Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Von Stein 2019

Uploaded by

Meylindha Ekawati Biono PutriCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Von Stein 2019

Uploaded by

Meylindha Ekawati Biono PutriCopyright:

Available Formats

I nnovative Approaches

E FFECT OF A SCHEDULED

NURSE INTERVENTION ON

THIRST AND DRY MOUTH IN

INTENSIVE CARE PATIENTS

By Michelle VonStein, BSN, RN, CCRN, Barbara L. Buchko, DNP, RN, Cristina

Millen, BSN, RN, PCCN, Deborah Lampo, DNP, RN, NE-BC, Theodore Bell, MS,

and Anne B. Woods, PhD, MPH, RN

Background Thirst is a common, intense symptom

reported by hospitalized patients. No studies indicate

frequency of use of ice water and lip moisturizer with

menthol to ameliorate thirst and dry mouth. In an audit

of 30 intensive care unit patients at a 580-bed commu-

nity teaching hospital, 66% reported dry mouth with

higher thirst distress and intensity scores than in pub-

lished studies.

Objectives To evaluate the effectiveness of scheduled

use of ice water oral swabs and lip moisturizer with

menthol compared with unscheduled use in relieving

thirst and dry mouth for intensive care unit patients.

Methods In a quasi-experimental design, adult patients

admitted to 2 intensive care units at a community hos-

pital were provided with ice water oral swabs and lip

moisturizer with menthol upon request. The intervention

was unscheduled in 1 unit and scheduled in the other

unit. The scheduled intervention was provided hourly

during a 7-hour period (n = 62 participants). The unsched-

uled intervention consisted of usual care (n = 41 partici-

pants). A numeric rating scale (0-10) was used to measure

thirst intensity, thirst distress, and dry mouth before and

after 7 hours in both groups.

Results The scheduled-use group had significant lessen-

ing of thirst intensity (P = .02) and dry mouth (P = .008).

Thirst distress in the scheduled-use group did not differ

This article is followed by an AJCC Patient Care Page from that in the unscheduled-use group (P = .07).

on page 47. Conclusion Scheduled use of ice water oral swabs and

lip moisturizer with menthol may lessen thirst intensity

and dry mouth in critical care patients. (American Journal

©2019 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

of Critical Care. 2019;28:41-46)

doi:https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2019400

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, January 2019, Volume 28, No. 1 41

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 8, 2019

T

hirst can be defined as “a perception that provokes the urge to drink fluids”1 and “is

a prevalent, intense, distressing, and underappreciated symptom in intensive care

patients.”2 Dry mouth, or xerostomia, can be associated with thirst.1 Thirst and dry

mouth are common symptoms and may affect patients’ experience in intensive care

unit (ICUs).3 In a study of 171 ICU patients by Puntillo et al,4 thirst was one of the

most common and intense symptoms reported.

A more recent retrospective, descriptive study5 was tested in a randomized control study in 252 ICU

of patients who had cardiac surgery and received patients.1 Overall, use of the bundle resulted in a

mechanical ventilation confirmed that dry mouth statistically significant decrease in thirst intensity,

and thirst cause discomfort. The researchers5 sug- thirst distress, and dry mouth. These findings are

gested that these symptoms could be addressed by strengthened by the randomized control design of

nursing staff, but studies were needed to identify the study and assessment of potential confounders.

interventions. In a phenomenological study, Kjeld- In a quality improvement audit, we assessed for

sen et al6 found that patients treated with mechani- thirst distress, thirst intensity, and dry mouth in 30

cal ventilation experienced powerlessness and patients who were not receiving mechanical ventila-

frustration because of the inability to satisfy thirst. tion and whose status was nothing by mouth. Mean

Patients in ICUs are predisposed to thirst and scores for thirst distress and thirst intensity were 5.5

dry mouth for a variety of reasons, including mechan- and 6.1 (on a numeric rating scale [NRS] of 1-10),

ical ventilation, receiving nothing by mouth, specific respectively. Dry mouth was reported by 66% of

classes of medication, and certain medical conditions.7 patients. Usual care consisting of oral swabs moist-

Little research has been done ened with ice water and lip moisturizer containing

on nonpharmacological methyl lactate (a derivative of menthol) are provided

Patients receiving interventions to manage to patients upon request at this facility. More than

mechanical ventilation and minimize thirst and half of the patients reported using these interven-

dry mouth in hospitalized tions to relieve thirst and dry mouth.

experience powerless- adults, especially ICU Our aim in this study was to compare the effec-

patients, resulting in a lack tiveness of scheduled use of ice water oral swabs and

ness and frustration of solid evidence for prac- lip moisturizer with menthol with the effectiveness

because of the inability tice. Cold water was the of unscheduled, as-needed use of the same interven-

most common approach, tions (usual care) at relieving thirst intensity, thirst

to satisfy thirst. with a variety of application distress, and dry mouth in ICU patients. We hypoth-

techniques.1,3,8,9 Menthol esized that providing patients with regularly scheduled

was also cited as an intervention for its cooling sen- applications of ice water oral swabs and lip moistur-

sation.10 Puntillo et al1 used a menthol lip moistur- izer with menthol would decrease the patients’ per-

izer as part of an intervention bundle to prevent thirst ception of thirst intensity, thirst distress, and dry

and dry mouth. No evidence-based recommendations mouth more than would providing these interven-

for a standardized frequency of use were reported. tions upon patients’ request.

A thirst intervention bundle consisting of ice water

spray, oral swab wipes, and menthol lip moisturizer Methods

Design, Setting, and Sample

About the Authors We used a quasi-experimental study design with

Michelle VonStein and Cristina Millen are clinical nurses, a convenience sample of patients admitted to 2 medi-

and Deborah Lampo is a nurse manager, WellSpan York cal ICUs at WellSpan York Hospital, York, Pennsyl-

Hospital, York, Pennsylvania. Barbara L. Buchko is direc-

tor, Evidence-Based Practice and Nursing Research, and vania, a 580-bed acute care community teaching

Theodore Bell is a research program manager, WellSpan hospital. One unit provided the scheduled-use inter-

Health, York, Pennsylvania. Anne B. Woods is adjunct vention and the other unit provided usual care to

faculty, Messiah College, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania.

patients as needed. Both units provide care for ICU

Corresponding author: Barbara Buchko, Director of patients with a variety of medical diagnoses. The

Evidence-Based Practice and Nursing Research, Well-

Span Health, 1001 S George St, York, PA 17405 (email: study was approved by the appropriate institutional

bbuchko@wellspan.org). review board.

42 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, January 2019, Volume 28, No. 1 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 8, 2019

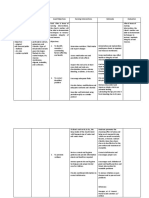

Assessed for eligibility

(n = 296) Excluded (n = 162)

Enrollment

Patients were eligible if they were more than 18 Not meeting inclusion

years old, spoke English, were able to provide informed criteria (n = 77)

consent, had an ICU stay of 12 hours or more, had Nonrandom assignment Declined participation

a score of -1, 0, or +1 on the Richmond Agitation- by unit (n = 85)

Sedation Scale, and had a baseline thirst intensity or (n = 134)

thirst distress score of 3 or greater (on a 0-10 NRS).

Allocation

The exclusion criteria mirrored those of the study of

Puntillo et al1: a history of dementia; open lesions Intervention unit Usual care unit

or desquamation on the mouth or lips; or a medical (n = 79) (n = 55)

condition, such as recent oral surgery, that contrain-

dicated the intervention. We did an a priori power

Follow-up

analysis for a paired t test with an _ of .05, a power Lost to follow-up Lost to follow-up

of 0.80, and an effect size of 0.35 (small-moderate). (n = 17) (n = 14)

The results indicated that 66 patients would be needed

for each group.

Analysis

A total of 296 patients were evaluated for eligi- Analyzed (n = 62) Analyzed (n = 41)

bility from February through September 2017. Of

these patients, 219 met eligibility criteria, and 134

(61%) were enrolled in the study. The Figure is a

Figure Flowchart of participants enrolled in the study.

flowchart of enrollment in the study. A total of 31

participants were lost to follow-up because of trans-

fer from the unit before completion of data collec- menthol. A reminder card was placed at each par-

tion. The 2 groups did not differ significantly (r21 = 0.3; ticipant’s bedside to ensure completion of sched-

P = .59) in the number who were lost to attrition: uled treatments. Clinical staff in the intervention

22% in the intervention group (n = 17) and 26% in unit were provided education about the interven-

the control group (n = 14). The final sample consisted tion and its frequency for participants.

of 103 patients who completed the study: 62 in the Control (Usual Care). Providing ice water oral

intervention group and 41 in the control group. swabs and lip moisturizer with menthol when

Participants who completed the study (n = 103) requested by a patient was the usual care. Study

and those who were lost because of attrition (n = 31) participants within the ICU that provided usual

did not differ significantly in age; sex; ventilator sta- care were notified that they could ask the clinical

tus; or scores for thirst intensity, thirst distress, and staff for ice water oral swabs

dry mouth obtained before the start of the study. and lip moisturizer with men-

thol when needed. The charge

The intervention

Procedures nurse and each participant’s group received hourly

Five research nurses were trained to enroll patients primary nurse in the usual-care

and collect data. These nurses used a researcher- ICU were notified that the par- ice water oral swabs

developed data collection tool to ensure precision ticipant was enrolled in a study. and lip moisturizer

in collection. Potential participants were identified No additional education was

each morning by a research nurse in collaboration provided to the nursing staff with menthol.

with the unit charge nurse. Baseline data were col- because no change in usual care

lected to determine eligibility. Patients who agreed was required. A research nurse returned to the

to participate completed an informed consent form. usual-care unit to evaluate the study participants’

Intervention. The research nurses informed par- thirst intensity, thirst distress, and dry mouth 7 hours

ticipants in the intervention group that clinical staff after enrollment (between 5:30 PM and 6 PM)

members would provide freshly obtained ice water

oral swabs and would apply lip moisturizer with Instruments

menthol every hour with the first application at 10 AM Construct validity of the NRS was established

and the last application at 5 PM. The research nurses through factor analysis.11,12 Concurrent validity was

informed the unit charge nurse and each patient’s evidenced by strong correlations between scores on

primary nurse of the patient’s enrollment in the study. the NRS and scores on a visual analog scale, current

Participants in the intervention group received a pain intensity word scales, and simple descriptive

packet containing 8 swabs and lip moisturizer with scales.11,12 We chose an NRS rather than a visual

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, January 2019, Volume 28, No. 1 43

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 8, 2019

Table 1

Group demographics

Intervention Control groupa

Data Analysis

Characteristic groupa (n = 62) (n = 41) P value

We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version

Male sex 33 (53) 24 (59) .60 24.0, (IBM Corp) to maintain and analyze data. To

Ventilator status 1 (2) 1 (2) > .99 evaluate differences between the scheduled-use group

10 (16) 6 (15) > .99

and the control group for demographics (sex, venti-

Nothing by mouth status

lator status, and nothing by mouth status), we used

Age, mean (SD), y 60.3 (17.1) 62.8 (11.3) .41

the Pearson r2 test or the Fisher exact test as appropri-

a

Values are No. (%) of patients unless otherwise indicated in first column.

ate. Differences in age between the 2 groups were eval-

uated by using an independent samples t test. The

outcome variables (number of ice water swabs used

Table 2 and number of times lip moisturizer with menthol

Paired samples results for intervention was used), along with scores for thirst intensity, thirst

and control groupsa distress, and dry mouth, were examined to assess

Score, mean (SD)

assumptions for parametric testing. These data violated

Group Outcomes Before After Z P valueb

the assumptions of normality (kurtosis ≥ 1.0; Shapiro

Wilk test < .05), so nonparametric analyses were used.

Intervention Thirst intensity 6.48 (2.45) 3.65 (2.84) -5.10 < .001 The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to identify dif-

Thirst distress 5.21 (2.95) 2.73 (3.03) -4.57 < .001

ferences in scores before and after the intervention in

Dry mouth 6.63 (2.57) 3.48 (2.84) -5.36 < .001

both the intervention and the control groups. The

Control Thirst intensity 7.10 (2.41) 5.42 (2.87) -3.29 .001 Mann-Whitney test was used to detect significant dif-

Thirst distress 5.83 (3.20) 4.18 (3.40) -2.57 .01

Dry mouth 6.76 (2.95) 5.20 (2.97) -2.66 .008

ferences in the mean use of ice water oral swabs and

lip moisturizer with menthol between the intervention

a

Scores were on a numeric rating scale. and control groups and to detect differences in mean

b

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

difference scores before and after the intervention in

the intervention and control groups for thirst intensity,

Table 3 thirst distress, and dry mouth. Statistical significance

Comparison of mean difference scores for was established as P less than .05.

thirst intensity, thirst distress, and dry moutha

Score Mean Results

Outcomes Group Before After difference P value Sample Characteristics

A total of 103 patients completed the study, 62

Thirst intensity Intervention 6.48 3.65 -2.84 .02

Control 7.10 5.42 -1.68

in the scheduled-use group and 41 in the control

group. The 2 groups did not differ significantly in

Thirst distress Intervention 5.21 2.73 -2.48 .07

sex (P = .60), ventilator status (P > .99), nothing by

Control 5.83 4.18 -1.65

mouth status (P > .99) or age (P = .41; see Table 1).

Dry mouth Intervention 6.63 3.48 -3.15 .008

Control 6.76 5.20 -1.56

Findings

a

Mann-Whitney test. In the total sample, thirst intensity, thirst dis-

tress, and dry mouth were reported as substantial

analog scale (as used by Puntillo et al1) because symptoms, with mean NRS scores of 6.73 (SD, 2.4),

patients are familiar with the 0 to 10 NRS. Measures 5.46 (SD, 3.1), and 6.68 (SD, 2.7), respectively. Mean

for thirst intensity and thirst distress mirrored those use of ice water oral swabs and lip moisturizer with

used by Puntillo et al.1 Thirst intensity was scored menthol was significantly greater in the intervention

as 0 (no thirst) to 10 (worst possible thirst); thirst group than in the control group: oral swabs, 5.4 vs

distress as 0 (no distress) to 10 (worst possible dis- 1.7 (P < .001); lip moisturizer with menthol, 4.4 vs

tress); and dry mouth as 0 (no dryness) to 10 (worst 0.5 (P < .001). The 2 groups did not differ significantly

possible dryness). Participants who were unable to in the mean preintervention scores obtained within

communicate verbally because of endotracheal intu- 1 hour of the time the study began for thirst inten-

bation were shown a paper copy of the NRS and asked sity (P = .22), thirst distress (P = .22), or dry mouth

to point to the number that corresponded to their (P = .68). Although both the intervention and the

thirst intensity, thirst distress, and dry mouth or to control group had significant decreases in all 3 out-

nod affirmatively when the research nurse pointed comes (Table 2), the magnitude of the differences

to the numbers, as done in an earlier study.1 was greatest in the intervention group (Table 3), with

44 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, January 2019, Volume 28, No. 1 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 8, 2019

significant statistical differences for thirst intensity in clarifying thirst distress to participants, a situation

(-2.84 vs -1.68, U = 941.5, Z = -2.24, P = .02) and dry that may have affected the participants’ rating of

mouth (-3.15 vs -1.56, U = 877.5, Z = -2.66, P = .008). thirst distress. In addition, possible underlying dif-

These findings were also clinically significant, with ferences between the 2 units could have inadvertently

medium-effect sizes for thirst intensity (Cohen d = 0.4) confounded the findings. Randomization to groups

and dry mouth (Cohen d = 0.5). was not done; clear separa-

Discussion

tion of the intervention group

and the control group ensured

Thirst intensity, thirst

Thirst and dry mouth are substantial symptoms intervention fidelity. Also, distress, and dry mouth

experienced by patients in ICUs. Our preinterven- some study participants might

tion mean scores for thirst intensity, thirst distress, have received cold water swabs

were reported as

and dry mouth are similar to those reported by Wang rather than ice water swabs; substantial symptoms.

et al,5 who used a visual analog scale to measure we did not require measure-

thirst and dry mouth associated with discomfort in ment of water temperature to confirm use of ice

patients receiving mechanical ventilation. The mean water. Our study was limited to 2 ICUs in a single

value for thirst and dry mouth in their multiple hospital; therefore, our findings cannot be general-

regression analysis was 5.789 (P = .04), indicating ized to other types of acute inpatient units. Our

that these 2 symptoms were significant predictors of study sample had few patients receiving mechanical

discomfort in patients treated with mechanical ven- ventilation. Puntillo et al1 also had few patients

tilation. Wang et al5 recognized thirst and dry receiving mechanical ventilation and suggested

mouth as a problem and recommended further that interventions for thirst intensity, thirst distress,

research for interventions. and dry mouth may be beneficial to these patients.

Puntillo et al1 investigated interventions. Of note, Therefore, additional research is needed to generalize

Puntillo et al1 measured thirst intensity and thirst our interventions for other populations of patients.

distress by using a 0 to 10 NRS as we did but measured

dry mouth by using a dichotomous (yes-no) mea- Conclusions

sure, whereas we used an NRS. Our preintervention Thirst and dry mouth are the result of illness,

findings for thirst intensity and thirst distress scores medications, and other interventions that patients

were higher than those of Puntillo et al1; however, receive in ICUs. These symptoms are uncomfortable

both their study and ours indicated improvement and distressing, but they are not routinely assessed

in each group. Puntillo et al1 found significant or treated. Thirst must compete with a cadre of other

improvement with use of interventions in thirst symptoms that have greater potential to adversely

intensity, thirst distress, and dry mouth, whereas affect patient outcomes. Our findings confirm that

we found significant improvement in thirst inten- thirst intensity, thirst distress, and dry mouth are

sity and dry mouth only. This difference may be common distressing symptoms among patients in

due to participants’ difficulty in understanding the ICUs. Nurses play a pivotal role in the assessment

concept of thirst distress. Data collectors in our and identification of these symptoms. Compared

study reported the need to explain and use various with as-needed interventions, implementation of a

terms for clarification. simple, scheduled protocol

A strength of our study is that the clinical staff to reduce these symptoms

who provided the intervention could readily incor- can increase patient com-

Implementing a simple

porate these practices with hourly rounding, a situa- fort. Scheduled, hourly scheduled protocol to

tion that supports the feasibility of implementing applications of ice cold

these interventions in the clinical setting. Our study water oral swabs and lip reduce symptoms of

has limitations. Because of challenges with staffing

and patient enrollment, the sample did not meet

moisturizer with menthol

are simple interventions

thirst and dry mouth can

the recommended size of 66 for each group as that can easily be incorpo- increase patient comfort.

determined by the a priori power analysis. Although rated with other hourly

power was sufficient to detect a significant difference rounding interventions. These interventions can be

for thirst intensity and dry mouth in both the inter- used to engage patients and patients’ families to

vention and control groups, the lack of statistical participate more actively in the plan of care. Further

significance for thirst distress may be due to a type research with larger sample sizes is needed to gener-

II error related to insufficient power. Variations occurred alize our findings to other populations of patients.

www.ajcconline.org AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, January 2019, Volume 28, No. 1 45

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 8, 2019

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 6. Kjeldsen C, Hansen M, Jensen K, Holm A, Haahr A, Dreyer

This research was performed at WellSpan York Hospital. P. Patients’ experience of thirst while being conscious and

mechanically ventilated in the intensive care unit. Nurs Crit

Care. 2018;23(2):75-81.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

7. Arai S, Stotts N, Puntillo K. Thirst in critically ill patients:

Funding for this study was provided through a grant from from physiology to sensation. Am J Crit Care. 2013;22(4):

the George L. Laverty Foundation. 328-335.

8. Brunstrom J. Effects of mouth dryness on drinking behav-

REFERENCES ior and beverage acceptability. Physiol Behav. 2002;76(3):

1. Puntillo K, Arai S, Cooper B, Stotts N, Nelson J. A randomized 423-429.

clinical trial of an intervention to relieve thirst and dry 9. Brunstrom J, Macrae A. Effects of temperature and volume

mouth in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med. on measures of mouth dryness, thirst, and stomach full-

2014;40(9):1295-1302. ness in males and females. Appetite. 1997;29(1):31-42.

2. Stotts N, Arai S, Cooper B, Nelson J, Puntillo K. Predictors 10. Eccles R. Role of cold receptors and menthol in thirst, the

of thirst in intensive care unit patients. J Pain Symptom drive to breathe and arousal. Appetite. 2000;34(1):29-35.

Manage. 2015;49(3):530-508. 11. Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA,

3. Puntillo K, Nelson J, Weissman D, et al; Advisory Board of Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum

the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU (IPAL-ICU) Project. Dis. 1978;37(4):378-381.

Palliative care in the ICU: relief of pain, dyspnea, and thirst— 12. Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical

a report from the IPAL-ICU Advisory Board. Intensive Care pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain. 1986;

Med. 2014;40(2):235-248. 27(1):117-126.

4. Puntillo LA, Arai S, Cohen NH, et al. Symptoms experi-

enced by intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying.

Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2155-2160.

5. Wang Y, Li H, Zou H, Li Y. Analysis of complaints from To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact American

patients during mechanical ventilation after cardiac sur- Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 101 Columbia, Aliso

gery: a retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. Viejo, CA 92656. Phone, (800) 899-1712 or (949) 362-2050

2015;29(4):990-994. (ext 532); fax, (949) 362-2049; email, reprints@aacn.org.

46 AJCC AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE, January 2019, Volume 28, No. 1 www.ajcconline.org

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 8, 2019

Effect of a Scheduled Nurse Intervention on Thirst and Dry Mouth in Intensive Care

Patients

Michelle VonStein, Barbara L. Buchko, Cristina Millen, Deborah Lampo, Theodore Bell and Anne B.

Woods

Am J Crit Care 2019;28 41-46 10.4037/ajcc2019400

©2019 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

Published online http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/

Personal use only. For copyright permission information:

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/cgi/external_ref?link_type=PERMISSIONDIRECT

Subscription Information

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/

Information for authors

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/misc/ifora.xhtml

Submit a manuscript

http://www.editorialmanager.com/ajcc

Email alerts

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/subscriptions/etoc.xhtml

The American Journal of Critical Care is an official peer-reviewed journal of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

(AACN) published bimonthly by AACN, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Telephone: (800) 899-1712, (949) 362-2050, ext.

532. Fax: (949) 362-2049. Copyright ©2016 by AACN. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/ by AACN on January 8, 2019

You might also like

- Textbook of Oral Medicine Oral Diagnosis and Oral RadiologyDocument924 pagesTextbook of Oral Medicine Oral Diagnosis and Oral RadiologyAnonymous Bt6favSF4Y90% (67)

- NCP Impaired Oral Mucous MembraneDocument2 pagesNCP Impaired Oral Mucous Membraneklemtot83% (6)

- Oral Manifestation of Systemic DiseaseDocument137 pagesOral Manifestation of Systemic DiseaseJeff Burgess100% (3)

- MFDS Questions ImpDocument8 pagesMFDS Questions ImpalkaNo ratings yet

- HH 2Document6 pagesHH 2LestiNo ratings yet

- Management of Dry Mouth Symptoms After Polysaccharide RinseDocument8 pagesManagement of Dry Mouth Symptoms After Polysaccharide Rinseotoralla1591No ratings yet

- MagicMouthwash For OralMucositis Sol Stanford PDFDocument2 pagesMagicMouthwash For OralMucositis Sol Stanford PDFManuel ArenasNo ratings yet

- Oral Care Reduces Pneumonia in Older Patients in Nursing HomesDocument4 pagesOral Care Reduces Pneumonia in Older Patients in Nursing HomesYasir MahfudNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Dental Research, Dental Clinics, Dental ProspectsDocument8 pagesOriginal Article: Dental Research, Dental Clinics, Dental Prospectsmadhu kakanurNo ratings yet

- Weissman 2011Document5 pagesWeissman 2011gulararezendeNo ratings yet

- Comparing Nasal Irrigation Devices for Pediatric SinusitisDocument6 pagesComparing Nasal Irrigation Devices for Pediatric SinusitisrivanaNo ratings yet

- PneumoniaDocument8 pagesPneumoniaSoffie FitriyahNo ratings yet

- Doxycycline: An Option in The Treatment of Ulcerated Oral Lesions?Document6 pagesDoxycycline: An Option in The Treatment of Ulcerated Oral Lesions?nnNo ratings yet

- Chitsuthipakorn 2021Document12 pagesChitsuthipakorn 2021Diko KoestantyoNo ratings yet

- Oxitard Capsules Improve Oral Submucous Fibrosis SymptomsDocument5 pagesOxitard Capsules Improve Oral Submucous Fibrosis SymptomssevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- Management of Endodontic Emergencies: Chapter OutlineDocument9 pagesManagement of Endodontic Emergencies: Chapter OutlineNur IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Kjped 57 479Document5 pagesKjped 57 479Vincent LivandyNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S009923991500182X MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S009923991500182X MainDaniella NúñezNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Standard Versus Comprehensive Oral Care Protocol Among Intubated Neuroscience ICU Patients: Results of A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument13 pagesEffects of A Standard Versus Comprehensive Oral Care Protocol Among Intubated Neuroscience ICU Patients: Results of A Randomized Controlled TrialMohammed Falih HassanNo ratings yet

- Oral Care May Reduce Pneumonia Risk in Tube-Fed ElderlyDocument6 pagesOral Care May Reduce Pneumonia Risk in Tube-Fed ElderlyIvan Ramos GutarraNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Efficacy of Buccal Infiltration Articaine Versus Lidocaine For Extraction of Primary Molar TeethDocument5 pagesAnesthetic Efficacy of Buccal Infiltration Articaine Versus Lidocaine For Extraction of Primary Molar TeethFabro BianNo ratings yet

- 2887 10028 1 PBDocument5 pages2887 10028 1 PBniratig691No ratings yet

- Clinically Proven Herbal Toothpaste in Sri LankaDocument7 pagesClinically Proven Herbal Toothpaste in Sri LankaYoga ChanNo ratings yet

- Tes MenelanDocument9 pagesTes MenelanAnonymous q1NLY8RNo ratings yet

- FinalprintedarticleDocument9 pagesFinalprintedarticleNia DefinisiNo ratings yet

- Xylitol Nasal Irrigation in The Management of ChronicDocument6 pagesXylitol Nasal Irrigation in The Management of ChronicFlor OMNo ratings yet

- One Stage Full-Mouth Disinfection Improves Periodontitis OutcomesDocument14 pagesOne Stage Full-Mouth Disinfection Improves Periodontitis OutcomesAnita PrastiwiNo ratings yet

- Irrigacion Iodo Vs Agua OxigenadaDocument5 pagesIrrigacion Iodo Vs Agua OxigenadaAlanis BuenrostroNo ratings yet

- Effects of Parentereal Hydration in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients A Preleminary StudyDocument6 pagesEffects of Parentereal Hydration in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients A Preleminary StudyCristian Meza ValladaresNo ratings yet

- A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial of Normal Saline, Lactated Ringer's, and Hypertonic Saline Nasal Irrigation Solution After Endoscopic Sinus SurgeryDocument7 pagesA Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial of Normal Saline, Lactated Ringer's, and Hypertonic Saline Nasal Irrigation Solution After Endoscopic Sinus SurgeryYasdika ImamNo ratings yet

- Sample of Journal & Critique PresenationDocument42 pagesSample of Journal & Critique PresenationMonika shankarNo ratings yet

- Joph2019 5491626Document5 pagesJoph2019 5491626rizki agusmaiNo ratings yet

- tratamiento con AINESDocument6 pagestratamiento con AINESCarol Chávez MedinaNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Onset Time and Injection Pain Between Buffered and Unbuffered Lidocaine Used As Local Anesthetic For Dental Care in ChildrenDocument4 pagesAnesthesia Onset Time and Injection Pain Between Buffered and Unbuffered Lidocaine Used As Local Anesthetic For Dental Care in ChildrenFernando MenesesNo ratings yet

- Clinical Efficacy of Local Delivered Minocycline in The Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis Smoker PatientsDocument5 pagesClinical Efficacy of Local Delivered Minocycline in The Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis Smoker PatientsvivigaitanNo ratings yet

- Tap Water Versus Sterile Normal Saline in Wound Swabbing: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled TrialDocument8 pagesTap Water Versus Sterile Normal Saline in Wound Swabbing: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled TrialAnonymous RxjOeoYn9No ratings yet

- Univer Complu Madrid NBF Peri - Implant MucositisDocument10 pagesUniver Complu Madrid NBF Peri - Implant Mucositisjuan perezNo ratings yet

- Referensi 5Document5 pagesReferensi 5RizkaGayoNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Povidone Iodine (PH 4.2) On Patients With Adenoviral ConjunctivitisDocument3 pagesThe Effects of Povidone Iodine (PH 4.2) On Patients With Adenoviral ConjunctivitisShari' Si WahyuNo ratings yet

- Hamre - 2012 - Pulpa Dentis D30 For Acute Reversible Pulpitis A Prospective Cohort Study in Routine Dental PracticeDocument7 pagesHamre - 2012 - Pulpa Dentis D30 For Acute Reversible Pulpitis A Prospective Cohort Study in Routine Dental PracticeMaría Reynel TarazonaNo ratings yet

- Determination of Salivary Levels of Mucin and Amylase in Chronic Periodontitis PacientsDocument7 pagesDetermination of Salivary Levels of Mucin and Amylase in Chronic Periodontitis PacientsOctavian BoaruNo ratings yet

- Avaliacao Quantitativa FuncaooralDocument6 pagesAvaliacao Quantitativa FuncaooralAMELIA PAZ LETELIER AGUIRRENo ratings yet

- Topical Application of Local Anaesthetic Gel VS IcDocument7 pagesTopical Application of Local Anaesthetic Gel VS IcNhấtNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of buffered and non-buffered local anaesthetic in inferior alveolar nerve block: a randomised studyDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of buffered and non-buffered local anaesthetic in inferior alveolar nerve block: a randomised studykaluaxeniaNo ratings yet

- Oral Care in Ventilation MechanicDocument8 pagesOral Care in Ventilation MechanicRusida LiyaniNo ratings yet

- Çocuklarda Sıvı Tedavisi Ile Pobk Arasındaki IlişkiDocument6 pagesÇocuklarda Sıvı Tedavisi Ile Pobk Arasındaki IlişkiAli ÖzdemirNo ratings yet

- Daily Interruption of Sedation in Patients Receiving Mechanical VentilationDocument10 pagesDaily Interruption of Sedation in Patients Receiving Mechanical VentilationJim LinNo ratings yet

- Management of Dentinehypersensitivity Ef Cacy Ofprofessionally Andself-Administered AgentsDocument47 pagesManagement of Dentinehypersensitivity Ef Cacy Ofprofessionally Andself-Administered AgentsNaoki MezarinaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan for Oral Mucosa InjuryDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan for Oral Mucosa InjurySweetie PieNo ratings yet

- Could Patient Controlled Thirst Driven Fluid Administration 2018 British JouDocument7 pagesCould Patient Controlled Thirst Driven Fluid Administration 2018 British JouSeveNNo ratings yet

- Uri 2011Document5 pagesUri 2011anton.neonatusNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Efficacy of Dentin Hypersensitivity Treatments-A Systematic Review and Follow Up AnalysisDocument39 pagesEvaluation of The Efficacy of Dentin Hypersensitivity Treatments-A Systematic Review and Follow Up AnalysisNaoki MezarinaNo ratings yet

- Evidencia 2Document3 pagesEvidencia 2Alex MolinaNo ratings yet

- Hyaluronic Acid As An Adjunct After Scaling and Root Planing A Prospective Randomized Clinical TrialDocument9 pagesHyaluronic Acid As An Adjunct After Scaling and Root Planing A Prospective Randomized Clinical TrialAdriana Segura DomínguezNo ratings yet

- Journal of Population Therapeutics & Clinical PharmacologyDocument7 pagesJournal of Population Therapeutics & Clinical PharmacologyEka SetyariniNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of Effectiveness Between Topical Insulin Versus Normal Saline Dressings in Management of Diabetic Foot UlcersDocument13 pagesA Comparative Study of Effectiveness Between Topical Insulin Versus Normal Saline Dressings in Management of Diabetic Foot UlcersIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of 25% Glucose in Glycerin and Honey in The Management of Primary Atrophic Rhinitis: A Comparative Prospective StudyDocument4 pagesEfficacy of 25% Glucose in Glycerin and Honey in The Management of Primary Atrophic Rhinitis: A Comparative Prospective StudySathiyamoorthy KarunakaranNo ratings yet

- Parirokh 2016Document7 pagesParirokh 2016Fernando MenesesNo ratings yet

- Role of PH of External Auditory Canal in Acute Otitis ExternaDocument6 pagesRole of PH of External Auditory Canal in Acute Otitis ExternaAayush MittalNo ratings yet

- Efficacy-of-a-Moisturizer-for-Pruritus-AccompaniedDocument9 pagesEfficacy-of-a-Moisturizer-for-Pruritus-Accompaniedachi olivNo ratings yet

- General Anaesthesia in The Dental Management of A Child With Cerebral Palsy and Autism: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesGeneral Anaesthesia in The Dental Management of A Child With Cerebral Palsy and Autism: A Case Reportulum777No ratings yet

- Pone 0145837Document16 pagesPone 0145837Raluca ChisciucNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughFrom EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughSang Heon ChoNo ratings yet

- Reliabilityand Validityof Research InstrumentsDocument9 pagesReliabilityand Validityof Research InstrumentsMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Analisis Ulangan Umum Semester II Tahun 2014 - 2015Document36 pagesAnalisis Ulangan Umum Semester II Tahun 2014 - 2015Meylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Kawati Biono Putri., S.KepDocument1 pageKawati Biono Putri., S.KepMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Reliabilityand Validityof Research InstrumentsDocument9 pagesReliabilityand Validityof Research InstrumentsMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Slow Deep Breathing and Lavender Aromatherapy for Post-Caesarean Section PainDocument8 pagesSlow Deep Breathing and Lavender Aromatherapy for Post-Caesarean Section PaineviNo ratings yet

- Contoh CV ProfesionalDocument2 pagesContoh CV ProfesionalElyani AdityaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Scores For Dyspnoea Severity in Children: A Prospective Validation StudyDocument11 pagesClinical Scores For Dyspnoea Severity in Children: A Prospective Validation StudyMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: PICU Nurses' Pain Assessments and Intervention Choices For Virtual Human and Written VignettesDocument21 pagesHHS Public Access: PICU Nurses' Pain Assessments and Intervention Choices For Virtual Human and Written VignettesMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Position On Gastric Residual Volume of Premature Infants in NICUDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Position On Gastric Residual Volume of Premature Infants in NICUMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Published Sandeep STM JNSPDocument5 pagesPublished Sandeep STM JNSPMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Contoh CV ProfesionalDocument1 pageContoh CV ProfesionalMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka: 9454332/penderita - Stroke.di - Yogyakarta.Meningkat. Dua - Kali.LipatDocument4 pagesDaftar Pustaka: 9454332/penderita - Stroke.di - Yogyakarta.Meningkat. Dua - Kali.LipatMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Gynecologic Oncology: Nozomi Donoyama, Toyomi Satoh, Tetsutaro Hamano, Norio Ohkoshi, Mamiko OnukiDocument8 pagesGynecologic Oncology: Nozomi Donoyama, Toyomi Satoh, Tetsutaro Hamano, Norio Ohkoshi, Mamiko OnukiMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Archives of Psychiatric Nursing: Funda Kavak, Mine EkinciDocument7 pagesArchives of Psychiatric Nursing: Funda Kavak, Mine EkinciMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- 197 377 1 SMDocument29 pages197 377 1 SMMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- WhoDocument1 pageWhoMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- 2015-03-28 - 10-04-09-Ambm 17Document5 pages2015-03-28 - 10-04-09-Ambm 17Meylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- 46 HalpinDocument3 pages46 HalpinMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument7 pages1 PBDelly AwalliaNo ratings yet

- Food ChemistryDocument6 pagesFood ChemistryMeylindha Ekawati Biono PutriNo ratings yet

- Assets Documents Reports Clinical Guidelines in Dentistry For Diabetes 2015Document62 pagesAssets Documents Reports Clinical Guidelines in Dentistry For Diabetes 2015PragatiNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Prosthodontic Management of Xerostomic Patient: A Technical ModificationDocument7 pagesCase Report: Prosthodontic Management of Xerostomic Patient: A Technical ModificationLisa Purnia CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Oral Healthcare For The Elderly in Malaysia PDFDocument58 pagesOral Healthcare For The Elderly in Malaysia PDFEr LindaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care in RadiotherapyDocument26 pagesNursing Care in Radiotherapyحسام جبار مجيد100% (1)

- GIT Biochem PDFDocument46 pagesGIT Biochem PDFMohammad ShafiqNo ratings yet

- Oral Manifestations of Connective Tissue DiseasesDocument34 pagesOral Manifestations of Connective Tissue DiseasesFatin Nabihah Jamil67% (3)

- Contoh CJRDocument16 pagesContoh CJRmmerry743No ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus and Prosthodontic Care Chanchal Katariya & Dr. SangeethaDocument3 pagesDiabetes Mellitus and Prosthodontic Care Chanchal Katariya & Dr. SangeethaArushi AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Saliva's potential as a non-invasive diagnostic toolDocument9 pagesSaliva's potential as a non-invasive diagnostic toolSabiran GibranNo ratings yet

- Ecologia de Lactobacilus en La Cavidad BucalDocument11 pagesEcologia de Lactobacilus en La Cavidad BucalLucy Esther Calvo PerniaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Saliva For Therapeutic Management of Xerostomia: A Structured ReviewDocument5 pagesArtificial Saliva For Therapeutic Management of Xerostomia: A Structured ReviewAlexander KevinNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Salivary GlucoseDocument10 pagesEstimation of Salivary GlucoseSuganya MurugaiahNo ratings yet

- The Correlation Between Occurrence of Dental Caries and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life On Elderly Population in Yogyakarta Special RegionDocument10 pagesThe Correlation Between Occurrence of Dental Caries and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life On Elderly Population in Yogyakarta Special RegionClaypella MaskNo ratings yet

- What Is Dry MouthDocument1 pageWhat Is Dry Mouthالعمري العمريNo ratings yet

- Sjogren Syndrome: Schirmer TestDocument2 pagesSjogren Syndrome: Schirmer TestRiena Austine Leonor NarcillaNo ratings yet

- Oral and dental infections and disordersDocument59 pagesOral and dental infections and disordersHendra PranotogomoNo ratings yet

- BL NurBio Activity 11 - Analysis of Saliva (Revised 07.05.20)Document4 pagesBL NurBio Activity 11 - Analysis of Saliva (Revised 07.05.20)Diana CoralineNo ratings yet

- Sarmiento vs. ECC GR No. 65680, May 11, 1988Document3 pagesSarmiento vs. ECC GR No. 65680, May 11, 1988Winnie Ann Daquil LomosadNo ratings yet

- Pros Tho Don Tic Considerations in Diabetes MellitusDocument16 pagesPros Tho Don Tic Considerations in Diabetes MellitusDrPrachi AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Oral Dysfunction in Patients With Head and Neck.10Document14 pagesOral Dysfunction in Patients With Head and Neck.10Yeni PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Saliva: DR - Deepshikha Soni Mds 1 YearDocument90 pagesSaliva: DR - Deepshikha Soni Mds 1 Yeardisha 146jandialNo ratings yet

- Connective Tissue DisordersDocument35 pagesConnective Tissue DisordersAHMED KHALIDNo ratings yet

- Japanese Dental Science Review: Yumiko Kawashita, Sakiko Soutome, Masahiro Umeda, Toshiyuki SaitoDocument6 pagesJapanese Dental Science Review: Yumiko Kawashita, Sakiko Soutome, Masahiro Umeda, Toshiyuki SaitoYeni PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Throat PowerpointDocument29 pagesThroat Powerpointminci sensei100% (8)

- 2 Saliva PhysiologyDocument20 pages2 Saliva PhysiologyvelangniNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Sjögren's Syndrome - Constitutional and Non-Sicca Organ-Based Manifestations - UpToDateDocument31 pagesTreatment of Sjögren's Syndrome - Constitutional and Non-Sicca Organ-Based Manifestations - UpToDateGabriel Fernandez FigueroaNo ratings yet