Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Power relations in qualitative research

Uploaded by

Rema VanchhawngOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Power relations in qualitative research

Uploaded by

Rema VanchhawngCopyright:

Available Formats

Power

Power relations in qualitative research: Qualitative inquiry draws on a critical view

of hierarchical relations of power between researchers and participants: “In traditional

research, the roles of researcher and subject are mutually exclusive: the researcher alone

contributes the thinking that goes into the project, and the subjects contribute the action or

contents to be studies”.

The study of power relations between researcher and participants, as any analysis of

power, should go beyond the normative and rhetoric level and be grounded on the real

practices of qualitative research.

Power relations during different stages of the research: The developmental nature of

the research process leads to changes in power relations, which pose specific ethical issues

to the researcher, five stages have been identified:

1. Initial stage of subject /participant recruitment: During this stage control over

the research process lies in the hand of the researcher, who decides how to

introduce the research to potential participants, how to describe the research

goals, and how to disclose, institutional affiliations to enlist maximum

cooperation. The amount and quality of the information offered regarding the

research are entirely at the researcher’s discretion. The goal of this stage is to

persuade potential participants to participate in the research and share their

personal experience and knowledge. The dependence of the researcher on the

participants consent might enable participants to obtain more information about

the research and the researcher. The researcher, who is in possession of the

information about the study, and the participants, who own the knowledge and

experience needed to perform the study, can use their respective powers to

negotiate the level of information provided about the study. This negotiation has

the potential to change the power relations between the two, going participant’s

greater power and more information. At this stage, ethical dilemmas involve

questions about strategically obscuring some of the research goals to persuade

the participants to take part in the study.

2. Data collection: During this stage, the researcher seems to be entirely

dependent on the participant’s willingness to take part in the research and to

share their knowledge of the research subject with the researcher. At this stage,

control and ownership of the data seem to be in the hands of the participants.

The quantity and quality of the data shared with the researcher depend in part

on the relationship that develops between the researcher and various

participants. The researcher must try to elicit the participants’ stories as much as

possible, their experiences, and their wealth of knowledge of the research topic.

There are various rapport building tactics that can be interpreted as a mask for

some type of manipulation or exploitation carried out to obtain the data needed

for the studies. These tactics include self-disclosure running errands, sharing a

meal, or falling friendship K Vale (1996) argued that the warm, caring and

empowering character of qualitative interviews might conceal huge power

differences, and the dialogue that takes place in the interviewing process might

be a cover for the exercise of power. From this perspective, most of the power

lies in the hands of the interviewer, who poses the research project, sets the

agenda, and rules the conversations. The idea of the researcher’s exclusive

power is only partially true, because the interviewees themselves can also

determine the level of cooperation in the discussion. For example, they can use

various problematic interviewee behaviours, they can shift the focus of the

conversation and they can ultimately decide to terminate the interview. In

biographical research, for example, the participant held maximum power and

control of the story during the data collection stage.

3. Data analysis and production of the report: With termination of the data

collection stage (or specifically the one-on-one interview), formal control and

power over the data returns to the researcher.

From now on, the story shared with the interviewer is “separated” from the

participant, and the researcher becomes the “storyteller” who recasts the story

into a “new” historical, political and cultural context.

During this stage, the researcher’s control over the data seems to be absolute

(i.e., the interviewers monopoly of the interpretation), and ethical considerations

are of utmost importance.

The researcher has total responsibility forward the participants the research

project, and the institution.

The willingness to share the data analysis process with participants or letting

them join in the final stages of writing is in the researcher’s hands.

The decision to share varies according to the researcher’s world view,

qualitative research paradigm, and the nature of the research content.

4. Validation: After data collection and analysis are completed, some

researchers choose to re-engage participants with the objective of strengthening

the trustworthiness accuracy, and validity of the findings, and to empower the

interviewers.

The re-engagement is implemented through follow-up interviews meant to

check the authenticity of emergency insights identified by researchers and

verification of participants intended meanings are member checking, carried out

individually or in a group, in which participants have the opportunity to discuss

the findings and conclusions of the study.

This process is meant to decrease the risk of misinterpretation of the

participant stories by providing inaccurate generalizations.

There are also different levels of involvement: Some researchers allow

participants to transcribe the interviews; others let them edit the transcripts.

Some prefer to present participants with the emerging themes; others prefer

presenting the final draft of the research. Some, for various reasons, prefer not

to get back to them at all. Every choice the researcher makes (to share or not to

share, when to share, and what to share) has inherent ethical difficulties.

Forbat and Henderson (2005) questioned the issue of allowing participants to

comment on their transcripts from the participant point of view.

They suggested that although sharing transcripts in the process, it can be

experienced as threatening; understanding speaker ungrammatical style and

prompting worry over how they are represented. Another problem that

participants might experience is the difficulty of confronting the researcher’s

analysis. Exposing the analysis to participants who lack adequate clinical skills to

deal with their re-actions to the findings, especially regarding sensitive issue, can

potentially cause harm.

5. Additional publications from the same source material: The use of research

data for additional research purposes seems to be the researcher’s prerogative.

This use can be made years after the data were collected, at a time when

participants are cut off from the researcher process.

This stage raises several questions from an ethical point of view, such as ‘to

whom do the data belong?-to the participants, the researchers, or the research

community?’

Even if the consent form signed by participants at the beginning of the

process grants some approval to dissiminate data, it is possible that participants

were not completely aware of the fact that their authorization amounts to a

complete renunciation of knowledge ownership to others.

In qualitative studies, this is especially true when unexpected data emerge

from the study that were not included in the original goals of the study and were

not specified in the consent form:

Figure: The flow of power relations in qualitative Researcher.

You might also like

- Participatory Action Research for Evidence-driven Community DevelopmentFrom EverandParticipatory Action Research for Evidence-driven Community DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Data CollectionDocument11 pagesQualitative Data CollectionDenny K.No ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Methods - CGSDocument66 pagesQualitative Research Methods - CGSRocky R. NikijuluwNo ratings yet

- Qualitative research methods for understanding patient experiencesDocument27 pagesQualitative research methods for understanding patient experiencesNayomi YviNo ratings yet

- Sample Chapter IIIDocument12 pagesSample Chapter IIIvjonard21No ratings yet

- Summary ADocument3 pagesSummary AAdara PutriNo ratings yet

- CTU Masteral Exercise 5 - November 4, 2023Document8 pagesCTU Masteral Exercise 5 - November 4, 2023Anything For YouNo ratings yet

- What Is Qualitative ResearchDocument6 pagesWhat Is Qualitative ResearchMaryJoyceRamosNo ratings yet

- Lecture 8: Process of Research What Is A Research Process? Select A TopicDocument4 pagesLecture 8: Process of Research What Is A Research Process? Select A TopicIshak IshakNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 ExampleDocument7 pagesChapter 2 ExampleMa. Alyzandra G. LopezNo ratings yet

- Revalida ResearchDocument3 pagesRevalida ResearchJakie UbinaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Review For Research Methods For EducationDocument27 pagesFinal Exam Review For Research Methods For EducationBella WeeNo ratings yet

- Understanding Qualitative Research MethodsDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Qualitative Research MethodsAlhsmar SayagoNo ratings yet

- RESA Final Preboard P1Document10 pagesRESA Final Preboard P1carloNo ratings yet

- Chapter Iii With Page Numbers Draft 3Document5 pagesChapter Iii With Page Numbers Draft 3AGLDNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document9 pagesChapter 3Janelle Anne ViovicenteNo ratings yet

- PracRes ReviewerDocument3 pagesPracRes ReviewerAljaira MarieNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Lecture Notes: Key CharacteristicsDocument2 pagesQualitative Research Lecture Notes: Key CharacteristicsErika Mae ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Saving Habits: Financial Literacy of Ann StudentsDocument9 pagesSaving Habits: Financial Literacy of Ann StudentsHeaven HaicyNo ratings yet

- Important Factors of Qualitative ResearchDocument1 pageImportant Factors of Qualitative ResearchMowti PangandamanNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research: Name: Mohd Amerul Akmal Bin Mohd Yunos: Syahidani Binti Mohamed: Nabilah Faiqah Binti AzmanDocument11 pagesQualitative Research: Name: Mohd Amerul Akmal Bin Mohd Yunos: Syahidani Binti Mohamed: Nabilah Faiqah Binti AzmanAmerul LeviosaNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research DesignDocument35 pagesQualitative Research Designkimemia100% (4)

- PR 1 Quantitative and QualitatativeDocument22 pagesPR 1 Quantitative and QualitatativeJasmin SerranoNo ratings yet

- 04 Practical Research 1 - Characteristics, Strengths and Weaknesses, Kinds, and Importance of ResearchDocument4 pages04 Practical Research 1 - Characteristics, Strengths and Weaknesses, Kinds, and Importance of Researchnievesarianne1No ratings yet

- PR1 Q1 ExamDocument7 pagesPR1 Q1 ExamShelvie Morata (Bebeng)100% (1)

- Chapter IiiDocument3 pagesChapter Iiikaycel ramosNo ratings yet

- Quantative Research Methods NotesDocument50 pagesQuantative Research Methods NotesNjeri MbuguaNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Qualitative Research MethodsDocument5 pagesCharacteristics of Qualitative Research Methodsshabnam100% (1)

- MRXH7Document4 pagesMRXH7dennis berja laguraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2Angelie LaurenNo ratings yet

- Physical Science ReviewerDocument6 pagesPhysical Science ReviewerAngelica CarreonNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 3 QualitativeDocument5 pagesCHAPTER 3 QualitativeChristian Jay AdimosNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector's Field GuideDocument13 pagesQualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector's Field GuideSukhdeep Kaur MaanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5: How Sociologists Do ResearchDocument7 pagesChapter 5: How Sociologists Do ResearchhoorNo ratings yet

- Case Study Research (1)Document5 pagesCase Study Research (1)Rao Abdul RafahNo ratings yet

- QualmethodsDocument13 pagesQualmethodsapi-298092263No ratings yet

- Research Assignment of Research Methods and Legal WritingDocument9 pagesResearch Assignment of Research Methods and Legal WritingSaiby KhanNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Quantitative ResearchDocument5 pagesCharacteristics of Quantitative ResearchMuveena ThurairajuNo ratings yet

- Case Study Research TechniquesDocument6 pagesCase Study Research TechniquesDivya PardalNo ratings yet

- Characteristics, Strengths and Weaknesses, Kinds, and Importance of Qualitative ResearchDocument6 pagesCharacteristics, Strengths and Weaknesses, Kinds, and Importance of Qualitative ResearchVincent AcapenNo ratings yet

- ParticipatoryDocument14 pagesParticipatorysaurabh887No ratings yet

- Interviews: In-Depth, Semistructured: GlossaryDocument6 pagesInterviews: In-Depth, Semistructured: GlossaryKristianaNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Case AnalysisDocument17 pagesCooperative Case AnalysisAkubuike EluwaNo ratings yet

- Research MethodsDocument8 pagesResearch MethodsNGOYA COURTNEYNo ratings yet

- Reseach ExamDocument18 pagesReseach ExamHungry HopeepigNo ratings yet

- Midterm Examination in Qualitative ResearchDocument8 pagesMidterm Examination in Qualitative ResearchJohnny JohnnyNo ratings yet

- Describes Characteristics, Strengths, Weaknesses, and Importance of Qualitative ResearchDocument7 pagesDescribes Characteristics, Strengths, Weaknesses, and Importance of Qualitative ResearchMa Alona Tan DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Chapter III - Methodology - Group IIDocument9 pagesChapter III - Methodology - Group IILindsay MedrianoNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet in Research 9Q1W2finalDocument6 pagesActivity Sheet in Research 9Q1W2finalAsh AbanillaNo ratings yet

- All Resumes of All Qualitative MaterialsDocument10 pagesAll Resumes of All Qualitative MaterialsSH TMNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 PDFDocument6 pagesPractical Research 1 PDFLove Qu CherrybelNo ratings yet

- MethodologyDocument7 pagesMethodologyGrace T KalifNo ratings yet

- The Case Study As A Research MethodDocument16 pagesThe Case Study As A Research MethodAshrul Anwar MukhashenNo ratings yet

- Research CaseDocument9 pagesResearch CaseDavidNo ratings yet

- Group 2 Qualitative StudyDocument18 pagesGroup 2 Qualitative StudyKyla RoceroNo ratings yet

- Research Methods: Simple, Short, And Straightforward Way Of Learning Methods Of ResearchFrom EverandResearch Methods: Simple, Short, And Straightforward Way Of Learning Methods Of ResearchRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Choosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesFrom EverandChoosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesNo ratings yet

- Data Warehousing, Mining, Neural NetworkDocument26 pagesData Warehousing, Mining, Neural NetworkRema VanchhawngNo ratings yet

- Eleven Multivariate Analysis TechniquesDocument4 pagesEleven Multivariate Analysis TechniquesHarit YadavNo ratings yet

- Factor Analysis Is An Interdependence Technique Whose Primary Purpose Is To Define The UnderlyingDocument3 pagesFactor Analysis Is An Interdependence Technique Whose Primary Purpose Is To Define The UnderlyingRema VanchhawngNo ratings yet

- Nature and Assumptions of Qualitative ResearchDocument24 pagesNature and Assumptions of Qualitative ResearchRema VanchhawngNo ratings yet

- Data Warehousing, Mining, Neural NetworkDocument7 pagesData Warehousing, Mining, Neural NetworkRema VanchhawngNo ratings yet

- Man Leh MualDocument3 pagesMan Leh MualRema VanchhawngNo ratings yet

- Substance Use DisorderDocument3 pagesSubstance Use DisorderRema VanchhawngNo ratings yet

- Objective QuestionsDocument19 pagesObjective QuestionsDeepak SharmaNo ratings yet

- 199-Article Text-434-1-10-20200626Document11 pages199-Article Text-434-1-10-20200626ryan renaldiNo ratings yet

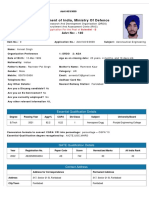

- DrdoDocument2 pagesDrdoAvneet SinghNo ratings yet

- The Ethological Study of Glossifungites Ichnofacies in The Modern & Miocene Mahakam Delta, IndonesiaDocument4 pagesThe Ethological Study of Glossifungites Ichnofacies in The Modern & Miocene Mahakam Delta, IndonesiaEry Arifullah100% (1)

- Understanding Power Dynamics and Developing Political ExpertiseDocument29 pagesUnderstanding Power Dynamics and Developing Political Expertisealessiacon100% (1)

- Unit 5 - Assessment of One'S Teaching Practice: Universidad de ManilaDocument15 pagesUnit 5 - Assessment of One'S Teaching Practice: Universidad de ManilaDoc Joey100% (3)

- Internal Controls and Risk Management: Learning ObjectivesDocument24 pagesInternal Controls and Risk Management: Learning ObjectivesRamil SagubanNo ratings yet

- ST326 - Irdap2021Document5 pagesST326 - Irdap2021NgaNovaNo ratings yet

- ECE Laws and Ethics NotesDocument29 pagesECE Laws and Ethics Notesmars100% (1)

- Drag Embedded AnchorsDocument6 pagesDrag Embedded AnchorsrussellboxhallNo ratings yet

- GCSE H3 02g4 02 3D TrigonometryDocument2 pagesGCSE H3 02g4 02 3D TrigonometryAndrei StanescuNo ratings yet

- 6 Main Rotor Config DesignDocument44 pages6 Main Rotor Config DesignDeepak Paul TirkeyNo ratings yet

- 31 Legacy of Ancient Greece (Contributions)Document10 pages31 Legacy of Ancient Greece (Contributions)LyreNo ratings yet

- Running Head:: Describe The Uses of Waiting Line AnalysesDocument6 pagesRunning Head:: Describe The Uses of Waiting Line AnalysesHenry AnubiNo ratings yet

- 123 The Roots of International Law and The Teachings of Francisco de Vitoria As A FounDocument23 pages123 The Roots of International Law and The Teachings of Francisco de Vitoria As A FounAki LacanlalayNo ratings yet

- Ninja's Guide To OnenoteDocument13 pagesNinja's Guide To Onenotesunil100% (1)

- HRM Assignment Final - Case StudyDocument7 pagesHRM Assignment Final - Case StudyPulkit_Bansal_2818100% (3)

- QUIZ 2 BUMA 20013 - Operations Management TQMDocument5 pagesQUIZ 2 BUMA 20013 - Operations Management TQMSlap ShareNo ratings yet

- Symbiosis Skills and Professional UniversityDocument3 pagesSymbiosis Skills and Professional UniversityAakash TiwariNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1747938X21000142 MainDocument33 pages1 s2.0 S1747938X21000142 MainAzmil XinanNo ratings yet

- J05720020120134026Functions and GraphsDocument14 pagesJ05720020120134026Functions and GraphsmuglersaurusNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Sim MechanicsDocument840 pagesTutorial Sim MechanicsHernan Gonzalez100% (4)

- READING 4.1 - Language and The Perception of Space, Motion, and TimeDocument10 pagesREADING 4.1 - Language and The Perception of Space, Motion, and TimeBan MaiNo ratings yet

- The Importance of WritingDocument4 pagesThe Importance of WritingBogdan VasileNo ratings yet

- 1993 - Kelvin-Helmholtz Stability Criteria For Stratfied Flow - Viscous Versus Non-Viscous (Inviscid) Approaches PDFDocument11 pages1993 - Kelvin-Helmholtz Stability Criteria For Stratfied Flow - Viscous Versus Non-Viscous (Inviscid) Approaches PDFBonnie JamesNo ratings yet

- Detect Plant Diseases Using Image ProcessingDocument11 pagesDetect Plant Diseases Using Image Processingvinayak100% (1)

- Scan & Pay Jio BillDocument22 pagesScan & Pay Jio BillsumeetNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Waste-Water Treatment Using Activated Carbon and Fullers Earth - A Case StudyDocument6 pagesComparison of Waste-Water Treatment Using Activated Carbon and Fullers Earth - A Case StudyDEVESH SINGH100% (1)

- Feasibility of Traditional Milk DeliveryDocument21 pagesFeasibility of Traditional Milk DeliverySumit TomarNo ratings yet