Professional Documents

Culture Documents

While Walcott Dedicated Much of The 1960s To Developing The Trinidad Theatre Workshop and To Rewriting Earlier Dramas

Uploaded by

Tanishq MalhotraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

While Walcott Dedicated Much of The 1960s To Developing The Trinidad Theatre Workshop and To Rewriting Earlier Dramas

Uploaded by

Tanishq MalhotraCopyright:

Available Formats

While Walcott dedicated much of the 1960s to developing the Trinidad

Theatre Workshop and to rewriting earlier dramas, his primary focus was

on poetry. Between 1964 and 1973 he published four volumes which

continued his exploration and expansion of traditional forms and which

increasingly concerned themselves with the position of the poet in the

postcolonial world. In contrast to the plays of this period which arise from

a sense of shared colonial history and local mythology, The Castaway and

Other Poems (1964) draws on the figure of Robinson Crusoe to suggest

the isolation of the artist. “As a West Indian,” Katie Jones suggests, “the

poet can be seen as a castaway from both his ancestral cultures, African

and European, stemming from both, belonging to neither. To salve this

split, Walcott creates a castaway who is also a new Adam . . . whose task

is to name his world. Walcott’s castaway is a poet who creates and gives

meaning to nothingness”. Coping with internal division remains a concern

in The Gulf, which calls on the body of water separating St. Lucia from the

United State as a metaphor for the breach between the poet and all he

loves, between his adult consciousness and childhood memories, his

international interests and the feeling of community in his homeland.

Walcott explores these themes again in Another Life, a book-length

autobiographical poem that examines the important roles of poetry,

memory, and historical consciousness in bridging the distances within the

postcolonial psyche.

This investigation transferred to his dramatic writings in the 1970s,

which address the problems of Caribbean identity against the

backdrop of political and racial strife and which increasingly find

solutions to these troubles in the individual. These works also display

an expansion of his artistic concerns into different genres. After a

comical turn in Jourmard, Walcott wrote two musicals in collaboration

with Galt MacDermont: The Joker of Seville (1974), a patois adaptation

of Molina’s El buladorde Sevella, and O Babylon! (1976), a portrayal of

Rastafarians in Jamaica at the time of Haile Selassie’s 1966 visit and

which uses reggae music as a means of exploring West Indian

identity. O Babylon! also marked the end of Walcott’s association with

the Trinidad Theatre Workshop and the beginning of new period of

dramatic writing, highlighted by plays such as Remembrance (1977)

and Pantomime (1978). The protagonist of Remembrance, Albert Perez

Jordan, is a schoolmaster who lost his oldest son in the 1970 Black

Power uprising and who remains distressed by a political commitment

he cannot understand. Unable to connect with his family or with his

own past, Jordan finds himself divided between an older generation

committed to tradition and a younger one playing at revolution.

Characters in the comedic Pantomine confront similar divisions, but

here the issue of race comes to the fore. Reviving the Crusoe story

once again, Walcott creates a play-within-a-play and recasts the roles

so that Jackson, a black hotel servant, plays Crusoe and his white

employer plays Friday. This reversal highlights the fraught

relationship that binds black to white, master to slave, and colonizer

to colonized. Far from being an irreparable situation, however,

Jackson’s ability to synthesize his calypso talents with a poetic use of

the English language suggests a respect for differences and a

possibility for healing old wounds.

You might also like

- Hybridity and WalcottDocument7 pagesHybridity and WalcottTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Derek Walcott EssayDocument4 pagesDerek Walcott EssayStephen Pommells100% (2)

- Modern Poetry and W.B.yeats - An OverviewDocument14 pagesModern Poetry and W.B.yeats - An OverviewDr.Indranil Sarkar M.A D.Litt.(Hon.)100% (1)

- William Butler YeatsDocument4 pagesWilliam Butler YeatsDan Gya Lipovan100% (1)

- African-American Literature and Other Minorities: Olaudah Equiano (1789) - in The 19Document5 pagesAfrican-American Literature and Other Minorities: Olaudah Equiano (1789) - in The 19hashemdoaaNo ratings yet

- Jose Garcia VillaDocument29 pagesJose Garcia VillaLuigi MendozaNo ratings yet

- The Modernist RevolutionDocument2 pagesThe Modernist RevolutionAntonia AntoNo ratings yet

- Neruda The Way Spain WasDocument8 pagesNeruda The Way Spain WasHardik Motsara0% (1)

- Biography WalcottDocument3 pagesBiography Walcottalanoud obeidatNo ratings yet

- Adela ZamudioDocument6 pagesAdela ZamudioAlan AguirreNo ratings yet

- Modern Poetry and W B Yeats An Overview PDFDocument14 pagesModern Poetry and W B Yeats An Overview PDFVICKYNo ratings yet

- Alfredo Espin1Document10 pagesAlfredo Espin1Ciber Genesis Rosario de MoraNo ratings yet

- Zavala Becoming Modern 5Document43 pagesZavala Becoming Modern 5eksiegel100% (1)

- Ingles Salazar BondyDocument13 pagesIngles Salazar BondyJaime Viveros PanihuaraNo ratings yet

- Mexican Poetry After The AvantgardeDocument14 pagesMexican Poetry After The AvantgardeEliana HernándezNo ratings yet

- Virginia Woolf:: Marguerite YourcenarDocument3 pagesVirginia Woolf:: Marguerite YourcenarveronicaNo ratings yet

- Modern Poetry - Tse, Wby, DTDocument6 pagesModern Poetry - Tse, Wby, DTAkashleena SarkarNo ratings yet

- Twentieth CenturyDocument46 pagesTwentieth CenturySayeed AbdulhiNo ratings yet

- SaimaDocument14 pagesSaimapanefi7316No ratings yet

- SaimaDocument8 pagesSaimapanefi7316No ratings yet

- Ernesto Cardenal EssayDocument42 pagesErnesto Cardenal EssayALAB UPNo ratings yet

- BlankDocument8 pagesBlanknoirNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document46 pagesChapter 3eloisa marie acieloNo ratings yet

- The Night. Both Novels Hew Closely To The Realist Tradition. Lazaro Francisco, The EminentDocument4 pagesThe Night. Both Novels Hew Closely To The Realist Tradition. Lazaro Francisco, The Eminentaruxx linsNo ratings yet

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)Document5 pagesSamuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)Muhammad Maad RazaNo ratings yet

- Modernist Poetry Lectures-1Document7 pagesModernist Poetry Lectures-1aminaimo33No ratings yet

- Philippine Literature in The Contemporary PeriodDocument3 pagesPhilippine Literature in The Contemporary PeriodDanna Mae Terse YuzonNo ratings yet

- (English) Eterno Feminino 1976 Rosario CastellanosDocument18 pages(English) Eterno Feminino 1976 Rosario CastellanosWENXIN LIANGNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature in The PostDocument3 pagesPhilippine Literature in The PostLou CsonNo ratings yet

- Pillar of Salt: An Autobiography, with 19 Erotic SonnetsFrom EverandPillar of Salt: An Autobiography, with 19 Erotic SonnetsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- 20TH Century LiteratureDocument7 pages20TH Century LiteratureAna Maria RaduNo ratings yet

- Dylan and Picasso: Masterminds of Their TimesDocument7 pagesDylan and Picasso: Masterminds of Their TimesJacqueline Tawney100% (1)

- Biografías en Ingles y Español de Escritores SalvadoreñosDocument6 pagesBiografías en Ingles y Español de Escritores SalvadoreñosNaun RyukNo ratings yet

- The First Half of The 20Th Century Poetrty: Georgian PoetryDocument13 pagesThe First Half of The 20Th Century Poetrty: Georgian PoetryGiorgia SalemiNo ratings yet

- Erek Walcott, Poeta, Dramaturgo e Ensaísta, Nasceu em 1930, em CastriesDocument4 pagesErek Walcott, Poeta, Dramaturgo e Ensaísta, Nasceu em 1930, em CastriesJuliana GomesNo ratings yet

- Unit-44The Eater Poetry of W.B. YeatDocument12 pagesUnit-44The Eater Poetry of W.B. YeatLima CvrNo ratings yet

- Name Beenish Siraj Semster BS Bridging Teacher Shehzad Ahmad Sheikh Assignment Romantic Age Submission Date 15/04/2021Document2 pagesName Beenish Siraj Semster BS Bridging Teacher Shehzad Ahmad Sheikh Assignment Romantic Age Submission Date 15/04/2021Beenish sirajNo ratings yet

- T.S. Eliot: BiographyDocument10 pagesT.S. Eliot: BiographyHudda FayyazNo ratings yet

- FOUN1101 Assignment 2 KamitaPreddie BSC NursingDocument9 pagesFOUN1101 Assignment 2 KamitaPreddie BSC Nursingkamita preddieNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 PDFDocument16 pagesUnit 2 PDFSambuddha GhoshNo ratings yet

- Appreciating Amado VDocument11 pagesAppreciating Amado VFrancis del RosarioNo ratings yet

- HSC Task 3 Draft 3Document3 pagesHSC Task 3 Draft 3Frances LechnerNo ratings yet

- Robert Lowell: "Skunk Hour" by Troy Jollimore - PDocument6 pagesRobert Lowell: "Skunk Hour" by Troy Jollimore - PjerrymonacoNo ratings yet

- New York School and The Black Arts MovementDocument7 pagesNew York School and The Black Arts Movementxiton weaNo ratings yet

- Literature - The Romantic AgeDocument14 pagesLiterature - The Romantic AgeLiana Esa FajrianNo ratings yet

- 07 Chapter 2Document147 pages07 Chapter 2PinkyFarooqiBarfi100% (1)

- Post Modernism and Feminism in The Select Poems Sylvia PlathDocument13 pagesPost Modernism and Feminism in The Select Poems Sylvia PlathBiljana BanjacNo ratings yet

- Gender in Modernism: Virginia Woolf's OrlandoDocument7 pagesGender in Modernism: Virginia Woolf's OrlandoYanina Leiva100% (1)

- T. S. Eliot'S Modernism in Thewaste Land: Asha F. SolomonDocument4 pagesT. S. Eliot'S Modernism in Thewaste Land: Asha F. SolomonAmm ÃrNo ratings yet

- T.S. EliotDocument3 pagesT.S. EliotMihaela Beatrice ConstantinescuNo ratings yet

- CASTEDocument4 pagesCASTEN PNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature in The Post-War and Contemporary PeriodDocument4 pagesPhilippine Literature in The Post-War and Contemporary PeriodDherick RaleighNo ratings yet

- Mahananda A Far Cry From AfricaDocument29 pagesMahananda A Far Cry From Africawxy002No ratings yet

- Evans On Storni FINAL Revised by BP 2 June PDFDocument20 pagesEvans On Storni FINAL Revised by BP 2 June PDF,,,,No ratings yet

- The Road Not Taken Is A Poem Written by Robert Frost in 1916. It Talks About The Theme of Choices and The Consequences They Entail. First, The Speaker Reflects His Contemplation Over Two DivergingDocument2 pagesThe Road Not Taken Is A Poem Written by Robert Frost in 1916. It Talks About The Theme of Choices and The Consequences They Entail. First, The Speaker Reflects His Contemplation Over Two DivergingThe 3d PlanetNo ratings yet

- About Arthur MillerDocument21 pagesAbout Arthur MillerAhmed AliNo ratings yet

- YT Live Brief KeerthiDocument1 pageYT Live Brief KeerthiTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Women in Gandhian Movement - I PDFDocument74 pagesWomen in Gandhian Movement - I PDFTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- YT Live Brief KeerthiDocument1 pageYT Live Brief KeerthiTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- HYBRIDITY AND WALCOTT Final PDFDocument8 pagesHYBRIDITY AND WALCOTT Final PDFTanishq Malhotra50% (2)

- Civil Disobediance Role of WomenDocument60 pagesCivil Disobediance Role of WomenTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Feminist Movements in IndiaDocument14 pagesFeminist Movements in IndiaTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- FractionandFusion PaperDocument12 pagesFractionandFusion PaperTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Annhad ProposalDocument14 pagesAnnhad ProposalTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Symfiesta Brochure Final - CompressedDocument21 pagesSymfiesta Brochure Final - CompressedTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Ribentrop Molotov PactDocument5 pagesRibentrop Molotov PactNicolae_BeldimanNo ratings yet

- 05 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument18 pages05 - Chapter 1 PDFTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- War Communism and NEPDocument8 pagesWar Communism and NEPTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Family and Gender in The Industrial RevolutionDocument11 pagesFamily and Gender in The Industrial RevolutionTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Rise of The MarathasDocument17 pagesRise of The MarathasTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Revi BA HDocument114 pagesRevi BA HHabib ManzerNo ratings yet

- The WarlordsDocument24 pagesThe WarlordsTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Social and Ideological Factors Behind 1848 RevolutionsDocument5 pagesSocial and Ideological Factors Behind 1848 RevolutionsTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Ali Qureshi and Hasan Raza: NamesDocument16 pagesMuhammad Ali Qureshi and Hasan Raza: NamesTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Canton Trade SystemDocument14 pagesCanton Trade SystemTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Lesson 15 - The Impact of War CommunismDocument10 pagesLesson 15 - The Impact of War CommunismTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- The Russian Revolution PDFDocument15 pagesThe Russian Revolution PDFTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Period of War CommunismDocument4 pagesPeriod of War CommunismTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- History (6 1 5)Document30 pagesHistory (6 1 5)Tanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- History: Subhas Ranjan Chakraborty, Asstt. Prof. (RTD.), Presidency College, KolkataDocument31 pagesHistory: Subhas Ranjan Chakraborty, Asstt. Prof. (RTD.), Presidency College, KolkataTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Bourbon The Rise Fall and Rebirth of An American Whiskey Fred MinnickDocument328 pagesBourbon The Rise Fall and Rebirth of An American Whiskey Fred Minnick孙艺博100% (1)

- Character Study OperaDocument2 pagesCharacter Study Operaapi-254073933No ratings yet

- The Judge's HouseDocument31 pagesThe Judge's HousekuroinachtNo ratings yet

- Danny Jones Pool ScheduleDocument1 pageDanny Jones Pool ScheduleCharlestonCityPaperNo ratings yet

- 100 Must-Read Fantasy Novels PDFDocument208 pages100 Must-Read Fantasy Novels PDFJoel100% (1)

- The One Ring - Loremasters Screen PDFDocument5 pagesThe One Ring - Loremasters Screen PDFtcnbagginsNo ratings yet

- Anastasia Vassiliou. Argos From The Ninth To Fifteenth Centuries PDFDocument28 pagesAnastasia Vassiliou. Argos From The Ninth To Fifteenth Centuries PDFMauraAlbinaNo ratings yet

- What Is Memory Studies?Document9 pagesWhat Is Memory Studies?Will KurlinkusNo ratings yet

- PoetryDocument4 pagesPoetryAreebaNo ratings yet

- Dzexams 3am Anglais d1 20180 1052824Document2 pagesDzexams 3am Anglais d1 20180 1052824fatihaNo ratings yet

- T.V. & Video ConnectorsDocument7 pagesT.V. & Video ConnectorsEldie TappaNo ratings yet

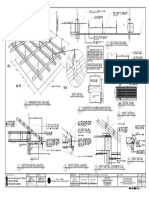

- 7 Section (Ceiling) : Architectural Design Position: Architect PRC No.: 0018676 PTR No.: 8941423 TIN No.: 907-359-364Document1 page7 Section (Ceiling) : Architectural Design Position: Architect PRC No.: 0018676 PTR No.: 8941423 TIN No.: 907-359-364John Bryan AguileraNo ratings yet

- Greek NameDocument10 pagesGreek Namecermjh21No ratings yet

- De Lauretis, Teresa. Guerrilla in The Midst. Women's CinemaDocument20 pagesDe Lauretis, Teresa. Guerrilla in The Midst. Women's CinemaKateryna SorokaNo ratings yet

- 898 Product Tech Data SheetDocument1 page898 Product Tech Data SheetPowerGuardSealersNo ratings yet

- Umbrella Run Defense ConceptDocument7 pagesUmbrella Run Defense ConceptabilodeauNo ratings yet

- Brick Bonds v2 PDFDocument5 pagesBrick Bonds v2 PDFGADDABATHINA SURESHNo ratings yet

- Handicraft Periodical TestDocument3 pagesHandicraft Periodical TestKristine JarabeloNo ratings yet

- Eschatology - Gog and Magog - Ezekiel 38-39 (Moscala)Document35 pagesEschatology - Gog and Magog - Ezekiel 38-39 (Moscala)Rudika Puskas100% (1)

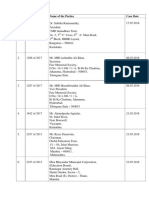

- S.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDDocument4 pagesS.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDAasim Ahmed ShaikhNo ratings yet

- 20 Windows Keyboard Shortcuts You Might Not KnowDocument4 pages20 Windows Keyboard Shortcuts You Might Not KnowjackieNo ratings yet

- The Three Important Facts Which Influence The Literature of Victorian AgeDocument6 pagesThe Three Important Facts Which Influence The Literature of Victorian Agerisob khanNo ratings yet

- Contoh Format Final Paper (Technique)Document7 pagesContoh Format Final Paper (Technique)Nini Nurani RakhmatullahNo ratings yet

- Load SchedDocument1 pageLoad SchedNikko Catibog GutierrezNo ratings yet

- AQS-001 (F) Type A PDFDocument1 pageAQS-001 (F) Type A PDFbarabatina100% (1)

- DeskTop LAA6E84Document164 pagesDeskTop LAA6E84Muhammad AbubakarNo ratings yet

- Epic Poetry: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument19 pagesEpic Poetry: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediabharathrk85No ratings yet

- Charlescorrea 1Document83 pagesCharlescorrea 1Riya MehtaNo ratings yet

- Carl Krockel D.H. Lawrence and D.H. Lawrence and GermanyGermany - The Politics of Influence (Costerus NS 164) 2007Document344 pagesCarl Krockel D.H. Lawrence and D.H. Lawrence and GermanyGermany - The Politics of Influence (Costerus NS 164) 2007ana_maria_anna_6No ratings yet

- Vocabulary O Level - TEST 46-60Document15 pagesVocabulary O Level - TEST 46-60Giok ZaimaNo ratings yet