Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cross New Laboratory of Dreams PDF

Uploaded by

KaiserhuffOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cross New Laboratory of Dreams PDF

Uploaded by

KaiserhuffCopyright:

Available Formats

The New Laboratory of Dreams:

Role-playing Games as Resistance

Katherine Angel Cross

“The virtual world” can be said to encompass a great many things: the

Internet as a whole, specific spaces therein, the simulacra of media imag-

ery in general, or video gaming specifically. The emancipatory potential

of the whole enterprise has long arrested feminist theorists (Haraway

1990; Stone 1995; Turkle 1995), and some reflect on the history of femi-

nist interventions into the virtual as evincing a dichotomy between “uto-

pian” and “dystopian” thinking (Boyd 2001; Magnet 2007). However, I

would challenge the idea that the distinction is so clean. This dichoto-

mous abstraction obscures the complex perspective often sketched by

so-called dystopian cyberfeminist theorists. Lisa Nakamura (1995), for

instance, was an early theorist who suggested that there was a profound

continuity between the physical world and the virtual one. She showed,

with sobering ethnographic examples from the online roleplaying game

LambdaMOO, that the balance of power in the world seeped into the

World Wide Web; what disrupts the “dystopia” narrative, however, is that

this complex understanding of power was not intended to be pessimistic.

Toward the end of her paper, Nakamura offered her hope that the play-

ers themselves would push back against the boundaries being constructed

in the virtual world. Eagerly seizing on the rich stable of metaphors that

technology offered, Nakamura said each act of roleplay that countered the

“Orientalized theatricality” of racist/sexist play was a “bug” that would

“[jam] the ideology machine.”

What is roleplaying and how can it do this? Roleplaying is something

that instantiates what “utopian” cyberfeminists dreamed of: creating a

character of your own design that you then perform and embody in virtual

WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 40: 3 & 4 (Fall/Winter 2012) © 2012 by Katherine Angel Cross.

70 All rights reserved.

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 70 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 71

social space. But to understand its emancipatory potential, and the pos-

sibilities it raises as a “third way” between the false dichotomy of u/dys-

topia, we have to rediscover Hilary Rose’s Laboratory of Dreams—a vivid

workshop where feminist science fiction became enchanting feminist

theory. We must also survey pen-and-paper roleplaying games (an excel-

lent summary thereof can be found in Dormans 2006). Such games render

social construction richly visible through their heavy emphasis on charac-

ter, imagination, and story, which all work together as part of a process of

constant enactment and engagement; a perpetual process of ‘becoming.’

I will begin by elaborating on the history of the Laboratory of Dreams

concept and its roots in feminist science fiction, then move into a brief auto-

ethnographic discussion that illustrates a defiant becoming in the midst of

oppressive virtual space, finally moving into an analysis of the roleplaying

game (RPG) Eclipse Phase as something that builds on “becoming” and

institutionalizes it in a way many other RPGs simply do not. Like liter-

ary science fiction, roleplaying is always moving toward something new,

iterating through never ending phases that progress one’s character toward

an infinite horizon. The enchantingly creative art that inheres to creating a

new world and fully human characters within it fires the imagination anew

as regards this world. The warnings of earlier cyberfeminist theorists are

vital to keep in mind—the whole purpose of this essay is to combine an

emancipatory project with their nuanced understanding of the pitfalls and

continuity of power, not to fall into the trap of Utopia. But in the process

I hope to show how Nakamura’s “ghost in the machine” is rising in virtual

space and that instituting feminist roleplaying games as a new laboratory

of dreams can build on this hopeful trend.

The Laboratory of Dreams

In many ways, feminist science fiction is the historical antecedent to the

avowedly feminist roleplaying games I hope to see created. For feminist

scholar Hilary Rose, science fiction was an important issue to take on in

her book Love, Power, and Knowledge (1994) precisely because it spoke to

a passionate urgency and the need to imagine the world for which femi-

nists were fighting. Toward the end of her book, she situates feminist sci-

ence fiction as essential to transforming science-in-fact. In a chapter titled

“Dreaming the Future” she quickly lays out why something as seemingly

frivolous as the pulp genre of sci-fi, repurposed as a creator of “feminist

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 71 9/24/12 12:57 PM

72 Katherine Angel Cross

myth-making,” could have such great sociopolitical import: “Feminist sci-

ence fiction has created a privileged space—a sort of dream laboratory—

where feminisms may try out different wonderful and/or terrifying social

projects. In these vivid u/dystopias the reader is invited to play safely

and seriously with social possibilities that are otherwise excluded by the

immediacy of daily life, by the conventions of the dominant culture and by

fear” (Rose 1994, 228).

The great project of social justice has been the changing of the world,

ostensibly for the better. There is, percolating in the minds of many an

activist, a vision of the new world they would like to create, a world where

some idea of justice would prevail. For Rose and other proponents of the

“laboratory” thesis, science fiction creates a space where we can dream

these ideas and in some ways even try them out (Merrick 1998, 2009).

Donna Haraway put the matter succinctly when she said that “the best SF

. . . redid what counts as—what is—real” (2011, 6). I would not limit this

merely to visions of utopia or dystopia either, however. These genres allow

for a complex and thoughtful sketching out of social dynamics that stub-

bornly refuse to fall on either side of that dichotomy—in this way, very

much like our own world.

Activism is always grounded in a challenging present that demands

immediate, short-term solutions merely to get us all to the next day of

resistance; what can be lost in that struggle for scraps of earth is a vision of

a better world. Rose argues that “more thinkable and sustainable futures

are nurtured by these dreams and myths of other wor(l)ds; and feminists,

whether working inside or outside the laboratories, have need of the labo-

ratory of dreams” (1994, 229).

Confronting a grotesque reality, paradoxically, necessitates a robust

charge into the realm of fantasy. In order to be what we see, we must

first create those visions and archetypes—fantasy is an ideal place to do

this. Imagination is not just a prerequisite of praxis here: it is praxis itself.

Dreaming, far from being inimical to and opposite of action, is folded back

into the urgent doing of political activism and restored to a position of

prominence and respect.

In the landmark anthology Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New

Perspectives on Gender and Gaming, the authors say in their preface that

“gaming activities are not neutral or isolated acts, but involve a person’s

becoming and acting in the world as part of the construction of a complex

identity” (Sun et al. 2008, xx). Gaming, and roleplaying in particular, is an

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 72 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 73

act of constant “becoming” that allows for self-conscious (or at least semi-

conscious) social reconstruction. Feminist transformation—the constitu-

tion of new gendered possibilities and new arrangements of power—can

be and often is one of those things.

Interactive Becoming

Recent research into how people interact with games—giving more heft

to just what the concept of “interactivity” can mean—demonstrates how

these possibilities may exist in the real world. Caroline Pelletier’s 2008

“Gaming in Context” examines the phenomenon of gender identity con-

struction through gameplay by speaking with young children in British

primary schools and having them make video games using a prearranged

set of tools that are easy to use but admit a good deal of customization.

She found that both boys and girls used their game designs to constitute a

gender identity in the real world that did not always line up with their per-

sonal interests in gaming. This arose from the complex ways the students

engaged with gender norms:

The reason their games re-enact game-based gender norms is that it

is precisely in relation to such norms (either for or against them) that

games are intelligible. However, norms are never simply maintained

but always remade—or made anew—in new games and new situations.

So making a game means designing in conventional ways in order to

be understood, but also appropriating such conventions and adapting

them to one’s particular situation—and therefore, in effect, changing

such conventions (Pelletier 2008, 156).

She uses this framing to emphasize the dialectical processes that char-

acterize identity formation. “Norms,” she says, “are therefore not simply

imposed on people but used actively to construct identity” (157), echoing

Barrie Thorne’s conception of “play” in her study of children around the

same age. For Thorne (1993), “play” is an active engagement with the sig-

nifiers that suffuse childhood and constitute proactive self-construction

in a way mediated but not obviated by power. Pelletier, in recognizing

the agency such construction may afford, argues that allowing youth to

design their own games gives them more power to use the norms that sur-

round them, rearrange them, transcend them, and potentially create some-

thing new.

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 73 9/24/12 12:57 PM

74 Katherine Angel Cross

Elizabeth Hayes made somewhat similar observations in her 2007

analysis of how two women made the most of Elder Scrolls: Morrowind,

a roleplaying video game set in a fairly open world where identity and

goals were more self-directed than in other titles. “Gendered Identities

at Play” detailed an ethnography of these two women and Hayes situated

this analysis in an idea that blurred the distinction between self and other:

“An intersection between the player’s real life identities and the identity of

the virtual character can be the source of new ways of viewing the world

and the self, at least in theory” (Hayes 2007, 27–28). Each woman felt the

constraints of societal sexism, but seemed to only begin from those lim-

its. Over the course of their adventure in Morrowind they began a process

of change, becoming something that combined dimensions of their old

selves with new, experimental pursuits. There is an arc that can be found

between their selves and the others they ended up pursuing and becom-

ing, similar to how this process works in roleplaying more generally.

All these people find ways of using the limited tools they are given and

using them in ways that were not intended by the developers and writers of

a given game. This transcendence occurs through not only through enact-

ing the role of the Other, but also through finding (constructing) yourself.

This double helix of growth, a beautiful dialectic of becoming, first made

itself known to me through personal experience.

Roleplaying as Transition

Despite World of Warcraft’s occasionally intense prejudice, locker room

environment, and antiqueer public atmosphere, it was where I discovered

myself as a woman through gameplay that offered me a social experience

that real life had denied me. This online roleplaying game, a fantasy world

of Elves and Orcs inhabited by millions of players, was the staging area

for a virtual experience that, in retrospect, was my bridge to a new under-

standing of myself. To be quite sure, this was not a possibility that was

bullet-pointed as a selling point on the back of World of Warcraft’s packag-

ing. “Uncover your transgender identity!” is scarcely marketed as a feature

of online games of any stripe; yet it happened. I was not alone in this. After

my coming out and identifying myself as a transsexual woman with a par-

ticular history, other trans people would tell me that they had also done a

good deal of “exploring” on the Internet, particularly through roleplaying

games that gave them the opportunity to play as the gender of their choice.

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 74 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 75

Roleplaying offered people a means of safely and comprehensively explor-

ing a subjectivity from which they were otherwise restricted.

Gaming, in this profound sense, becomes an expression of historian

Susan Stryker’s vision of trans-formation: “As we rise up from the operat-

ing tables of our rebirth, we transsexuals are something more, and something

other, than the creatures our makers intended us to be” (Stryker 2006b, 248;

emphasis mine). With characteristically stirring prose Stryker contests

the idea that transgender surgeries are somehow innately reinforcing of

a patriarchal gender order. She reminds us that people do something with

what is imposed upon them or given to them. Surgeons and psychiatrists,

she says, may have a certain end in mind when they allow trans people

access to hormone replacement therapy or surgery, but we are not nec-

essarily shackled to that vision. We can transcend their edicts and their

intentions. Similarly, Blizzard Entertainment’s envisaged ends in creating

World of Warcraft did not entail a transgender revolution or conceive even

of a transgender becoming. Yet I am here.

Sociologist Raewyn Connell observes that gender is very much a pro-

cess, “a structure of social practice.” She sees gender as both reacting to

and initiating social changes in perpetual dialectical interaction, forever

in motion much as it was during my time in World of Warcraft (Connell

1987; 2000, 71–76). It would, thus, be too simple to say that I was trying

to become something else or be something I was not. I was becoming.

Ontology bled into epistemology here and revealed to me the contingency

of my gendered situation. What was once passive certitude in the inflex-

ibility of my gender was revealed as a flexible point of view (gender-as-

epistemology), largely thanks to roleplaying.

Self and other dissolved, and I became aware of a process of becoming in

my gendered life, a horizon that I might never reach but one worth pursu-

ing. It was this cascade of realizations that led me to draw strength from my

fictional characters in World of Warcraft and Neverwinter Nights and realize

that what was true in the virtual world may be true in the physical one. It

allowed me to direct my own process of becoming and continuity between

myself and my roleplayed characters became apparent. Just as in the game,

I first began from what I knew; it then metamorphosed into something

beyond that and finally fed back into me.

In this lies the essence of resistance: the permanent recognition of

social contingency, of one’s agency in the midst of oppression’s crucible,

and the ability to find one’s self enchanted with the possibilities that can

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 75 9/24/12 12:57 PM

76 Katherine Angel Cross

spread before one. In seizing on the preceding one feels compelled to

recognize one’s motion and perhaps move faster. Seeing the future and

allowing yourself to be enchanted by the fantasy is what facilitates this

so well. What sets Eclipse Phase apart from many of its contemporaries is

that unlike many games, it consciously seizes on this, so much so that it

becomes especially good for transformative thinking.

“As if ‘Biological’ Means a Damn Thing Anymore”:

Eclipse Phase and Theory from an RPG Sourcebook

In her analysis of gendered play in Morrowind, Hayes discussed that game’s

limitations and speculated that “one of the most powerful ways that games

might be used to explore new ways of doing gender is by challenging some

fundamental assumptions about the nature of identity itself ” (2007, 45).

Enter Eclipse Phase. The game—originally conceived by Rob Boyle and

Brian Cross—arrests you with possibilities for change from the start. Its

tagline is “Your mind is software. Program it. Your body is a shell. Change

it. Death is a disease. Cure it. Extinction is approaching. Fight it” (Posthu-

man Studios 2012). To turn an old metaphor, in Eclipse Phase changing

identities is a feature, not a bug.

At the end of her paper Hayes noted that it was difficult to find “games

that offer players the opportunity to move in and out of different identities

or that reward atypical combinations of attributes and skills” (2007, 46).

Eclipse Phase is that game, one that may be fairly described as Nakamura’s

“ghost in the machine”—flawed, as any ghost might be, but still incredibly

interesting. My own gendered play in World of Warcraft was an act of semi-

conscious creative resistance within the terms of a game that was never

designed to accommodate it. Eclipse Phase, on the other hand, is built from

the very premise that calling the very nature of identity into question can

constitute a fun evening.

As is implied by the game’s slogan, changing one’s mind and body are

essential components of gameplay here. “My body, my choice” seems to

undergird gameplay here in a way few other games in any medium can

match. Where it qualifies this is not for the sake of enforcing any number

of norms regarding, say, gender, but rather for elaborate commentary on

class relations in the world of Eclipse Phase.

The RPG takes place in a future version of our own solar system, ten

years out from the Fall, a nuclear apocalypse on Earth sired by American

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 76 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 77

military hardware. Lush, culturally rich and advanced colonies exist else-

where in the system, however, and “transhumanity”—the human race as

augmented by now-routine bodily modification, literal cyborgs—lives

on. The rich campaign setting gives players a tremendous amount to think

about: gender and sex are extremely fluid, sexuality is normatively poly-

morphous, and the class politics of the game invite much critical reflec-

tion. The campaign sourcebook—the “rulebook” of any pen-and-paper

RPG—lends players a thorough education in the differences between

liberalism and radicalism, as well as multiple phases and wings of resis-

tance politics. Artwork adorns otherwise text-choked pages, bringing the

setting’s manifold distinctions to life in vivid renderings that immerse you

in this brave new solar system. Women of color abound as thinkers and

doers, not passive pornographic objects (see Fernández 1999; Nakamura

2000; Langer 2008, 97). They are also portrayed as being comfortable

with technology, using it with facility in a variety of ways. These images,

produced on a budget by an independent developer with a political mes-

sage—the promotion of transhumanism as well as a generally leftist class

and gender politics—are Nakamura’s “ghosts,” pushing back against hege-

monic images of women, particularly women of color.1 All this is part of

the default setting of a game routinely praised on RPG review websites as

being fun.2

Before going further it is worth exploring how this world will be laid

out and what the nature of its virtual space actually is. This is a pen-and-

paper roleplaying game; perhaps the most famous example of this genre/

medium is Dungeons & Dragons (Cook 2003). While such games share

many features with video games, it is an experience that becomes fully

visualized in one’s imagination rather than on a computer or television

screen. It is also one that is very likely to be shared in physical, rather than

virtual, company.

Another nontrivial distinction this creates is the fact that pen-and-

paper roleplaying games do not necessarily allow players to “hide” their

“true” selves from the people they interact with. If “no one knows you’re

a dog” on the Internet, everyone will around a roleplaying table. Pen-and-

paper roleplaying games are sourced from books that are used as guides for

gameplay that usually takes place between the participants seated around

a table (hence another name for the genre, “tabletop roleplaying”).3 The

impact of this requires more research and would bear directly on my the-

ory; the immediate presence of other, physical players could limit a per-

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 77 9/24/12 12:57 PM

78 Katherine Angel Cross

son’s freedom to play with things like identity in a challenging manner. But

as I will argue, Eclipse Phase’s value is that it heavily legitimizes precisely

the kind of transgressive play that could make trouble for a player of a dif-

ferent game.

Pen-and-paper roleplaying games also offer two layers of customiza-

tion that constitute a kind of proactive game design that occurs during

live play. For instance, players may find themselves acting as mediators

between two rival anarchist factions. The first layer of customization (that

of narrative) is built into the nature of the challenge: it can have several

outcomes based on the players’ actions. Do they succeed and help the col-

lectives reconcile? Merely set tempers flaring and initiate an altogether less

pleasant challenge? Start a whole new political movement? This evolving

and polymorphous story is worked out between the gamemaster and play-

ers, each playing his or her part in weaving/designing the narrative. The

story is made moment to moment. This free form overcomes the struc-

tural limitations of online RPGs like World of Warcraft, which often inhibit

roleplay (MacCallum-Stewart and Parsler 2008).

The second layer is made up of the statistics and dice rolls that help

mediate play.4 Most roleplaying games’ sourcebooks encourage players

to develop “house rules” and otherwise modify what they are given. To

return to my example, the sourcebook may dictate one set of rules for

handling diplomacy with dice rolls, but our gamemaster may elect to use

house rules unique to this story, or something more streamlined. 5 Or per-

haps our hypothetical gamemaster will do what I do: use a well-told story

in lieu of a successful dice roll. If I were the gamemaster setting this chal-

lenge, I would encourage my players to tell me a good story about their

negotiations, rather than simply roll dice to see whether or not they suc-

ceeded. This would be impossible in most video games, even multiplayer

ones. In the latter, players are pitted against an unchanging rule set carved

in digital marble; here rules flow as freely as story and are manipulated as

part of the player’s initiative. It is a social process.

What Pelletier’s research confirmed to her was that game development

is an act of power that could indeed change social relations; her goal is to

see “that game design can become an everyday domestic leisure activity”

(Pelletier 2008, 158). She did not see this occurring on a pure “transgres-

sive/oppressive” dyad, but instead saw it as a powerful means of engaging

with social norms and giving youth the power to begin modifying them.

I would add something more to this, however: pen-and-paper roleplay-

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 78 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 79

ing games are game design as an everyday domestic leisure activity. Eclipse

Phase, like most pen-and-paper games, recruits the players themselves in

changing the game to suit their tastes (creating “house rules,” for instance)

and to change the setting as they see fit to tell the stories they want to tell.

It excels in comparison with other pen-and-paper RPGs, however, in its

beginning this encouragement from a baseline that is already very politi-

cally charged and deeply thoughtful about its social space, one where vari-

able identity and gender-as-process are already built into the game prior

to player input.

Despite the malleability, sourcebooks exist for a reason. They pro-

vide an authoritative voice that allows players to start from a profession-

ally designed setting and rule set, sparing one the trouble of having to

start from a blank slate (for a useful discussion on the merits of rules in

games, see Nardi 2010, 76–80). This authoritative voice can encourage or

discourage certain kinds of play—even if players are free to ignore such

suggestions in theory. It is what makes Eclipse Phase’s “voice” all the more

noteworthy. The game writers use that power to articulate controversial

and politically charged ideas. Players are asked to consider “What does it

mean when you are born female but you are occupying a male body?” and

are informed about how the writers use gender pronouns: “When refer-

ring to specific characters, we use the gendered pronoun appropriate to

the character’s personal gender identity, no matter the sex of the morph

[body] they are in” (Snead et al. 2009, 114).

The last sentence situates the individual’s identity as the final arbiter of

his or her “true” gender, taking a page out of transgender rights discourse.

The authors also establish that the “singular they” will be the default pro-

noun used throughout the text, instead of the pseudogeneric pronouns of

“he/him.” The players, sitting around a table or at their computer screens,

become immersed in a world where the developers are telling them a new

story about gender. One even lacks the comfortable distance afforded

by the usual science fiction realms (“A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far

away . . .”). Eclipse Phase is set in our own neighborhood; the humans here

are not distant but are our own great-grandchildren. The setting makes

statements about gender and about inequality in terms that are starkly

familiar.

Consider another “authoritative” statement that the developers write

about their setting: “Gender has become an outdated social construct

with no basis in biology. After all, it’s hard to give credence to gender roles

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 79 9/24/12 12:57 PM

80 Katherine Angel Cross

when an ego can easily modify their sex, switch skins. . . . Many others

switch gender identities as soon as they reach adulthood or avidly pursue

repeated transgender switching. Still others examine and adopt untradi-

tional sex-gender identities such as neuters . . . or dual gender” (45). It

almost seems painfully obvious to say that the game has brought Donna

Haraway’s “cyborgs” to life vividly. This echoes Stryker’s formulation of

the sexed body: “‘Sex’ is a mash-up, a story we mix about how the body

means, which parts matter most, and how they register in our conscious-

ness or field of vision” (Stryker 2006a, 9).

Bodies are part of ever evolving identity here, both personal and

instrumental, always subject to change. You may choose a body designed

for zero gravity, for instance, or one that can fly in Venus’s atmosphere.

Haraway’s conception of a cyborg involved the rich social context that

Eclipse Phase provides, going beyond a mere grafting of technology onto a

human being (Haraway 2011, 6), while also ensuring a grounding in lived

reality that some feminists feared might be lost in virtual space (Magnet

2007, 585). Thus trans people are not only represented; the concept of

changing bodies/identities/genders is normalized well beyond anything

imaginable at present (and this is indeed the point: it makes the player

imagine it). In Eclipse Phase the name for the human race as a collective

had shifted to “transhumanity”; whether or not it was intended as a pun on

“transgender” is immaterial. It captures the varied meanings of “trans” all

in one: transsexual, transgender, transgressive, transcendent. Movement

and becoming.

It is worth remembering that Haraway’s storied cyborg was mes-

tizaje, who knew, lived, and thrived upon the multiple consciousnesses

that women of color inhabit (Haraway 1990, 218; Fernandez 1999, 62).

This conciencia de la mestiza (see Anzaldúa 1999) allowed her cyborg to

embody our complex and uneasy lives as feminists of color, and the lib-

erating potential therein. It may be too much to liken Eclipse Phase to the

work of Cherríe Moraga, say, but it nevertheless presents the player with

women in living color who travel between worlds of identity, speaking in

many tongues; it also shows them empowering themselves, inviting the

player to know such mestizaje women in a productive gaming space that is

precisely predicated on identity reformation in a politicized context. This

is a laboratory of dreams that we as women of color can easily see ourselves

in, a stark contrast to many video games where we instead find narratives

of resistance filtered through a much thicker haze of problematic racialized

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 80 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 81

portrayals (Langer 2008). We are too often uncounted, but Eclipse Phase

is that rarest of imaginative projects that encourages fruitful and creative

exploration of a complex, political identity as a woman of color.

This sort of volatility is a hallmark of the game. By even broaching the

possibility of “repeated sex/gender” switching the developers are positing

an especially radical formulation of the game’s base principle: that change

is a constant and all character in transhuman space is a highly conscious

and ongoing act of becoming. Further, it goes beyond the traditional M/F

dyad in choosing gender in a game, which, as Danah Boyd points out, is a

“slippage . . . between gender and sex—between the body and the perfor-

mance of identities. The question might be framed as one of gender, but

the answer is all about sex” (2001, 110). By contrast Eclipse Phase lets you

build your own gender and sex.

The website tells players that “the ability to switch your body at will,

from genetically-modified transhumans to synthetic robotic shells, opti-

mizing your character for specific missions” is a central part of the game,

and also touts the fact that “characters are skill-based, with no classes,

so players can customize their team roles and specialize in fields of their

choosing”—the latter is important to consider in light of Hayes’s arguing

that “not all choices were as functional as others” in Morrowind (Hayes

2007, 46). Through enabling truly free-form gameplay, Eclipse Phase

admits a wider variety of skill combinations that could be potentially effec-

tive, including—strikingly—academic skills.

The game promotes a profound reverence for social science (“astroso-

ciology” is a trainable skill in this game). In advising players on how to use

skills related to knowledge, like the aforementioned astrosociology, the

sourcebook suggests the following: “The real value of Knowledge skills

is in helping the characters—and the players—understand the world of

Eclipse Phase. In particular these skills can be used to . . . understand the

applicable science, socio-economic factors, or cultural or historical con-

text” (Snead et al. 2009, 185). Rare is the game that asks you to consider

socioeconomics, or anything like “cultural or historical context.” The

gameplay immerses players in critical thinking. A prerequisite of play is

having some means of navigating the complicated political world of the

post-Fall solar system.

Academic knowledge becomes a skill that can move mountains in a

given story line; journalists, social justice activists, researchers, deep space

drifter avant-garde artists now all become people with power in their own

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 81 9/24/12 12:57 PM

82 Katherine Angel Cross

right who can move the story along, in contrast to most games, which cen-

ter on combat experts. Multiple characters in the game are configured as

activists, from technosocialist Zora Moeller, who “feels a responsibility

to bring about the downfall of repressive capitalist structures” to various

activists for robotic rights and the rights of the animalian creatures known

as “uplifts.” Moeller and other activists mentioned in the game, such as Dr.

Katherine Santos, are women of color as well. The player is encouraged to

think in terms of not only a character’s ability to wound, but also his or her

ability to move in this world as a fully formed being. You as the player must

create a character that can act as an agent in a deeply troubled world that is

simultaneously rich in possibility, our own world through a dark looking

glass, but in “laboratory” form, free to be played with.

Pen-and-paper roleplaying games are an act of constant creation. It as

is if your character puts the world under her with each step she takes in

it; roleplaying is an act of imaginative constitution, making and remak-

ing. It is Connell’s structure of practice spelled out ludologically, Stryker’s

reclaimed Monster rising from the operating table, and Nakamura’s ghost

in the machine seizing its host. Eclipse Phase’s great distinction is that it

fully seizes on the process of becoming in order to both tell its own story

and entice players to consciously make their own in the same mold. A story

where identity is in flux, where technology’s social impact is highly vari-

able, where class, gender, and race are set center stage, and where one mili-

tates against powerful social forces in the crucible of trying times indeed

for the (trans)human race. What the authoritative voice of the sourcebook

does here is provide a rich and thriving society in which your character

confronts powerful social forces with her agency.

After all, this is a world where Cartesian dualism has folded back

against itself and collapsed into singularity. One’s consciousness is now a

downloadable and transmittable entity that can be “sleeved” into most any

body. Body-as-identity takes on a variety of meanings here; a body can be

like a beat-up used car one hopes to shed as soon as one can afford bet-

ter, or it can be a vital part of one’s identity, lovingly modified and altered

as an inextricable extension of one’s consciousness. Few other games—

video games or pen-and-paper games—encourage such. But beyond the

gendered possibilities here is the fact that this has become the material

foundation of class in this world: who has a biological body and who does

not. The “haves” specifically have biological bodies, while those who do

not either have low-grade bio bodies or mechanical ones. The latter, in par-

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 82 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 83

ticular, make up what the sourcebook refers to as “the clanking masses”—a

new underclass of human consciousnesses inhabiting mechanical bod-

ies made for menial and dangerous labor. Bodies matter, perhaps, more

than ever. What we see here are not ethereal Übermenschen homosocially

engaging in a contextless space, but full humans with bodies navigating a

deeply political world that is often as dirty and messy as it gets. The game

openly casts bodies as the contested terrain that they are in our own real

world and encourages players to think in those terms (Mohan et al. 2011).

The interesting things Eclipse Phase does are too numerous to explore

in one essay. Short stories that star femme genderqueer characters, artwork

featuring same-sex couples, a Latina doctor who acts as an early hero to

uplift rights activists, artwork that depicts women of color in positions of

strength sans objectification, a campaign setting where Asian people are

featured without Orientalist fetishization; Eclipse Phase compels its players

to cultivate a story in this world. Perhaps my favorite moment in the source-

books comes from a sidebarred short story when said doctor, Katherine

Santos, is proved right in the face of a male colleague who had just accused

her of having “lost [her] objectivity” (100). In the same story, a chimpan-

zee uplift speaks of this doctor as being his mother, noting that she is not

his “biological mother” before correcting himself by saying “as if the con-

cept of ‘biological’ means a damn thing anymore.” As well as being satisfy-

ing, this is one of several moments when the game developers throw the

notions of scientific objectivity and biological essentialism into question.

Conclusion

What makes pen-and-paper RPGs special is that they are a site of cre-

ation that necessarily expands the mind of the player. Fantasy is never a

far-off country that is forever foreign to even the peripheries of a person’s

consciousness; this is what makes it both dangerous and productive. The

roleplayed world is one that is constantly in the making. For both Pelle-

tier and myself, the “making” is essential to both the constitution of the

player’s identity and the remaking of social norms themselves. Eclipse

Phase’s fantasy has created a highly believable society, sparing no detail for

many of its moving (and breathing) parts. To extend the lab metaphor,

Eclipse Phase’s laboratory is fully stocked. Its laboratory is premised not on

techno-utopianism or apolitical optimism, but on the very critiques that

Nakamura raised in 1995: that technology had just as much power to rein-

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 83 9/24/12 12:57 PM

84 Katherine Angel Cross

scribe oppression as to liberate us from it. Eclipse Phase enjoins its players

to toy with both ideas: the dangers and virtues of fantasy. The beautifully

terrible power of dreaming.

Games like this, which enlist creative, political minds in its design, can

help to break the tide of prejudicial game design and writing. These are

tools that feminists can easily seize upon, using the well-worn pathways

that have been established by young feminists online and by other social

justice activists with a presence online who have created a ready-made net-

work for roleplaying to become the next stage of feminist storytelling. A

rich body of feminist academic literature also lays a number of theoretical

groundworks for such a project (Cassell and Jenkins 1998; Taylor 2006;

Corneliussen 2008). Feminist game designer Filamena Young used just

such strategies to create a pen-and-paper RPG aimed at children called

Flatpack: Fix the Future (Young 2012). It engages children as creative play-

ers in a postapocalyptic world that is hopeful. Rather than emphasizing

destruction, it stresses reconstruction and the agency of young people in

building a new and better world. Young’s work is in genealogical relation

with the feminist science fiction that has gone before; unlike SF, however,

the laboratory thus proffered is an open workshop that is constituted

through active, imaginative work. Every feminist, for instance, can now

become an Octavia Butler, Joanna Russ, or Ursula K. LeGuin.

Gaming in rich settings that represent a complex society like our own

has the potential to address the serious issues that scholars like Lisa Naka-

mura and Jodi O’Brien (1999) raised with regard to freedom in the virtual

realm. O’Brien’s great concern was that virtual space seemed to demand

recourse to the body, always bringing social relations back to binarist sexual

referents. But what if a roleplaying game subverted the dyad entirely from

the first page? My own autoethnographic evidence testifies to immense

possibility even in relatively restrictive video games, and thus the promise

of more politically insightful games like Eclipse Phase is that much greater.

There can be little doubt that no game is perfect, and feminist scholars may

find much to criticize in Eclipse Phase itself. But the game is best under-

stood as both a beginning and an incitement. Similarly, as Fernández,

Nakamura, and others have noted, there is immense danger in seeing “the

virtual” in purely emancipatory terms—this maneuver obscures the very

real ways that power works in the world. But it is my modest hope that

games like Eclipse Phase, politically astute as they are, can actualize the bet-

ter angels of the virtual world.

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 84 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 85

It is also my hope that this essay contributes in some small way to

the disruption of the utopia/dystopia dichotomy that pervades thinking

about imaginative fiction (Merrick 1998). Transcending this can produce

an even more stimulating and imaginative play space that simulates the

social turbulence of the real world. It works as well as it does because it

transcends old dichotomies while still being avowedly political. Although

not strictly a feminist RPG in provenance, it is a striking example of what

feminist RPGs might well offer. Science fiction gave fuller, imaginative

form to the utopian thinking of writers like Shulamith Firestone (1970),

who dreamed of technological solutions to women’s reproductive binds .

Pen-and-paper roleplaying games present us with another means of doing

so. In describing el camino de la mestiza (the mestiza way), Anzaldúa says

la mestiza “reinterprets history and, using new symbols, she shapes new

myths” (1999, 104). She may well have been describing roleplaying.

If roleplaying offers us the opportunity to be the characters we want to

see in popular media, and the opportunity to experiment with forgotten

futures and the utopias we dare not dream, then it behooves us all to enter

this laboratory of dreams and remake it.

Katherine Angel Cross is an undergraduate student and research assistant at Hunter Col-

lege, City University of New York, presently studying sociology and women and gender

studies. She is also coeditor of the feminist critical gaming blog The Border House.

Notes

1. Transhumanism, an international philosophical movement that has both

intrigued and troubled radical activists, is committed to “improving” the

human condition through the use of technology. An astute reader may well

note the potential political pitfalls of such a program, and they certainly have

not escaped transhumanism’s critics (for a stimulating example, see Midgley

2004; also Fernández 1999, 62). For the purposes of this essay, it is enough

to say that Eclipse Phase mostly steers clear of transhumanism’s more prob-

lematic dimensions, producing the politically engaged and complex roleplay-

ing game I am analyzing here.

2. For a good sampling of player reviews, see http://rpg.drivethrustuff.com/

product_reviews.php?products_id=64135. Notably, next to none castigate

this highly political title for being “too political.”

3. A pen-and-paper roleplaying game is one in which players discursively act

out the roles of characters in a fictional setting. These players are refereed

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 85 9/24/12 12:57 PM

86 Katherine Angel Cross

by a gamemaster (GM) who is responsible for guiding the direction of the

story according to the rule system laid out in the sourcebook. While the GM

is meant to be an arbiter who has the final say on rules and setting, and is the

“omniscient narrator” thereof, in practice the creation of the world is a col-

laborative process between both the GM and the players.

4. A small number of video games such as Morrowind and Neverwinter Nights

allow for extensive customization at both levels, but they are the exceptions

that both prove the rule and demonstrate the utility of roleplaying games in

any medium.

5. Skills, in the context of roleplaying games, are ways to mathematically model

proficiency in a certain activity. A skill is usually expressed as a number,

which is used by combining it with the result of a dice roll to try and rise

above a “challenge rating.” This allows a mixture of uncertainty (the dice)

and predictably rising success (the skill value) while allowing the difficulty

of the problem to vary (the challenge rating). Let us return to our example

of the anarchist kerfuffle. For the sake of simplicity, let us say the challenge

rating is 50 and a player has a diplomacy skill of 15. She may say something

like “I try to convince the syndicate leader to be more agreeable in these

talks” or (preferably) something with more flair like “I give an impassioned

speech about the need to respond to Collective X’s criticisms” and then pro-

ceed to act out the speech she has in mind. The player rolls a ten-sided die to

give her a multiple of ten; she rolls a 4—equivalent to 40. She adds this ran-

domly generated number to her diplomacy skill to get a total score of 55. She

thereby “wins” the check and “accomplishes” in the game what she said she

was trying to do. For more on how rules can positively structure a gameplay

experience, see Dormans 2006 and Nardi 2010.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1999. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San

Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Boyd, Danah. 2001. “Sexing the Internet: Reflections on the Role of

Identification in Online Communities.” In Feminist Frontiers. 9th ed., ed.

Verta Taylor, Nancy Whittier, and Leila Rupp, 108–15. New York: McGraw

Hill.

Cassell, Justine, and Henry Jenkins, eds. 1998. From Barbie to Mortal Kombat:

Gender and Computer Games. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of

Technology Press.

Connell, Raewyn. 1987. Gender and Power. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

———. 2000. Masculinities. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California

Press.

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 86 9/24/12 12:57 PM

The New Laboratory of Dreams 87

Cook, Monte. 2003. Dungeons & Dragons: The Dungeon Master’s Guide, Core

Rulebook II v 3.5. Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast.

Corneliussen, Hilde. 2008. “World of Warcraft as a Playground for Feminism.”

In Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of Warcraft Reader, ed. Hilde

G. Corneliussen and Jill W. Rettberg, 63–86. Cambridge: Massachusetts

Institute of Technology Press.

Dormans, Joris. 2006. “On the Role of the Die: A Brief Ludologic Study of Pen-

and-Paper Roleplaying Games and Their Rules.” Game Studies 6(1). http://

gamestudies.org/0601/articles/dormans.

Fernández, María. 1999. “Postcolonial Media Theory.” Art Journal 58(3):58–73.

Firestone, Shulamith. 1970. The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution.

New York: William Morrow.

Haraway, Donna. 1990. “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and

Socialist-Feminism in the 1980s.” In Feminism/Postmodernism, ed. Linda

Nicholson, 190–233. New York: Routledge.

———. 2011. “SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So

Far.” http://people.ucsc.edu/~haraway/Files/PilgrimAcceptanceHaraway.

pdf.

Hayes, Elizabeth. 2007. “Gendered Identities at Play: Case Studies of Two

Women Playing Morrowind.” Games and Culture 2(1):23–48.

Langer, Jessica. 2008. “The Familiar and the Foreign: Playing (Post)Colonialism

in World of Warcraft.” In Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of

Warcraft Reader, ed. Hilde G. Corneliussen and Jill W. Rettberg, 87–108.

Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

MacCallum-Stewart, Esther, and Justin Parsler. 2008. “The Difficulties of Playing

a Role in World of Warcraft.” In Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World

of Warcraft Reader, ed. Hilde G. Corneliussen and Jill W. Rettberg, 225–46.

Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Magnet, Shoshana. 2007. “Feminist Sexualities, Race, and the Internet: An

Investigation of suicidegirls.com.” New Media and Society 9(4):577–602.

Merrick, Helen. 1998. “Slumming with the Space Cadets: An Argument for

Feminist Science Fiction.” Outskirts 3. http://www.outskirts.arts.uwa.edu.

au/volumes/volume-3/merrick#top.

———. 2009. The Secret Feminist Cabal. Seattle: Aqueduct Press.

Midgley, Mary. 2004. The Myths We Live By. New York: Routledge Books.

Mohan, Steven, Lars Blumenstein, Rob Boyle, Brian Cross, Nathaniel Dean,

Jack Graham, David Hill, Justin Kugler. 2011. Panopticon. Vol. 1: Habitats,

Surveillance, Uplifts. sthuman Studios.

Nakamura, Lisa. 1995. “Race in/for Cyberspace: Identity Tourism and Racial

Passing on the Internet.” http://www.humanities.uci.edu/mposter/syllabi/

readings/nakamura.html.

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 87 9/24/12 12:57 PM

88 Katherine Angel Cross

———. 2000. Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity and Identity on the Internet. London:

Routledge.

Nardi, Bonnie. 2010. My Life as a Night Elf Priest: An Anthropological Account of

World of Warcraft. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

O’Brien, Jodi. 1999. “Writing in the Body: Gender (Re)Production in Online

Interaction.” In Communities in Cyberspace, ed. Marc Smith and Peter

Kollock, 76–104. London: Routledge.

Pelletier, Caroline. 2008. “Gaming in Context: How Young People Construct

Their Gendered Identities in Playing and Making Games.” In Beyond Barbie

and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming, ed. Yasmin

Kafai, Carrie Heeter, Jill Denner, and Jennifer Sun, 145–160. Cambridge,

MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Posthuman Studios. 2012. Eclipse Phase. http://eclipsephase.com/.

Rose, Hilary. 1994. Love, Power, and Knowledge: Towards a Feminist

Transformation of the Sciences. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Snead, John, Lars Blumenstein, Rob Boyle, Brian Cross, Jack Graham 2009.

Eclipse Phase: The Roleplaying Game of Transhuman Conspiracy and Horror.

Posthuman Studios.

Stone, Allucquére. 1995. The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the

Mechanical Age. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Press.

Stryker, Susan. 2006a. “(De)Subjugated Knowledges: An Introduction to

Transgender Studies.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker

and Stephen Whittle, 1–17. New York: Routledge.

———. 2006b. “My Letter to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of

Chamounix.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker and

Stephen Whittle, 244–56. New York: Routledge.

Sun, Jennifer, Yasmin Kafai, Carrie Heeter, and Jill Denner 2008. Beyond Barbie

and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming. Cambridge:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Taylor, T. L. 2006. Play Between Worlds: Exploring Online Game Culture.

Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Thorne, Barrie. 1993. Gender Play: Girls and Boys in School. New Brunswick:

Rutgers University Press.

Turkle, Shelly. 1995. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. London:

Phoenix.

Young, Filamena. 2012. Flatpack: Fix the Future. Anaheim, CA: Machine Age

Productions.

WSQ_Enchantment_v2.indd 88 9/24/12 12:57 PM

You might also like

- Futurama For Cortex: PremiseDocument5 pagesFuturama For Cortex: PremiseKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- The Defamation of Role-Playing Games and PDFDocument13 pagesThe Defamation of Role-Playing Games and PDFKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- MJCC Employment Application NewDocument4 pagesMJCC Employment Application NewKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Martin Epic GloryDocument23 pagesMartin Epic GloryKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Flat BowDocument4 pagesFlat BowElSombreroNegroNo ratings yet

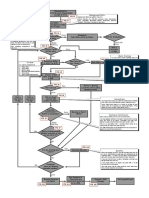

- Cyberpunk 2020 Combat Cheat SheetDocument3 pagesCyberpunk 2020 Combat Cheat SheetKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Zebulon's Guide Quick ReferenceDocument14 pagesZebulon's Guide Quick ReferenceArt Nickles100% (1)

- Collins MMORPG Personality TraitsDocument6 pagesCollins MMORPG Personality TraitsKaiserhuff100% (1)

- Wright Et Al Imaginative Role PlayingDocument31 pagesWright Et Al Imaginative Role PlayingKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Walden Diary of A Murderhobo PDFDocument11 pagesWalden Diary of A Murderhobo PDFKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Burris No Other God Before Mario PDFDocument10 pagesBurris No Other God Before Mario PDFKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Wilson An Exploratory Study PDFDocument60 pagesWilson An Exploratory Study PDFKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Wright Et Al Imaginative Role PlayingDocument31 pagesWright Et Al Imaginative Role PlayingKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Copier Connecting WorldsDocument13 pagesCopier Connecting WorldsKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- La Roche and Blakey 1997 HA PDFDocument24 pagesLa Roche and Blakey 1997 HA PDFKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Hexagonal 19x24Document1 pageHexagonal 19x24KaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Flat BowDocument4 pagesFlat BowElSombreroNegroNo ratings yet

- Character Generation FlowchartDocument1 pageCharacter Generation FlowchartReaderProNo ratings yet

- HolyLandsLE PDFDocument76 pagesHolyLandsLE PDFKaiserhuffNo ratings yet

- Manual of Bayonet ExerciseDocument67 pagesManual of Bayonet ExerciseummonkNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Rbap HHD 2014 Blia Nepal Country ReportDocument82 pagesRbap HHD 2014 Blia Nepal Country ReportSwati AnandNo ratings yet

- "Gender Uncertainty" Invades Public Schools As The Next Wave of The Pansexual Indoctrination of SocietyDocument136 pages"Gender Uncertainty" Invades Public Schools As The Next Wave of The Pansexual Indoctrination of SocietyJudith Reisman, Ph.D.100% (5)

- Transgenderism, Pharmakeia and SorceryDocument9 pagesTransgenderism, Pharmakeia and SorceryJeremy James67% (6)

- Social Justice ReflectionDocument2 pagesSocial Justice Reflectionapi-308033434No ratings yet

- Family Acceptance Project - Helping Families Support Their Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender ChildrenDocument12 pagesFamily Acceptance Project - Helping Families Support Their Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender ChildrenGender SpectrumNo ratings yet

- 0.1 PHD Thesis Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Issues in The Present Legal Scenario Human Rights Perspective PDFDocument168 pages0.1 PHD Thesis Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Issues in The Present Legal Scenario Human Rights Perspective PDFtotallylegalNo ratings yet

- Transgender Status in IndiaDocument8 pagesTransgender Status in IndiaVishwaPratapNo ratings yet

- Current Issues in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) HealthDocument12 pagesCurrent Issues in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) HealthapolloNo ratings yet

- Assignment in World CultureDocument3 pagesAssignment in World CultureCristina RamirezNo ratings yet

- Canete SOGIE Bill Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesCanete SOGIE Bill Reaction PaperDave Vasquez100% (2)

- Pflag Pflag Pflag Pflag: Progress Toward Ending Bullying in Our SchoolsDocument6 pagesPflag Pflag Pflag Pflag: Progress Toward Ending Bullying in Our SchoolsDavid HorowitzNo ratings yet

- The Restroom Revolution: Unisex Toilets and Campus PoliticsDocument19 pagesThe Restroom Revolution: Unisex Toilets and Campus PoliticsNYU PressNo ratings yet

- A State-by-State Examination of Nondiscrimination Laws and PoliciesDocument84 pagesA State-by-State Examination of Nondiscrimination Laws and PoliciesCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- Volume 46, Issue 22, May 29, 2015Document40 pagesVolume 46, Issue 22, May 29, 2015BladeNo ratings yet

- Being Transgender and Transgender Being - Sophie Grace-ChappellDocument10 pagesBeing Transgender and Transgender Being - Sophie Grace-ChappellPhantom Power100% (3)

- Chapter 1 3 Jills PDFDocument16 pagesChapter 1 3 Jills PDFJan Wilfred EbaleNo ratings yet

- Updated GROUP 4 Thesis ABM 3 Mar. 15, 19Document27 pagesUpdated GROUP 4 Thesis ABM 3 Mar. 15, 19Caryl Mae PullarosteNo ratings yet

- FileStamped - Complaint MainDocument96 pagesFileStamped - Complaint MainA.W. CarrosNo ratings yet

- Section 377 and Beyond: A New Era For Transgender Equality?Document12 pagesSection 377 and Beyond: A New Era For Transgender Equality?Suvodip EtcNo ratings yet

- Andrew Culp - Dark DeleuzeDocument193 pagesAndrew Culp - Dark DeleuzeNicolas FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Sex ModifyDocument41 pagesSex Modifyshyam rana100% (1)

- The Sexual SelfDocument83 pagesThe Sexual Self-------No ratings yet

- Disha Master Vocabulary in 50 Days Book DownloadDocument269 pagesDisha Master Vocabulary in 50 Days Book DownloadanshuNo ratings yet

- Issues and Management of Transgender Community in Pakistan A Case Study of LahoreDocument11 pagesIssues and Management of Transgender Community in Pakistan A Case Study of Lahoreanhum jadoonNo ratings yet

- Psychological Practice Girls Women PDFDocument38 pagesPsychological Practice Girls Women PDFBhargav100% (1)

- Dictionary of LGBT TermsDocument2 pagesDictionary of LGBT Terms00041xyzNo ratings yet

- NALSA Vs UOI PresentationDocument6 pagesNALSA Vs UOI PresentationPrerika100% (1)

- Love Sex RelationshipsDocument9 pagesLove Sex RelationshipsDaniel HorgaNo ratings yet

- X. Responding To Transgender Victims of Sexual Assault.2014.Document140 pagesX. Responding To Transgender Victims of Sexual Assault.2014.Sarah DeNo ratings yet

- GED109 - A51-Community Profiling-Roxas, Juan Carlos B.Document16 pagesGED109 - A51-Community Profiling-Roxas, Juan Carlos B.Juan Carlos RoxasNo ratings yet