Professional Documents

Culture Documents

100%) Does Not Immediately Result in The DNA Test Result Being Admitted As An Overwhelming

Uploaded by

Ace MereriaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

100%) Does Not Immediately Result in The DNA Test Result Being Admitted As An Overwhelming

Uploaded by

Ace MereriaCopyright:

Available Formats

NERISSA PAZ HERRERA

ROSENDO HERRERA, petitioner,

vs.

ROSENDO ALBA, minor, represented by his mother ARMI A. ALBA, and HON.

NIMFA CUESTA-VILCHES, Presiding Judge, Branch 48, Regional Trial Court,

Manila, respondents.

G.R. No. 148220 June 15, 2005

FACTS:

On 14 May 1998, then thirteen-year-old Rosendo Alba ("respondent"), represented by his mother

Armi Alba, filed before the trial court a petition for compulsory recognition, support and damages

against petitioner. On 7 August 1998, petitioner filed his answer with counterclaim where he

denied that he is the biological father of respondent. Petitioner also denied physical contact with

respondent’s mother.

Respondent filed a motion to direct the taking of DNA paternity testing to abbreviate the

proceedings. To support the motion, respondent presented the testimony of Saturnina C. Halos,

Ph.D. When she testified, Dr. Halos was an Associate Professor at De La Salle University where

she taught Cell Biology. She was also head of the University of the Philippines Natural Sciences

Research Institute ("UP-NSRI"), a DNA analysis laboratory. She was a former professor at the

University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City, where she developed the Molecular

Biology Program and taught Molecular Biology. In her testimony, Dr. Halos described the

process for DNA paternity testing and asserted that the test had an accuracy rate of 99.9999% in

establishing paternity.

Petitioner opposed DNA paternity testing and contended that it has not gained acceptability.

Petitioner further argued that DNA paternity testing violates his right against self-incrimination.

ISSUE: Whether or not the DNA is acceptable as evidence in determining filiation? Does this

testing violates his right against self-incrimination?

HELD:

YES. In the Vallejo Case, the Supreme Court recognized DNA analysis as admissible evidence.

It is true that in 1997, the Supreme Court ruled in Pe Lim vs CA that DNA testing is not yet

recognized in the Philippines and at the time when he questioned the order of the trial court, the

prevailing doctrine was the Pe Lim case; however, in 2002 there is already no question as to the

acceptability of DNA test results as admissible object evidence in Philippine courts. This was the

decisive ruling in the case of People vs Vallejo (2002).

n this case, the Supreme Court declared that in filiation cases, before paternity inclusion can be

had, the DNA test result must state that the there is at least a 99.9% probability that the person is

the biological father. However, a 99.9% probability of paternity (or higher but never possibly a

100% ) does not immediately result in the DNA test result being admitted as an overwhelming

evidence. It does not automatically become a conclusive proof that the alleged father, in this case

Herrera, is the biological father of the child (Alba). Such result is still a disputable or a refutable

evidence which can be brought down if the Vallejo Guidelines are not complied with.

In the issue of self-incrimination, submitting to DNA testing is not violative of the right against

self-incrimination. The right against self-incrimination is just a prohibition on the use of physical

or moral compulsion to extort communication (testimonial evidence) from a defendant, not an

exclusion of evidence taken from his body when it may be material. There is no “testimonial

compulsion” in the getting of DNA sample from Herrera, hence, he cannot properly invoke self-

incrimination.

You might also like

- 150+ Services You Can Offer As A VADocument8 pages150+ Services You Can Offer As A VAAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- de La Salle University, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 127980 Case DigestDocument3 pagesde La Salle University, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 127980 Case DigestJanet Fabi100% (1)

- Herrera Vs AlbaDocument2 pagesHerrera Vs AlbaKristine Mae JaposNo ratings yet

- Torts Long Summary SPring 1LDocument141 pagesTorts Long Summary SPring 1Lvarshnis250% (2)

- Invoice: Item Description Unit Price Quantity AmountDocument1 pageInvoice: Item Description Unit Price Quantity AmountAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Annex H, Judicial AffidavitDocument7 pagesAnnex H, Judicial AffidavitAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument4 pagesPDFAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- People V TomioDocument4 pagesPeople V TomioLilu BalgosNo ratings yet

- Ebill 12 19 2018Document1 pageEbill 12 19 2018Ace MereriaNo ratings yet

- Manila Diamond Hotel Ee Union Vs CA GR 140518Document2 pagesManila Diamond Hotel Ee Union Vs CA GR 140518LIERANo ratings yet

- Edgardo A. Gaanan, vs. Intermediate Appellate Court and People of The Philippines SCRA 112 (1986) G.R. No. L-69809 October 16, 1986 FactsDocument2 pagesEdgardo A. Gaanan, vs. Intermediate Appellate Court and People of The Philippines SCRA 112 (1986) G.R. No. L-69809 October 16, 1986 FactsAlyssa Mae Ogao-ogaoNo ratings yet

- Torts 4Document2 pagesTorts 4Bing MiloNo ratings yet

- Villanueva JR V CADocument1 pageVillanueva JR V CAAnonymous yRXE6QNo ratings yet

- V. Chairman, Philippine Veterans Administration: The Right of ActionDocument1 pageV. Chairman, Philippine Veterans Administration: The Right of ActionAira Marie M. AndalNo ratings yet

- Syllabus 2013 - AUFDocument13 pagesSyllabus 2013 - AUFDanny DayanNo ratings yet

- Lechugas v. CA Case DigestDocument2 pagesLechugas v. CA Case DigestKuh Ne100% (1)

- Evidence Quiz1 1st Day Students'Document6 pagesEvidence Quiz1 1st Day Students'Aice ManalotoNo ratings yet

- 250 Pentagon Steel V, CADocument2 pages250 Pentagon Steel V, CANinaNo ratings yet

- Equatorial Realty DevelopmentDocument4 pagesEquatorial Realty DevelopmentellaNo ratings yet

- Marcelo vs. BungubungDocument18 pagesMarcelo vs. BungubungLourdes LescanoNo ratings yet

- People vs. EspinozaDocument1 pagePeople vs. EspinozaLe AnnNo ratings yet

- Francisco vs. NLRC: G.R. No. 170087Document1 pageFrancisco vs. NLRC: G.R. No. 170087scartoneros_1No ratings yet

- West Coast Life Insurance v. Geo. N. HurdDocument2 pagesWest Coast Life Insurance v. Geo. N. Hurdrhod leysonNo ratings yet

- Golden Farms v. Sec. of Labor (G.R. No. 102130. July 26, 1994.)Document1 pageGolden Farms v. Sec. of Labor (G.R. No. 102130. July 26, 1994.)Emmanuel Alejandro YrreverreIiiNo ratings yet

- People v. Calma (Opinion)Document3 pagesPeople v. Calma (Opinion)Peter Joshua OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Property Case DigestDocument23 pagesProperty Case DigestsalpanditaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 ReportDocument16 pagesChapter 4 ReportShielaMarie MalanoNo ratings yet

- Alliance of Non-Life Insurance Workers v. MendozaDocument73 pagesAlliance of Non-Life Insurance Workers v. MendozaNestor LimNo ratings yet

- People V GloriaDocument2 pagesPeople V GloriaBananaNo ratings yet

- Acar Vs RosalDocument2 pagesAcar Vs RosalJean HerreraNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Derla Vs Heirs of HipolitoDocument28 pagesHeirs of Derla Vs Heirs of HipolitoPing KyNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Cases Part 1-Judge Dela RosaDocument9 pagesCriminal Procedure Cases Part 1-Judge Dela RosaRegina Elim Perocillo Ballesteros-ArbisonNo ratings yet

- Adminpub ReviewerDocument68 pagesAdminpub ReviewerJm CruzNo ratings yet

- Digest PP vs. PATEÑODocument1 pageDigest PP vs. PATEÑOStef OcsalevNo ratings yet

- Israel G. Peralta vs. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesIsrael G. Peralta vs. Court of AppealsArianne AstilleroNo ratings yet

- Heirs of LumucsoDocument2 pagesHeirs of LumucsoaudreyracelaNo ratings yet

- Soliven Vs Fastforms Phils Inc.Document2 pagesSoliven Vs Fastforms Phils Inc.Michael Joseph NogoyNo ratings yet

- People V Rivera (Sanchez)Document7 pagesPeople V Rivera (Sanchez)Peter Joshua OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document6 pagesChapter 7Matata PhilipNo ratings yet

- Case 13 - UNILEVER vs. RiveraDocument3 pagesCase 13 - UNILEVER vs. RiveraJemuel LadabanNo ratings yet

- General PrinciplesDocument10 pagesGeneral PrinciplesEKANGNo ratings yet

- 8: Limitations/ Restrictions of Government Lawyers in The Practice of LAWDocument53 pages8: Limitations/ Restrictions of Government Lawyers in The Practice of LAWMilea Kim Karla CabuhatNo ratings yet

- Mayor Maximum To Prision Correccional Medium AsDocument15 pagesMayor Maximum To Prision Correccional Medium AsAyban NabatarNo ratings yet

- AdminLaw 2Document4 pagesAdminLaw 2Ronna Faith MonzonNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Legal FormsDocument49 pagesCase Digest - Legal FormsShella VamNo ratings yet

- Evidence - Set D: G.R. No. 165748 September 14, 2011Document5 pagesEvidence - Set D: G.R. No. 165748 September 14, 2011Christianne Joyse MerreraNo ratings yet

- Perez v. EstradaDocument2 pagesPerez v. EstradaRose De JesusNo ratings yet

- Rivera Vs CSCDocument3 pagesRivera Vs CSCWilfredNo ratings yet

- People V LungayanDocument1 pagePeople V LungayanGSSNo ratings yet

- Crimpro Syllabus CasesDocument178 pagesCrimpro Syllabus CasesKC BarrasNo ratings yet

- Atty Palad Vs Solis DigestDocument2 pagesAtty Palad Vs Solis DigestRaiza Joy Sarte100% (2)

- 29 - Lechugas v. CADocument2 pages29 - Lechugas v. CARan MendozaNo ratings yet

- Scripts To Overcome The Toughest Buyer Objections and Close More SalesDocument5 pagesScripts To Overcome The Toughest Buyer Objections and Close More SalesAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- 6 People V Chua - DigestDocument1 page6 People V Chua - DigestLogia LegisNo ratings yet

- People V VersozaDocument2 pagesPeople V VersozaFriktNo ratings yet

- US v. Barias Case BriefDocument1 pageUS v. Barias Case BriefJustin Val VirtudazoNo ratings yet

- 31 Matias V GonzalesDocument1 page31 Matias V GonzalesannlorenzoNo ratings yet

- Summary - Rosendo Herrera Vs Rosendo AlbaDocument4 pagesSummary - Rosendo Herrera Vs Rosendo AlbaMariel D. PortilloNo ratings yet

- UP Law F2021: Herrera V Alba 2005 CarpioDocument5 pagesUP Law F2021: Herrera V Alba 2005 CarpioUP lawNo ratings yet

- Pelizloy Realty CorporationDocument2 pagesPelizloy Realty CorporationMary AnneNo ratings yet

- Ong-Chia-v-Republic-DigestDocument1 pageOng-Chia-v-Republic-DigestZimply Donna LeguipNo ratings yet

- Practice of LawDocument13 pagesPractice of LawJason LacernaNo ratings yet

- Soliven v. FastformsDocument3 pagesSoliven v. FastformsTippy Dos SantosNo ratings yet

- NATRES ARIGO Vs SWIFTDocument11 pagesNATRES ARIGO Vs SWIFTSu Kings AbetoNo ratings yet

- Applicant 1508 PDFDocument26 pagesApplicant 1508 PDFPalomita SharmaNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Recit (Week 2)Document25 pagesLegal Ethics Recit (Week 2)Michael Renz PalabayNo ratings yet

- Cathay Pacific v. Sps VasquezDocument4 pagesCathay Pacific v. Sps VasquezJulian100% (1)

- Compilation ObliconDocument7 pagesCompilation Obliconkim_santos_20No ratings yet

- 4 Equatorial Realty Development, Inc. vs. Mayfair Theater, Inc.Document2 pages4 Equatorial Realty Development, Inc. vs. Mayfair Theater, Inc.JemNo ratings yet

- Torts & Damages Prof. Casis: Naguiat V NLRC (National Organization of Workingmen and Galang)Document26 pagesTorts & Damages Prof. Casis: Naguiat V NLRC (National Organization of Workingmen and Galang)Carlo TibayanNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 194024Document17 pagesG.R. No. 194024Johari Valiao AliNo ratings yet

- Monroy Vs CA 20 SCRA 620Document2 pagesMonroy Vs CA 20 SCRA 620ANA ANNo ratings yet

- Enrile v. Salazar, 186 SCRA 217Document6 pagesEnrile v. Salazar, 186 SCRA 217PRINCESS MAGPATOCNo ratings yet

- Herrera V AlbaDocument1 pageHerrera V AlbaClark Vincent PonlaNo ratings yet

- Z2Tfp: Phial Very#+Ellneriwir %:I::A::Raldtry#,,Ndin:::::##: #:C #Document3 pagesZ2Tfp: Phial Very#+Ellneriwir %:I::A::Raldtry#,,Ndin:::::##: #:C #Ace MereriaNo ratings yet

- InjunctionDocument7 pagesInjunctionAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Juris CompilationDocument3 pagesJuris CompilationAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Lyrics For ChoirDocument3 pagesLyrics For ChoirAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Scribblings, Niebres Vs Heirs of Arroyo 0036.10.001Document2 pagesScribblings, Niebres Vs Heirs of Arroyo 0036.10.001Ace MereriaNo ratings yet

- Additional For InjunctionDocument1 pageAdditional For InjunctionAce MereriaNo ratings yet

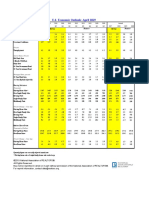

- Forecast 04 2019 Us Ecoanomic Outlook 03-28-2019Document1 pageForecast 04 2019 Us Ecoanomic Outlook 03-28-2019Ace MereriaNo ratings yet

- Thank You For Your Payment!: Return To Home PrintDocument1 pageThank You For Your Payment!: Return To Home PrintAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- 2Document20 pages2Ace MereriaNo ratings yet

- Itinerary Lala HeheDocument1 pageItinerary Lala HeheAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Sunday AssignmentDocument2 pagesSunday AssignmentAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Quote: Southwest Electrical Contracting Services, LTDDocument1 pageQuote: Southwest Electrical Contracting Services, LTDAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Invoice 189419 From Action Appliance ServiceDocument1 pageInvoice 189419 From Action Appliance ServiceAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Coastwise Vs CA, GR114167Document3 pagesCoastwise Vs CA, GR114167Ace MereriaNo ratings yet

- Case 1 To 5 CivProcDocument8 pagesCase 1 To 5 CivProcAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Circle Prospecting From DownunderDocument2 pagesCircle Prospecting From DownunderAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Ideapad320-15isk 320x-15isk 320-15ikb 320x-15ikb 320-15ikbtouch HMM 201704Document84 pagesIdeapad320-15isk 320x-15isk 320-15ikb 320x-15ikb 320-15ikbtouch HMM 201704MarcoNo ratings yet

- Invoice 3860Document1 pageInvoice 3860Ace MereriaNo ratings yet

- Invoice: Item Description Unit Price Quantity AmountDocument1 pageInvoice: Item Description Unit Price Quantity AmountAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Invoice0003240 5b3a5daf70929 PDFDocument1 pageInvoice0003240 5b3a5daf70929 PDFAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Case Study Final (2) BrewCloomDocument1 pageCase Study Final (2) BrewCloomAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Final, Case Study On The Insurance IndustryDocument2 pagesFinal, Case Study On The Insurance IndustryAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Invoice 189305 From Action Appliance ServiceDocument1 pageInvoice 189305 From Action Appliance ServiceAce MereriaNo ratings yet

- Stipulation To Amend Pre-Trial Scheduling OrderDocument5 pagesStipulation To Amend Pre-Trial Scheduling OrderyogaloyNo ratings yet

- 78.a.c. Ransom Labor Union-CCLU vs. NLRCDocument5 pages78.a.c. Ransom Labor Union-CCLU vs. NLRCvince005No ratings yet

- Honor KillingDocument18 pagesHonor KillingMehak Gul BushraNo ratings yet

- Digests 357-361 Involuntary ServitudeDocument7 pagesDigests 357-361 Involuntary ServitudeJaneNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Arresting OfficersDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Arresting Officersprincess agabinNo ratings yet

- Amarnath Choudhary V. Braithwaite and Co. Ltd. - Case AnalysisDocument17 pagesAmarnath Choudhary V. Braithwaite and Co. Ltd. - Case AnalysisSrinjoy Bhattacharya0% (1)

- Asistio vs. PeopleDocument27 pagesAsistio vs. PeopleDianne May CruzNo ratings yet

- Trina Mayes McGee Report 12-17-2013 (2) - RedactedDocument25 pagesTrina Mayes McGee Report 12-17-2013 (2) - Redactedwellind3No ratings yet

- Criminal Defamation Is Unconstitutional - Full JudgmentDocument21 pagesCriminal Defamation Is Unconstitutional - Full JudgmentmajorNo ratings yet

- Dimarucot vs. People G.R. No. 183975, 20 September 2010Document6 pagesDimarucot vs. People G.R. No. 183975, 20 September 2010Jalina PumbayaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Appeal: Drew Peterson (Appellant's Brief) - Filed 6/29/2016Document156 pagesSupreme Court Appeal: Drew Peterson (Appellant's Brief) - Filed 6/29/2016Justice CaféNo ratings yet

- Comment-Dreu CaseDocument4 pagesComment-Dreu CaseRosemarie JanoNo ratings yet

- Bifurcation of Trials in OntarioDocument8 pagesBifurcation of Trials in OntarioppengelleyNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. PACITO Ordoo Y Negranza Alias Asing and Apolonio Medina Y NOSUELO Alias POLING, Accused-AppellantsDocument9 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. PACITO Ordoo Y Negranza Alias Asing and Apolonio Medina Y NOSUELO Alias POLING, Accused-AppellantsFaye Jennifer Pascua PerezNo ratings yet

- Vinuya vs. Romulo 619 Scra 533 (2010)Document3 pagesVinuya vs. Romulo 619 Scra 533 (2010)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- United States of America, Appellee-Cross-Appellant v. Joseph Savarese, AKA "Joe Dinga", Carmine Russo, AKA "Baby Carmine", Elio Albanese, AKA "Chinatown", Nicholas Fiorello, AKA "Larry K. Nick", George Diplacidi, AKA "Georgie", Ramona Reynolds, Craig A. Reynolds, Natalie Delutro, Anthony Capanelli, AKA "Little Anthony", Defendant-Appellant-Cross-Appellee, 404 F.3d 651, 2d Cir. (2005)Document7 pagesUnited States of America, Appellee-Cross-Appellant v. Joseph Savarese, AKA "Joe Dinga", Carmine Russo, AKA "Baby Carmine", Elio Albanese, AKA "Chinatown", Nicholas Fiorello, AKA "Larry K. Nick", George Diplacidi, AKA "Georgie", Ramona Reynolds, Craig A. Reynolds, Natalie Delutro, Anthony Capanelli, AKA "Little Anthony", Defendant-Appellant-Cross-Appellee, 404 F.3d 651, 2d Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Warren Vs StateDocument7 pagesWarren Vs StateRelmie TaasanNo ratings yet

- (G.R. NO. 179061: July 13, 2009) Sheala P. Matrido, Petitioner, V. People of The PhilippinesDocument1 page(G.R. NO. 179061: July 13, 2009) Sheala P. Matrido, Petitioner, V. People of The PhilippinesKlydeen AgitoNo ratings yet

- Ilbur D. Thompson v. Butch Hamilton Ronnie Law, 127 F.3d 1109, 10th Cir. (1997)Document3 pagesIlbur D. Thompson v. Butch Hamilton Ronnie Law, 127 F.3d 1109, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dilemma of Police Order 2002Document3 pagesDilemma of Police Order 2002humamaNo ratings yet

- 57 Digest Hadjula V Atty. MadiandaDocument1 page57 Digest Hadjula V Atty. MadiandaSharon G. BalingitNo ratings yet

- ...Document3 pages...Yassin MalayNo ratings yet