the Court, there was no essential

difference with regard to the degree of uncertainty between a

situation resulting frorn right of total denunciation and that

Judge Kojevnikov stated that he could not concur either in resulting from the condition in the Portuguese Declaration

the operative clause or in the reasoning of the Judgment which left open the poaisibility of a partial denunciation. The

because, in his opinion, the Court should, at the present stage Court further held that it was not possible to admit as a rele-

of the proceedings, have sustained one or indeed more of the vant differentiating factor that while in the case of total

Preliminary Objections. denunciation the denouncing State could no longer invoke

Vice-President Badawi and Judge Klaestad appended to any rights accruing under its Declaration, in the case of a par-

tial denunciation under the tetms of the Portuiguese Declara- had transmitted a copy thereof to the Parties. The Court held

tion Portugal could otherwise continue to claim the benefits that the declarant State was concerned only with the deposit

of its Acceptance. The principle of reciprocity made it possi- of its Declaration with the Secretary-General and was not

ble for other States including :Indiato invoke against Portugal concerned with the duty of the Secretary-Generalor the man-

all the rights which it might thus continue to claim. ner of its fulfilment. The Court could not read into the

A third reason for the alleged invalidity of the 1)ortuguese Optional Clause the requirement that an interval should

Condition was that it offended against the basic principle of elapse subsequent to the deposit of the Declaration. Any such

reciprocity underlying the Optional Clause, inasmuch as it requirement would introduce an element of uncertainty into

claimed for Portugal a right which in effect was denied to the operation of the Optional Clause system.

other Signatories whose Declarations did not contain a simi- As India had not specified what actual light which she

lar condition. The Court was unable to accept this conten- derived from the Statute and the Declaration had been

tion. It held that if the positic~nof the Parties as ~egardsthe adversely affected by the manner of the filing of the Applica-

exercise of their rights was; in any way affected by the tion, the Court was unable to discover what right had in fact

unavoidable interval betweelm the receipt by the Secretary- thus been violated.

General of the appropriate notification and its receipt or by Having arrived at the conclusion that the Application was

the other Signatories, that delay operated equally in favour of filed in a manner which was neither contrary to the Statute

or against all Signatories of the Optional Claiise. nor in violation of any right of India, the Court dismissed the

The Court also refused to a.ccept the view that the Condi- Second Preliminary Objection.

tion in the Portuguese Declaration was inconsistent with the

principle of reciprocity inasmuch as it rendered inoperative

that part of paragraph 2 of Article 36 which refers to the

acceptance of the Optional Clause in rel.ation to States

acc&ting "the same obligationw.It was noi: necessary that The Court then dealt with the Fourth Preliminary Objec-

"the same obligation" should be irrevocabl:~defined at the tion which was also concerned with the manner in which the

time of acceptance for the entire period of its duration; that Application was filed.

expression simply meant no more than that, as between the

States adhering to the Optional Clause, each and all of them India,contended that having regard to the rnanner in which

were bound by such identicel obligations as might exist at the Application was filed, it had been unable to avail itself on

any time during which the acceptance was mutually binding. the basis of reciprocity of the condition in the Portuguese

Declaration and to exclude from the jurisdiction of the Court

As the Court found that the condition in the Portuguese the dispute which was the subject matter of the Application.

Declaration was not inconsistent with the Statute, it was not The Court merely recalled what it had said in dealing with the

necessary for it to consider the position whether, if it were Second Objection, in particular that the Statute did not pre-

invalid, its invalidity woul~rlaffect the D'eclaration as a scribe 'my interval between the deposit of a Declaration of

whole. Accepmce and the filing of an Application.

The Court then dealt with the Second Objection based on

the allegation that as the Application was filtd before Portu- On the Third Preliminary Objection which invoked the

gal's acceptance of the Cour1:'s jurisdiction could be notified absence of diplomatic negotiations prior to the filing of the

by the Secretary-General to 'the other Signatories, the filing Application, the Court held that a substantial part of the

of the Application violated hie equality, mu1:uality and reci- exchanges or views between the Parties prior to the filing of

procity to which India was entitled under the Optional Clause the Application was devoted to the question of access to the

and under the express condition contained in its Declaration. enclaves, that the correspondence and notes laid before the

The Court noted that two questions had to be considered: Court revealed the repeated complaints of Portugal on

first, in filing its Application on the day following the deposit account of denial of transit facilities, and that the correspon-

of its Declaration of Acceptance, did Portugat act in a manner dence :showed that negotiations had reached a deadlock.

contrary to the Statute; second, if not, did it thereby violate Assuming that Article 36, paragraph 2, of the Statute by

any right of India under the Statute or under its Dt:claration. referring to legal disputes, did require a definition of the dis-

India maintained that before filing its Application Portugal pute through negotiations, the condition had been complied

ought to have allowed such pe:riod to elapse as would reason- with.

ably have permitted other Signatories of the Optional Clause

to receive from the Secretary-Generalnotification of the Por-

tuguese Declaration.

The Court was unable to accept that contention. The con-

tractual relation between the Parties and the compulsory In its; Fifrh Objection, India relied on a reservation in its

jurisdiction of the Court res~~lting therefrom are established own Declaration of Acceptance which excludes from the

"ipsofacto and without speciial agreement" by the fact of the jurisdiction of the Court disputes with regard to questions

making of the Declaration. A. State accepting the jurisdiction which by international law fall exclusively within the juris-

of the Court must expect that an Application may be filed diction of the Government of India, and asserted that the

against it before the Court tly a new declari~ntState on the facts and the legal considerations adduced before the Court

same day on which that Stale deposits its Acceptance with did not permit the conclusion that there was a reasonably

the Secretary-General. arguable case for the contention that the subject matter of the

India had contended that iicceptance of the Court's juris- dispute was outside the exclusive domestic jurisdiction of

diction became effective only when the Secretary-General India.

The Court noted that the facts on which the Submissions of Finally, in dealing with the Sixth Objection based on the

India were based were not admitted by Portugal and that elu- reservation ratione .temporis in the Indian Declaration limit-

cidation of those facts and their legal cons.equences would ing the Declaration to disputes arising after February 5th,

involve an examination of the practice of the British. Indian 1930, with regard I:Osituations or facts subsequent to that

and Portuguese authorities in the matter of the right of pas- date, the Court noted that to ascertain the date on which the

sage, in particular to determine whether this practice showed dispute had arisen it was necessary to examine whether or not

that the Parties had envisaged this right as a question which the dispute was only a continuation of a dispute on the right

according to international law was exclusively within the of passage which had arisen before 1930. The Court having

jurisdiction of the territorial sovereign. All these and similar heard conflicting arguments regarding the nature of the pas-

questions could not be examined at this pireliminary stage sage formerly exercised was not in a position to determine

without prejudging the merits. Accordirrgly, the Court these two questions at this stage.

decided to join the Fifth Objection to the merits. Nor did-the COUIZhave atpresent sufficient evidence to

enable it to pronounce on the question whether the dispute

concerned situation!; or facts prior to 1930. Accordingly, it

joined the Sixth Preliminary Objection to the merits.

You might also like

- Supreme Court rules against retroactive application of time-bar ruleDocument1 pageSupreme Court rules against retroactive application of time-bar rulePouǝllǝ ɐlʎssɐ100% (2)

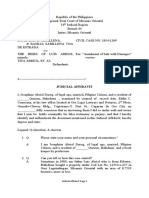

- Republic of the Philippines Regional Trial Court AffidavitDocument6 pagesRepublic of the Philippines Regional Trial Court AffidavitBPH MaramagNo ratings yet

- Loan ruled personal despite business use based on promissory noteDocument1 pageLoan ruled personal despite business use based on promissory noteattyalanNo ratings yet

- Manzanaris Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesManzanaris Vs PeopleJuan DoeNo ratings yet

- Salmingo vs. RubicaDocument2 pagesSalmingo vs. RubicalabellejolieNo ratings yet

- Corporate Law Case Digest: Tayag V. Benguet: Torres vs. CA - GR 120138, Sept. 5, 1997Document8 pagesCorporate Law Case Digest: Tayag V. Benguet: Torres vs. CA - GR 120138, Sept. 5, 1997PingLomaadEdulanNo ratings yet

- Sta. Rosa Realty Dev Corp vs. AmanteDocument1 pageSta. Rosa Realty Dev Corp vs. AmanteMichael JosephNo ratings yet

- Noceda Vs EscobarDocument2 pagesNoceda Vs EscobarKar EnNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts: CADASTRAL PROCEEDINGS (READ: PRDRL, Agcaoili, 2018 Ed., Pp. 350-368)Document14 pagesBasic Concepts: CADASTRAL PROCEEDINGS (READ: PRDRL, Agcaoili, 2018 Ed., Pp. 350-368)Hermay BanarioNo ratings yet

- Adultery Laws Need Reform for Equality and JusticeDocument7 pagesAdultery Laws Need Reform for Equality and JusticeMonish NagarNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Cadeliña Vs CadizDocument9 pagesHeirs of Cadeliña Vs CadizMary Fatima Tolibas BerongoyNo ratings yet

- DBP Vs Acting Register of Deeds of Nueva EcijaDocument6 pagesDBP Vs Acting Register of Deeds of Nueva EcijaLyceum LawlibraryNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank vs. Intermediate Appellate Court: - First DivisionDocument6 pagesPhilippine National Bank vs. Intermediate Appellate Court: - First DivisionDorky DorkyNo ratings yet

- Office of The Ombudsman vs. Uldarico P. Andutan, JRDocument2 pagesOffice of The Ombudsman vs. Uldarico P. Andutan, JRRonald T. LizardoNo ratings yet

- NCMB Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration ProceedingsDocument12 pagesNCMB Procedural Guidelines in The Conduct of Voluntary Arbitration ProceedingskringjoyNo ratings yet

- Verbena D. Balagat PNB V PNB EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATIONDocument2 pagesVerbena D. Balagat PNB V PNB EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATIONMae Clare BendoNo ratings yet

- Midterm Answers With ExplanationDocument10 pagesMidterm Answers With ExplanationJyNo ratings yet

- Supapo Vs de Jesus 756 Scra 211Document20 pagesSupapo Vs de Jesus 756 Scra 211JennyNo ratings yet

- Collective Bargaining Agreement SummaryDocument14 pagesCollective Bargaining Agreement SummaryBriar RoseNo ratings yet

- De Castro VSDocument3 pagesDe Castro VSSam MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Insular Bank of Asia and America v. Borromeo (1978) Pamisa EH202Document3 pagesInsular Bank of Asia and America v. Borromeo (1978) Pamisa EH202Hyules PamisaNo ratings yet

- SABANDAL vs. HON. FELIPE S. TONGCO G.R. No. 124498 October 5, 2001Document2 pagesSABANDAL vs. HON. FELIPE S. TONGCO G.R. No. 124498 October 5, 2001pawsmason100% (1)

- Lapez - Partnership CasesDocument3 pagesLapez - Partnership CasesAnonymous jUM6bMUuRNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs HendersonDocument6 pagesCIR Vs Hendersonanon_614984256No ratings yet

- Chapter 1. Requisites of MarriageDocument36 pagesChapter 1. Requisites of MarriageWagun Lobbangon BasungitNo ratings yet

- LTD Case Digests Mas CompleteDocument399 pagesLTD Case Digests Mas Completejerico lopezNo ratings yet

- 23 Republic v. Go PDFDocument25 pages23 Republic v. Go PDFClarinda Merle100% (1)

- Mapa Vs CADocument6 pagesMapa Vs CAIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- Land Titles and Deeds CasesDocument82 pagesLand Titles and Deeds CasesRail Lucep100% (1)

- Page 1 of 7Document7 pagesPage 1 of 7Aaliyah AndreaNo ratings yet

- The Corporation Code of The PhilippinesDocument42 pagesThe Corporation Code of The PhilippinesAaronNo ratings yet

- Icasiano vs. IcasianoDocument3 pagesIcasiano vs. IcasianoNash LedesmaNo ratings yet

- AM No. 02 11 10 SC PDFDocument6 pagesAM No. 02 11 10 SC PDFCherzNo ratings yet

- Alonzo Vs IACDocument1 pageAlonzo Vs IACJerome C obusanNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Yapyuco vs. Sandiganbayan and People G. R. No. 120744-46Document2 pagesCase Digest - Yapyuco vs. Sandiganbayan and People G. R. No. 120744-46Manalese, L.M.No ratings yet

- Vda. de Agatep vs. LimDocument1 pageVda. de Agatep vs. LimlchieSNo ratings yet

- ICJ Advisory Opinion On Reservations To The Genocide Convention PDFDocument33 pagesICJ Advisory Opinion On Reservations To The Genocide Convention PDFLorenzo AradaNo ratings yet

- St. Martin Funeral Homes vs. National Labor Relations CommissionDocument2 pagesSt. Martin Funeral Homes vs. National Labor Relations CommissionCali Ey100% (1)

- Heirs of Sandueta v. RoblesDocument3 pagesHeirs of Sandueta v. RoblesPaul Joshua SubaNo ratings yet

- Court upholds finality of land registration decreesDocument1 pageCourt upholds finality of land registration decreesIanLightPajaroNo ratings yet

- 07 Chu vs. National Labor Relations CommissionDocument4 pages07 Chu vs. National Labor Relations Commissionjudyrane100% (1)

- Election - Laws Memory AidDocument30 pagesElection - Laws Memory AidLeandro Baldicañas PiczonNo ratings yet

- 3 PubCorp Municipality of Candijay v. CA When Defective MunCorp BECOMES de Jure MunCorpDocument9 pages3 PubCorp Municipality of Candijay v. CA When Defective MunCorp BECOMES de Jure MunCorplouis jansenNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law, Professors Sundiang and Aquino) : Common Form of Bill of ExchangeDocument11 pagesCommercial Law, Professors Sundiang and Aquino) : Common Form of Bill of ExchangeLizzy WayNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines v. PIATCO DigestDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines v. PIATCO DigestSamantha KingNo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds ban on electro fishing in freshwaterDocument8 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court upholds ban on electro fishing in freshwaterJohn Carlo BiscochoNo ratings yet

- 106-Alliance of Democratic Free Labor Organization (ADFLO) v. Laguesma G.R. No. 108625 March 11, 1996Document8 pages106-Alliance of Democratic Free Labor Organization (ADFLO) v. Laguesma G.R. No. 108625 March 11, 1996Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Compiled Cases For Succession - EditedDocument156 pagesCompiled Cases For Succession - EditedJennica Gyrl DELFINNo ratings yet

- Valencia Vs Peralta, JR., 118 Phil 691, G.R. No. L-20864, August 23, 1963Document2 pagesValencia Vs Peralta, JR., 118 Phil 691, G.R. No. L-20864, August 23, 1963Gi NoNo ratings yet

- ESTATE OF GEORGE LITTON DigestDocument3 pagesESTATE OF GEORGE LITTON DigestPaolo BrillantesNo ratings yet

- Land Bank Vs RepublicDocument1 pageLand Bank Vs RepublicbreeH20No ratings yet

- United Pulp and Paper CoDocument1 pageUnited Pulp and Paper Coalbert agnesNo ratings yet

- Spouses Bautista Vs Sula - A.M. No. P-04-1920. August 17, 2007Document9 pagesSpouses Bautista Vs Sula - A.M. No. P-04-1920. August 17, 2007Ebbe DyNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines Versus Raul Yamon TuandoDocument1 pagePeople of The Philippines Versus Raul Yamon TuandoBourgeoisified LloydNo ratings yet

- Angeles, Paul Mikee O. 1-qDocument5 pagesAngeles, Paul Mikee O. 1-qMikee AngelesNo ratings yet

- Double Jeopardy Protection Denied for Unrelated CrimesDocument1 pageDouble Jeopardy Protection Denied for Unrelated CrimesWilliam Christian Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- De Leon v. Court of AppealsDocument5 pagesDe Leon v. Court of AppealsJM GenobañaNo ratings yet

- DBT Case LTDDocument2 pagesDBT Case LTDDanica Irish RevillaNo ratings yet

- Father Convicted of Sexually Abusing DaughterDocument12 pagesFather Convicted of Sexually Abusing DaughterHershey GabiNo ratings yet

- Case Concerning Right of Passage Over Indian Territory (Merits) Judgment of 12 April 1960Document3 pagesCase Concerning Right of Passage Over Indian Territory (Merits) Judgment of 12 April 1960Chetna RathiNo ratings yet

- TIJ - Direito de Passagem Sobre Território Indiano (1960)Document3 pagesTIJ - Direito de Passagem Sobre Território Indiano (1960)xanoca13No ratings yet

- Scholarship Names ListDocument15 pagesScholarship Names ListTanay MandotNo ratings yet

- Step 1 - Application To The NCLT: J.K. Jute Mills Co. v. M/s Surendra Trading CoDocument5 pagesStep 1 - Application To The NCLT: J.K. Jute Mills Co. v. M/s Surendra Trading CoTanay MandotNo ratings yet

- Powers and duties of appellate courtsDocument5 pagesPowers and duties of appellate courtsTanay Mandot0% (1)

- Law Office ManagementDocument5 pagesLaw Office ManagementAnonymous H1TW3YY51KNo ratings yet

- Online GRE practice tests and resourcesDocument3 pagesOnline GRE practice tests and resourcesArchit MathurNo ratings yet

- Types of BanksDocument8 pagesTypes of BanksTanay MandotNo ratings yet

- SHARES FinalpwrptDocument21 pagesSHARES FinalpwrptTanay MandotNo ratings yet

- 56 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 577, 56 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 40,871 Sheila M. Bolar v. Anthony M. Frank, Postmaster General of The United States Postal Service, 938 F.2d 377, 2d Cir. (1991)Document5 pages56 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 577, 56 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 40,871 Sheila M. Bolar v. Anthony M. Frank, Postmaster General of The United States Postal Service, 938 F.2d 377, 2d Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- RTC Appointment Special Admin Without NoticeDocument2 pagesRTC Appointment Special Admin Without Noticeggg10No ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules 30-Day Period for Appeals Begins from Receipt of Decision, Not Denial of ReconsiderationDocument3 pagesSupreme Court Rules 30-Day Period for Appeals Begins from Receipt of Decision, Not Denial of ReconsiderationPrince CayabyabNo ratings yet

- Hualde-Redin v. Royal Bank, 1st Cir. (1997)Document8 pagesHualde-Redin v. Royal Bank, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Court adjournment petitionDocument7 pagesCourt adjournment petitionPrakashNo ratings yet

- Motion For Leave To File DemurrerDocument3 pagesMotion For Leave To File DemurrerRetsacelet Nam100% (3)

- Davis Et Al v. Tanner Et Al - Document No. 10Document2 pagesDavis Et Al v. Tanner Et Al - Document No. 10Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Home Guaranty Corp. v. R-11 Builders Inc., 22 June 2011Document2 pagesHome Guaranty Corp. v. R-11 Builders Inc., 22 June 2011Mark Alvin DelizoNo ratings yet

- RTC Lacks Jurisdiction Over Case Transferred From MCTCDocument5 pagesRTC Lacks Jurisdiction Over Case Transferred From MCTCMalaya PilipinaNo ratings yet

- Cross Westchester Development Corporation v. Mario Chiulli, Anthony Chiulli, Dennis Chiulli, Linda Chiulli Dimartino, Mario Schiavone, Jeffrey I. Klein, Sleepy Hollow Motor Court, Inc., Riccardo Development Corp., Riccardo Realty Corp., Mohawk Valley Land, Ltd., and Greenburgh Mountain Estates, Ltd., Mario Chiulli, Sleepy Hollow Motor Court, Inc., Riccardo Development Corp., Riccardo Realty Corp., and Mohawk Valley Land, Ltd., 887 F.2d 431, 2d Cir. (1989)Document3 pagesCross Westchester Development Corporation v. Mario Chiulli, Anthony Chiulli, Dennis Chiulli, Linda Chiulli Dimartino, Mario Schiavone, Jeffrey I. Klein, Sleepy Hollow Motor Court, Inc., Riccardo Development Corp., Riccardo Realty Corp., Mohawk Valley Land, Ltd., and Greenburgh Mountain Estates, Ltd., Mario Chiulli, Sleepy Hollow Motor Court, Inc., Riccardo Development Corp., Riccardo Realty Corp., and Mohawk Valley Land, Ltd., 887 F.2d 431, 2d Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Property List of Cases UpdatedDocument5 pagesProperty List of Cases UpdatedCamille BugtasNo ratings yet

- David J. Carlson Notice of AppealDocument5 pagesDavid J. Carlson Notice of AppealDavid J. CarlsonNo ratings yet

- 7 - Property PDFDocument2 pages7 - Property PDFAlyssa Lopez de LeonNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument1 pageSynopsisSamiul AlimNo ratings yet

- Mondragon V PeopleDocument3 pagesMondragon V PeoplequasideliksNo ratings yet

- JDF 78 Motion and Order To Set Aside Default JudgmentDocument2 pagesJDF 78 Motion and Order To Set Aside Default JudgmentSola Travesa100% (2)

- John Dekellis Robert Snell v. Microbilt Corporation, A Georgia Corporation First Financial Management Corporation, 131 F.3d 146, 1st Cir. (1997)Document3 pagesJohn Dekellis Robert Snell v. Microbilt Corporation, A Georgia Corporation First Financial Management Corporation, 131 F.3d 146, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lucia v. SECDocument4 pagesLucia v. SECBallotpediaNo ratings yet

- Gerald Kane v. Linda Cartisano, 3rd Cir. (2015)Document3 pagesGerald Kane v. Linda Cartisano, 3rd Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Roland Daniel Foster v. Ronald J. Champion, Warden Larry A. Fields, Director J.R. Pearman, Judge and The Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 107 F.3d 20, 10th Cir. (1997)Document3 pagesRoland Daniel Foster v. Ronald J. Champion, Warden Larry A. Fields, Director J.R. Pearman, Judge and The Attorney General of The State of Oklahoma, 107 F.3d 20, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Fam Law Case Comment SummaryDocument2 pagesFam Law Case Comment SummaryS VasanthNo ratings yet

- Thornton vs. Thornton: Jurisdiction over Child Custody Habeas Corpus PetitionsDocument1 pageThornton vs. Thornton: Jurisdiction over Child Custody Habeas Corpus PetitionsChanyeol ParkNo ratings yet

- Casiano V MalotoDocument1 pageCasiano V MalotonayowmeeNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dana B. Wilkerson, JR., A/K/A Tink Wilkerson, A/K/A D.B. Wilkerson, 951 F.2d 1261, 10th Cir. (1991)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Dana B. Wilkerson, JR., A/K/A Tink Wilkerson, A/K/A D.B. Wilkerson, 951 F.2d 1261, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Geonzon v. Heirs of LegaspiDocument1 pageGeonzon v. Heirs of LegaspiElaineMarcillaNo ratings yet

- 19 US v. Hernandez, 31 Phil. 343, August 26, 1915Document2 pages19 US v. Hernandez, 31 Phil. 343, August 26, 1915mae ann rodolfoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Lepowitch, 318 U.S. 702 (1943)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Lepowitch, 318 U.S. 702 (1943)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 186053 - DigestDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 186053 - DigestEdmund Pulvera Valenzuela II100% (1)

- Ujano vs. RepublicDocument5 pagesUjano vs. RepublicAira Mae LayloNo ratings yet