Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AffectImpactonAdMemory PDF

Uploaded by

antra vOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AffectImpactonAdMemory PDF

Uploaded by

antra vCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/288284979

The impact of affect on memory of advertising

Article in Journal of Advertising Research · March 1999

CITATIONS READS

89 2,839

2 authors, including:

Tim Ambler

London Business School

105 PUBLICATIONS 6,121 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

None. Now retired but thanks for asking View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Tim Ambler on 24 March 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The Impact of Affect on Memory

of Advertising

The impact of affect on memory has been considered by both advertising and

neuroscience research. As part of testing a MAC (Memory zi Affect Z) Cognition) model

of the intermediate effects of advertising, four hypotheses were developed: ads with

higher affective content would have higher recognition and recall, and subjects treated

with p-blockers (Propranolol), which interact with those brain regions known to

mediate affect, would have lower recognition and recall than those treated with

placebos. The hypotheses are tested and broadly supported. This exploratory

research, taken in conjunction with previous work, indicates some ways in which

affect enhances advertising effectiveness. We conclude with directions for further

research and testing the MAC model.

TIM AMBLER WE KNOW THAT EFFECTIVE advertising must change ad memory (recall and recognition). After discus-

London Business long-term memory because of the interval be- sion of the results, implications, and limitations,

School tween ad exposure and its impact on behavior. we conclude with suggestions for further testing

\

How that memory change is achieved, and how to of the model.

measure it, are less understood. Advertisers have

long used recognition and recall measures though THEORY DEVELOPMENT

they have been challenged (Gibson, 1983; Lodish Before memory issues, we re\ ieu' the impact of the

et al., 1995; Percy and Rossiter, 1997). ad on how we think and feel. Much of the history

The mainstream of-advertising research rests on of advertising research has been preoccupied with

cognition as the primary factor of memory change. cognitive, as distinct from affective, brain pro-

Advertising has been thought to need a unique cesses. Advertising was seen as providing infor-

selling proposition, new news, a logical associa- mation and reasons to buy and/or prefer the

tion, or to remind consumers of memories already brand advertised. More recently, the sptitlight has

in place. The smaller and more recent stream fo- shifted to include affect as has neuroscience:

cuses on affect, such as liking the ad (Biel, 1990; "Neuroscientists have, in modem times, been es-

TOM BURNE

Haley and Baidinger, 1991; Joyce, 1991). pecially concerned with the neural basis of cttgni-

The Open University

This research used p-blockers experimentally to tive processes such as perception and memor\'.

test the impact of affect on the formation of ad They have for the most part ignored the brain's

memories, as measured by recall and recognition. role in emotion" (LeDoux, 1994).

The authors Ibaiik especial!^

The ingestion of |3-blockers inhibits the experience Damasio (1994) distinguishes emotions (body

Professor Stiivii Rofc mni Dr.

of emotion though they do not remove the sub- state) from feelings (mental state), whereas Cham-

Sliiart Fifhcr nf Opai Unitvr-

ject's ability to recognize emotion in the stimulus bers Dictionary (1993) defines affect as "the emo-

si/y and fliejbur anoniiinous

(Greenblatt et al., 1993; CahiU et al., 1994). They tion that lies behind action" with the implication

sponsors of this research. Also

have no impact on attention nor cognitive that emotion is a mental state. To a\ oid these dis-

thanks go to Profrssors Patrick

faculties. tinctions, this paper uses emotion, affect, and feel-

Barn'isc, Knit Craysou, ISrucc

Hatdie, CilMcWitliam. HK edi-

This paper reports on a small experiment set in ing interchangeably but in contrast with cogniticm

tor, mid rei'ieiceri for comments

a wider theoretical context of how advertising (knowledge and thinking).

I'll drafts and encouraging ihe

works. A model of the cognitive, affective, and The advertising literature, has been dominated

project. memory effects of advertising is drawn from the by "persuasive hierarchy" or "hierarchy of effects"

neuroscience and marketing literature. As a partial models (Hoibrook, 1986; for reviews, see

E-mail: TAmbkr®lbs.ac.uk probe of this model, we empirically test four hy- O'Shaughnessy, 1992; Vakratsas and Ambler,

tom.bu Tne®bbfrc.ac. uk potheses dealing with the interaction of affect with 1999). In these, advertising is mentally processed

March . April 1 9 9 9 JDIIRnriL OF HDUERTISlOe RESERRCH 2 5

AD MEMORY

sequentially in a series of stages, typically ings and social skills—affect, not cogni- versity of California, Irvine. P-blockers,

C 0 A 1) B (cognition 0 affect 0 behavior). tion. Patients with lesions in the ventro- conventionally used as antidepressants or

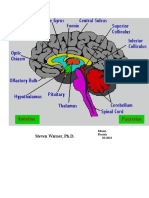

Each is a gate, e.g., an ad rejected by ra- medial frontal lobes (VMFL—see Figure stress relievers, reduce affective responses

tional analysis will not reach the next 1) did not experience the appropriate feel- to stimuli (Greenblatt et al., 1993) and also

stage. ings to the stimuli. As a result of prior selectively impaired long-term (one week)

In contrast, some theories purely focus conditioning they knew what feelings memory for emotionally arousing short

on the affective responses, familiarity, and they should have had but were not moved stories (Cahill et al., 1994). CahiU et al.

feelings that the ads evoke (see, for ex- in those ways. His findings are supported (1995) reported a patient (B. P.), with nor-

ample, Alwitt and Leavitt, 1985; Aaker, by Adolphs et al. (1994) and Phelps and mal cognitive functions but damage to the

Stayman, and Hagerty, 1986; Peterson, Anderson (1997). amygdaloid complex', who did not have

Hoyer, and Wilson, 1986), Consumers Memory makes the connection between the enhanced memory for the emotional

form their preferences based on feelings, advertising inputs and behavior: there part of the story that normal controls had.

such as liking, induced by the ad or famil- seems reason to believe that affect, rather Memory for the nonemotional part of the

iarity triggered by mere exposure to the than cognition, may be the key. Brain lo- story was normal. McGaugh, Cahili, and

ad, rather than product/brand attribute cations are relevant to this paper only to Roozendaal (1996) concluded: "The find-

information (Zajonc, 1980; Mitchell and the extent of the closeness of the relation- ings of our studies using human subjects

Olson, 1981; Shimp, 1981; Zajonc and ship between memory and affect in adver- are consistent with those of our other

Markus, 1982; Srull, 1983, 1990; Stuart, tising, relative to cognition, and then de- studies using animal subjects in indicating

Shimp, and Engel, 1987; Batra and Ray, cision-making. If Damasio is correct that that fnemory storage is influenced by ac-

1986; Janisewski and Warlop, 1993). decision-making is primarily affective, tivation of p-adrenergic systems and the

Moving from advertising inputs to be- then those aspects of advertising and amygdala. Considered together, these

havior, Damasio (1994) suggested that de- memory deserve more attention. findings provide strong evidence support-

cision-making is primarily associated with The main research, on which we build, ing the hypothesis that the amygdala, es-

the part of the brain that deals with feel- is from CahiU and associates at the Uni- pecially the basolateral nucleus, plays a

c^tral role in modulating the consolida-

tion of long-term memory of emotionally

arousing experiences." In the final and

_,, Neo-cortex

Frontal tobes crucial study, Cahill et ai. (1996) showed

^^ two videos, each with 12 film clips, to

eight subjects. The more emotionally

arousing films were significantly {p < 0.05)

.better recalled than the emotionally neu-

tral videos three weeks after viewing. Fur-

thermore, the increased recall for the emo-

tionally arousing videos was correlated

with increased activation of the right

Ventro-mcdial _, amygdala, as indicated by positron emis-

frontal lobes sion tomography (PET),

Hypo

Memory, in the advertising literature,

has been tested with recognition and re-

Amygdala call measures though their value has been

subject to debate. Day-after recall (DAR)

may penalize affective ads as DAR is cog-

nitively biased (Zielske, 1982) or, con-

Rgure 1 Brain Locations 'Vic amygdala, or amygdaloid complex, functions as the

Kiimkl. Schuiirlz. nmt /.ssi'/J, 1991 gateway to and from affect'av memory.

2 6 JOURnRL Of March . Apm 1999

AD MEMORY

versely, emotive ads are better recalled • |3-blocker intervention is likely to re- ties. Those that penietrate at all trigger

(Thorson and Friestad, 1989). Dubow move that advantage of affective ads. memory. "Filters" account for the thresh-

(1994) proposed that recall has a thresh- old effects measured by DAR (Dubow,

old, nonlinear relationship with sales, i.e., Using the marketing and neuroscience 1994). Within tbat, the effecti\'eness of the

recall beyond the threshold or additional literature cited above, we propose a model advertising grows where affect is aroused

recall yields no benefit. It is thus necessary (Figure 2) which emphasizes memory (us- and, then, cumulatively, cognition. The

but not sufficient. He suggested that recall age experience, habit, brand and advertis- nesting shown in Figure 2 implies sigrufi-

be rehabilitated as an indicator of ad in- ing memories) as not only the key influ- cance, not sequence. Attitudes and beliefs

trusiveness. Recall and recognition, ence on buying beha\'ior but the temporal (memory) influence all stages of inbound

though correlated, are not unidimensional link between ad input and buying occa- processing; and information, supporting

{Finn, 1992; du Plessis, 1994). Recognition sions. Within that, affect dominates cogni- beliefs, is more readily accepted and re-

is more sensitive and discriminating than tion. In other words, affect may be enough merfibered (for o\'er\'iews of the attitudes

recall and diminishes with time (Singh, to modify memory and thence behavior, literature see, inter alios, Johnson, 1991;

Rothschild, and Churchill, 1988). but cognition comes into play when affect Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Olson and

A complicating factor in advertising re- is inconclusive. Modifying the earlier no- Zanna, 1993).

search has been the endemic bias toward tation, this can be expressed as M D A D C This model does not distinguish the

the cognitive (Vakratsas and Ambler, (or "MAC"). Memory, in flie broad sense various stages of memory beyond short

1999). Most of the processes of briefing used here, sets the context for, decision and long term. In practice, for advertising'

agencies, researching consumers, and ana- making. Within memory, the area of the effects to survive, i.e., reach long-term

lyzing the reports are cognitively ex- brain concerned with (social) feelings is memory, several processing stages are re-

pressed—each stage of which is cognitive involved, but thinking (cognition) is not quired (Rose, 1993).

and thereby tends to reduce the relative always essential (mere exposure theories). Both before and after the advertising

appearance of affective aspects. At the input stage, ads fight for atten- stimulus, behavior moderates perceptual

Holbrook, O'Shaughnessy, and Bell tion with other stimuli and competitive filters (buying a car makes one more likely

(1990) integrated competing marketing ads. Filters ensure that most potential per- to notice an ad for that car). Behavior is

schools of thought into "An Integrative ceptions do not engage our mental facul- also processed in short-term memory and

Overview of the Consumption Experi-

ence" with three types of component: rea-

sons (thoughts, intention), emotions

(wants, appreciation), and memory (habit, A MAC Model of Advertising

reinforcement, experience). Usage rein-

Ads

forced the emotional components which, Memory

niters

in turn, acted on the rational and habit Affect

Competitors

components which drove acquisition. At Cognition

for Attention Long

the same time, thoughts and wants,

looped with emotions, also moderated Term

reasons. Memory

From the literature we conclude:

Memory

Decision

f

Stimulus

i Affect

Decision-making may be more linked Ct^ltlon

with affect than cognition. Behavior

Affective ads are likely to be better re- New

called. . Information

Better memory is likely to correlate, at

least up to Dubow's threshold, with ad

effectiveness. Figure 2 A Tentative Model of Advertising Effects

April 1999 JOURfllll Of 27

AD MEMORY

thereby modifies brand equity (brand and level of entertainment to an educa- practitioner before deciding to take part,

memories). tional TV program. The ad blocks, at ap- ethical considerations had been covered.

A partial test of this model considers proximately 8 to 11 and 19 to 22 minutes, Recall,' recognition, and emotion mea-

just the relationship between ad affect and resembled regular commercial breaks. sures were obtained as follows. Immedi-

ad memory: the linkage between affect Four well-known (U. K.) brands, all fre- ately after viewing the video, the subjects

and recognition-and-recall. In focusing on quently purchased goods and services, were asked a series o^«questions (Day 1)

affect, we are not suggesting that cogni- were selected on a convenience basis: a about the ads and the background mate-

tive appeals are unimportant, merely that fast-food restaurant (FFR), a retail bank, a rial. They were required to list the brands

the literature indicates that affect plays a beer, and an oil company. Two ads were and goods advertised and the story line of

key role in memory formation, and ad rec- acquired for each brand. To minimize any any four of the advertisements shown (out

ognition and recall are long-used mea- primacy/recency effects, two versions of of a possible eight), describing the main

sures of that. the video were made with the pairs points shown in the background material.

- These advertising and neuroscience reversed. One recall measure was the number of A

streams of literature, and our model de- The ads were selected from a range of and C ads which made up the four cor-

rived therefrom, together provide four hy- possibles by an expert panel and pre- rectly identified. The Objects were not

potheses: screened by a 20-person (16 female and 4 given any feedback on their performance.

male, ages 25 to 53) control group which Twenty-four hours later (Day 2) the

HI: Advertisements with high affective received no pharmacological intervention subjects were shown 1(K) still images taken

components will have better reaiU fol- (controls). The controls tested the protocol from the video they had seen on Day 1.

lowing a single presentation. (no changes were needed) and also served The images were 12 x 16 cm., consisted of

H2: Advertisements with high affective to increase the number of non p blocker 256 colors, and were displayed on a com-

components will have better recogni- subjects. puter monitor. Ten images were selected

tion following a single presentation. Each subject viewed one version of the from each of the eight ads, and twenty

H3: Pharmacological treatments O- video assigned by a random design. Be- images were selected from the back-

blockers), applied before viewing, fore viewing the video (Day 1) the subjects ground material. Each image was dis-

will reduce the differences between were asked to complete a medical and de- played for 1 second on the monitor, in a

affective and cognitive advertisement mographic questionnaire. The various random order, with a fixed inter-stimulus

recall. questionnaires used are consolidated as interval of 10 for image recognition and 20

H4: Pharmacological treatments (p- an Appendix. Eighteen sif>jects (twelve seconds for image free-recall. Half of the

blockers), applied before viewing, female and six mal^ same age range) each images were shown with 10-second inter-

will reduce the differences between received either 40 mg. of Propranolot dis- vals (5 from each of the ads and 10 from

affective and cognitive advertisement solved with black currant juice or a pla- the background^ material) and the subjects

recognition. cebo (black currant juice only) 40 minutes were asked to indicate, by ticking a box on

before watching the video. Subjects, ran- the questionnaire, where they had seen

domly assigned, were unaware of which the image (either in the background ma-

METHODOLOGY

treatment they had received and of the terial or from one of the four companies).

The experiment had a two (low/high af-

purpose of the experiment. They were in- Subjects then recorded what happened in

fect ads) by two (placebo/p blocker) de-

structed not to make written notes but to the story line of the ad immediately after

sign. We tested affective ad content as the

relax and watch the video as if they were each of the remaining images, shown at

independent variable on recall and recog-

watching television in their own homes. 20-second intervals. The maximum score

nition, moderated by the pharmacological

for image recognition and free-recall was

intervention. Subjects viewed a video con- We considered the ethical issues im- 5 for each ad.

sisting of a 24-minute university course, plicit in this methodology in discussion

referred to as the background material, with a medical doctor. Given the full in- After subjects had viewed all images,

and 6 minutes of advertisements sepa- formation provided to volunteers, pre- they were asked to rate how emotional

rated into two blocks of four TV ads. The screening for medical problems (Section A tjiey felt after viewing each ad. Different

background material concerned the ecol- of the Appendix) and our recommenda- subjects respond differently to the same

ogy of rain forests and was similar in style tion that they consult their own medical ads, at least so far as affect is concerned

28 or RBIieRTISIRG RESERRCR March • Apni 1 9 9 9

AD MEMORY

(Moore et al., 1995). The subjects, them- cebo subjects. On this basis, the two FFR, C images for both image recognition (p <

selves, thus categorized the ads into those Oil 1, and Bank 1 were allocated to the .001) and image free-recall (p < .02) b\' the

that were more or less emotional, rather cognitive (G) and the other four to the af- combined controls and placebo group,

than allowing other subjects to allocate the fective (A) group. thus supporting H2,

ads. The subject's predisposition for each In view of the small sample sizes, the This research design raises the possibil-

of the brands was also recorded. (See the results for the controls have been merged ity that responses to the Day 1 question-

Appendix for questionnaires and scales.) with those from the placebo group to gi\'e naire biased responses on Day 28. There

In order to assess longer term recall, the a broader statistical base for the non p is correlation between Day 1 and 28 recaU

subjects were sent surprise questionnaires blocker group. Therefore, the top half of ('' = 0.52). Neuroscience would expect

by mail approximately 3 to 4 weeks after Table 1 provides the results for HI and such a link since long-term memory is ro-

they had viewed the video, "Day 28 re- H2. Note that Day 1 and Day 28 recall bust. We note the potentialforbias under

call." The instrument was identical to the scores each add to 4: we scored which, of limitations.

Day 1 questionnaire and the measure of the first four recalled, belong to each The p biocker results are presented in

recall used was the number of A and C group. Limiting recall in this way could be thelowerhalf of Table 1 which shows that

ads, out of four, correctly identified. In all, thought to bias results toward top of mind the placebo group recalled, both for Day 1

10 subjects did not return the Day-28 but has the advantage that the stronger and Day 28, nearly twice the A ads rela-

questionnaire, leaving 14 controls, 7 pla- memories are more likely to be recorded. tive to C whereas the Propranolol group

cebo and 7 3 blocker subjects. We are concerned not with total recall but recalled A and C equally. The interaction

: the relative strength of A ads versus C. is significant atp = .036. This supports H3

RESULTS Within this, HI is supported by the sig- which requires recall of the A ads to be

The ads were divided into two groups of nificantly (p < .001) greater recall of A ads. significantly different from the cogniHve

four according to their emotional- Table 1 also shows significantly more A ads for the placebo group but not for the

ity/affect rating by the controls and pla- still images being correctly identified than Propranolol group.

\ H4- proposed that the difference be-

tween the image recognition of A and C

TABLE X • ads would be reduced by the use of Pro-

Responses {±SEM) of Subjects to Advertisements Differing in pranoioi. Although, as shown by Table i.

Affective Content ^^^^ proved to be the case (3.4 - 2.8 = 0.6

reduced to 3.3 - 3.1 = 0.2), and therefore

t-Value H4 was technically supported, it was for

Cognitive Ads Affective Ads df (paired Mests) p * e wrong reason- Most of the reduction

Ojnti^s/Ptacebo "'^^ '^"^ ^" " ''''^'' recognition of the C

'•• • ads by the Propranolol group for which

Emotion (1-7)* 1.8 ± 0.2 3.8 ± 0.3 28 8.1 0.001 ^ , . \^ , , ,

• " we have no explanation. The lack of sup-

...}^^I^.^^9!}S^....^:^.^^:^. 3.4 ± 0 . 1 28 4.0 0.001 p^.^ for the spirit of H4 may be due to the

Image free-recall (1-5) 1.0 ± 0 . 1 1.4 ± 0 . 1 28 2.6 0,02 small sample size or less affect may up-

Day 1 recall 1.4 ± 0 . 1 2.6 ± 0 . 1 28 4.9 0.001 weight cognitive factors.

Day 28 recall 1.4 ± 0.1 2.6 ± 0.1 20 4.8 0.001

DISCUSSION AND

^^^°!?! MANAGERiALiMPUCATIONS

Emotion (1-7)" .?:;?..T.P.i^...-. .?.:?..* .9..?. ^.....H. .9..9.9.^ 1"hese results for emoHon appear to be

Image recognition (1-5) 3.1 ± 0.2 3.3 ± 0.2 8 1.3 0.13 consistent with the neuroscience literature

'''imagefree-recall (1-5)^ 1-1 ± 9;1 ^ l"3 ± 0.2 8 0.9 0.38 *^^* ^^^^^' enhances long-term memory' of

- the ad. We did not test the effect of affec-

Day 1 recall 2 ± 0.2 2 ± 0.2 8 0 1

•• tive advertising or cognitive appeals on

....R^y 28 recall 2 ±0.3 2 ±0.3 6 0 1 ^^,,^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ attitudes, still less the

'Vie numbers in parentheses indicate the ranges of the measurement satlts. further effect on behavior. Thus the ex-

. March • April 1 9 9 9 JOURRRL OF ROenSIRB RCSERRCN 2 9

AD MEMORY

. . . affect Is sufficiently Important to merit ad agency should be thoroughly screened to match

stimuli across the truly independent di-

briefing, careful copy<4e«ting, and tracking as a specific mensions. We need to know, therefore,

the extent to which persuasion and in-

component of advertising. Not ail ads woHc the same volvement correlate universally, or at

least generally, with emotion and to

way, and the same ads wori( differentiy with different which salience is independent. This re-

search provided clues, but no more than

peopie. that, of such interactions.

The output stage is more difficult. Test-

ing intermediate effects would be likely to

periment tests only a small part of the needs to give careful consideration to how bias behavior, and vice versa, and con-

MAC model. Nevertheless it highlights ads are held, post exposure, in memory sumer choices requiring recall (e.g., when

the significance of affect in the way adver- and the rote of affect in achieving that. The telephoning an order) may have different

tising works. endemic nature of cognitive bias was mechanisms to those only requiring rec-

The Day 1 results confirmed that the af- noted in the marketing literature review ognition (e.g., when prompted by super-

fective ads were better recalled than the above. market displays). Further work is also

cognitive. It is possible that the responses needed to relate advertising with brand

on Day 1 influenced those three to four FUTURE RESEARCH memory changes. As Nedungadi (1990)

weeks later, but given the importance of Advertising inputs and consumer pur- points out, "in order to anticipate the ef-

longer term effects, we included the re- chasing or other brand behavior are not fects of external brand primes on choice

sults as part of the explorative nature of usually simultaneous: long-term brand, probabilities, it is necessary to have a de-

this research. and perhaps advertising, memories con- tailed understanding of both retrieval pro-

Recognition was significantly stronger nect the two. Future research needs to test cesses and the organization of brands in

for affective ads for controls and the pla- both the input (advertising) and output memory." One possibility, following

cebo group (H2), but the result for Pro- (behavioral) stages of the MAC model. brain-imaging work, is "double split chan-

pranolol (H4) was not definitive. Singh For the input stage, following Roths- nels." Conventional split-TV-cable chan-

et al. (1988) suggested that recognition child et al. (1988), modem brain-imaging nels and single-source data would be used

was a more sensitive discriminator than techniques would provide greater depth to track ad inputs and behayior compara-

recall, but this was not supported by these of understanding than simply 3-bIocking bly to Jones (1995) for half the subjects.

results. emotions. Affect covers a broad range of The intermediate effects would be mea-

emotions, feelings, and moods, each of sured for the other (matched) half.

The main implication for managers is

that affect is sufficiently important to which may be positive or negative, stron-

merit ad agency briefing, careful copy- ger or weaker. There are biases inherent in LIMITATIONS

testing, and tracking as a specific compo- respondents cognitively reporting affec- Limitations of the work presented here in-

nent of advertising. Not all ads work the tive experience (Wilson et al., 1989). Brain clude:

same way, and the same ads work differ- imaging would, for example, help identify

ently with different people. We are not where and when these biases are taking • Small sample sizes and laboratory con-

suggesting that affect should be the major, place. Fried et al. (1997), for example, ditions: While conventionally sized for

or even a major, component of all adver- found that the brain was recording stimuli work in the natural sciences, the phar-

tising nor that cognitive components are accurately even when the subjects were macological treatments inhibit wide-

unimportant. Furthermore, memory, af- denying them. scale testing. This study is exploratory.

fect, and cognition are broad labels for a We also need greater understanding of • Narrow methodology for screening and

variety of separate brain functions. Nev- the relationships between emotion, per- selecting ads: The possibility exists that

ertheless, the advertising development suasion, involvement, and salience. The some ad familiarity and/or unequal ad

process, where quantitative analysis may confounding discussion above indicates quality (effectiveness) may have biased

bias participants toward the rational. that ads used for this type of research results.

30 OF HDUERTISIIIG RESEflRCH March . April 1 9 9 9

AD MEMORY

• Subjects were both male and female. APPENDIX

Samples were not demographically nor

psychographically (lifestyle and person-

CONSOUDATED QUESTIONNAIRES

ahty) matched.

• Day 1 questions may have influenced

Day 28 recall. A. Medical questionnaire

1. We would not like to administer to any pregnant individuals; are you likely to be

We do not consider that these limitations pregnant soon or are you pregnant now?

significantly affected our findings. The 2. Do you suffer from asthma?

methodology was pre-post comparisons 3. Do you suffer from any adverse drug reactions?

with the same subjects. The Propranolol 4. Do you suffer from any allergies? '•

subjects significantly (p < 0.01) recognized 5. Have you ever suffered from heart disease?

the emotionality so that the division of ads 6. Would you be willing to take part in the study if you did not have to take Propranolol?

was valid for them. Taken in isolation, we

would not consider these results defini-

B. Demographic questionnaire

tive. On the other hand, they are consis-

tent with both the neuroscience (especially

Cahill et al.) and marketing literatures. In 1. What was your age on

short, ad recall and recognition, which are 2. Are you male or female?

widely accepted as necessary, but not suf- 3. What hand to you usually write with?

ficient, indicators of advertising effective- 4. Is English your first language?

ness, are impacted by the emotion in those 5. What is your nationality?

ads. 6. Do you drink alcohol regularly (more than 9 drinks a week)?

7. Do you smoke regularly?

8. Have you ever owned a car?

CONCLUSIONS 9. Have you ever owned a house?

If the use of cognitive processes to mea- 10. Are you currently employed?

sure recall discriminates against affect 11. What is your highest academic qualification?

(Zielske, 1982), then this clear impact of 12. How many years have you spent studying at a tertiary institution?

emotion on recall is the more significant. 13. Do you have any visual impairments?

One attraction of using pharmacological 14. Do you have any auditor^' impairments?

intervention (Propranolol) to block emo-

.1 " -

tions is that their effect is unambiguous. C. Preiiminary questionnaire

There has been growing interest in the

role of affect in advertising since Zajonc 1\ Please indicate whether the following companies/categories are familiar to you and

(1980), which may be accelerated by the whether you have seen them in print (such as in a magazine) or on television or video.

advances in neuroscience. Cartesian as-

sumptions about consumers as rational in-

formation processors seem to be increas- D. Day 1 questionnaire (aiso: Day 28 questionnaire)

ingly under challenge. At the same time,

we must be careful not to dismiss the im- 1. What were the companies/organizations advertising their products?

portance of cognition. We need to inte- 2, What brands were advertised?

grate memory, affective, and cognitive 3, Write down the story (order of events) of any four advertisements that were in the

processes into a single research stream, video presentation. Write about three to four sentences for each advertisement,

and the MAC model is offered in that 4. In a paragraph or so, describe the themes and the main points of the research carried

context. (E© out in the main body of the video presentation.

March • April 1 9 9 9 JDURIIHL OF HDUERTISIRG RESERRCH 3 i

AD MEMORY

APPENDIX

TIM AMBLER Is a Senior Fellow at London Business

(Continued) ' School. His executive level introduction to marketing.

Marketing from Advertising to Zen. was published in

E. Day 2 questionnaire

the Rnancfal Times Guide series. His researcd

interests Include measuring mat1<eting performance,

1. Where have you seen this image before? how advertising works, and relationship marketing. He

2. What happened immediately after this image was shown in the video? has recently published in the Journal of Marketing,

the Journal of Marketing Research, and the

F. Follow up questions • tr)temational Journal of Research in Marketing.

He was previously Joint Managing Director.

1. Had you seen any of the material from the video prior to watching it? If so, please Intemational Distillers and Vintners, and originally

indicate your level of certainty on a scale of 0 (never seen before) to 5 (definitely seen qualified as a Chartered Accountant with Peat,

before). Marwick. Mitchell and Co.

2. Please indicate how emotional you felt after watching each component of the video on

a scale of 1 (not emotional) to 7 (highly emotional). TOM BURNE works at the Babraham Institute. He

attended the University of New England .in ^mldale.

G. Htoasures of persuasion, involvement, salience, and predisposition j Australia, where he completed a first class honors

degree in Rural Science. After obtaining a University

Please select your response to the following questions from the list of answers provided. Fellowship and completing a Doctor of Philosophy in

Physiology, he then took up a post doctoral research

1. What impressions did you get about the brand? fellowship with Professor Steven Rose at tfie Open

University. UK. His research interests are broad,

(1) It really stood out as a high quality brand.

focusing mainly on neuroscience and behavior, in

(2) It stood out as being quite different from other brands.

which the majority of his publications can be found.

(3) It was not very different, but it did stand out a bit.

(4) It was much the same as most other brands and didn't stand out very much.

(5) It was the sort of brand you didn't notice and didn't stand out at all.

2. How much did you enjoy the advertisement? REFERENCES

(1) I watched it very closely as it was very appealing advertising.

(2) I watched it quite closely, because it was more appealing than other ads.

AAKER, DAVID A., DOUGLAS M. STAVMAN, and

(3) I watched it quite closely, although it had no more appeal than other advertising.

MICHAEL R. HACERrv. "Warmth in Advertis-

(4) I didn't watch it very closely, because it was less appealing than other advertising.

ing: Measurement, Impact and Sequence Ef-

(5) I made a point of not watching it, because it was not an appealing ad.

fects." journal of Consumer Research 12, 4

3. What impact did the advertisement have on you?

(1986): 365-81.

(1) It really stood out as different advertising.

(2) It stood out as being quite different from other advertising.

ALWITT, LI>JDA F., and ANDREW A. MircHELL.

(3) It was not very different, but it did stand out a bit.

(4) It was much the same as most other advertising and didn't stand out very much. "Introduction." In Psychological Processes and

(5) It was the sort of advertising you didn't notice and didn't stand out at all. Advertising Effects, Linda F. Alwitt and An-

4. How did you feel about the brand before watching the \'ideo? J drew A. Mitchell, eds. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum,

(1) It's the brand I prefer and I wouldn't really consider anything else. * 1985.

(2) It's one of the main brands I'd consider along with others.

(3) It's one I'd consider equally along with others. ADOLPHS, R., D.'TRANEL, HANNAH DAMASIO,

(4) It's not the first brand I'd think of, but 1 might consider it. and ANTONIO R. DAMASIO, "Impaired recogni-

(5) I wouldn't' really think of it. tion of emotion in facial expressions foUowing

(6) I would definitely not consider it at all. bilateral damage to the human amygdala."

, (7) I am not familiar with that brand. Nature 372, 6507 (1994): 669-72.

32 QF RDUEHTISinG RESEHHCH March • April 1 9 9 9

AD MEMORY

BATRA, RAJEVH, and MICHAEL L. RAY. "Affec- of Attitudes. Ft Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace )o- Consumer Beha\ ior." In Research in Consumer

tive Responses Mediating Acceptance of Ad- vanovich, 1993. Behavior. Stamford, CT: )A1 Press, 1990.

vertising." journal of Consumer Research 13, 2

(1986): 234-t9. FRIED, ITZHAK, KATHERINE A. MACDCI\ALD, and JANISZEWSKI, CHRIS, and LUK WARLOP. "The

CHARLES L: WILSON. "Single Neuron Activity Influence of Classical Conditioning Proce-

BiEL, ALEXANDER L. "Love the Ad. Buy the in Human Hippocampus and Amygdala dur- dures on Subsequent Attention to the Condi-

Product? Why Liking the Ad\ ertisement and ing Recognition of Faces and Objects." Neuron tioned Brand." journal of Consumer Research 20,

Preferring the Brand Aren't Strange Bedfel- 18, 5 (1997): 753-65. 2 (1993): 171-89.

lows After All." Admap. September 26, 1990.

GIBSON, LARRI' D. "Not Recall." journal of Ad- JOHNSON, BLAIR T. "insights About Attitudes:

CAHILL, LARRY, BRUCE PRINS, MICHAEL WEBER, vertising Research 23, 1 (1983): 39-16. Meta-analytic Perspectives." journal of Person-

and JAMES L. MCGAUGH. "P-Adrenergic activa- ality and Social Psychology 17, 3 (1991): 289-

tion and memory for emotional e\'ents." Na- GREENBLATT, D. )., j . M. SCAVONE, J. S. HAR- 99.

ture 371, 6499 (1994): 702-704. MATZ, N. ENGELHARDT", and .R. L SHADLR. "Cog-

nitive effects of beta-adrenergic antagonists

JONES, JOHN P. "Advertising: Strong Force or

after single doses—pharmacokinetics and

, RALF BABINSKY, HA>JS J. MARKOWITSCH, Weak Force? Two \ iews an ocean apart." In-

pharmacodynamics of propranoioi, atenolot,

and JAMES L. MCGAUGH. "The amygdala and ternational journal of Advertising 9, 3 (1990):

lorazepam and placebo." Clinical Pharmacology

emotional memory." Nature 377, 6547 (1995): 233-46.

and Therapeutics 53, 5 (1993): 577-84.

295-96. ;

. When Ads Work. New York: Lexington

GREWAL, DHRLV, SUKLMAR KA\ ANOOR, EDWARD

, RICHARD J. HAIER, JAMES FALLON, Books, 1995.

F. FERN, CAROLYN Ccie^TLEV, and JAMES BAR.\ES.

MICHAEL T, ALKIRE, CHEUK TANG, DAVID

"Comparative Versus Noncomparative Adver-

KEATOR, JOSEPH WU, and JAMES L. MCGAUGH. JOYCE, TIMOIHY. "Models of the Advertising

tising: A Meta-Analysis." lournal of Marketing

"Amygdala activity at enccsling correlated Process?" Marketing and Research Today 19

61, 4 (1997): 1-15.

with long-term, free-recalt of emotional infor- (1991): 205-13.

mation." Proceedings of the National Academy of

1., and

Science USA 93,15 (1996): 8016-21. KANDEL, ERIC R., JAMES H . SCHWARTZ, and

"The ARF Copy Research Validity Project."

THOMAS M. JESSELL, eds. PrincipJes of Neural

Journal of Advertising Research 31, 2 (1991): 11-

CHILDERS, TERRY L., and MiCHArL ). HOUSTON. Science. Non^ alk, CT: Appleton and t^nge,

,32.

"Conditions for a Picture-Superiority Effect on 1991.

Consumer Memory." journal of Consumer Ke-

HAMAN\, S. B., L. CAHILL, and L. R. Sc

s^nrdi 11, 2 (1984): 643-54. ^ \ " LEDOLX, JOSFPH E. "Emotion, Memor\' and the

"Emotional perception and memory in amne-

sia." Neurophysiology 11, 1 (1997); 104-13. Brain." Scientific American, June 1994.

X •••

DAMASIO, ANTONIO R. Descartes' Error: Emotion,

HOLBRtXiK, MORRIS B. "Emotion in the Con- LooiSH, LEONARD M., MAGID ABRAHAM, STLART

Reason and the Human Brain. London: Paper-

sumption Experience: Toward a New Model KALMENSON, JEANNE LIVELSBERGER, BETH LLBET-

mac (Macmillan), 1994.

of the Human Consumer." In The Role of Af- KiN, BRUCE RICHAR[»ON, and MARY ELLEN

DuBOW, JOEL S. "Point of View: Recall Revis- fect in Consumer Bchni'ior: Emerging Theories STE\ ENS. "How Advertising Works: A Meta-

ited: Recall Redux." journal of Advertising Re- and Applications. Robert A. Peterson, Wayne Analysis of 389 Real World Split Cable TV

search 34, 3 (1994): 92-106. . D. Hoyer, and William R. Wilson, eds. Lex- Advertising Experiments." Journal of Marketing

ington, MA: Lexington Books, 1986. Research 32, 2 (1995): 125-39.

DU PLESSIS, ERIK. "Recognition versus Recall."

journal of Advertising Research 34, 3 (1994): 75- HOLBROOK, MORRIS, B., JOHN O'SHAUGHNESSY, MCGALGH, JAMES L., LARR'I CAHILL, and

91. • ' ^. and STEPHEN BEI L. "Actions and Reactions in BENNO ROOZENDAAL. "invoKement of the

the Consumption Experience: The Comple- amygdala in memory storage: Interaction with

EAGLY, A. H., and S. CHAIKEN. Tlie Psychology mentary Roles of Reasons and Eqiotions in other brain s^'stems." Proceedings of the Na-

March . April 1 9 9 9 JOURRRL OFflDUERTISIR6RESEDRCIJ 3 3

AD MEMORY

tional Academy of Science USA 93, 24 (19%): ries and Applications. Robert A. Peterson, . Processing Perspective." In Emotion in Adver-

13508-14. Wajme D. Hoyer, and William R. Wilson, eds. tising. Stuart J. Agres, Julie A. Edell, and Tony

Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1986. M. Dubitsky, eds, Westport, CT: Quorum,

MALONEY, JOHN C. "Consumer Psychology's 1990.

Potential Contribution to Social Science." In PHELPS, ELIZABETH A., and ADAM K. ANDER-

Emotion in Advertising. Stuart J. Agres, Julie A. SON. "Emotional memory: What does the STUART, ELNORA W., TERENCE A. SHIMP, and

Edell, and Tony M. Dubitsky, eds. Westport, amygdala do?" Current Biology 7, 5 (1997): RANTJALL W. ENGEL. "Classical Conditioning

CT: Quorum Books, 1990. R311-R314. of Consumer Attitudes: Four Experiments in

an Advertising Context." journal of Consumer

MITCHELL, ANDREW A., and JERRY C. OLSON. ROSE, STEVEN P. R. The Making of Memory. Lon- Research 14, 3 (1987): 334-49.

"Are Product Beliefs the Only Mediator of don: Bantam Books, 1993.

Advertising Effects on Brand Attitude?" jour- THORSON, ESTHER, and M. FRIESTAD. "The Ef-

ml of Marketing Research 18, 3 (1981); 318-32. ROTHSCHILD, MICHAEL L., and YONG J. HYUN. fects of Emotion on Episodic Memory for

"Predicting Memory for Components of TV Television Commercials." In Cognitive and Af-

MOORE, DAVID J., W[LLiA.y D. HARRIS, and Commercials from EEG." }ournal of Consumer fective Responses to Advertising. P. Cafferata

HofiG C. CHEN. "Affect Intensit)': An Indi- Research 16, 4 (1990): 472-78. and A. Tybout, eds. New York: Lexington

vidual Difference Response to Advertising Books, 1988.

Appeals." journal of Consumer Research 22, 2 , BYRON REEVES, ESTHER THORSON, and

(1995): 154-64. ROBERT GOLDSTEIN. "Hemispherically Lateral- VAKRATSAS, DEMETRIOS, and TIM AMBLER.

ized EEG as a Response to Television Com- "How Advertising Works: What Do We Real-

NEDLNGADI, PRAKASH. "Recall and Consumer mercials." journal {^Consumer Research 15, 2 ly Know?" journal of Marketing 63,1 (1999):

Consideration Sets: Influencing Choice with- (1988): 185-98. 26-43.

out Altering Brand Evaluations." journal of

Consumer Research 17, 3 (1990): 263-76. SHIMP, TERENCE A. "Attitude Toward the Ad WELSON, TIMOTHY D., DANA S. DUNN, DOLORES

as a Mediator of Consumer Brand Choice." KRAFT, and EJOLGLAS J. LISLE. "Introspection,

OLSON, JAMES M., and MARK P. ZANNA. "Atti- journal of Advertising 10, 2 (1981): 9-15. Attitude Change, and Attitude-Behavior Con-

tudes and Attitude Change." Annual Review of sistency: The disruptive effects of explaining

Psychology 44 (1993): 117-54. SiNGH, SURENDEW N . , MiCHAEL L. ROTHSCHlLD, why we feel the way we do." Advances in Ex-

and GILBERT A. CHURCHILL, JR. "Recognition perimental Social Psychology, 22, Leonard

Y, JOHN. Explaining Buyer Behav- Versus Recall as Measures of Television Com- Berkowitz, ed. New York: Academic Press,

ior. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. mercial Forgetting." journal of Marketing Re- 1989.

search 25, 1 (1988): 72-80.

PERCY, LARRY, and JOHN R. RossriER. "A ZAIONC, ROBERT B. "Feeling and Thinking."

Theory-Based Approach to Pretesting Adver- SROLL, THOMAS K. "Affect and Memory: The American Psychologist 35, 2 (1980): 151-75.

tising." In Measuring Advertising Effectiveness. impact of affective reactions to advertising on

WUiiam D. Wells, ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, the representation of product information in , and HAZEL MARKUS. "Affective and •

1997. memory." In Advances in Consumer Research. Cognitive Factors in Preferences." journal of

R. P. Bagozzi and A. Tybout, eds. Ann Arbor, Consumer Research 9, 2 (1982): 123-31.

PETERSON, ROBERT A., WAYNE D . HOYER, and MI: Association for Consumer Research, 1983.

WILLIAM R. WILSON. "Reflections on the Role ZiELSKE, HUBERT A. "Does Day-After-Recall

of Affect in CcMisumer Behavior." In The Role . "Individual Responses to Advertising: Penalize 'Feeling' Ads?" journal of Advertising

of Affect in Consumer Behavior: Emerging Theo- Mood and Its Effects from an Information Research 22,1 (1982): 19-22.

3 4 JOURRRL OF ROOERTISIRB March . April 1 9 9 9

View publication stats

You might also like

- Anxiety DisordersDocument37 pagesAnxiety DisordersDr Dushyant Kamal Dhari75% (4)

- Your Anxious BrainDocument45 pagesYour Anxious BrainAnksioznost Depresija100% (4)

- Brain BombDocument45 pagesBrain Bombmasterzpf100% (1)

- A Philosophy of Fear of FearDocument157 pagesA Philosophy of Fear of Feartracylyp100% (6)

- Structure and Function of The Brain - Boundless PsychologyDocument27 pagesStructure and Function of The Brain - Boundless PsychologyAhmad Badius ZamanNo ratings yet

- AnxietyDocument41 pagesAnxietymayshiaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence - Business-Case-2016 PDFDocument65 pagesEmotional Intelligence - Business-Case-2016 PDFImad MukahhalNo ratings yet

- Visual Masking: Studying Perception, Attention, and ConsciousnessFrom EverandVisual Masking: Studying Perception, Attention, and ConsciousnessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- What Is NeuromarketingDocument6 pagesWhat Is Neuromarketingirenek100% (5)

- Cambridge IGCSE Environmental Management Coursebook PDFDocument50 pagesCambridge IGCSE Environmental Management Coursebook PDFantra v33% (9)

- Reconsidering Recall and Emotion in AdvertisingDocument9 pagesReconsidering Recall and Emotion in AdvertisingAnna Tello BabianoNo ratings yet

- Detection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationFrom EverandDetection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationArthur MacNeill Horton, Jr.No ratings yet

- Sts Cheat Sheet of The BrainDocument30 pagesSts Cheat Sheet of The BrainRahula RakeshNo ratings yet

- Presentation Employee EngagementDocument9 pagesPresentation Employee Engagementantra vNo ratings yet

- Hansen (2003) Distinguishing Between Feelings and Emotions in Understanding Communication EffestsDocument11 pagesHansen (2003) Distinguishing Between Feelings and Emotions in Understanding Communication EffestsmarkolovNo ratings yet

- Ad Brand Congruity ScaleDocument10 pagesAd Brand Congruity Scaleantra vNo ratings yet

- Non Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsDocument20 pagesNon Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsRameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Emotional AdertisingDocument47 pagesThe Impact of Emotional Adertisingboris_sovNo ratings yet

- The Emotionally Charged Advertisement and Their Influence On Consumers' Attitudes"Document14 pagesThe Emotionally Charged Advertisement and Their Influence On Consumers' Attitudes"Shazia AllauddinNo ratings yet

- An Empirical Investigation of The Differential EffectsDocument424 pagesAn Empirical Investigation of The Differential EffectsEureka KashyapNo ratings yet

- Neuro y MusicaDocument4 pagesNeuro y MusicaJaviNo ratings yet

- The Role of Emotions in Advertising A Call To ActionDocument11 pagesThe Role of Emotions in Advertising A Call To ActioneliNo ratings yet

- Explaining The Special Case of Incongruity in AdveDocument33 pagesExplaining The Special Case of Incongruity in Advequinnacai87No ratings yet

- Ruchika - Ohme 2010 JEP - EEG - Asymmetry - AdvResearchDocument9 pagesRuchika - Ohme 2010 JEP - EEG - Asymmetry - AdvResearchAishwarya NairNo ratings yet

- Artículo NeuromarketingDocument11 pagesArtículo NeuromarketingARANZA ROSALES ALARCONNo ratings yet

- Foa - Kozak 1986 - OPTIONALDocument16 pagesFoa - Kozak 1986 - OPTIONALCarla MariaNo ratings yet

- Elements of The Socratic Method - II - Inductive ReasoningDocument11 pagesElements of The Socratic Method - II - Inductive Reasoningdrleonunes100% (1)

- Applications of Evolutionary Psychology in Marketing: Gad SaadDocument30 pagesApplications of Evolutionary Psychology in Marketing: Gad SaadYàshí ZaNo ratings yet

- 10 1108 - Apjml 04 2019 0231 PDFDocument20 pages10 1108 - Apjml 04 2019 0231 PDFnicolas garzonNo ratings yet

- RP 3Document7 pagesRP 3PulkitNo ratings yet

- BrewinDocument20 pagesBrewinMelina VillalongaNo ratings yet

- AjzenDocument17 pagesAjzendaroshdyNo ratings yet

- 1995 Nida PettyDocument9 pages1995 Nida PettyAaditya BaidNo ratings yet

- Re InquiriesDocument13 pagesRe InquiriesVibhav SinghNo ratings yet

- NEUROCIENCIA DEL CONSUMIDOR - Plassmann - Karmarkar - HBoCP - 2015Document29 pagesNEUROCIENCIA DEL CONSUMIDOR - Plassmann - Karmarkar - HBoCP - 2015Lark LovelaceNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of AdvertisingDocument19 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of Advertisingsunny nasaNo ratings yet

- Neuromarketing - A Step Ahead of Traditional Marketing ToolsDocument7 pagesNeuromarketing - A Step Ahead of Traditional Marketing ToolsAHMET ŞENLERNo ratings yet

- Age-Related Differences in Responses To Emotional AdvertisementsDocument12 pagesAge-Related Differences in Responses To Emotional AdvertisementsYa YaNo ratings yet

- 1989 Eich & Metcalfe 1989 Mood Dependent Memory For Internal Versus External EventsDocument13 pages1989 Eich & Metcalfe 1989 Mood Dependent Memory For Internal Versus External EventshoorieNo ratings yet

- Unconscious Mood-Congruent Memory Bias in DepressionDocument9 pagesUnconscious Mood-Congruent Memory Bias in DepressionNetzwerk KarenNo ratings yet

- 3 - Exploring Childrenâ S Choice The Reminder Effect of ProductDocument17 pages3 - Exploring Childrenâ S Choice The Reminder Effect of ProductarayaNo ratings yet

- Positive Autobiographical Memory Retrieval Reduces Temporal DiscountingDocument10 pagesPositive Autobiographical Memory Retrieval Reduces Temporal DiscountingAdrienn MatheNo ratings yet

- The Paranoid Optimist An Integrative EvolutionaryDocument61 pagesThe Paranoid Optimist An Integrative EvolutionaryAngela MontesdeocaNo ratings yet

- Mindful Creativity: The Influence of Mindfulness Meditation On Creative ThinkingDocument2 pagesMindful Creativity: The Influence of Mindfulness Meditation On Creative ThinkingAnto MieleNo ratings yet

- Revision de 10 Años de MemoriaDocument15 pagesRevision de 10 Años de MemoriaUldæ GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Gender & Mood Effects On GenderDocument25 pagesGender & Mood Effects On GenderNikita HuddartNo ratings yet

- Marketing Stratagies of Bajaj AutomobilesDocument89 pagesMarketing Stratagies of Bajaj Automobilespinkirozario100% (1)

- Need For Cognition and Advertising: Understanding The Role of Personality Variables in Consumer BehaviorDocument23 pagesNeed For Cognition and Advertising: Understanding The Role of Personality Variables in Consumer BehavioralimnaqviNo ratings yet

- Customer's Perception: Consumer PerceptionsDocument25 pagesCustomer's Perception: Consumer PerceptionsDipin NambiarNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Association For Psychological ScienceDocument6 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Association For Psychological Sciencesyedfaysal-2018026597No ratings yet

- 6 Plassman Etal IJA 2007Document25 pages6 Plassman Etal IJA 2007edNo ratings yet

- How To Measure Cerebral Correlates of Emotions in Marketing Relevant TasksDocument16 pagesHow To Measure Cerebral Correlates of Emotions in Marketing Relevant TasksJE ACNo ratings yet

- On The Relationship Between Recall and Recognition Memory: Frank Haist Arthur P. ShimamuraDocument12 pagesOn The Relationship Between Recall and Recognition Memory: Frank Haist Arthur P. ShimamuraAaron SylvestreNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Negative Experiences Without Ruminating The Role of Self-Distancing in Enabling Adaptive Self-ReflectionDocument14 pagesAnalyzing Negative Experiences Without Ruminating The Role of Self-Distancing in Enabling Adaptive Self-Reflection12traderNo ratings yet

- Brandingthebrain AcriticalreviewandoutlookDocument20 pagesBrandingthebrain AcriticalreviewandoutlooklauNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Emotional Cues On Prospective Memory A Systematic Review With Meta AnalysesDocument20 pagesThe Influence of Emotional Cues On Prospective Memory A Systematic Review With Meta AnalysesfarizNo ratings yet

- Affect Labelling and ExposureDocument13 pagesAffect Labelling and Exposuredotame7986No ratings yet

- Marketing Sensorial Personificación y Cognición Fundamentada - Una Revisión e IntroducciónDocument10 pagesMarketing Sensorial Personificación y Cognición Fundamentada - Una Revisión e IntroducciónPaiiulClavijoNo ratings yet

- Marketing Sensorial Personificación y Cognición Fundamentada - Una Revisión e IntroducciónDocument10 pagesMarketing Sensorial Personificación y Cognición Fundamentada - Una Revisión e IntroducciónPaiiulClavijoNo ratings yet

- Allen2010 2Document10 pagesAllen2010 2UrosNo ratings yet

- Neuromarketing ESSAY Adriana Bianchi PDFDocument7 pagesNeuromarketing ESSAY Adriana Bianchi PDFAdriana BianchiNo ratings yet

- Consumer NeuroscienceDocument21 pagesConsumer Neurosciencejuanitocomprador1952No ratings yet

- A New Model For Measuring Advertising EffectivenessDocument10 pagesA New Model For Measuring Advertising EffectivenessShahriar AziziNo ratings yet

- Converging Cognitive Enhancements: Anders Sandberg and Nick BostromDocument27 pagesConverging Cognitive Enhancements: Anders Sandberg and Nick BostromfsandowNo ratings yet

- 12 Anuvinda P4Document7 pages12 Anuvinda P4Anuvinda ManiNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 04 00639Document11 pagesFpsyg 04 00639msNo ratings yet

- Experimental Psychology Experiment Proposal Working Title: ExperimenterDocument5 pagesExperimental Psychology Experiment Proposal Working Title: ExperimenterZymon Andrew MaquintoNo ratings yet

- Exposure Therapy: Rethinking the Model - Refining the MethodFrom EverandExposure Therapy: Rethinking the Model - Refining the MethodPeter NeudeckNo ratings yet

- Psychophysiological assessment of human cognition and its enhancement by a non-invasive methodFrom EverandPsychophysiological assessment of human cognition and its enhancement by a non-invasive methodNo ratings yet

- Is India A Soft NationDocument2 pagesIs India A Soft Nationantra vNo ratings yet

- Rahulrp 2Document1 pageRahulrp 2antra vNo ratings yet

- Cancer Advertisement ScaleDocument1 pageCancer Advertisement Scaleantra vNo ratings yet

- Ad BrandDocument9 pagesAd Brandantra vNo ratings yet

- Buchholz 1991Document15 pagesBuchholz 1991antra vNo ratings yet

- AdBrandCongruityScale PDFDocument1 pageAdBrandCongruityScale PDFantra vNo ratings yet

- WeyandtDocument408 pagesWeyandtAntonella María De Jesús Napán CarbajalNo ratings yet

- (CITATION Sar11 /L 1033) : 1. James - Lange TheoryDocument5 pages(CITATION Sar11 /L 1033) : 1. James - Lange TheorySHINGYNo ratings yet

- Encoding-Retrieval Similarity and MemoryDocument48 pagesEncoding-Retrieval Similarity and Memorydsekulic_1No ratings yet

- Illuminating The Aura of Nostalgia: Perceptions of Time, Place, and Identity (ANASTASIA PLATOFF)Document33 pagesIlluminating The Aura of Nostalgia: Perceptions of Time, Place, and Identity (ANASTASIA PLATOFF)Anastasia PlatoffNo ratings yet

- Richard Et Al., (2022) Revisión de EstudiosDocument13 pagesRichard Et Al., (2022) Revisión de EstudiosAlicia BANo ratings yet

- Triune Brain TheoryDocument3 pagesTriune Brain TheorybambBoo777100% (1)

- Natalie Stallard EssayDocument12 pagesNatalie Stallard EssayNATALIE STALLARDNo ratings yet

- Neuromudalação ECTDocument13 pagesNeuromudalação ECTCamila BeloNo ratings yet

- CAIE Psychology A-Level: Biological Approach: Case StudyDocument7 pagesCAIE Psychology A-Level: Biological Approach: Case StudyNeda ElewaNo ratings yet

- Pranayamas and Their Neurophysiological EffectsDocument10 pagesPranayamas and Their Neurophysiological EffectsPuneeth RaghavendraNo ratings yet

- Fear Extinction and Emotional Processing Theory: A Critical ReviewDocument17 pagesFear Extinction and Emotional Processing Theory: A Critical ReviewGustavoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Sciences 2nd Edition Sobel Test Bank DownloadDocument6 pagesCognitive Sciences 2nd Edition Sobel Test Bank DownloadRicardo Rivera100% (26)

- Lecture 12 - Memory The Physiology of The Senses: WWW - Tutis.ca/sensesDocument17 pagesLecture 12 - Memory The Physiology of The Senses: WWW - Tutis.ca/sensesMihaela CenușeNo ratings yet

- Study Guide For EXAM 3Document19 pagesStudy Guide For EXAM 3Alex JingNo ratings yet

- Depersonalization Disorder A Functional NeuroanatomicalDocument9 pagesDepersonalization Disorder A Functional NeuroanatomicalyochaiatariaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Psych On The MachinistDocument21 pagesCognitive Psych On The MachinistRahul CharnaNo ratings yet

- Sasser Gender Differences in LearningDocument5 pagesSasser Gender Differences in LearningVedran GaševićNo ratings yet

- Grieve - OKDocument11 pagesGrieve - OKRonaldo Morales GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Neurobio DSHDocument10 pagesNeurobio DSHamritaNo ratings yet

- Oxford Handbooks Online: Understanding Anxiety Disorders From A "Triple Vulnerability" FrameworkDocument36 pagesOxford Handbooks Online: Understanding Anxiety Disorders From A "Triple Vulnerability" FrameworkhaleyNo ratings yet

- Integrative Functions of The Nervous SystemDocument18 pagesIntegrative Functions of The Nervous Systempuchio100% (1)

- Mari Book FullDocument32 pagesMari Book Fullsiraaey noorNo ratings yet