Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Grounds When Rule 65 Is Applicable To Summary Proceedings

Uploaded by

Harold Estacio0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

99 views5 pagesrwqerewqf

Original Title

Grounds When Rule 65 is Applicable to Summary Proceedings

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentrwqerewqf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

99 views5 pagesGrounds When Rule 65 Is Applicable To Summary Proceedings

Uploaded by

Harold Estaciorwqerewqf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

SUMMARY PROCEDURE: EXCEPTIONAL CASES

WHERE CERTIORARI WAS ALLOWED BY SC: GR NO.

194880

Proceeding now to determine that very question of law, the Court

finds that it was erroneous for the RTC to have taken cognizance of

the Rule 65 Petition of respondent Sunvar, since the Rules on

Summary Procedure expressly prohibit this relief for unfavorable

interlocutory orders of the MeTC. Consequently, the assailed RTC

Decision is annulled.

Under the Rules on Summary Procedure, a certiorari petition under

Rule 65 against an interlocutory order issued by the court in a

summary proceeding is a prohibited pleading.[52] The prohibition

is plain enough, and its further exposition is unnecessary verbiage.

[53] The RTC should have dismissed outright respondent Sunvar’s

Rule 65 Petition, considering that it is a prohibited pleading.

Petitioners have already alerted the RTC of this legal bar and

immediately prayed for the dismissal of thecertiorari Petition.

[54] Yet, the RTC not only refused to dismiss

the certiorari Petition,[55] but even proceeded to hear the Rule 65

Petition on the merits.

Respondent Sunvar’s reliance on Bayog v. Natino[56] and Go v.

Court of Appeals[57] to justify acertiorari review by the RTC

owing to “extraordinary circumstances” is misplaced. In both

cases, there were peculiar and specific circumstances that justified

the filing of the mentioned prohibited pleadings under the Revised

Rules on Summary Procedure – conditions that are not availing in

the case of respondent Sunvar.

In Bayog, Alejandro Bayog filed with the Municipal Circuit Trial

Court (MCTC) of Patnongon-Bugasong-Valderama, Antique an

ejectment case against Alberto Magdato, an agricultural tenant-

lessee who had built a house over his property. When Magdato, an

illiterate farmer, received the Summons from the MCTC to file his

answer within 10 days, he was stricken with pulmonary

tuberculosis and was able to consult a lawyer in San Jose, Antique

only after the reglementary period. Hence, when the Answer of

Magdato was filed three days after the lapse of the 10-day period,

the MCTC ruled that it could no longer take cognizance of his

Answer and, hence, ordered his ejectment from Bayog’s land.

When his house was demolished in January 1994, Magdato filed a

Petition for Relief with the RTC-San Jose, Antique, claiming that

he was a duly instituted tenant in the agricultural property, and that

he was deprived of due process. Bayog, the landowner, moved to

dismiss the Petition on the ground of lack of jurisdiction on the

part of the RTC, since a petition for relief from judgment covering

a summary proceeding was a prohibited pleading. The RTC,

however, denied his Motion to Dismiss and remanded the case to

the MCTC for proper disposal.

In resolving the Rule 65 Petition, we ruled that although a petition

for relief from judgment was a prohibited pleading under the

Revised Rules on Summary Procedure, the Court nevertheless

allowed the filing of the Petition pro hac vice, since Magdato

would otherwise suffer grave injustice and irreparable injury:

We disagree with the RTC’s holding that a petition for relief from

judgment (Civil Case No. 2708) is not prohibited under the

Revised Rule on Summary Procedure, in light of

the Jakihaca ruling. When Section 19 of the Revised Rule on

Summary Procedure bars a petition for relief from judgment, or a

petition forcertiorari, mandamus, or prohibition against any

interlocutory order issued by the court, it has in mind no other than

Section 1, Rule 38 regarding petitions for relief from judgment,

and Rule 65 regarding petitions for certiorari, mandamus, or

prohibition, of the Rules of Court, respectively. These petitions are

cognizable by Regional Trial Courts, and not by Metropolitan Trial

Courts, Municipal Trial Courts, or Municipal Circuit Trial Courts.

If Section 19 of the Revised Rule on Summary Procedure and

Rules 38 and 65 of the Rules of Court are juxtaposed, the

conclusion is inevitable that no petition for relief from judgment

nor a special civil action of certiorari, prohibition,

or mandamus arising from cases covered by the Revised Rule on

Summary Procedure may be filed with a superior court. This is but

consistent with the mandate of Section 36 of B.P. Blg. 129 to

achieve an expeditious and inexpensive determination of the cases

subject of summary procedure.

Nevertheless, in view of the unusual and peculiar circumstances of

this case, unless some form of relief is made available to

MAGDATO, the grave injustice and irreparable injury that visited

him through no fault or negligence on his part will only be

perpetuated. Thus, the petition for relief from judgment which he

filed may be allowed or treated, pro hac vice, either as an

exception to the rule, or a regular appeal to the RTC, or even an

action to annul the order (decision) of the MCTC of 20 September

1993. As an exception, the RTC correctly held that the

circumstances alleged therein and the justification pleaded worked

in favor of MAGDATO, and that the motion to dismiss Civil Case

No. 2708 was without merit. xxx [58] (Emphasis supplied.)

On the other hand, in Go v. Court of Appeals, the Court was

confronted with a procedural void in the Revised Rules of

Summary Procedure that justified the resort to a Rule 65 Petition in

the RTC. In that case, the preliminary conference in the subject

ejectment suit was held in abeyance by the Municipal Trial Court

in Cities (MTCC) of Iloilo City until after the case for specific

performance involving the same parties shall have been finally

decided by the RTC. The affected party appealed the suspension

order to the RTC. In response, the adverse party moved to dismiss

the appeal on the ground that it concerned an interlocutory order in

a summary proceeding that was not the subject of an appeal. The

RTC denied the Motion to Dismiss and subsequently directed the

MTCC to proceed with the hearing of the ejectment suit, a ruling

that was upheld by the appellate court.

In affirming the Decisions of the RTC and CA, the Supreme Court

allowed the filing of a petition for certiorari against an

interlocutory order in an ejectment suit, considering that the

affected party was deprived of any recourse to the MTCC’s

erroneous suspension of a summary proceeding. Retired Chief

Justice Artemio V. Panganiban eloquently explained the procedural

void in this wise:

Indisputably, the appealed [suspension] order is interlocutory, for

“it does not dispose of the case but leaves something else to be

done by the trial court on the merits of the case.” It is axiomatic

that an interlocutory order cannot be challenged by an appeal.

Thus, it has been held that “the proper remedy in such cases is an

ordinary appeal from an adverse judgment on the

merits incorporating in said appeal the grounds for assailing the

interlocutory order. Allowing appeals from interlocutory orders

would result in the ‘sorry spectacle’ of a case being subject of a

counterproductive ping-pong to and from the appellate court as

often as a trial court is perceived to have made an error in any of

its interlocutory rulings. However, where the assailed interlocutory

order is patently erroneous and the remedy of appeal would not

afford adequate and expeditious relief, the Court may

allow certiorari as a mode of redress.”

Clearly, private respondent cannot appeal the order, being

interlocutory. But neither can it file a petition for certiorari,

because ejectment suits fall under the Revised Rules on Summary

Procedure, Section 19(g) of which considers petitions

for certiorari prohibited pleadings:

xxx xxx xxx

Based on the foregoing, private respondent was literally caught

“between Scylla and Charybdis” in the procedural void observed

by the Court of Appeals and the RTC. Under these extraordinary

circumstances, the Court is constrained to provide it with a remedy

consistent with the objective of speedy resolution of cases.

As correctly held by Respondent Court of Appeals, “the purpose of

the Rules on Summary Procedure is ‘to achieve an expeditious and

inexpensive determination of cases without regard to technical

rules.’ (Section 36, Chapter III, BP Blg. 129)” Pursuant to this

objective, the Rules prohibit petitions for certiorari, like a number

of other pleadings, in order to prevent unnecessary delays and to

expedite the disposition of cases. In this case, however, private

respondent challenged the MTCC order delaying the ejectment

suit, precisely to avoid the mischief envisioned by the Rules.

Thus, this Court holds that in situations wherein a summary

proceeding is suspended indefinitely, a petition

for certiorari alleging grave abuse of discretion may be allowed.

Because of the extraordinary circumstances in this case, a petition

for certiorari, in fact, gives spirit and life to the Rules on Summary

Procedure. A contrary ruling would unduly delay the disposition of

the case and negate the rationale of the said Rules.[59] (Emphasis

supplied.)

Contrary to the assertion of respondent Sunvar, the factual

circumstances in these two cases are not comparable with

respondents’ situation, and our rulings therein are inapplicable to

its cause of action in the present suit. As this Court explained

in Bayog, the general rule is that no special civil action for

certiorari may be filed with a superior court from cases covered by

the Revised Rules on Summary Procedure. Respondent Sunvar

filed a certiorari Petition in an ejectment suit pending before the

MeTC. Worse, the subject matter of the Petition was the denial of

respondent’s Motion to Dismiss, which was necessarily an

interlocutory order, which is generally not the subject of an appeal.

No circumstances similar to the situation of the agricultural tenant-

lessee in Bayog are present to support the relaxation of the general

rule in the instant case. Respondent cannot claim to have been

deprived of reasonable opportunities to argue its case before a

summary judicial proceeding.

Moreover, there exists no procedural void akin to that in Go v.

Court of Appeals that would justify respondent’s resort to a

certiorari Petition before the RTC. When confronted with the

MeTC’s adverse denial of its Motion to Dismiss in the ejectment

case, the expeditious and proper remedy for respondent should

have been to proceed with the summary hearings and to file its

answer. Indeed, its resort to acertiorari Petition in the RTC over an

interlocutory order in a summary ejectment proceeding was not

only prohibited. The certiorari Petition was already a superfluity on

account of respondent’s having already taken advantage of a

speedy and available remedy by filing an Answer with the MeTC.

Respondent Sunvar failed to substantiate its claim of extraordinary

circumstances that would constrain this Court to apply the

exceptions obtaining in Bayog and Go. The Court hesitates to

liberally dispense the benefits of these two judicial precedents to

litigants in summary proceedings, lest these exceptions be

regularly abused and freely availed of to defeat the very goal of an

expeditious and inexpensive determination of an unlawful detainer

suit. If the Court were to relax the interpretation of the prohibition

against the filing of certiorari petitions under the Revised Rules on

Summary Procedure, the RTCs may be inundated with similar

prayers from adversely affected parties questioning every order of

the lower court and completely dispensing with the goal of

summary proceedings in forcible entry or unlawful detainer suits.

You might also like

- Dacion en Pago 4Document2 pagesDacion en Pago 4Sec PillarsNo ratings yet

- What Acts Constitute Alteration of Co-Owned Property Under Article 491 of the Civil CodeDocument3 pagesWhat Acts Constitute Alteration of Co-Owned Property Under Article 491 of the Civil CodepdasilvaNo ratings yet

- Filipino woman files ejectment case against barangay residentDocument19 pagesFilipino woman files ejectment case against barangay residentFrancis Leo TianeroNo ratings yet

- 46 Petition For Review RTC CADocument18 pages46 Petition For Review RTC CAChristine Joy PrestozaNo ratings yet

- Consent FormDocument1 pageConsent FormMeriam FernandezNo ratings yet

- Written Interrogatories SampleDocument5 pagesWritten Interrogatories SamplevictoriaNo ratings yet

- Dacion en Pago AgreementDocument3 pagesDacion en Pago AgreementHannah Quinones100% (1)

- Print - Siliman Rem QnawDocument122 pagesPrint - Siliman Rem QnawbubblingbrookNo ratings yet

- Presentation of ProsecutionDocument2 pagesPresentation of ProsecutionPia Vanessa CeballosNo ratings yet

- Challenge Judgment Due to Wrong AddressDocument17 pagesChallenge Judgment Due to Wrong Addressgavy cortonNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of BantayanDocument3 pagesAffidavit of BantayanChris.No ratings yet

- Replevin ComplaintDocument2 pagesReplevin ComplaintChrisel Joy Casuga SorianoNo ratings yet

- Tips and Exercises - Teaching Cross-Examination For The Defense - March 2019Document7 pagesTips and Exercises - Teaching Cross-Examination For The Defense - March 2019Carlos ArroboNo ratings yet

- Petition For Cancellation of EntryDocument1 pagePetition For Cancellation of EntryCyrill L. MarkNo ratings yet

- RULE 132 Rules of Court - Presentation of EvidenceDocument26 pagesRULE 132 Rules of Court - Presentation of EvidenceSannie RemotinNo ratings yet

- Regalado Vs GoDocument13 pagesRegalado Vs GopyulovincentNo ratings yet

- Third SupplementalDocument12 pagesThird SupplementalRetsacelet NamNo ratings yet

- Urgent Motion to Reset Court Hearing Due to ConflictsDocument7 pagesUrgent Motion to Reset Court Hearing Due to ConflictshannahleatanosornNo ratings yet

- Court rulings give weight to personal doctor over company physicianDocument4 pagesCourt rulings give weight to personal doctor over company physiciancesarjruyNo ratings yet

- Order of Presentation of Evidence in CourtDocument3 pagesOrder of Presentation of Evidence in CourtKlieds CunananNo ratings yet

- Petition For Writ of Habeas Data: Regional Trial CourtDocument3 pagesPetition For Writ of Habeas Data: Regional Trial CourtChristian RealNo ratings yet

- Impeachment witness recall rulesDocument1 pageImpeachment witness recall rulesMelvin JonesNo ratings yet

- Gamayon NoticeOfAppealDocument2 pagesGamayon NoticeOfAppealreese93No ratings yet

- Mary Chanyapat - Interim Injunction Protection of The Intellectual Property Laws in ThailandDocument7 pagesMary Chanyapat - Interim Injunction Protection of The Intellectual Property Laws in ThailandMaryNo ratings yet

- Wood Technology Corp v. Equitable Bank G.R. 153867Document6 pagesWood Technology Corp v. Equitable Bank G.R. 153867Dino Bernard LapitanNo ratings yet

- Guidelines To Be Observed in The Conduct of Pre-Trial - Legal WikiDocument8 pagesGuidelines To Be Observed in The Conduct of Pre-Trial - Legal Wikimarcialx100% (1)

- Complaint CivilDocument3 pagesComplaint CivilMaria BethNo ratings yet

- Comment OppositionDocument5 pagesComment OppositionVon Ronald D. SupeñaNo ratings yet

- Adjudicative Support Functions of A COCDocument31 pagesAdjudicative Support Functions of A COCNadine Diamante100% (1)

- Negative Pregnant Cases, Galofa Vs Nee and RP Vs SandiganbayanDocument51 pagesNegative Pregnant Cases, Galofa Vs Nee and RP Vs SandiganbayandonyacarlottaNo ratings yet

- 4-Complaint For Sum of MoneyDocument3 pages4-Complaint For Sum of MoneyDNAANo ratings yet

- Notes Rule 4 9Document110 pagesNotes Rule 4 9Winston Mao TorinoNo ratings yet

- National Labor Relations CommissionDocument8 pagesNational Labor Relations CommissionChloe Sy GalitaNo ratings yet

- Proper Reasons For Objecting To A Question Asked To A Witness IncludeDocument2 pagesProper Reasons For Objecting To A Question Asked To A Witness IncludeChristian Dave Tad-awanNo ratings yet

- Legal Profession FinalDocument28 pagesLegal Profession FinalRenz Lyle LaguitaoNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit Rule ExplainedDocument17 pagesJudicial Affidavit Rule ExplainedAlvin Claridades100% (1)

- Accion ReivindicatoriaDocument1 pageAccion ReivindicatoriaVauge Jill LoonteyNo ratings yet

- Corporate By-Laws Ni KulasaDocument11 pagesCorporate By-Laws Ni KulasaFelix Leonard NovicioNo ratings yet

- PD 957 (Cases)Document9 pagesPD 957 (Cases)Katherine OlidanNo ratings yet

- The Wave Condominium - Rules & RegsDocument12 pagesThe Wave Condominium - Rules & RegsTeena Post/LaughtonNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of Courts in Civil Cases: Original Juris v. Appellate JurisDocument155 pagesJurisdiction of Courts in Civil Cases: Original Juris v. Appellate JurisCarmel Grace KiwasNo ratings yet

- Motion For ExtensionDocument3 pagesMotion For ExtensionGilgoric NgohoNo ratings yet

- Sample Pre Trial Brief and ReplyDocument6 pagesSample Pre Trial Brief and ReplyKnotsNautischeMeilenproStundeNo ratings yet

- State Regulation of Hospital Operation PDFDocument14 pagesState Regulation of Hospital Operation PDFFaith Alexis GalanoNo ratings yet

- Role of the Prosecutor in Criminal Justice (39Document15 pagesRole of the Prosecutor in Criminal Justice (39fe rose sindinganNo ratings yet

- Resignation LetterDocument1 pageResignation LetterstillwinmsNo ratings yet

- 33 Law Firm Interview Questions and How To Answer ThemDocument5 pages33 Law Firm Interview Questions and How To Answer ThemS1626100% (1)

- Rule 34 - Judgment On The PleadingsDocument5 pagesRule 34 - Judgment On The PleadingsAnonymous GMUQYq8100% (1)

- By Laws Stock CorporationDocument10 pagesBy Laws Stock Corporationcrazzy foryouNo ratings yet

- Robbery by BandDocument4 pagesRobbery by BandRuchessNo ratings yet

- Appeal and Bond Notice Ejectment CaseDocument1 pageAppeal and Bond Notice Ejectment CaseRonnie GravosoNo ratings yet

- Notice of Appeal to RTCDocument3 pagesNotice of Appeal to RTCakosierikaNo ratings yet

- Pre-Trial Brief (For The Plaintiff)Document2 pagesPre-Trial Brief (For The Plaintiff)Lyndon BenidoNo ratings yet

- (DRAFT) Pre-Trial BriefDocument6 pages(DRAFT) Pre-Trial BriefYuri SisonNo ratings yet

- Legal Forms 131 181Document115 pagesLegal Forms 131 181Huge Propalde EstolanoNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines: ComplaintDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines: ComplaintRamon Miguel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- CIVPRO Wagan Notes Pre Trial To Modes of DiscoveryDocument3 pagesCIVPRO Wagan Notes Pre Trial To Modes of DiscoveryShauna HerreraNo ratings yet

- Report WritingDocument10 pagesReport WritingLiza Ermita AmzarNo ratings yet

- Legal Forms: 1. Petition For Appointment As Notarial PublicDocument13 pagesLegal Forms: 1. Petition For Appointment As Notarial PublicJayson GalaponNo ratings yet

- II. Case 2 - AL Vs MondejarDocument3 pagesII. Case 2 - AL Vs MondejarJoy GeresNo ratings yet

- Eo 459-1997Document4 pagesEo 459-1997joelhermittNo ratings yet

- Meralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithDocument7 pagesMeralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Updated 2016 IRR - 31 March 2021Document356 pagesUpdated 2016 IRR - 31 March 2021richardNo ratings yet

- Salva Vs Valle-SC Relax The Rules On Appeal Beyond TimeDocument6 pagesSalva Vs Valle-SC Relax The Rules On Appeal Beyond TimeHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- PP Vs Venezuela-MalversationDocument9 pagesPP Vs Venezuela-MalversationHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence On Administrative LawDocument194 pagesJurisprudence On Administrative LawpinoyabogadoNo ratings yet

- PO2 Montoya Case-Service of Notice & Prosecuting Arm Must Be The One File The AppealDocument9 pagesPO2 Montoya Case-Service of Notice & Prosecuting Arm Must Be The One File The AppealHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Vs Villarosa-Technical MalversationDocument8 pagesOmbudsman Vs Villarosa-Technical MalversationHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- PP Vs Venezuela-MalversationDocument9 pagesPP Vs Venezuela-MalversationHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- French Vs CA Unlawful Detainer Vs Forcible EntryDocument5 pagesFrench Vs CA Unlawful Detainer Vs Forcible EntryHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- SAUNAR Back WagesDocument12 pagesSAUNAR Back WagesHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Vs Villarosa-Technical MalversationDocument8 pagesOmbudsman Vs Villarosa-Technical MalversationHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- PNP Vs VILLAFUERTE-BAC Secretariat Are Not LiableDocument29 pagesPNP Vs VILLAFUERTE-BAC Secretariat Are Not LiableHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Meralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithDocument7 pagesMeralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Eversley Vs Aquino-Unlawful Detainer Vs Accion PublicianaDocument15 pagesEversley Vs Aquino-Unlawful Detainer Vs Accion PublicianaHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney: PrincipalDocument1 pageSpecial Power of Attorney: PrincipalHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Court Rules Navy Cannot Evict Retirees Without Legal ActionDocument7 pagesCourt Rules Navy Cannot Evict Retirees Without Legal ActionHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Vs Villarosa-Technical MalversationDocument8 pagesOmbudsman Vs Villarosa-Technical MalversationHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney: PrincipalDocument1 pageSpecial Power of Attorney: PrincipalHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Meralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithDocument7 pagesMeralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- French Vs CA Unlawful Detainer Vs Forcible EntryDocument5 pagesFrench Vs CA Unlawful Detainer Vs Forcible EntryHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Quit Claim With Waiver of RightsDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Quit Claim With Waiver of RightsHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Court Rules Navy Cannot Evict Retirees Without Legal ActionDocument7 pagesCourt Rules Navy Cannot Evict Retirees Without Legal ActionHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Eversley Vs Aquino-Unlawful Detainer Vs Accion PublicianaDocument15 pagesEversley Vs Aquino-Unlawful Detainer Vs Accion PublicianaHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Meralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithDocument7 pagesMeralco Vs Magno-Rules of Procedure Must Be Complied WithHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Salva Vs Valle-SC Relax The Rules On Appeal Beyond TimeDocument6 pagesSalva Vs Valle-SC Relax The Rules On Appeal Beyond TimeHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- PP Vs Venezuela-MalversationDocument9 pagesPP Vs Venezuela-MalversationHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Adverse Claim For Deed of Conditional SaleDocument2 pagesAdverse Claim For Deed of Conditional SaleNancy100% (8)

- Deed of Conditional Sale-CacayuranDocument3 pagesDeed of Conditional Sale-CacayuranHarold EstacioNo ratings yet

- Adverse Claim For Deed of Conditional SaleDocument2 pagesAdverse Claim For Deed of Conditional SaleNancy100% (8)

- Checklist For Appointment Provisional To PermanentDocument4 pagesChecklist For Appointment Provisional To PermanentUniversal CollabNo ratings yet

- Astm D6440 - 1 (En)Document2 pagesAstm D6440 - 1 (En)svvasin2013No ratings yet

- 2D07 4644 Motion For Rehearing/ClarificationsDocument10 pages2D07 4644 Motion For Rehearing/ClarificationsTheresa MartinNo ratings yet

- CH 21 Answer To in Class Diiscussion ProblemsDocument20 pagesCH 21 Answer To in Class Diiscussion ProblemsJakeChavezNo ratings yet

- Badges of Dummy StatusDocument3 pagesBadges of Dummy StatusPamela DeniseNo ratings yet

- View Generated DocsDocument1 pageView Generated DocsNita ShahNo ratings yet

- Corales vs. ECCDocument4 pagesCorales vs. ECCMalenNo ratings yet

- Delos Santos Vs CA, GR No. 178947Document2 pagesDelos Santos Vs CA, GR No. 178947Angel67% (3)

- Cheat Sheet StaticsDocument7 pagesCheat Sheet StaticsDiri SendiriNo ratings yet

- BHM 657 Principles of Accounting IDocument182 pagesBHM 657 Principles of Accounting Itaola100% (1)

- Eric Metcalf TestimonyDocument3 pagesEric Metcalf TestimonyMail TribuneNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Malabanan Vs RepublicDocument9 pagesHeirs of Malabanan Vs RepublicAnisah AquilaNo ratings yet

- J50 Feature Sheet May 2020Document2 pagesJ50 Feature Sheet May 2020victor porrasNo ratings yet

- Pro PerDocument47 pagesPro Perxlrider530No ratings yet

- Ralph Simms TestimonyDocument137 pagesRalph Simms TestimonyJohn100% (1)

- Challan Pharmacy Council Punjab Qualified PersonDocument1 pageChallan Pharmacy Council Punjab Qualified PersonSMIPS GRWNo ratings yet

- Padua Vs PeopleDocument1 pagePadua Vs PeopleKlaire EsdenNo ratings yet

- India S People S WarDocument77 pagesIndia S People S WarSidhartha SamtaniNo ratings yet

- Test Bank 8Document13 pagesTest Bank 8Jason Lazaroff67% (3)

- Financial Support To Third PartiesDocument8 pagesFinancial Support To Third PartiesGojart KamberiNo ratings yet

- SelList R206072020Document71 pagesSelList R206072020akshay aragadeNo ratings yet

- On DFSDocument22 pagesOn DFSAditi pandeyNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: 0450/22 Business StudiesDocument4 pagesCambridge IGCSE: 0450/22 Business StudiesJuan GonzalezNo ratings yet

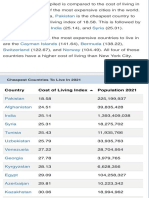

- Cheapest Countries To Live in 2021Document1 pageCheapest Countries To Live in 2021Jindd JaanNo ratings yet

- Padlocks and Fittings GuideDocument4 pagesPadlocks and Fittings GuideVishwakarma VishwakarmaNo ratings yet

- Khách Ngân Hàng 2Document3 pagesKhách Ngân Hàng 2Phan HươngNo ratings yet

- TDS-466 Chembetaine CGFDocument1 pageTDS-466 Chembetaine CGFFabianoNo ratings yet

- Amit Vadhadiya Saving Ac PDFDocument11 pagesAmit Vadhadiya Saving Ac PDFKotadiya ChiragNo ratings yet

- IMUX 2000s Reference Manual 12-12-13Document70 pagesIMUX 2000s Reference Manual 12-12-13Glauco TorresNo ratings yet

- NLRC Affirms Manager's Suspension for Sexual HarassmentDocument3 pagesNLRC Affirms Manager's Suspension for Sexual HarassmentSylina AlcazarNo ratings yet